1. Introduction: The Mise-en-scène

This article opens with an insight into different urban planning cultures from a historical perspective with regard to urban renewal programs, with the focus on one country’s contemporary experience in urban renewal in terms of policy design, implementation of projects, and their implications. This urban planning culture is examined in the context of Israel, with an emphasis on urban regeneration schemes since the year 2000, considering a variety of societal and ethical concerns. In the second part of this article, a selection of critical studies on this topic from the last five years is revisited, with special attention given to the existence of social sustainability elements in the different stages of regeneration, from conception to the projects’ outcomes. The selection of recently published critical studies is especially informative and useful for analysis, because it covers the years in which urban renewal policy gained momentum in practice, namely between 2018 and 2023. Through the examination of the recent literature, together with an analysis of several recent key governmental reports on this topic, we have shown that the discourse on urban social sustainability in Israel is currently disconnected from its urban renewal policy. Although the latter policy is not devoid of societal considerations, its targets and criteria of success are primarily conceptualized and measured by quantitative data. The last part of this article concludes that the combination of Israel’s contemporary urban renewal policy with urban social sustainability theory and policy design is an objective to be sought. This is against the background of the particularly high population density in Israel’s cities, expected to be one of the highest in the world by 2050, (Israel was created on independence following the end of the British Mandate in Palestine in 1948. The total area under Israeli law (including East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights) is approximately 22,000 square kilometers, and the total area under Israeli control (including the West Bank) is approximately 28,000 square kilometers. The country’s population size is 9,752,480 (2023 estimate), and its ethnic groups breakdown is: 73.6 percent Jews, 21.1 percent Arabs, and 5.3 percent others (without the West Bank, 2022 estimate). Approximately 93% of Israel’s population lives in urban areas. The country has 16 larger cities in which the population is over 100,000; and 77 localities in all that were granted official municipality (city) status (including four which are in the West Bank)), and to conform to current trends in the Global North, where social sustainability discourse is merging into urban regeneration discourse. The insight into a country-related planning culture provided by this article directly contributes to our continually consolidating understanding of urban renewal initiatives globally and their socio-ethical sensitivities—an understanding that is based on a collection of country-related experiences.

Since their first official implementation in the second half of the 19th century as a consequence of the Industrial Revolution, via post-World War II reconstruction, and up to contemporary densification as a policy goal, urban renewal in the Global North has been an umbrella term for a multiplicity of programs. Historically as much as at present, the motives behind such programs have always been case sensitive (site related in conformity with a certain state or the local authority’s planning culture), reflecting changing governmental and public policy emphases. Differences between these cultures can be discerned by their planning culture. For instance, differences were apparent between England and France by the turn of the 19th century, with the British government pursuing softer urban regeneration policies based on a progressive agenda of social reform, in comparison to Paris’ highly centralized and physically destructive regeneration programs led by Baron Haussmann and Napoleon III, based on aesthetics and utility rationales [

1,

2]. Another classic comparison in this regard between both countries is their approach to and implementation of ‘Garden City’ redevelopment schemes in suburban contexts in the interwar period, that is, in the form of extensive low-cost housing policies in France versus targeting higher-income residents through middle-class housing estates in England [

3,

4]. Further, during the period of the Industrial Revolution and the accompanying climate of imperialism, each colonial power’s metropolitan planning approach often extended to its respective overseas possessions.

Differences between planning cultures can also be discerned at the long-term national level, as in the case of the US experience of urban renewal. In response to inner-city deterioration following the migration of higher-income classes to the suburbs in the 1940s and 1950s, top-down planning policies were focused on the demolition of urban textures of low socio-economic sectors [

5]. These controversial programs were criticized as a mechanism for social control by further marginalizing black and immigrant populations. This paved the way for the ‘Model Cities’ approach of the 1960s and 1970s, which sought to empower marginalized residents through public-participation processes [

6,

7]. By the 1990s, neo-liberal approaches towards urban regeneration in the US opened the market to public–private partnerships (PPP) and mixed-income housing [

8], which was gradually becoming a global tendency. Among the main issues resulting from the bias of private interests are gentrification and densification of inner-city residential quarters, often without providing appropriate infrastructure; the creation of gated communities in the erstwhile public space; the removal of the original residents from these quarters/projects; and the demolition of historic heritage [

9,

10,

11].

The Israeli experience in politics and policies of planned interventions in distressed urban neighborhoods corresponds perfectly with these three generations’ experience in the US and was directly influenced by it. As shown by Naomi Carmon [

12,

13], during the couple of decades following its independence, Israel completed extensive urban housing projects of tenement buildings for the many Jewish refugees who came from Europe and the Muslim world (

Figure 1). The extensive building of these housing projects during the 1950s and 1960s—known as

shikuney rakevet, i.e., ‘train blocks’, because of the prolonged form of each unit created by the arrangement of a few entrances in a row—coincided with ‘slum clearance’ operations. The latter involved the eradication of multiple sites of impoverished provisional housing such as tent cities with only basic infrastructure, which had formerly provided housing for tens of thousands of immigrants.

Then, inspired by the ‘Model Cities’ approach, a new planning initiative was launched between the late 1970s and the 1980s, aimed at a deep physical and socio-economic amelioration of the tenement quarters. This neighborhood upgrade was carried out without demolitions or resident transfers; but rather, through allocating public resources to improve housing conditions, cultural and education services, and through a genuine community participation process [

12,

13,

14]. The last stage of planning innovations in Israel, launched in the late 1990s and up to the present, coincided with the spread of neo-liberal economic approaches and privatization tendencies in the US, the UK, and other western European counties and beyond. By then, not only had the architectural styles and the prevalent housing construction changed in Israel, but also the pre-1980 construction did not meet the modern standards against earthquakes (which occur on average every century in the region). Building regulations since 1991 have also required all new units to be built with a bomb shelter in view of consistent threats from beyond the borders. In addition, national housing policy has always favored, in line with urban densification policies in the Global North, increasing household density in order to better utilize soft and critical infrastructures and to reduce human overuse of land, water, and energy [

15,

16]. Urban densification has always been favored by Israeli governments on account of the relatively limited size of the country, the high fertility rate of its main Jewish and Arab sectors (in comparison to European populations), and the 1990s’ wave of close to one million new immigrants from the former USSR, accompanied by a few tens of thousands from Ethiopia [

17,

18].

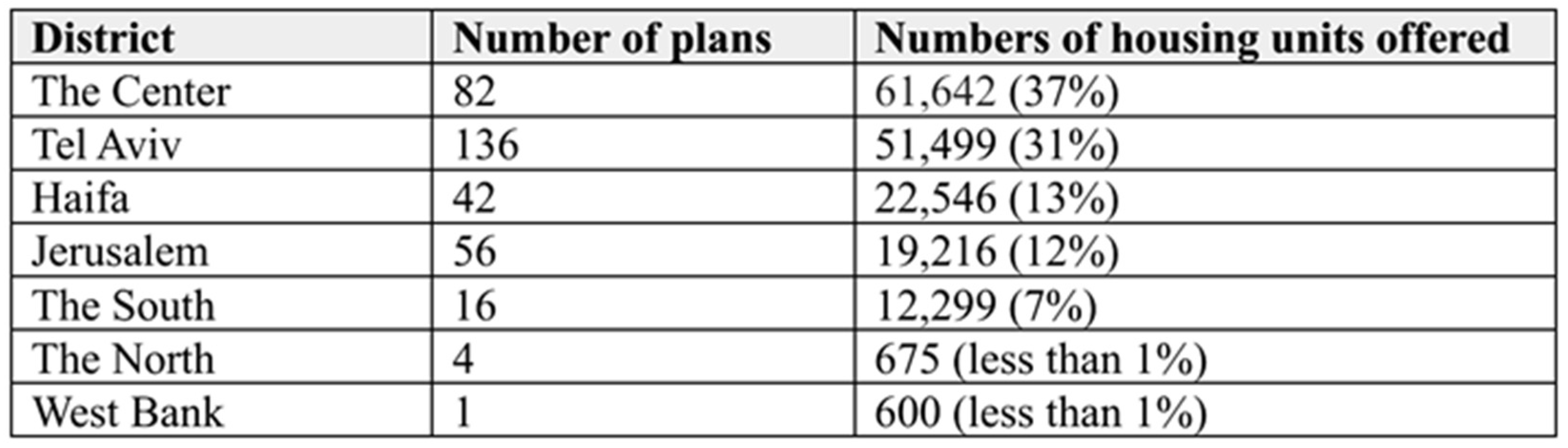

Two main urban renewal programs were therefore proclaimed in Israel at about the same time: the ‘Evacuate and Build’ program in 1998 (known as

Pinuy Binuy) and the ‘Integrated National Planning Scheme’ in 2005 (known as ‘TAMA 38’). The first program allows private entrepreneurs to demolish older building complexes and replace them with larger, modern buildings, while TAMA 38 invites entrepreneurs to extensively remodel housing units, to strengthen them against earthquakes, and to add reinforced shelter rooms and new apartment units [

19]. In both programs, the consent of the majority of the property owners is necessary to realize a project, and the public system is designed to support non-institutionalized, private market forces. In addition, in both programs, the residents are moved out for the duration of the construction or remodeling, and the entrepreneur pays for their legal representation and for alternative temporary accommodation. Conceived as a win–win deal, in both programs, the entrepreneurs add more apartments/floors in order to sell them to new residents and thereby generate a profit. However, until 2014, both renewal programs proceeded relatively slowly and involved only 4% of the overall number of buildings that were defined as requiring upgrading (approximately 50,000) [

20]. Moreover, the great majority of projects were executed in areas that were financially favored by the developers, namely in the central coastline and environs with a focus on the Tel Aviv metropolitan area—an area that, unlike the country’s periphery, is expected to be the least damaged by an earthquake. This situation has continued up to the present (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Consequently, following the study of the barriers of entrepreneurs for a more expansive application of the renewal programs, and governmental provision of incentives and tax benefits for them, a dramatic increase in the number of approved building permits has occurred since 2017. For instance, between 2021 and 2022 alone, the approval of building permits grew by 40 percent, reaching close to 131,000 housing units [

21]. While, officially, both renewal programs will terminate early in 2024, more systemic urban regeneration schemes are to be launched from late 2023, building on the experience of current achievements. The municipalities’ independence to declare entire zones as designated for renewal is expected to be increased, including their issuing of building permits accordingly. This new format is already being implemented in central cities such as Ashdod, Ra’anana, and Rishon Lezion together with considerable governmental budgetary encouragement to municipal authorities in the periphery [

21]. The basic rationale behind the present developments is the same as in the period before 2023/2024: increasing construction on built-up land and urban densification; efficient utilization of physical and soft infrastructure; meeting the standards of safety regulations; and encouraging free market activity. In this way, it is expected to add approximately a million new housing units by 2040 [

22].

This article is therefore timely because it places in the foreground both Israeli urban regeneration programs that feature the third phase of renewals,

TAMA 38 and ‘Evacuate and Build’/

Pinuy Binuy programs. The examination of these programs in light of social sustainability factors is made in retrospect, from the time of their official termination. This is, therefore, an optimal point in time not only in retrospect, but also in relation to the improvement and refinement of the future urban renewals policy, which has gained momentum in recent years. Developing a research-based approach during the consolidation of future top-down policy in this regard is important, because it opens an opportunity to increase social sensitivity and awareness on the part of national and local governments. Such societal awareness, as we shall see, is a crucial factor that stands behind the success of urban–environmental optimization and infrastructural channelization considerations. Moreover, while there are critical studies that focus on Israel’s three phases of urban regeneration schemes (e.g., [

12,

13,

14]) and a very recent series of separate case studies—each of which addresses a different aspect of the last phase of renewals and its consequences (i.e., most of the sources used in the following section)—there is no conclusive study that combines the variety of aspects, aiming at a more socially sustainable policy design. We hope the present article will thus contribute towards closing this gap.

2. A Country’s Experience: A Critical Perspective

Each phase of the US three-generation experience in urban renewals, similarly to urban redevelopment programs in other parts of the world, has always been under close examination and revision, particularly from the academic world. Within academic circles, criticism of planning intervention policies has traditionally come from the social sciences and humanities, which tend to highlight the negative consequences of regeneration projects regarding housing affordability, residential stability, and social cohesion. This section revisits a series of recent studies conducted by urbanists in theory and practice, policy makers, legal experts and medical professionals who have examined different aspects of Israel’s post-1990s’ wave of renewal programs (both pinuy binuy and TAMA 38). The examined corpus of case studies has been published in the last five years (2018–2023) in professional journals in Hebrew. Specifically, in the journal Tichnun (Planning) of the Israel Association of Town Planners (ten items), a unique local, unprecedented platform in terms of the fields of expertise represented, topical scope, and quality of research (There are only two other academic, peer-reviewed journals in Israel, as far as we are aware, with some disciplinarian affinity to that of Tichnun, that is Ofakim be-Geographia (Horizons in Geography), issued in Hebrew by Haifa University Department of Geography and Environmental Studies; and Architext of Ariel University School of Architecture, a bilingual journal (Hebrew-English) in Architecture. Publications relevant to the topic of this article have not recently appeared in these journals); and in the journal Gerontologia ve-Geriatria (Gerontology and Geriatrics) of the Israel Gerontological Society (one item). It is important to note that the analyzed corpus published in Hebrew during the past five years is extremely informative, since the new (third) phase of urban renewal programs did not gain significant momentum before 2017. Accordingly, scholarly literature regarding this phase by 2017 was relatively meagre, so that this article takes into account the bulk of the critical research regarding urban renewals as published in local professional forums.

It might be useful to learn from the variety of thematic trajectories raised in these studies, whether looking at the policy outline behind urban renewals, the implications following the execution of specific projects, or the social climates revealed through instrumental use in ethnographic research methodologies. A synoptic overview of a country-related experience in a certain socio-political, economic and environmental context can potentially consolidate our transnational knowledge of contemporary regeneration schemes and enrich societal nuances. This knowledge is an inherent product of a mosaic of situational experiences at multiscale levels of neighborhood-, city-, state-, and region-based experiments. Framing Israel’s current challenges can also assist in formulating a more socially conscious planning policy with the long-term aim of reducing, as much as possible, the extent of human distress resulting from such actions.

The main challenges and limitations as raised in this series of publications on contemporary urban renewal programs in Israel are classified into the following sub-sections: old age (one item), upper-class interests (one item), societal issues (two items), ethnicity and settlement history (five items), and policy paradigms (two items). The classification, however, is somewhat artificial as many of the referred to aspects are closely intertwined, while other aspects have not earned a sub-section because they are less prominent at present regarding renewals, such as gender issues, or heritage and conservation. This order of preference does not reflect those of the authors, who think, for instance, that some tenement buildings of the ‘train’ type are key players in the national history of habitation in terms of physical design and the then dominant socialist ideology. Religion is another important example of a sidelined issue in urban regeneration, but it has yet to be covered in the academic literature because much data are still missing. Ultra-orthodox Jewish urban communities tend to have certain spatial-demographic characteristics including voluntary segregation according to interest groups, large-sized nuclear families, high congestion, constant housing shortages, and general poverty [

23,

24]. These conditions are not attractive, to say the least, for private entrepreneurs, and thus ultra-orthodox neighborhoods have suffered, up until 2023, from a striking absence in urban redevelopment plans. Through financial compensation for private entrepreneurs, government programs are already working to change the current situation, striving for a more socially equitable distribution of the projects nationwide, especially from 2023 [

21,

22]. The challenges mentioned below point to the prominent aspects that invite further consideration in terms of designing a more socially sustainable urban intervention policy.

2.1. Old Age

The influence of the intensified wave of urban renewals on the elderly population in Israel has been investigated from psychological and medical angles during the stage of the inception of projects (i.e., dealing with a developer, lawyer, engineer, architect, etc.) [

25]. Based on in-depth interviews, the findings demonstrate great distress for the elderly, including a significant drop in mood, depression, and a general negative impact on physical health and quality of life. Repetitive symptoms have been identified by scholars: stress, anxiety, impairment of attention and concentration, headaches, and worsening of chronic pain; while all the persons interviewed were people without cognitive impairment and without depression. Scholars have not only clearly pointed to abuse, but have also identified a new syndrome, which they have called the “Urban Renewal Syndrome” [

25]. The roots of distress of the aging sector lie in the pressure exerted on them by the other owners of a building who are interested in the project; in a feeling of helplessness facing the chain of stakeholders involved in the project; and in medically determined physical and mental distress. The researchers have wondered why the reported plight of the elderly does not receive widespread public publicity and why public opinion and the media seem so far to have ignored the rights of the elderly and society’s duty towards them [

25]. This is due to the fact that during the study period (2019), approximately 15 percent of the residents of Tel Aviv, where most of the projects were carried out, were aged 65 years or older.

Among the recommendations given to enhance social sustainability and social resilience are: (a) signing with the developer only after the finalization of the details of the plan, including schedules instead of the present situation, in which a general agreement with the owners is signed first, following which the details are finalized; (b) the developer should be obliged by the authorities to provide equivalent compensation to all tenants, in lieu of each tenant’s private negotiation with the developer regarding compensation; (c) a commitment to locate equivalent housing for the elderly in the same area of the project, especially in the case of non-compliance with the schedule on the part of the developer, or failure to finish the project; (d) establishment of an ‘open line’ by the authorities for the elderly during a regeneration project, connecting to welfare officials; and (e) allowing the elderly a reduced tax upon completion of a project (i.e., Israel’s municipal tax called

arnona), which normally increases the cost of living and the neighborhood’s positive reputation [

25].

2.2. Upper-Class Interests

A glimpse at the legal arena of the renewal project provides an analysis of a series of court cases that reveal the multi-layered spatial challenges [

26] (156). Under the visible layer of struggles of higher-class residents to preserve the original character of their affluent neighborhoods, a hidden layer of exclusionary planning was revealed by the court, which it ruled against in all these cases. Between 2015 and 2021, a series of appeals against TAMA 38 schemes was submitted by owners of affluent neighborhoods (e.g., Shikun Dan in Tel Aviv, the Mosheva in Ramat Hasharon, Denia Neighborhood in Haifa, and another neighborhood in Zichron Ya’akov). According to the appellants, residents who mostly live in private buildings of one or two floors, in extremely low-density urban areas with a green rural character, renewal permits undermine the atmosphere of their properties by promoting high-density, high-rise housing. The proposed form of housing, they protested, damages their neighborhoods’ historical reputations and causes them mental distress [

26].

The appeals, however, were rejected because the judges clarified the justification for the TAMA 38/Evacuate and Build program. They emphasized the national and global target of reserving open spaces for future generations. The judges drew attention to the danger that the residents of the wealthier neighborhoods would misuse their power to cause this target to fail, and to maintain their higher status by preventing the entry of more diverse populations into the areas, who can only afford smaller apartments in a condominium. Therefore, an undesirable outcome might occur, that densification will only take place in less well-to-do neighborhoods. The judges have displayed a consistent position, according to which exclusionary planning that deprives others of building rights should not be allowed [

26]. International urban renewal policy makers can learn from this interesting legal development, sensitive to the deeper reasons behind certain preservationist approaches.

2.3. Societal Issues

Considering the urban renewal coalition between the state, private developers and property owners, an original study focused on the influence of the social interaction between the owners on the actual chance to realize the project [

27]. Using qualitative research methods based on participatory observation in owners’ committee meetings in several residential blocks in various parts of Tel Aviv-Jaffa, the study scrutinized the social interactions within these meetings. Through these months-long semi-ethnographic observations, the scholars have managed to identify the elements which could either cause the failure or promote the realization of a renewal project. For instance, while the apartment owners did not attribute special importance to the issue of strengthening the structure against earthquakes, they deemed the renewal plan a ‘planning deal.’ This means that the economic profit became a major consideration, and as such it tended to create destructive struggles and competition between the residents. In many cases, from the moment the logic of the private market entered the building, not only did the common spaces of the block (lobby, encircling yard) begin to disappear, but also the trust between the property owners that is required to execute the project dissipated [

27]. In this context of empowering the private sector, urban redevelopment has not only mainly taken place in areas with a higher demand, but also in the privileged neighborhoods of these areas. In order to address the mistrust between the parties and the mutual suspicions of maximizing profits enter many mediators (lawyers, management companies), who benefit from the breakdown of trust between the parties. For better success in the realization of such projects, more players need to meaningfully enter the arena, such as the state, the local authority, and civil society.

Another society-oriented insight is provided by a study that, this time, takes us to the end of the urban renewal process (through the ‘Evacuate and Build’ program), by analyzing the socio-spatial results of several projects in metropolitan Tel Aviv. In particular, it examined the danger of the original residents being pushed out of the renewed building and the presumed difficulties of integration between them and the incoming residents [

28]. It was found that in Israel, similarly to global tendencies, mixing between these two groups of residents can lead to conflicts. However, unlike in other Western countries, this integration is performed in Israel without state accompaniment or any administrative plan. It was also found that the extent of the departure of original owners was lower than initially assumed. This, despite the fact that privately owned properties enable relatively high economic mobility (though particular emphasis was not placed in this study on weaker populations such as public-housing residents, the elderly, or apartment tenants). These findings imply that, unlike in the mainstream critical discourse of urban renewals, this type of urban redevelopment should not necessarily be branded as a “luxury” residence, devoid of environmental and community contexts [

28]. Rather, though further research is needed on a neighborhood scale (A pioneering study employing extensive ethnographic fieldwork should be mentioned here, dedicated to the examination of the effects of socio-economic differences in the encounter between the original and the newly arriving populations as a result of urban regeneration projects in Ramat Gan, central Israel [

29]. The study managed to discern a unique integrative atmosphere between the resident groups that was named a “neighborhood climate”, in spite of disparities between them with regard to lifestyle, class, ethnic origin and demography), the study casts light on the ability of the post-renewal environment to retain a degree of connectedness and belonging among the various resident groups, and to deal with relative success with their disparities.

2.4. Ethnicity, Politics, and the Settlements’ History

Under this category, two groups of studies are brought into the fore, the first deals with the Arab population in Israel, who live in the socio-geographic periphery and are thereby largely absent from the urban renewal processes driven by market forces [

30,

31]; the second group deals with urban renewal in a prestigious area in the north of the city of Tel Aviv-Jaffa, but among a disadvantaged population of tenants (mostly of Middle Eastern Jewish extraction). This case of redevelopment led to a violent evacuation of the residents in exchange for relatively minimal compensation that the court obliged the private developers to pay to the families after many decades of conflict with the municipality [

32,

33,

34].

In an attempt to map the significant barriers that hindered, mainly until 2020, the implementation of the government’s urban renewal plans in the Arab sector, the two studies in question pioneeringly offered a practical horizon for progress. The fruit of genuine professional cooperation between government policy makers, Arab public and private agents and the community, they first identified contemporary features of Arab society in terms of family unit, education, employment, and demography [

30,

31]. Then, patterns of urban development in the Arab settlements were studied, starting from their historical nucleus in the form of privately owned lands within a dense morphological fabric without public spaces. Other identified barriers include long-standing budgetary discrimination by the authorities on the one hand and a substantial lack of trust in governmental bodies on the other hand. This is due to the political tension between the considerable Arab minority of approximately 20 percent of the total population and the state. More barriers include the perception of the land as a family asset among Arab society and its transfer from generation to generation, rather than as a business asset in the free market; power struggles between extended families; and a chronic lack of common areas. This is in addition to legal barriers such as informal land registration and transfer of lands without a written agreement, which affect, inter alia, the ability to receive loans/mortgages from banks for construction and development [

30,

31].

Governmental efforts to initiate urban renewal in this sector have been especially evident in the last three years, while the issue of adapting a statutory model that is sensitive to these barriers is still being sought. At the same time, there is recognition of each settlement as unique regarding its socio-environmental history, place-based solutions and proposed land alternatives (such as the generative project for the northern city of Sakhnin [

30]). Here, unlike the aforementioned pattern of urban redevelopment in central Israel [

27,

28], urban renewal mainly concerns public areas and requires active state intervention economically, socially and statutorily. The studies propose a list of tools intended to promote trust-building among the stakeholders, together with a deep rethinking by the government ministries entrusted with urban development [

31]. The target is to reduce spatial inequality and improve the quality of life of Arab society, a policy of the utmost importance for strengthening social resilience in the country as a whole.

The case of the Givat Amal neighborhood in the prestigious northern part of Tel Aviv-Jaffa is particularly remarkable. It demonstrates a historical conflict over the residents’ land rights, a group of families (120 in the 1950s and 14 before the last forced removals in 2021), mostly of Middle Eastern Jewish origin. The other stakeholders were the state (whose pre-state agencies brought the residents to settle there in 1947–1948 during wartime); the municipal authority (which constantly strove to evacuate them from the prestigious area for financial gain, while housing its own functionaries in private estates just across the nearby junction [

32,

35] (p. 59) [

36]); and a series of private entrepreneurs who also entered the picture in 1961 due to the privatization of public land on the hill. The privatization took place without government or municipal supervision of the tenants’ rights to the land as historically recognized by the state [

32]. The residents were therefore abandoned to the logic of the private developers, whose seven skyscrapers are now under construction. As the countless petitions and court trials over the decades fell on the shoulders of the residents, many families gave up and only a few managed to survive and continue to hold the land since the 1950s [

32,

33,

34]. This is against a background of deliberate withholding of urban amenities and infrastructure on the part of the municipal authority, and the residents’ inability to inherit or sell the land.

Analyzing the harsh consequences of Givat Amal’s redevelopment from several angles—history, geography, sociology, public policy, spatial and distributive justice, toponymic and material cultures, law and planning politics—the studies highlight the dangers in the neo-liberal climate surrounding urban renewal projects globally. They also point to the danger of minimal government intervention with regard to ethical questions and moral responsibility for disadvantaged groups. Beyond the umbrella term ‘gentrification’, the case of Givat Amal represents the political abuse of Western legal tools based on individual property rights, at the expense of a more complicated knowledge of communal property rights [

34,

37,

38]. This pattern of redevelopment is expected to feature globally in the 21st century, a pattern that illustrates the urban space “as a place of fear and hope” [

39] (p. 209); and as a composed arena in which conflict is inherent [

39].

2.5. Policy Paradigms

In studying the guiding rationale behind urban renewal programs in Israel over the ages, special attention was given to the paradigmatic change in the concept of these programs since the year 2000 [

40]. That is, from the past concept of improving the living standards and eradication of poverty in underprivileged quarters towards renewal of the housing stock through an ‘economic deal’ mainly in areas with high land value. The problematic nature of the current ‘neo-liberal’ wave of renewals that sees the private market as the sole lever for urban regeneration raises several questions: who will take care of the economically weakest groups? How will public participation be increased? What about tenants who are not the owners of the properties and with whom the ‘deal’ is not signed? How can better care of senior citizens be taken? Why has affordable public housing never been seriously considered by the municipalities [

25,

27,

30,

36,

38,

40]? Alongside these questions that emerge from the represented studies, a much broader examination of the housing situation in Israel yields a difficult impression. Since the wide-scale ‘social justice’ protest in 2011 in which the high cost of housing for young people was particularly featured (

Figure 5), the housing crisis, marked by sharp, continuous increases in real-estate prices, is still ongoing.

According to the urbanist Alex Alexander, Israeli governments have economically assumed, in a rather simplistic way, that the increase in housing prices is the result of a mismatch between the supply of housing units and their demand. Therefore, they tried to encourage an increase in the pace of housing construction and the removal of administrative barriers in the planning system [

41]. While failing to consider the speculative demand for housing, governments initiated too few (and too late) programs for affordable housing. Most of their efforts to increase the housing supply were focused on the TAMA 38 programs and rebuilding schemes to leverage market forces. As this trend of renewals constitutes an ‘economic deal’, its implementation has little effect on housing prices, to say the least. In Alexander’s opinion, despite all their statements to the contrary, Israeli governments did not care enough to invest both the political and material efforts to effectively deal with the crisis. Public housing has almost completely dried up, and there is no plan to commit capital to overcome the power of financial and real-estate stakeholders. Moreover, against the complexity of the housing market (rich/poor; center/periphery; in-use housing demand/speculative demand), well-targeted programs are required to overcome the crisis (e.g., aggressive housing supply in areas of demand and aggressive taxation of capital gains from real estate to fight speculators) [

41]. Not only has nothing been achieved in this direction, but also the planning system was weakened by the simplification of procedures to appease developers, resulting in the rapid approval (and implementation) of poor plans.

In addition, there is a need to further elaborate and diversify the present criteria for urban renewal policy evaluation on the part of Israel’s Governmental Authority for Urban Regeneration. For instance, its concluding report for 2022 [

21] is built almost exclusively on quantitative data. That is, the success of the program at the national level seems to only be evaluated based on such data, e.g., the number of housing units provided compared to previous years, the increase in building permits in percentages compared to previous years, or the degree of actual implementation of the numerical goals that were set for this year. It seems from this report that the strategic targets and their quantitative measurement overshadow other considerations; for example, within the triangle of the public authorities, entrepreneurs, and apartment owners, the apartment owners in 2022 have been strengthened with more relevant knowledge (though without reference to tenants who are not owners); the ‘refusing-owner law’ was also strengthened, that is, the percentage of supportive apartment owners needed to advance the project is based on a relatively loose majority of 66 percent (in this context, some assistance to old-age tenants is mentioned, but without further details); and only approximately one-third of the appeals (30 out of 100) submitted to the Commissioner of Owner Inquiries within this designated government authority were addressed (in most cases, with the commissioner’s decision to stop the inquiry procedure or to reject the inquiry outright) [

21] (pp. 5, 34). See also [

42] (pp. 17, 18).

3. Concluding and Recommendation Notes

This article has critically re-examined a series of recent academic studies on various aspects of the implementation of urban renewal programs in Israel since the year 2000. Special attention has been given to social sustainability considerations, beyond the environmental reasoning of urban regeneration of densification and infrastructural utility. Some lacunae have been identified regarding top-down awareness of the theory, policy and practice of social sustainability globally and its comprehensive character. Against the backdrop of the multifaceted critique regarding societal issues arising from this series of studies from the last five years (2018–2023), which is being crisscrossed with the official termination of this third phase of renewal schemes in the country (by late 2023 with extension to early 2024), the contribution of this article is timely. Recommending directions of post-2024 top-down policy refinement, this article calls for a further elaboration of the socio-ethical aspects of Israel’s urban regeneration programs, and to rethink these aspects with enhanced sensitivity.

Furthermore, because the post-2000 wave of urban renewals has gained an unprecedented momentum in recent years, just upon its official termination, there is a need for a comprehensive revaluation study that would translate key parameters of social sustainability into applicable policy. Meeting these challenges is important, especially at present, with the government’s intention to expand renewal programs to areas that are socially and geographically different, to marginalized areas, and to areas that are less financially profitable for entrepreneurs. Despite these future positive directions and plans on the part of Israel’s Governmental Authority for Urban Regeneration, we have indicated that policy evaluations on the part of this agency are mostly based on quantitative data. There is a need, therefore, to open the evaluation criteria to qualitative indicators and to more nuanced examinations grounded in Humanities and Social Sciences research though the task might be challenging.

In the West (and beyond), critical discourse on urban social sustainability in the context of urban regeneration has been crystalized over the last two decades, and country-related experiences are being shared [

43,

44,

45,

46]. Yet, only one study among the rich corpus represented in the previous section of this article mentioned, in passing, the issue of social sustainability (i.e., [

40] (p. 86); the other mentions of social sustainability so far have been made post factum, by the authors). Similarly, in Israel planning policy documents regarding urban redevelopment, particularly those of the Governmental Authority of Urban Regeneration, the term social sustainability is not mentioned at all. In the Israeli public sphere of urban management more generally, however, a fruitful cooperation between governmental, municipal, and civil society organizations (some of which are research-oriented) has already been ongoing for a decade. This cooperation actively involves environmental and social sustainability agendas together with policy making, normally at the neighborhood level. It includes frequently repeated collaboration between municipalities (Tel Aviv municipality is most prominent), the Ministry of the Environment, the Israel Green Building Council, and two leading civil-society agencies, namely the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research and the Heschel Center for Sustainability [

47,

48,

49,

50]. Building on empowering the neighborhood as a basic unit for soft intervention to enhance urban social resilience, the spheres of activity of these collaborations are focused on connecting citizens and various organizations and business; changing the urban lifestyle towards more sustainable habits; and promoting a sustainable environment by reorienting infrastructure and amenities, governmental issues, economics, public spaces, and transport.

These efforts of policy design do not yet seem to directly inform the Israel Authority for Urban Regeneration, nor to directly influence its considerations and endeavors. In the near future, a meeting between market-led urban redevelopment programs and the deep humanistic and qualitative dimensions rooted in social sustainability theory should be strived for, taking into account, inter alia, the country’s outstanding overcrowding. Continuing the current growth rate of approximately 2 percent per year means that Israel’s population will increase by 75 percent by the year 2050, and will then reach more than 15 million people [

51] (p. 7). In addition, while there is an abundant of mainstream critique (public media and academic) about failed or anti-/quasi-societal schemes of urban renewal globally, there is much less scholarly literature about successful interventions. Future research should thus be more focused on successful case studies and on their context-dependent exploration, though successes are sometimes difficult to define. As there is no formula or “recipe” to generate an often site-related “success”, future research should also be open to the ongoing development of criteria to promote social sustainability in urban environments [

52,

53,

54]. Transnational experience can be further shared and leveraged in this direction. Here, there is a potential contribution to the strengthening of community resilience and social resilience more broadly, as previous experiments with such initiative shows that their influence tends to radiate centrifugally, beyond the regeneration site itself. Moreover, each country’s experience constitutes an integral link in the chain, and dissemination of global knowledge can be used to strengthen weaker links and therefore its overall resilience.