Assessing the Readiness for 15-Minute Cities: Spatial Analysis of Accessibility and Urban Sprawl in Limassol, Cyprus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Study: Limassol, Cyprus

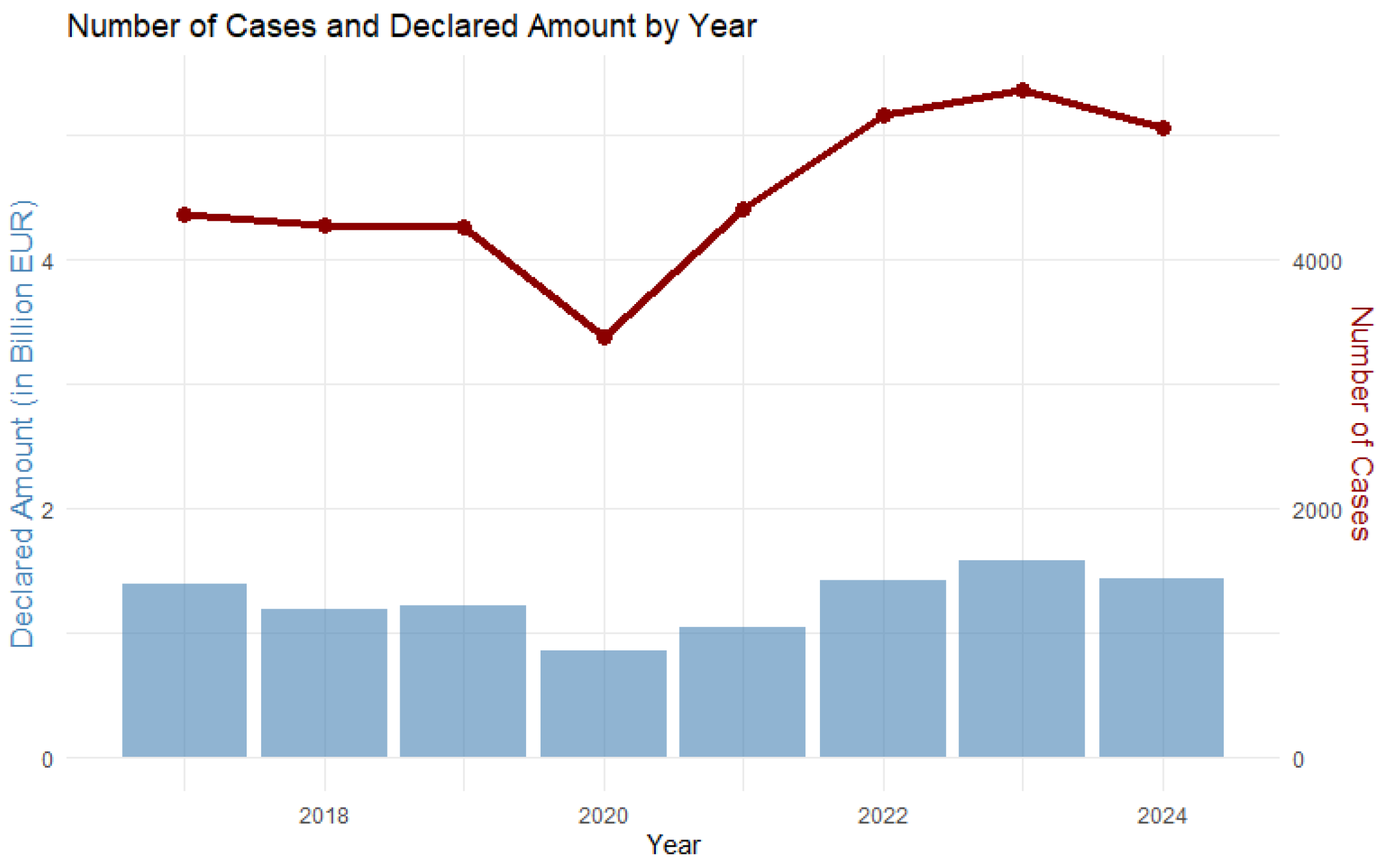

2.1. Unregulated Economic Growth

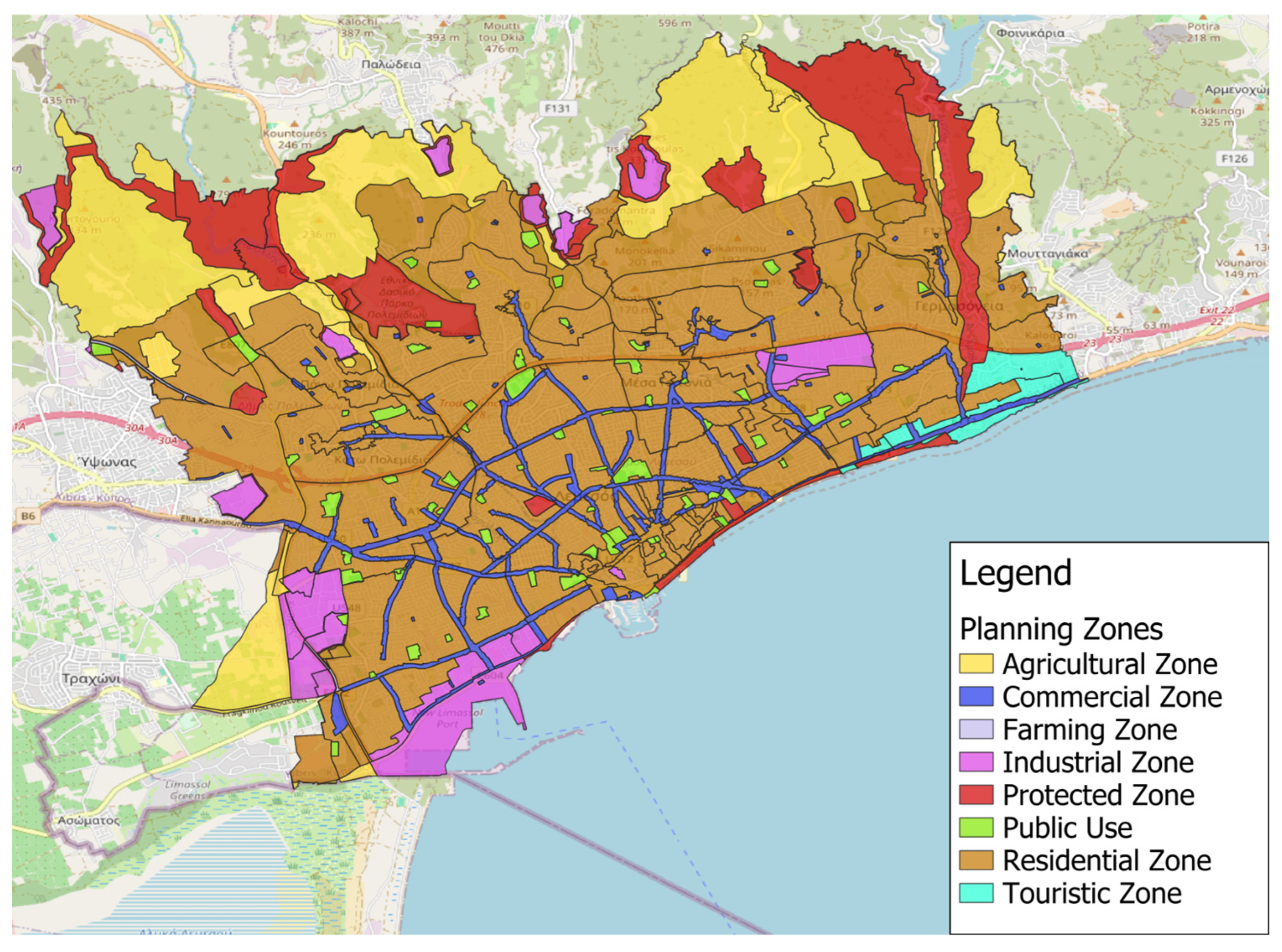

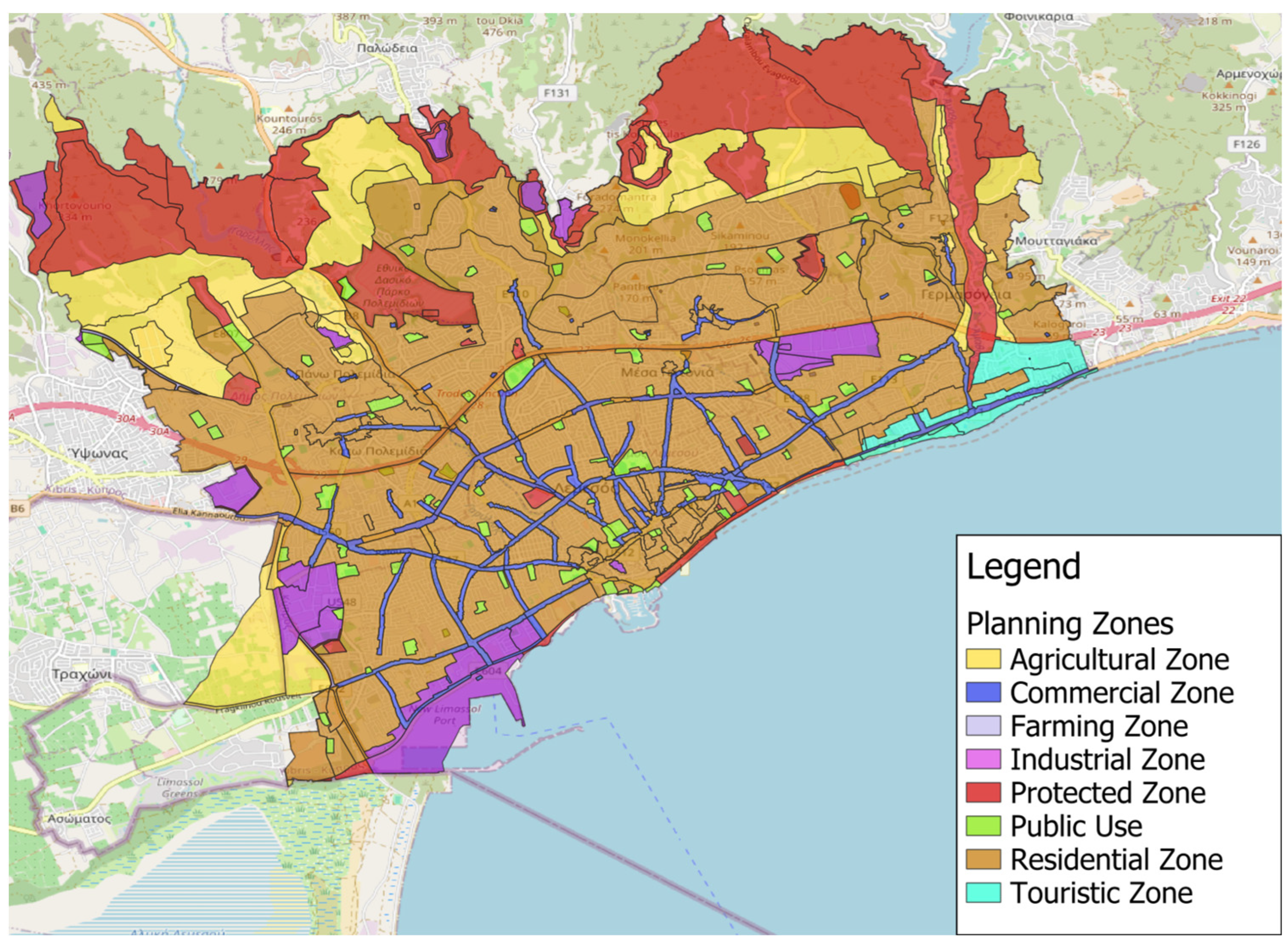

2.2. Planning Policies

2.3. Infrastructure

2.4. Social Functions

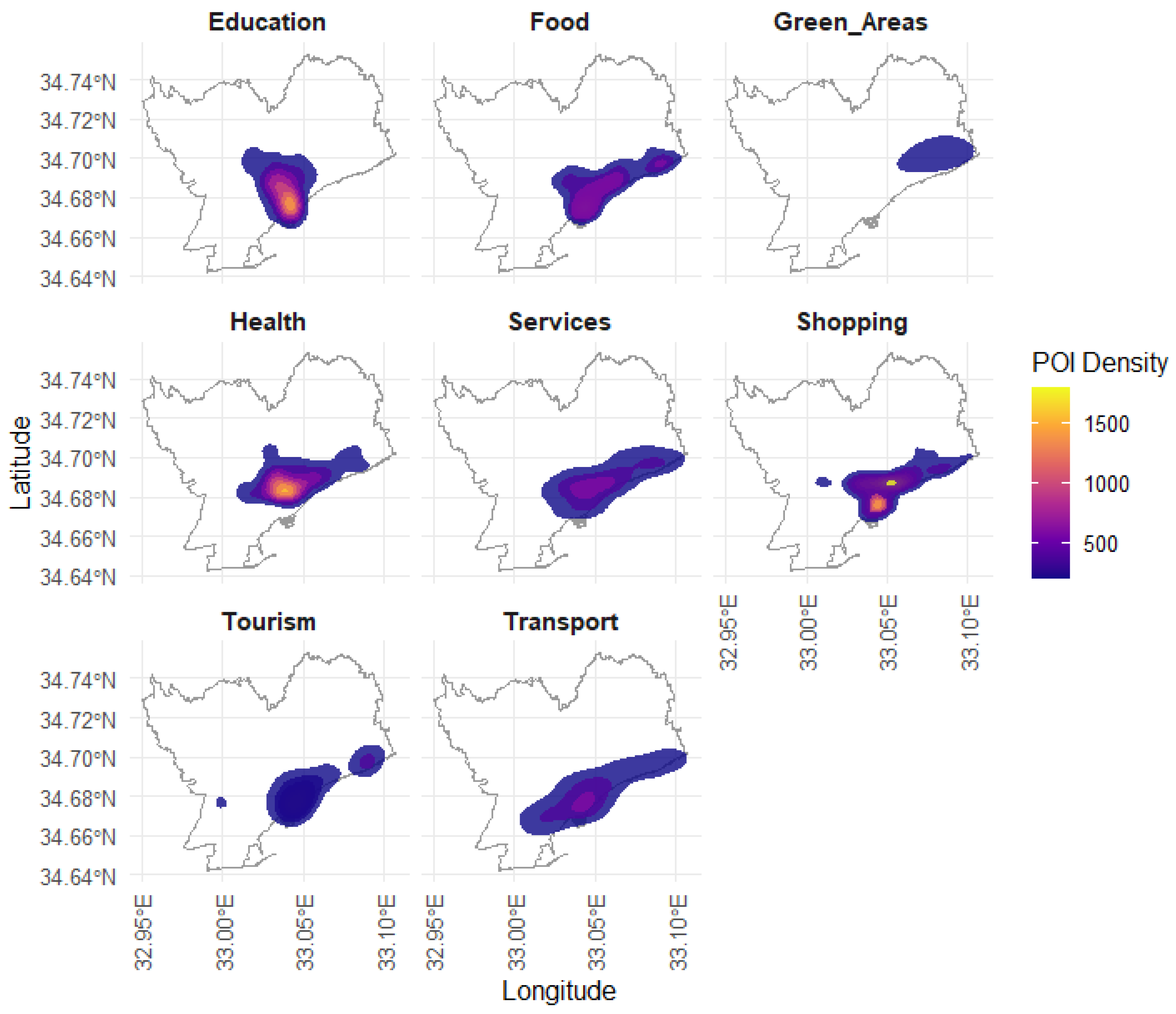

- Education (which includes colleges, kindergarten, libraries, schools, and universities);

- Food (which includes bakeries, bars, beverages, butchers, cafes, pubs, and supermarkets);

- Green Areas (which includes parks, dog parks, and camp sites);

- Health (which includes hospitals, clinics, dentists, doctors, pharmacies, and veterinary);

- Services (which includes banks and public authorities, e.g., post offices);

- Shopping (which includes bookshops, clothing retailers, furniture retailers, gift retailers, jewelry retailers, optician outlets, footwear retailers, sports equipment stores, and toy stores);

- Tourism (which includes hotels, museums, tourist information offices, hostels, guesthouses, and attractions);

- Transport (which includes bicycle and car rental and parking).

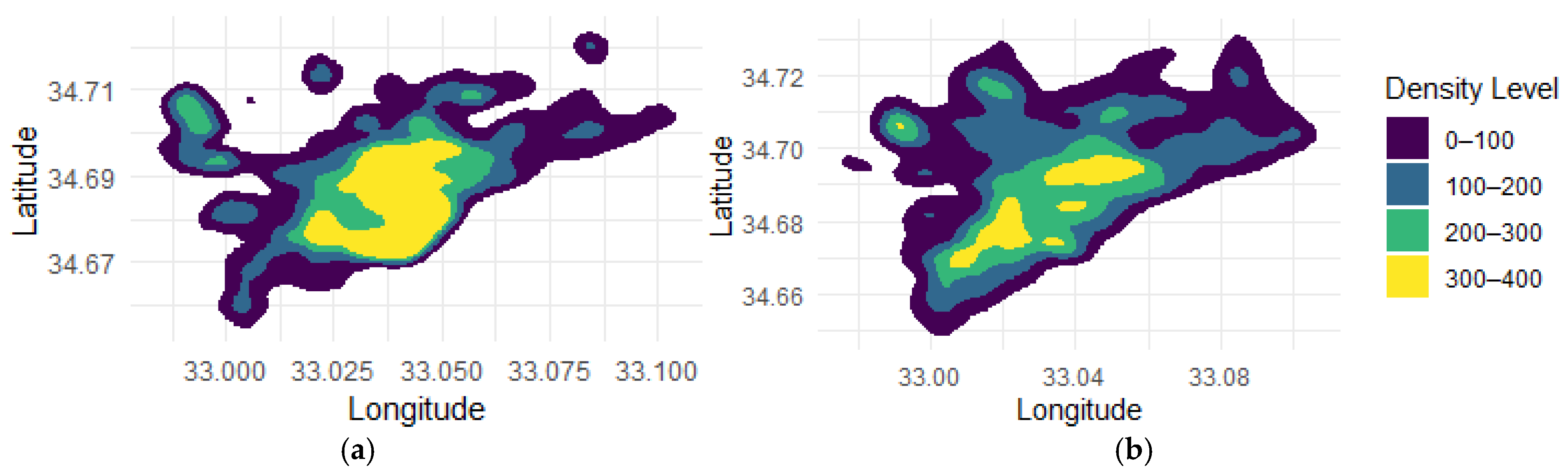

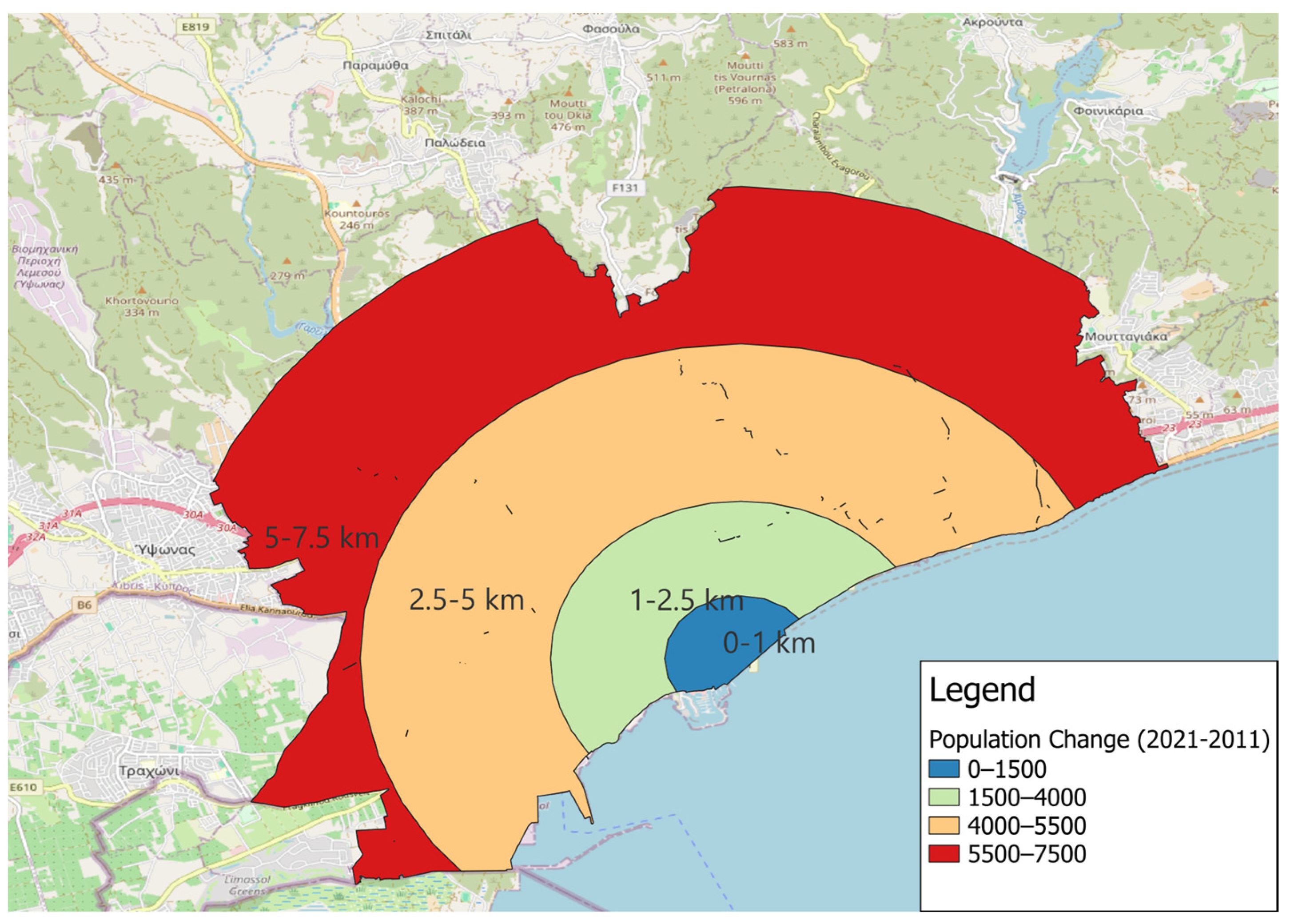

2.5. Population Distribution

3. Results

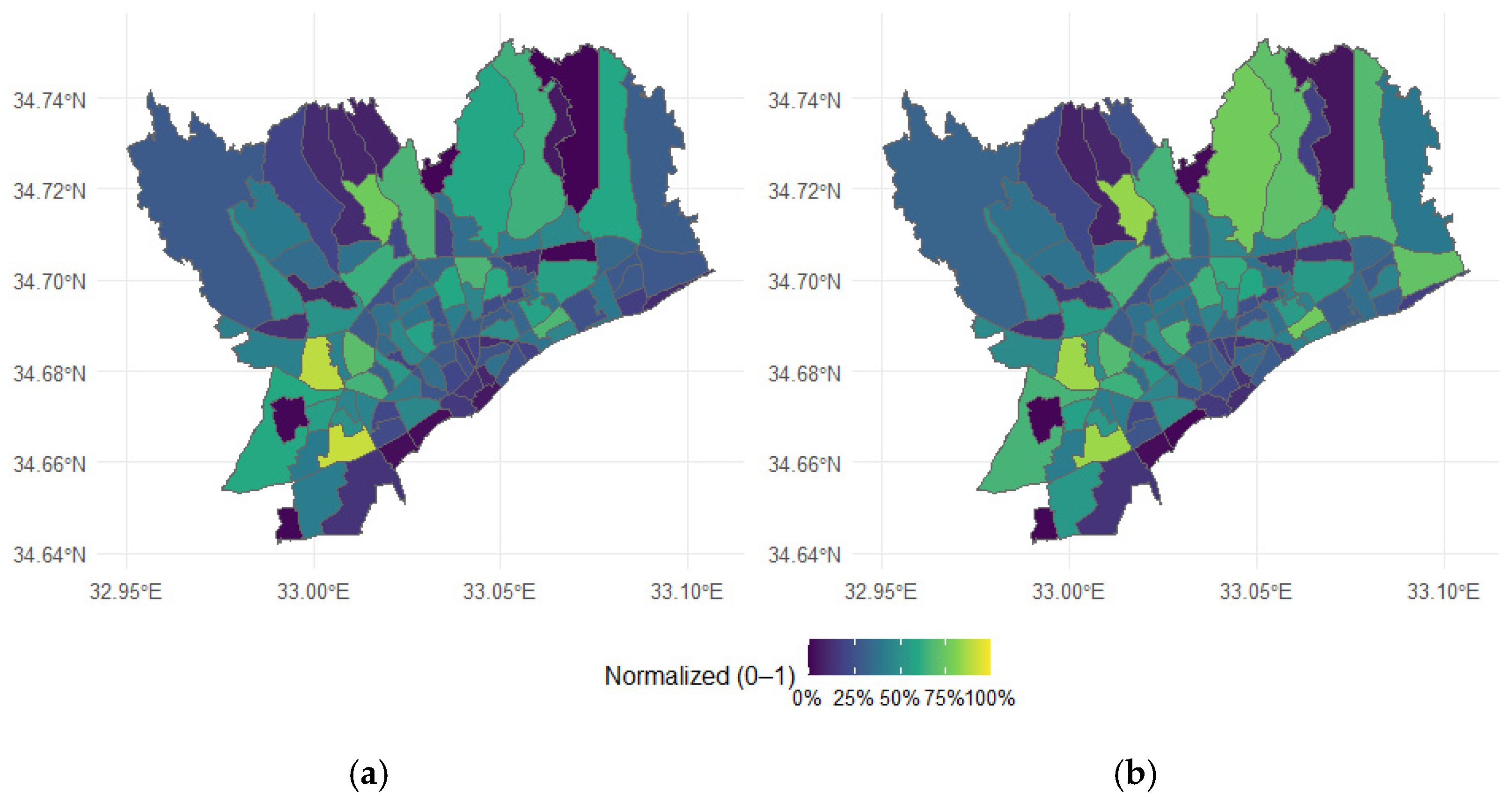

3.1. Urban Sprawl Index

- Size: spatial extent of urbanized areas (km2);

- Density: population per square kilometer of urbanized areas;

- Fragmentation: scattered development, as urbanized area patches grow in a dispersed manner; thus, the patch density is measured.

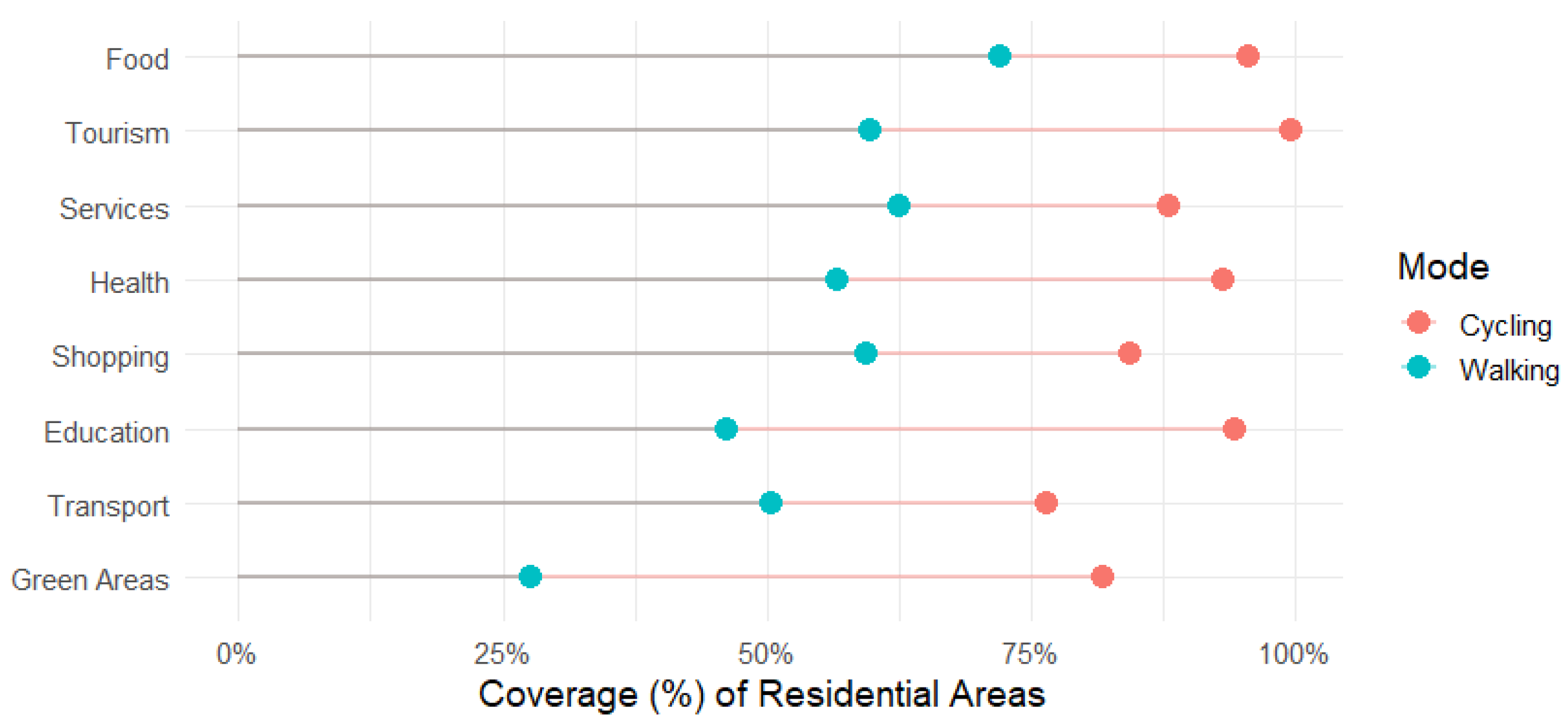

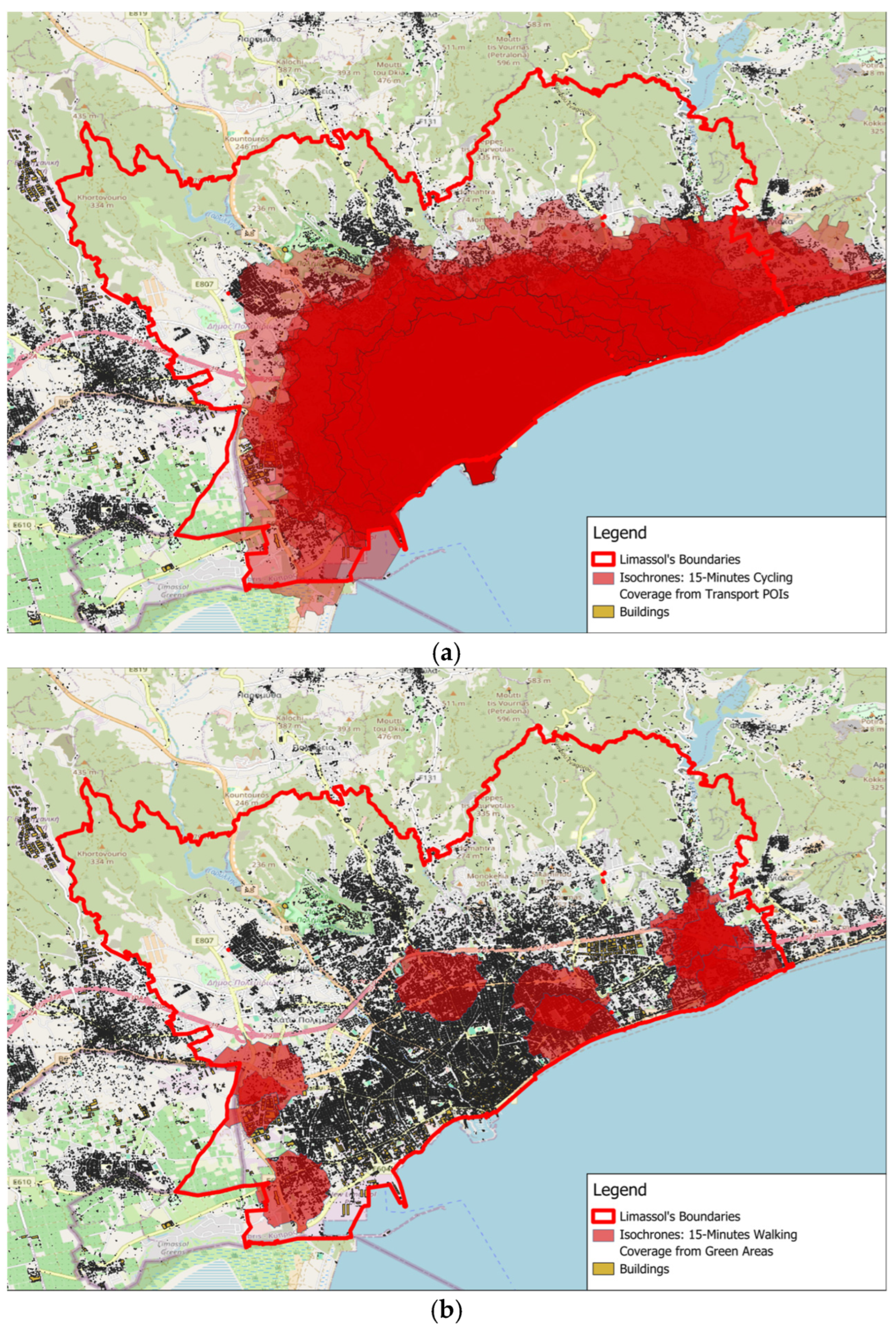

3.2. Walking and Cycling Isochrones

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN-Habitat. World Cities Report 2022. Envisaging the Future of Cities; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/06/wcr_2022.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2024; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–51. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2024/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2024.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- United Nations (n.d.). The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Yu, H.; Zhu, S.; Li, J.V.; Wang, L. Dynamics of urban sprawl: Deciphering the role of land prices and transportation costs in government-led urbanization. J. Urban Manag. 2024, 13, 736–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, K.; Jarallah Al-Zubaidi, A.M.; Qelichi, M.M.; Dolatkhahi, K. Un-derstanding urban sprawl in Baqubah, Iraq: A study of influential factors. J. Urban Manag. 2025, 14, 787–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, R.M. Urban Sprawl and Routing: A Comparative Study on 156 European Cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 253, 105205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Antipova, A. Structural equation model in exploring urban sprawl and its impact on commuting time in 162 US urbanized areas. Cities 2024, 148, 104855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, K.A.; Prasad, C.S.R.K. Impact of Urban Sprawl on Travel Demand for Public Transport, Private Transport and Walking. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 48, 1881–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Quantifying urban sprawl and investigating the cause-effect links among urban sprawl factors, commuting modes, and time: A case study of South Ko-rean cities. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 121, 104009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C. The Quarter-Hour City: For a New Chrono-Urban Planning. 2016. Available online: https://www.latribune.fr/regions/smart-cities/la-tribunede-carlos-moreno/la-ville-du-quart-d-heure-pour-un-nouveau-chronourbanisme-Allam604358.html (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Caprotti, F.; Duarte, C.; Joss, S. The 15-minute city as paranoid urbanism: Ten critical reflections. Cities 2024, 155, 105497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, D.; Szafrańska, E.; Korolko, M. The 15-minute city: Assumptions, opportunities and limitations. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2024, 66, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan-Horley, C.; Gibson, C.; Wolifson, P.; McGuirk, P.; Cook, N.; Warren, A. Lived experiences of the x-minute creative city: Front and back spaces of crea-tive work. Cities 2025, 162, 105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basbas, S.; Campisi, T.; Papas, T.; Trouva, M.; Tesoriere, G. The 15-Minute City Model: The Case of Sicily during and after COVID-19. Commun.-Sci. Lett. Univ. Zilina 2023, 25, A83–A92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papas, T.; Basbas, S.; Campisi, T. Urban mobility evolution and the 15-minute city model: From holistic to bottom-up approach. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostas Mouratidis. Time to challenge the 15-minute city: Seven pitfalls for sus-tainability, equity, livability, and spatial analysis. Cities 2024, 153, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Chuang, I.-T.; Qiao, W.; Jiang, J.; Beattie, L. Evaluating the 15-minute city paradigm across urban districts: A mobility-based approach in Hamil-ton, New Zealand. Cities 2024, 151, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, P.; Basbas, S. Urban Development and Transportation: Investi-gating Spatial Performance Indicators of 12 European Union Coastal Regions. Land 2023, 12, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the ‘15-Minute City’: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Jia, N.; Su, X.; Adams, M.D.; Deng, Y.; Ling, S. Assessing the ap-plicability of the 15-minute city: Insights from a spatial accessibility perspective. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 199, 104579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova-Antonova, D.; Murgante, B.; Malinov, S.; Nikolova, S.; Ilieva, S. Walkability analysis of Sofia’s neighborhoods powered by 15-minute city concept. Cities 2025, 165, 106171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, X.; Sun, T.; Ma, N.; Zhang, T. Compact urban morphology and the 15-minute city: Evidence from China. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 196, 104482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Q. ‘Bridge over troubled water’: Perceived accessibility prevents social exclusion in Chinese cities. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2025, 147, 104930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutcher, A.J.I.U. (n.d.). Is it Really the End for Cyprus’s Golden Passports? Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/10/16/is-this-really-the-end-for-cypruss-golden-passports (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- National Open Data Portal. 2025. Available online: https://www.data.gov.cy/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Abebe, F. Urban Sprawl and Its Implications on Land Use/Land Cover Dynamics: The Case Bahir Dar City. Ph.D. Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, B. Ageing in Suburban Neighbourhoods: Planning, Densities and Place Assessment. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razin, E. Policies to Control Urban Sprawl: Planning Regulations or Changes in the ‘Rules of the Game’? Urban Stud. 1998, 35, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenStreetMap Contributors. Planet Dump. 2015. Available online: https://planet.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Rahman, F.; Oliver, R.; Buehler, R.; Lee, J.; Crawford, T.; Kim, J. Impacts of point of interest (POI) data selection on 15-Minute City (15-MC) accessibility scores and inequality assessments. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 195, 104429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Service of Cyprus: Population Data. Available online: https://www.cystat.gov.cy/en/SubthemeStatistics?id=46 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Terzi, F.; Kaya, H.S. Dynamic spatial analysis of urban sprawl through fractal geometry: The case of Istanbul. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2011, 38, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoina, M.; Voukkali, I.; Anagnostopoulos, A.; Papamichael, I.; Stylianou, M.; Zorpas, A.A. The 15-minute city concept: The case study within a neighbour-hood of Thessaloniki. Waste Manag. Res. J. A Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2024, 42, 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolos, L. Evaluating Urban Sprawl Patterns through Fractal Analysis: The Case of Greek Metropolitan Areas and Issues of Sustainable Development. RePEc Res. Pap. Econ. 2008, 3, 53–77. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Meng, L. Patterns of Urban Sprawl from a Global Perspective. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 04020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Yoon, J.; Srikrishnan, V.; Daniel, B.; Judi, D. Landscape metrics regularly outperform other traditionally-used ancillary datasets in dasymetric mapping of population. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 99, 101899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greater Manchester Accessibility Levels (GMAL) Model. Available online: https://odata.tfgm.com/opendata/downloads/GMAL/GMAL%20Calculation%20Guide.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Active Mode Appraisal Toolkit User Guide. 2022. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/631744188fa8f50220e60d1a/active-model-appraisal-toolkit-user-guidance.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Bosina, E.; Weidmann, U. Estimating pedestrian speed using aggregated literature data. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2017, 468, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radics, M.; Panayotis Christidis Alonso, B.; dell’Olio, L. The X-Minute City: Analysing Accessibility to Essential Daily Destinations by Active Mobility in Seville. Land 2024, 13, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, T.; Farber, S.; Manaugh, K. Assessing the readiness for 15-minute cities: A literature review on performance metrics and implementation challenges worldwide. Transp. Rev. 2025, 45, 801–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elldér, E. Built environment and the evolution of the ‘15-minute city’: A 25-year longitudinal study of 200 Swedish cities. Cities 2024, 149, 104942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska, M.; Cubells, J.; Marquet, O. When proximity is not enough. A sociodemographic analysis of 15-minute city lifestyles. J. Urban Mobil. 2025, 7, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Bibri, S.E.; Jones, D.S.; Chabaud, D.; Moreno, C. Unpacking the ‘15-Minute City’ via 6G, IoT, and Digital Twins: Towards a New Narrative for Increas-ing Urban Efficiency, Resilience, and Sustainability. Sensors 2022, 22, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, J.F.; Silva, C.; Seisenberger, S.; Büttner, B.; McCormick, B.; Papa, E.; Cao, M. Classifying 15-minute Cities: A review of worldwide practices. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 189, 104234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Urbanized Areas (Based on the Planning Zones in 2006) | Urbanized Areas (Based on the Planning Zones in 2020) |

|---|---|---|

| Size | 51 km2 | 58 km2 |

| Density | 3505 people per km2 of urbanized area | 3627 people per km2 of urbanized area |

| Fragmentation | 0.49 | 0.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nikolaou, P.; Basbas, S.; Ioannou, B. Assessing the Readiness for 15-Minute Cities: Spatial Analysis of Accessibility and Urban Sprawl in Limassol, Cyprus. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120509

Nikolaou P, Basbas S, Ioannou B. Assessing the Readiness for 15-Minute Cities: Spatial Analysis of Accessibility and Urban Sprawl in Limassol, Cyprus. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):509. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120509

Chicago/Turabian StyleNikolaou, Paraskevas, Socrates Basbas, and Byron Ioannou. 2025. "Assessing the Readiness for 15-Minute Cities: Spatial Analysis of Accessibility and Urban Sprawl in Limassol, Cyprus" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120509

APA StyleNikolaou, P., Basbas, S., & Ioannou, B. (2025). Assessing the Readiness for 15-Minute Cities: Spatial Analysis of Accessibility and Urban Sprawl in Limassol, Cyprus. Urban Science, 9(12), 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120509