1. Introduction

In the fields of science and engineering, efficient modeling and solving of complex physical systems have always been a core challenge. Traditional numerical methods, such as the finite element method and the finite difference method, face bottlenecks such as high computational costs and weak model generalization ability when dealing with high-dimensional problems and complex boundary conditions. In recent years, with the rapid development of machine learning, especially the breakthroughs in function approximation and data-driven modeling in deep learning, physics-informed neural network (PINN) [

1] that combines physical prior knowledge with a neural network has emerged, providing a new paradigm for solving the above problems.

Since the PINN framework was proposed, it has made breakthrough progress in fields such as fluid mechanics [

2,

3,

4,

5], solid mechanics [

6,

7,

8], heat conduction [

9,

10], and materials science [

11]. To enhance the performance of the PINN, researchers have proposed a series of advanced optimization methods based on the model and problem characteristics. From the perspective of the PINN model, the main ways to improve the generalization ability and training efficiency of the model are through adjusting the network structure [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], introducing attention mechanism [

17] or adaptive idea [

18], optimizing the construction of loss functions [

19,

20,

21,

22], and making improvements to training strategies [

23,

24,

25]. Starting from the perspective of problem characteristics, domain decomposition techniques are adopted to refine the problem-solving space [

26,

27], and additional constraint conditions are introduced to further optimize the model [

28,

29,

30], thereby achieving a comprehensive improvement in overall performance.

However, despite the enormous potential demonstrated by the PINN, it fails to directly solve fractional partial differential equations (FPDEs) due to the inability of the automatic differentiation technique to calculate integrals. Pang et al. [

31] proposed using the finite difference method, the Grünwald–Letnikov scheme, to approximate fractional derivatives and developed fractional PINNs (fPINNs). Ma et al. [

32] used the L1 formula and the L2

formula to approximate Caputo derivatives. Sivalingam et al. [

33] applied the theory of functional connection to solve Caputo-type problems. Guo et al. [

34] used a Monte Carlo strategy to approximate fractional derivatives. Subsequent studies continue to use different numerical schemes to solve FPDEs [

35,

36,

37].

The advection–diffusion equation can effectively characterize transport processes in both engineering and natural phenomena. However, the description of transport processes in various physical or biological systems often exhibits anomalous diffusion behavior. For instance, particle propagation speed deviates from Fick’s law, and the growth rate of mean square displacement shows a nonlinear relationship with time. These phenomena also occur in other transportation scenarios, such as pollutant migration, groundwater flow, and turbulent transport. The fractional advection–diffusion equation can more accurately describe these complex dynamic processes. The fractional derivative utilizes a memory kernel in the form of a power function to weight the entire historical process, which gives the model a memory effect and significantly improves its ability to model and predict transport behavior in complex systems, attracting widespread attention.

As a significant extension of fractional derivatives, distributed-order derivatives break through the limitation of fixed-order derivatives and expand the derivative order from a single numerical value to a continuous interval description based on distributed functions. Although this feature enhances the ability of equations to describe complex physical processes, it also increases the difficulty of solving them. To address this challenge, some scholars have drawn on the discretization idea of fractional derivatives in fPINN. In the recently proposed PINN-based framework, Ramezani et al. [

38] used composite midpoint and L1 formulae to approximate the distributed-order derivative, while Momeni et al. [

39] combined the Legendre–Gauss quadrature rule and operational matrices to discretize the distributed-order derivative. Other scholars also use numerical schemes to convert the distributed-order derivatives into a processable form, and then embed them into a neural network [

40,

41,

42,

43].

However, there are two issues with this approach: (1) PINN-based frameworks rely on numerical schemes such as finite difference to discretize the distributed-order derivative; (2) the approximation of the distributed-order derivative cannot be achieved by optimizing the parameters of the network. Therefore, the accuracy of the solution is limited by the precision of the numerical discretization method, rather than the approximation ability of the network. These issues drive the primary objective of this work.

In this paper, we present a new framework based on the PINN, called SVPINN, to solve the distributed-order time-fractional advection–diffusion equation. The proposed method changes the integral form by separating variables, which allows the neural network to directly approximate the distributed-order derivative. The main contributions of this paper are as follows: (1) We propose a variable separation-based PINN framework suitable for the distributed-order derivative. Unlike the classical separation of variables method that seeks analytical solutions, a neural network is utilized to approximate the variable-based basis functions to achieve the variable separation process, as the kernel function in the Caputo derivative is not strictly separable. (2) The proposed SVPINN decomposes the kernel function in the Caputo derivative into the product form of basis functions consisting of time variable, integral variable, and order. This avoids using a numerical discretization scheme to approximate the distributed-order derivative, thereby eliminating integral discretization. (3) In the SVPINN framework, the approximation of the distributed-order derivative is gradually completed by training the parameters of the network during the training process, which is different from the PINN-based frameworks proposed in [

40,

41,

42,

43] that directly complete the approximation of the distributed-order derivative using a numerical scheme before the training process. (4) Compared with the PINN that simulates the fractional derivative using numerical discretization scheme, the SVPINN significantly improves prediction accuracy and convergence speed in irregular domains and high-dimensional problems.

The structure of this paper is as follows: In

Section 2, the detailed framework of the SVPINN is presented. In

Section 3, several numerical examples are used to test the performance of our proposed method. In

Section 4, we summarize several concluding remarks.

3. Results

In this section, several numerical experiments are studied to illustrate the performance of the proposed method. To assess the capability of the SVPINN method, the relative

error is formulated as

where

denotes the predicted solution. For convenience, we define

and

.

In the absence of a specific statement, the network consists of 4 hidden layers and 10 neurons on each hidden layer, the activation function is the tanh function, and the parameters and are set to 1000 and 2000, respectively. The test data are 10,000 points randomly selected from the solution domain using the Latin Hypercube Sampling strategy. We choose the L-BFGS optimizer to update the trainable parameter .

Remark 3. The L-BFGS automatically determines the optimal step size for each iteration during the training process, so there is no need to set a learning rate. And its convergence criterion is that the gradient norm of the iteration point or the change in adjacent objective function values is less than the preset threshold.

The analytical solution for the problem (

1)–(

3) is as follows

Given

, the boundary condition

, initial condition

, and source term

are given by the exact solution. We compare the SVPINN with the PINN based on the

FBN-

scheme [

43,

45,

46,

47] (PINN-FBN) and the PINN based on the WSGD operator [

48,

49] (PINN-WSGD). Both methods approximate the distributed-order derivative by discrete schemes and then use the PINN to solve the problem (

1)–(

3). The structure of the two discrete schemes and parameter settings are presented in

Appendix A.

3.1. Feasibility Analysis

In this example, we aim to adopt a function approximation case to validate the feasibility of the proposed variable separation method for the kernel function. Consider the following function:

For this function, we decompose it as follows

where

and

. We construct a network

to predict the basis function

. Then the loss function is formulated as

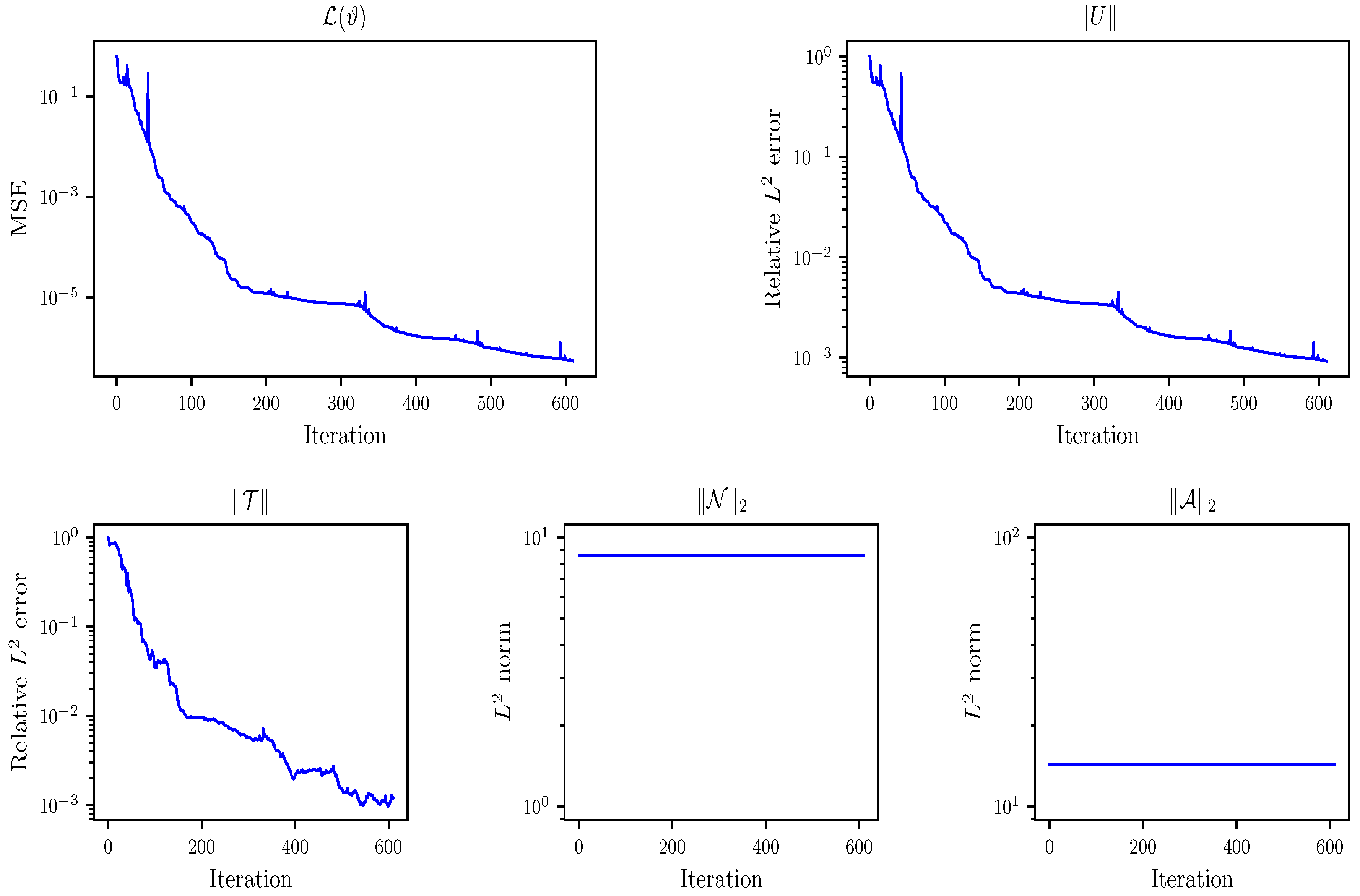

The history of the loss function

and the relative

error

during the training process is presented in

Figure 1. From the decreasing trend of the loss function and the error, the proposed method of decomposing the kernel function into three basis functions is validated as feasible. It also illustrates the stability of the method during the training process. Moreover, we also display the dynamic change in the relative error of the basis function

and the

norm of the basis functions

and

during the training process in

Figure 1. It can be observed from the figure that the network

provides an ideal level of prediction accuracy. Since the basis functions

and

are only related to

y and

z, respectively, their norms remain fixed during the training process. Based on the above analysis, it can be demonstrated that our proposed neural network-based variable separation method for the kernel function is reasonable.

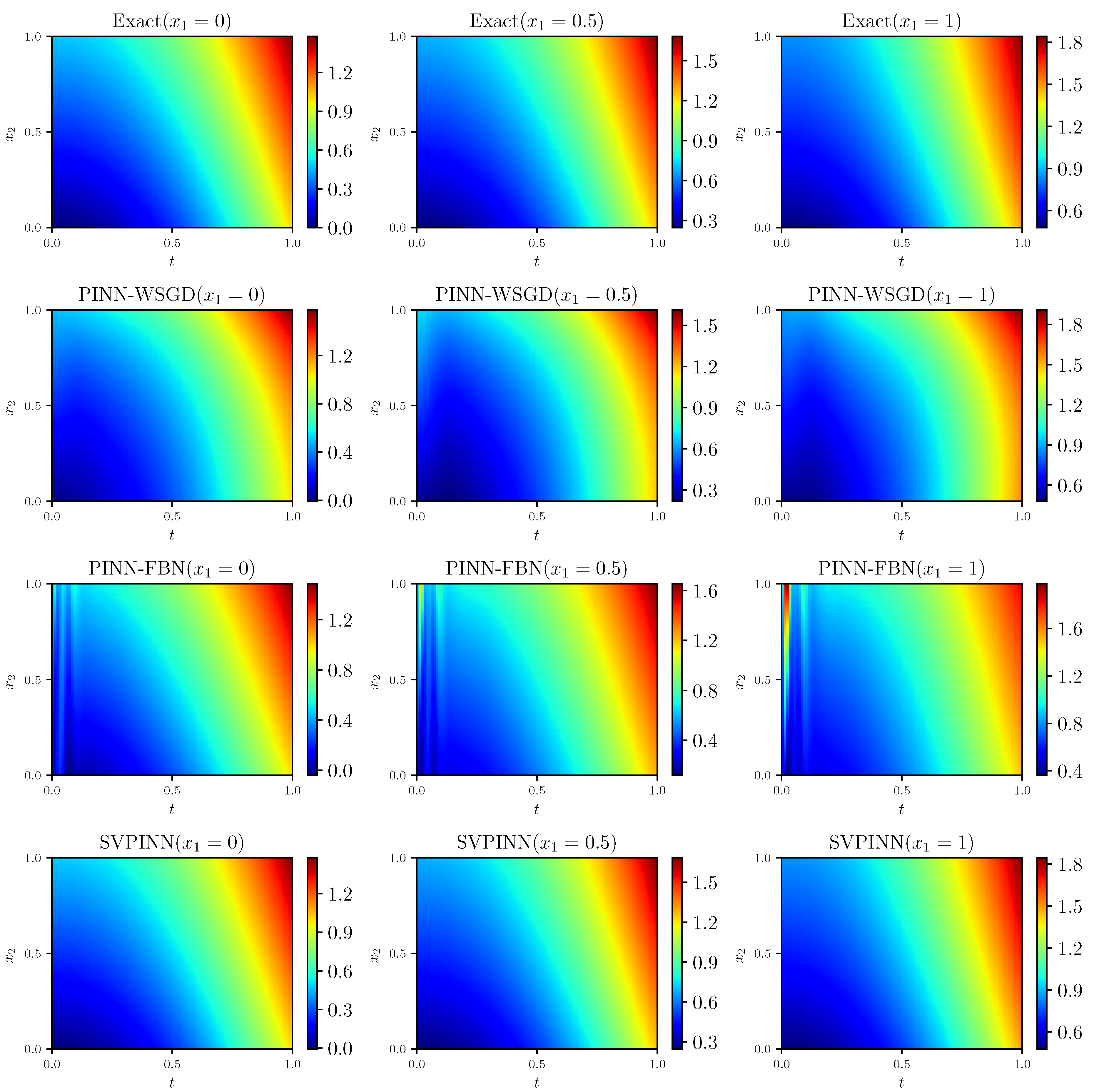

3.2. 2D Problem

For this example, we set

and

.

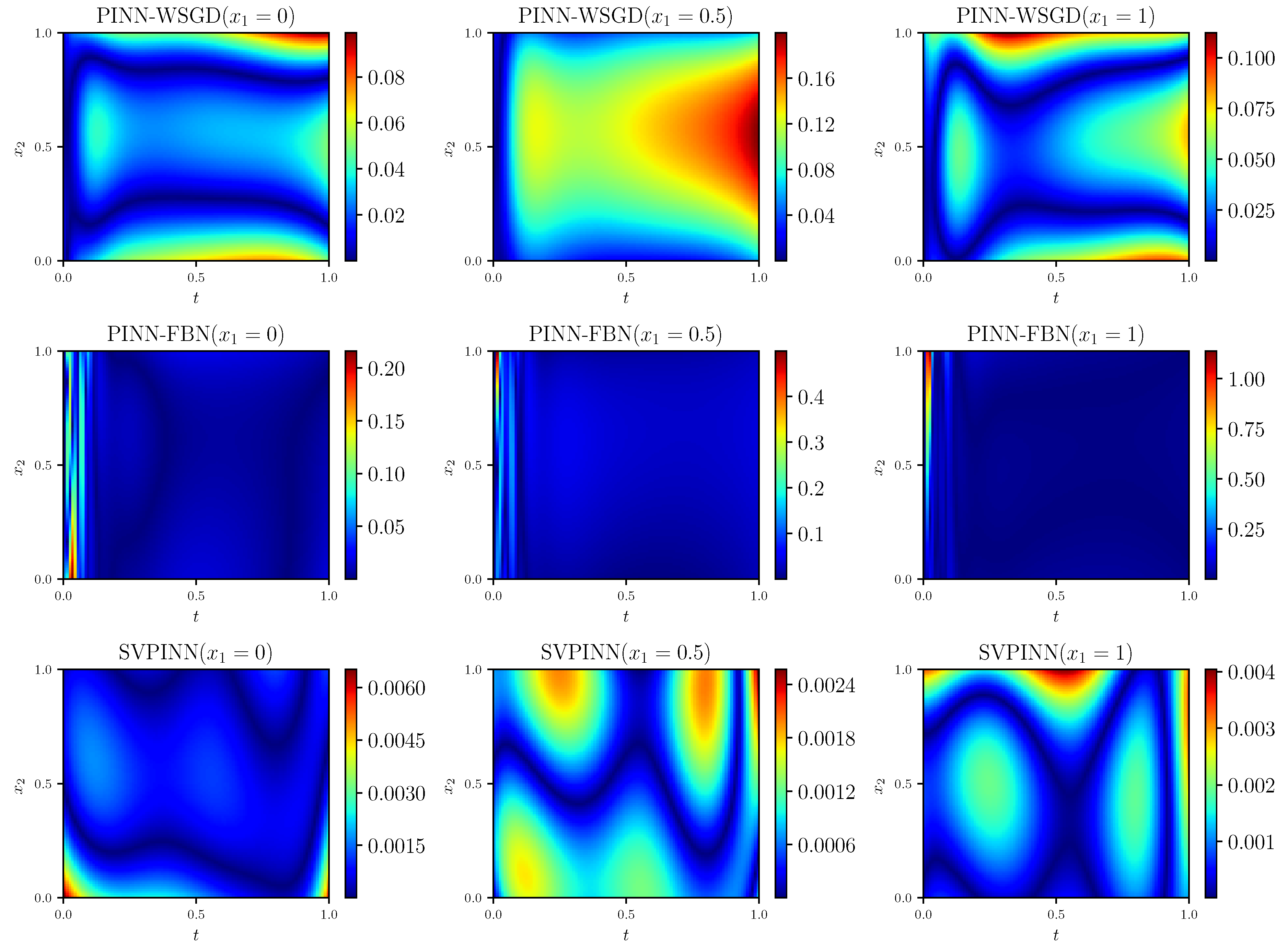

Figure 2 displays the solutions predicted by the SVPINN, PINN-FBN, and PINN-WSGD methods. Moreover, the corresponding absolute error between the predicted and exact solutions is depicted in

Figure 3. It reveals that the proposed method can obtain better prediction accuracy.

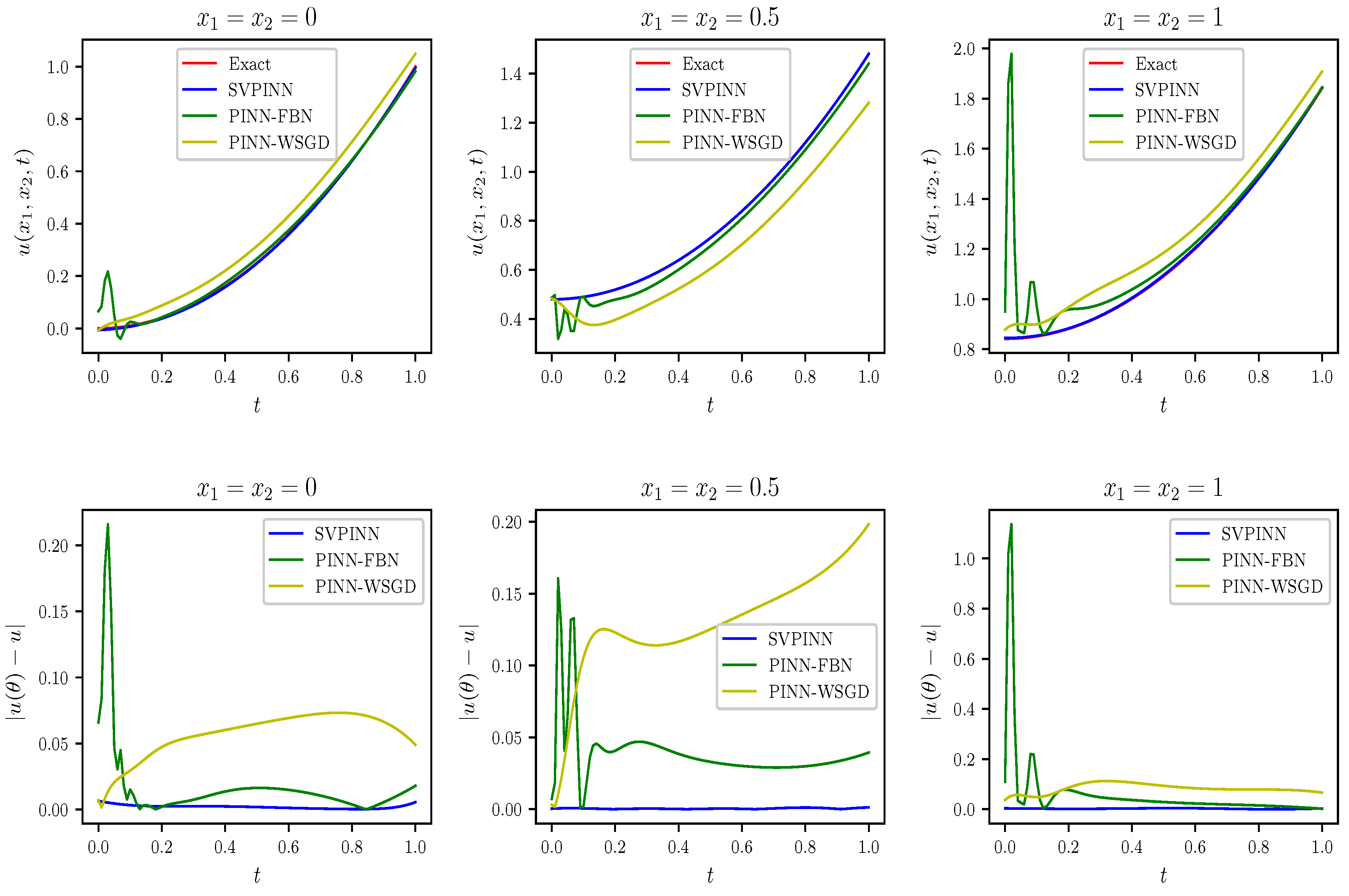

Figure 4 provides a more explicit comparison between the SVPINN, PINN-FBN, and PINN-WSGD, illustrating that the proposed SVPINN is closer to the exact solution.

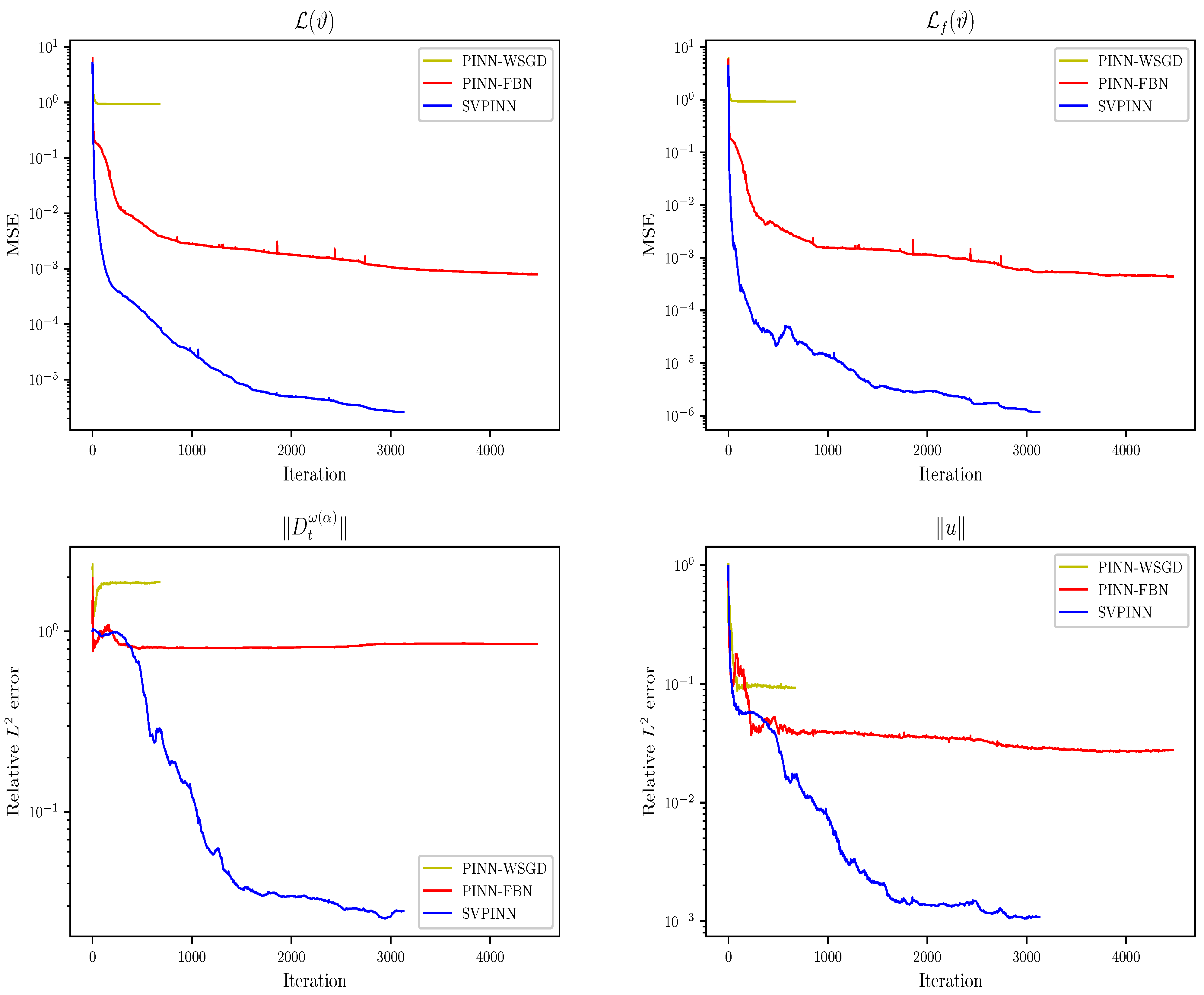

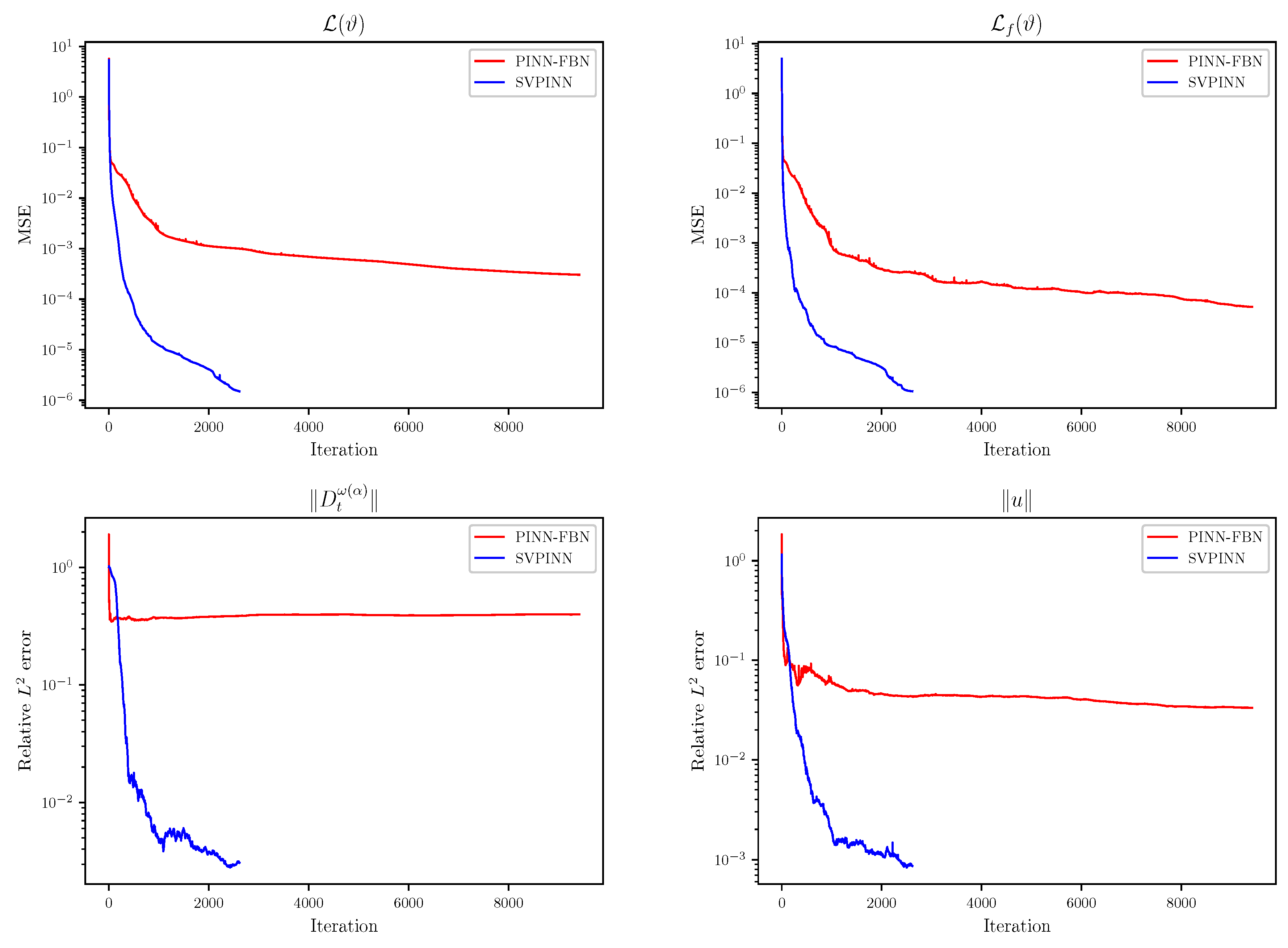

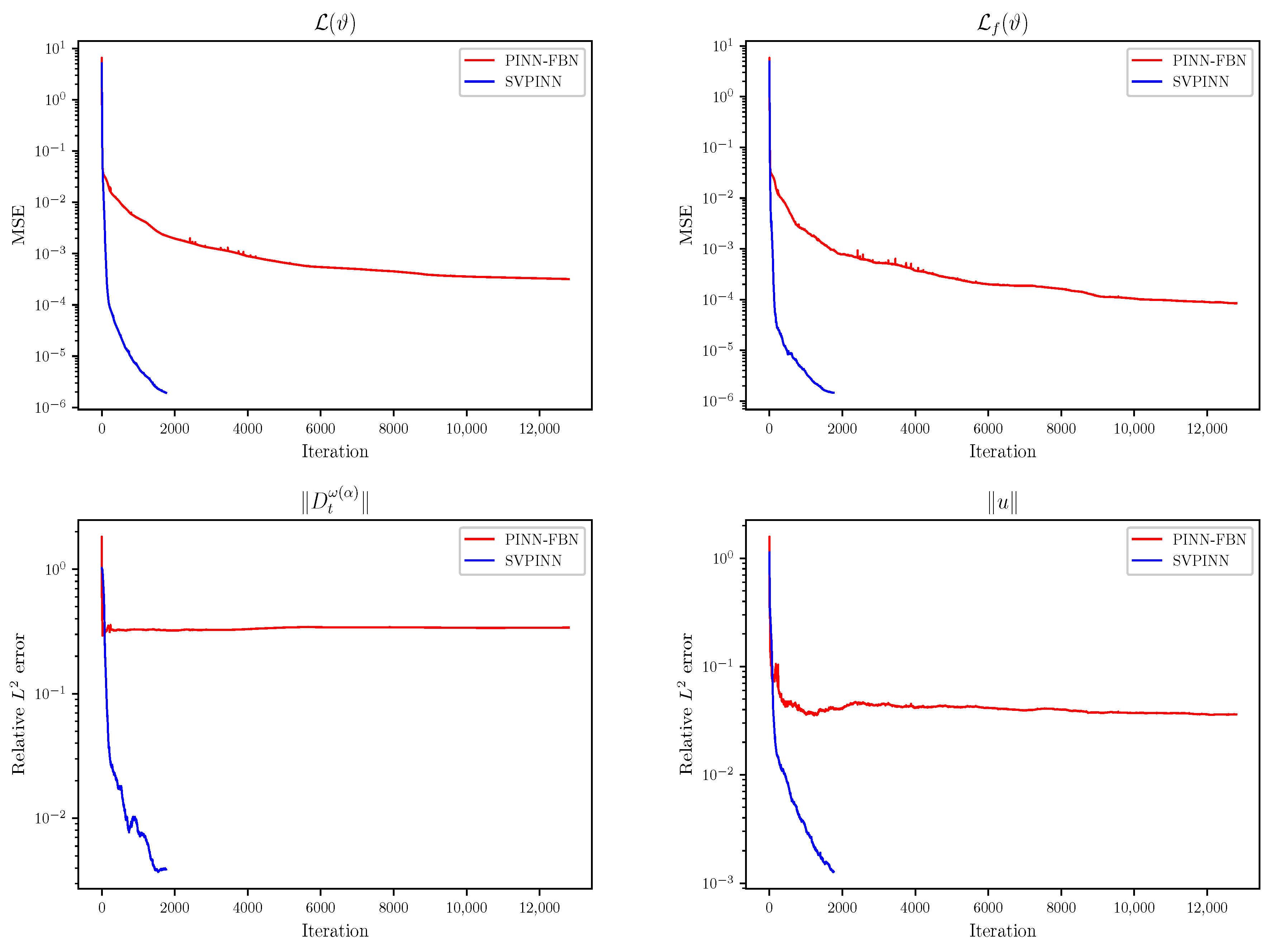

Figure 5 presents a comparative analysis of the SVPINN, PINN-WSGD, and PINN-FBN methods, which depicts the dynamic changes in the total function

, loss term

, and relative errors. This figure demonstrates that the PINN-WSGD has poor convergence performance in solving FPDE (

1), making it difficult to effectively reduce errors and achieve efficient and accurate prediction. Although the PINN-FBN can solve the problem (

1), its convergence speed is relatively slow during the training process, and more iterations are required to reach the same level of accuracy. Compared to the PINN-FBN, the SVPINN exhibits better performance and faster convergence speed. It can achieve a lower mean square error with fewer iterations and achieve a more ideal prediction result.

In

Table 1 and

Table 2, we present our ablation study on the key components of the three PINN methods, such as the network structure and number of training points, and quantitatively analyze their impact on the accuracy, convergence speed, and generalization ability of the model by adjusting parameters. The training time represents the CPU time. From

Table 1, it can be found that our proposed method significantly outperforms the PINN-FBN and PINN-WSGD methods in prediction accuracy, while maintaining comparable memory usage. In terms of convergence speed, the SVPINN has the potential to accelerate convergence under appropriate network structures. The PINN-WSGD has a short computation time but fails to achieve effective convergence, while the PINN-FBN generally takes a long time to converge.

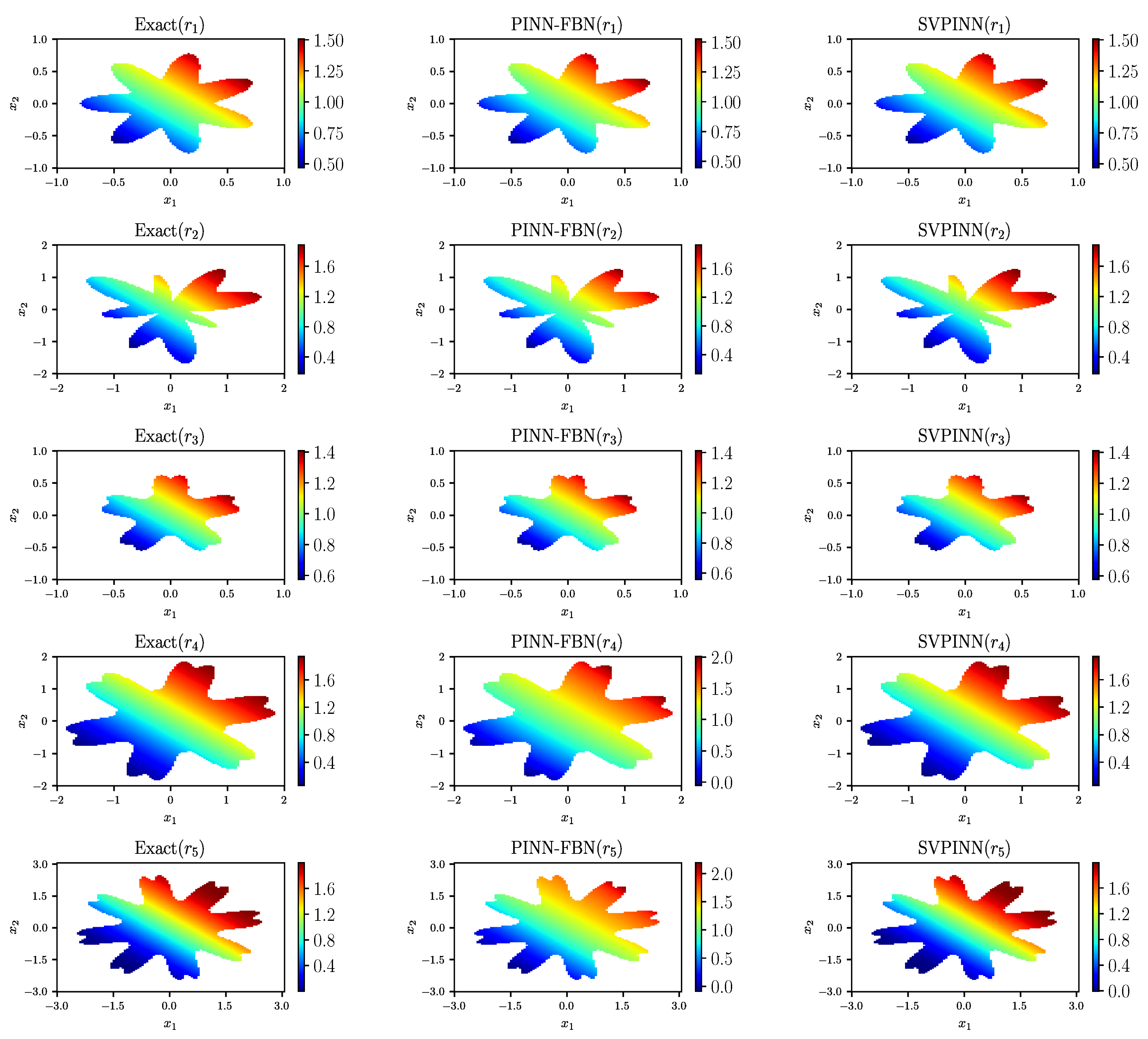

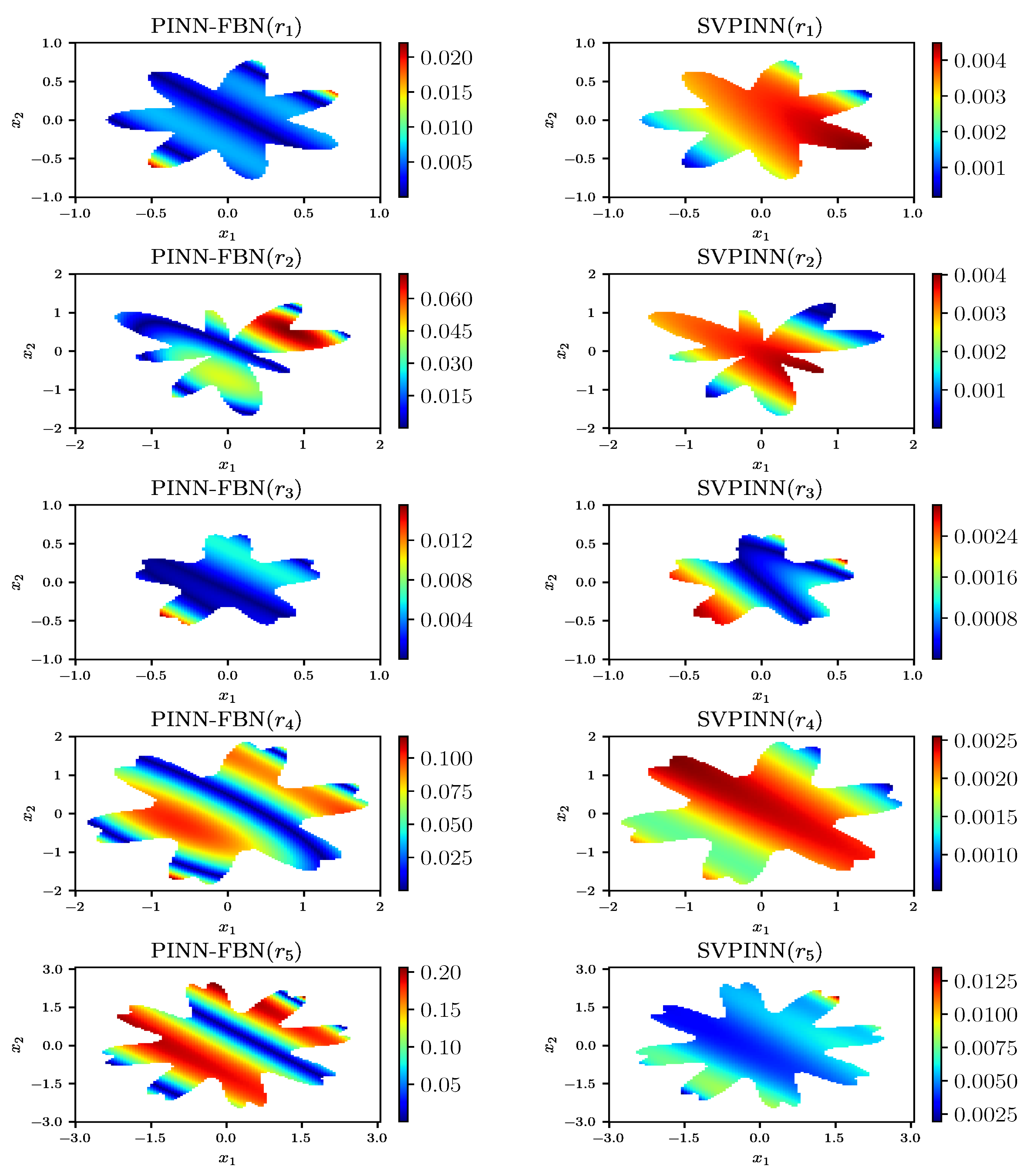

3.3. Irregular Domain

To systematically evaluate the adaptability and solving capability of the SVPINN in complex geometric scenes

we select five irregular domains as the research object. The parametric equations of these domains are as follows

The time interval is the same as that in

Section 3.2.

Table 3 reports the relative

error and calculation cost provided by the SVPINN, the MoPINN [

43], and the PINN-FBN. From the table, it can be seen that the relative error of our proposed method always remains between the levels of

and

, which are one and two orders of magnitude higher than the prediction accuracy of the other two methods. The results demonstrate that our proposed method can better predict the exact solution.

Figure 6 presents the predictions given by the proposed SVPINN and the PINN-FBN, and

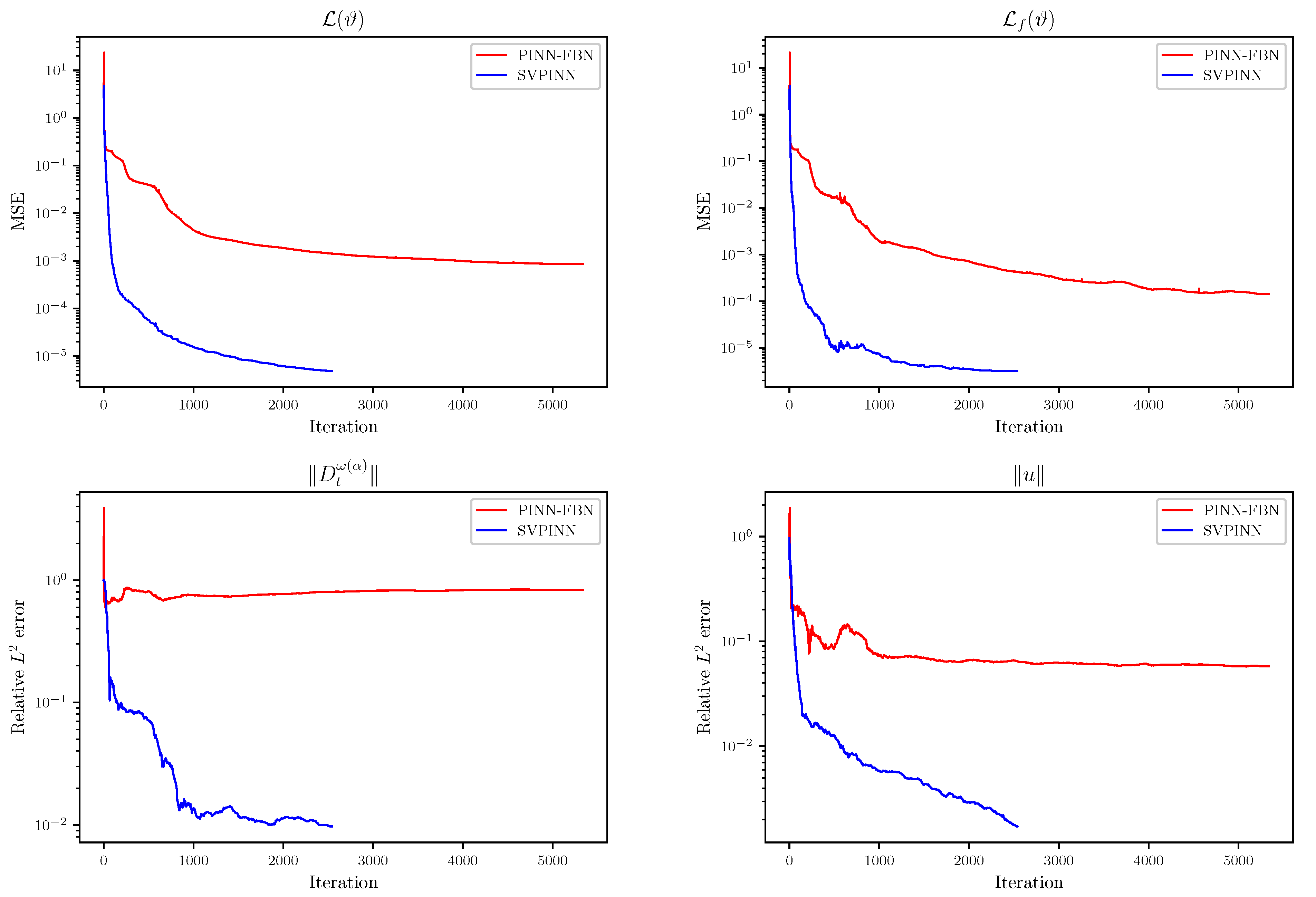

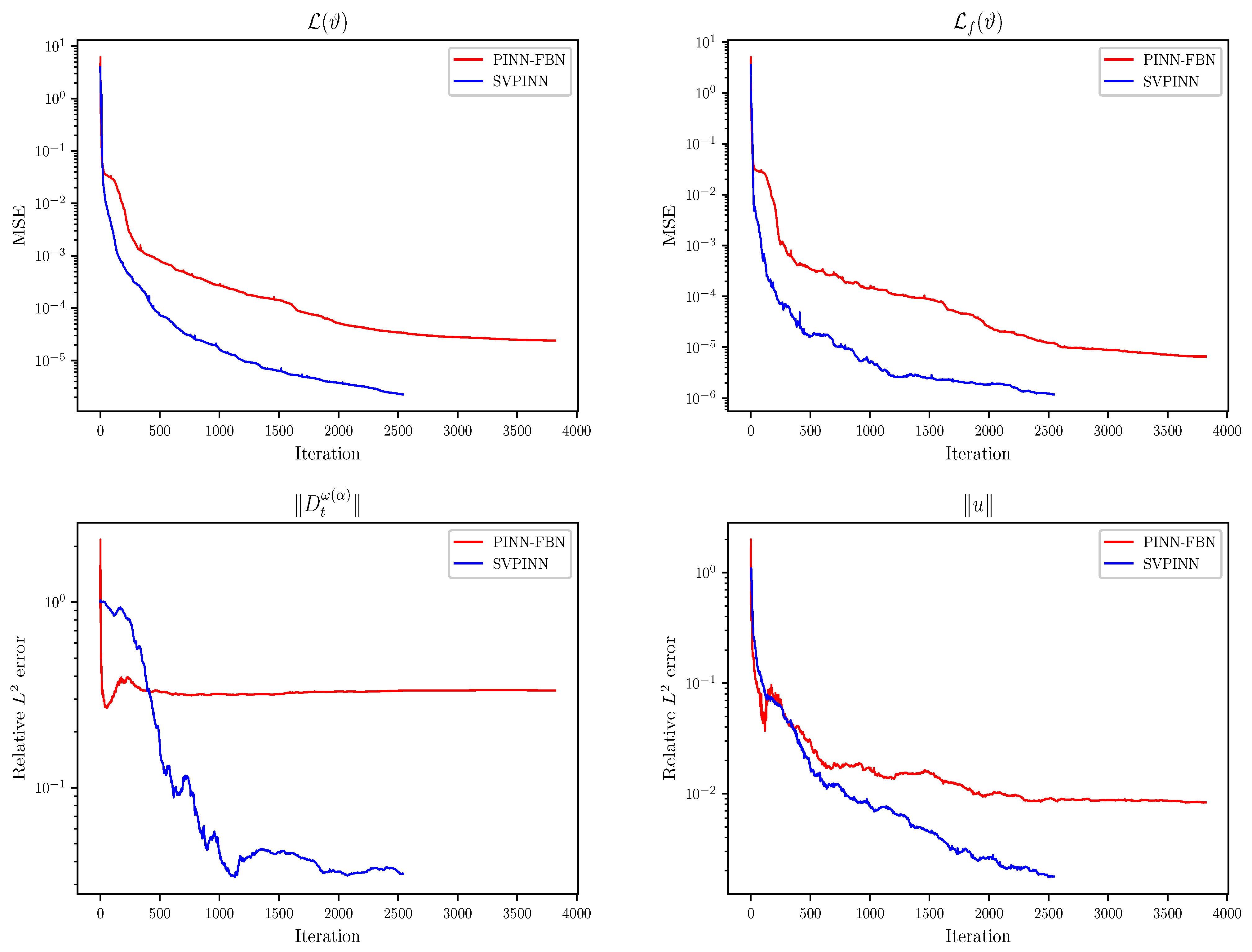

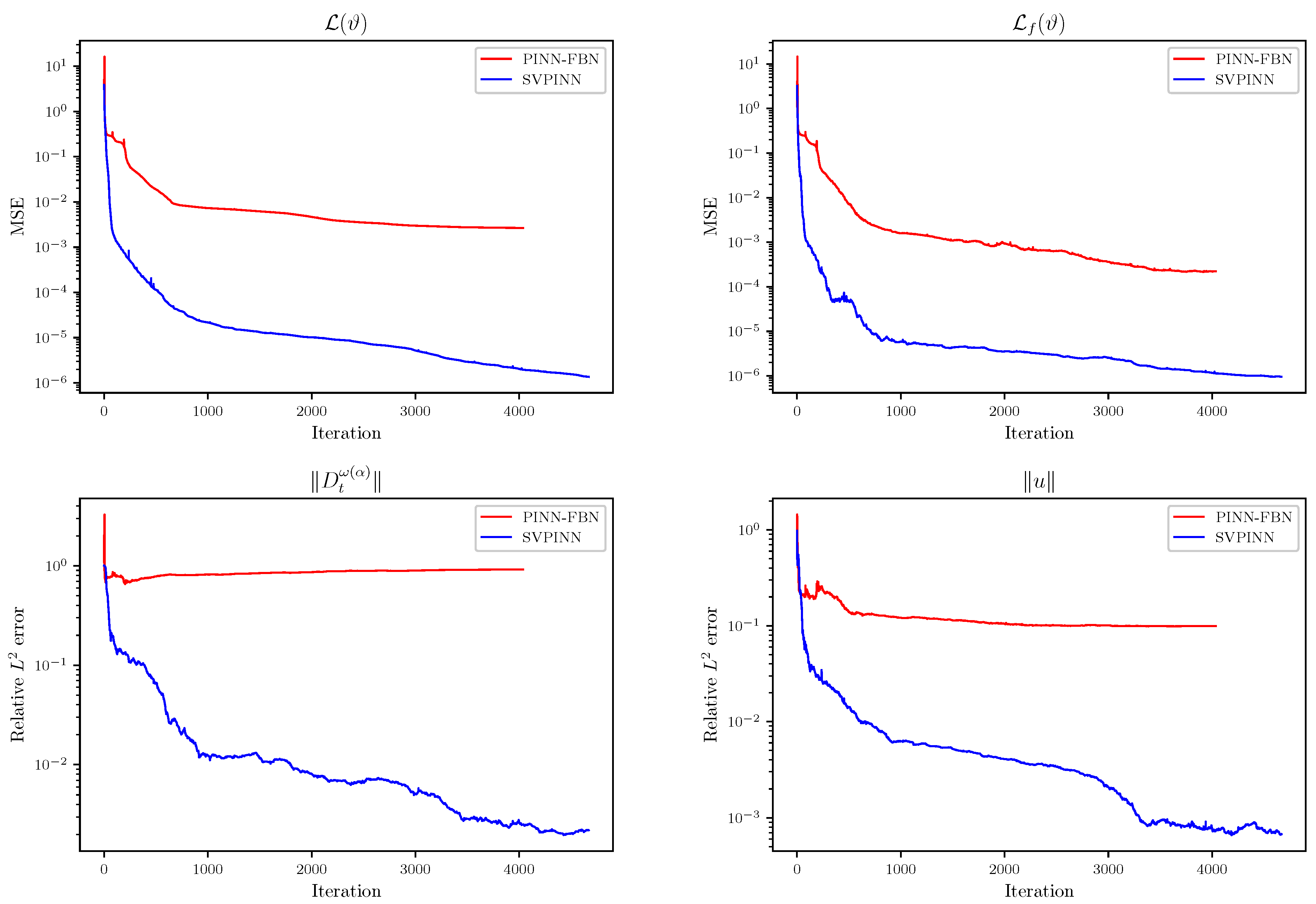

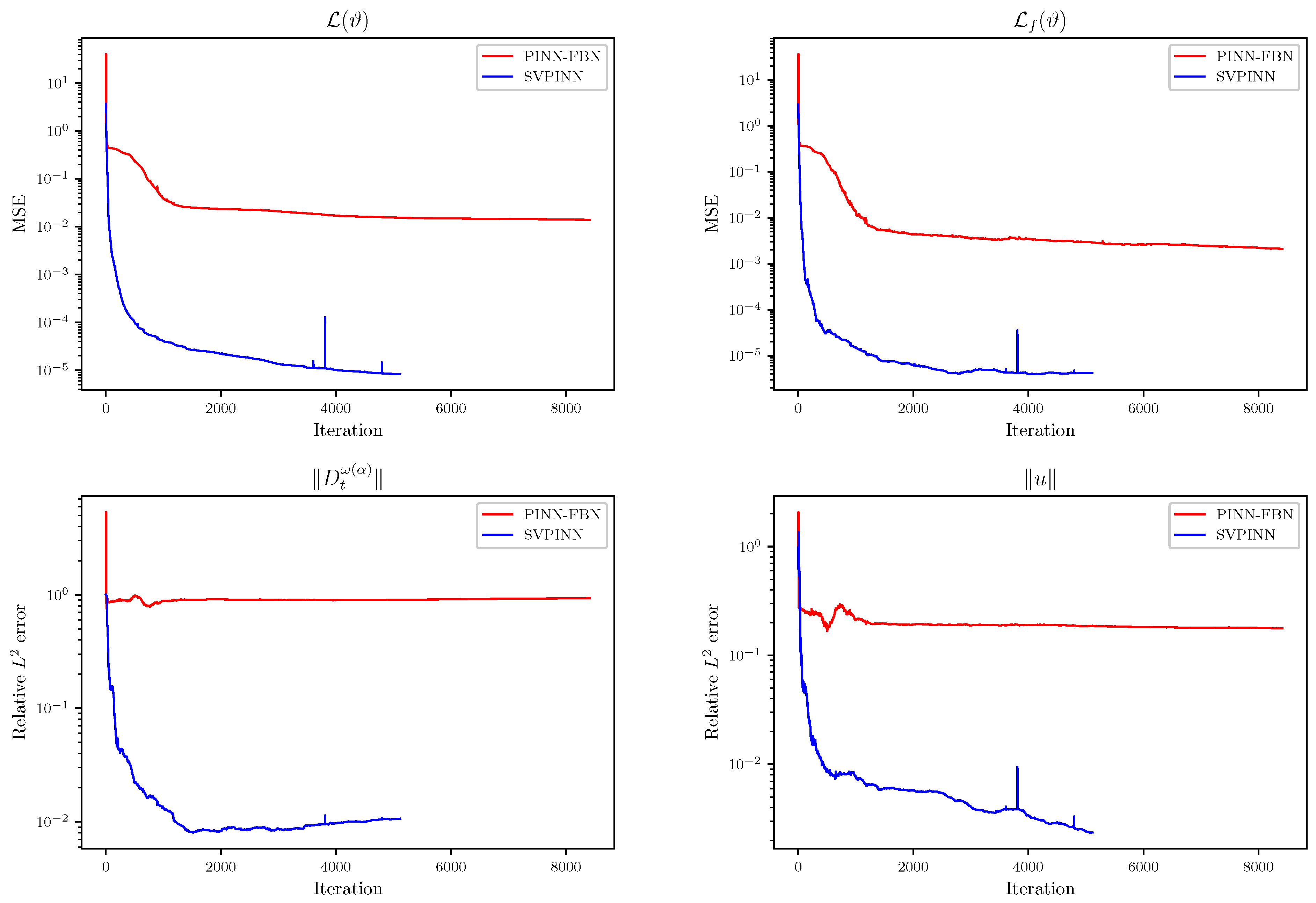

Figure 7 displays the distribution of the absolute error between the exact solution and the prediction. From the figure, it can be observed that the prediction results of our proposed method have higher consistency with the exact solution, which intuitively verifies the effectiveness of the proposed SVPINN in solving the distributed-order advection–diffusion equation with irregular domains. To evaluate the feasibility of the SVPINN by monitoring the changes in the loss function during the training process and demonstrate physical consistency via a quantitative analysis of the residual equation and the errors,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 display the decreasing trend of the loss function

, the loss term

, and the relative errors of the distributed-order derivative

and the exact solution

in the process of optimizing the network. In general, the SVPINN has more advantages in the optimization effect. It not only performs better than the PINN-FBN in reducing the loss, but also converges faster and can reach a lower error level. Moreover, we also test the impact of network parameters, the number of collocation points, and the number of the initial and boundary points on the performance of the SVPINN in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7. From the table, it can be seen that the relative error of the SVPINN is generally maintained at the level of

to

, which are one and two orders of magnitude lower than the other two methods. The SVPINN has excellent advantages in computational efficiency. The data in the table clearly indicates that the training time required by the SVPINN is significantly shorter than that of the PINN-FBN, often as little as

or even less. Furthermore, the SVPINN achieves higher accuracy without incurring additional memory consumption, maintaining essentially the same memory usage as the PINN-FBN. When the hyperparameters change, the error of the SVPINN consistently stays at the order of

, indicating its strong stability.

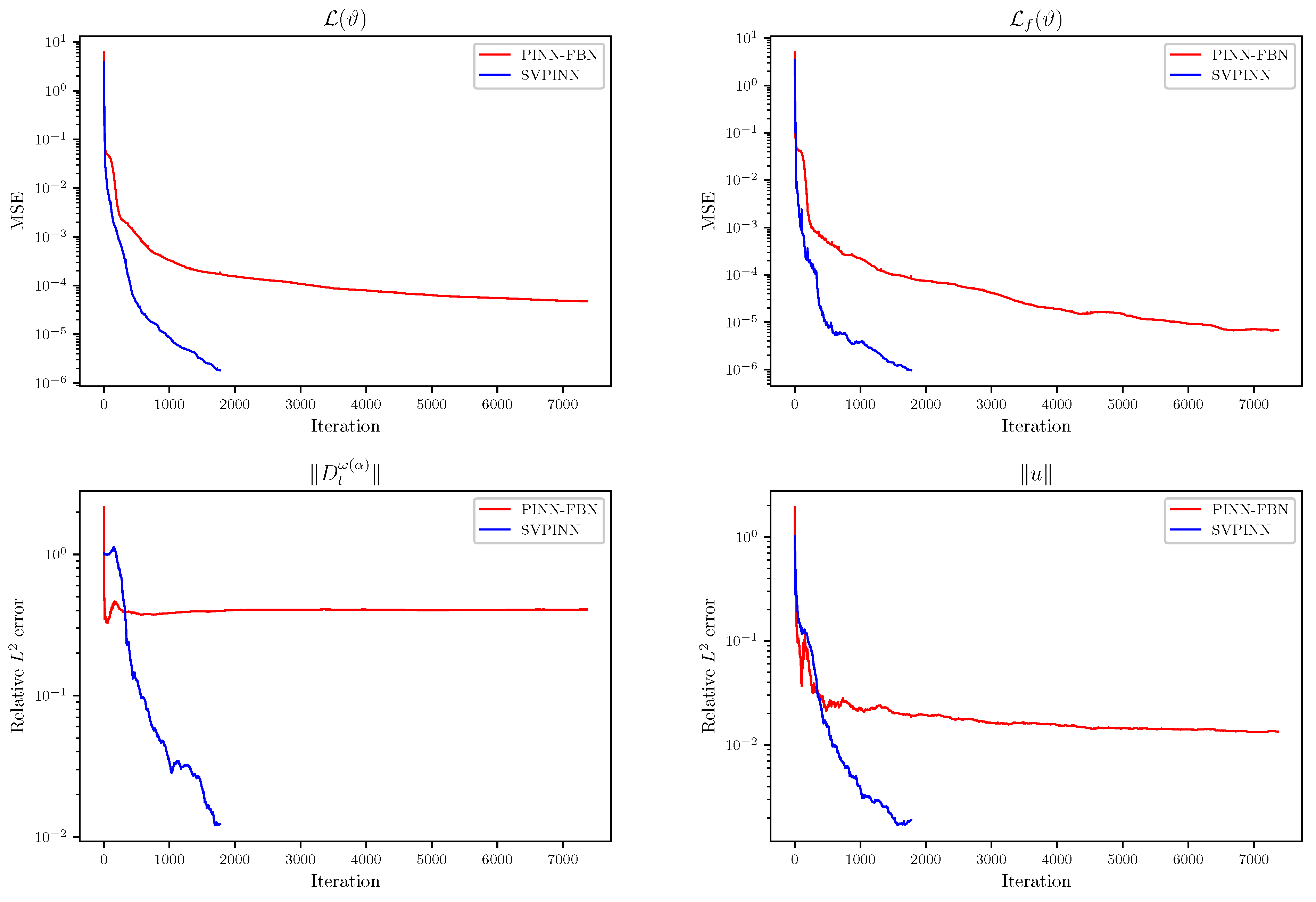

3.4. High-Dimensional Problems

In this example, we investigate the effectiveness of the SVPINN for high-dimensional distributed-order advection–diffusion equation. The spatial domain and time interval are set to and , respectively.

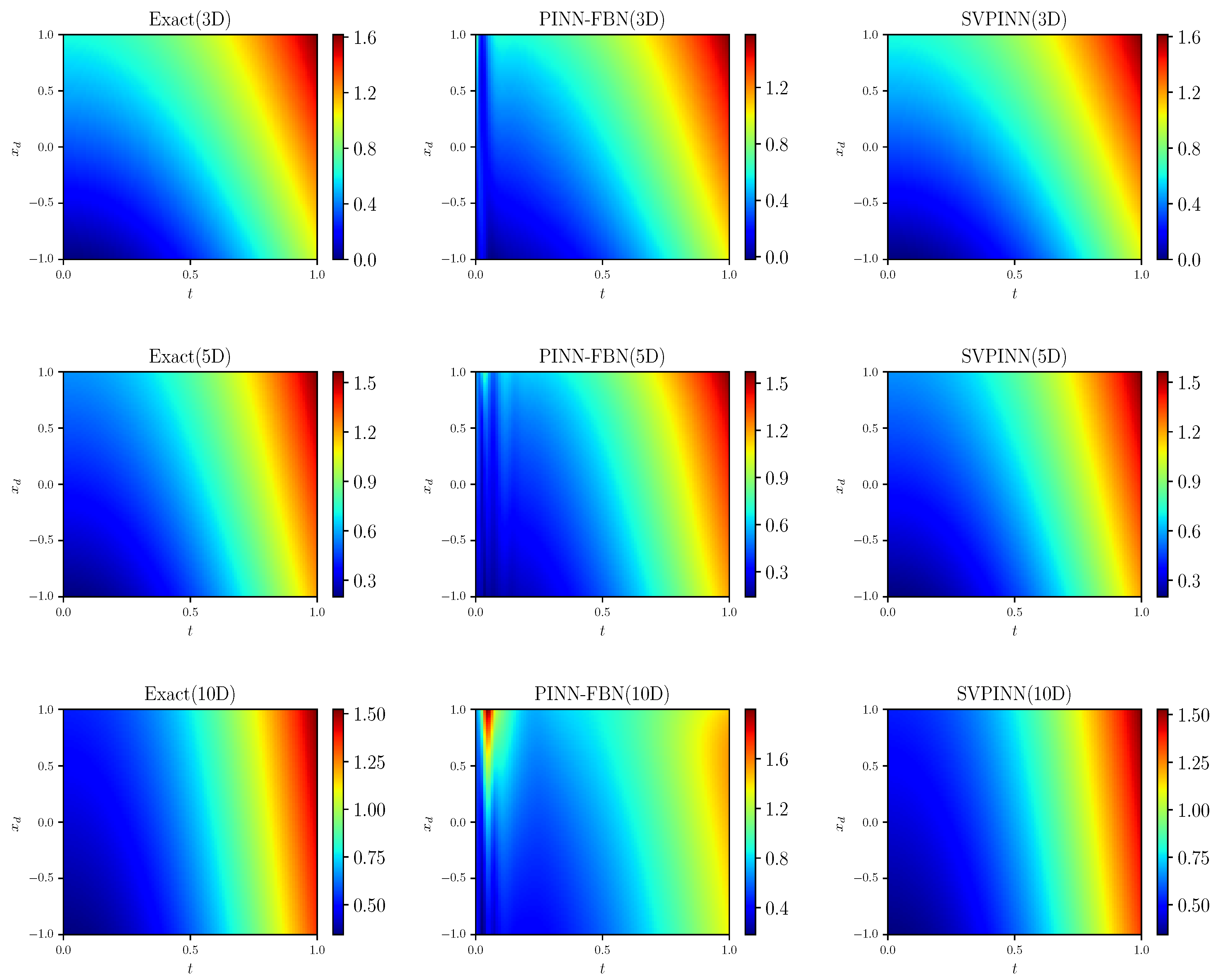

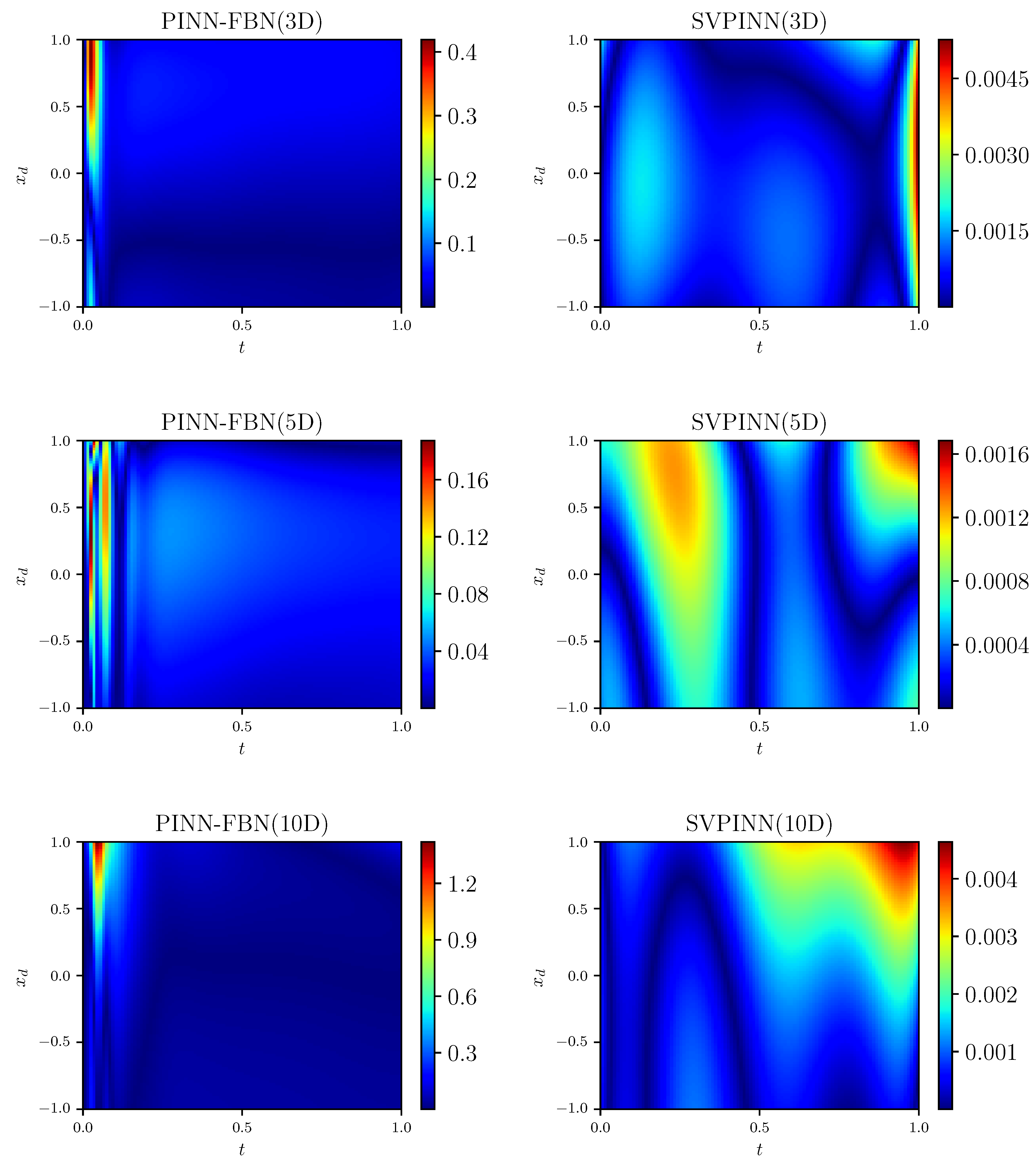

In

Table 8, we present the relative

error, training time, and memory usage obtained by the SVPINN and PINN-FBN methods at

. The error between the exact solution and the prediction given by the SVPINN is

, when

. The results demonstrate that for high-dimensional cases, our proposed method also has good prediction accuracy. In

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, we plot the distributions of the analytical solution, the prediction, and the absolute error. In addition, we provide a comparison of the loss and relative error between the SVPINN and PINN-FBN methods in

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17, which shows that the SVPINN has higher accuracy in approximating the distributed-order derivative and can better optimize the network parameters. During the training process, we can observe a stable decrease and rapid convergence of the total loss function, demonstrating the feasibility of the proposed SVPINN. Quantitative analysis of the loss of the residual equation and the relative error, as shown in the figures, verifies that the neural network adheres to the physical laws described by the governing equation during the training process.

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12 report the performance of the SVPINN and PINN-FBN methods with respect to the network structure, the number of collocation points, and the number of initial and boundary data. From the table, it can be seen that the prediction accuracy of the PINN-FBN is maintained at the level of

, while that of the SVPINN is maintained at the level of

. The training time for the SVPINN is generally maintained between 20 s and 100 s, while the PINN-FBN requires approximately 60 s to 800 s, which is 3 to 8 times longer than the SVPINN. When the network structure and the number of training points change, the prediction accuracy of the SVPINN remains almost stable at the level of

, demonstrating strong robustness.

3.5. Comprehensive Analysis

In this section, to further comprehensively evaluate the performance and the computational complexity of the proposed method, we summarized, in

Table 13, the key indicators such as prediction accuracy, computation time, and memory, which reflect the overall performance of SVPINN in

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4. As shown in the table, in

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4, our proposed method not only achieves better prediction accuracy, but also has lower memory consumption than the PINN-FBN. Moreover, the SVPINN significantly improves computational efficiency with similar computational costs, reducing training time to

to

of that required by the PINN-FBN. Although the PINN-WSGD has less training time than the SVPINN, it fails to accurately predict the exact solution. Overall, our proposed method shows better performance in both prediction accuracy and computational cost, while also exhibiting lower computational complexity and excellent scalability.