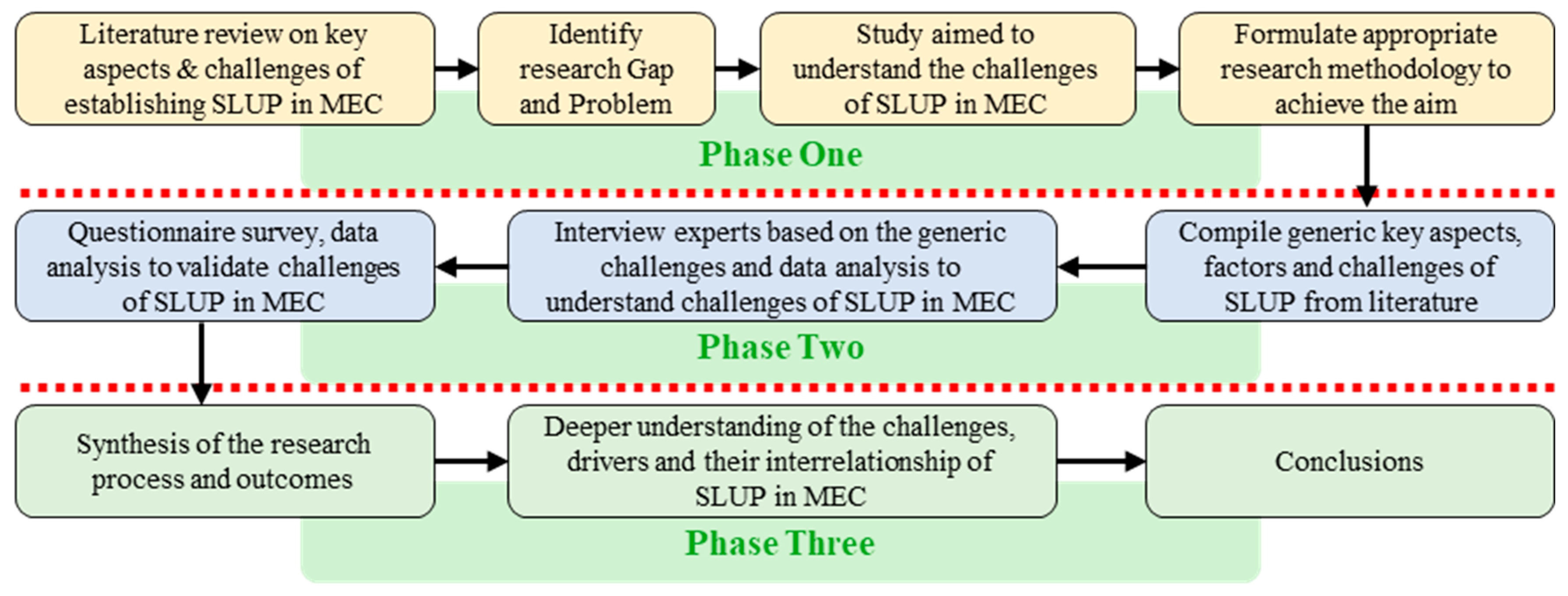

4.1. Data Analysis of the In-Depth Interviews and Developing a Framework to Understand the Challenges

Experts shared the lessons that they had learned from projects designing SLUPs. Their collective insights underscore the critical importance of integrating community engagement, climate-conscious design, efficient resource use, and ongoing evaluation in creating urban community parks. The interviewees were asked to state the challenges in establishing SLUPs in MECs. Experts A and C–S identified development funds and governance as key issues, besides the need for sufficient financial resources and effective management frameworks. Experts B–E and J highlighted the harsh climate of the arid region as a significant obstacle, along with the high costs of implementing sustainable features, such as advanced irrigation systems and shading structures. Experts F, S, and T highlighted funding and resource limitations as major constraints. Experts E–R raised concerns about the high costs associated with sustainable materials and technologies, the limited availability of native plants suitable for the local climate, water scarcity for irrigation, the creation of shaded areas to combat heat, and the design of flexible spaces that can adapt to evolving community needs. Other challenges included the resistance to changes in traditional park designs and the difficulty of balancing aesthetic appeal with sustainability goals in a hot urban environment.

Experts C–E, G–I, and M–Q criticized top-down strategies for often neglecting community input, emphasizing the importance of involving residents in the design process to ensure that parks fulfill their actual needs, preferences, sense of ownership, and responsibility. They recommended methods such as surveys, workshops, and focus groups to identify local needs and preferences, ensuring that the park reflects community values. Notably, the challenge associated with engaging residents during the design, management, and maintenance processes was specifically mentioned by over 60% of the interviewees, which was not found among the challenges collated in

Table 3. Experts G–I and L–T noted that insufficient funding and inadequate maintenance quality could hinder effective park management. They also emphasized that the lack of public awareness might limit community engagement and suggested that municipalities should focus on initiatives to enhance funding opportunities and improve maintenance practices. Experts D and G–J emphasized the importance of public awareness and education about sustainability practices, particularly among government officials who, instead of recognizing the benefits of sustainable strategies, may be hesitant to adopt them.

According to Experts A, C, and I–P, lack of maintenance poses an ongoing challenge (e.g., cleanliness, proper lighting to ensure the park’s safety). They stated that integrating smart technologies can be problematic because of the lack of robust infrastructure and public awareness, particularly among older community members who may be unfamiliar with these innovations. Experts K–P highlighted the need for proper coordination between hardscape and softscape elements to achieve cohesive and functional park designs. Expert L summarized the key challenges, including managing the hot climate, ensuring efficient water usage, balancing budget constraints, integrating eco-friendly materials, and engaging the community throughout the park’s lifecycle. Experts I–M added that climate change could affect the effectiveness of current design strategies, emphasizing the importance of planning for adaptability and resilience in the SLUP design.

Experts C–H highlighted the need for user-friendly and accessible technological solutions. Experts F–P underscored the importance of monitoring and evaluation through feedback mechanisms to assess the effectiveness of park design and amenities. Experts A, C, D, and I–L emphasized that the built environment encompasses not only physical aspects but also socio-cultural factors that influence how people perceive and use space. Understanding these elements is critical for creating parks that meet community needs and for maintaining open communication with users throughout the development process. Experts D, L, and R advocated a top-down approach to sustainability initiatives, asserting that leaders and government officials must drive the transformation of parks into sustainable spaces. Delegating this responsibility solely to the community, they warned, could lead to uncertainty and delays in finding effective solutions to the SLUP.

Experts A–D and J–O highlighted the benefits of utilizing local resources and materials, such as local stone, which are often better suited to regional climates. Experts provided valuable insights into designing parks in MECs that align with the region’s unique climate and cultural identity. Their collective insights emphasized the importance of integrating climate adaptability, cultural sensitivity, and community engagement in park designs, ensuring they meet environmental goals while enriching the social fabric of MECs. Experts were specifically asked how the incorporation of smart technologies would enhance the efficiency of SLUPs. Experts anonymously agreed that integrating smart technologies is beneficial for both operational efficiency and user experience. The experts’ insights into the challenges are summarized in

Figure 2.

Experts were asked to elaborate on how to overcome the challenges for the successful establishment of SLUPs in MECs. All experts contributed various recommendations or enablers that would help tackle the challenge of implementing SLUPs in MECs. The key enablers drawn from the experts’ insights are:

Interdisciplinary collaboration among all professionals is essential.

Community involvement throughout the design, implementation, and maintenance processes.

Clear vision and goals for sustainability, biodiversity, and community engagement are required.

Maintenance plan.

Monitoring and adaptation.

Adequate funding and resources from public and private sources.

Education and awareness.

Balance between smart technology and sustainable practices—technology should support, not overshadow, environmental goals.

Enforcing regulations to safeguard communal spaces.

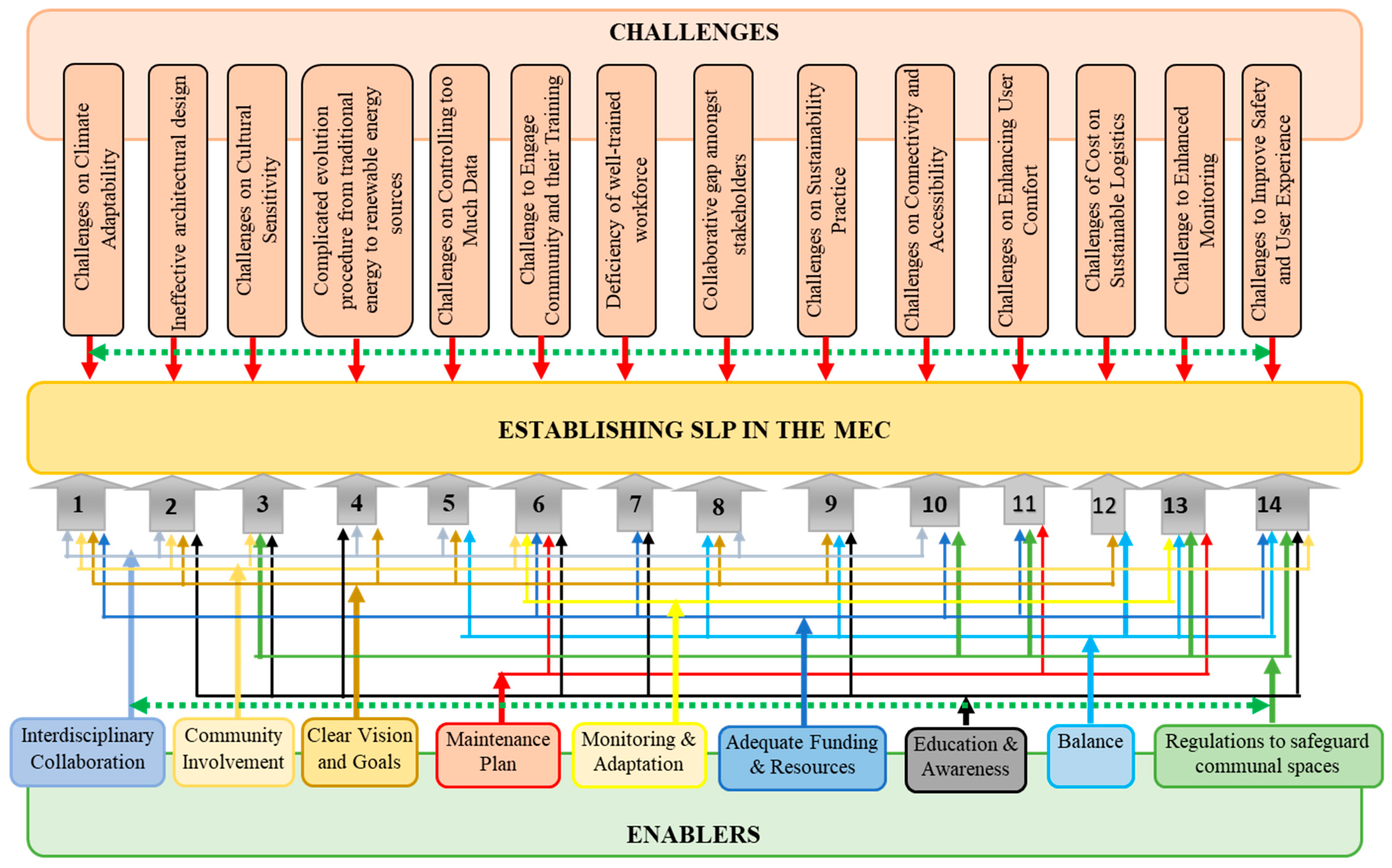

According to the experts, the challenges are diversified in nature, interrelated, and therefore, must be tackled with a group of enablers.

Figure 3 illustrates a framework that was developed from the challenges (

Figure 2) and enablers recommended by the experts.

Figure 3 graphically shows that the challenges are interrelated and can be solved by a group of enablers.

4.2. Analysis of the Questionnaire Survey Data and Validation of the Challenges

This section presents the analysis of the data collected through the community-based questionnaire survey, which validated the findings derived from the semi-structured interviews. The survey aimed to assess park users’ opinions on the challenges and priorities related to the development of sustainable and user-friendly logistics urban parks in the Middle Eastern context. A five-point Likert scale was employed, with 5 showing the highest level of importance/agreement and 1 representing the lowest level/disagreement, to collect participants’ evaluations across a range of design, operational, environmental, and user experience-related factors. This survey was distributed to over 1047 participants, 600 of whom responded.

Understanding the demographic profiles of respondents is essential for assessing the inclusivity and representativeness of SLUPs in MECs. The collected data presented in

Appendix B show a well-distributed sample across gender, age groups, and countries of residence. The gender composition of the survey participants (

Appendix B) revealed a well-balanced representation and presented both male and female perspectives, which were adequately reflected in the dataset and reduced gender bias in the findings. In terms of age distribution, the largest proportion of participants fell within the 18–29 age group, while the 60+ group accounted for the smallest share. This distribution shows a notable dominance of younger adults, who may have different priorities for SLUP design, accessibility, and amenities than older demographics. However, the presence of older age groups underscores the relevance of designing parks that accommodate multigenerational needs. Geographically, the respondents represented ten MECs, reflecting substantial regional diversity that ensured the incorporation of perspectives from all Gulf Cooperation Countries (GCCs) and other parts of the Middle East, enhancing the high validity of the findings.

Table 4 presents the importance of the key aspects of SLUPs within the MEC context. The analysis was based on the mean scores and Relative Importance Index (RII) values derived from the survey responses, with higher values showing greater perceived significance. Of the six key aspects evaluated, Maintenance and Lifecycle Management ranked first. This finding highlights the critical importance of ensuring the long-term functionality, safety, and usability of SLUPs. This reflects a strong regional emphasis on asset preservation and operational sustainability. Stakeholder Collaboration and Community Engagement ranked second. This underscores the inclusive planning processes and active community participation that are fundamental to the design of SLUPs.

Smart Technology Integration ranked third, suggesting that digital tools and smart infrastructure are increasingly valued for enhancing park efficiency, user experience, and sustainability. Green Transportation and Mobility followed in fourth place, showing the importance of sustainable access options such as cycling, walking, and public transport connectivity to reduce environmental impact. Waste Management Systems and Recycling was ranked fifth, suggesting moderate recognition of its role in SLUP operations, although it was still seen as less critical than lifecycle management and stakeholder engagement. Finally, Sustainable Infrastructure and Construction were assigned the lowest ranking, which may indicate that respondents view physical infrastructure improvements as less urgent than operational and management-oriented strategies in the MEC.

Table 5 presents the Evaluation Index System for assessing the SLUP performance within the MEC context, incorporating three main criteria: State of the Logistics Park, Operation of Settled Enterprises, and Social and Environmental Contributions (found in

Table 2). Facilities emerged as the most important factor across the entire index system, showing that well-developed and adequately maintained facilities are perceived as the backbone of effective SLUP operations. Service Level ranked second, emphasizing the importance of high-quality service provision in ensuring operational efficiency and satisfaction. Transportation accessibility and external environment ranked third and fourth, respectively, highlighting the value of efficient transport linkages and favourable environmental conditions. Impact Zone, Information Level, and Finance ranked lower, suggesting that while these aspects are relevant, they are considered less critical than core facilities and service quality.

For the Operation of Settled Enterprises criterion, enterprise activities ranked third overall and first within its category, reflecting the significance of active, diverse, and well-managed enterprise operations in enhancing the vitality. Enterprise Scale, however, received the lowest RII in the system, suggesting that the size of enterprises is less influential than the quality and scope of their activities. In the Social and Environmental Contributions criterion, Social Contribution ranked highest, underscoring the recognition of logistics parks as important social assets that foster community engagement and provide societal value. Environmental Contribution followed closely, indicating awareness of ecological considerations, whereas Economic Contribution ranked lower, suggesting that direct financial benefits are not perceived as the foremost priority compared to social and environmental outcomes.

Table 6 outlines the perceived level of agreement with the challenges of developing and managing SLUPs in MECs. The most critical challenge identified was the Stakeholder Collaboration Gap, highlighting a strong consensus that fragmented communication and a lack of coordination among relevant actors hinder effective park development and operations. This was closely followed by High Land Price, User-Friendliness, and Social Acceptance, emphasizing the financial constraints and importance of designing parks that align with community needs and cultural expectations. Complicated Energy Transition and Deficiency of Trained Workforce ranked fourth and fifth, respectively, indicating the dual challenges of transitioning to renewable or low-carbon energy systems and ensuring a skilled labor force to operate and maintain sustainable logistics infrastructure. Lack of government motivation and the harsh local climate also featured prominently, underscoring the combined influence of policy commitment and environmental constraints in shaping project viability.

Moderately ranked challenges were Expensive Sustainable Logistics and Poor Maintenance and Management, reflecting concerns over the operational and cost burdens of sustainable solutions. Ineffective Architectural Design and Socio-Cultural Barriers further pinpoint design inadequacies and social dynamics that may limit park use and functionality. Lower-ranked challenges, such as Limited Resources, Lack of Clear Guidelines, and Lack of Infrastructure, suggest that they are perceived as less pressing than strategic and socioeconomic factors. The least significant barriers were Lack of Awareness and Interest, Sociability Issues, and Accessibility Challenges in the MEC.

Cronbach’s alpha test is a widely used statistical measure that evaluates the internal reliability of a set of items within a survey instrument. It measures connection of a cluster of things and provides a sign of whether they measure the same underlying construct [

42]. In this study, the trustworthiness of the survey device produced a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.89, reflecting a high level of internal consistency among the assessed items.

Appendix C presents the correlation matrix analysis of the key aspects, evaluation index system, and challenges of SLUPs in the MEC context. This revealed a complex web of positive and negative relationships. Challenges related to environmental conditions, such as Harsh Local Climate, exhibit strong positive correlations with Smart Technology Integration (r = 0.98), showing that technology is critical in mitigating environmental constraints. Meanwhile, socio-cultural barriers and lack of awareness correlate positively with several evaluation criteria, emphasizing the need to address social factors in sustainable logistics development.

Strong positive correlations are observed between Finance and Waste Management Systems and Recycling (r = 0.82), as well as Information Level (r = 0.95), suggesting that the financial resources are closely linked to environmental management and information availability. Service Level shows an exceptionally strong positive correlation with Stakeholder Collaboration and Community Engagement (r = 0.98), emphasizing that active collaboration significantly enhances service quality. Challenges such as lack of infrastructure correlate highly with Waste Management Systems and Recycling (r = 0.97) and Finance (r = 0.85), indicating that inadequate infrastructure constrains financial investment and environmental efforts. Smart Technology Integration correlates moderately and positively with Impact Zone (r = 0.56) and Environmental Contribution (r = 0.56), highlighting the importance of technology for spatial and environmental improvements. In contrast, several notable negative correlations highlight potential conflicts or independent influences within the system. For instance, Smart Technology Integration negatively correlates with Stakeholder Collaboration & Community Engagement (r = −0.07), and Maintenance and Lifecycle Management also shows a negative correlation with Green Transportation and Mobility (r = −0.06). These negative associations suggest that certain technological or operational aspects might not align perfectly with social engagement or mobility efforts. User-Friendliness and social acceptance consistently show weak correlations with several operational and infrastructural challenges, including Maintenance and Lifecycle Management (r = −0.15) and Facilities (r = −0.14). This suggests that improving user experience may require addressing gaps in management and infrastructure.

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with oblimin rotation was conducted to identify the underlying dimensions influencing perceptions of SLUP. Before extracting factors, it is essential to verify data suitability using KMO > 0.6: Acceptable; >0.8 excellent and Bartlett Sig. < 0.05: indicates sufficient correlations for factor analysis.

As shown in

Table 7, the KMO value of 0.542 indicates moderate sampling adequacy, which is just above the minimum acceptable threshold of 0.5. This means that while the sample is sufficient to extract meaningful factors, caution should be applied when interpreting weaker loadings. Bartlett’s test is highly significant (

p < 0.001), confirming that the correlation matrix is not an identity matrix. This validates the use of factor analysis for this dataset, and we can proceed to extract meaningful components that represent the key aspects of SLUPs.

For the evaluation index system illustrated in

Table 8, a KMO of 0.706 indicates good sampling adequacy, so the correlations between variables suffice for factor extraction. Bartlett’s test is highly significant, confirming that the inter-item correlations are strong. This suggests that the Evaluation Index items measure related constructs and can be effectively grouped into coherent factors. Strong sampling adequacy increases confidence in the reliability of the extracted factors.

Regarding the challenges of SLUPs, as shown in

Table 9, the KMO value of 0.818 is excellent, showing that the sample size and inter-item correlations are highly suitable for factor analysis. Bartlett’s test is significant at

p < 0.001, confirming that the correlation matrix is not an identity, and thus the items are related enough to be factorable. This provides strong assurance that the subsequent factors extracted will reflect the meaningful underlying challenges in implementing SLUPs.

Communalities reflect the proportion of each variable’s variance explained by the extracted factors. Values above 0.50 are strong indicators that the factor structure adequately represents the variables.

As shown in

Table 10, all items of key aspects of SLUPs exceed the 0.50 threshold, except for some minor cross-loadings (e.g., Stakeholder Collaboration), which is theoretically justifiable because it impacts multiple aspects of SLUP implementation. High communalities for infrastructure and maintenance items suggest these are core pillars of SLUPs and strongly capture their underlying dimensions.

As shown in

Table 11, most items have extraction >0.50, reflecting strong factor representation, with the exception of Facilities (Question 1) = 0.067 → very low, indicating weak factor contribution, which was retained for theoretical relevance, as it conceptually belongs to the operational and spatial performance factor. Low communalities for some variables are common in social research and do not invalidate the factor solution if theoretically justified. Keeping these items ensures the model aligns with practical aspects of urban logistics evaluation.

As shown in

Table 12, most items >0.50, except for Lack of Resources (Q5), Cost Constraints (Q6), and Data Gaps (Q11) <0.50, were retained because of conceptual importance, as these are critical barriers in SLUP implementation despite weaker statistical representation.

The lower communalities for certain challenges suggest that they do not align strongly with the extracted factors but remain significant. This highlights areas where SLUP implementation faces unique obstacles that may not strongly correlate with other challenges.

As shown in

Table 13, factors with eigenvalues >1 were retained; the Scree Plot in

Figure 4 visually confirms factor numbers, and retaining four factors in all sections ensures a balance between parsimony and explanatory power. The variance explained was between 70 and 80%, indicating that these factors successfully captured most of the information in the dataset. The scree plot confirmed the four-factor solution, with a clear “elbow” after the fourth component, supporting the decision to keep these factors.

As shown in

Table 14, each factor was conceptually coherent. Eco-Friendly Operations combines environmental actions (waste, mobility), Technology Integration stands alone reflecting the digital transformation dimension, Maintenance and Lifecycle form a distinct operational factor, and infrastructure emerges as a structural pillar. The cross-loadings were minimal and theoretically justifiable.

As shown in

Table 15, financial/economic items load strongly on Factor 1, forming a coherent dimension of resource impact. Operational/service performance is captured in Factor 2. Factor 3 combines social and environmental responsibilities, highlighting a social–external nexus. Factor 4 represents the spatial and environmental impact, which is essential for urban planning.

As illustrated in

Table 16, Factor 1 captures governance and environmental issues. Factor 2 reflects technical and operational barriers. Factor 3 represents resource and cost limitations, and Factor 4 isolates infrastructure constraints. This breakdown allows researchers to target interventions specifically for each type of challenge faced.

The component transformation matrix shows the correlations between factors before and after rotation and verifies whether the extracted factors are orthogonal (independent) or correlated. This is important because

Low correlations indicate independence, validating the use of factor scores in clustering and regression analyzes.

High correlations would suggest an overlap between factors, requiring oblique rotation instead.

As shown in

Table 17, all off-diagonal values are close to zero, confirming that the four factors are almost completely independent. Factor 1 (Eco-Friendly Operations) is weakly correlated with Factor 2 (Smart Technology Integration), which is conceptually reasonable since technology can support but is not identical to environmental operations. This orthogonality justifies using factor scores for cluster analysis without worrying about multicollinearity.

As shown in

Table 18, the factors show very low correlations, confirming the independence of constructs. Factor 1 (Financial/Economic Contributions) is slightly correlated with Factor 2 (Operational Performance), which makes sense since financial resources often support operations. Factor 3 (Social/External Environment) and Factor 4 (Spatial/Environmental Impact) are nearly orthogonal, reflecting distinct conceptual dimensions.

As shown in

Table 19, the factor correlations were extremely low, confirming that the four-factor solution separated distinct challenge types. Factor 1 (Institutional/Environmental) is slightly correlated with Factor 2 (Technical/Operational), which is reasonable because technical issues are often affected by institutional or regulatory constraints. This matrix confirms suitability for independent factor scores in clustering analysis, ensuring each challenge dimension contributes unique information.

As shown in

Table 20, the factor scores condense multiple related survey items into a single numeric value for each respondent, representing their position on each latent factor. These scores are crucial for cluster analysis to group participants based on the SLUP dimensions. Each factor score was standardized and could be compared across respondents. These scores allow for grouping respondents who emphasize similar SLUP priorities (e.g., environmental and technical challenges). Factor scores are unbiased representations of latent constructs that support objective cluster classification.

Cluster analysis was conducted to categorize respondents into homogeneous groups based on their responses to SLUPs (key aspects, the evaluation index, and challenges). It identifies differing priorities among participants and provides practical insights for SLUP implementation.

As shown in

Table 21, the age distribution across clusters reveals notable differences that can inform targeted SLUP strategies. Cluster 1 comprises of younger participants aged 18–29 (making up 38% of the group). This shows the youth-oriented priorities and engagement strategies that would be most effective for this cluster. Cluster 2 includes a wider age range, spanning younger to middle-aged respondents (18–44), suggesting the need for flexible approaches that accommodate diverse preferences and capacities. Cluster 3 shows a balanced distribution across all age categories, implying that its design and policy recommendations should be broadly inclusive rather than age-specific. In contrast, Cluster 4 contains a larger proportion of older participants (60+), highlighting the importance of designing interventions and support mechanisms tailored to the needs, limitations, and preferences of older users. These age-based distinctions reinforce the value of differentiated strategies that align with each cluster’s demographic profile.

As illustrated in

Table 22, the gender distribution across the clusters reveals meaningful differences that can guide more targeted SLUP strategies. Clusters 1 and 2 show a slightly male-dominant composition, suggesting that communication and engagement strategies for these groups may benefit from approaches that account for male participation patterns and preferences. In contrast, Clusters 3 and 4 display a more balanced gender distribution, indicating the need for gender-neutral or inclusively designed strategies that address the needs and expectations of both male and female respondents.

As shown in

Table 23, the geographic distribution across clusters indicates clear regional patterns that can inform context-sensitive SLUP strategies. Cluster 1 shows a strong presence of respondents from Saudi Arabia and the UAE, suggesting that Gulf-focused initiatives aligned with local planning practices and environmental priorities would be relevant. Cluster 2 presents a more diverse regional composition, with notable representation from Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, indicating the need for adaptable strategies that accommodate varying national contexts within the Gulf region. Cluster 3 includes a higher proportion of participants from Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq, pointing to the importance of Levant-oriented approaches that consider differing socio-environmental challenges and institutional frameworks. Cluster 4 demonstrates a balanced mix of countries, with greater representation from Qatar and Oman, highlighting the need for broadly inclusive yet regionally attuned communication and design strategies.

As shown in

Table 24, Cluster 1 (86 participants) places moderate emphasis on environmental initiatives and green operations (FAC4) but shows a low engagement with technical and financial aspects (FAC1-FAC3). These respondents may benefit from targeted training or support in operational and technical areas. Cluster 2 (229 participants) participants exhibit a balanced focus across all factors, showing readiness to engage with projects that combine technical operations, administrative tasks, and environmental concerns. Cluster 3 (127 participants) respondents emphasize technical and administrative aspects (FAC2) while showing limited interest in environmental initiatives and financial contributions. Strategies should target their environmental engagement. Cluster 4 (158 participants) respondents show low focus across all factors, with particularly negative scores in FAC4, suggesting the need for comprehensive support in green initiatives and awareness campaigns.

As shown in

Table 25, Cluster 1 (66 participants) participants are highly engaged in operational and technical processes (FAC1 and FAC3), yet their institutional or organizational involvement is weak. They may need support in governance and procedural alignment. Cluster 2 (120 participants) focuses primarily on environmental initiatives and operational activities; technical challenges are not its main concern. This group can effectively contribute to sustainability-focused tasks. Cluster 3 (134 participants) places strong emphasis on institutional and administrative aspects, with a limited engagement in environmental and technical areas. Interventions could enhance their performance in green initiatives. Cluster 4 (280 participants), the largest group, demonstrates a balanced engagement across all factors, indicating readiness for diverse SLUP projects and operations.

As depicted in

Table 26, Cluster 1 (158 participants) respondents face high technical challenges (FAC3) but maintain moderate engagement with operational and administrative aspects. Targeted technical support may improve their performance. Cluster 2 (164 participants) is primarily concerned with operational and institutional factors, while technical challenges are less critical. They can lead to administrative improvements effectively. Cluster 3 (130 participants) focuses on institutional/administrative aspects (FAC2), with low attention to technical and environmental challenges, suggesting the need for balanced interventions. Cluster 4 (148 participants) participants show low engagement across all challenge factors, especially institutional ones, showing the highest need for comprehensive support and capacity building.

The ANOVA results shown in

Table 27 indicate that the

p-values (Sig.) for all three dimensions are greater than 0.05, showing no statistically significant differences between age groups in their assessment of key aspects of SLUPs, performance evaluation, or perceived challenges. This implies that respondents across different age groups have similar perceptions regarding the critical components of sustainable land-use planning. These results also suggest a consistent understanding of SLUP across generations, reflecting shared awareness and perspectives among respondents.

As shown in

Table 28, the analysis of mean scores indicates a high level of agreement across age groups regarding sustainable land-use planning in SLUP. For the key aspects of SLUPs, mean scores range from 4.1667 to 4.1905, demonstrating strong consensus on their importance. Similarly, the evaluation index system and performance scores are consistent, ranging from 4.0455 to 4.0853, suggesting comparable evaluations of performance among all age groups. Challenges associated with SLUPs also show equivalent results, with mean scores ranging from 3.7598 to 3.8200, indicating no significant differences in how challenges are considered. Overall, the Tukey HSD results support the ANOVA findings, reinforcing the consistency of perceptions across different age groups.

The ANOVA and Tukey HSD results demonstrate that age does not influence respondents’ evaluations of the three SLUP dimensions: key aspects, performance evaluation, or challenges. All age groups share a uniform perception of sustainable land-use planning, indicating balanced understanding and stable awareness across generations. These findings suggest that policies or training programs related to SLUP can target all age groups using the same approach without requiring age-specific adjustments, facilitating efficient planning and implementation.

As shown in

Table 29, the independent samples

t-test results indicate that mean scores for all three SLUP dimensions are very similar between males and females, reflecting comparable perceptions regarding key aspects, performance, and challenges. Furthermore, standard deviations are closely aligned, which indicates consistent response variability within each gender group.

Levene’s test indicates no significant differences in variance between genders (all

p > 0.05), allowing the assumption of equal variances (

Table 30). The independent samples T-test results show that all

p-values (Sig. 2-tailed) exceed 0.05, indicating no statistically significant differences across genders in their assessment of key aspects of SLUPs, performance evaluation, or challenges.