Contribution of Treated Sewage to Nutrients and PFAS in Rivers Within Australia’s Most Important Drinking Water Catchment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Water, Sediment, and STP Effluent Sampling

2.3. Water Quality Guideline Values for Drinking Water and Protection of Aquatic Biota

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Water Chemistry

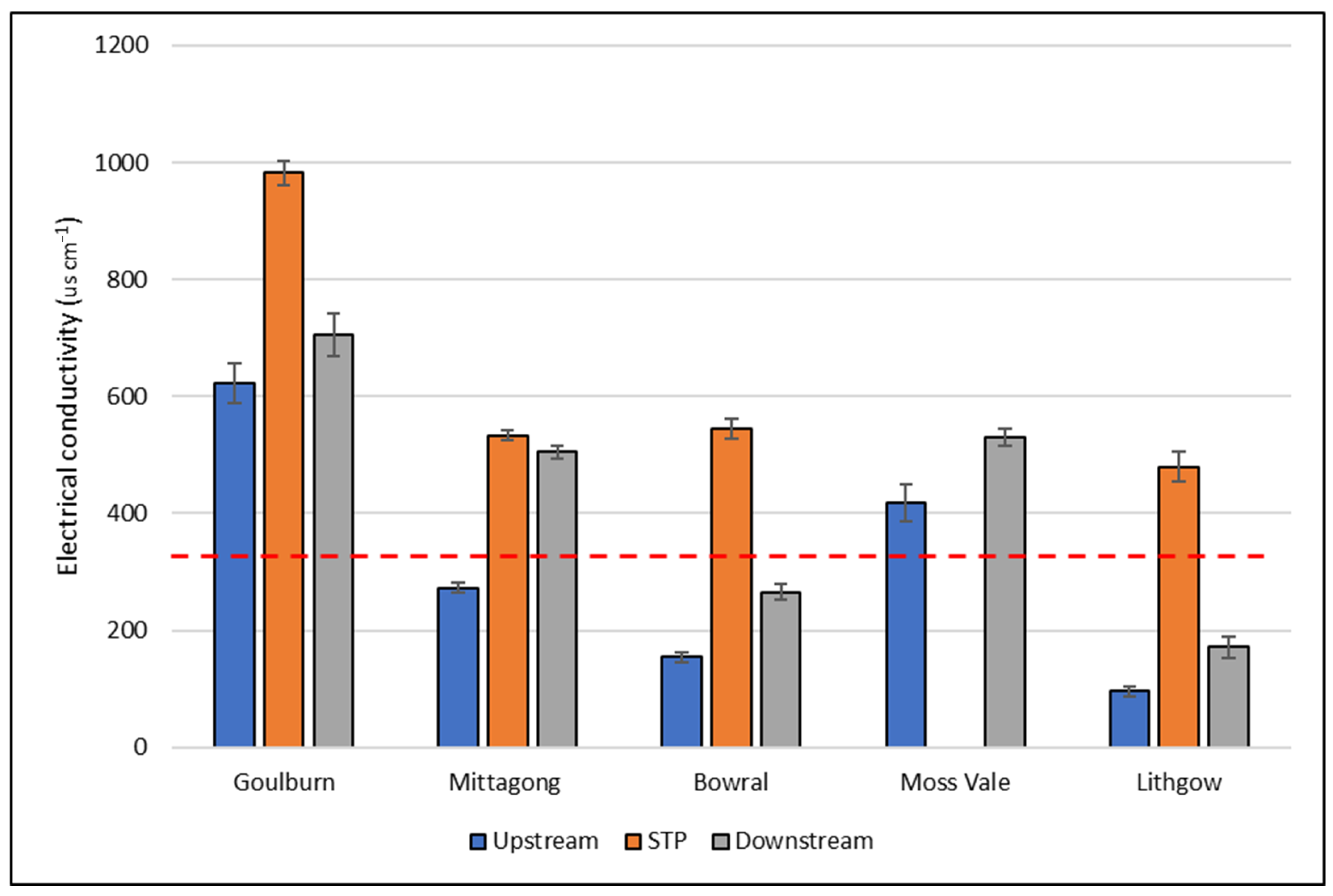

3.1.1. General Water Quality

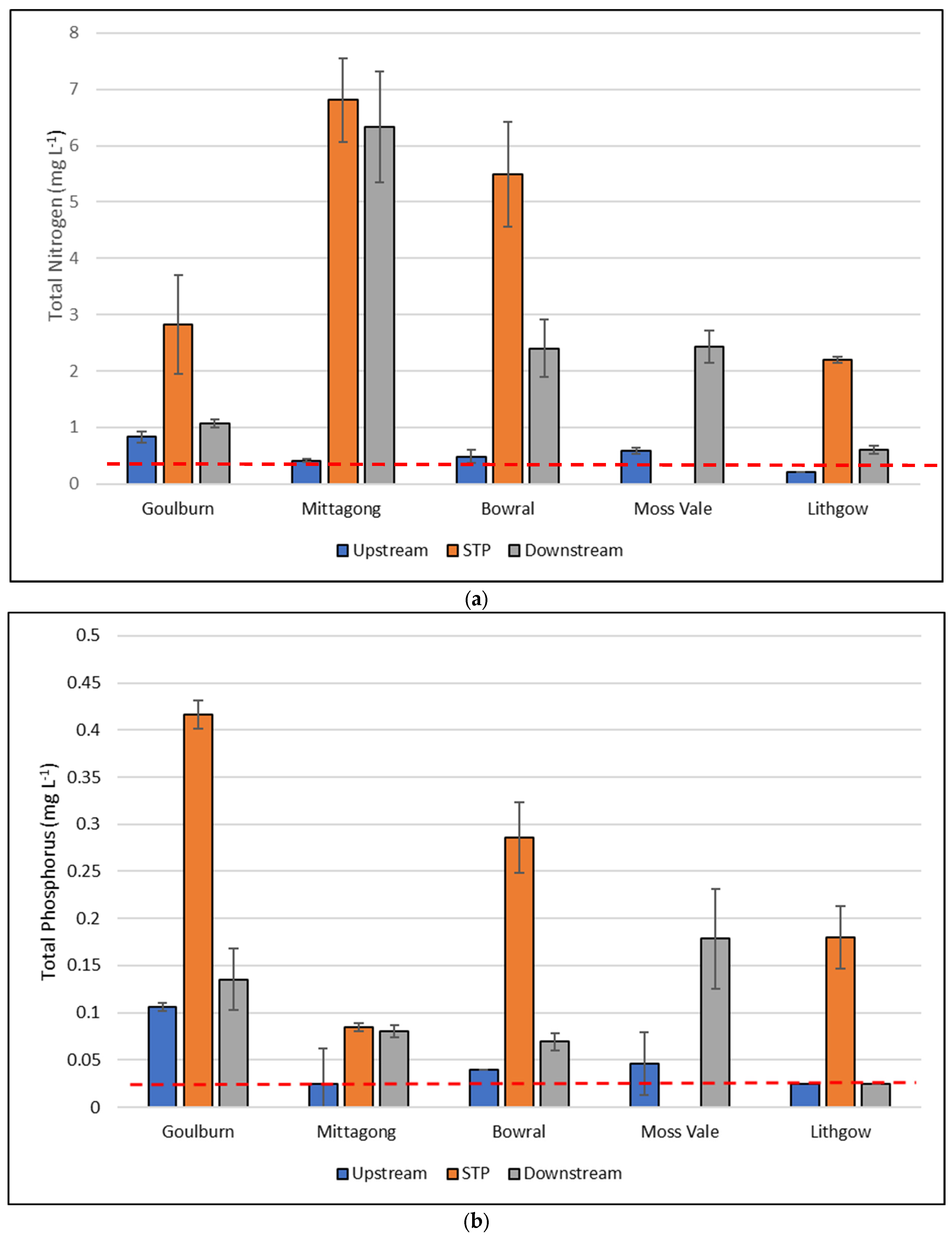

3.1.2. Nutrients

3.1.3. Metals

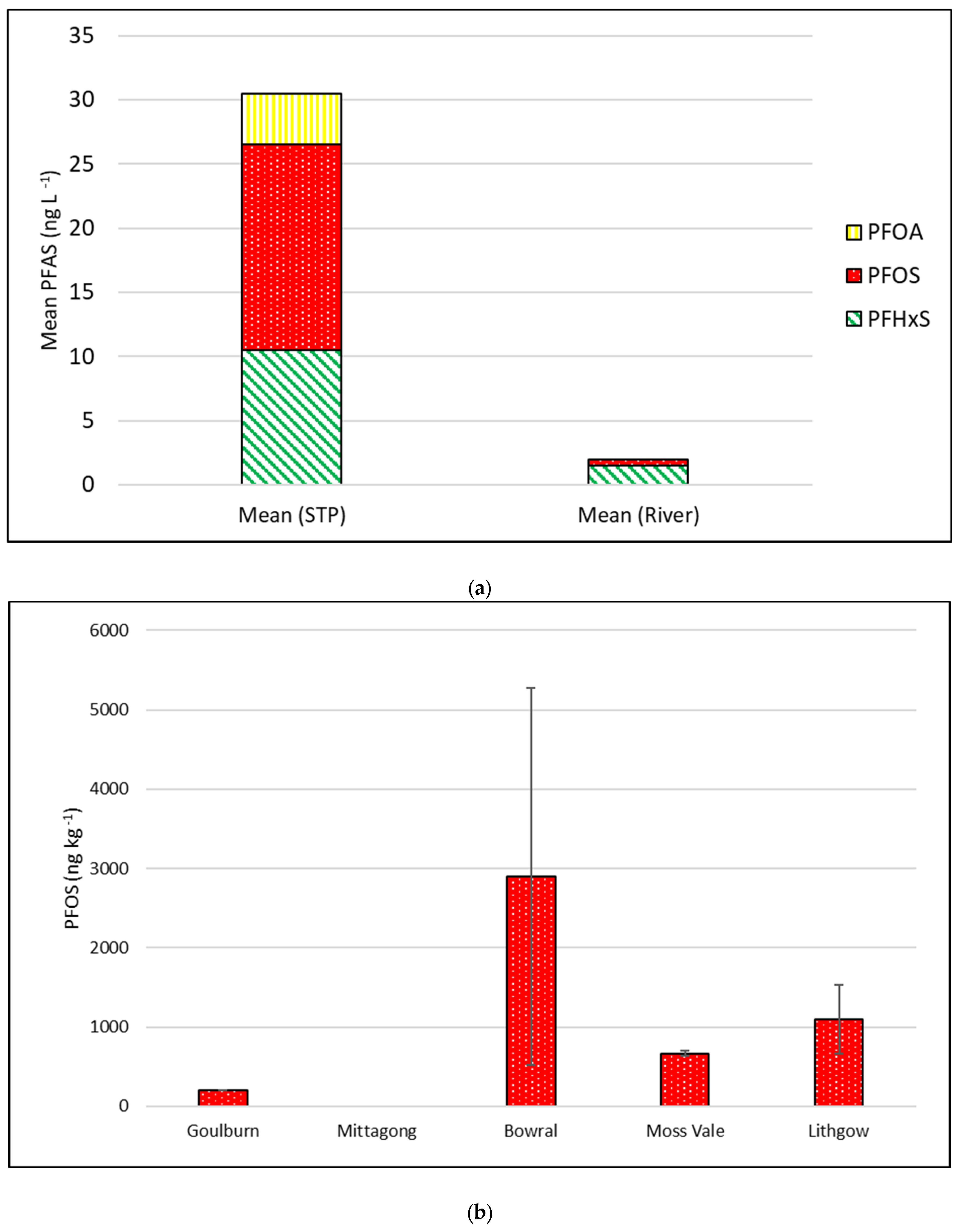

3.1.4. PFAS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EPL | Environmental Protection Licence |

| PFAS | perfluoroalkyl substances |

| PFOA | perfluorooctanoic acid |

| PFOS | perfluorooctane sulfonate |

| PFHxS | perfluorohexanesulfonic acid |

| STP | sewage treatment plant |

| WWTPs | wastewater treatment plants |

References

- UNSDG. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development, 2024. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Okoh, A.I.; Sibanda, T.; Gusha, S.S. Inadequately Treated Wastewater as a Source of Human Enteric Viruses in the Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 2620–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obaideen, K.; Shehata, N.; Sayed, E.T.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Mahmoud, M.S.; Olabi, A.G. The role of wastewater treatment in achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) and sustainability guideline. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckin, W. Evaluating the sanitary revolution: Tyohus and Typhoid in London 1851–1900. In Urban Disease and Mortality in Ninenteenth Century England; Wood, R., Woodward, J., Eds.; Batsford: London, UK, 1984; pp. 102–119. [Google Scholar]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Capodaglio, A.G.; Dialynas, E.G. Wastewater Management: From Ancient Greece to Modern Times and Future. Water 2023, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofrano, G.; Brown, J. Wastewater management through the ages: A history of mankind. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 5254–5264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, H.B.N. The Biology of Polluted Waters; Liverpool University Press: Liverpool, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Eutrophication of Waters. Monitoring, Assessment and Control; OECD: Paris, France, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvie, H.P.; Neal, C.; Withers, P.J.A. Sewage-effluent phosphorus: A greater risk to river eutrophication than agricultural phosphorus? Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 360, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullerjahn, G.S.; McKay, R.M.; Davis, T.W.; Baker, D.B.; Boyer, G.L.; D’Anglada, L.V.; Doucette, G.J.; Ho, J.C.; Irwin, E.G.; Kling, C.L.; et al. Global solutions to regional problems: Collecting global expertise to address the problem of harmful cyanobacterial blooms. A Lake Erie case study. Harmful Algae 2016, 54, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka-Krawczyk, P.; Żelazna-Wieczorek, J.; Skrobek, I.; Ziułkiewicz, M.; Adamski, M.; Kaminski, A.; Żmudzki, P. Persistent Cyanobacteria Blooms in Artificial Water Bodies-An Effect of Environmental Conditions or the Result of Anthropogenic Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.P.; Salmaso, N.; Paerl, H.W. Mitigating harmful cyanobacterial blooms: Strategies for control of nitrogen and phosphorus loads. Aquat. Ecol. 2016, 50, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, D.J.; Paerl, H.W.; Howarth, R.W.; Boesch, D.F.; Seitzinger, S.P.; Havens, K.E.; Lancelot, C.; Likens, G.E. Controlling eutrophication: Nitrogen and phosphorus. Science 2009, 323, 1014–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, L.; Baker, P. Major cyanobacterial bloom in the Barwon–Darling River, Australia, in 1991, and underlying limnological conditions. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1996, 47, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, G. Freshwater Algal Blooms and Their Control: Comparison of the European and Australian Experience. J. Environ. Manag. 1997, 51, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertessy, R.; Barma, D.; Baumgartner, L.; Mitrovic, S.; Sheldon, F.; Bond, N. Independent Assessment of the 2018–2019 Fish Deaths In the Lower Darling: Final Report. Australian Government, 2019. Available online: https://www.mdba.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/independent-assessment-2018-19-fish-deaths-interim-report.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Falconer, I.R. Problems caused by toxic blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) in drinking and recreational water. Environ. Toxicol. 1999, 14, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bláha, L.; Babica, P.; Maršálek, B. Toxins produced in cyanobacterial water blooms—Toxicity and risks. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2009, 2, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegraeff, G.M. Harmful algal blooms in the Australian region. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1992, 25, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, N. Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) exposure in dogs. Vet. Nurs. J. 2021, 12, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, D.; Coggan, T.L.; Robson, T.C.; Currell, M.; Clarke, B.O. Investigating recycled water use as a diffuse source of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) to groundwater in Melbourne, Australia. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coggan, T.L.; Moodie, D.; Kolobaric, A.; Szabo, D.; Shimeta, J.; Crosbie, N.D.; Lee, E.; Fernandes, M.; Clarke, B.O. An investigation into per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in nineteen Australian wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). Heliyon 2019, 5, e02316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappazzo, K.; Coffman, E.; Hines, E. Exposure to perfluorinated alkyl Substances and health outcomes in children: A systematic review of the epidemiologic literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, A.; Petaway, H.; Rivera-Diaz, V.; Day, A.; Colaianni, O.; Keramati, M. Per and polyfluoroalkyl substances scientific literature review: Water exposure, impact on human health, and implications for regulatory reform. Rev. Environ. Health 2021, 36, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet. Editorial: Forever chemicals: The persistent effects of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances on human health. eBioMedicine 2023, 95, 104806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem. The World’s Largest Collection of Freely Accessible Chemical Information. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Hu, X.C.; Andrews, D.Q.; Lindstrom, A.B.; Bruton, T.A.; Schaider, L.A.; Grandjean, P.; Lohmann, R.; Carignan, C.C.; Blum, A.; Balan, S.A.; et al. Detection of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in U.S. Drinking Water Linked to Industrial Sites, Military Fire Training Areas, and Wastewater Treatment Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2016, 3, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. Fact Sheet. PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation. 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-04/pfas-npdwr_fact-sheet_general_4.9.24v1.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- De Silva, A.O.; Armitage, J.M.; Bruton, T.A.; Dassuncao, C.; Heiger-Bernays, W.; Hu, X.C.; Kärrman, A.; Kelly, B.; Ng, C.; Robuck, A.; et al. PFAS Exposure Pathways for Hu-mans and Wildlife: A Synthesis of Current Knowledge and Key Gaps in Understanding. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 631–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesy, J.; Kannan, K. Global distribution of perfluoroctane sulfonate in wildlife. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 1339–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, K.; Newsted, J.; Halbrook, R.S.; Giesy, J.P. Perfluorooctanesulfonate and Related Fluorinated Hydrocarbons in Mink and River Otters from the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 2566–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, L.; Bundschuh, M. Fate and effects of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in the aquatic environment: A review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2014, 33, 1921–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, J.L.; Place, B.J. Perfluorinated alkyl acids in wildlife. In Toxicological Effects of Per-Fluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. Molecular and Integrative Toxicology; DeWitt, J.C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 127–150. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, D.; Bossi, R.; Carlsson, P.; Evans, M.; De Silva, A.; Halsall, C.; Rauert, C.; Herzke, D.; Hung, H.; Letcher, R.; et al. Levels and trends of poly and perfluoroalkyl substances in the Arctic environment: An update. Emerg. Contam. 2019, 5, 240–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foord, C.S.; Szabo, D.; Robb, K.; Clarke, B.O.; Nugegoda, D. Hepatic concentrations of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in dolphins from south-east Australia: Highest reported globally. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettoof, D.C.; Nguyen, T.V.; Richmond, W.R.; Nice, H.E.; Gagnon, M.M.; Beale, D.J. Bioaccumulation and metabolic impact of environmental PFAS residue on wild-caught urban wetland tiger snakes (Notechis scutatus). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 897, 165260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warwick, K.G.; Wright, I.A.; Whinfield, J.; Reynolds, J.K.; Ryan, M.M. First report of accumulation of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) in platypuses (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) in New South Wales, Australia. ESPR 2024, 31, 51037–51042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draft Toxicant Default Guideline Values for Aquatic Ecosystem Protection: Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) in Freshwater. In Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for Fresh and Marine Water Quality; Australian and New Zealand Governments and Australian State and Territory Governments: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2023. Available online: https://www.waterquality.gov.au/anz-guidelines/guideline-values/default/water-quality-toxicants/toxicants/draft-pfos-fresh-2023 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- The Sydney Water Incident July–September 1998. NSW Public Health Bull. 1998, 9, 91–94. Available online: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/phb/Documents/1998-8-9.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- McClellan, P. Sydney Water Inquiry. Fifth and Final Report. The Inquiry Into the Contamination of Sydney’s Water Supply, 1998. Available online: https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-07/Fifth-Report-Final-Report-Volume-2-December-1998.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Stein, P. The Great Sydney Water Crisis of 1998. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2000, 123, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydney Drinking Water Catchment Audit 2019–2022. Available online: https://www.waternsw.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/239344/Drinking-Water-Catchment-Audit-2022-Main-Report.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- ABC News. Sydney Dam Algae Grows to 26 km. 2007. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2007-09-03/sydney-dam-algae-grows-to-26km/658508 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Vigneswaran, B.; Faulkner, S.D. Cyanobacterial Bloom on Sydney’s Drinking Water Storage 2007: A Case Study-3. Nutrient Conditions in the Storage. In H2009: 32nd Hydrology and Water Resources Symposium, Newcastle: Adapting to Change; Engineers Australia: Barton, ACT, Australia, 2009; pp. 467–477. [Google Scholar]

- Kristiana, R.; Vilhena, L.C.; Begg, G.; Antenucci, J.P.; Imberger, J. The management of Lake Burragorang in a changing climate: The application of the Index of Sustainable Functionality. Lake Reserv. Manag. 2011, 27, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cook, M.; Spearritt, P. Water Forever: Warragamba and Wivenhoe Dams. Aust. Hist. Stud. 2021, 52, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aird, W.V. The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney 1788–1960 (Sydney: Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board (MWSDB), 1961. Available online: https://penrithcity.spydus.com/cgi-bin/spydus.exe/ENQ/WPAC/BIBENQ?SETLVL=&BRN=10419 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Sydney Catchment Authority. Dams of Greater Sydney and Surrounds: Warragamba. Available online: https://www.waternsw.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/4863/warragamba.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- WaterNSW. Special Areas Strategic Plan of Management 2015. Available online: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/research-and-publications/publications-search/special-areas-strategic-plan-of-management-2015 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- UNESCO. United Nations: Greater Blue Mountains Area. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/917/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- NSW Environment Protection Authority, Search for Environment Protection Licences. Available online: https://app.epa.nsw.gov.au/prpoeoapp/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Australian & New Zealand Guidelines for Fresh & Marine Water Quality. Available online: https://www.waterquality.gov.au/guidelines/anz-fresh-marine (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- HEPA. PFAS National Environmental Management Plan Version 2.0. 2020. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/protection/publications/pfas-nemp-2 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Grant, T.R. Platypus, 2007, 4th ed.; CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, VIC, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Academy of Science. Investigation of the Causes of Mass Fish Kills in the Menindee Region NSW Over the Summer of 2018–2019 Canberra, Australia: Australian Academy of Science, 2019. Available online: https://www.science.org.au/supporting-science/science-policy-and-sector-analysis/reports-and-publications/fish-kills-report (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Visit NSW: Lake Lyell Recreation Park. Available online: https://www.visitnsw.com/destinations/blue-mountains/lithgow-area/lithgow/attractions/lake-lyell-recreation-park (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Vilhena, L.C.; Hillmer, I. The role of climate change in the occurrence of algal blooms: Lake Burragorang, Australia. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2010, 55, 1188–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briefing. European Parliamentary Research Service. Urban Wastewater Treatment Updating EU Rules. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/739370/EPRS_BRI(2023)739370_EN.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Lee, T.; Speth, T.F.; Nadagouda, M.N. High-pressure membrane filtration processes for separation of Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 134023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Drinking Water Guidelines (2011)—Updated September 2022. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/australian-drinking-water-guidelines (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Final PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- NHMRC. Update on the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines (2024). Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/news-centre/nhmrc-update-australian-drinking-water-guidelines# (accessed on 11 February 2025).

| Lithgow | Goulburn | Mittagong | Moss Vale | Bowral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithgow Council | Goulburn-Mulwaree Council | Wingecarribee Shire Council | Wingecarribee Shire Council | Wingecarribee Shire Council | |

| Annual volume | 1000–5000 ML | 1000–s5000 ML | 1000–5000 ML | 219–1000 ML | 1000–5000 ML |

| EPL number | 236 | 1742 | 10362 | 1731 | 1749 |

| EPL 5-year review | 3 October 2024 | 11 May 2025 | 9 August 2024 | 15 January 2026 | 15 January 2026 |

| Coordinates of STP outfall | 33.4749° S 150.1351° W | 34.7370° S 149.7477° W | 34.4449° S 150.4382° W | 34.5420° S 150.3572° W | 34.4998° S 150.3867° W |

| Discharging to | Farmers Ck | Wollondilly River | Nattai River via Iron Mines Ck | Whites Ck | Wingecarribee River |

| Treatment system | Traditional trickling filtration and activated sludge treatment system | Membrane bioreactor and diffused aeration system | Intermittently decanted extended aeration (IDEA) and activated sludge | Intermittently decanted extended aeration (IDEA) and active sludge | Intermittently decanted extended aeration (IDEA) and activated sludge |

| TN | <10 mg L−1 (90%) <15 mg L−1 (100%) | <10 mg L−1 (90%) <15 mg L−1 (100%) | <10 mg L−1 (90%) | <10 mg L−1 (90%) | <7.5 mg L−1 (50%) <10 mg L−1 (90%) |

| TP | <0.5 mg L−1 (90%) <1 mg L−1 (100%) | <2 mg L−1 (90%) <3 mg L−1 (100%) | <0.3 mg L−1 (90%) | <0.5 mg L−1 (50%) <1 mg L−1 (90%) | <0.3 mg L−1 (50%) <0.5 mg L−1 (90%) |

| Ammonia | <2 mg L−1 (90%) <5 mg L−1 (100%) | <2 mg L−1 (90%) | <2 mg L−1 (90%) | <2 mg L−1 (90%) | <2 mg L−1 (90%) |

| * River flow (ML/day) | Farmers Creek (15.5 ML day−1) | Wollondilly River (11.5 ML day−1) | Nattai River (5.6 ML day−1) | No data available Whites Creek | Wingecarribee River (30.8 ML day−1) |

| Indicator (Units) | Benchmark Range |

|---|---|

| pH (pH units) | 6.5–8.0 |

| Chlorophyll a (µg L−1) | <5 |

| Dissolved oxygen (% saturation) | 90–110 |

| Total nitrogen (µg L−1) | <250 |

| Ammoniacal nitrogen (µg L−1) | <13 |

| Oxidised nitrogen (µg L−1) | <15 |

| Total phosphorus (µg L−1) | <20 |

| Filterable reactive phosphorus (µg L−1) | <15 |

| Turbidity (NTU) | <25 |

| Total aluminium (µg L−1) | <55 |

| Total manganese (µg L−1) | <1900 |

| Conductivity (μS cm−1) | <350 |

| Rivers/Streams Receiving STP Effluent | STP Effluent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US vs. DS (Mann–Whitney) | Upstream | Downstream | Outfall Discharge | ||||

| Water Quality Attribute | Significance | Range (Min.–Max.) | Mean | Range (Min.–Max.) | Mean | Range (Min.–Max.) | Mean |

| pH (pH units) | 0.006 | 7.0–9.4 | 8.3 | 7.1–9.4 | 8.0 | 7.1–9.6 | 8.0 |

| EC (μS cm−1) | <0.001 | 60.7–803.9 | 312.8 | 109.1–893 | 449.5 | 91–1109 | 645.2 |

| Water temp. (°C) | 0.062 | 11.9–25.2 | 17.9 | 12.1–27.5 | 19.3 | 14.7–24.4 | 19.7 |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 0.934 | 1.93–69.8 | 17.9 | 0.23–55.9 | 14.5 | 0.26–8.8 | 3.4 |

| Dissolved oxygen (% saturation) | 0.332 | 46.1–110 | 80.8 | 24.5–231.3 | 89.5 | 64.6–99 | 84.1 |

| Aluminium (µg L−1) | 0.004 | 50–1300 | 337.0 | 100–1100 | 479.7 | 20–1000 | 506.5 |

| Barium (µg L−1) | 0.016 | 10–81 | 35.4 | 3–56 | 24.7 | 3–20 | 10.3 |

| Copper (µg L−1) | 0.195 | <1–4 | 1.4 | <1–3 | 1.1 | <1–7 | 1.6 |

| Iron (µg L−1) | 0.003 | 260–1900 | 673.3 | 20–1800 | 421.6 | <1–460 | 122.2 |

| Lead (µg L−1) | 0.017 | <1–2 | 0.7 | <1–3 | 0.6 | <1 | <1 |

| Lithium (µg L−1) | 0.013 | <1–11 | 2.4 | <1–19 | 4.4 | 2–5 | 3.5 |

| Manganese (µg L−1) | 0.107 | 8–360 | 118.9 | 30–350 | 84.5 | 31–140 | 68.6 |

| Nickel (µg L−1) | <0.001 | <1–3 | 0.9 | <1–2 | 1.3 | <1–3 | 1.7 |

| Strontium (µg L−1) | 0.387 | 21–230 | 94.9 | 26–230 | 77.1 | 34–190 | 73.7 |

| Zinc (µg L−1) | 0.003 | 2–30 | 11.4 | 7–30 | 15.2 | 13–68 | 26.6 |

| Calcium (mg L−1) | 0.653 | 2–29 | 13.0 | 2–27 | 14.1 | 5.6–24 | 15.7 |

| Sodium (mg L−1) | 0.003 | 4–86 | 26.6 | 8–80 | 37.3 | 30–140 | 65.9 |

| Potassium (mg L−1) | <0.001 | 1–9.1 | 2.7 | 2–18 | 8.6 | 8.6–19 | 13.7 |

| Magnesium (mg L−1) | 0.182 | 0.6–22 | 8.3 | 0.9–23 | 11.2 | 2–21 | 10.4 |

| Bicarbonate (mg L−1) | 0.559 | 10–180 | 75.5 | 27–140 | 80.1 | 27–190 | 95.0 |

| Chloride (mg L−1) | 0.104 | 4–140 | 41.8 | 6–130 | 54.7 | 20–150 | 57.9 |

| Sulfate (mg L−1) | <0.001 | 3–58 | 12.2 | 5–110 | 50.1 | 61–130 | 87.7 |

| Total nitrogen (µg L−1) | <0.001 | 200–1300 | 486 | 400–11,000 | 2822 | 1100–10,000 | 4682 |

| Nitrate (µg L−1) | <0.001 | <5–670 | 172.6 | 110–7400 | 2049 | 310–7700 | 3608 |

| Nitrite (µg L−1) | <0.001 | <5–52 | 7.1 | <5–310 | 46.4 | <5–790 | 108.6 |

| Ammonia (µg L−1) | 0.016 | <5–160 | 49.5 | <5–1100 | 150.3 | <5–1100 | 404 |

| Total phosphorus (µg L−1) | <0.001 | <5–90 | 41.3 | <5–400 | 102.6 | 70–500 | 233.8 |

| LOR | Waterway Below STP Min.–Max. (Mean) | % Samples Containing Substance | STP Effluent Min.–Max. (Mean) | % Samples Containing Substance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFHxS | ≥10 ng L−1 | <LOR −10 (1.5) | 15 | <LOR −30 (10.5) | 50 |

| PFOA | ≥10 ng L−1 | <LOR | 0 | <LOR −20 (4) | 35 |

| PFOS | ≥10 ng L−1 | <LOR −10 (0.5) | 5 | <LOR −40 (16) | 65 |

| PFAS | ≥10 ng L−1 | <LOR −10 (2.0) | 20 | <LOR −70 (29) | 65 |

| LOR | Sediment DS STP Min.–Max. (Mean) | % Samples Detected Substance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFHxS (sediment) | ≥10 ng kg−1 | <LOR −600 (35.3) | 5.9 |

| PFOA (sediment) | ≥10 ng kg−1 | <LOR −100 (11.8) | 11.8 |

| PFOS (sediment) | ≥10 ng kg−1 | <LOR −7600 (935.3) | 76.5 |

| PFAS (sediment) | ≥10 ng kg−1 | BD −8300 (988.2) | 76.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Warwick, K.G.; Ryan, M.M.; Nice, H.E.; Wright, I.A. Contribution of Treated Sewage to Nutrients and PFAS in Rivers Within Australia’s Most Important Drinking Water Catchment. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060182

Warwick KG, Ryan MM, Nice HE, Wright IA. Contribution of Treated Sewage to Nutrients and PFAS in Rivers Within Australia’s Most Important Drinking Water Catchment. Urban Science. 2025; 9(6):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060182

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarwick, Katherine G., Michelle M. Ryan, Helen E. Nice, and Ian A. Wright. 2025. "Contribution of Treated Sewage to Nutrients and PFAS in Rivers Within Australia’s Most Important Drinking Water Catchment" Urban Science 9, no. 6: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060182

APA StyleWarwick, K. G., Ryan, M. M., Nice, H. E., & Wright, I. A. (2025). Contribution of Treated Sewage to Nutrients and PFAS in Rivers Within Australia’s Most Important Drinking Water Catchment. Urban Science, 9(6), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060182