Urban Sound Classification for IoT Devices in Smart City Infrastructures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

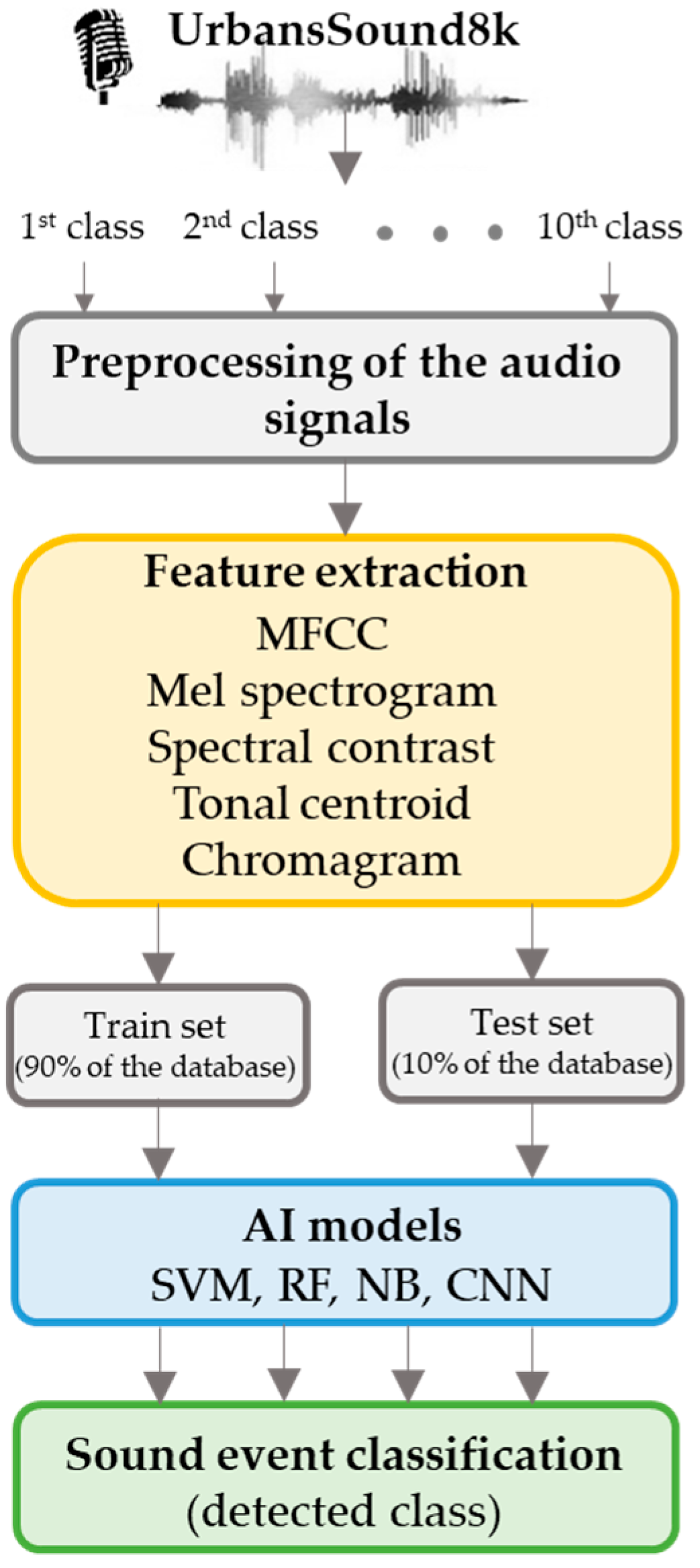

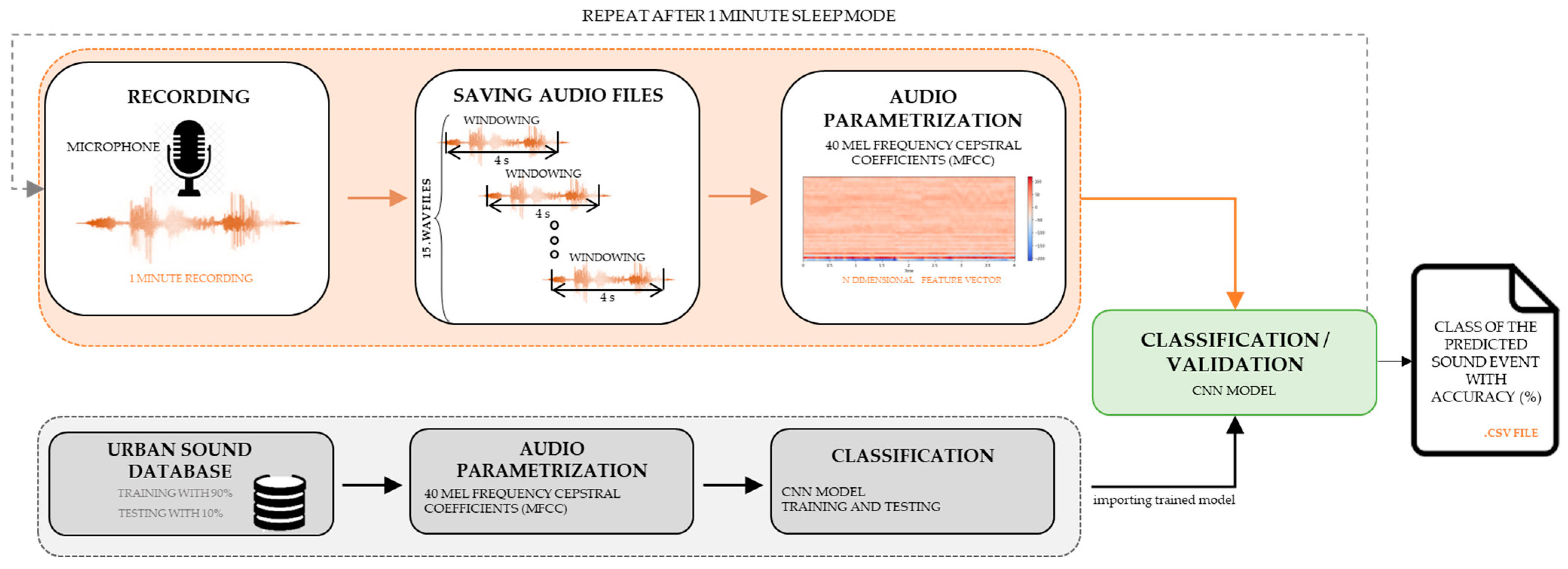

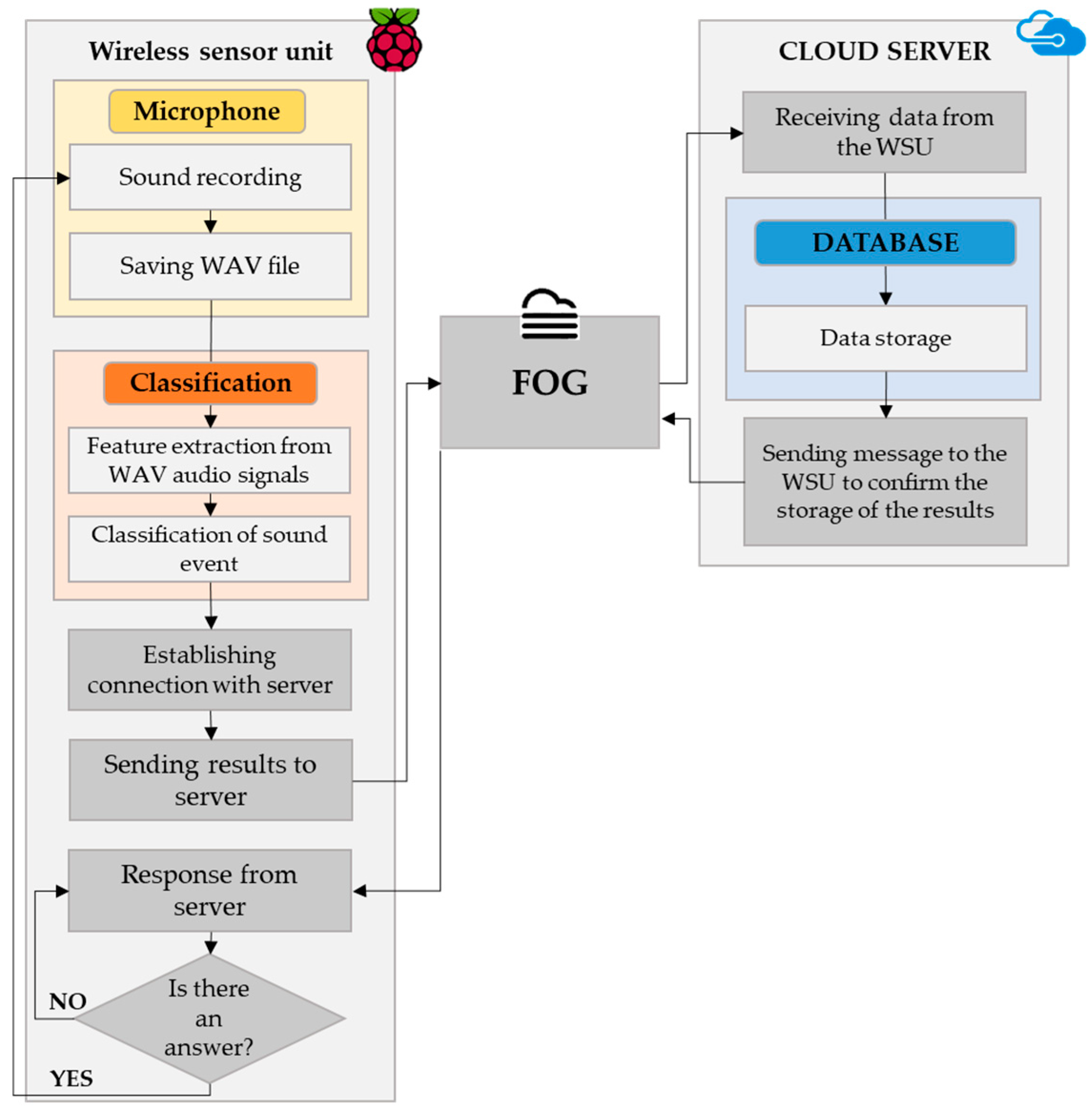

2.1. System Architecture

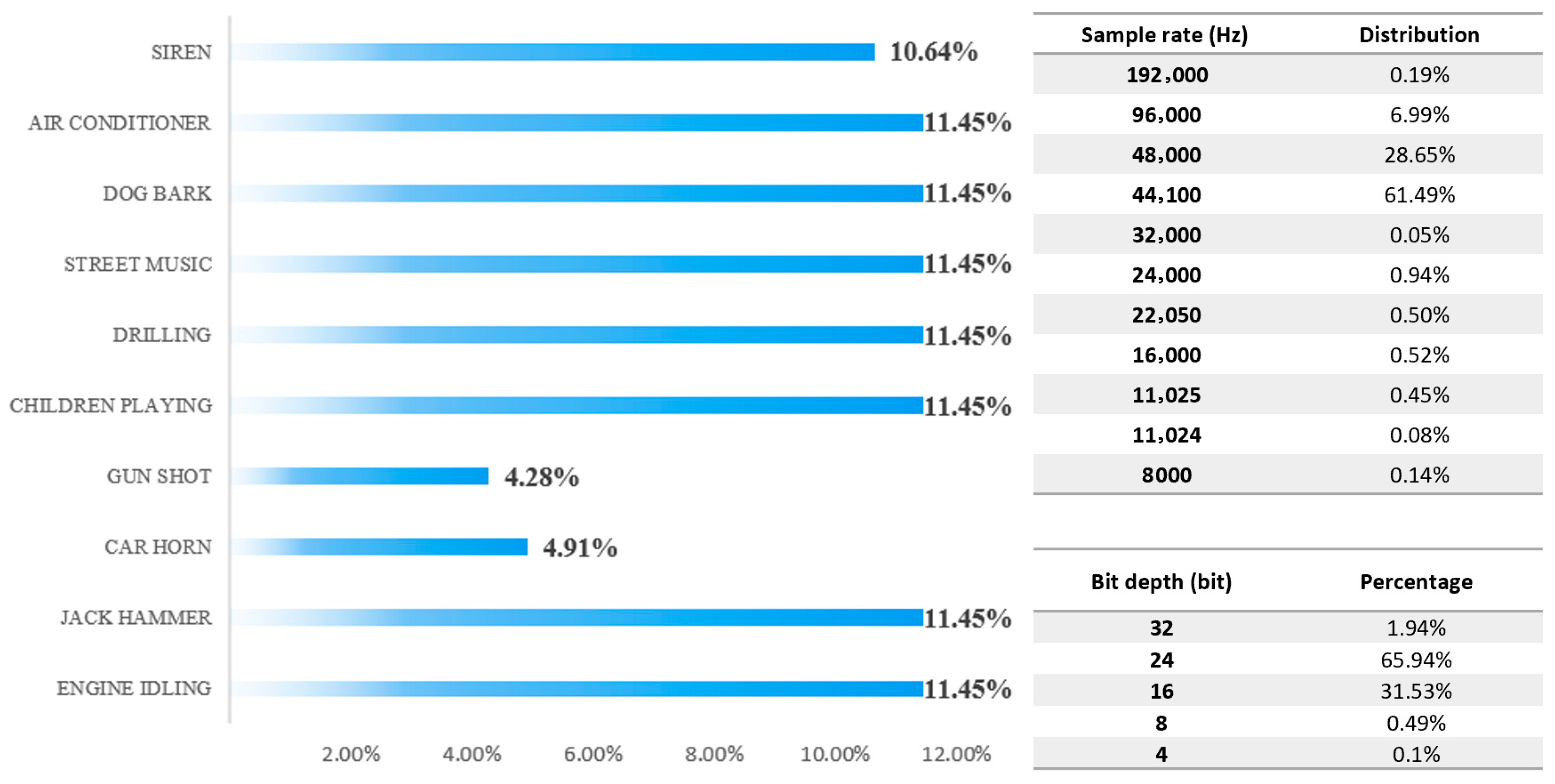

2.2. Analysis and Preprocessing of the Dataset of Acoustic Urban Sound Events

2.3. Feature Extraction

2.4. Machine Learning Algorithms

2.4.1. Random Forest

2.4.2. Support Vector Machines

2.4.3. Naive Bayes

2.4.4. Hyperparametrization

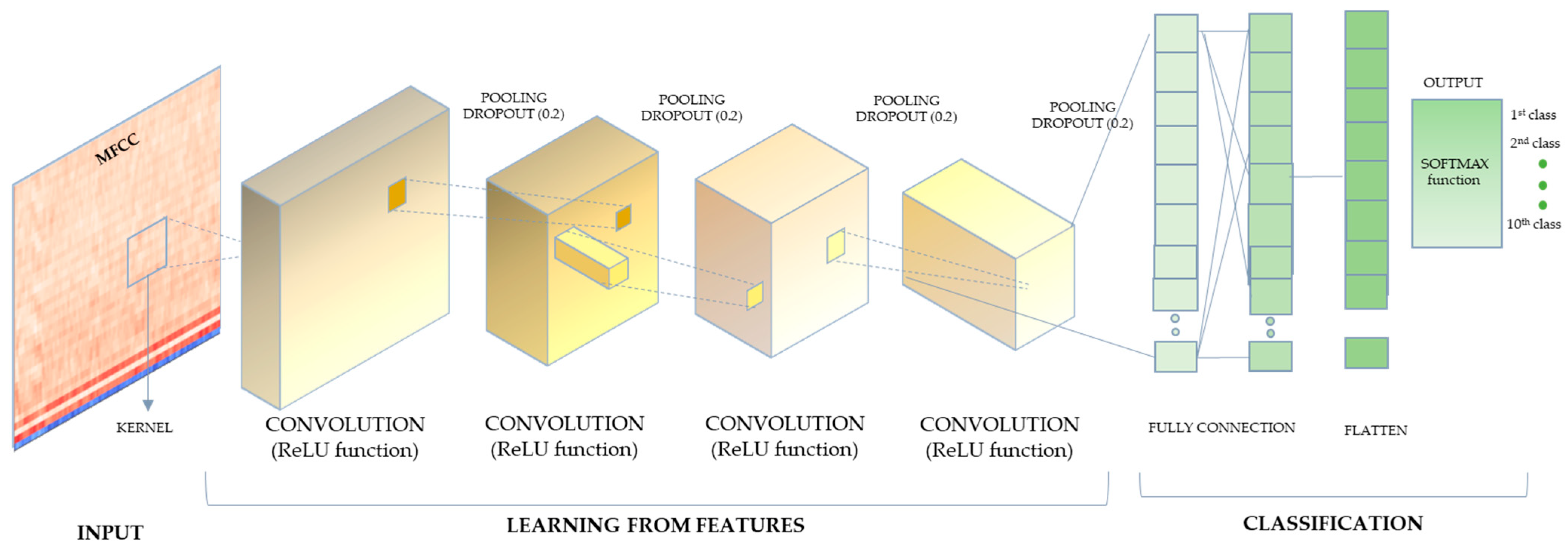

2.5. Convolutional Neural Networks

3. Results

3.1. Classic Machine Learning Algorithms

3.1.1. Results from Testing 48 Different Models for Feature Vectors and ML Algorithms

3.1.2. Applying Hyperparameter Optimization

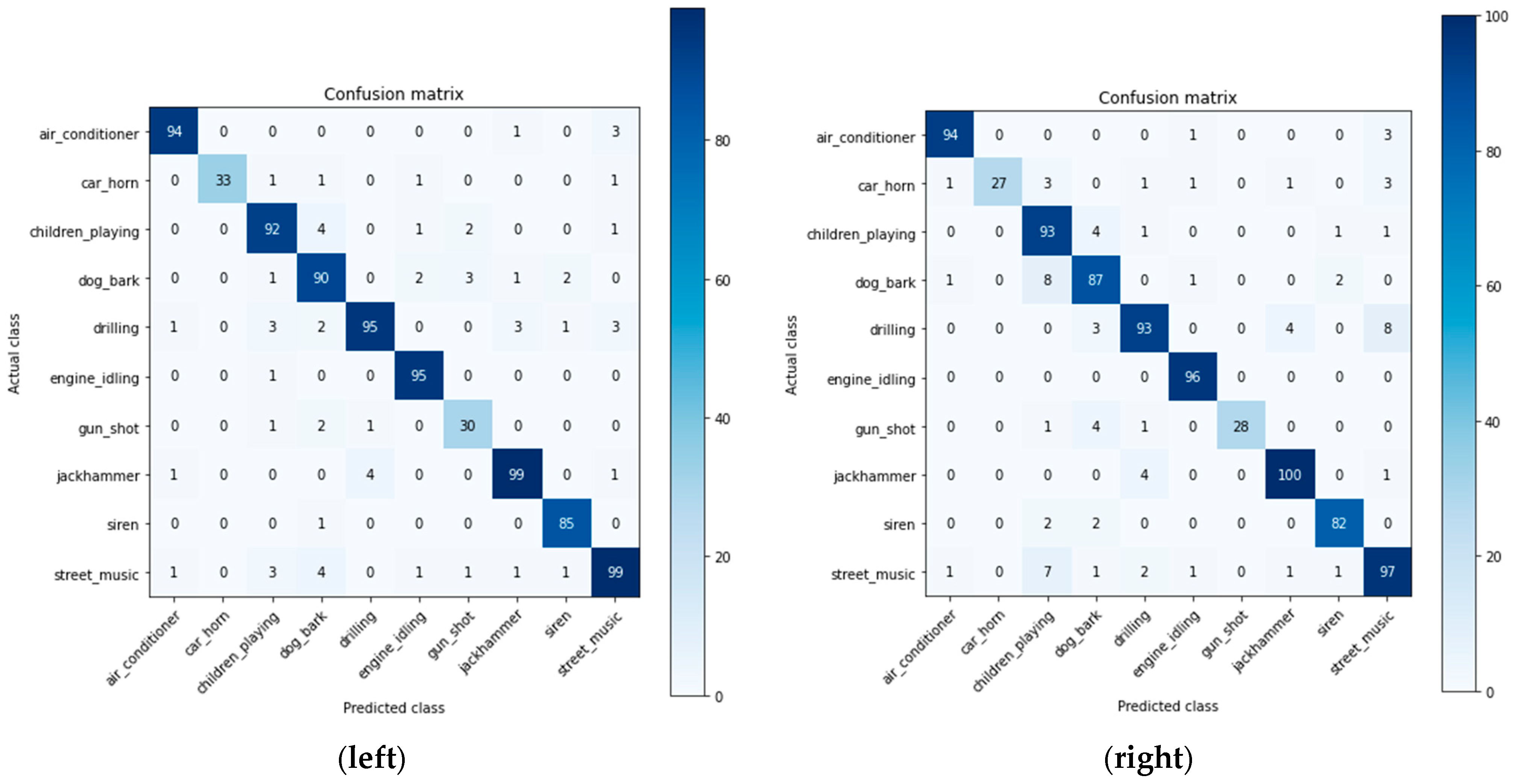

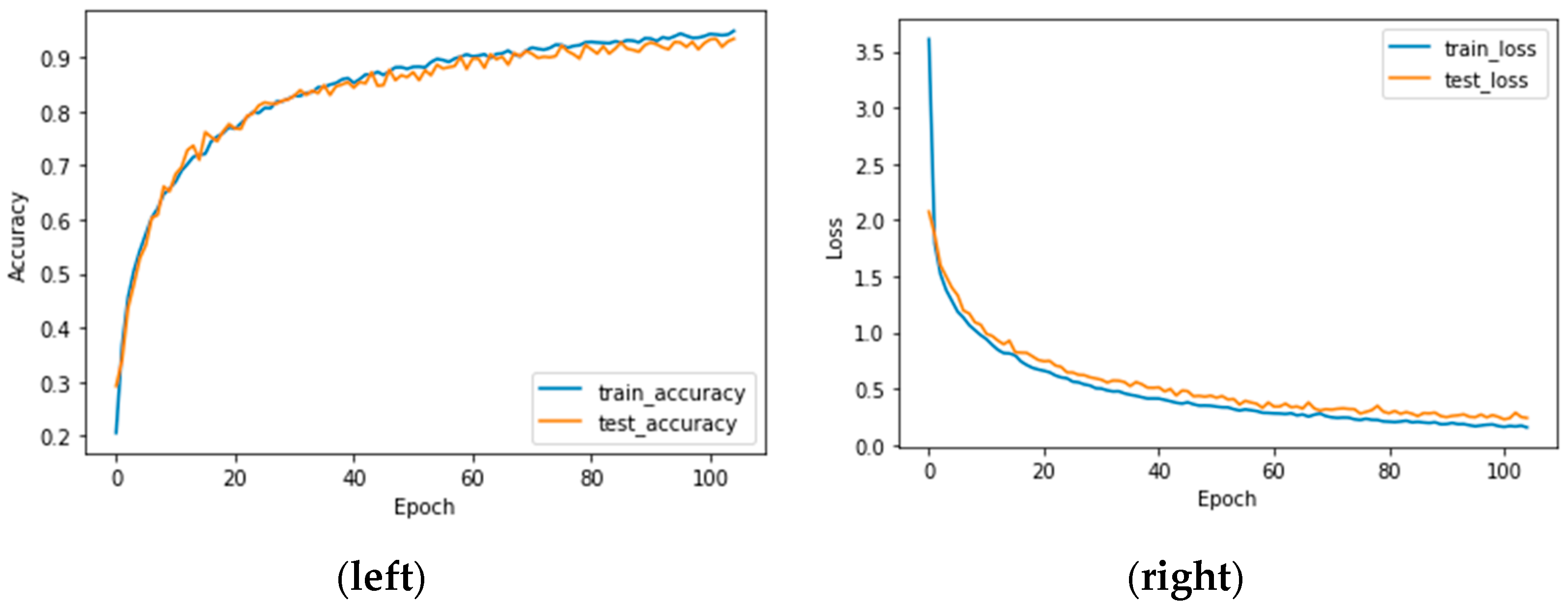

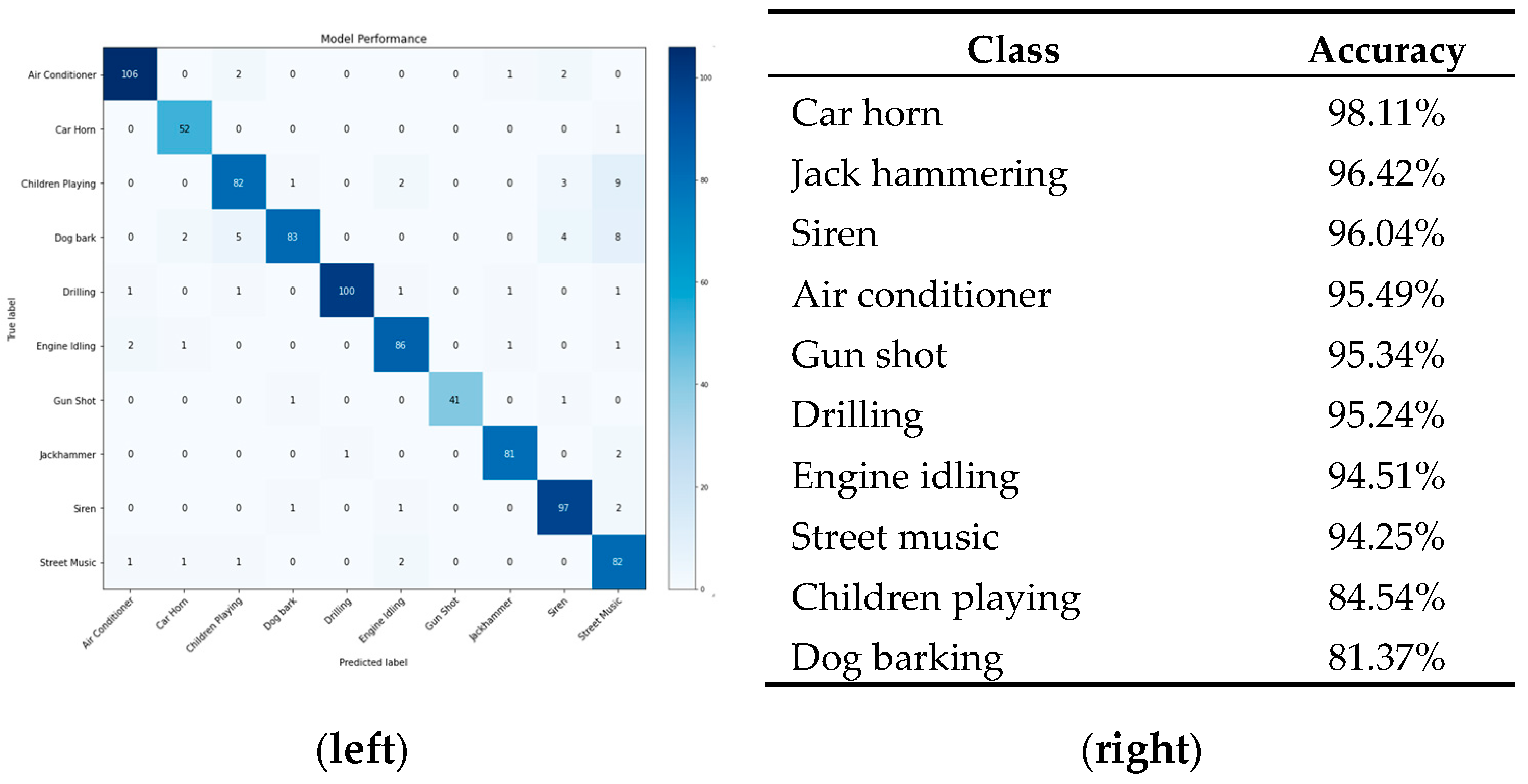

3.2. Results from Testing CNN

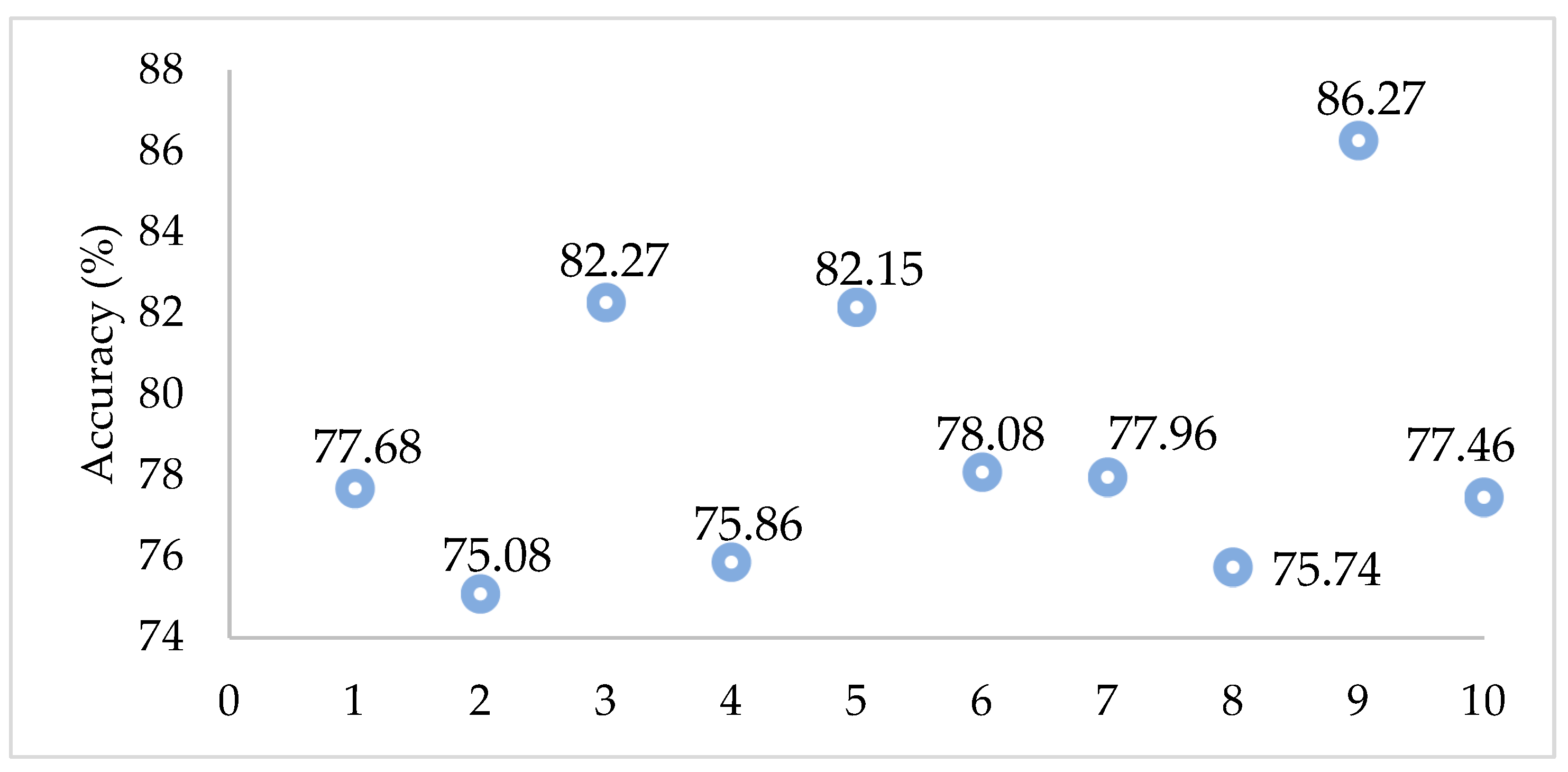

3.3. Real-Time Validation and Application on Real System

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Green Paper on Future Noise Policy. 1996. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/8d243fb5-ec92-4eee-aac0-0ab194b9d4f3/language-en (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report: 2003: Shaping the Future. 2003. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC313882/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Blanes, N.; Fons, J.; Houthuijs, D.; Swart, W.; de la Maza, M.S.; Ramos, M.J.; Castell, N.; van Kempen, E. Noise in Europe 2017: Updated Assessment; European Topic Centre on Air Pollution and Climate Change Mitigation (ETC/ACM): Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Handbook on the Implementation of EC Environmental Legislation, Section 9—Noise Legislation. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/2b832b9d-9aea-11e6-868c-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- World Health Organization. Guidance on Environmental Noise, Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/compendium-on-health-and-environment/environmental-noise (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Zannin, P.H.T.; Engel, M.S.; Fiedler, P.E.K.; Bunn, F. Characterization of environmental noise based on noise measurements, noise mapping and interviews: A case study at a university campus in Brazil. Cities 2013, 31, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąkowski, A.; Radziszewski, L.; Dekýš, V.; Šwietlik, P. Frequency analysis of urban traffic noise. In Proceedings of the 2019 20th International Carpathian Control Conference (ICCC), Wieliczka, Poland, 26–29 May 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld, S.A.; Matheson, M.P. Noise pollution: Non-auditory effects on health. Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 68, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive END 2002/49/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 June 2002 Relating to the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 1996-1; Acoustics—Description, Measurement and Assessment of Environmental Noise—Part 1: Basic Quantities and Assessment Procedures. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 1996-2; Acoustics—Description, Measurement and Assessment of Environmental Noise—Part 2: Determination of Environmental Noise Levels. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Socoró, J.C.; Sevillano, X.; Alías, F. Analysis and automatic detection of anomalous noise events in real recordings of road traffic noise for the LIFE DYNAMAP project. In Proceedings of the INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference Proceedings, Hamburg, Germany, 21–24 August 2016; Institute of Noise Control Engineering: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2016; Volume 253, pp. 1943–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Socoró, J.C.; Alías, F.; Alsina, R.M.; Sevillano, X.; Camins, Q. B3-Report Describing the ANED Algorithms for Low and High Computation Capacity Sensors; Report B3; Funitec La Salle: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sevillano, X.; Socoró, J.C.; Alías, F.; Bellucci, P.; Peruzzi, L.; Radaelli, S.; Coppi, P.; Nencini, L.; Cerniglia, A.; Bisceglie, A.; et al. DYNAMAP—Development of low cost sensors networks for real time noise mapping. Noise Mapp. 2016, 3, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillas, J.M.B.; Gozalo, G.R.; González, D.M.; Moraga, P.A.; Vílchez-Gómez, R. Noise pollution and urban planning. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2018, 4, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DYNAMAP Report: State of the Art on Sound Source Recognition and Anomalous Event Elimination. Project: Dynamic Acoustic Mapping—Development of Low-Cost Sensors Networks for Real Time Noise Mapping LIFE Dynamap Report A1; LIFE13 ENV/IT/001254; Funitec La Salle: Barcelona, Spain, 2015.

- Gygi, B. Factors in the Identification of Environmental Sounds. Ph.D. Thesis, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bountourakis, V.; Vrysis, L.; Papanikolaou, G. Machine learning algorithms for environmental sound recognition: Towards soundscape semantics. In Proceedings of the Audio Mostly 2015 on Interaction with Sound; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, J.P.; Silva, C.; Nov, O.; Dubois, R.L.; Arora, A.; Salamon, J.; Doraiswamy, H. Sonyc: A System for Monitoring, Analyzing, and Mitigating Urban Noise Pollution. Commun. ACM 2019, 62, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaña-Vila, E.; Navarro, J.; Borda-Fortuny, C.; Stowell, D.; Alsina-Pagès, R.M. Low cost distributed acoustic sensor network for real-time urban sound monitoring. Electronics 2020, 9, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvo, D.; Piñero, G.; Arce, P.; Gonzalez, A. A Low-cost Wireless Acoustic Sensor Network for the Classification of Urban Sounds. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Symposium on Performance Evaluation of Wireless Ad Hoc, Sensor, & Ubiquitous Networks, Alicante, Spain, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Qin, H.; Song, X.; Wang, M.; Qiu, H.; Zhou, Z. Wireless Sensor Networks for Noise Measurement and Acoustic Event Recognitions in Urban Environments. Sensors 2020, 20, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abayomi-Alli, O.O.; Damaševičius, R.; Qazi, A.; Adedoyin-Olowe, M.; Misra, S. Data augmentation and deep learning methods in sound classification: A systematic review. Electronics 2022, 11, 3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Yin, B.; Huang, X.; Xu, J.; Du, Z. Environmental sound classification using temporal-frequency attention based convolutional neural network. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artuso, F.; Fidecaro, F.; D’Alessandro, F.; Iannace, G.; Licitra, G.; Pompei, G.; Fredianelli, L. Identifying optimal feature sets for acoustic signal classification in environmental noise measurements. In INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference Proceedings; Institute of Noise Control Engineering: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2024; Volume 270, pp. 7540–7549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Garg, N.K. Environmental Sound Classification: A descriptive review of the literature. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2022, 16, 200115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoudi, M.; Verma, S.; Jain, R. Urban sound classification using CNN. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Coimbatore, India, 20–22 January 2021; pp. 583–589. [Google Scholar]

- Baucas, M.J.; Spachos, P. Edge-based data sensing and processing platform for urban noise classification. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2024, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranmal, D.; Ranasinghe, P.; Paranayapa, T.; Meedeniya, D.; Perera, C. Esc-nas: Environment sound classification using hardware-aware neural architecture search for the edge. Sensors 2024, 24, 3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.F.R.; Oliveira, H.S.; Machado, J.J.; Tavares, J.M.R. Transformers for urban sound classification—A comprehensive performance evaluation. Sensors 2022, 22, 8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, R.; Chaitra, N.C.; Thejaswini, R.; Swapna, H.; Parameshachari, B.D.; Sunil Kumar, D.S. Urban Sound Classification with Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Integrated Intelligence and Communication Systems (ICIICS), Kalaburagi, India, 22–23 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, J.W. Sound Event Recognition in Unstructured Environments Using Spectrogram Image Processing. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Temko, A. Acoustic Event Detection and Classification [Report]. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, X.; Zhou, X.; Hasegawa-Johnson, M.A.; Huang, T.S. Real-world acoustic event detection. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2010, 31, 1543–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Zhou, D.; Madani, K. Performance analysis of multiple aggregated acoustic features for environment sound classification. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 158, 107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, X.; Alías, F. Hierarchical classification of environmental noise sources considering the acoustic signature of vehicle pass-bys. Arch. Acoust. 2012, 37, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, B.; W Happi, A.; Braeken, A.; Touhafi, A. Evaluation of classical machine learning techniques towards urban sound recognition on embedded systems. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezhenin, I.; Bogach, N.; Pyshkin, E. Urban sound classification using long short-term memory neural network. In Proceedings of the 2019 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems (FedCSIS), Leipzig, Germany, 1–4 September 2019; IEEE: Leipzig, Germany, 2019; pp. 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Alsouda, Y.; Pllana, S.; Kurti, A. Iot-based urban noise identification using machine learning: Performance of SVM, KNN, bagging, and random forest. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Omni-Layer Intelligent Systems, Crete, Greece, 5–7 May 2019; pp. 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, I.; Yadav, P.; Gupta, N.; Yadav, S. Urban Sound Classification Using Machine Learning and Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Recent Trends in Computing, Ghaziabad, India, 17–18 April 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Fusaro, G.; Garai, M. Acoustic requalification of an urban evolving site and design of a noise barrier: A case study at the Bologna engineering school. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, S.; Zhang, S.; Qiao, T.; Cao, S. Learning attentive representations for environmental sound classification. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 130327–130339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, Z.; Su, S.F.; Tran, Q.V. Spectral images based environmental sound classification using CNN with meaningful data augmentation. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 172, 107581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulimani, M.; Koolagudi, S.G. Segmentation and characterization of acoustic event spectrograms using singular value decomposition. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 120, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, C.V.; Ellis, D.P. Spectral vs. spectro-temporal features for acoustic event detection. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Workshop on Applications of Signal Processing to Audio and Acoustics (WASPAA), New Paltz, NY, USA, 16–19 October 2011; pp. 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Hong, F.; Feng, H.; Zhai, Y.; Chen, Y. Environmental Sound Classification Based on Stacked Concatenated DNN using Aggregated Features. J. Signal Process. Syst. 2021, 93, 1287–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C.; Liu, H.; Li, X. Multitask learning of time-frequency CNN for sound source localization. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 40725–40737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorla, S.; Comai, S.; Masciadri, A.; Salice, F. BigEar: Ubiquitous Wireless Low-Budget Speech Capturing Interface. J. Comput. Commun. 2017, 5, 60–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baucas, M.J.; Spachos, P. A scalable IoT-fog framework for urban sound sensing. Comput. Commun. 2020, 153, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manvell, D. Utilising the strengths of different sound sensor networks in smart city noise management. In Proceedings of the EuroNoise 2015, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 31 May–3 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alías, F.; Alsina-Pagès, R.M. Review of wireless acoustic sensor networks for environmental noise monitoring in smart cities. J. Sens. 2019, 2019, 7634860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mydlarz, C.; Salamon, J.; Bello, J.P. The implementation of low-cost urban acoustic monitoring devices. Appl. Acoust. 2017, 117, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, M.; Karimi, E.; Nassiri, P.; Monazzam, M.R.; Taghavi, L. Hierarchal assessment of noise pollution in urban areas–A case study. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 34, pp.95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollosi, D.; Nagy, G.; Rodigast, R.; Goetze, S.; Cousin, P. Enhancing wireless sensor networks with acoustic sensing technology: Use cases, applications & experiments. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Green Computing and Communications and IEEE Internet of Things and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing, Beijing, China, 20–23 August 2013; pp. 335–342. [Google Scholar]

- Baucas, M.J.; Spachos, P. Using cloud and fog computing for large scale IoT-based urban sound classification. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2020, 101, 102013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benocci, R.; Molteni, A.; Cambiaghi, M.; Angelini, F.; Roman, H.E.; Zambon, G. Reliability of Dynamap traffic noise prediction. Appl. Acoust. 2019, 156, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, P.; Peruzzi, L.; Zambon, G. LIFE DYNAMAP project: The case study of Rome. Appl. Acoust. 2017, 117, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domazetovska, S.; Gavriloski, V.; Anachkova, M. Influence of several audio parameters in urban sound event classification. In INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference Proceedings; Institute of Noise Control Engineering: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2023; Volume 265, pp. 2777–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domazetovska, S.; Pecioski, D.; Gavriloski, V.; Mickoski, H. IoT smart city framework using AI for urban sound classification. In INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference Proceedings; Institute of Noise Control Engineering: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2023; Volume 265, pp. 2767–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domazetovska Markovska, S.; Anachkova, M.; Pecioski, D.; Gavriloski, V. Advanced concept for noise monitoring in smart cities through wireless sensor units with AI classification technologies. In INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference Proceedings; Institute of Noise Control Engineering: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2024; Volume 270, pp. 2779–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temko, A.; Nadeu, C.; Macho, D.; Malkin, R.; Zieger, C.; Omologo, M. Acoustic event detection and classification. In Computers in the Human Interaction Loop; Springer: London, UK, 2009; pp. 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon, J.; Jacoby, C.; Bello, J.P. A dataset and taxonomy for urban sound research. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Orlando, FL, USA, 3–7 November 2014; pp. 1041–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, I.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Z.; Song, Y.; Xiao, W.; Phan, H. Continuous robust sound event classification using time-frequency features and deep learning. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitrović, D.; Zeppelzauer, M.; Breiteneder, C. Features for content-based audio retrieval. In Advances in Computers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 78, pp. 71–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Umapathy, K.; Krishnan, S. Trends in audio signal feature extraction methods. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 158, 107020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Narayanan, S.; Kuo, C.C.J. Environmental sound recognition with time–frequency audio features. IEEE Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2009, 17, 1142–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFee, B.; Raffel, C.; Liang, D.; Ellis, D.P.W.; McVicar, M.; Battenberg, E.; Nieto, O. librosa: Audio and music signal analysis in Python. In Proceedings of the 14th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 6–12 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tosi, S. Matplotlib for Python Developers; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2009; Volume 307. [Google Scholar]

- Rossant, C. Learning IPython for Interactive Computing and Data Visualization; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Mach. Learn. 1996, 24, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.P. Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih-Wei, H.; Chih-Chung, C.; Chih-Jen, L. A Practical Guide to Support Vector Classification. Technical Report. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, National Taiwan University, Taiwan, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, W.S. What is a support vector machine? Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1565–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. The optimality of naive Bayes. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society Conference, Miami Beach, FL, USA, 12–14 May 2004; Volume 1, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Rish, I. An empirical study of the naive Bayes classifier. In Proceedings of the IJCAI 2001 Workshop on Empirical Methods in Artificial Intelligence, Seattle, WA, USA, 4–10 August 2001; Volume 3, pp. 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rennie, J.D.; Shih, L.; Teevan, J.; Karger, D.R. Tackling the poor assumptions of naive bayes text classifiers. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-03), Washington, DC, USA, 21–24 August 2003; pp. 616–623. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y. Gradient-based optimization of hyperparameters. Neural Comput. 2000, 12, 1889–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luketina, J.; Berglund, M.; Greff, K.; Raiko, T. Scalable gradient-based tuning of continuous regularization hyperparameters. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016; pp. 2952–2960. [Google Scholar]

- DeCastro-García, N.; Muñoz Castañeda, Á.L.; Escudero García, D.; Carriegos, M.V. Effect of the sampling of a dataset in the hyperparameter optimization phase over the efficiency of a machine learning algorithm. Complexity 2019, 6278908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nat. 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezdan, T.; Džakula, N.B. Convolutional Neural Network Layers and Architectures. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference on Information Technology and Data Related Research, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 19–21 July 2019; pp. 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Goodfellow, I.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. Introduction to Convolutional Neural Networks; National Key Lab for Novel Software Technology, Nanjing University: Nanjing, China, 2017; Volume 5, p. 495. Available online: https://project.inria.fr/quidiasante/files/2021/06/CNN.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Duchi, J.; Hazan, E.; Singer, Y. Adaptive subgradient methods for online learning and stochastic optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2121–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.E. A practical guide to training restricted Boltzmann machines. In Neural Networks: Tricks of the Trade; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 599–619. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.; Deng, L.; Yu, D.; Dahl, G.E.; Mohamed, A.R.; Jaitly, N.; Senior, A.; Vanhoucke, V.; Nguyen, P.; Sainath, T.N.; et al. Deep neural networks for acoustic modeling in speech recognition: The shared views of four research groups. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2012, 29, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, M.; Barham, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; Ghemawat, S.; Irving, G.; Isard, M.; et al. TensorFlow: A system for large-scale machine learning. In Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI’16), Savannah, GA, USA, 2–4 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Random Forest | Support Vector Machines | Naive Bayes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MFCC | 55.07% ± 1.36% | 51.05% ± 1.42% | 47.19% ± 1.51% |

| MFCC + SC | 63.56% ± 1.28% | 58.78% ± 1.34% | 50.53% ± 1.47% |

| MFCC + TC | 57.22% ± 1.31% | 50.29% ± 1.39% | 45.04% ± 1.45% |

| MFCC + Ch | 60.08% ± 1.25% | 53.17% ± 1.37% | 47.72% ± 1.49% |

| MFCC + MS | 42.16% ± 1.41% | 49.91% ± 1.38% | 22.33% ± 1.62% |

| MFCC + SC + TC | 65.47% ± 1.22% | 58.66% ± 1.32% | 47.91% ± 1.44% |

| MFCC + SC + Ch | 66.31% ± 1.29% | 59.38% ± 1.33% | 50.78% ± 1.50% |

| MFCC + SC + MS | 58.12% ± 1.42% | 55.45% ± 1.35% | 26.33% ± 1.58% |

| MFCC + TC+ Ch | 61.31% ± 1.26% | 52.78% ± 1.34% | 48.92% ± 1.50% |

| MFCC + TC + MS | 62.22% ± 1.30% | 52.92% ± 1.38% | 48.02% ± 1.48% |

| MFCC + Ch +MS | 57.58% ± 1.33% | 52.21% ± 1.36% | 26.16% ± 1.56% |

| MFCC + SC + TC + Ch | 65.88% ± 1.27% | 58.42% ± 1.35% | 48.98% ± 1.46% |

| MFCC + SC + TC + MS | 60.45% ± 1.31% | 55.13% ± 1.34% | 29.92% ± 1.54% |

| MFCC + SC + Ch + MS | 61.41% ± 1.28% | 57.59% ± 1.33% | 26.28% ± 1.57% |

| MFCC + TC + Ch + MS | 58.13% ± 1.30% | 56.72% ± 1.36% | 26.22% ± 1.55% |

| All 5 parameters | 62.60% ± 1.29% | 55.67% ± 1.36% | 26.40% ± 1.59% |

| Type of Layer | Output Shape | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Convolution2D (16 filters, 2 × 2 kernel size, ReLU activation unit) | (None, 39, 173, 16) | 80 |

| MaxPooling | (None, 19, 86, 16) | 0 |

| Spatial Dropout (0, 2) | (None, 19, 86, 16) | 0 |

| Convolution2D (32 filters, 2 × 2 kernel size, ReLU activation unit) | (None, 18, 85, 32) | 2080 |

| MaxPooling | (None, 9,4 2, 32) | 0 |

| Spatial Dropout (0, 2) | (None, 9, 42, 32) | 0 |

| Convolution2D (64 filters, 2 × 2 kernel size, ReLU activation unit) | (None, 8, 41, 64) | 8256 |

| MaxPooling | (None, 4, 20, 64) | 0 |

| Spatial Dropout (0, 2) | (None, 4, 20, 64) | 0 |

| Convolution2D (128 filters, 2 × 2 kernel size, ReLU activation unit) | (None, 3, 19, 128) | 32896 |

| MaxPooling | (None, 1, 9, 128) | 0 |

| Spatial Dropout (0, 2) | (None, 1, 9, 128) | 0 |

| GlobalAveragePooling2D | (None, 128) | 0 |

| Flatten | (None, 128) | 0 |

| Dense 10 units (SOFTMAX output) | (None, 10) | 1290 |

| TOTAL NUMBER OF TRAINING PARAMETERS 44,602 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Domazetovska Markovska, S.; Gavriloski, V.; Pecioski, D.; Anachkova, M.; Shishkovski, D.; Angjusheva Ignjatovska, A. Urban Sound Classification for IoT Devices in Smart City Infrastructures. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120517

Domazetovska Markovska S, Gavriloski V, Pecioski D, Anachkova M, Shishkovski D, Angjusheva Ignjatovska A. Urban Sound Classification for IoT Devices in Smart City Infrastructures. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):517. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120517

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomazetovska Markovska, Simona, Viktor Gavriloski, Damjan Pecioski, Maja Anachkova, Dejan Shishkovski, and Anastasija Angjusheva Ignjatovska. 2025. "Urban Sound Classification for IoT Devices in Smart City Infrastructures" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120517

APA StyleDomazetovska Markovska, S., Gavriloski, V., Pecioski, D., Anachkova, M., Shishkovski, D., & Angjusheva Ignjatovska, A. (2025). Urban Sound Classification for IoT Devices in Smart City Infrastructures. Urban Science, 9(12), 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120517