Dynamic Simulation Model for Urban Street Sweeping: Integrating Performance and Citizen Perception

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

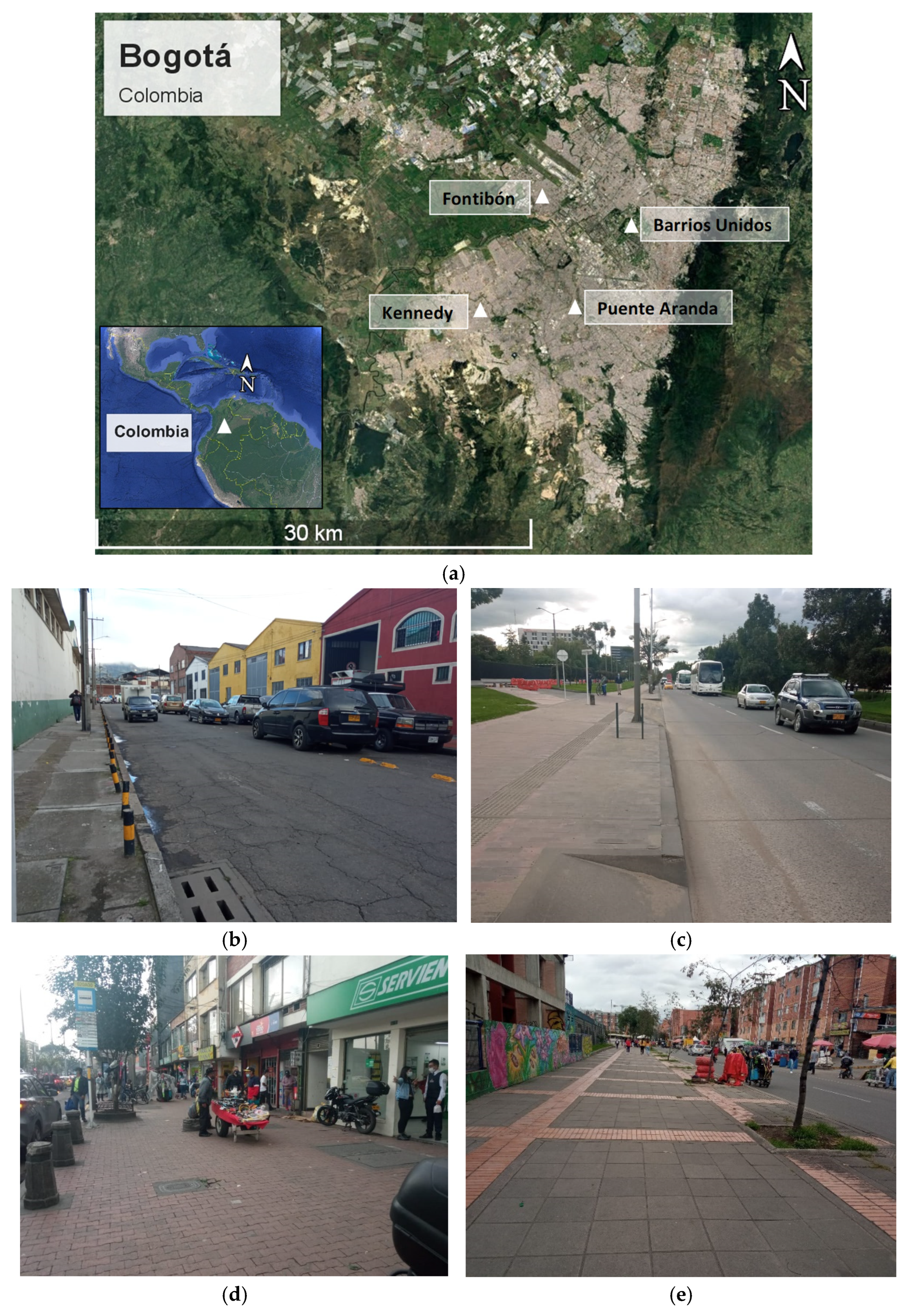

2.1. Description of Study Sites

2.2. Research Methodology

2.2.1. Phase 1: Detection of Street Sweeping and Citizen Perception Variables

2.2.2. Phase 2: Citizen Perception Survey

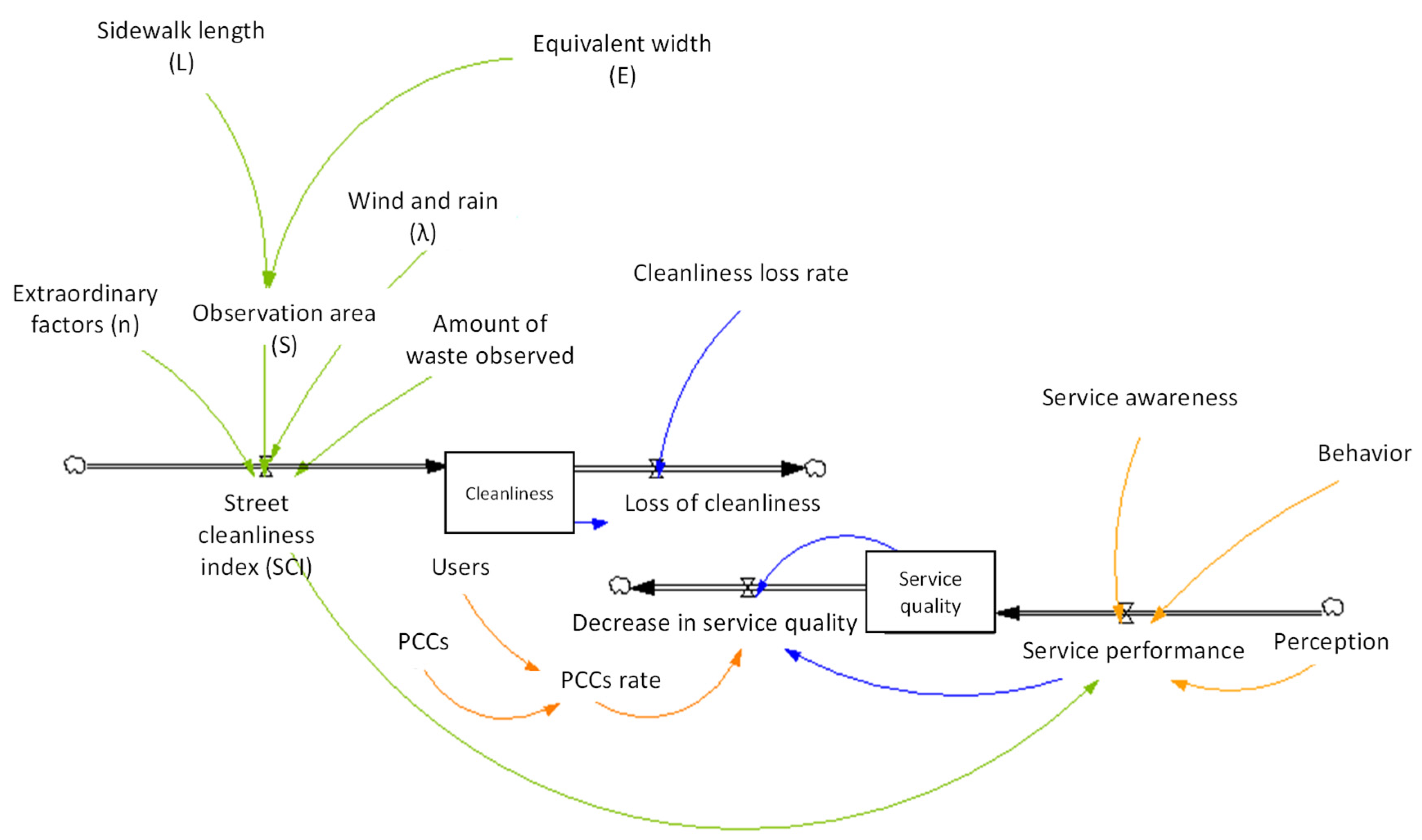

2.2.3. Phase 3: Dynamic Simulation Model

| No. | Type of Variable a | Variable | Units b | Calculation Method | Source of Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I | Actual width | m | Measured in the field | This study. Average width in each section observed |

| 2. | D | Equivalent width (E) | m | According to Sevilla et al. [11] | [11] |

| 3. | I | Sidewalk length (L) | m | Measured in the field | This study. Average lengths in each observed section |

| 4. | I | Extraordinary factors (n) | A | 1 = Absence of circumstances and 2 = Presence of circumstances | [11] |

| 5. | I | Wind and rain (λ) | A | Measured in the field | [11] |

| 6. | I | Amount of waste observed | A | Measured in the field | [11] |

| 7. | D | Street cleanliness index (SCI) | A | According to Sevilla et al. [11] | [11] |

| 8. | D | Loss of cleanliness | A | (−Service performance × cleanliness loss rate) + Cleanliness | Adapted from: [10,11,12,23] |

| 9. | D | Cleanliness | A | (SCI—cleanliness loss) × 0.10 | Adapted from: [10,11,12,23] |

| 10. | I | Cleanliness loss rate | A | 2.90 c | This study. Secondary information |

| 11. | D | Perception | % | Favorable public perception | This study. Applied survey |

| 12. | I | Service awareness | % | Correct knowledge about the street cleaning service | This study. Applied survey |

| 13. | I | Behavior | % | Appropriate behavior in the street cleaning service | This study. Applied survey |

| 14. | D | Service performance | A | SCI + perception + information—behavior | Adapted from: [10,11,12,23] |

| 15. | D | Service quality | A | Service performance—decrease in service quality | Adapted from: [10,11,12,23] |

| 16. | D | Decrease in service quality | A | (−Service performance × rate of decrease in quality) + Service quality | Adapted from: [10,11,12,23] |

| 17. | I | PCCs rate | A | PCCs/users | This study. Secondary information |

| 18. | I | PCCs | Number | Average PCCs for 2020 | This study. Secondary information |

| 19. | I | Users | Number | Average users for 2020 | This study. Secondary information |

2.2.4. Phase 4: Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

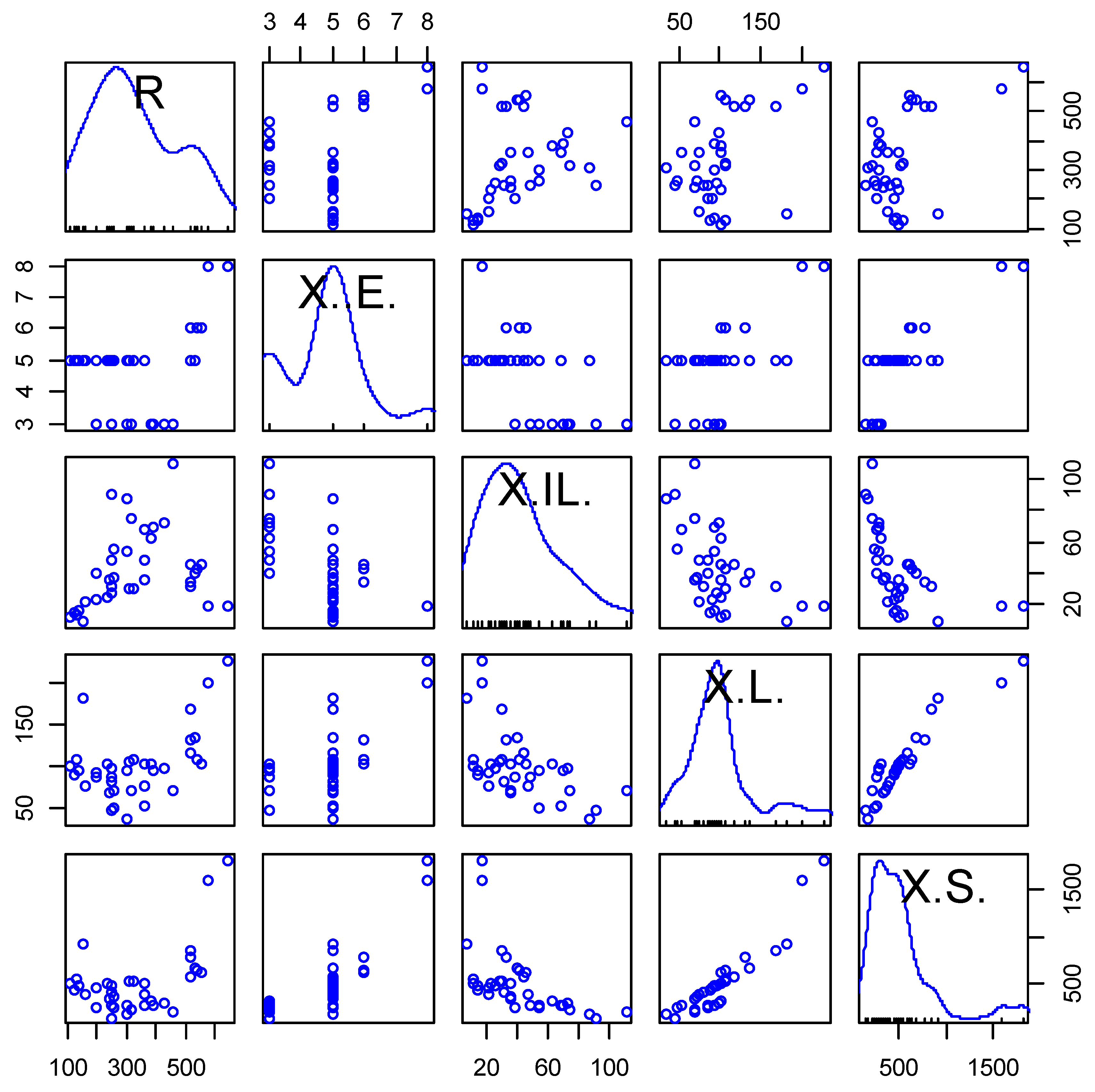

3.1. Variable Selection

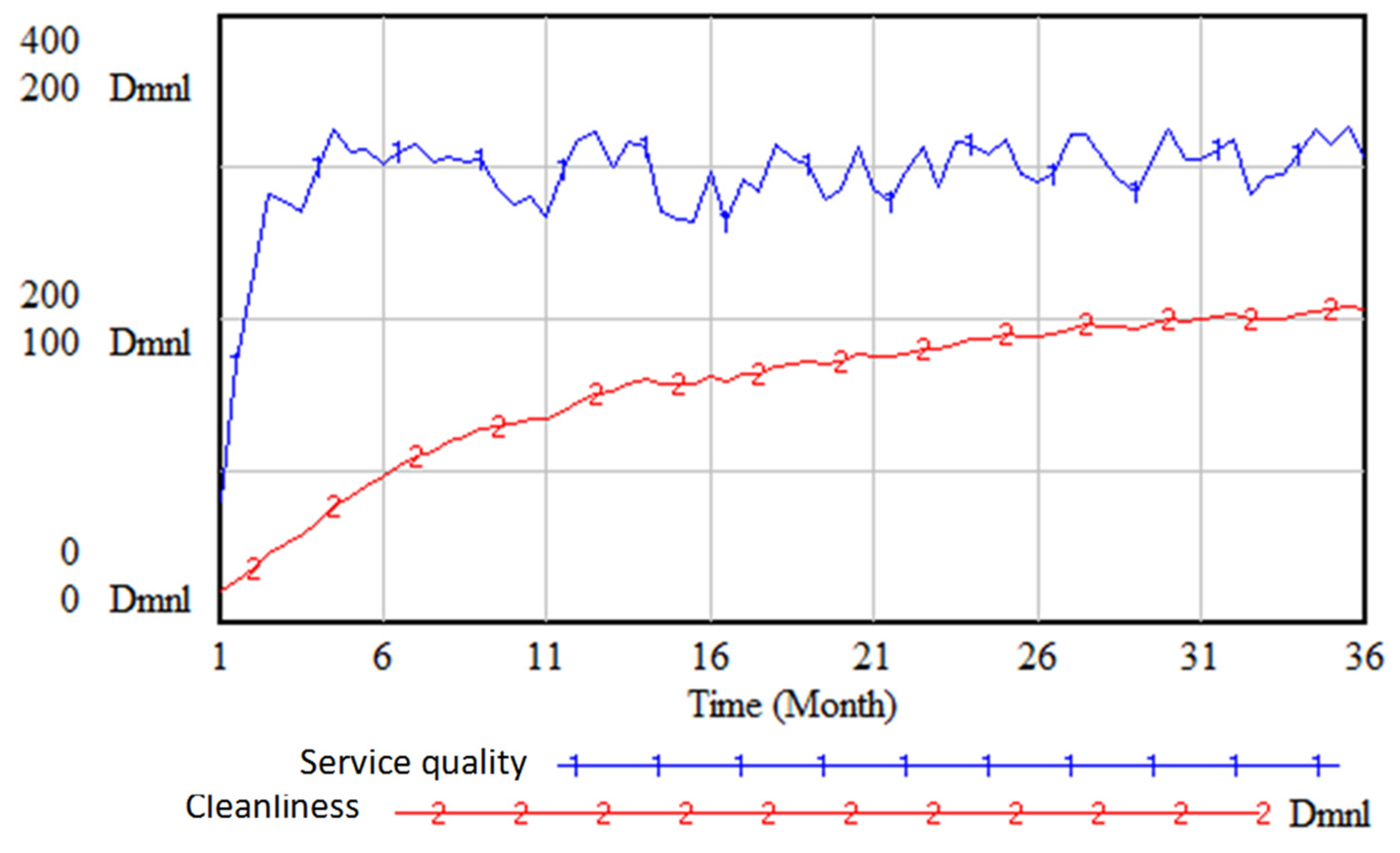

3.2. Development of the Dynamic Evaluation Model

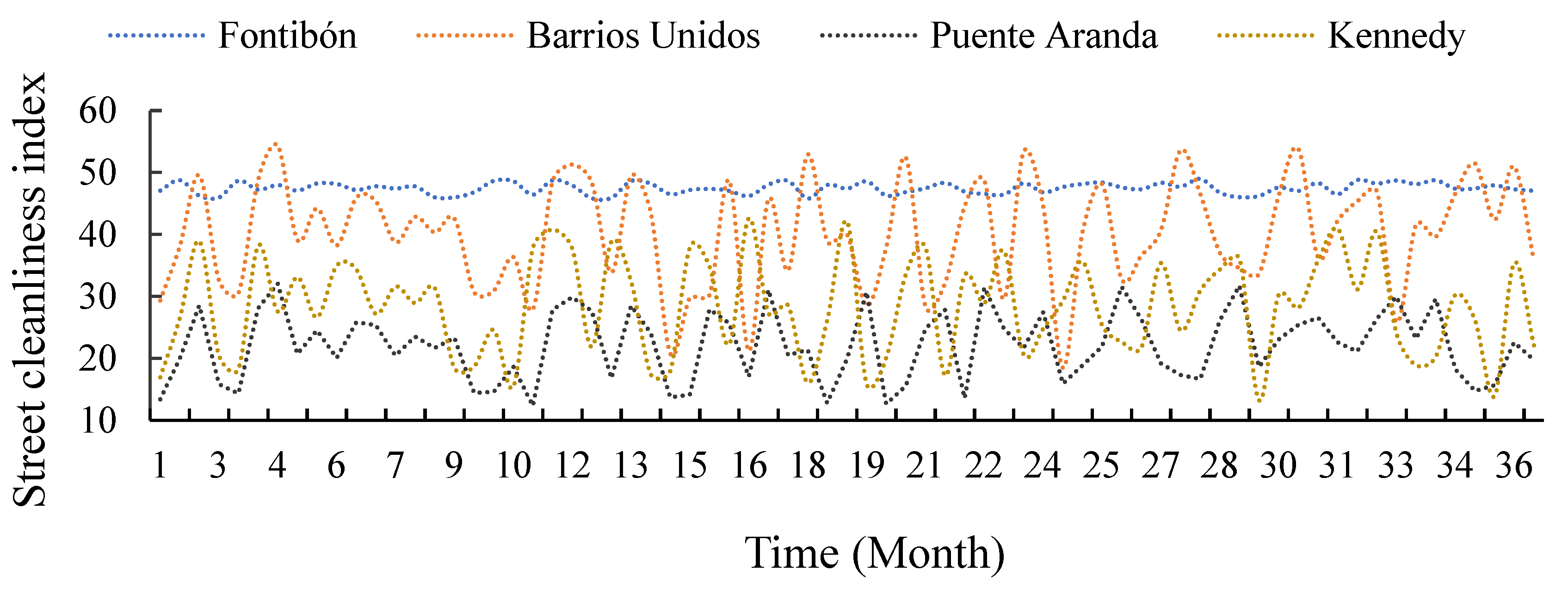

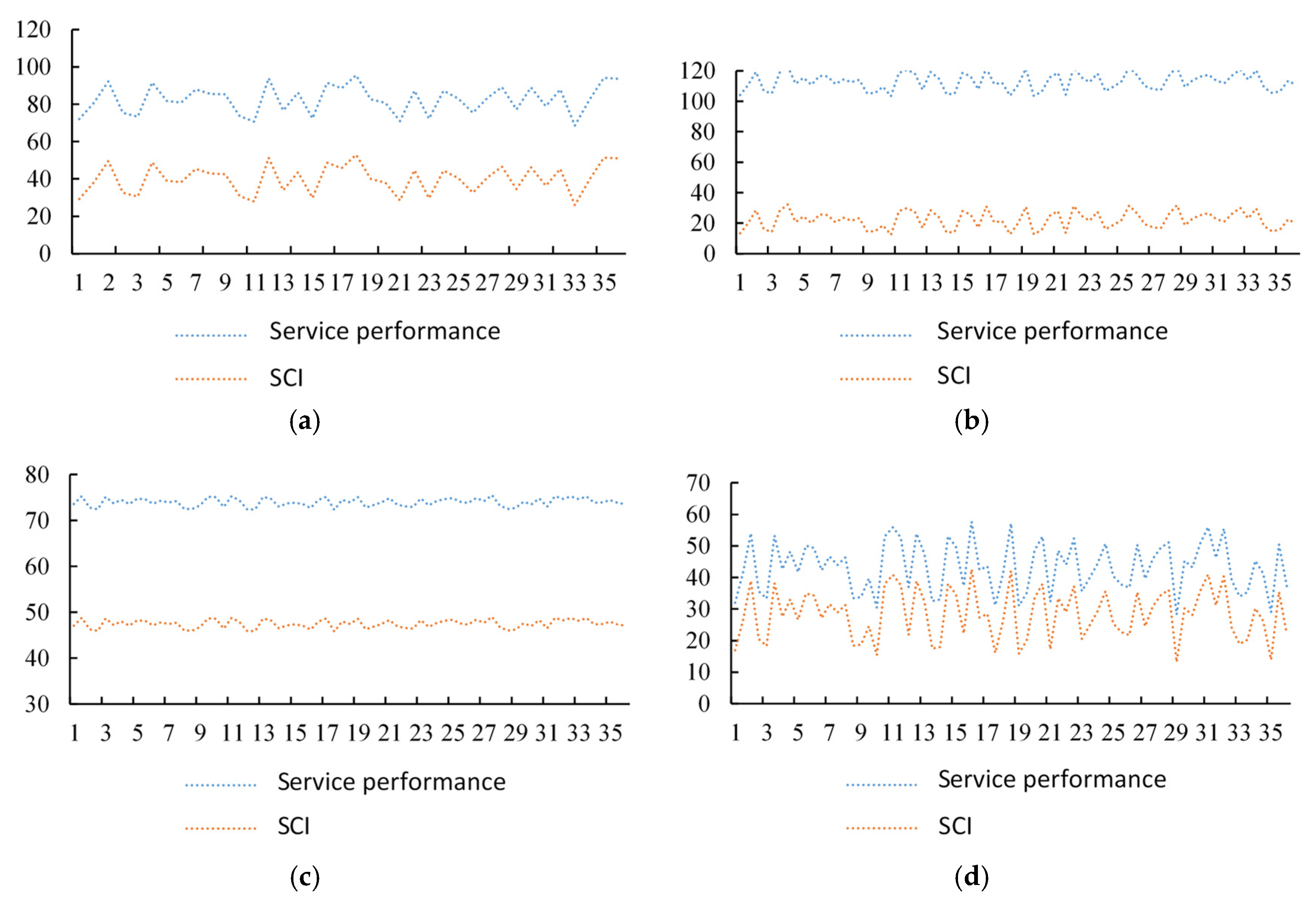

3.3. Dynamic Model Validation

3.4. Citizen Perception

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The evaluation of street sweeping services through the developed model suggests that technical/operational efficiency, although essential, proves insufficient to ensure system sustainability if not articulated with citizen perception.

- (2)

- The results indicate that geometric and spatial variables, along with climatic factors, significantly condition the cleanliness level, generating efficiency reductions of up to 100%. However, model validation reveals a critical gap between operational cleanliness and citizen perception, with reductions of up to 64.2% in the comprehensive service assessment.

- (3)

- The inclusion of perception indicators with acceptable validity (Cronbach’ α = 0.770) highlights the need to consider perceptual variables, such as collection timeliness and personnel attitude, which explain a relevant proportion of citizen satisfaction. In this way, the proposed dynamic model is a solid tool for supporting public management, as it integrates operational and perceptual variables to potentially optimize resources, reduce socio-environmental impacts, and reinforce institutional legitimacy in the provision of urban street cleaning services.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, G.; Vyas, S.; Sharma, S.N.; Dehalwar, K. Challenges of Environmental Health in Waste Management for Peri-Urban Areas. In Solid Waste Management: Advances and Trends to Tackle the SDGs; Nasr, M., Negm, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 149–168. ISBN 978-3-031-60684-7. [Google Scholar]

- Baud, I.; Grafakos, S.; Hordijk, M.; Post, J. Quality of Life and Alliances in Solid Waste Management: Contributions to Urban Sustainable Development. Cities 2001, 18, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo, S.J.; Williams, E.S.; Brooks, B.W. Street Dust: Implications for Stormwater and Air Quality, and Environmental Management Through Street Sweeping. In Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology Volume 233; Whitacre, D.M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 71–128. ISBN 978-3-319-10479-9. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, F.; Querol, X.; Johansson, C.; Nagl, C.; Alastuey, A. A Review on the Effectiveness of Street Sweeping, Washing and Dust Suppressants as Urban PM Control Methods. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 3070–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejía, C.A.Z.; Pinzón, E.C.L.; González, J.T. Influence of traffic in the heavy metals accumulation on urban roads: Torrelavega (spain)-soacha (colombia). Rev. Fac. Ing. 2013, 67, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Wiseman, C.L.S. Examining the Effectiveness of Municipal Street Sweeping in Removing Road-Deposited Particles and Metal(Loid)s of Respiratory Health Concern. Environ. Int. 2024, 187, 108697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-L.; Deng, Y.; Lin, M.-Y.; Huang, S.-W. Do the Street Sweeping and Washing Work for Reducing the Near-Ground Levels of Fine Particulate Matter and Related Pollutants? Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2022, 23, 220338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, A.; Datta, D.K.; Bonyadinejad, G.; Salehi, M. Partitioning of Heavy Metals in Sediments and Microplastics from Stormwater Runoff. Chemosphere 2023, 332, 138844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Barreiro, M.d.P.; Pinilla-Castañeda, R.D.; Zafra-Mejía, C.A. Temporal assessment of the heavy metals (Pb and Cu) concentration associated with the road sediment: Fontibón- barrios unidos (Bogotá D.C., Colombia). Ing. Univers. 2015, 19, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryzin, G.G.; Immerwahr, S.; Altman, S. Measuring Street Cleanliness: A Comparison of New York City’s Scorecard and Results from a Citizen Survey. Public Adm. Rev. 2008, 68, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, A.; Rodríguez, M.L.; García-Maraver, Á.; Zamorano, M. An Index to Quantify Street Cleanliness: The Case of Granada (Spain). Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, B.; Guillamón, M.-D.; Martínez-Córdoba, P.-J.; Ríos, A.-M. Influence of Selected Aspects of Local Governance on the Efficiency of Waste Collection and Street Cleaning Services. Waste Manag. 2021, 126, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghinolfi, D.; Paolucci, M.; Robba, M.; Taramasso, A.C. A Dynamic Optimization Model for Solid Waste Recycling. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henao-Rodríguez, C.; Lis-Gutiérrez, J.P.; Sierra, A.S.G. Factors Influencing Environmental Awareness and Solid Waste Management Practices in Bogotá: An Analysis Using Machine Learning. Air Soil Water Res. 2024, 17, 11786221241261188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.S. The Urban, Social, and Environmental Impact of Centralized Waste Systems: A Study on Segregation and Local Alternatives for the Doña Juana Landfill in Bogotá, Colombia. Master’s Thesis, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá. Informe Anual de Calidad de Aire de Bogotá. 2022. Available online: http://rmcab.ambientebogota.gov.co/home/text/1512 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Enciso-Díaz, W.C.; Zafra-Mejía, C.A.; Hernández-Peña, Y.T. Global Trends in Air Pollution Modeling over Cities Under the Influence of Climate Variability: A Review. Environments 2025, 12, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, C.R.; Su, W.; Nassel, A.F.; Agne, A.A.; Cherrington, A.L. Area Based Stratified Random Sampling Using Geospatial Technology in a Community-Based Survey. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkoski, H.; Fowler, B.; Mooney, R.; Pappas, L.; Dixon, B.L.; Pinzon, L.M.; Winkler, J.; Kepka, D. Pilot Test of Survey to Assess Dental and Dental Hygiene Student Human Papillomavirus-Related Oropharyngeal Cancer Knowledge, Perceptions, and Clinical Practices. J. Cancer Educ. 2018, 33, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, A.T.; Jelili, M.O. Clarifying Likert Scale Misconceptions for Improved Application in Urban Studies. Qual. Quant. 2023, 57, 1337–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Dong, H.; Geng, Y.; Tian, X.; Liu, C.; Li, H. Policy Impacts on Municipal Solid Waste Management in Shanghai: A System Dynamics Model Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinha, A.C.H.; Sagawa, J.K. A System Dynamics Modelling Approach for Municipal Solid Waste Management and Financial Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, I.; Gutiérrez, V.; Collantes, F.; Gil, D.; Revilla, R.; Luis Gil, J. Developing an Indicators Plan and Software for Evaluating Street Cleanliness and Waste Collection Services. J. Urban Manag. 2017, 6, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-T.; Chao, H.-R.; Cheng, Y.-F. Forecasting and Controlling of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) in the Kaohsiung City, Taiwan, by Using System Dynamics Modeling. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 9571–9579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhan, W.; Wang, S. Uncertain Water Environment Carrying Capacity Simulation Based on the Monte Carlo Method–System Dynamics Model: A Case Study of Fushun City. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, B.W.; Sim, C.H. Comparisons of Various Types of Normality Tests. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2011, 81, 2141–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-Y.; Wei, Z.-W.; Wang, B.-H.; Han, X.-P. Measuring Mixing Patterns in Complex Networks by Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2016, 451, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, A.; Christodoulou, P.; Zinonos, Z. Citizens’ Perception of Smart Cities: A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhns, H.; Etyemezian, V.; Green, M.; Hendrickson, K.; McGown, M.; Barton, K.; Pitchford, M. Vehicle-Based Road Dust Emission Measurement—Part II: Effect of Precipitation, Wintertime Road Sanding, and Street Sweepers on Inferred PM10 Emission Potentials from Paved and Unpaved Roads. Atmos. Environ. 2003, 37, 4573–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fussell, J.C.; Franklin, M.; Green, D.C.; Gustafsson, M.; Harrison, R.M.; Hicks, W.; Kelly, F.J.; Kishta, F.; Miller, M.R.; Mudway, I.S.; et al. A Review of Road Traffic-Derived Non-Exhaust Particles: Emissions, Physicochemical Characteristics, Health Risks, and Mitigation Measures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6813–6835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas, S.; Trejos, E.M.; Aristizábal, B.H.; Pereira, G.M.; Hernández, J.M.; Herrera Murillo, J.; Ramírez, O.; Silva, L.F.O.; Amato, F.; Rojas, N.Y.; et al. Spatial Distribution and Chemical Composition of Road Dust in Two High-Altitude Latin American Cities. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasov, D.; Ramírez, O.; Luhar, A. Road Dust in Urban and Industrial Environments: Sources, Pollutants, Impacts, and Management. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, P.S.; Komilis, D. A Standardized Inspection Methodology to Evaluate Municipal Solid Waste Collection Performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 246, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, E.; Samir, E. Assessing Citizen Satisfaction Indicators for Urban Public Services to Enhance Quality of Life in Sharm El-Sheikh. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazzi, M.; Zuccato, C.; Schiavon, M.; Rada, E.C. Overview and Possible Approach to Street Sweeping Criticalities. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.-H.; Fang, C.; Evans, G. Spatial Variation of Resuspended Particulate Matter in Urban Environments and Real-World Assessment of Street Sweeping. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 373, 126165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Han, X.; He, J.; Jung, T. Measuring Residents’ Perceptions of City Streets to Inform Better Street Planning through Deep Learning and Space Syntax. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, A.A.; Alavi, N.; Goudarzi, G.; Teymouri, P.; Ahmadi, K.; Rafiee, M. Household Recycling Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices towards Solid Waste Management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 102, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, T. Promoting Public Participation in Household Waste Management: A Survey Based Method and Case Study in Xiamen City, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 144, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Site | Knowledge (%) | Behavior (%) | Positive Perception (%) | SCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kennedy | 44.4 | 60.3 | 30.9 | 27.5 | VH |

| Fontibón | 41.7 | 59.4 | 44.2 | 40.1 | VH |

| Puente Aranda | 44.2 | 23.3 | 70.0 | 29.3 | VH |

| Barrios Unidos | 27.9 | 33.3 | 48.1 | 57.3 | VH |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rubio-Calderón, L.C.; Zafra-Mejía, C.A.; Rondón-Quintana, H.A. Dynamic Simulation Model for Urban Street Sweeping: Integrating Performance and Citizen Perception. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120518

Rubio-Calderón LC, Zafra-Mejía CA, Rondón-Quintana HA. Dynamic Simulation Model for Urban Street Sweeping: Integrating Performance and Citizen Perception. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):518. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120518

Chicago/Turabian StyleRubio-Calderón, Laura Catalina, Carlos Alfonso Zafra-Mejía, and Hugo Alexander Rondón-Quintana. 2025. "Dynamic Simulation Model for Urban Street Sweeping: Integrating Performance and Citizen Perception" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120518

APA StyleRubio-Calderón, L. C., Zafra-Mejía, C. A., & Rondón-Quintana, H. A. (2025). Dynamic Simulation Model for Urban Street Sweeping: Integrating Performance and Citizen Perception. Urban Science, 9(12), 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120518