Evolving from Rules to Learning in Urban Modeling and Planning Support Systems

Abstract

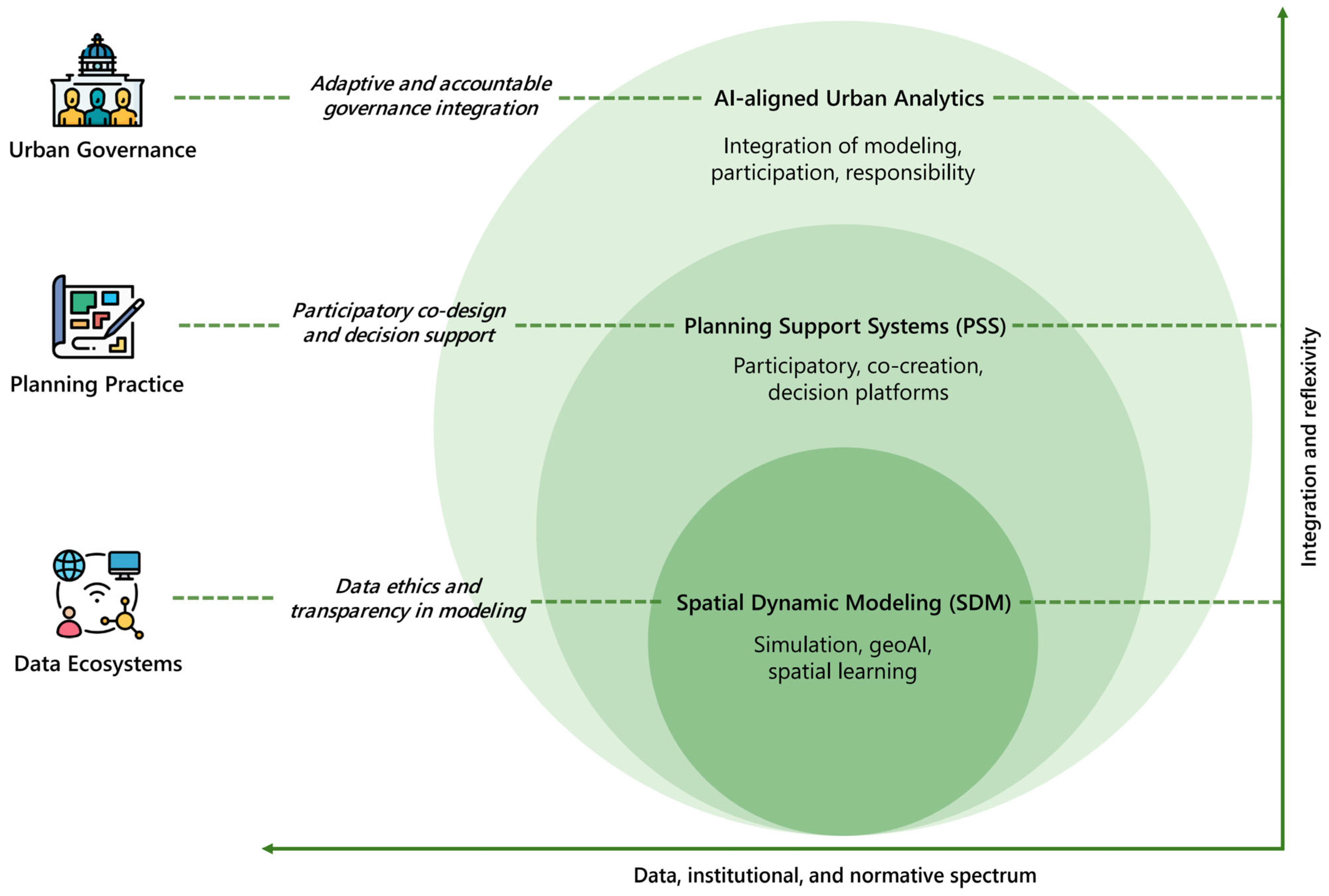

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Scope

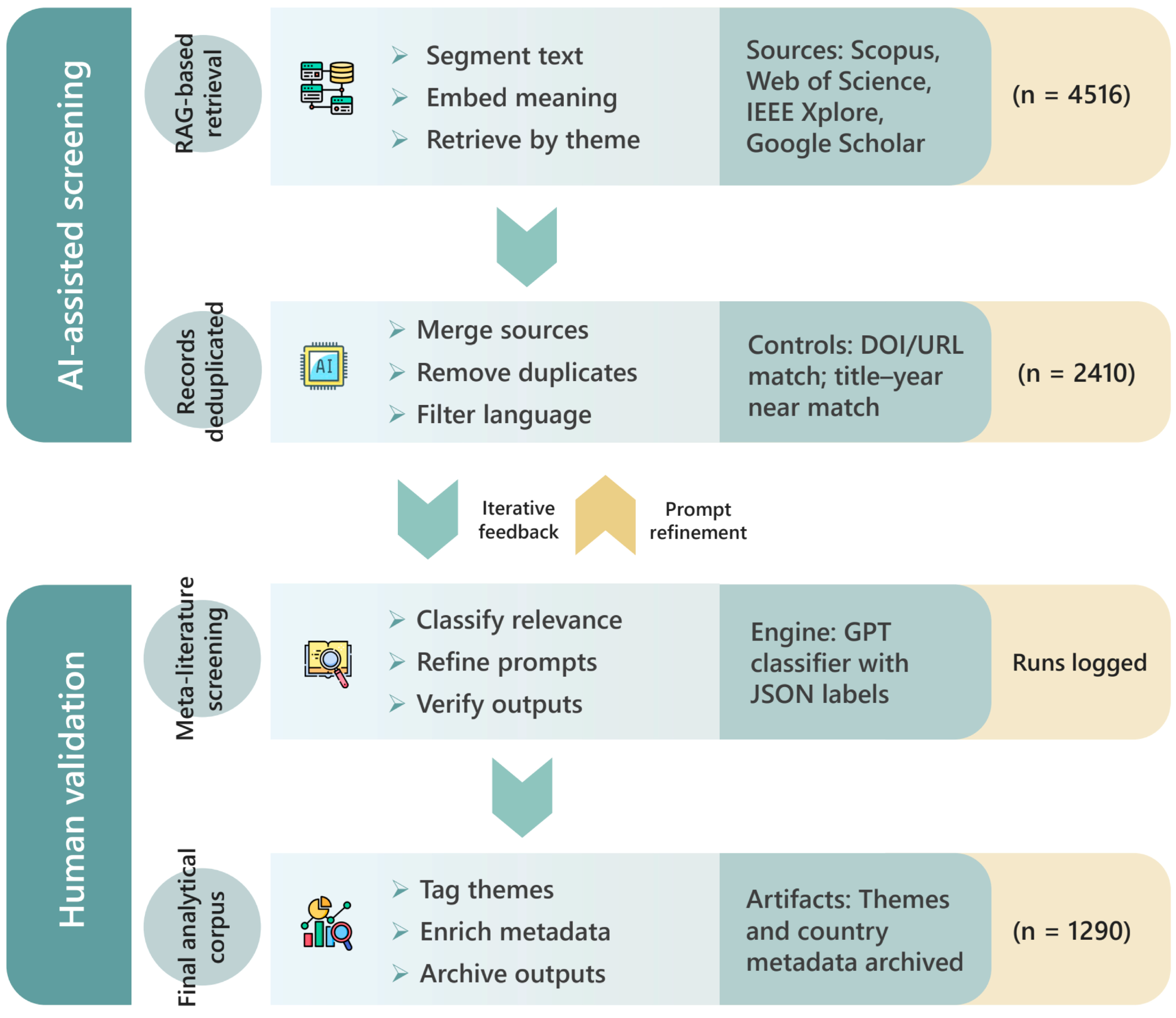

2.2. Data Harvesting and Cleaning

2.3. AI-Assisted Screening and Retrieval-Augmented Synthesis

2.4. Coding, Bibliometric Mapping, and Quality Assessment

3. Results

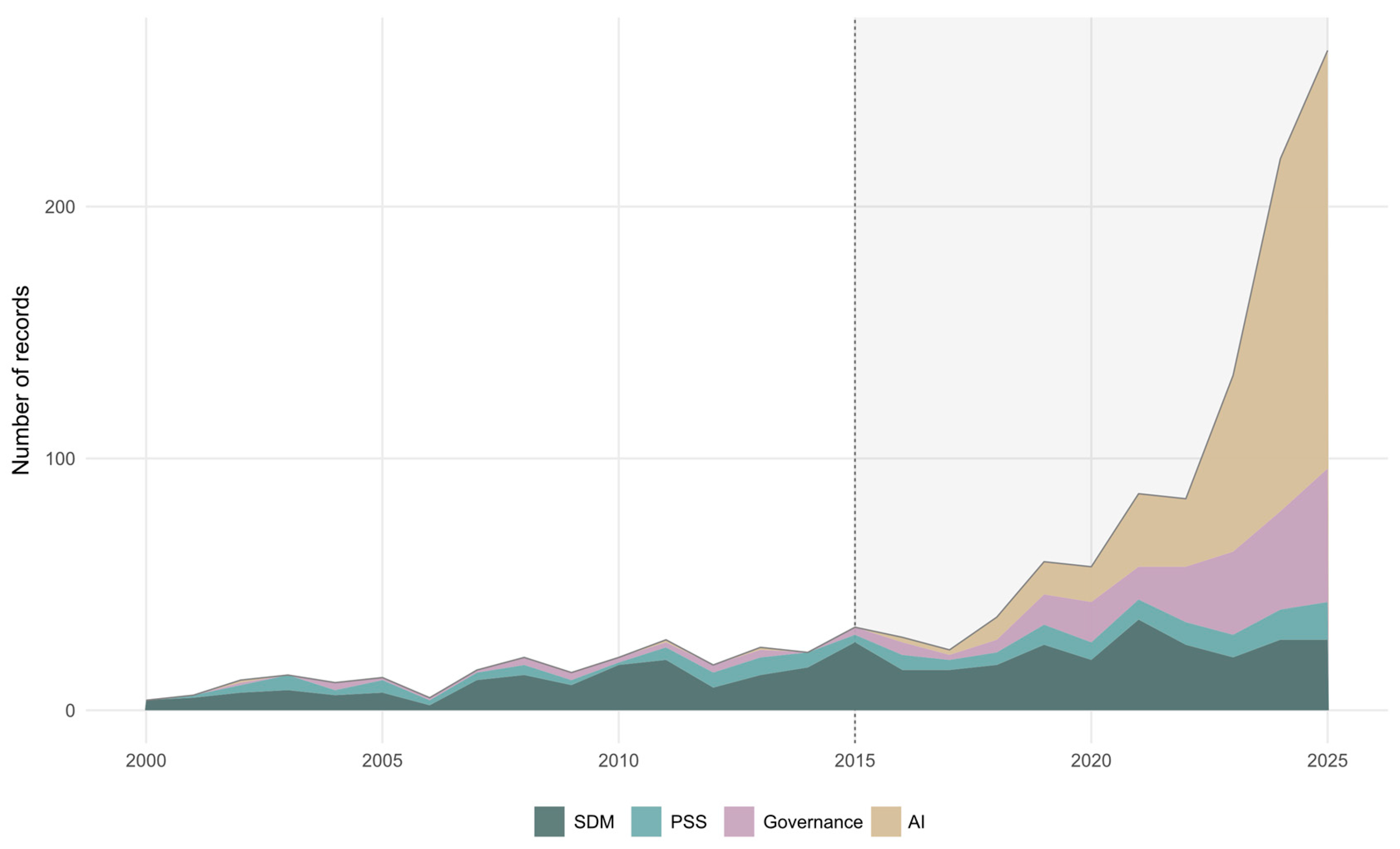

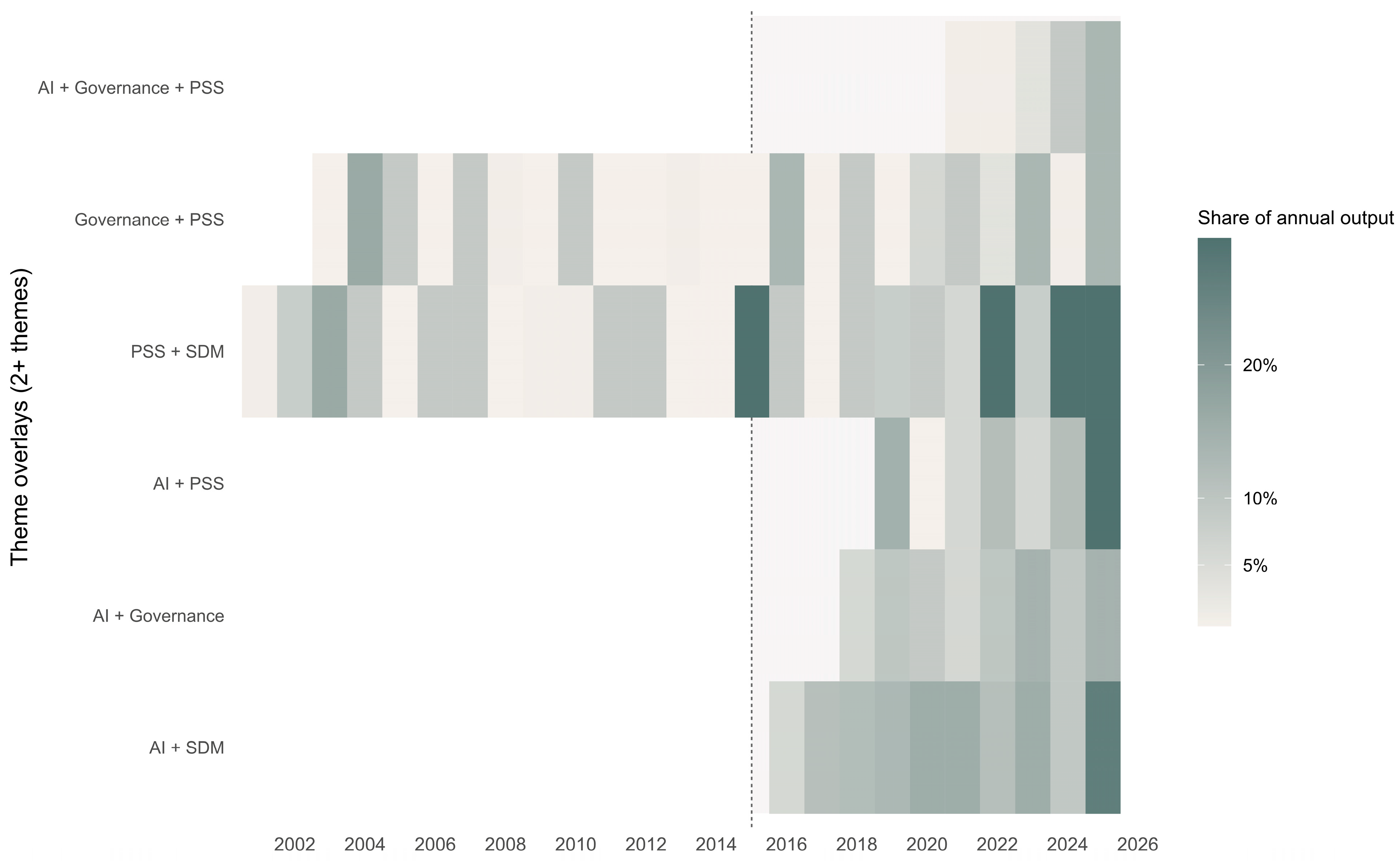

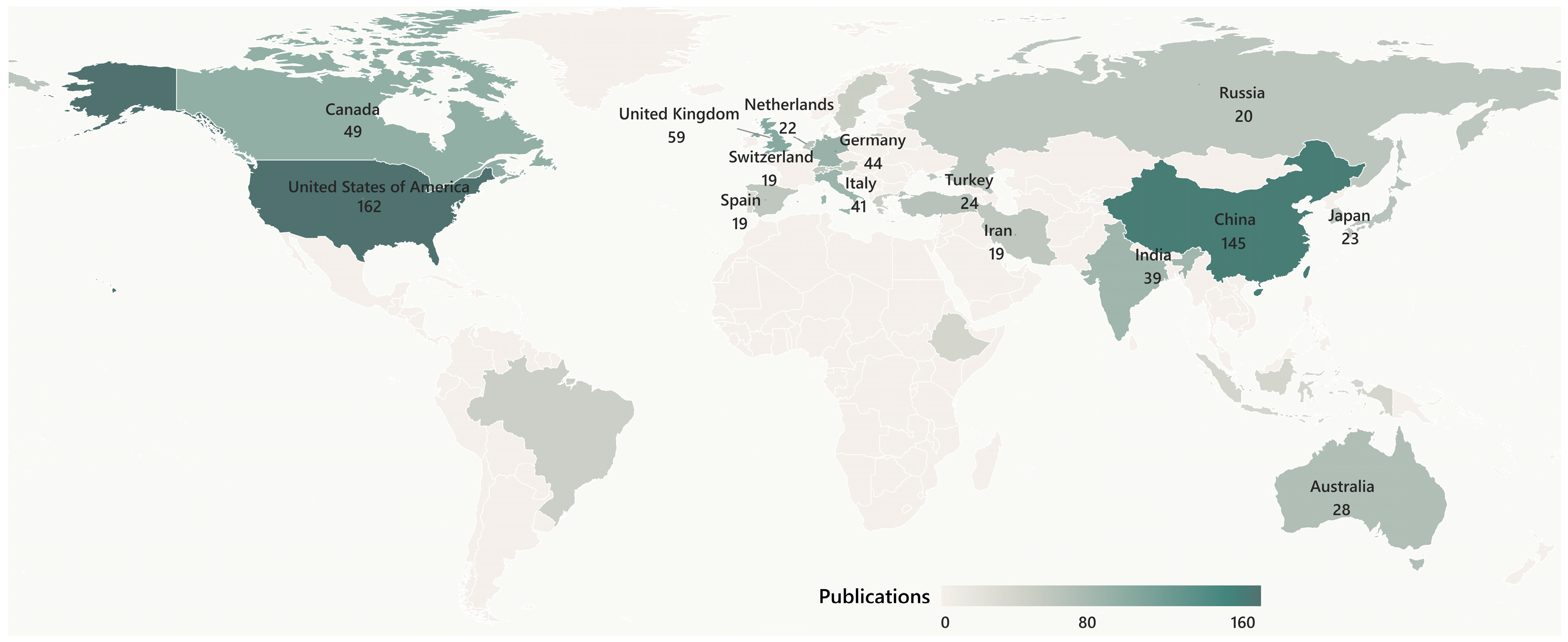

3.1. Overview of the Corpus and Cluster Composition

3.2. Evolution of SDM

3.3. The Transformation of PSSs

3.4. AI, Governance, and the Ethics of Urban Modeling

4. Discussion

4.1. Thematic Convergence of SDM, PSSs, and AI Governance

4.2. Toward Responsible Modeling

4.3. Research Agenda for AI-Aligned Urban Governance

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABM | Agent-Based Model |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CA | Cellular Automata |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| PSS | Planning Support System |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| SDM | Spatial Dynamic Modeling |

| VLM | Vision–Language Model |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Models, Endpoint, and Runtime Configuration

Appendix A.2. Tasks, Prompts, and JSON Schema

Appendix A.3. Evidence Packing, Domain Cues, and Pre-Tags

Appendix A.4. Batching, Timeouts, Parsing, and Retries

Appendix A.5. Inputs, Outputs, Determinism, and Run Artifacts

Appendix A.6. Corpus Provenance, Venue Levels, and Author Affiliations

References

- Bittencourt, J.C.N.; Costa, D.G.; Portugal, P.; Vasques, F. A Survey on Adaptive Smart Urban Systems. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 102826–102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. Urban Analytics; SAGE: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, A. Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Arundel, S.T.; Gao, S.; Goodchild, M.F.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zipf, A. GeoAI for Science and the Science of GeoAI. J. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wu, A.N.; Biljecki, F. Classification of Urban Morphology with Deep Learning: Application on Urban Vitality. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 90, 101706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Kwak, Y.; Cvetkovic, V.; Deal, B.; Mörtberg, U. Urban Spatial Dynamic Modeling Based on Urban Amenity Data to Inform Smart City Planning. Anthropocene 2023, 42, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Okada, N.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, P.; Zhang, J. Modeling Urban Expansion Scenarios by Coupling Cellular Automata and System Dynamics in Beijing, China. Appl. Geogr. 2006, 26, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Li, H.; Inohae, T.; Su, W.; Nagaie, T.; Hokao, K. Modeling Urban Land-Use Change by Integrating Cellular Automata and Markov Chains. Ecol. Model. 2011, 222, 3761–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsanjani, J.J.; Helbich, M.; Vaz, E.D.N. Spatiotemporal Simulation of Urban Growth Patterns Using Agent-Based Modeling: The Case of Tehran, Iran. Cities 2013, 32, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G.P. Reflections on the Foundations of System Dynamics. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2011, 27, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocabas, V.; Dragicevic, S. Bayesian Networks and Agent-Based Modeling Approach for Urban Land-Use and Population Density Change: A BNAS Model. J. Geogr. Syst. 2013, 15, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotson, T. Trial-and-error urbanism: Addressing obduracy, uncertainty and complexity in urban planning and design. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemak. Urban Sustain. 2015, 9, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Wang, B.; Cong, C.; Cvetkovic, V. Spatial Dynamic Modelling for Urban Scenario Planning: A Case Study of Nanjing, China. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 1380–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyebi, A.; Pijanowski, B.C.; Pekin, B. Two rule-based urban growth boundary models applied to the Tehran metropolitan area, Iran. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freni, G.; Mannina, G.; Viviani, G. Urban runoff modelling uncertainty: Comparison among Bayesian and pseudo-Bayesian methods. Environ. Model. Softw. 2009, 24, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Zhu, R.; Yang, J.; Meng, L. An Open-Source Framework of Generating Network-Based Transit Catchment Areas by Walking. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2020, 9, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova-Pozo, K.; Rouwette, E.A. Types of scenario planning and their effectiveness: A review of reviews. Futures 2023, 149, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Pang, C.; Xia, G.-S. Vision–Language Modeling Meets Remote Sensing: Models, datasets, and perspectives. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2025, 13, 276–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Chen, W.; Yan, Y.; Zhong, S.; Wang, K.; Wen, Q.; Liang, Y. UrbanVLP: Multi-Granularity Vision–Language Pretraining for Urban Socioeconomic Indicator Prediction. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 28061–28069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Huang, Q.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Z. Mixed land use measurement and mapping with street view images and spatial context-aware prompts via zero-shot multimodal learning. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 125, 103591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Biljecki, F. Explainable Spatially Explicit Geospatial Artificial Intelligence. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2024, 51, 1104–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Feng, T.; Safikhani, A.; Tepe, E. Enhancing Transparency in Land-Use Change Modeling: Leveraging Explainable AI Techniques for Urban Growth Prediction with Spatially Distributed Insights. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2025, 121, 102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sermet, Y.; Demir, I. GeospatialVR: A web-based virtual reality framework for collaborative environmental simulations. Comput. Geosci. 2022, 159, 105010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yue, J.; Wang, S.; Luo, Y.; Su, C.; Zhou, J.; Xu, D.; Lu, H. Development of Geographic Information System Architecture Feature Analysis and Evolution Trend Research. Sustainability 2024, 16, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertman, S.; Allan, A.; Pettit, C.; Stillwell, J. (Eds.) Planning Support Science for Smarter Urban Futures; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. Planning with Complexity: An Introduction to Collaborative Rationality for Public Policy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Forester, J. The Deliberative Practitioner: Encouraging Participatory Planning Processes; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Geertman, S.; Witte, P. Avoiding the Planning Support System Pitfalls? Lessons from the PSS Implementation Gap. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 1343–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lartey, D.; Law, K.M. Artificial intelligence adoption in urban planning governance: A systematic review of advancements in decision-making, and policy making. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 258, 105337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.; Wu, S.; Zaldivar, A.; Barnes, P.; Vasserman, L.; Hutchinson, B.; Spitzer, E.; Raji, I.D.; Gebru, T. Model Cards for Model Reporting. In Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Atlanta, GA, USA, 29–31 January 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, T.; Morgenstern, J.; Vecchione, B.; Vaughan, J.W.; Wallach, H.; Daumé, H., III; Crawford, K. Datasheets for Datasets. Commun. ACM 2021, 64, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, I.D.; Smart, A.; White, R.N.; Mitchell, M.; Gebru, T.; Hutchinson, B.; Smith-Loud, J.; Theron, D.; Barnes, P. Closing the AI Accountability Gap: Defining an End-to-End Framework for Internal Algorithmic Auditing. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Barcelona, Spain, 27–30 January 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, K.; Santos-Rodriguez, R.; Flach, P. FAT Forensics: A Python Toolbox for Algorithmic Fairness, Accountability and Transparency. Softw. Impacts 2022, 14, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badami, A.A. Management of the image of the city in urban planning: Experimental methodologies in the colour plan of the Egadi Islands. Urban Des. Int. 2025, 30, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobin, A.; Ienca, M.; Vayena, E. The Global Landscape of AI Ethics Guidelines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Goodchild, M.; Huang, X.; Li, W.; Shaw, S.L.; Newman, G. Artificial intelligence in urban science: Why does it matter? Ann. GIS 2025, 31, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugere, C.; Bansal, T.; Kruijssen, F.; Williams, M. Humanizing aquaculture development: Putting social and human concerns at the center of future aquaculture development. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2023, 54, 482–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrabi, H.; Doost Mohammadian, M.R. Fusion of Digital Twin, Internet-of-Things and Artificial Intelligence for Urban Intelligence. In Digital Twin Computing for Urban Intelligence; Pourroostaei Ardakani, S., Cheshmehzangi, A., Eds.; Urban Sustainability; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechesov, A.; Dorokhov, I.; Ruponen, J. Virtual Cities: From Digital Twins to Autonomous AI Societies. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 13866–13903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pröbstl, F.; Paulsch, A.; Zedda, L.; Nöske, N.; Santos, E.M.C.; Zinngrebe, Y. Biodiversity policy integration in five policy sectors in Germany: How can we transform governance to make implementation work? Earth Syst. Gov. 2023, 16, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, D.W.; Clark, W.C.; Alcock, F.; Dickson, N.M.; Eckley, N.; Guston, D.H.; Jäger, J.; Mitchell, R.B. Knowledge Systems for Sustainable Development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8086–8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stilgoe, J.; Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P. Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miake-Lye, I.M.; Hempel, S.; Shanman, R.; Shekelle, P.G. What Is an Evidence Map? A Systematic Review of Published Evidence Maps and Their Definitions, Methods, and Products. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallings, J.; Vance, E.; Yang, J.; Vannier, M.W.; Liang, J.; Pang, L.; Dai, L.; Ye, I.; Wang, G. Determining scientific impact using a collaboration index. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9680–9685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennstädt, F.; Zink, J.; Putora, P.M.; Hastings, J.; Cihoric, N. Title and abstract screening for literature reviews using large language models: An exploratory study in the biomedical domain. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, J.; Tan, X. Evaluating the effectiveness of large language models in abstract screening: A comparative analysis. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohan, A.; Feldman, S.; Beltagy, I.; Downey, D.; Weld, D.S. SPECTER: Document-Level Representation Learning Using Citation-Informed Transformers. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 2270–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, R.; Riley, V. Humans and Automation: Use, Misuse, Disuse, Abuse. Hum. Factors 1997, 39, 230–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skitka, L.J.; Mosier, K.L.; Burdick, M.D. Does Automation Bias Decision-Making? Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 1999, 51, 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, K.; Roudsari, A.; Wyatt, J.C. Automation Bias: A Systematic Review of Frequency, Effect Mediators, and Mitigators. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2012, 19, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, I.; Torrens, P. Geosimulation: Automata-Based Modeling of Urban Phenomena; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Herold, M.; Couclelis, H.; Clarke, K.C. The role of spatial metrics in the analysis and modeling of urban land use change. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2005, 29, 369–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanilov, K. Accessibility and land use: The case of suburban Seattle, 1960–1990. Reg. Stud. 2003, 37, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppenstall, A.; Crooks, A.; See, L.; Batty, M. (Eds.) Agent-Based Models of Geographical Systems; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macal, C.M.; North, M.J. Tutorial on Agent-Based Modeling and Simulation. J. Simul. 2010, 4, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontius, R.G., Jr.; Millones, M. Death to Kappa: Birth of Quantity Disagreement and Allocation Disagreement for Accuracy Assessment. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 32, 4407–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Calibration of stochastic cellular automata: The application to rural–urban land conversions. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2002, 16, 795–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, C.; Pettit, C. Charting the Past and Possible Futures of Planning Support Systems: Results of a Citation Network Analysis. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2022, 49, 1875–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.X.; Tuia, D.; Mou, L.; Xia, G.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Fraundorfer, F. Deep Learning in Remote Sensing: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2017, 5, 8–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, Y.; Yin, G.; Johnson, B.A. Deep Learning in Remote Sensing Applications: A Meta-Analysis and Review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 152, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedano, F.; Kempeneers, P.; Strobl, P.; Kucera, J.; Vogt, P.; Seebach, L.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J. A cloud mask methodology for high-resolution remote sensing data combining information from high and medium resolution optical sensors. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2011, 66, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chen, D.; Guan, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, J.; Ye, Q.; Fu, L.; Zhou, J. RemoteCLIP: A Vision–Language Foundation Model for Remote Sensing. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.11029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why Should I Trust You?”: Explaining Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’16), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4765–4774. [Google Scholar]

- Tuia, D.; Persello, C.; Bruzzone, L. Domain Adaptation for the Classification of Remote Sensing Data: An Overview of Recent Advances. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2016, 4, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Camps-Valls, G.; Stevens, B.; Jung, M.; Denzler, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Prabhat, F. Deep Learning and Process Understanding for Data-Driven Earth System Science. Nature 2019, 566, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brail, R.; Klosterman, R. (Eds.) Planning Support Systems; ESRI Press: Redlands, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Geertman, S.; Stillwell, J. (Eds.) Planning Support Systems: Best Practice and New Methods; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barredo, J.I.; Kasanko, M.; McCormick, N.; Lavalle, C. Modelling dynamic spatial processes: Simulation of urban future scenarios through cellular automata. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 64, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Star, S.L.; Griesemer, J.R. Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–1939. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1989, 19, 387–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haklay, M. How Good Is Volunteered Geographical Information? A Comparative Study of OpenStreetMap and Ordnance Survey Datasets. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2010, 37, 682–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Charalabidis, Y.; Zuiderwijk, A. Benefits, Adoption Barriers and Myths of Open Data and Open Government. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2012, 29, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linders, D. Towards open development: Leveraging open data to improve the planning and coordination of international aid. Gov. Inf. Q. 2013, 30, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F. Citizens as Sensors: The World of Volunteered Geography. GeoJournal 2007, 69, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel Boulos, M.N.; Resch, B.; Crowley, D.N.; Breslin, J.G.; Sohn, G.; Burtner, E.R.; Pike, W.A.; Jezierski, E.; Chuang, K.-Y.S. Crowdsourcing, citizen sensing and sensor web technologies for public and environmental health surveillance and crisis management: Trends, OGC standards and application examples. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2011, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malczewski, J.; Rinner, C. Multicriteria Decision Analysis in Geographic Information Science; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, M.; Van Kleek, M.; Binns, R. Fairness and Accountability Design Needs for Algorithmic Support in High-Stakes Public Sector Decision-Making. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinov, A.; Bousquet, F. Modelling with Stakeholders. Environ. Model. Softw. 2010, 25, 1268–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ignazio, C.; Klein, L.F. Data Feminism; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Pantyley, V.; Blaszke, M.; Fakeyeva, L.; Lozynskyy, R.; Petrisor, A.-I. Spatial planning at the national level: Comparison of legal and strategic instruments in a case study of Belarus, Ukraine, and Poland. Land 2023, 12, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plann. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0); NIST AI 100-1; U.S. Department of Commerce: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/nist.ai.100-1.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Arnold, M.; Bellamy, R.; Hind, M.; Houde, S.; Mehta, S.; Mojsilović, A.; Nair, R.; Ramamurthy, K.N.; Olteanu, A.; Piorkowski, D.; et al. FactSheets: Increasing Trust in AI Services through Supplier’s Declarations of Conformity. IBM J. Res. Dev. 2020, 64, 6:1–6:13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, R.; Monreale, A.; Ruggieri, S.; Turini, F.; Giannotti, F.; Pedreschi, D. A Survey of Methods for Explaining Black Box Models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, N.; Morstatter, F.; Saxena, N.; Lerman, K.; Galstyan, A. A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Fang, C. Remote Sensing with Spatial Big Data: A Review and Renewed Perspective of Urban Studies in Recent Decades. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiran, F.; Calders, T. Data Preprocessing Techniques for Classification without Discrimination. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2012, 33, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.B.; Valera, I.; Rodriguez, M.G.; Gummadi, K.P. Fairness Beyond Disparate Treatment & Impact: Learning Classification without Disparate Mistreatment. In Proceedings of the 26th International World Wide Web Conference, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 1171–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodspeed, R. Scenario Planning for Cities and Regions: Managing Uncertainty, Complexity, and Change; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brabham, D.C. Crowdsourcing the Public Participation Process for Planning Projects. Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence; OECD/LEGAL/0449; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission High-Level Expert Group on AI. Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, B.; Brown, J.M.; Han, B.; Herman, B.; Weber, N.; Yan, A.; Yang, S.; Yang, Y. Integrative Urban AI to Expand Coverage, Access, and Equity of Urban Data. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2022, 231, 1741–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amershi, S.; Weld, D.; Vorvoreanu, M.; Fourney, A.; Nushi, B.; Collisson, P.; Suh, J.; Iqbal, S.; Bennett, P.N.; Inkpen, K.; et al. Guidelines for Human–AI Interaction. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Voß, J.-P.; Bauknecht, D.; Kemp, R. (Eds.) Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Malczewski, J. GIS and Multicriteria Decision Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zellner, M.L. Participatory modeling for collaborative landscape and environmental planning: From potential to realization. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 247, 105063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2017), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, E.M.; Friedman, B. Data Statements for Natural Language Processing: Toward Mitigating System Bias and Enabling Better Science. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2018, 6, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L.; Cowls, J.; Beltrametti, M.; Chatila, R.; Chazerand, P.; Dignum, V.; Luetge, C.; Madelin, R.; Pagallo, U.; Rossi, F.; et al. AI4People—An Ethical Framework for a Good AI Society: Opportunities, Risks, Principles, and Recommendations. Minds Mach. 2018, 28, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpatne, A.; Atluri, G.; Faghmous, J.H.; Steinbach, M.; Banerjee, A.; Ganguly, A.; Shekhar, S.; Samatova, N.; Kumar, V. Theory-Guided Data Science: A New Paradigm for Scientific Discovery. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2017, 29, 2318–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Page, J.; Cvetkovic, V. Urban Ecosystem Vulnerability Assessment to Support Climate-Resilient City Development. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaei, M.; Salar, Y.S.; Zwierzchowska, I.; Azinmoghaddam, F.; Hof, A. Exploring inequality in green space accessibility for women-Evidence from Mashhad, Iran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 126, 106406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, S.; Naghshineh, R.; Ahmadian, A. Determine of Proxemic Distance Changes before and During COVID-19 Pandemic with Cognitive Science Approach. PsyArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröger, G.; Plümer, L. CityGML—Interoperable Semantic 3D City Models. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2012, 71, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funtowicz, S.O.; Ravetz, J.R. Science for the Post-Normal Age. Futures 1993, 25, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemmer, K.; Rolf, E.; Robinson, C.; Mackey, L.; Rußwurm, M. SatCLIP: Global, General-Purpose Location Embeddings with Satellite Imagery. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 4347–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Guo, Y.; Yin, J. RS5M and GeoRSCLIP: A Large Scale Vision–Language Dataset and a Large Vision–Language Model for Remote Sensing. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.11300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | Representative Keywords |

|---|---|

| Modeling approaches | spatial dynamic modeling; cellular automata; agent-based model; hybrid modeling; system dynamics; Markov chain urban modeling |

| Urban simulation and planning applications | urban growth simulation; urban expansion modeling; urban land change modeling; urban functional typologies; fine-grained urban modeling |

| Decision-support and planning tools | planning support system; decision support framework; urban analytics platform; urban scenario modeling; participatory planning tools |

| AI and advanced data integration | urban AI; vision–language model; deep learning urban modeling; machine learning urban dynamics; digital twins; urban big data analytics; GeoAI; generative AI for planning |

| Ethics, inclusivity, and governance | inclusive urban modeling; data justice; algorithmic fairness; AI governance; digital inclusion; citizen-centric urban AI; urban digital rights |

| Dimension | Representative Attributes and Description |

|---|---|

| Model family | CA, ABM, hybrid models integrating Markov or system-dynamics components, deep learning or GeoAI models, VLM, and digital twin frameworks. |

| Application domain | Urban growth and expansion modeling, accessibility or mobility studies, functional or morphological mapping, climate resilience assessment, and other spatial planning applications. |

| PSS role | Software prototype, analytical platform, participatory decision-support interface, or integrated scenario engine linking simulation with stakeholder interaction. |

| Validation approach | Use of performance metrics such as FoM, Kappa, or F1 score, cross-scale or temporal transfer tests, sensitivity analyses, and external benchmark comparisons. |

| Governance and inclusion | Presence of fairness audits, stakeholder participation, transparency protocols, data rights frameworks, or explicit discussion of ethical AI and inclusion. |

| Openness and reproducibility | Availability of open data, public code repositories, model documentation, or Supplementary Materials facilitating replication. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, Z. Evolving from Rules to Learning in Urban Modeling and Planning Support Systems. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120508

Cai Z. Evolving from Rules to Learning in Urban Modeling and Planning Support Systems. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):508. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120508

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Zipan. 2025. "Evolving from Rules to Learning in Urban Modeling and Planning Support Systems" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120508

APA StyleCai, Z. (2025). Evolving from Rules to Learning in Urban Modeling and Planning Support Systems. Urban Science, 9(12), 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120508