Abstract

The lack of proper integration of inclusive design, accessibility standards, and universal design principles into urban planning has resulted in public open spaces that exclude many individuals, particularly those with disabilities or other marginalized groups. Integrating these principles is essential to create environments that are accessible, equitable, and beneficial for all individuals, regardless of their abilities, backgrounds, or socioeconomic status. To address this gap, this study analyzes existing research on universal design and accessibility standards to identify challenges and opportunities in the design of inclusive public open spaces. This systematic review seeks to critically explore how the application of universal design principles and accessibility standards supports the creation of inclusive public open spaces. Although universal design focuses on physical accessibility, inclusion in public spaces entails a more complex web of spatial, social, and policy factors. This research systematically evaluates international literature to determine key gaps, best practices, and action-oriented policy and design recommendations. The scope is situated within the Global South, particularly India, to align with the paper’s geographical focus. The findings emphasize that robust enforcement structures, contextual adjustments, and global standards are crucial for the successful implementation of universal design and accessibility integrated with inclusive design. This integration must begin at the initial stages of the design process and be maintained throughout planning, construction, management, and operation. The study further highlights the importance of stakeholder involvement as a critical component at every stage of the design and implementation process. It underscores the need for tailored strategies for urban spaces that incorporate cultural, regional, and socioeconomic characteristics. Additionally, the study highlights the potential of technology and innovation, such as digital accessibility tools and smart city efforts, to improve inclusivity. Finally, the study proposes future research directions, including the impact of inclusive design on social cohesion, the challenges faced in rural and peripheral areas, and the role of modern technology in enhancing public open space design.

1. Introduction

Public open space is at the heart of city living, sustaining social interaction, culture, recreation, and community health [1]. It is essential city infrastructure, with the ability to provide equal opportunity to nature, recreation, and people interaction [2]. However, despite the increasing concern with universal design and accessibility, the majority of public space cannot be used by many user groups due to architectural barriers, adverse policy, and lack of implementation [3]. Guaranteeing public open spaces accessibility calls for proactive design to serve people with all abilities, including people with disabilities, elderly people, caregivers, and individuals with temporary impairment [4]. Public open spaces are essential for promoting social interaction, community health, and democratic engagement [5]. As cities grow, making these spaces accessible and inclusive becomes more important. Although there is increasing interest in universal design, most public spaces are inaccessible or underused by vulnerable groups. This problem is especially acute in the case of medium-sized Indian towns, where there is rapid urbanization, low planning capability, and socio-economic heterogeneity that poses additional challenges to inclusive public space planning. In order to frame this research, it is crucial to understand that public space inclusion goes beyond visual or physical accessibility. It includes spatial practices, sociocultural life of a place, economic affordability, the safety and vibrancy of the surrounding environment, and the types of activities facilitated. Thus, while universal design offers a grounding framework, it cannot by itself ensure inclusivity.

1.1. Understanding Universal Design in Public Open Spaces

Universal design has become a central principle for promoting accessibility through the development of an environment that can be used by everybody without the need for subsequent adjustments [6]. Unlike the conventional approach relying on accessibility compliance with laws subsequent to construction, universal design integrates accessibility in the early stages of the process [7]. Such a practice guarantees the accessibility of public open spaces with such amenities as barrier-free routes, tactile paving, sensory elements, and low-complexity wayfinding to promote ease of wayfinding for everyone [8]. Moreover, well-planned public spaces improve social inclusion by making it possible for various groups to engage in community life without segregation [9].

The concepts of universal design are not just physical and therefore surpass the notion of merely physical accessibility and involve cognitive and sensory considerations to provide a truly inclusive setting. Public buildings must include a range of seating options, proper lighting, visual contrast for wayfinding, and clear multilingual signage to further improve usability [10]. Research indicates that well-implemented universal design enhances not just accessibility but user experience overall, social integration, and mental health [11].

1.2. Challenges in Achieving Inclusive Public Open Spaces

Despite advancements in accessibility guidelines, urban spaces—like public parks, squares, and recreational areas—tend to be lacking in fundamental features that ensure full inclusiveness [12]. The majority of public spaces continue to cater to able-bodied individuals, neglecting the interests of marginalized groups, including the disabled, the elderly, and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities [13]. Evidence has shown that public areas in the majority of cities remain off-limits as a result of poor planning, poor finance, and poor regulatory compliance [14,15]. Retrofitting public spaces may be expensive and inefficient, underscoring the necessity of integrating universal design principles from the outset of urban planning and construction [16].

The essence of the inclusive design issue is the policy and practice gap. Norms such as that of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) focus on accessible environments, but system enforcement mechanisms have large divergences across jurisdictions [17]. Accessibility is an afterthought in most nations, while incorporation is mostly compliance-based and doesn’t necessarily address other concerns for inclusivity [18]. This provides spaces that are legally adequate but do not cater to the diverse needs of the users in every way.

1.3. Global Best Practices in Inclusive Public Space Design

Different cities of the world have successfully implemented public areas with creative urban planning schemes. Copenhagen urban parks, for instance, integrate universally accessible pathways, sensory parks, and user interfaces for persons with all ability types [19]. The New York City High Line is an example of an urban infrastructural development where spaces have been redesigned as priority is laid in accessibility via proper route design, seating provision, and directing pathways [20].

In Singapore, the ‘Barrier-Free Access’ initiative provides a program to ensure that public spaces, such as parks and waterfronts, are accessible through ramps, elevators, and tactile paving [21,22]. The success of these projects proves that incorporating universal design principles not only increases inclusivity but also enhances urban livability and economic vitality [23]. These case studies offer useful lessons for cities that aim to build more inclusive public open spaces, especially in fast-urbanizing regions where accessibility is usually an afterthought.

Although there is extensive research on universal design and accessibility guidelines, few studies target their application in public open spaces. Most of the current studies highlight building accessibility, with few addressing the complexities of outdoor settings, like parks, plazas, and streetscapes [24,25]. In addition, there is a requirement to think through how these principles are to be translated to diverse geographical, cultural, and socio-economic contexts, most especially in the fast-urbanizing parts of the Global South [26].

Inclusive environments should be friendly, comfortable, and engaging for all visitors, in addition to being physically barrier-free [27]. To construct inclusive spaces, it is essential to look beyond physical accessibility and consider building inclusive experiences in which the requirements of people with disabilities are effortlessly integrated into the design of the spaces and services offered. This research is built on a theoretical framework of inclusive public open space principles, universal design (UD), and accessibility requirements. The goal of universal design is to create an environment that is accessible to everyone without the need for adaptation [28]. It is designed and developed on inclusive design principles that take into account the needs of a broader spectrum of users, including the elderly, persons with disabilities, and those with other physical and mental limitations [29,30]. Public open spaces are important because they may address fundamental human needs while also providing unique interacting possibilities for city dwellers [31,32,33]. Numerous aspects of human functioning, including comfort, enjoyment, relaxation, and social stimulation, are addressed by these demands. Open places are physically bounded by borders and legal ownership [34]. It is undeniable that the kinds and accessibility of open spaces can greatly influence how included or excluded people from diverse socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds feel [35].

In most cities, particularly in the Global South, individuals with disabilities, older persons, children, and the economically poor frequently encounter multiple barriers to accessing public open spaces [36]. These are not only infrastructural shortcomings but also social stigma, policy loopholes, and the absence of participatory planning mechanisms. In addition, inclusion is also location-dependent, street-level accessible, ongoing practices, and the overall urban fabric, factors that cannot be resolved through design [37,38]. Universal design here means predominantly to include persons with physical or visual disabilities as well as individuals belonging to economically disadvantaged groups. In reference to policy, effective utilization of inclusive public space necessitates strategic design that speaks to policy inconsistency, increases the participation of citizens, and motivates the openness of the design to evolve from changing needs [39]. Examples of inconsistencies in policy include India’s Smart Cities Mission and the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, having disparate design mandates and tending to lack convergence.

This research systematically investigates universal design principles and accessibility standards in the context of public open spaces. The intention is to identify important gaps, review best practices internationally, and provide action-driven recommendations to develop more equitable cities. Following a review of case studies, policies, and empirical literature, the paper emphasizes the transformative potential of universal design in designing accessible, equitable, and socially resilient public spaces. The conclusions will also extend to the general debate about public open space inclusiveness, ensuring public open spaces not only meet their legal requirements but are also amiable, working, and inclusive for all.

1.4. Research Questions

This paper examines these intricacies by undertaking a systematic review of international literature on the implementation of universal design and accessibility principles in public open spaces. The review aims to achieve the following: (1) establish the fundamental components of inclusive design; (2) determine how universal design is implemented across various contexts; (3) determine policy and design inconsistencies that limit inclusivity; and (4) provide recommendations to make public spaces more inclusive.

Well-being and health advantages related to public open space, including enhanced mental well-being, social interaction, and physical activity, are well established [40]. They also promote social cohesion and community resilience. But their beneficial impacts are not felt in an equitable manner without the effective incorporation of inclusive design principles. It is imperative, then, to be aware of the theoretical and empirical aspects of inclusive design. The key research questions addressed in this study are as follows:

RQ1.

What are the current international standards and guidelines for accessibility in public open spaces, and how do they align with universal design principles?

RQ2.

How effectively have these standards been implemented in different urban contexts, particularly in developing countries?

RQ3.

What are the major challenges and barriers to creating inclusive public spaces, and how can these be overcome?

RQ4.

How can inclusive design principles be integrated into urban planning to promote social inclusion and sustainability, in line with the SDGs?

1.5. Literature Review

Recent research on urban design emphasizes the necessity and benefits of public open spaces [41,42]. Whether they are used for exercise or just to spend time outside in the fresh air, they have health benefits. The benefits of improving overall health and fitness as well as fostering a sense of well-being are increasingly important considerations for the sustainability and operation of public open spaces, particularly in view of the rising incidence of obesity and heart disease brought on by sedentary city living [43,44]. Additionally, public open spaces contribute significantly to mental well-being, reducing stress levels and enhancing emotional resilience [45]. Studies suggest that people who have regular access to green and open spaces report higher life satisfaction and community belongingness [46]. In addition, it has been observed that having access to these open spaces is associated with positive outcomes, such as an enhancement of cognitive function, a reduction in the symptoms of both anxiety and depression, and a general improvement in overall happiness [47].

Research [48] has also further supported the mental health advantages of green urban infrastructure, observing that nature-based areas provide psychological restoration, particularly for socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, although inequality in access is still a significant concern.

Informal social gatherings and learning can also take place in open settings, and it is possible to run into people from other cultures and customs [49]. Additionally, they can support the development of tolerance and understanding, which come from interpersonal interaction rather than the derogatory stereotypes that are common in environments with only one culture. Socially speaking, public open spaces are defined as areas that provide for a variety of required and/or optional social activities [50]. Required activities include traveling to and from work, schools, hospitals, and shopping centers; optional activities include going to parks and recreational spaces where one can jog, walk, meditate, rest, or just unwind. Such activities are based on the available opportunities for involvement in the area, as well as its characteristics and attributes.

In public open spaces, residents’ needs can be satisfied by four different kinds of demands: possibilities for comfort, relaxation, passive involvement, active engagement, and discovery [51]. In public areas, comfort stands for the necessities of life—food, water, and shelter [52]. It is logical to anticipate that if the need for comfort is not addressed, other requirements will be unmet [53]. However, people may put up with significant discomforts like a bevy of bothersome insects or a lack of shade structures in order to enjoy and benefit from their time outside. A greater degree of ease, both physically and mentally, is referred to as relaxation [54]. The perceived tranquility of a space has more to do with its use than with its physical attributes. However, it is vital to realize that they are interdependent, as physical characteristics have a significant impact on the level of relaxation in a site. The third desire for open spaces is passive engagement, which can similarly induce feelings of calm. Active participation is a more immediate experience because it entails touching and connecting with others, whether they are strangers or know one another. The fifth reason individuals use public open spaces is to fulfill a need for discovery, which is a reflection of their desire for both joyful experiences and stimulation.

Researchers contend that such experiential requirements are frequently disregarded in utilitarian planning procedures, where emphasis is laid on infrastructure rather than people-centered design [55]. This criticism points to a continued disconnect between planning purpose and experiential realities.

Public open spaces should be designed with principles of inclusivity that ensure that diverse users, including those with disabilities, can engage in social interactions, physical activities, and cultural participation without barriers. Inclusive design strategies, such as the use of sensory elements for the visually impaired, wheelchair-accessible pathways, and age-friendly seating arrangements, enhance the usability of public spaces for all [56]. Additionally, the application of smart technologies, such as real-time wayfinding apps and AI-based accessibility assistance, can further improve the navigation and experience of differently abled individuals [26,57]. Moreover, studies highlight the role of participatory design in fostering inclusivity by involving community members in the planning and design process [58]. Engaging users in co-design activities helps identify barriers to accessibility and ensures that solutions are practical and user-centered.

However, researchers also observed that, in practice, universal design initiatives tend to fail because of insufficient user consultation and the absence of policy imperatives [59]. This underscores the need for institutional backing to translate inclusive ideals into actual spatial experience.

In addition, it is stressed that inclusive urban design should be context-specific, since universal models tend not to consider local socio-political dynamics [60]. Although significant progress has been achieved in the ideas of developing inclusive public open spaces and accessibility requirements, it has been discovered that there is a gap in the practical application of the theories. There is a need for an inclusive, sustainable design [61]. Globally, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) calls for accessible public spaces as a human right. Steinfeld [62] emphasizes that accessibility should not be viewed as a compensatory strategy but as a proactive approach for fostering social inclusion. This aligns with the goals of universal design, which aims to update the consciousness of designers who create the built environment by considering the diverse needs of all users.

However, achieving accessibility goals requires collaboration between governments, urban planners, and communities to develop policies that prioritize inclusive design [63]. There is also a need for enforcement mechanisms that ensure that inclusive design guidelines are followed from the conceptual stage of public space development to implementation and long-term management [40]. Additionally, addressing the needs of specific marginalized groups, such as women, children, and the elderly, through gender-sensitive planning and participatory design approaches, remains an important focus for future research. Research further suggests that inclusive urban design must incorporate climate resilience strategies, ensuring that public spaces remain accessible during extreme weather conditions and environmental disruptions [26].

In this regard, researchers [64] argued that adaptation of strategies for climate change has to be built into the urban planning standards to prevent further entrenching spatial exclusion in times of environmental disasters. However, most frameworks are reactive and not proactive in such ways. Inclusive design has physical, sensory, cognitive, social, and economic aspects. Inclusive design, according to the Center for Universal Design, should make it possible for individuals of all ages, genders, abilities, and socio-economic statuses to use the space safely, independently, and with dignity [65].

The primary objective of this investigation is to bridge these gaps by exploring best practices in inclusive public space design and proposing strategies for their effective implementation in urban and rural contexts. This literature review has highlighted the theoretical underpinnings, previous research, and critical gaps related to universal design, accessibility standards, and inclusive public open spaces. While much progress has been made, significant gaps remain in the implementation of accessibility standards, particularly in developing countries like India. The findings of this review constitute a vital platform for the evolution of a more harmonized and comprehensive framework for urban design, a framework that is purposefully designed to resonate with the goals of SDG 11 and the requirements of national policy, thereby enabling the creation of public open spaces that are truly inclusive and readily accessible for every citizen.

2. Methodology

2.1. Sources

The research has made use of a systematic review approach, as previously mentioned, and the databases “Scopus and Web of Science” are combed through in order to locate publications that may be incorporated into the review. These two databases contain a wide variety of scholarly works on a number of subjects, all of which were written by researchers from different parts of the world. Inclusion criteria focused on empirical studies and case analyses published in English between 2010 and 2023. As a consequence of this, these two databases are an ideal choice for compiling research publications. The next section provides a full explanation of the process that was followed in order to complete the final articles. The search string involved in the process is as follows:

Search String Set 1—(“accessibility standards”) AND (“public open spaces”).

Search String Set 2—(“universal design principles”) AND (“inclusive design”).

Search String Set 3—(“urban spaces”) AND (“social inclusion”).

The next part will detail the method that was used to pick the search results that were generated using the aforementioned keywords once those results have been generated.

2.2. Data Extraction and Synthesis

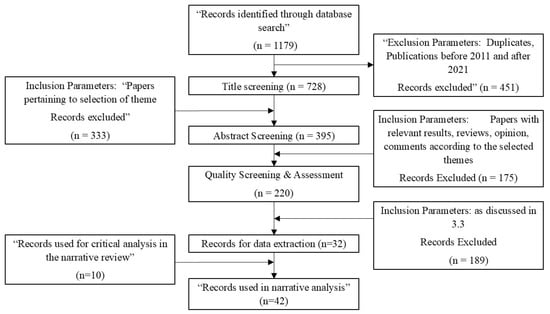

Use of a stringent technique to choose articles for final evaluation is one of the most critical criteria for successfully completing a systematic literature review. Other important criteria include the following: In the first step of the evaluation process, the articles are rated according to how relevant the titles are. After the connection between the title and the subject has been figured out, the abstract is given thorough consideration to see whether or not the overall work is up to par with the requirements. After doing an examination of the abstracts, the researchers chose the final publications to include in their study. After conducting extensive investigation, the most important topics that emerged from the final evaluation papers have been compiled into a list. In Figure 1, the PRISMA that was built below features a flowchart that outlines the entire process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (source: Author).

There was a systematic approach employed when synthesizing and extracting data to yield a systematic process of evaluating the existing literature on inclusive public open spaces. The selected research articles were screened, filtered, and analyzed in multiple rounds to identify the key themes, challenges, and best practices within inclusive urban design. Data extraction entailed systematically screening research articles that were retrieved from Scopus and Web of Science through clear inclusion and exclusion criteria. As shown in Figure 1, a preliminary number of 1179 articles was identified through database search based on the search queries outlined in the preceding section. Screening progressed through key steps such as title screening, abstract screening, and quality assessment. Articles were screened for relevance to accessibility, universal design, and inclusivity in public open space themes, resulting in the exclusion of 333 articles as they lacked thematic relevance. Abstracts of the final 846 papers were then sifted for relevance to the study purposes, excluding a further 451 papers for duplication, publication prior to 2011, or a non-public open space topic. A final quality check phase used a standardized proforma to ensure methodological consistency, yielding the final 32 research papers to be subjected to last-stage data extraction and thematic synthesis.

For a systematic synthesis of evidence, qualitative coding methods were applied to the uncovered literature. Articles were grouped in themes like universal design principles within urban areas, smart city endeavors and digital interconnection, people-centered planning of inclusive public places, socioeconomic as well as cultural aspects of the design of public spaces, sustainability and climate resiliency of inclusive public spaces, and policymaking for urban resilience. The PRISMA approach (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) was adopted to chart out inclusion and exclusion of studies so as to guarantee methodological consistency and reliability.

The extracted articles were examined based on a guided data extraction structure that recorded study titles and authors, geographical spread, major universal design principles, case study observations, and conclusions. The guided structure allowed comparative assessment of best practices worldwide and identification of regional differences in inclusive urban planning as well as intervention areas. After analyzing data that had been gathered, some significant observations were made in the process of synthesizing, such as policy enforcement loopholes, use of technological innovation towards accessibility, significance of urban planning for the marginalized communities, and consolidation of sustainability and resilience within public open spaces. Although international conventions like the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) promote accessibility in public places, there are weak mechanisms to enforce them in many developing countries. Further, research identified AI-based navigation aids, digital wayfinding technologies, and assistive technologies as upcoming trends in inclusive public space planning. Evidence also demonstrated that disability-inclusive and gender-sensitive urban planning and participatory governance frameworks are vital for increasing social inclusion. Climate-responsive design elements, such as shaded pedestrian corridors, water-sensitive urban planning, and green infrastructure, were proven to increase accessibility while promoting environmental sustainability.

Through synthesizing these findings, this research presents an overarching framework for the operationalization of universal design, smart city programs, and participatory planning to increase inclusiveness in public open spaces. This systematized literature synthesis not only reveals central challenges and opportunities for inclusive public open space design but also guides the following discussion on implementation strategies. The results enhance the understanding of the determinants of public space accessibility and usability, providing important insights for policymakers, urban planners, and designers who seek to design more inclusive environments.

2.3. Quality Parameters Used for Selection

In order to ensure that systematic review publications are of a high quality, Dyba & Dingsoyr [66] devised a questionnaire checklist [67]. The answers to these questions are graded based on how credible, rigorous, and relevant they are to the overall discussion. The items that were put forward for consideration are each given a score between one and zero based on how well they meet the aforementioned three quality standards. It is generally agreed that content with a score of four or higher is of a high enough standard to be considered for inclusion in the evaluation. You will find a table in the Supplementary Document with all of the different scores to help you better understand the method.

2.4. Threats to Validity of Research and Mitigations

Before carrying out a review, it is essential to perform an analysis of the construct as well as the external validity components. Dyba & Dingsoyr [66] created a quality assurance parameters checklist to mitigate any inequities or risks that can result from validity concerns in the papers [68]. The checklist is currently being utilized. Second, the best technique for lowering the risks related to authenticity fraud is the PRISMA method of article collection.

3. Results

This section is a descriptive analysis to provide an overview of the studies and standards covered in this review. A total of 32 research papers and review articles were carefully examined, representing a broad geographic distribution across different continents. The studies include a wide range of public open spaces, from urban parks and public plazas to beaches and retail markets, demonstrating the diverse nature of accessibility difficulties in different settings. Further, the analysis emphasizes the specific universal design principles used in this research, as well as the distinct contextual aspects that influence their conclusions. This comprehensive overview seeks to clarify the present status of research and practice in the subject of inclusive design, as well as identify major trends and gaps that require future examination. Table 1 is an account of the outcomes of the data extraction process that was carried out.

Table 1.

Summary of research papers based on primary data extracted from PRISMA method.

The review of the literature on universal design and accessibility in public spaces has identified key themes through the analysis of 21 research papers based on primary data and 11 review papers in Table 2. The key themes identified through the analysis are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Summary of review papers extracted from PRISMA method.

Table 3.

Key themes of the study.

Research from the United States and Turkey highlights inclusive design techniques; data from India indicate a lack of comprehensive strategies customized to local needs, exposing systemic challenges with public open space accessibility. The analysis emphasizes the significance of tailoring universal design principles to unique regional constraints, arguing for participative approaches that incorporate varied community perspectives.

There are a number of significant gaps in the adoption of universal design principles and accessibility requirements, especially in developing countries. According to Afacan [69], this study provided insight into the requirements, capabilities, and expectations of different user groups in a retail center [69]. Regardless of skill level, most participants claimed that current real-world applications fail to take into consideration the diverse expectations of users and that public spaces are designed with the average person in mind, leading to exclusion. The two most often recommended enhancements are easily understood signage and easy navigation. Signs’ visuals are difficult for people with visual impairments to read and too small for the elderly. However, inclusive design is not included in mainstream design in India. Because of this, a sizable portion of the populace—including the elderly and those with temporary, situational, and permanent disabilities—remains unable to enter numerous public locations. Although it is the responsibility of government organizations to create guidelines for making particular structures barrier-free, the ground rules do not include the use of accessible design in public open spaces. This study offers an inclusive design strategy that is accessible to a variety of people and communities in an effort to meet the necessity of inclusivity when creating public spaces [70,96,97]. Accessibility is widely regarded as an important aspect of architectural design practice. However, research indicates that the architectural design community has yet to fully embrace inclusive design. Inclusive design integrates accessibility principles, and its expanded definition takes into account crucial sociocultural and behavioral components such as physical, sensory, and cognitive needs [84,85]. Urban public spaces are essential to improving the quality of life for city dwellers [75]. Although ramps and accessible restrooms are the main physical adaptations that accessibility design now emphasizes, inclusive design is capable of much more. People with disabilities have a particular understanding of how the built environment is unfair, and inclusive design can be applied to all aspects of the city’s planning and urban development operations to highlight their voices and incorporate local viewpoints [98,99]. Urban planning, infrastructure, and building projects should have a vision for inclusive design that can be regularly followed in order to promote fairness and inclusion in the built environment [76].

An examination of the literature highlighted significant shortcomings in the application of accessibility guidelines and universal design principles in a variety of international contexts, with developing nations such as India facing particular difficulties. Very few studies were identified that focused on urban designing of open public places in India. Despite the increased understanding of the need for inclusive workplaces, research studies show significant differences in how these principles are applied, which are frequently influenced by local socioeconomic realities and cultural contexts. No studies were identified that focused on designing inclusive public open spaces in medium-sized towns or developing countries. This disparity reflects the lack of attention paid to rural communities, which are frequently disregarded in comparison to metropolitan centers in more developed countries. While big metropolitan cities may generate substantial research and investment to create accessible landscapes, medium-sized towns, particularly in developing countries, confront specific issues such as limited resources, fast urbanization, and insufficient planning frameworks.

4. Discussion

The concept of inclusiveness in public open spaces (POSs) has been widely discussed at the global level, yet its scientific application in Indian medium-sized towns remains a challenge. Public open spaces are unavoidable components of urban settlements and serve as places for recreation, social activity, and cultural expression [100]. They account for much in well-being, a sense of community, and improvement in living standards for the inhabitants. However, in the majority of the medium-sized towns, these spaces are typically underutilized, inadequately serviced, and lack the fundamental amenities to support various groups of users, including children, the elderly, and the disabled [101].

While universal design and access standards have been supported nationally and internationally, ground reality suggests scattered policies, poor enforcement, and a lack of awareness among planners, designers, and policymakers [102]. While inclusivity principles are defined in policy guidelines, their actual implementation on the ground is hindered by institutional barriers, underfunding, and a lack of participatory engagement at the community level [103]. This disparity between policy and implementation results in public open spaces that fail to accommodate the needs of every citizen, particularly marginalized groups. Moreover, haphazard development and accelerated urbanization have led to open spaces being encroached upon, reducing their availability and accessibility [104].

It is critical to fill this gap by determining and applying certain design interventions that focus on inclusivity while maintaining sustainability. This paper critically reviews the current guidelines and frameworks for inclusive public open spaces in India, determines the critical parameters for assessing inclusiveness, and situates their applicability to medium-sized towns with a population between 50,000 and 100,000. This research tries to offer effective strategies that will enhance the accessibility, safety, and usability of public open spaces in medium-sized towns through the study of case studies from both Indian and international perspectives, eventually culminating in more equitable and habitable urban space [104].

4.1. Key Themes of Inclusiveness in Public Open Spaces

A review of literature has identified key themes related to inclusiveness in public open spaces, which are integral to assessing and improving urban environments in medium-sized towns:

- 1.

- Universal Design Principles: The implementation of universal design ensures that public spaces cater to all individuals, regardless of ability. Key aspects include barrier-free movement, accessible seating, and inclusive recreational facilities. As shown in Table 4, many international case studies highlight that inclusive urban design not only benefits people with disabilities but also enhances the overall experience for all users.

Table 4. Remarks for universal design principles.

Table 4. Remarks for universal design principles.

- 2.

- Participatory Design Approaches: The involvement of local communities in the design and planning of public open spaces fosters inclusiveness. Participatory planning helps capture the diverse needs of urban residents, ensuring that public spaces reflect cultural, social, and functional aspirations. In Table 5, successful examples from international cities demonstrate that engaging marginalized groups in the design process results in more accessible and widely accepted urban spaces.

Table 5. Remarks for participatory design approaches.

Table 5. Remarks for participatory design approaches.

- 3.

- Assistive Technologies: The integration of technology into public space design, including mobile applications for accessibility mapping, real-time navigation assistance, and digital kiosks with multi-sensory features, improves the usability of urban spaces (Table 6). The Smart Cities Mission in India has explored these solutions in larger urban areas, but their adoption in medium-sized towns remains limited due to financial and technical constraints.

Table 6. Remarks for assistive technology.

Table 6. Remarks for assistive technology.

- 4.

- Accessibility and Social Inclusion: Ensuring that public open spaces are equitably distributed across different socioeconomic groups is crucial for inclusiveness. Table 7 helps in indicating, studies that highlight the need for spatial justice frameworks to evaluate the availability and usability of public spaces in underprivileged areas, preventing exclusion based on geography.

Table 7. Remarks for accessibility and social inclusion.

Table 7. Remarks for accessibility and social inclusion.

- 5.

- Urban Regeneration in Informal Areas: Revitalizing existing public spaces, particularly in informal settlements, can enhance accessibility and inclusiveness. Table 8 helps in marking, a participatory approach to urban regeneration, particularly in medium-sized towns, can help convert underutilized areas into vibrant community spaces that serve diverse populations.

Table 8. Remarks for urban regeneration in informal areas.

Table 8. Remarks for urban regeneration in informal areas.

- 6.

- Smart City Initiatives: The Smart Cities Mission emphasizes technology-driven accessibility solutions, including sensor-based navigation, automated transit information, and real-time monitoring of urban spaces for inclusiveness, as shown in Table 9. While these efforts have been concentrated in major cities, adapting similar frameworks in medium-sized towns can bridge gaps in urban accessibility.

Table 9. Remarks for smart city initiatives.

Table 9. Remarks for smart city initiatives.

- 7.

- Physical Barriers and Challenges in Urban Design: Many studies emphasize that hostile architecture—such as anti-homeless benches, gated communities, and restricted access to green spaces—negatively impacts inclusiveness. Overcoming these barriers requires a shift in design philosophy, promoting open, interactive, and universally accessible spaces. Table 10, comprehensively helps in marking studies on evaluation of inclusiveness of the public open spaces.

Table 10. Remarks for physical barriers and challenges in urban design.

Table 10. Remarks for physical barriers and challenges in urban design.

4.2. Existing Conditions of Guidelines for Inclusiveness in Public Open Spaces in India

India has introduced several policies and guidelines aimed at improving accessibility and inclusiveness in public spaces. Documents such as the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act (RPWD) 2016 [105], the Harmonized Guidelines and Space Standards for Barrier-Free Built Environment for Persons with Disabilities (2016) [106], and the National Urban Transport Policy (NUTP) emphasize accessible urban design [107]. The RPWD Act mandates the provision of barrier-free access in all public and private infrastructures, ensuring that persons with disabilities can access and navigate these spaces independently [108]. Similarly, the Harmonized Guidelines provide comprehensive recommendations for urban planners and architects to incorporate universal design principles in public buildings, streetscapes, and transit systems [109]. The NUTP focuses on integrating accessibility into public transport networks, emphasizing the need for pedestrian-friendly pathways and inclusive transit stations [110].

India has come up with numerous policies and guidelines to enhance inclusiveness and accessibility in public open spaces. Reports including the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act (RPWD) 2016, the Harmonized Guidelines and Space Standards for Barrier-Free Built Environment for Persons with Disabilities (2016), and the National Urban Transport Policy (NUTP) focus on accessible urban planning and design. The RPWD Act requires barrier-free access in public and private structures, allowing people with disabilities to independently approach and move about within these settings. Likewise, the Harmonized Guidelines offers general guidelines for architects and urban planners to include principles of universal design in public spaces, streetscapes, and mass transit. NUTP is all about incorporating accessibility into public transport systems, insisting on pedestrian-oriented routes and accessible transit stations.

Aside from these major laws, the National Policy on Senior Citizens (2011) also promotes the construction of age-friendly public spaces that are responsive to the mobility and safety concerns of older persons. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially Goal 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), also promote the need for inclusive urban design and planning with accessibility for everyone as a top priority [111]. Even with these forward-looking policies, their operationalization is mostly localized to the urban areas, while medium towns have limited infrastructural adjustments, weak enforcement systems, and unavailability of technical professionals to implement these guidelines effectively. Most ULBs of medium-sized towns are economically weak, so they are unable to accommodate inclusivity measures within their planning and development process [112].

In addition, although the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) focuses on creating green areas and parks with special facilities for children and elderly citizens, its effect on medium-sized towns is uneven because of implementation challenges, such as bureaucratic obstacles and a shortage of skilled labor. Likewise, India’s National Building Code (NBC) 2016 gives accessibility standards for buildings and urban areas, but enforcement in smaller urban settlements is poor, resulting in inequality in the quality of public open spaces.

A second challenge towards providing inclusiveness in public open spaces is insufficient urban mobility accessibility integration. DCRs lay out zoning and land-use plans but fail to cover inclusiveness facets like walkability routes, sensory navigation aspects, and accessibility of parks and play spaces equally [113]. Most towns have poorly designed pedestrian networks that compel individuals to walk through overpopulated and insecure spaces, deterring vulnerable groups, including the elderly, women, and children, from benefiting from public open spaces.

Encroachments and informal settlements further worsen the situation, usually limiting accessibility to planned public areas [114]. Parks and open areas in most instances are converted to commercial or infrastructural uses, making them less accessible for recreational and social purposes. Moreover, a failure to maintain them properly and inadequate management and security make vulnerable groups, such as women, children, and the disabled, shy away from effectively using these spaces.

The application of accessibility standards to medium-sized towns is also hindered by inadequate community participation. Public participation is important in helping to understand local needs and ensure that measures of inclusiveness are designed to respond to the particular demographic and cultural settings of individual towns [115]. Local governments, though, often exclude citizens from participation in planning and design, and as a result, end up with spaces that do not successfully respond to the varied needs of the population.

To counteract these challenges, it is crucial to establish a stronger enforcement mechanism, offer financial rewards for inclusive urban planning, and enhance coordination among local governments, private developers, and community groups [116]. Moreover, technological advancements, for example, GIS-based accessibility barrier mapping and mobile apps for reporting infrastructure shortcomings, can help monitor and enhance the inclusivity of public open spaces within medium-sized towns.

There is also a deficiency of integration between urban accessibility and mobility in public space. Pedestrianized areas and cycle-friendliness have been implemented in some cities, but such initiatives are still largely lacking in medium-sized towns. An integrated strategy must be developed to guarantee that public open space is accessible, well-connected, and designed for use by all abilities and backgrounds.

4.3. Parameters for Measuring Inclusiveness in Public Open Spaces

Table 11 helps to develop a comprehensive assessment framework for inclusiveness in public open spaces, key parameters must be identified. These parameters should account for social, physical, and functional dimensions of accessibility. Based on a review of the existing literature and urban policies, the following parameters emerge as crucial for evaluating the inclusiveness of POS:

Table 11.

Parameters from literature review for measuring inclusiveness in public open spaces.

- Physical Accessibility: Ensuring barrier-free movement through features such as ramps, tactile paths, curb cuts, and accessible restrooms. The presence of wide, obstacle-free pathways and transportation linkages that connect POS with residential and commercial areas is vital.

- Social and Cultural Inclusivity: Public spaces should cater to diverse social groups, including children, elderly populations, women, and persons with disabilities. The availability of shaded seating, play areas, and gender-friendly amenities (such as well-lit areas and separate toilets) significantly enhances inclusiveness.

- Wayfinding and Signage: Effective wayfinding elements, including multilingual signage, Braille instructions, and digital navigation tools, are critical in making POS accessible to individuals with visual or cognitive impairments.

- Safety and Security: Adequate lighting, surveillance systems, emergency response facilities, and clear sightlines are necessary for ensuring safety. Women’s safety, in particular, remains a significant concern in public spaces of Indian medium-sized towns.

- Participation and Community Engagement: The design and management of public spaces should involve community participation through participatory planning approaches. Inclusive POS must be designed with inputs from marginalized groups, ensuring that their specific needs are addressed.

- Multifunctionality and Adaptability: Spaces should be flexible to accommodate various activities, such as informal markets, cultural performances, recreational activities, and civic gatherings, catering to the diverse needs of the community.

- Environmental Sustainability: Inclusive design must align with ecological sustainability. Incorporating green infrastructure, water-sensitive urban design (WSUD), and climate-responsive landscaping enhances both accessibility and long-term usability of POS.

4.4. Considerations for Medium-Sized Towns in India

Medium-sized towns in India have distinct urban characteristics that differentiate them from large metropolitan centers. Their urban fabric consists of mixed-use developments, informal economies, and heritage precincts, which influence the functionality of public spaces. The following aspects must be considered while evaluating inclusiveness in POS for these towns:

- Urban Morphology and Layout: Many medium-sized towns follow an organic growth pattern with narrow streets and limited land availability. Implementing universal accessibility measures in these settings requires innovative design solutions, such as shared streets and pedestrian-prioritized zones.

- Economic Constraints: Unlike metropolitan cities, medium-sized towns have lower municipal revenues and limited funding allocations for urban improvement projects. Cost-effective solutions, such as community-driven maintenance and incremental design interventions, can help achieve inclusiveness without significant financial burdens.

- Heritage and Cultural Context: Several medium-sized towns in India have heritage cores that influence public space usage. Balancing the conservation of heritage assets with the need for accessibility enhancements presents unique challenges.

- Demographic Considerations: With a growing elderly population and increased migration from rural areas, POS must be designed to cater to a changing demographic landscape. Age-friendly infrastructure and culturally responsive designs should be prioritized.

- Integration with Urban Mobility: Last-mile connectivity to POS is often poor in medium-sized towns. Integrating inclusive public spaces with existing and planned transportation networks can improve accessibility for diverse users.

- Policy Integration and Governance: While national-level policies exist, their implementation at the town level is fragmented. Strengthening local governance through capacity-building programs, stakeholder collaborations, and digital monitoring mechanisms can improve inclusiveness outcomes.

4.5. Sustainability and the Future of Inclusive Public Open Spaces in Medium-Sized Towns

Sustainability in public open spaces is closely linked to inclusiveness. Well-designed inclusive spaces contribute to social sustainability by fostering community interactions and enhancing the quality of urban life. Additionally, integrating green infrastructure—such as urban forests, bioswales, and pervious pavements—ensures environmental resilience while enhancing accessibility.

Economic sustainability can be achieved through placemaking initiatives that attract footfall and support local businesses. Public–private partnerships (PPPs) can play a significant role in funding and maintaining inclusive public spaces in medium-sized towns. Furthermore, leveraging technology, such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for accessibility mapping and mobile applications for participatory urban design, can drive evidence-based policymaking.

4.6. Corresponding the Themes and Geographic Contexts

4.6.1. Conceptualizing Inclusive Design (RQ1)

Internationally, there is a non-uniform interpretation of what makes a place inclusive in public open spaces. Within Europe, inclusivity tends to focus on the technological and policy infrastructure for accessibility, as, for example, in the Nordic countries. Conversely, within Latin America and Southeast Asia, informal use habits and community involvement predominate the discussion. Whilst the majority of the research concentrates on physical design, less attention is paid to socio-economic inclusion and cultural appropriateness, specifically in African realities where spatial exclusion tends to mirror urban inequality.

4.6.2. Role of Universal Design in Accessibility and Inclusion (RQ2)

Universal design has emerged as one of the best approaches to widening accessibility, yet it is practiced differently from region to region. North American and European nations have strict accessibility codes, usually drawn from ADA and ISO guidelines. Implementation in Indian and other South Asian contexts is haphazard due to inadequate enforcement and awareness. The results identify that universal design is successful in catering to physical and sensory requirements but needs to be supplemented with inclusive governance, adaptive programming, and sensitivity to culture in order to effectively create inclusion.

4.6.3. Policy and Infrastructural Gaps (RQ3)

Policy fragmentation continues to be a major issue in India. While the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act specifies accessibility, city planning under the Smart Cities Mission disregards inclusive design. The discrepancy causes impediments in the implementation process at the local scales. In Africa, insufficient budget allocations for infrastructure and prioritizing business development cause bottlenecks for incorporating inclusive design. Studies from Latin America illustrate how models of decentralized urban governance have helped achieve more people-centric policies.

4.6.4. Efficient Structures and Mechanisms (RQ4)

Examples from Canada and Australia indicate the way nested frameworks—utilizing universal design, participatory planning, and recurrent audits—enhance inclusive urban development. In India, pilot initiatives such as the Bhubaneswar Smart City effort try to embed accessibility audits, albeit scale and persistence are problems. Medium cities (populations 50,000–100,000) generally lack the capacity to implement such structures, which are replaced with informal, ad hoc measures.

4.6.5. Medium-Sized Towns and Inclusion

This section deals with how medium-sized towns, especially in India, have problems with inclusive public space planning because of scarce technical capacity and dispersed governance. In contrast to large metropolitan cities, these towns do not have specialized planning departments and are highly dependent on state-level guidelines. Individuals with special needs, such as the elderly and the disabled, are more excluded because of the lack of tactile paving, accessible transport, or universal signage. These gaps can be overcome with the support of community-based programs and NGO partnerships, yet institutional support must be a long-term policy.

5. Conclusions

Inclusive design needs to be integrated throughout the whole design process, from conception to long-term management, so that public open space is accessible, fair, and valuable to everyone. Inclusivity in public open space design is not just a physical accessibility issue; it involves social, economic, and psychological considerations that are associated with the well-being of people. This study confirms the significance of universal design principles to create equal access for people to reduce physical and cognitive disabilities, increase social integration, and meet the needs of diverse inhabitants of urban areas. Despite as much international policy that requests accessible public environments, there are still loopholes in policy adoption, urban planning initiatives, and technology integration. The debate has shown that while inclusive public open space design efforts have been made worldwide, their execution tends to be fragmented and sporadic, especially in rapidly growing cities.

The study underscores that accessibility should not be viewed as a compensatory mechanism but as a fundamental aspect of urban development. Universal design principles go beyond regulatory compliance to encourage more understanding of human diversity in the built environment. Efficient enforcement mechanisms, contextual adaptation, and international standards are necessary to ensure the effective implementation of accessibility measures. Inclusive public open spaces must be the priority for governments and urban planners using active policies, special funding, and community-driven design approaches. The discussion concluded that public spaces require coordination of effort from many stakeholders, such as urban designers, architects, policymakers, community organizations, and technology developers, to design spaces that are accessible by a diverse group of users.

This paper emphasizes the necessity of a broader concept of inclusion that goes beyond physical accessibility. Universal design principles, when combined with participatory governance and just policies, can enable the development of public open spaces that are genuinely inclusive. Future studies must study local interpretations of inclusive approaches and experiment with them in varying urban contexts.

In addition to policy intervention, the integration of assistive technologies and smart city advancements also offers promising opportunities for enhancing accessibility, particularly in regions with a poor legacy infrastructure. Public–private partnerships need to be exploited to stimulate innovation in city accessibility so that future technologies benefit more inclusive public spaces. As already mentioned, urban design needs to address not just physical access but social inclusion as well to ensure that marginalized groups—like people with disabilities, children, and ethnic minorities—are addressed at all stages of design and development. Governments need to create specialized funding mechanisms and policy frameworks that incorporate smart solutions like AI-based wayfinding systems, automated assistive mobility devices, and real-time navigation systems into cities. By investing in such technological advancements, cities are able to make public space utilization more efficient and enhance mobility for people with diverse abilities.

The role played by public participation in inclusive space design cannot be overstated. Public participation contributes significantly to the development of urban spaces accountable to diverse social and cultural milieus, as well as to the identification of specific needs of specific populations. Participation planning practices that involve users at the decision-making level have proven to enhance accessibility and inclusiveness of public open spaces. Participatory design processes like co-design workshops and stakeholder engagement allow users to contribute their experience and in-situ knowledge in an effort to facilitate more context-sensitive urban interventions. Future research needs to investigate to what degree participatory design approaches can increase inclusiveness in public open space design and development and what their long-term social cohesion and resilience impacts are on cities.

Moreover, urban accessibility cannot be limited to metropolitan centers only. Research into inclusive design for rural and periphery contexts is also an important endeavor since accessibility problems within these contexts remain under-researched. Rural communities are often subject to unique infrastructural and spatial limitations that require specialized design strategies. As indicated in the discussion, comparative studies of comparing the success of universal design across different cultural, economic, and geographic settings can provide better data on global implementation best practices. Additional studies need to investigate the economic development, health, and overall quality of life gains achieved through inclusive public space, with specific regard to those vulnerable groups reliant upon them for social contact and daily living.

A further critical consideration is how inclusive public space can be made sustainable. Inasmuch as accessibility programs tend to be regarded as short-term measures, sustainable maintenance and adjustability of public space should not be overlooked in the long run. Future research should explore how sustainability and inclusivity can work together in urban design, understanding how green infrastructure, energy-saving solutions, and environmentally friendly materials can be woven into accessible public space. In addition, research must evaluate the effect of climate change on accessibility to public space, especially in areas that are vulnerable to extreme weather and environmental degradation.

Through the application of universal design, leveraging technological innovation, and good governance, public open spaces can be inclusive spaces. For this to be a reality, policymakers, designers, researchers, and communities will have to come together to design urban spaces that work for all people. Future policy interventions and research will have to prioritize accessibility, equity, and sustainability as key issues in bridging gaps and creating more resilient, more inclusive cities. Inclusive public open spaces in resource-poor urban environments need context-specific, operational approaches. This chapter provides a framework for effective application of universal design (UD) principles in small and medium towns, especially in India. The recommendations are organized under four pillars: policy design, financial models, capacity building, and technological enablement.

5.1. Policy Design Integration

Municipal development plans (MDPs) and smart city guidelines need to be updated to incorporate universal design principles as a compulsory assessment criterion. Inclusion standards need to include age-inclusive infrastructure, gender-sensitive spatial planning, and barrier-free mobility corridors. Local development control regulations can also include UD metrics in building and layout approvals.

5.2. Funding and Incentive Mechanisms

Considering the limited resources of medium-sized towns, public–private–community partnerships (PPCPs) may be utilized for co-creation of inclusive environments. The urban development departments at the state level may launch grant-based schemes for incentivizing cities that adopt inclusive design indicators. For instance, a “Model Inclusive Ward” fund could offer incremental fiscal incentives based on confirmed accessibility enhancement.

5.3. Capacity Building and Institutional Strengthening

Training modules on universal design and inclusive planning must be made available to urban local bodies (ULBs), architects, engineers, and municipal officers. These modules must be localized, translated into regional languages, and disseminated through hybrid modes—online webinars and in-field demonstration projects. Tie-ups with the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA) and local academic institutions can provide technical rigor.

5.4. Technology-Enabled Inclusion

In order to counter resource limitations, low-cost digital solutions must be implemented. These include the following:

Open-source participatory mapping systems (such as Maptionnaire or Ushahidi) for community feedback.

Mobile-accessibility audits, allowing citizens to report gaps in infrastructure.

Tactile GIS maps and voice navigation apps to assist individuals who are sensory impaired.

The findings of studies serve to reinforce again the necessity of planned city development so that urban form is not just determined by present-day accessibility requirements but also by adaptability, accessibility, and environmental sustainability in the future. By complementing the discourse on inclusive cities, this research contributes to a global movement towards the conceptualization of accessible, fair, and socially resilient cities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/urbansci9060181/s1, File S1: Prisma Data Sheet. Ref. [117] is cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and M.Y.; methodology, A.G.; software, A.G.; validation, A.G.; formal analysis, A.G.; investigation, A.G.; resources, A.G.; data curation, A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; writing—review and editing, A.G. and B.K.N.; visualization, A.G.; supervision, M.Y.; project administration, B.K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Clarkson, P.J.; Coleman, R. History of Inclusive Design in the UK. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 46, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, R.; Kelly, D.; Johnson, L.; Jong, U.D.; Watchorn, V. Housing at the fulcrum: A systems approach to uncovering built environment obstacles to city scale accessibility and inclusion. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2022, 37, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrie, R.; Hall, P. Inclusive Design—Designing and Developing Accessible Environments, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, K. Transport and social exclusion: Where are we now. Transp. Policy 2012, 20, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Razek, S.A.; Barakat, H.A.-R.; Ibrahim, S.M.S.Z. Universal and Inclusive Design in Public Open Spaces for Wellbeing-Oriented Cities: Design Strategies for the Case of Alexandria Public Beach. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2024, 19, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffitt, D.G.; Bartholomew, K.; Ewing, R.; Miller, H.J. Accessibility planning in American metropolitan areas: Are we there yet. Urban Stud. 2017, 56, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilola, M. Master of Culture and Arts Creativity and Arts in Social and Health Fields. Master’s Thesis, Metropolia University of Applied Sciences, Helsinki, Finland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Von Schönfeld, K.C.; Bertolini, L. Urban streets: Epitomes of planning challenges and opportunities at the interface of public space and mobility. Cities 2017, 68, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamraie, A. Designing Collective Access: A Feminist Disability Theory of Universal Design. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2013, 33, 78–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwarsson, S.; Stahl, A. Accessibility, usability and universal design—Positioning and definition of concepts describing person-environment relationships. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 25, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, H.; Hua, Y.; Jin, B.; Qiu, Z. Theoretical framework of life circles in Chinese small towns and the optimization of spatial layout for public service facilities based on residents’ distance sensitivity. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, R. ‘Out of Place’, ‘Knowing One’s Place’: Space, power and the exclusion of disabled people. Disabil. Soc. 1998, 13, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Kittow, R.J.; Keagan-Bull, R.; Giles, J.; Tuffrey-Wijne, I. ‘There’s a timebomb’: Planning for parental death and transitions in care for older people with intellectual disabilities and their families. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2023, 37, e13174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.J. Understanding the Challenges of Building an Inclusive Community. A Comparative Analysis of the Social Landscapes in Bø, Norway and Pune, India; University of South-Eastern Norway: Notodden, Norway, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wen, Y.; Li, Z. From blueprint to action: The transformation of the planning paradigm for desakota in China. Cities 2017, 60, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitas, A.; Avineri, E.; Parkhurst, G. Understanding the public acceptability of road pricing and the roles of older age, social norms, pro-social values and trust for urban policy-making: The case of Bristol. Cities 2018, 79, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys, J. Doing Disability Differently: An Alternative Handbook on Architecture, Dis/Ability and Designing for Everyday Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hersperger, A.M.; Grădinaru, S.; Oliveira, E.; Pagliarin, S.; Palka, G. Understanding strategic spatial planning to effectively guide development of urban regions. Cities 2019, 94, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; Walker, D.R.; Catalano, G.; Hoyler, M. Diversity and power in the world city network. Cities 2002, 19, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhang, Q. Assessing the public transport service to urban parks on the basis of spatial accessibility for citizens in the compact megacity of Shanghai, China. Urban Stud. 2017, 55, 1983–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, S. Manufacturing space: Hypergrowth and the Underwater City in Singapore. Cities 2015, 49, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakibamanesh, A.; Ghorbanian, M. Design Strategies for Dynamic and High-Quality City Centers. In Designing Responsive City Centers; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 113–154. [Google Scholar]

- Frías-López, E.; Queipo-de-Llano, J. Methodology for ‘reasonable adjustment’ characterisation in small establishments to meet accessibility requirements: A challenge for active ageing and inclusive cities. Case study of Madrid. Cities 2020, 103, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futcher, J.; Mills, G.; Emmanuel, R.; Korolija, I. Creating sustainable cities one building at a time: Towards an integrated urban design framework. Cities 2017, 66, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. World Cities Report 2020: The Value of Sustainable Urbanization; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Altıntepe, B.; Yüksel, M.; Altay, B. Cities for all: Co-design interventions on urban features by using inclusive. In Connectivity and Creativity in Times of Conflict; Academia Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 461–465. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinska-Dabkowska, K.M.; Bobkowska, K. Rethinking Sustainable Cities at Night: Paradigm Shifts in Urban Design and City Lighting. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaszák, G.; Kecskés, T. Universal Open Space Design to Inform Digital Technologies for a Disability-Inclusive Place-Making on the Example of Hungary. Smart Cities 2020, 3, 1293–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernawati, J.; Adhitama, M.S.; Alhad, M.A. The Changes in Public Open Space Usage and Perceptual Urban Design Qualities After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2024, 19, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, O.; Lennon, M.; Scott, M. Green space benefits for health and well-being: A life-course approach for urban planning, design and management. Cities 2017, 66, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzmann, K.R.; Wegener, M. Inventing Future Cities. disP—Plan. Rev. 2019, 55, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hajela, P. Dimensions of Public Spaces in Indian Market Places Feelings through Human Senses. Int. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2020, 14. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348740884_Dimensions_of_public_spaces (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Ercan, Z.M.A. New Generation Public Spaces How Inclusive Are They. In Proceedings of the Open Space: People Space Conference, Edinburgh, UK, 27–29 October 2004; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11511/79278 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Cao, J.; Kang, J. Social relationships and patterns of use in urban public spaces in China and the United Kingdom. Cities 2019, 93, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttazzoni, A.; Smith, L.; Lo, R.; Wray, A.; Gilliland, J.; Minaker, L. Urbanization, housing, and inclusive design for all? A community-based participatory research investigation of the health implications of high-rise environments for adolescents. Cities 2025, 160, 105809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzakis, T.; Alčiauskaitė, L.; König, A. The Needs and Requirements of People with Disabilities for Frequent Movement in Cities: Insights from Qualitative and Quantitative Data of the TRIPS Project. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G.; Wu, W. The role of stakeholders and their participation network in decision-making of urban renewal in China: The case of Chongqing. Cities 2019, 92, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talen, E. Urban Design for Planners: Tools, Techniques, and Strategies; Planetizen Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, I.Y.; Luo, J.; Chan, E.H. Spatial justice in public open space planning: Accessibility and inclusivity. Habitat Int. 2020, 97, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Ma, J.; Webster, C.J.; Chiaradia, A.J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X. Generative urban design: A systematic review on problem formulation, design generation, and decision-making. Prog. Plan. 2024, 180, 100795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbourne, P. Growing public spaces in the city: Community gardening and the making of new urban environments of publicness. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 2901–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Yiannakou, A. COVID-19 and urban planning: Built environment, health, and well-being in Greek cities before and during the pandemic. Cities 2022, 121, 103491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesura, A. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Elands, B.; Buijs, A. Social interactions in urban parks: Stimulating social cohesion. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kabisch, N.; Qureshi, S.; Haase, D. Human–environment interactions in urban green spaces—A systematic review of contemporary issues and prospects for future research. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, I.; Weitkamp, G.; Yamu, C. Public Spaces as Knowledgescapes: Understanding the Relationship between the Built Environment and Creative Encounters at Dutch University Campuses and Science Parks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enssle, F.; Kabisch, N. Urban green spaces for the social interaction, health and well-being of older people—An integrated view of urban ecosystem services and socio-environmental justice. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 109, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwah, A.A.; Li, W.; Alwah, M.A.; Shahrah, S. Developing a quantitative tool to measure the extent to which public spaces meet user needs. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 62, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bishawi, M.; Ghadban, S.; Jørgensen, K. Women’s behaviour in public spaces and the influence of privacy as a cultural value: The case of Nablus, Palestine. Urban Stud. 2015, 54, 1559–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.M.; Azzali, S. Examining attributes of urban open spaces in Doha. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.—Urban Des. Plan. 2015, 168, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, L.; Nguyen, Q.A.; Roettger, C.; Dixon, K.; Offenbächer, M.; Kohls, N.; Hirsch, J.; Sirois, F. Effectiveness of Progressive Muscle Relaxation, Deep Breathing, and Guided Imagery in Promoting Psychological and Physiological States of Relaxation. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 5924040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, A. Collective culture and urban public space. City 2008, 12, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space; Danish Architectural Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Salha, R.A.; Jawabrah, M.Q.; Badawy, U.I.; Jarada, A.; Alastal, A.I. Towards Smart, Sustainable, Accessible and Inclusive City for Persons with Disability by Taking into Account Checklists Tools. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2020, 12, 348–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W.H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, Conservation Foundation; Conservation Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, C.; Harold, G. DeafSpace and the principles of universal design. Disability and Rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 1350–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, S.C.; Simon, D.; Croese, S.; Nordqvist, J.; Oloko, M.; Sharma, T.; Buck, N.T.; Versace, I. Adapting the Sustainable Development Goals and the New Urban Agenda to the city level: Initial reflections from a comparative research project. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2019, 11, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A. Integrated Systems and Human-Centered Design Approach for Awareness, Early Diagnosis and Treatment Adherence of ADHD and ADD for Children of India; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld, E. The space of accessibility and universal design. In Rethinking Disability and Human Rights; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 100–118. [Google Scholar]