1. Introduction

Modern learning institutions, notably higher education institutions, operate in a highly competitive and complex environment with the availability of the World Wide Web. Many online courses are available for students to study after hours or learn something new entirely through different e-learning platforms such as intelligent tutoring systems (ITS), learning management systems (LMS), and massive open online courses (MOOC). The competitive environment has led to several opportunities for the survival of higher education institutions. Despite these advancements in the education field, universities face challenges in increased student dropout rates, academic underachievement, graduation delays, and other persistent challenges [

1,

2]. Therefore, most institutions focus on developing automated systems for analyzing their performance, providing high-quality education, formulating strategies for evaluating the students’ academic performance, and identifying future needs.

Globally, a particular aspect of possibilities was focused on the concept of special education just over ten years ago. It debuted immediately after the International Conference on Education’s 48th meeting, which had the topic “Inclusive Education: The Way of the Future”. This conference was organized in Geneva in (2008), and they focused on providing education to hundreds of people with special needs globally, who had low or no access to educational opportunities or they are special or at risk of dropping out due to their mental, physical, or emotional state [

3]. The long-term goal was to assist the Member States of UNESCO in providing the political and social education that every individual requires to practice their human rights and avoid fifth generation warfare [

4]. Globally, a significant concern of the education stakeholders, such as policymakers and practitioners in the educational domain, is the rate of students’ dropout [

5,

6,

7].

Chung and Lee [

8,

9] suggested that students who drop out add to the social cost through conflicts with peers’ family members, lack of interest, poverty, antisocial behaviors, or inability to adapt to society. OuahiMariame et al. [

10] suggested that the academic performance of the student is the primary goal of educational institutions. Failing to sustain or even improve the retention rate would negatively impact students, parents, academic institutions, and society as a whole [

11]. This puts the performance of students as a vital factor that must be enhanced by all necessary means.

Educational data mining (EDM) can help to improve the academic performance of the students in the academic institutions [

10]. One of the most valuable solutions to increase the students’ retention rate in any academic institution is monitoring students’ progress, and identifying students with special needs, or detecting at-risk students for early and effective intervention [

12]. According to OuahiMariame et al. [

10], EDM can help in predicting student achievement in advance, so it facilitates academic performance tracking. Early identification of such students triggers educators to propose relevant remedial actions and prevent unnecessary dropout risks effectively [

5,

13]. Thus, the identification of at-risk students has been a significant development in several studies [

12,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

A plethora of works can be found on the subject. For many years, government officials, policymakers, and educational institutions’ heads have been trying their best to have a robust mechanism that may assist the teachers in identifying the special or at-risk students. Examples, such as [

5,

6,

12] are prominent. However, most complex methods use expensive hardware, are extremely data-dependent, and make predictions only. There is a lack of having a robust system with low complexity, which can be used as a warning system for the teachers to identify the students with special needs without having to use complex data-basis and expensive hardware. Moreover, the end goal is to ensure that every student gets an equal opportunity for education and a better future, so a precise warning system with low false detection and high accuracy should be made available at a low cost. To the best of our knowledge, there is no such rule-based system that works with all the constraints for student monitoring.

In this paper, we have proposed a rule-based model that directly considers the student’s achievement in each assessment component when received. It also adopts a dynamic approach that is visualized, adaptive, and generalized for any data set. The proposed solution will allow universities to evaluate and predict the student’s performance (especially at-risk) and develop plans to review and enhance the alignment between planned, delivered, and experienced curriculum. The ultimate objectives of this paper are as follows:

Propose a customized instructor rule-based model to identify at-risk students in order to take appropriate remedial actions.

Propose a warning system for instructors to identify at-risk students and offer timely intervention using a visualization approach.

The rest of the paper is organized in the following manner. In

Section 2 the literature review of identifying students’ performance is described.

Section 3 explains the data set concerning data collection and data pre-processing. Moreover, it provides the implementation details in terms of data exploratory analysis.

Section 4 explains the proposed customized rule-based model to identify at-risk students as well as visualization of results.

Section 5 highlights some discussion and future work. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

In addition, accurate prediction of student performance highlighted in [

12,

19] also helps instructors identify under-performing students requiring additional assistance. Early prediction systems for at-risk students have been applied successfully in several educational contexts [

20]. The authors in [

12] proposed and evaluated an intuitive approach to detect academically at-risk students using log data retrieved from various learning management systems (LMS), which has been commonly used to identify at-risk students in learning institutions [

21,

22]. The students use the LMS to manage classes, conduct online exams, connect with the instructor, use an e-portfolio system, and check the self-learning contents. A log file with a student ID, the date operated, and the type of activity are recorded by the LMS whenever a student uses the system. A private liberal arts university in Japan uses LMS across all the programs offered within the university, and it records a log file whenever a student operates the system. Therefore, all the log files collected between 1 April and 5 August 2015 are considered. A total of 200,979 records were available. A typical record contained a student ID, date of access, and the type of activity. The level of students’ commitment to learning is expected to be indicated by the level of LMS usage.

Meanwhile, the authors of [

5] sought to develop an early-warning system for spotting at-risk students using eBook interaction logs. The system considers digital learning materials such as eBooks as a core instrument of modern education. The data were collected from Book-Roll, an eBook service that over 10,000 university students in Asia use to access course materials. The study involved 65,000 click-stream data for 90 students enrolled in a first-year university taking an elementary informatics course. A total of 13 prediction algorithms with data retrieved within 16 weeks of the course delivery were utilized to determine the best performing model and optimum time for early intervention. The performances of the models were tested using 10-fold cross-validation. The findings showed that all models attained their highest performance with the data from the 15th week. The study showed a successful classification of students, with an accuracy of 79%, in the third week of the semester.

Similarly, Berens et al. [

6] studied the early detection of at-risk students using students’ administrative data and machine learning (ML) techniques. They developed a self-adjusting early detection system (EDS) that can be executed at any time in a student’s academic life. The EDS uses regression analysis, neural networks, decision trees, and the AdaBoost algorithm to identify essential student characteristics that identify potential student dropouts. The EDS was developed and tested in two universities to predict at-risk students accurately; (1) A state university (SU) in Germany with 23,000 students offering 90 different bachelor programs, and (2) a private university of applied science (PUAS) with 6700 students and 26 bachelor programs. At the culmination of the first semester, the prediction accuracy for SU and PUAS was 79% and 85%, respectively. This prediction accuracy has been improved to 90% for the SU and 95% for the PUAS at the end of the fourth semester. Thus, the utilization of readily available administrative data is a cost-effective approach to identifying at-risk students. However, this technique may not identify the difficulties faced by these students for successful intervention.

At the same time, Aguiar et al. [

9] proposed a framework to predict the at-risk high school students. They gained access to an extensive data set of 11,000 students through a partnership with a large school district—they used logistic regression for classification, Cox regression for survival analysis, and ordinal regression methods to identify and classify which students are at high academic risk. While Hussain et al. [

15] investigated the most suitable ML algorithms to predict student difficulty based on the grades they would earn in the subsequent sessions of the digital design course. This study developed an early warning system that allows teachers to use technology-enhanced learning (TEL) systems to monitor students’ performance in problem-solving exercises and laboratory assignments. The digital electronics education and design suite (DEEDs) logged input data while the students solved digital design exercises with different difficulty levels. The results indicated that artificial neural networks (ANNs) and support vector machines (SVMs) achieved higher accuracy than other algorithms and can be easily integrated into the TEL system [

12].

Similarly, Oyedeji et al. [

13] have tested three models: linear regression for supervised learning, linear regression for deep learning, and a five-hidden-layers neural network. The data have been sourced from Kaggle with personal and demographic features. The linear regression showed the best mean average error (MAE) of 3.26. The study of Safaa et al. [

21] investigated the students’ interaction data in an online platform to establish whether students’ academic performance at the end-term could be determined weeks earlier. The study utilized 76 s-year university students undertaking a computer hardware course to evaluate the algorithms and features that best predict the end-term academic performance. It compared different classification algorithms and pre-processing techniques. The key result was that the K-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm predicted 89% of the unsuccessful students at the end of the term. Three weeks earlier, these unsuccessful students could be predicted at a rate of 74%. Meanwhile, the later study by the same authors [

23] has investigated a dataset of university students from various majors (49,235 records with 15 features). However, there was no clear emphasis on the predictive model. Although the findings of Gökhan et al. [

21] provided essential features for an effective early warning system, the method utilized is specific to the online learning systems. The sample size evaluated is also tiny compared to the number of students undertaking the online courses.

Meanwhile, Chung and Lee [

8] have used the random forest to predict the dropout of high school students, and the model achieved 95% accuracy. The data was sourced from the Korean National Education Information System. The dropout status was collected from “school register change” and “the reason for dropout” in the dataset. They used 12 features to predict the student dropout status. At the same time, Gafarov et al. [

24] experimented with the use of various machine learning methods, including neural networks, to predict the academic performance of the students. They compared the performance of the accuracy of the models taking into account the inclusion and exclusion of the Unified State Exam (USE) results. The suggested models performed relatively well except for the Gaussian Naive Bayes. They also tested a variety of different architectures of NN, and the best one accuracy was 90.1%.

Collaborative filtering matrix factorization researchers in [

19,

25] experimented with the student performance in multiple courses to predict the final GPA by considering the student grades in the previous courses. They used a decision tree classifier which is fed with the transcript data. The classification rules yielded helped to identify the courses that have a significant effect on the GPA. Similarly, Iqbal et al. [

26] adopted three ML approaches; collaborative filtering (CF), matrix factorization (MF), and restricted Boltzmann machines (RBM), to predict student’s GPA. They also proposed a feedback model to estimate the student’s understanding of a specific course. The hidden Markov model used widely to model student learning is used to perform well in a specific course. Their dataset was split into 70% for training the model and 30% for the testing. The ML-based classifiers performance was RMSE = 0.3, MSE = 0.09, and mean absolute error (MAE) = 0.23.

Data mining techniques are also considered relevant analytical tools for decision-making in the educational system. The contribution of Baneres et al. [

7] is twofold. First, a new adaptive predictive model is presented based only on the students’ grades and trained explicitly for each course. Deep analysis has been performed in the whole institution to evaluate its performance accuracy. Second, an early warning system has been developed to provide dashboards visualization for stakeholders and an early feedback prediction system for early intervention in identifying at-risk students. A case study is used to evaluate the early warning system using a first-year undergraduate course in computer science. They demonstrated accurate identification of at-risk students, the students’ appraisal, and the most common factors which lead to the at-risk level. There is a consensus among researchers that the earlier the intervention is, the better for the success of the at-risk student [

27]. The investigation of Mduma et al. [

28] is critical to this study as it collected, organized, and synthesized existing knowledge related to ML approaches in predicting student dropout.

Several researchers have revealed that the understanding of student performance-based EDM can help to disclose at-risk students [

2,

11,

29,

30]. The authors in [

31] proposed predictive models derived from different classification techniques based on nine available remedial courses. In the study of OuahiMariame et al. [

10] they have predicted students’ success in an online course. They have used data from Open University Learning Analytics (OULA). Multiple feature selection techniques (SFS, SFFS, LDA, RFE, and PCA) have been tested with different classification methods (SVM, NAIVE BAYE, RandomForest, and ANN). The best performance accuracy was 58% for the combination of SFS and Naive Bayes.

Aggarwal et al. [

32] have compared the prediction results with and without exploiting the demographic data of the students. They have run the experiment on 6807 records of students from a technical college in India. An ensemble predictor was proposed, and it showed a significant increase in performance when the demographic data are used compared to the performance when only academic data was used. The highest accuracy achieved was 81.75%.

However, the study shows room for improvement where the model can be altered to suggest a combination of remedial actions. In addition, the work provides results for the early detection strategy of students in need of assistance. It provides a starting point and clear guidance to the application of ML based on naturally accumulating programming process data. During the source code combination, snapshot data recorded from students’ programming process, ML methods can detect high and low-performing students with high accuracy after the first week of an introductory programming course. They compare their results to the well-known methods for predicting students’ performance using source code snapshot data. This early information on students’ performance is beneficial from multiple viewpoints [

33,

34]. Instructors can target their guidance to struggling students early on and provide more challenging assignments for high-performing students [

35]. The limitation is that their solution is applicable for programming courses only.

A recent systematic review has been conducted in [

36], and results indicated that various ML techniques are used to understand and overcome the underlying challenges, predicting students at risk and students drop out prediction. Overall, this review achieved its objectives of enhancing the students’ performance by predicting students at risk and students drop out, highlighting the importance of using both static and dynamic data. However, only a few studies proposed remedial solutions to provide in-time feedback to students, instructors, and educators to address the problems.

3. Methodology

This section describes the dataset we have gathered for this study and the pre-processing activities we have conducted on the data to make it more appropriate to be handled by the data mining and ML applications and tools. We finally use the data exploratory analysis to study the correlation between the various attributes that could impact students’ performance.

3.1. Data Collection and Dataset Description

The data was collected from a programming course taught for undergraduate students at the College of Information Technology (CIT), United Arab Emirates University (UAEU). The students must take this course in order to accomplish their graduation requirements. Students from other colleges may take the course as a part of their academic study plans mainly as a free elective course. Due to the gender segregation policy in UAEU, each section is either offered for male or female students. The data represents the performance of the students in the introductory programming course for the academic periods 2016/2017 (Fall and Spring), 2017/2018 (Fall and Spring), and 2018/2019 (Fall and Spring). The original dataset was collected from comma-separated value (CSV) files (a file per section). Each file consists of a list of deidentified students’ records, a student per row.

3.2. Data Pre-Processing

Pre-processing took place on the data to bring it to a readable format by the ML techniques. All files are first unified in a structure to overcome any inconsistencies. As a few instructors teach programming course sections, there are some differences in files structure, e.g., the number of quizzes or homework components varies. To deal with this inconsistency, the maximum capacity of each assessment was identified, and all files were modified by creating additional columns with the missing checkpoints if there are any. The new columns are populated with the average of the corresponding assessments type. For example, the number of HWs varied between three and four in different files; therefore, the “HW4” column was added to all files where it was missing. Then, the averaged value of the previous three homework assignments was calculated and assigned to the new column “HW4”. The overall average of the coursework component, the final course marks, and the final grade are not affected. Other columns were created to hold some features that are necessary for the mining process. Those are the number of quizzes () given in the section, of the student, , section number (), the academic period (), and the .

Afterward, the files were integrated using Python script in one CSV file, and the marks were normalized employing min-max normalization (rescaling the features to the range between [0, 1]) employing following formula:

Finally, the missing values were treated with imputation methods and substituted with the averaged value of the same coursework components. Once the pre-processing step is completed, the normalized dataset is stored in the CSV format for further analysis.

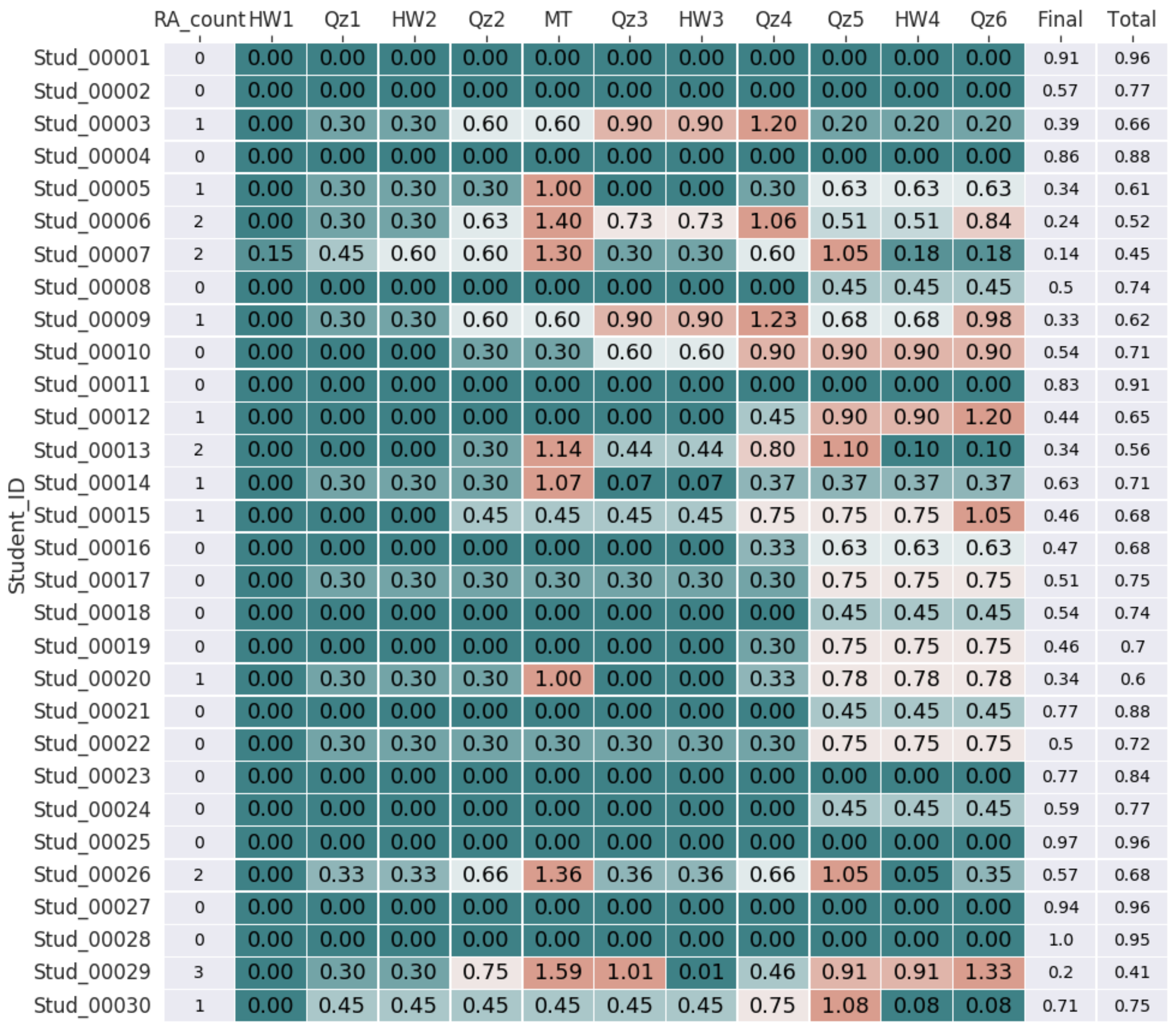

A typical data file structure is shown in

Table 1:

| - represents the name of the checkpoint predefined earlier |

| - is a grade of the jth student at the checkpoint |

| - is the maximum possible grade for the checkpoint |

| m | - corresponds to the number of students |

| n | - denotes the number of checkpoints in the course |

| - indices, |

Here, we have homework components (, ), quizzes (, ), mid-term (MT), final (Final) exam grades and total score (Total). Therefore, according to our data, . All checkpoints were used cumulatively up to the final exam as input variables to the model. This allows us to calculate an output variable risk flag (RF) each time when the new checkpoint values were fed to the proposed model.

3.3. Data Exploratory Analysis

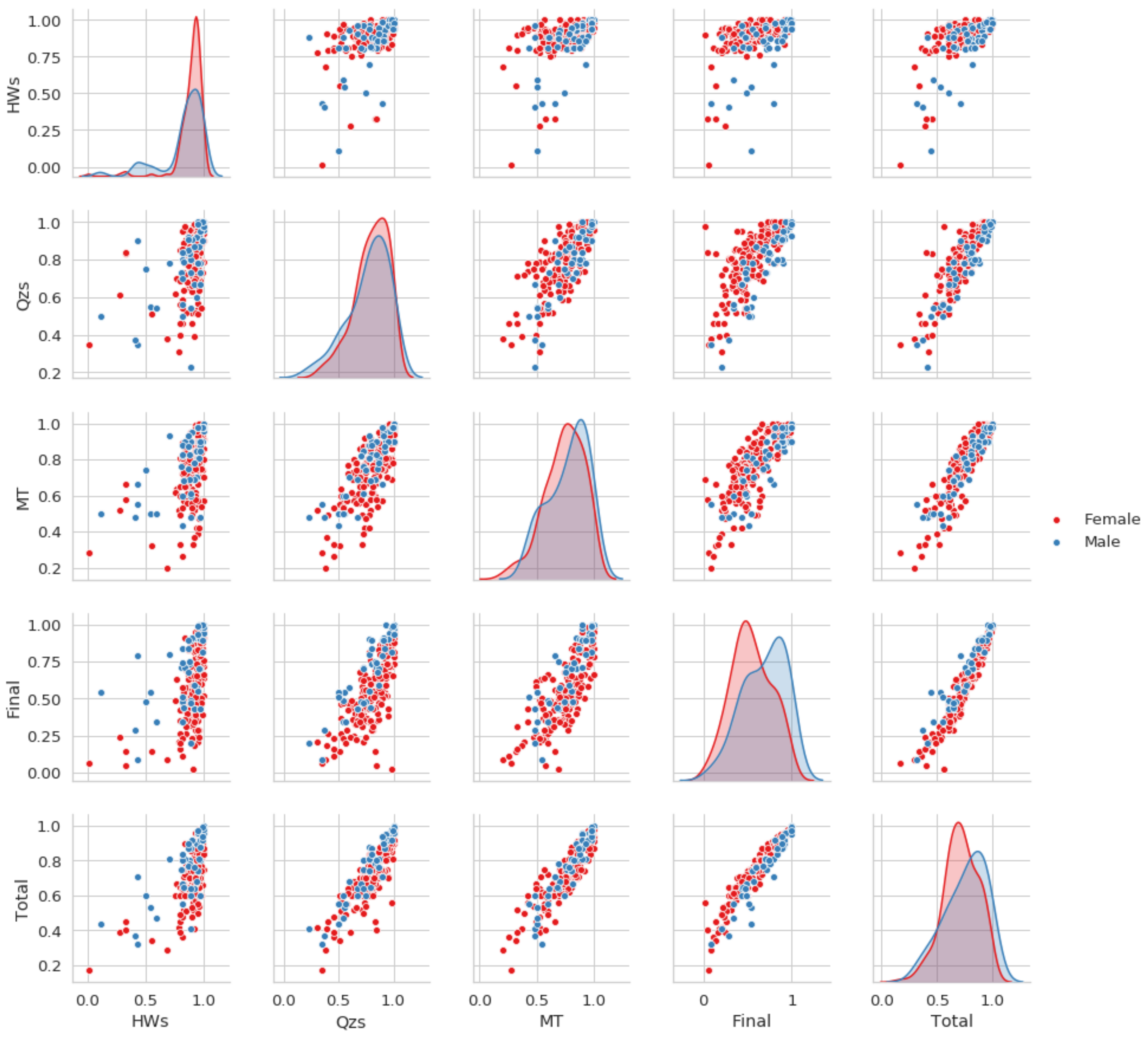

We started our exploratory analysis by looking at our data’s separability measures concerning the total grade. For this, we employed the Mann–Whitney U test as the features were non-normally distributed. From

Table 2 the performance of the students differs significantly among groups. The data are reported as median and interquartile range for the “Total” columns and median ± standard deviation values for the “High risk” and “Low risk” groups. There are no significant differences between performance groups in terms of gender (

).

To look at the predictive value of each feature in the data set, we evaluated the bi-variate correlation or a measure of the linear correlation between every two attributes in the data set utilizing Pearson correlation coefficients. The heat-map depicted in

Figure 1 indicates a positive correlation between all attributes and the final course grade, which was expected. The darker color on the heat-map corresponds to the higher correlation coefficient values. As expected, the Midterm (

), Quizzes (

), and Final grades have correlation values close to one with the Total score. However, the homework assignments (

) correlation values are significantly lower. It may indicate that the level of the homework tasks is not challenging enough for the students as well as the problems with the uniqueness of the answers, as almost all students outperform their results on

(mean = 87.7%, std = 14%) compared to other checkpoints, like

(mean = 79.3%, std = 16.4%),

(mean = 77.1%, std = 17.3%), and

(mean = 57.5%, std = 23.%), where percentage % stands for the performance level out of 100%. We used a scatter-plot matrix to explore further the distribution of a single attribute and relationships between two variables. As the total course grade is identified from four components, such as the average value of homework assignments, quizzes, mid-term exams, and final exam marks, we employed all mentioned features to investigate the joint distributions among them as well as univariate distributions.

Additionally, as normality is a prerequisite for many statistical parametric tests, we checked if our data is normally distributed employing the Shapiro–Wilk test. The test shows that the attributes are not normally distributed in the entire population (

p < 0.05). Presumably, male and female students have different performance levels concerning the type of assessment. To check this statement, we mapped plot aspects of male and female students to different colors.

Figure 2 shows that male students have slightly lower performance on

and

; however, they outperform female students on Mid-term and final exam scores. We must admit that the data are not balanced by gender (M/F 21.1%/78.9%), so the tendency may be changed. Then we employed the non-parametric version of ANOVA, the Kruskal–Wallis test to check if the population medians of gender groups are equal. This test can be used as it is applicable for the groups, which may have different sizes. The statistical test reveals significant differences between sexes (

) for the final exam grade.

According to the CIT practice, the significant level of student performance should be greater or equal to the cutoff value of 0.7. However, to efficiently identify and notify the instructor about students’ low performance, we suggest employing a heat-map technique and highlighting the low-performance level with different colors (see

Figure 3).

4. Customized Rule-Based Model to Identify At-Risk Students

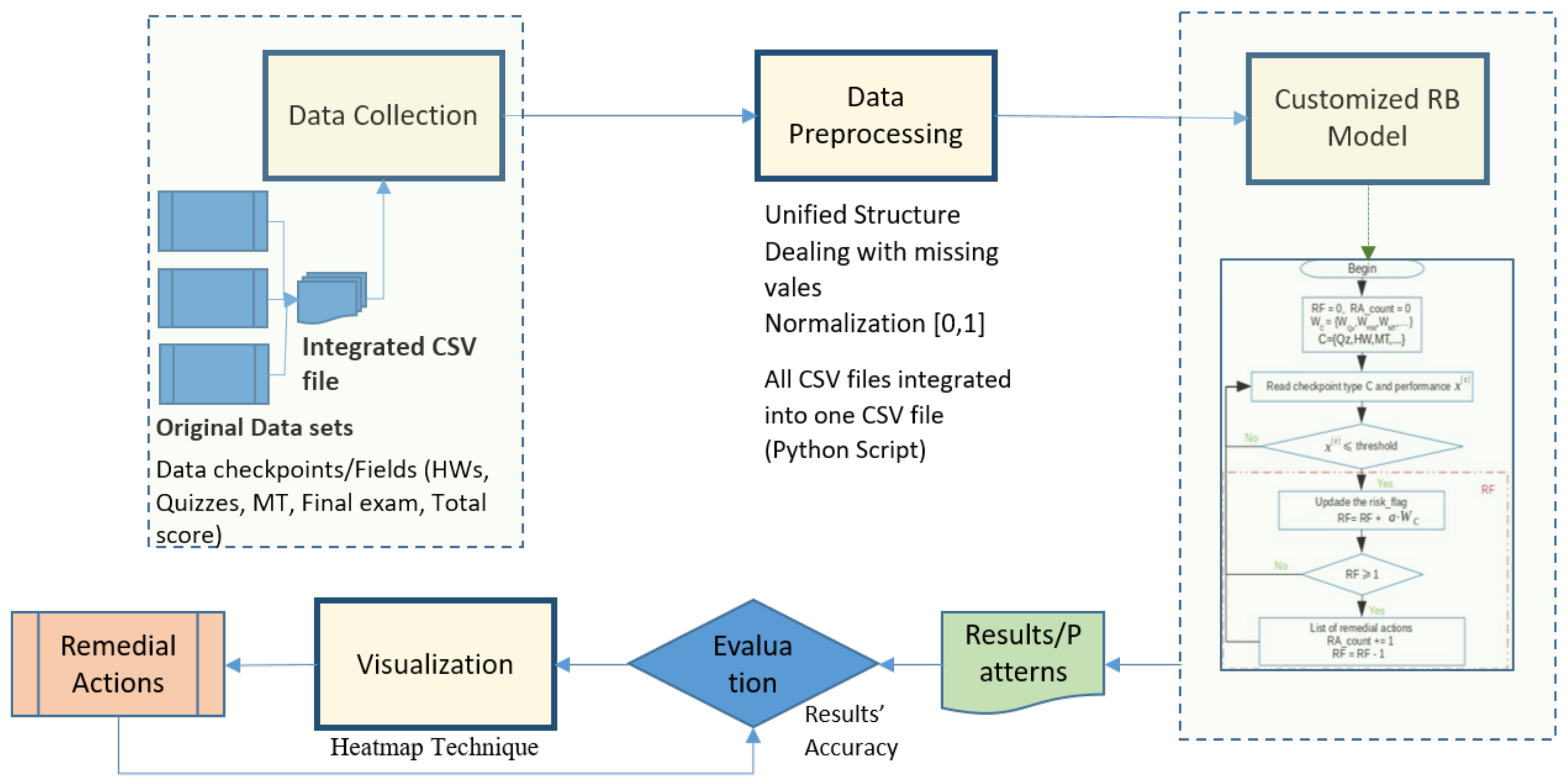

In

Figure 4 we illustrate the detailed flowchart of our proposed model. We start by data collection as a first phase, followed by data pre-processing to clean the data to make it ready to feed our customized model. After that, the output results will be evaluated and visualized through a heat-map. Finally, a decision to take remedial action will be taken.

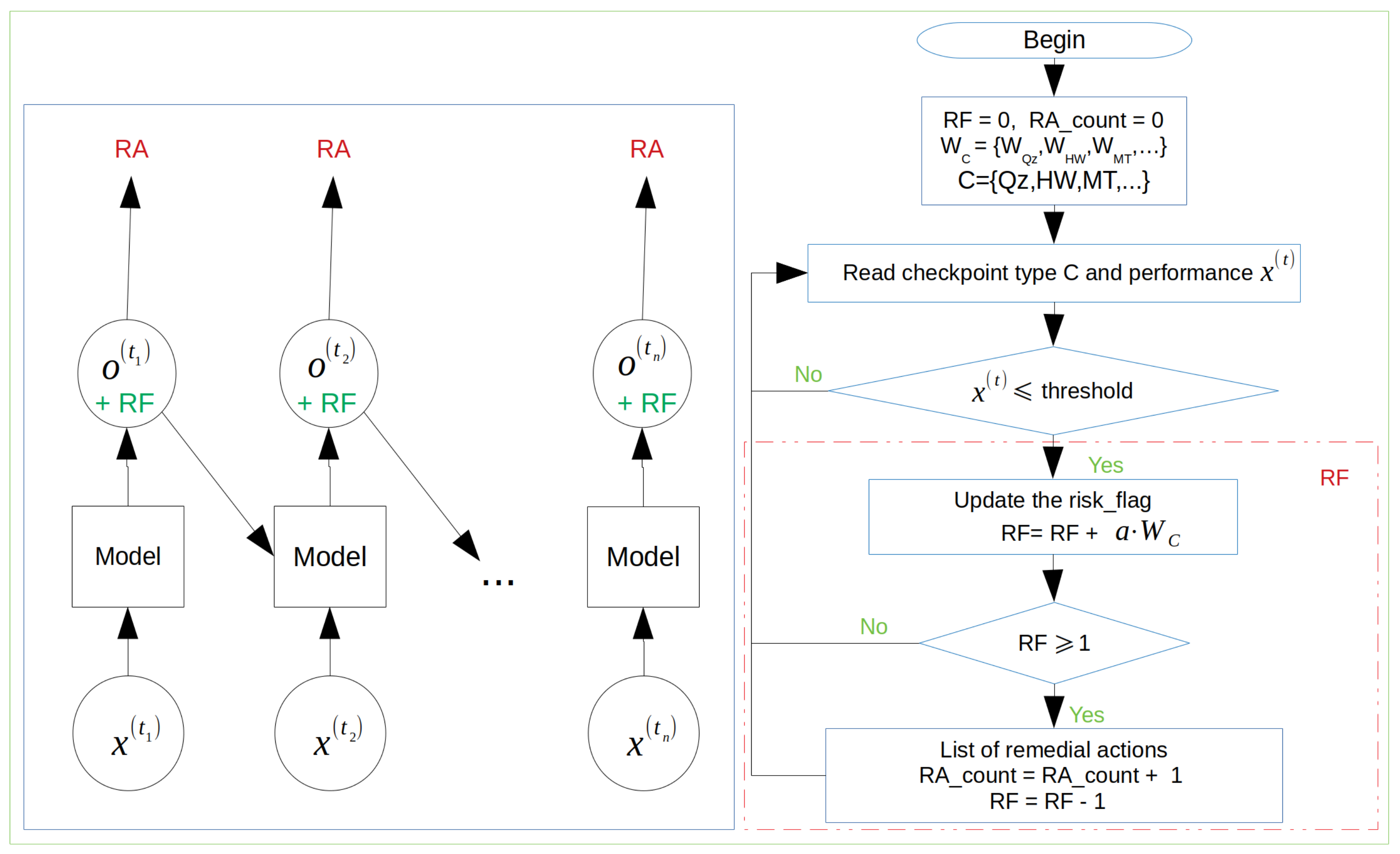

To identify under-performing students, we design a model that evaluates each student’s performance directly when assessment results are received.

Figure 5 illustrates the designed model, where the sequence of

n input vectors

fed to the model that classifies students into two groups: group at-risk or group not at-risk,

x is any entity from the set of Quizzes, Homework Assignments, Mid-Term Exam, and

t identifies the time when the assessment was conducted. The instructor can change the set of entities according to the course and the program requirements. The model’s output,

, is a rule-based outcome that analyses the value and type of the entity and returns the weighted value of the student being at-risk. A threshold is introduced to identify the at-risk student, which gives a cutoff level of risk and is set to 0.7.

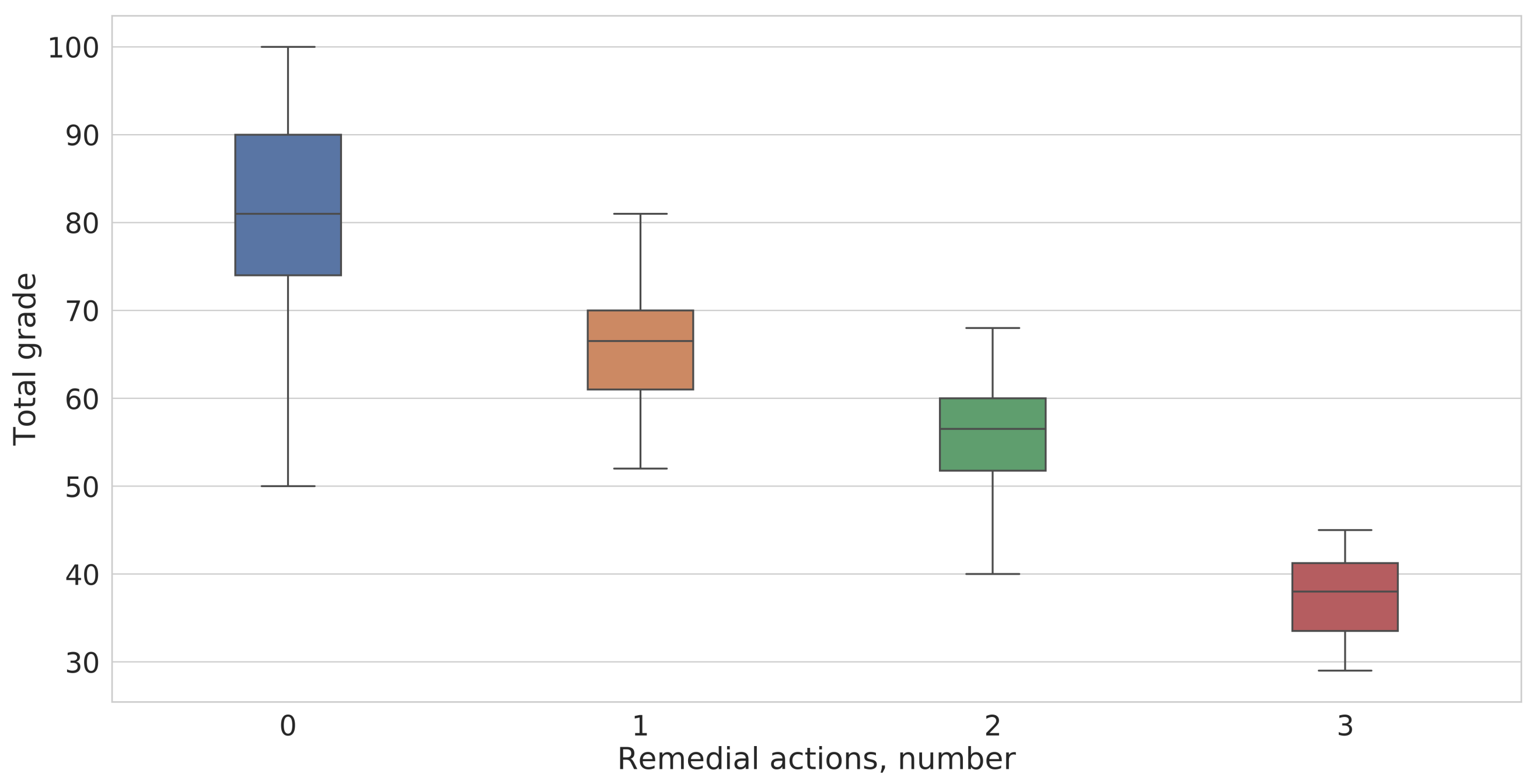

To identify when the remedial action takes place, a Risk Flag (

) indicator is introduced if there is any. Whenever the student’s performance drops below the

, the cumulative value of

is updated according to the following formula:

where

,

is a weight of the specific type of the checkpoint

and

is a weighted coefficient to increase the risk factor score, in case the performance of the student significantly drops. If

exceeds the value of 1, the list of remedial action (

) is invoked, and an appropriate

counter (

) is increased by 1, whereas 1 is deducted from the current

value (see formula (

3)).

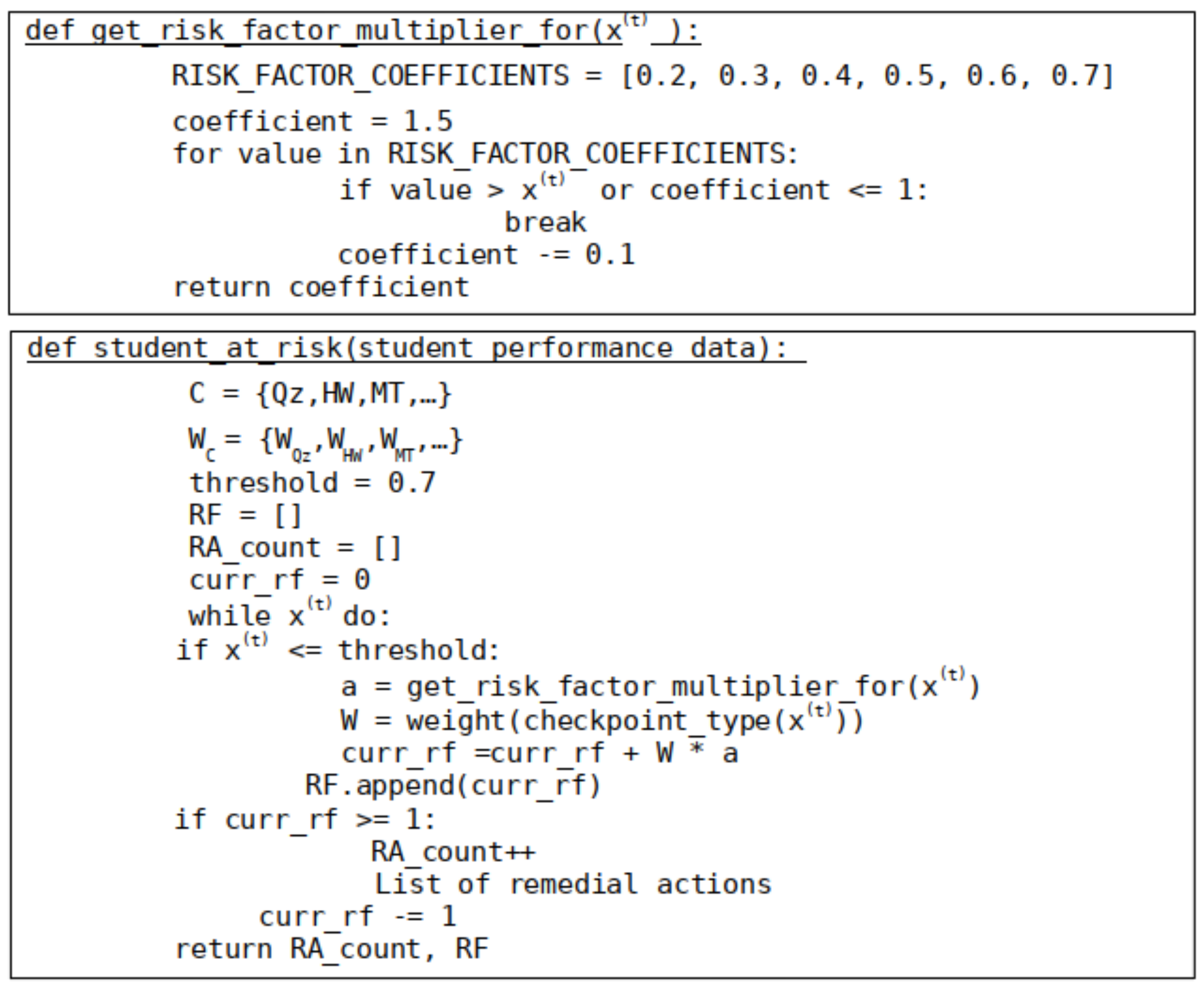

The pseudo-code of the proposed model is shown in

Figure 6. The model is designed to be fully customized by the instructor; therefore, checkpoints, weights, weighted coefficients, the list of remedial actions at the specific checkpoint, and the threshold values are used as model parameters and can be changed at the stage of initialization. The prototype of the proposed model is implemented in Python, where the instructor sets all customized parameters as JSON objects. The input of the model is the performance level of

m students in the CSV file with delimiter “,” as shown in

Table 1.

Visualization

To visualize the at-risk students, the color-map, introduced earlier, was employed. The green color indicates no issues with the student learning curve, whereas more orange color shows that the student may struggle to grasp learning outcomes and needs some assistance (

Figure 7). When the value of the

exceeds one, the list of remedial actions specified by the instructor is invoked and the value one is subtracted from the risk flag. This step is proposed to give the student some time to improve his/her marks denoting him/her again with the green color on the map. Furthermore, we examine how the risk flag is calculated with the upcoming checkpoints.

Figure 3 shows student performance values, and

Figure 7 reports the value calculated for each checkpoint of the risk flag.

Let us illustrate the process of building risk flag values. First, since our proposed model can be customized, the instructor sets weights for each checkpoint based on the importance of the input attribute for the final predictions. In this case “information gain” feature selection technique is used [

37] and we utilized retrieved weights as initialization values for vector

W. Thus, we obtained

,

,

. The vector of weighted coefficients was set to the values shown in

Table 3. The vector of weighted coefficients

a is between 1.0 to 1.5 according to the inverse dependency between the students’ performance and

value. The lower performance range corresponds to the higher value-weighted coefficients of

a.

With the method being proposed,

Table 4 illustrates

values calculated at every checkpoint for

, using formula (

2). For example, at checkpoint ”Qz4”, the student’s performance is equal to 0.5, meaning the student got 50% of the max grade for “Qz4”. According to the risk condition, all grades with values less than 70% are automatically considered potentially critical, and the

recalculation procedure is invoked. The

is calculated using the previous value of the

.

, where the value of the weighted coefficient is taken from

Table 3 and

is a weight of checkpoint quiz, set by the instructor at the initialization stage of the model. The

exceeded 1.0; therefore, the list of remedial actions is invoked, and the

counter (indicates the number of times, remedial actions were invoked) is incremented by one. To keep the visualization technique valid, we subtract one from the

value whenever it reaches one.