Coping with Floods in Pikine, Senegal: An Exploration of Household Impacts and Prevention Efforts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Urban and Economic Development of Pikine

1.2. Overview of Flood Impacts in the Dakar Metropolitan Region

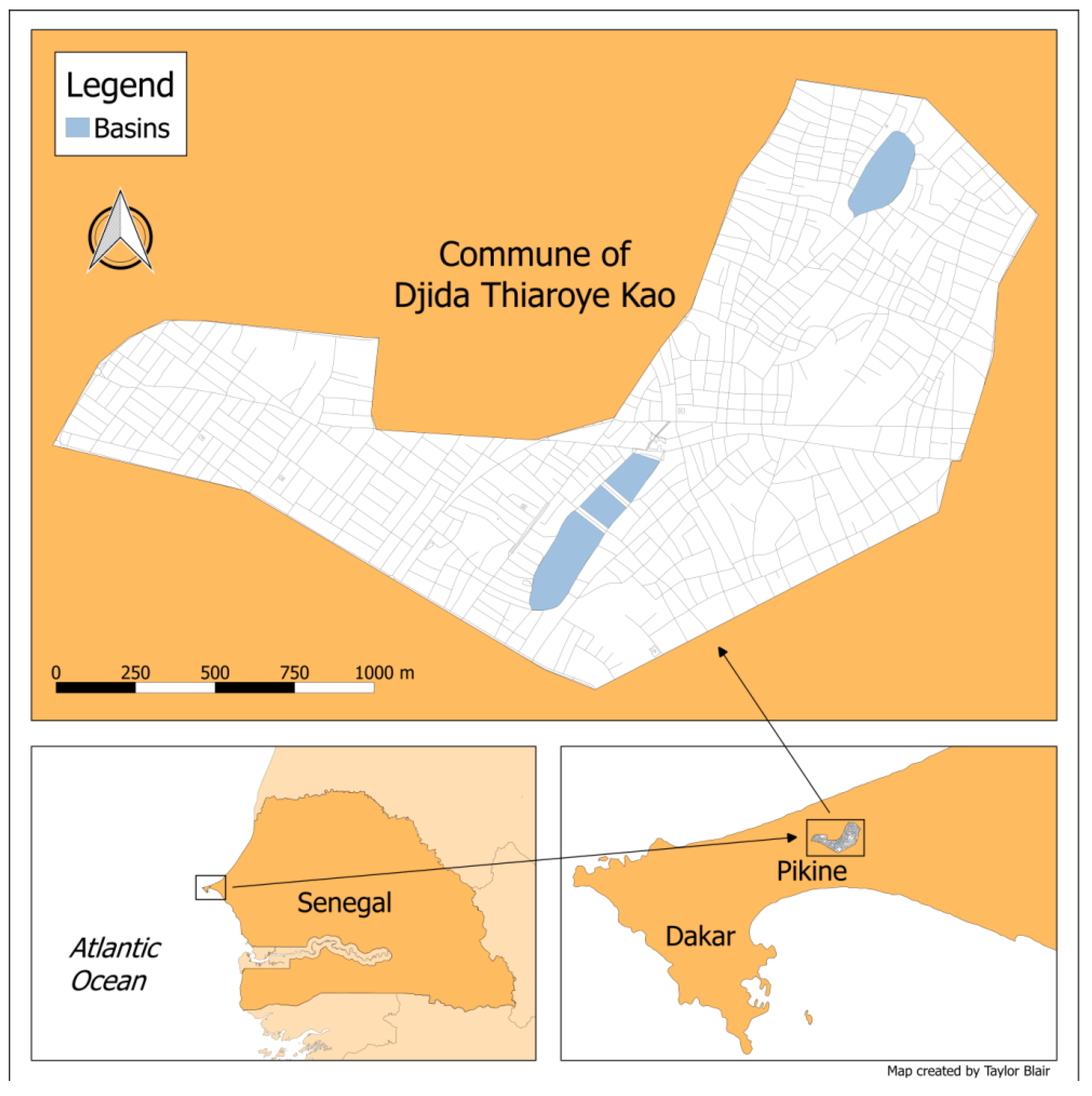

2. Study Site and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Flooding Frequency

3.2. Flooding and Economic Resilience

3.3. Flooding and Health

3.4. Effectiveness of Government Interventions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dartmouth Flood Observatory. 2005 Global Register of Major Flood Events. Available online: http://www.dartmouth.edu/~floods/Archives/2005sum.htm (accessed on 14 August 2018).

- Cissé, O.; Sèye, M. Flooding in the suburbs of Dakar: Impacts on the assets and adaptation strategies of households or communities. Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, K.; Turner, L.R.; Tong, S. Floods and human health: A systematic review. Environ. Int. 2012, 47, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongman, B.; Ward, P.J.; Aerts, J.C.J.H. Global exposure to river and coastal flooding: Long term trends and changes. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2012, 22, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilby, R.; Keenan, R. Adapting to flood risk under climate change. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2012, 36, 348–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnell, N.; Gosling, S. The impacts of climate change on river flood risk at the global scale. Clim. Chang. 2016, 134, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöschl, G.; Hall, J.; Parajka, J.; Perdigão, R.A.; Merz, B.; Arheimer, B.; Aronica, G.T.; Bilibashi, A.; Bonacci, O.; Borga, M.; et al. Changing climate shifts timing of European floods. Science 2017, 357, 588–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirabayashi, Y.; Kanae, S.; Emori, S.; Oki, T.; Kimoto, M. Global projections of changing risks of floods and droughts in a changing climate. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2008, 53, 754–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirabayashi, Y.; Mahendran, R.; Koirala, S.; Konoshima, L.; Yamazaki, D.; Watanabe, S.; Kim, H.; Kanae, S. Global flood risk under climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöschl, G.; Montanari, A. Climate change impacts—throwing the dice? Hydrol. Process. 2010, 24, 374–381. [Google Scholar]

- Kellens, W.; Terpstra, T.; Schelfaut, K.; De Maeyer, P. Perception and communication of flood risks: A literature review. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, A.; Leck, H.; Parnell, S.; Pelling, M. Africa’s urban risk and resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Red. 2017, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodman, D.; Leck, H.; Rusca, M.; Colenbrander, S. African urbanisation and urbanism: Implications for risk accumulation and reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Red. 2017, 26, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, I.; Alam, K.; Maghenda, M.; McDonnell, Y.; McLean, L.; Campbell, J. Unjust waters: Climate change, flooding and the urban poor in Africa. Environ. Urban. 2008, 20, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi, P.; Winkler, M.S.; Speranza, C.I. Flood governance for resilience in cities: The historical policy transformations in Dakar’s suburbs. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 93, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, M.; Traore, V.; Toure, M.; Sambou, A.; Diaw, A.; Beye, A. Detection and ranking of vulnerable areas to urban flooding using GIS and ASMC (spatial analysis multicriteria): A case study in Dakar, Senegal. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2016, 2, 1270–1277. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer, H.R.; Amiguet, A.; Brandvold, V.; Daouk, S.; Gueye-Girardet, A.; Hitz, C.; Ndiaye, M.L.; Niang, S.; Okuda, T.; Roberts, J.; et al. Water-related risks in the area of Dakar, Senegal: Coastal aquifers exposed to climate change and rapid urban development. In Identifying Emerging Issues in Disaster Risk Reduction, Migration, Climate Change and Sustainable Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schaer, C. Condemned to live with one’s feet in water? A case study of community based strategies and urban maladaptation in flood prone Pikine/Dakar, Senegal. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2015, 7, 534–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, S.C.; Faye, S.; Wohnlich, S.; Gaye, C.B. An assessment of the risk associated with urban development in the Thiaroye area (Senegal). Environ. Geol. 2004, 45, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, V.; Faye, S.C.; Faye, A.; Faye, S.; Gaye, C.B.; Sacchi, E.; Zuppi, G.M. Water quality decline in coastal aquifers under anthropic pressure: The case of a suburban area of Dakar (Senegal). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 172, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, P. Health impacts of floods. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2011, 26, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyani, S.; Bassett, E.M.; Talukdar, D. A tale of two cities: A multi-dimensional portrait of poverty and living conditions in the slums of Dakar and Nairobi. Habitat Int. 2014, 43, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambe-Ba, B.; Espié, E.; Faye, M.; Timbiné, L.; Sembene, M.; Gassama-Sow, A. Community-acquired diarrhea among children and adults in urban settings in Senegal: Clinical, epidemiological and microbiological aspects. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, G. African Cities: Alternative Visions of Urban Theory and Practice; Zed Books: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bigon, L. Names, norms and forms: French and indigenous toponyms in early colonial Dakar, Senegal. Plan. Perspect. 2008, 23, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, H.; Smiley, S. Comparing colonial water provision in British and French Africa. J. Hist. Geogr. 2016, 52, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, A.M. Reaching the larger world: New forms of social collaboration in Pikine, Senegal. Africa 2003, 73, 226–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericks, R.C. Doing the Dirty Work: The Cultural Politics of Garbage Collection in Dakar, Senegal; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon, T.M.; Richmond, A.K.; Shelzi, J.; Myers, G. Cultural identity in the peri-urban African landscape: A case study from Pikine, Senegal. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2017, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, O.C.; Faye, S.C.; Dieng, N.M.; Faye, S.; Faye, A. Hydrological risk analysis with optical remote sensing and hydrogeological modelling: Case study of Dakar flooding area (Senegal). Geoinfor. Geostat. An Overv. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbow, C.; Diop, A.; Diaw, A.T. Flood risk and land occupation in Dakar outskirts. Does climate variability reveal inconsistent urban management? IOP Ser. Earth Environ. 2009, 6, 332025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cissé, A.; Mendy, P. Spatial relationship between floods and poverty: The case of region of Dakar. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2018, 8, 256–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, E.E. Your Pocket is What Cures You: The Politics of Health in Senegal; Rutgers University Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hungerford, H. Material impacts of hip-hop on urban development in Dakar: The case of Eaux Secours. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2013, 5, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, R.; Reyes, R.; Matte, M.; Ntaro, M.; Mulogo, E.; Metlay, J.P.; Band, L.; Siedner, M.J. Severe flooding and malaria transmission in the Western Ugandan Highlands: Implications for disease control in an era of global climate change. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, 1403–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majambere, S.; Pinder, M.; Fillinger, U.; Ameh, D.; Conway, D.J.; Green, C.; Jeffries, D.; Jawara, M.; Milligan, P.J.; Hutchinson, R.; et al. Is mosquito larval source management appropriate for reducing malaria in areas of extensive flooding in the Gambia? A cross-over intervention trial. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 82, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbow, C.; Diop, A.; Diaw, A.T.; Niang, C.I. Urban sprawl development and flooding at Yeumbeul suburb (Dakar-Senegal). Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 2, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tempark, T.; Lueangarun, S.; Chatproedprai, S.; Wananukul, S. Flood-related skin diseases: A literature review. Int. J. Dermatol. 2013, 52, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer Walker, C.; Perin, J.; Aryee, M.; Boschi-Pinto, C.; Black, R. Diarrhea incidence in low- and middle-income countries in 1990 and 2010: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashizume, M.; Wagatsuma, Y.; Faruque, A.S.G.; Hayashi, T.; Hunter, P.R.; Armstrong, B.; Sack, D.A. Factors determining vulnerability to diarrhoea during and after severe floods In Bangladesh. J. Water Health 2008, 6, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusof, A.A.; Siddique, A.K.; Baqui, A.H.; Eusof, A.; Zaman, K. 1988 floods in Bangladesh: Pattern of illness and causes of death. J. Diarrhoeal Dis. Res. 1991, 9, 310–314. [Google Scholar]

- APA News, Senegal: Monthly Average Wage at CFA 96,206—Survey. Available online: https://mobile.apanews.net/index.php/en/news/senegal-monthly-average-wage-at-cfa96206-survey (accessed on 14 August 2018).

- Hay, M. The Planet: A Flood of Good Intentions in Senegal; GOOD Worldwide Inc.: New York, NY, USA; Available online: https://www.good.is/articles/pikine-senegal-flood-basins-living-with-water (accessed on 14 August 2018).

- Allen, A.; Dávila, J.D.; Hofmann, P. The peri-urban water poor: Citizens or consumers? Environ. Urban. 2006, 18, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, P.; Cotton, A.; Khan, M.S. Tenure security and household investment decisions for urban sanitation: The case of Dakar, Senegal. Habitat Int. 2013, 40, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Few, R. Flooding, vulnerability and coping strategies: Local responses to a global threat. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2003, 3, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi, P.; Winkler, M.; Boillat, S.; Diagne, A.; Maman Chabi Sika, M.; Kpangon, A.; Faye, S.; Speranza, C. Measuring Subjective Flood Resilience in Suburban Dakar: A Before–After Evaluation of the “Live with Water” Project. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, R. The politics of risk policies in Dakar, Senegal. Int. J. Disaster Risk Red. 2017, 26, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Flooding Frequency | Economic Impacts | Health Impacts | Government Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hungerford, H.; Smiley, S.L.; Blair, T.; Beutler, S.; Bowers, N.; Cadet, E. Coping with Floods in Pikine, Senegal: An Exploration of Household Impacts and Prevention Efforts. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3020054

Hungerford H, Smiley SL, Blair T, Beutler S, Bowers N, Cadet E. Coping with Floods in Pikine, Senegal: An Exploration of Household Impacts and Prevention Efforts. Urban Science. 2019; 3(2):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3020054

Chicago/Turabian StyleHungerford, Hilary, Sarah L. Smiley, Taylor Blair, Samantha Beutler, Noel Bowers, and Eddy Cadet. 2019. "Coping with Floods in Pikine, Senegal: An Exploration of Household Impacts and Prevention Efforts" Urban Science 3, no. 2: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3020054

APA StyleHungerford, H., Smiley, S. L., Blair, T., Beutler, S., Bowers, N., & Cadet, E. (2019). Coping with Floods in Pikine, Senegal: An Exploration of Household Impacts and Prevention Efforts. Urban Science, 3(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3020054