Achieving Human-Centered Smart City Development in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Smart City Development: From Techno-Centrism to Human-Centrism

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

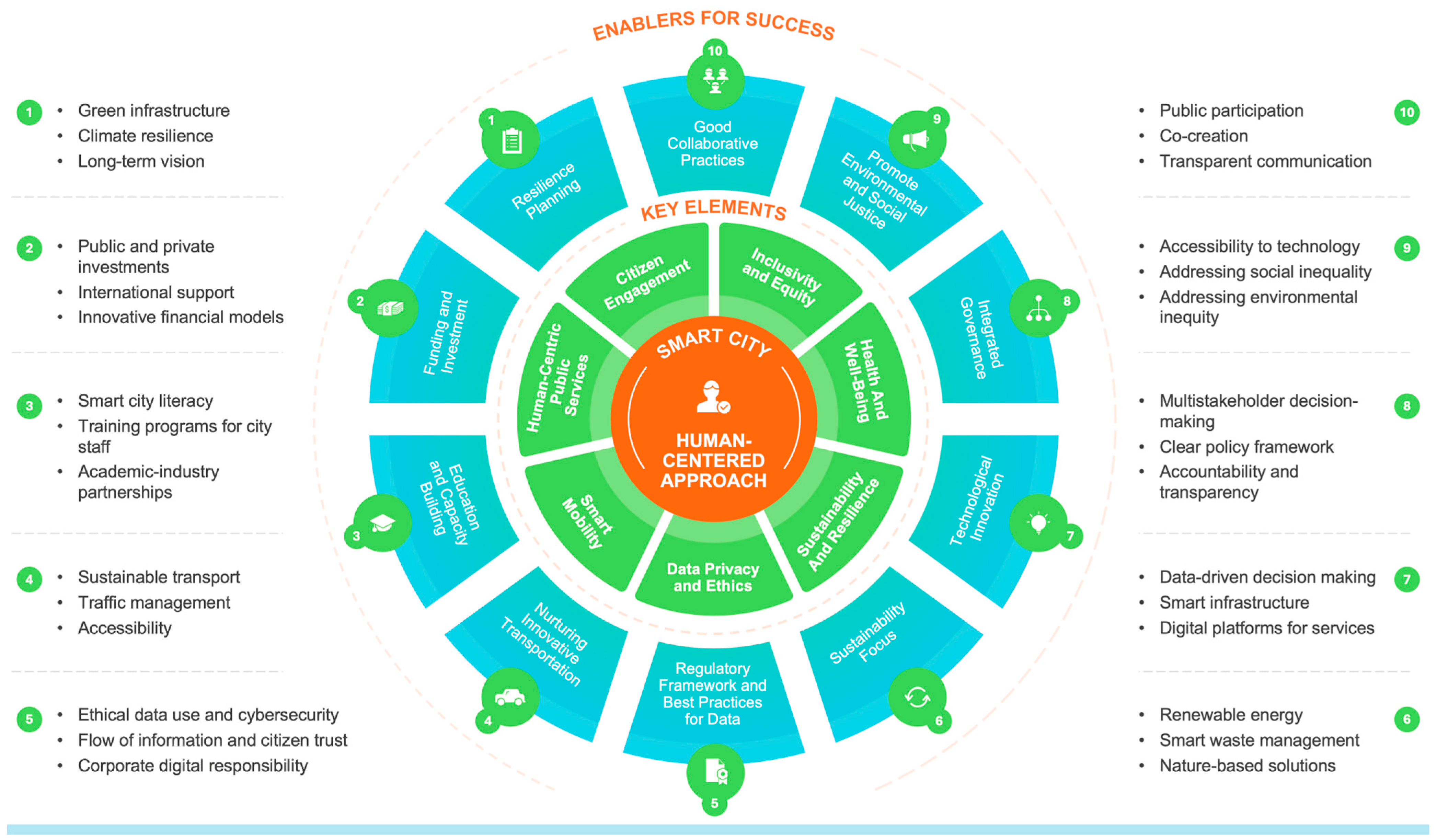

4.1. Human-Centered Smart City Framework

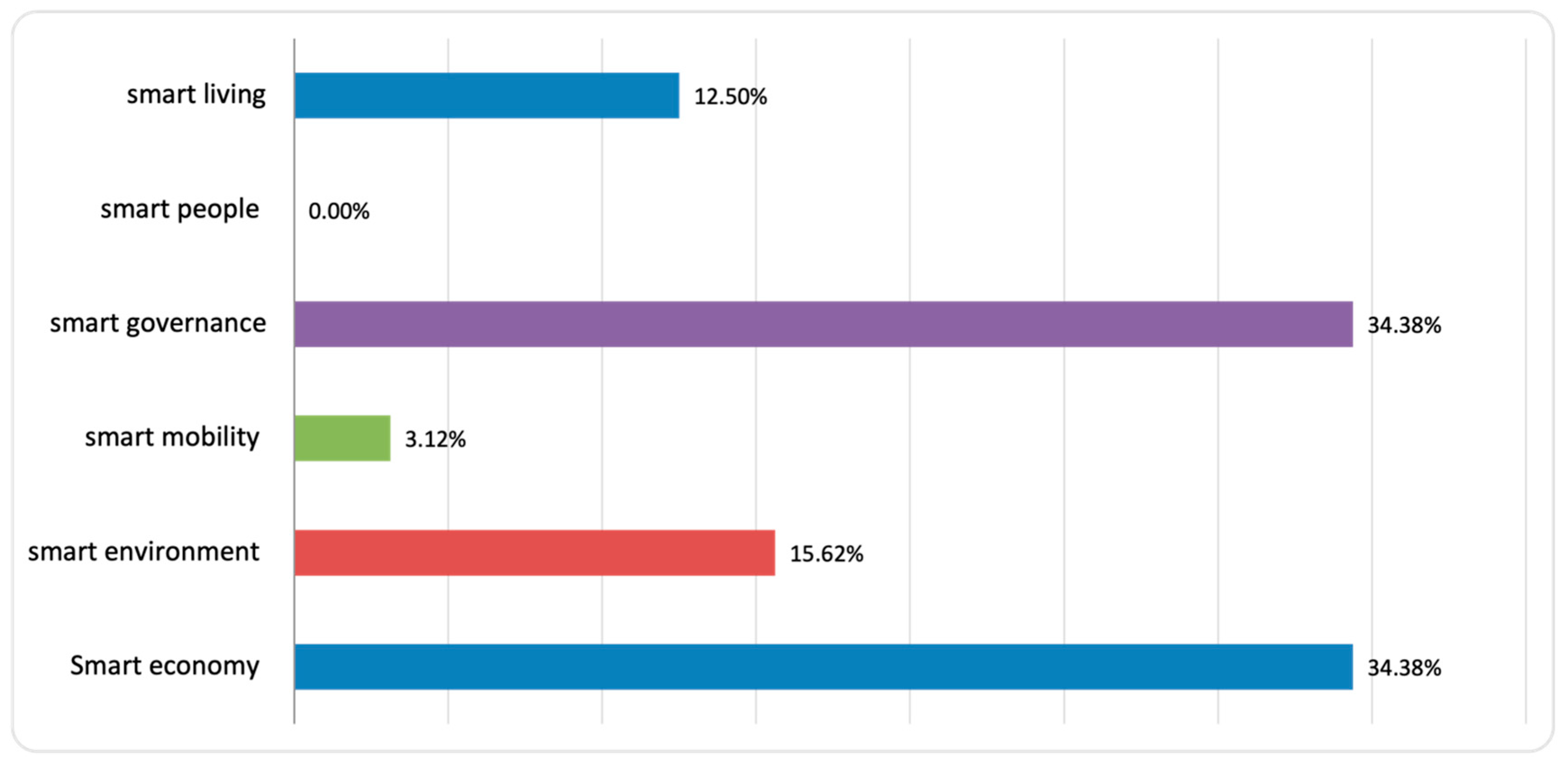

4.2. Review of Human-Centered Smart City Development in Saudi—Status and Challenges

4.3. Expert Opinions on Human-Centered Smart City Development

4.4. Human-Centered Smart City Cases

4.5. Lessons and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank Group. Urban Development. 2023. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview#:~:text=Today%2C%20some%2056%25%20of%20the,billion%20inhabitants%20%E2%80%93%20live%20in%20cities (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- UN-Habitat. World Smart Cities Outlook 2024; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Landa, I.; Gonzalez Ochoantesana, I.; Anaya Rodríguez, M. The Importance of a Human-Centered Approach in Public participation to Develop Citizen-Oriented Smart Neighborhoods. 2023. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11984/6311 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Bleja, J.; Neumann, S.; Krueger, T.; Grossmann, U. A Human-Centered Design Approach for the Development of a Digital Care Platform in a Smart City Environment: Implications for Business Models. In Companion Proceedings of the Web Conference 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.; Maabreh, M.; Ghaly, M.; Khan, K.; Qadir, J.; Al-Fuqaha, A. Developing future human-centered smart cities: Critical analysis of smart city security, Data management, and Ethical challenges. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2022, 43, 100452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Ruan, M.; Vadivel, T.; Daniel, J.A. Human-centered applications in sustainable smart city development: A qualitative survey. J. Interconnect. Netw. 2022, 22 (Suppl. S4), 2146001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Desouza, K.C.; Butler, L.; Roozkhosh, F. Contributions and risks of artificial intelligence (AI) in building smarter cities: Insights from a systematic review of the literature. Energies 2020, 13, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, N.; Lee, K.J. Exploratory research on the success factors and challenges of Smart City projects. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2014, 24, 141–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMD. Smart City Index 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.imd.org/smart-city-observatory/home/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Fabrègue, B.F.; Bogoni, A. Privacy and security concerns in the smart city. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 586–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, B.P.; Bangwal, D. People centric governance model for smart cities development: A systematic review, thematic analysis, and findings. Res. Glob. 2024, 9, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.I.; Cobbinah, P.B. Can rapid urbanization be sustainable? The case of Saudi Arabian cities. Habitat Int. 2023, 139, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaul, V.; Sumant, O. Saudi Arabia Smart Cities Market Size, Share, Competitive Landscape and Trend Analysis Report, by Functional Area: Saudi Arabia Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast, 2020–2027. 2021. Available online: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/saudi-arabia-smart-cities-market-A10247 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Tolentino, J. Saudi’s Top Firms to Set Up Digital Infrastructure Hub in KAEC. 2023. Available online: https://www.constructionweekonline.com/projects-tenders/saudis-top-firms-to-set-up-digital-infrastructure-hub-in-kaec (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Moumen, N.; Radoine, H.; Nahiduzzaman, K.M.; Jarar Oulidi, H. Contextualizing the Smart City in Africa: Balancing Human-Centered and Techno-Centric Perspectives for Smart Urban Performance. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 712–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Chen, J.H.; Wei, H.H.; Su, Y.C. Towards people-centric smart city development: Investigating the citizens’ preferences and perceptions about smart-city services in Taiwan. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, M.; Aina, Y.A.; Yigitcanlar, T. Smart and Sustainable Doha? From Urban Brand Identity to Factual Veracity. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashkevych, O.; Portnov, B.A. Human-centric, sustainability-driven approach to ranking smart cities worldwide. Technol. Soc. 2023, 74, 102296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Yan, B.; Huang, Y.; Sarker, M.N.I. Big data-driven urban management: Potential for urban sustainability. Land 2022, 11, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A. Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity Centered; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262548304/design-for-a-better-world/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Luo, J.; Liu, P.; Xu, W.; Zhao, T.; Biljecki, F. A perception-powered urban digital twin to support human-centered urban planning and sustainable city development. Cities 2025, 156, 105473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvi, L.T.; Behzadfar, M.; Shemirani, S.M. Defining the social-sustainable framework for smart cities. Int. J. Hum. Cap. Urban Manag. 2023, 8, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarelli, G.; Chiesi, L.; Chirici, G.; Galmarini, B.; Mancuso, S.; Moi, J.; De Domenico, M. Lessons from complex networks to smart cities. Nat. Cities 2025, 2, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.I.; Yigitcanlar, T. Understanding Smart Governance of Sustainable Cities: A Review and Multidimensional Framework. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florentin, K.M.; Onuki, M.; Yarime, M. Facilitating citizen participation in greenfield smart city development: The case of a human-centered approach in Kashiwanoha international campus town. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2024, 15, 100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Zealand Treasury. The Wellbeing Budget. 2019. Available online: https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2019-06/b19-wellbeing-budget.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- European Commission. Berlin Declaration on Digital Society and Value-Based Digital Government. 2020. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/berlin-declaration-digital-society-and-value-based-digital-government (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- McBride, K.; Hammerschmid, G.; Cingolani, L. Policy Brief: Human Centric Smart Cities—Redefining the smart city. Hertie School—Centre for Digital Governance: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mills, D.E.; Izadgoshasb, I.; Pudney, S.G. Smart city collaboration: A review and an agenda for establishing sustainable collaboration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, C.C.; Håkonsson, D.D.; Obel, B. A smart city is a collaborative community: Lessons from smart Aarhus. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 59, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, A.P.; Da Costa, E.M.; Furlani, T.Z.; Yigitcanlar, T. Smartness that matters: Towards a comprehensive and human-centred characterisation of smart cities. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2016, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.; Petter, S.; Grover, V.; Thatcher, J.B. Information technology identity: A key determinant of IT feature and exploratory usage. MIS Q. 2020, 44, 983–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, H.; Soe, R.M.; Toiskallio, K.; Mora, L. How do academic smart city centres operate in complex environments? A business model perspective. Cities 2024, 152, 105211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismagilova, E.; Hughes, L.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Security, privacy and risks within smart cities: Literature review and development of a smart city interaction framework. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 24, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyngäs, H. Qualitative research and content analysis. In The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, P.; Youssef, A.; Hajkova, V. Recent developments in smart city assessment: A bibliometric and content analysis-based literature review. Cities 2022, 126, 103709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neom. Changing the Future of Design Construction. 2024. Available online: https://www.neom.com/en-us/our-business/sectors/design-and-construction (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Asmyatullin, R.R.; Tyrkba, K.V.; Ruzina, E.I. Smart cities in GCC: Comparative study of economic dimension. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 459, p. 062045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- le Duc, C. The invested city. In The Climate City; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: London, UK, 2022; pp. 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Turki, M.; Jamal, A.; Al-Ahmadi, H.M.; Al-Sughaiyer, M.A.; Zahid, M. On the potential impacts of smart traffic control for delay, fuel energy consumption, and emissions: An NSGA-II-based optimization case study from Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almesalm, S.; Alfowzan, M.; Alajouri, H. A Healthy Smartphone Application to Enhance Patient Services in Saudi Arabia in a Human Centered Design Approach. In Advances in Usability and User Experience, Proceedings of the AHFE 2019 International Conferences on Usability & User Experience, and Human Factors and Assistive Technology, Washington, DC, USA, 24–28 July 2019; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.; Khan, M.A.; Gharaibeh, N.K.; Gharaibeh, M.K. Big data for smart cities: A case study of NEOM city, Saudi Arabia. In Smart Cities: A Data Analytics Perspective; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi, A.K.; Abidoye, R.B.; Lam, T.Y. Critical review of citizens’ participation in achieving smart sustainable cities: The case of Saudi Arabia. In Science and Technologies for Smart Cities; International Summit Smart City 360°; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutambik, I.; Almuqrin, A.; Alharbi, F.; Abusharhah, M. How to encourage public engagement in smart city development—Learning from Saudi Arabia. Land 2023, 12, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulf Construction. Make Riyadh Human-Centric, Sustainable and Innovative City, Says JLL. 2023. Available online: https://gulfconstructiononline.com/ArticleTA/414729/Make-Riyadh-human-centric,-sustainable-and-innovative-city,-says-JLL (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Zamin, N.; Mary, M.E.; Muzaffar, A.W.; Ku-Mahamud, K.R.; Residi, M.A.I. Evaluation of Smart Community Engagement in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. In International Visual Informatics Conference; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madakam, S.; Bhawsar, P. NEOM smart city: The city of future (the urban Oasis in Saudi desert). In Handbook of Smart Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.J. Madinah: A Jewel Committeed to the Challenges of the Future. 2024. Available online: https://www.mda.gov.sa/News/Details/3105 (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Alotaibi, A.; Alsubaie, D.; Alaskar, H.; Alhumaid, L.; Thuwayni, R.B.; Alkhalifah, R.; Alhumoud, S. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Era of Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Computing and Information Technology (ICCIT), Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, 25–27 January 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciej Błaszak, M.B.; Artur Fojud, A.F. Three dimensions of a useful city. Man Soc. 2016, 42, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Ali, A. Sustainable green energy transition in Saudi Arabia: Characterizing policy framework, interrelations and future research directions. Next Energy 2024, 5, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, A.A.; Doheim, R.M. Humanizing Al-Madinah Al-Munawarah Streets: From a Car-Centric City to a Healthy, Culturally Vibrant, and Climate-Resilient City. In Designing Healthy Cities: Integrating Climate-Resilient Urbanism for Sustainable Living; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Deeb, Y.I.; Alqahtani, F.K.; Bin Mahmoud, A.A. Developing a Comprehensive Smart City Rating System: Case of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 04024012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondiviela, J.A. SmartCities. Technology as enabler. In Beyond Smart Cities: Creating the Most Attractive Cities for Talented Citizens; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 103–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahimi, T.; Bensaid, B. Smart Villages and the GCC Countries: Policies, Strategies, and Implications. In Smart Villages in the EU and Beyond; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2019; pp. 155–171. [Google Scholar]

- Keh, E.; Lawrence, M.; Sauz, R.; Dadashi, N.; Homayounfar, N. The Ethical Smart City Framework Toolkit: An Inclusive Application of Human-Centered Design and Public Engagement in Smart City Development. IxD&A 2021, 50, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastjuk, I.; Trang, S.; Papageorgiou, E.I. Smart cities and smart governance models for future cities: Current research and future directions. Electron. Mark. 2022, 32, 1917–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skubis, I.; Wolniak, R.; Grebski, W.W. AI and Human-Centric Approach in Smart Cities Management: Case Studies from Silesian and Lesser Poland Voivodships. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šurdonja, S.; Giuffrè, T.; Deluka-Tibljaš, A. Smart mobility solutions–necessary precondition for a well-functioning smart city. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 45, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A.; Alani, N.H. Human-Centric Collaboration and Industry 5.0 Framework in Smart Cities and Communities: Fostering Sustainable Development Goals 3, 4, 9, and 11 in Society 5.0. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 1723–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudowsky, N.; Sotoudeh, M.; Capari, L.; Wilfing, H. Transdisciplinary forward-looking agenda setting for age-friendly, human centered cities. Futures 2017, 90, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, Y.A. Achieving smart sustainable cities with GeoICT support: The Saudi evolving smart cities. Cities 2017, 71, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. E-Participation Index 2022. 2023. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/About/Overview/E-Participation-Index (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- International Communication Union. Global Cybersecurity Index 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Cybersecurity/Pages/global-cybersecurity-index.aspx (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- World International Property Organization. The Global Innovation Index 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/global_innovation_index/en/2022/ (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- UN-Habitat Speech at the Smart Madinah Forum, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2023. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2023/02/02_2023_speech_madinah_smart_forum.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Al-Ghabra, N. Toward Sustainable Smart Cities: Concepts Challenges. Archit. Plan. J. 2022, 28, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, Z.; Goodman, N.; Wolfe, D.A. How ‘smart’ are smart cities? Resident attitudes towards smart city design. Cities 2023, 141, 104442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.I.; Abubakar, I.R. Developing a sustainable water conservation strategy for Saudi Arabian cities. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 23, 101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfaqih, M.; Alharbi, S.A. Associated information and communication technologies challenges of smart city development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maliki, S.Q.A.K.; Ahmed, A.A.; Nasr, O.A. The Establishment of Smart Cities: Existing Challenges and Opportunities–The Case of Saudi Arabia. In Smart Cities—Foundations and Perspectives; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshuwaikhat, H.M.; Aina, Y.A.; Binsaedan, L. Analysis of the implementation of urban computing in smart cities: A framework for the transformation of Saudi cities. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wang, S.; Zhai, W. Human-centric vs. technology-centric approaches in a top-down smart city development regime: Evidence from 341 Chinese cities. Cities 2023, 137, 104271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, Y.A.; Wafer, A.; Ahmed, F.; Alshuwaikhat, H.M. Top-down sustainable urban development? Urban governance transformation in Saudi Arabia. Cities 2019, 90, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi, A.K.; Abidoye, R.B.; Lam, T.Y. The impact of stakeholders’ management measures on citizens’ participation level in implementing smart sustainable cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldegheishem, A. Assessing the progress of smart cities in Saudi Arabia. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doheim, R.M.; Farag, A.A.; Badawi, S. Smart city vision and practices across the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A review. In Smart Cities: Issues and Challenges; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutambik, I. Culturally Informed Technology: Assessing Its Importance in the Transition to Smart Sustainable Cities. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsheddi, A. The Impact of Socio-Cultural and Religious Values on the Adoption of Technological Innovation: A Case Study of Saudi Arabia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Canberra, Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Angelidou, M. Smart city policies: A spatial approach. Cities 2014, 41, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardito, L.; Ferraris, A.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Bresciani, S.; Del Giudice, M. The role of universities in the knowledge management of smart city projects. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 142, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IASP. Dhahran Techno Valley Company. 2024. Available online: https://www.iasp.ws/our-members/directory/@6015/dhahran-techno-valley-company (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Nuseir, M.T.; Basheer, M.F.; Aljumah, A. Antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions in smart city of Neom Saudi Arabia: Does the entrepreneurial education on artificial intelligence matter? Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1825041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, K.S.; Bryson, J.M. Public participation. In Handbook on Theories of Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Mittal, S.K.; Sharma, S. Role of e-trainings in building smart cities. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 111, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrón, V.M.; Gachet, D.; Penelas, J.L.E.; Pérez, O.G.; Martín de Pablos, F.; Muñoz Gil, R. Social inclusion in smart cities. In Handbook of Smart Cities; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 469–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaida, M. Madinah Smart City System: Managing and Monitoring Traffic, Emergency Services, and Crowds in The Haram. In Proceedings of the 2023 10th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 15–17 March 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 576–582. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10112506 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

| Sectors | Number |

|---|---|

| Public Sector (Directors/General Managers/Planners/Engineers) | 23 |

| Private Sector (Directors/Managers/Investor/Finance) | 6 |

| Academic Sector | 3 |

| Total | 32 |

| Component of Human-Centered Smart City (Case Studies) | Example Project/Cities | References |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge economy | Neom city features a retooled economic model built in the interest of technological advancement, citizen welfare, and a progressive society. | [37,38,39] |

| Technological hub | Dhahran techno valley, Khobar and Dhahran smart city, and Neom City all serve as digital hubs for further innovation in smart city development. | [40,41,42] |

| Knowledgeable citizens | Saudi Vision 2030 serves as a guide towards achieving knowledgeable citizens in a smart city approach in Saudi Arabia. | [43] |

| Active engagement | Jeddah smart city and Riyadh smart city concentrated on strengthening their smarts through boosting citizen involvement over digital channels. | [44,45] |

| Public participation | Riyadh city paving the way toward achieving public participation and community engagement. | [46,47] |

| Quality of life | Madinah smart city and Riyadh smart city both focused on improving the quality of life for citizens through inclusion, technology, and diversity. | [48,49,50] |

| Saudi Green Initiatives | Riyadh Smart City serves as a key player in green innovation in real estate, green financing in responsible investments, and green building projects. Madinah Humanizing Cities Initiative, which include the enhancement of green spaces. | [51,52] |

| Strong governance | Madinah smart city and Riyadh smart city both conveyed their vision towards featuring clear governance procedures that guarantee digital innovations and technologies meant for enhancing the well-being of citizens. | [5,48,53] |

| Social and humanistic inclusion | Neom City focuses on social and humanistic inclusion by advocating connections with the community, boosting interpersonal relationships, and allowing residents the opportunity to utilize services that boost general wellness. | [54] |

| Social capital | GCC smart cities prove social capital as an integral component of smart cities as it renders cities more resilient, promotes innovation, preserves diversity, and progressively improves the standard of living for inhabitants. | [55] |

| Item | Mean | Standard Deviation | Rank | Degree |

| Saudi smart city developers consider the socio-cultural aspect of urban development | 3.47 | 1.03 | 3 | Agree |

| Saudi smart city development promotes healthy and livable city principles | 4.04 | 0.95 | 2 | Agree |

| Centralized planning is a challenge to smart city development in Saudi | 4.28 | 0.57 | 1 | Strongly Agree |

| The knowledge centers such as universities provide adequate support and capacity for smart city development | 3.24 | 1.07 | 4 | Undecided |

| The Saudi smart city development ensures citizen participation | 3.12 | 1.05 | 5 | Undecided |

| Average | 3.63 | 0.934 | Agree | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almulhim, A.I.; Aina, Y.A. Achieving Human-Centered Smart City Development in Saudi Arabia. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100393

Almulhim AI, Aina YA. Achieving Human-Centered Smart City Development in Saudi Arabia. Urban Science. 2025; 9(10):393. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100393

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmulhim, Abdulaziz I., and Yusuf A. Aina. 2025. "Achieving Human-Centered Smart City Development in Saudi Arabia" Urban Science 9, no. 10: 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100393

APA StyleAlmulhim, A. I., & Aina, Y. A. (2025). Achieving Human-Centered Smart City Development in Saudi Arabia. Urban Science, 9(10), 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100393