1. Introduction, Materials, and Methods

The digital revolution has profoundly transformed not only the way of working, or mobility in cities, but also the way of conceiving leisure, tourism, and culture. New digital technologies are turning everything into an available resource: services, products, spaces, connections, and knowledge [

1] This revolution came along with the development of Internet 3.0., and has been called “the sharing economy” [

2], “the peer-to-peer economy” (P-2-P), [

3] “the gig economy” [

4], or more broadly “sharing consumption” [

5]. Each of these terms represents an aspect of the digital platform revolution, but none completely captures the entire scope of the paradigmatic shift in the ways we produce, consume, work, finance, and learn [

1]

This paper focuses on the for-profit sharing economy in the tourism sector, through the study of different digital platform examples and their implications for urban planning, and specifically to one of the most recurrent problems: the touristification of urban areas. Touristification could be defined as a process, and the resulting state in a definite space, of relatively spontaneous, unplanned massive development of tourism, which leads to the transformation of this space into a tourism commodity itself. Tourism has been identified as one of the four production-consumption regimes affected by platform economies, along with waste, mobility, and employment [

6]. These platforms are transforming not only the way we travel but also the way we live in general, with a wide range of services available through different apps. In the tourism sector, the expansion of the platform economy, such as Airbnb, Uber or Just Eat, are notably affecting traditional transportation, tourism, and restaurant businesses, and this is rescaling the landscape of urban conflicts existing in many cities, around issues such as gentrification or social and economic segregation. This contribution aims to illustrate how platform economies in the tourism sector are changing the geography of urban conflicts. The case study is located in Valencia (Spain), a Mediterranean city in which urban tourism is a key driving force. Academic literature tends to focus research of new social phenomena, e.g., digital platforms, in big cities such as London, Paris, New York or Shanghai, whereas the literature gap in middle-sized or smaller cities around these issues is considerable. In the case of Spain, dozens of academic articles have been recently published on the topic of sharing economy and tourism industry for the cases of Madrid and Barcelona [

7,

8,

9] (Gutiérrez et al., 2017; Artigot-Golobares, 2017, Sequera, 2018), but there are almost no contributions on other territorial scales, such as Valencia, Palma de Mallorca, Málaga or Tenerife, smaller touristic cities that might also be deeply affected by these new digital platforms

To carry out these objectives, a three-step methodology was performed. Firstly, the data on urban conflicts were collected through the content analysis of regional print media. All the issues of the daily newspaper El Levante and El País published between 2014 and March 2018, were examined, in total 114 articles concerning urban conflicts with sharing economy platforms. The reason to choose this period relies on the fact that 2014 is an important turning point. In October 2014, Uber arrived in the city, and Airbnb, active in Valencia since 2010, began an important rise in the number of tourist apartments. Although there are plenty digital platforms, this contribution focuses mainly on these two, since they are the most relevant and have more implications in the tourism sector [

10]. After completing the database, a map showing the location of different conflicts arisen linked to digital platforms and urban tourism was made. Such conflicts include neighbor protests against the touristification or gentrification of urban suburbs, Uber conflicts with local taxi companies for the tourism market, and other conflicts with local hotels and accommodation chains due to Airbnb and tourist apartments in Valencia. The methodology followed to develop the database with news and the GIS treatment was inspired by Trudelle and Pelletier’s conflict research [

11]. Since the same methodology was used to build a larger database on urban conflicts in Valencia from 2002 to 2014, the analysis could include a temporal dimension to contrast urban conflicts before 2014 and the arrival of digital platforms, and from that year to the present. This analysis was also complemented with other data about digital platforms use in Valencia (namely, Airbnb and Uber), linked with the tourism sector.

2. The Emergence of a for-Profit Sharing Economy: Neoliberalizing Domesticity

According to [

2], it is possible to distinguish four main driving forces that supported the emergence of the sharing economy. The first would be undoubtedly the digital revolution with new technologies, such as web and mobile technologies, which play a critical role in building large-scale sharing communities, since they offer speed of contact and of the supply–demand cycle. Practices of sharing, renting and bartering already existed before the Internet, but it is evident that the emergence of new web and mobile technologies has accelerated and facilitated the rise of the sharing economy, enabling, upscaling and enhancing economic impact [

12]. The second driving force would be sustainability and environment defense. Both concepts are narrowly linked and people who adopt sharing practices claim to be “greener” than conventional ones, and it is an increasing demand in the tourism industry. There is a considerable interest in the sharing economy as a means of promoting sustainable consumption practices [

6].) heralded the sharing economy as a “potential new pathway to sustainability”. In times of scarcity, to share resources and assets means to collaborate for more sustainable ways of living. One of the examples given to defend sharing economy as a sustainable practice in contrast to unsustainable, wasteful and consumer capitalist economies would be the great garbage patch of plastic discovered years ago in the Pacific Ocean [

2]). Another important driving force would be the role played in recent years by the great recession. Although environmental narratives are present in sharing economy discourses, one of the key factors that explain the success of sharing economies is the possibility to save money. This is particularly crucial in times of austerity, loss of purchasing power and therefore more awareness about purchasing decisions, especially in a sector such as tourism, which is not a vital necessity. According to [

13], the success of digital platforms in the tourism sector, such as Airbnb, is due to the possibility to access to affordable tourist accommodation for middle classes that lose purchasing power during the crisis, in contrast with average higher prices in conventional hostel or hotels. This digital platform permitted the continuity of a high level of consumerism in tourism and travel sectors, despite the economic crisis. Some studies find that consumers who use Airbnb stay on vacation longer than they would if they stayed at a hotel, and some guests would not have gone on a vacation at all without access to the lodging platform [

1]. Finally, the fourth driving force would be the community. According to [

12], the network paradigm can be seen as a re-enactment of the ancient concept of community. Online connectivity facilitates offline sharing and social activities, allowing direct contact among people who live in the same area but do not interact. Many authors celebrated the arrival of the sharing economy as a claim for creation and restoration of the commons, following Ostrom’s ideas on assets and resource management beyond public or private models [

14,

15]. The sharing economy would enable people to manage assets and resources organized in communities. In the tourism sector, there is a wide range of digital social networks that promote finding travel partners, getting more informed about every single detail of a tourist destination, and find even a local restaurant. All these webs are based on the creation of different digital communities that focus in a definite aspect of the tourism experience: a destination, accommodations, best restaurants, sightseeing, local culture, etc.

A critical point in the sharing economy is the shift from ownership to access to services and goods, such as cohousing, car-pooling or crowdfunding. This shift characterizes a new era or age in which “you are what you can access” [

16]. The age of access [

17] describes how markets are making ways for networks, and ownership is steadily being replaced by access [

17]. According to this author, in the rise of the age of access, suppliers hold on to property in the new economy and lease, rent or charge an admission fee, subscription or membership dues for its short-term use [

17]. The emergence of the digital platform offering a wide range of access to different services is a good example. While cheap, durable goods will continue to be sold and bought in the market, more costly items such as appliances, automobiles, and homes increasingly will be held by suppliers and accessed by consumers in the form of short-term leases, rentals, memberships and other service arrangements [

17], in which the tourism sector is already being one of the most affected. It is not a coincidence that today the most powerful digital platform businesses, such as Uber, Cabify, Airbnb or Blablacar are just focused on housing and transportation, two critical aspects for the development of tourism industry. For other authors instead, this shift is a broader cultural change “from generation me to generation we” [

2]. They conceive sharing economy as a new and more sustainable way to meet needs and wants [

14] (Buczynski, 2013) with a strong belief in the commons, giving the example of the copyleft creative commons permissions for publishing, as an alternative to traditional copyright permissions [

2,

14] considered sharing economy even revolutionary, a new vision that turns consumption-obsessed society into an economic democracy, a total paradigm shift in how we produce, consume and govern [

14].

Some other authors notice some problematic issues concerning sharing economy, especially considering whether a sharing economy community works for profit or for solidarity reasons [

1,

13,

16,

17,

18]. According to Alonso [

13], many cases of the so-called sharing economy began with altruist purposes, but are really examples of ruthless egoism. Tom Slee’s book “Whats yours is mine”, an acid criticism on Botsman and Rogers [

2] (2010), stated that the most significant examples of what used to be called the “sharing economy” are really giant corporations pursuing monopoly power and the “sharing” in the Sharing Economy has been reduced to simple market exchange [

18]. According to this author, the appeal of a bottom-up, personal, community-driven alternative to traditional corporations have fizzled: we are left with Uber, a company financed by high-net-worth investors via Morgan Stanley and by Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, and Airbnb, by some measures the largest hotel company in the world [

18]. It is clear that the sharing economy concept has become an umbrella for different practices that include for profit and not-for-profit economic practices, in which a variety of digital platforms, associations, social movements, and Internet activists play a role.

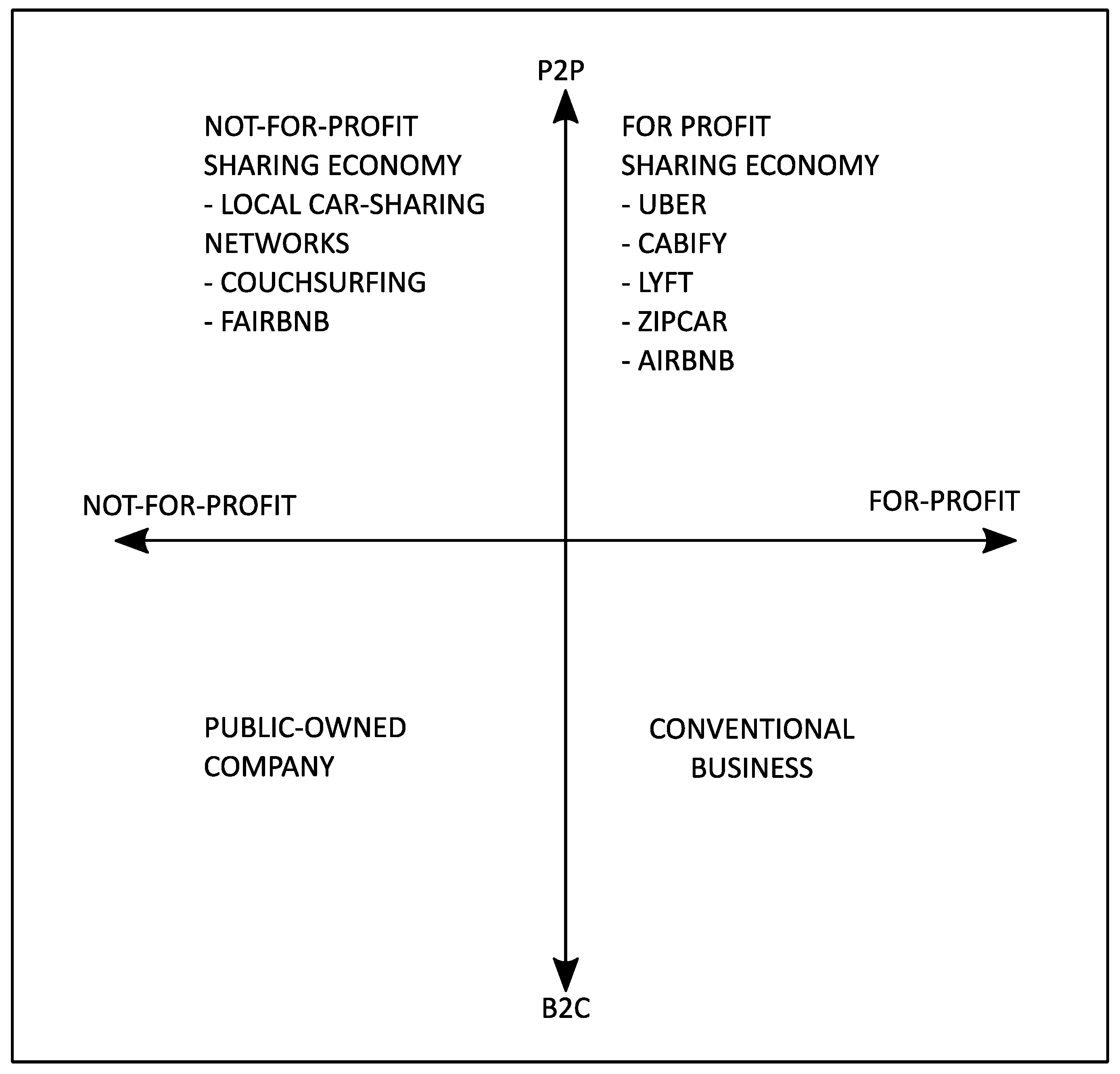

Figure 1 summarizes this variety.

A clear distinction can be made, according to [

13], between sharing economy (peer-to-peer) and conventional economy (B2C, business-to-consumer). Apart from that, the “for-profit” line divides those organizations that are contributing to the commodification of sharing or collaborative economies, to others that operate under a clear altruist, or sharing cost purposes. In the tourism sector, some alternatives are local car-pooling networks for mobility and Couchsurfing the “Fairbnb” project for accommodation. The space between not-for-profit top-down oriented practices following classical business-to-consumer, or rather an institution-to citizen classical model, is the “ruins of the welfare state” [

13] that still today offer some services based in public-owned companies. According to Srnicek [

19] for-profit sharing economies through digital platforms are just another phase in the long history of the capitalist mode of production after the 2008 crisis restructuration. The platform has emerged as a new business model, capable of extracting and controlling immense amounts of data, and with this shift, we have seen the rise of large monopolistic firms [

19] This new model business is just a new form of capitalism, a crowd-based capitalism, a sharing economy based on the peer-to-peer commercial exchange that may supplant the traditional corporate-centered model [

20] Rather than sharing economies, digital for-profit platforms should be labeled just platform capitalism or platform economies.

The distinguishing characteristic of modern capitalism is the expropriation of various facets of life into commercial relationships [

17]. Today, with the expansion of digital platforms, every aspect of the daily routine, a tourism experience included, has become a purchased affair and an increasing commodification of all human experience. Few industries are exempt from potential disruptive change within the sharing economy [

16]. A huge range of different digital platforms offers convenience services, as

Figure 2 shows. Activities traditionally embedded in the family sphere, such as childcare, food or even pet care, are today possible to cover by different platforms, such as

Bubble or

Bambino that offer babysitters by the hour,

Just eat or

Deliveroo that permit ordering food to be delivered in less than 40 min, or

Dogbuddy, offering different services of accommodation and care for pets. Even personal relationships appear today a lucrative business for digital platforms, such as

Meetic or

Tinder, that facilitate the possibility of flirting or finding new friendships without leaving home, or even meeting new people in a tourist destination when traveling. Finally, second-hand economy platforms have developed a new on-line market of shareable items. A majority of consumer goods can be understood as having excess capacity, including houses, cars, boats, houses, clothing, books, toys, appliances, tools, furniture, computers, etc.; all these items provide the consumer with an opportunity to lend out or rent out their goods to other consumers [

21]. Over 10,000 new platform companies have sprouted and mushroomed in less than a decade [

1].

Tourism is obviously not an exception and today, all the aspects surrounding travel, including accommodation, transportation, and cultural, sport or leisure activities as well as meeting local people to make the journey more “authentic”, are services provided by different for-profit digital platforms. Even potential services needed during the journey, such as cleaning the home, watering the plants, looking for the pets, walking the dogs, taking care of children or relatives, can be provided by different specialized digital platforms. Apps such as Airbnb permitted the expansion of tourism apartments but through a short-term rental model, instead of the traditional model of property-owning, the same case as Uber with urban mobility. However, the emergence of digital platforms has led to different conflicts.

3. Results: Tourism and Digital Platform Conflicts in Valencia

Valencia is today the third most important city in the country, with over 800,000 inhabitants, and a metropolitan area with more than 1.5 million. Tourism and real estate sector were for years some of the most important economic activities. Thus, the financial crisis heavily affected the city and was one of the causes why in 2015 local elections, for the first time since 1979, a coalition of left-wing parties won these elections. This coalition presented a wide range of new policy projects to manage social problems, such as house evictions, urban poverty, unemployment and other consequences of the economic crisis. Nevertheless, new challenges emerged from 2015, especially important the touristification of the urban space and the arrival platforms in the tourism sector [

22]. These new challenges led to a completely new scenario in a city in which there were not local regulations for platforms, such as Airbnb, Uber, Cabify or similar [

23].

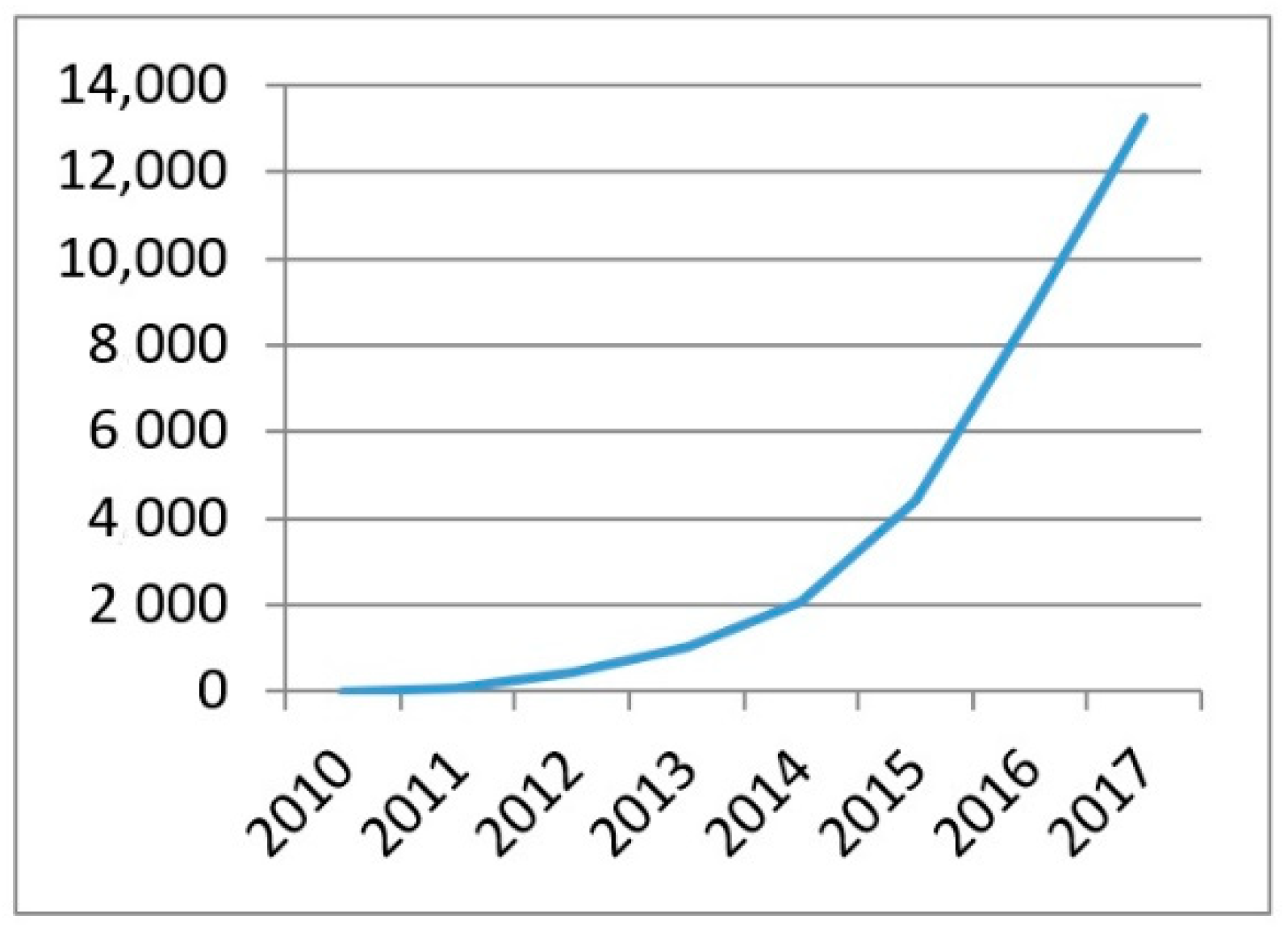

This is one of the reasons that, despite the crisis, tourism marked historic records in Valencia in terms of tourism arrivals in Spain. According to

Figure 3, short-term rentals in tourism apartments had an increase of more than 30% some months compared to the same period the previous years, whereas accommodation in hotels less than 7% [

24].

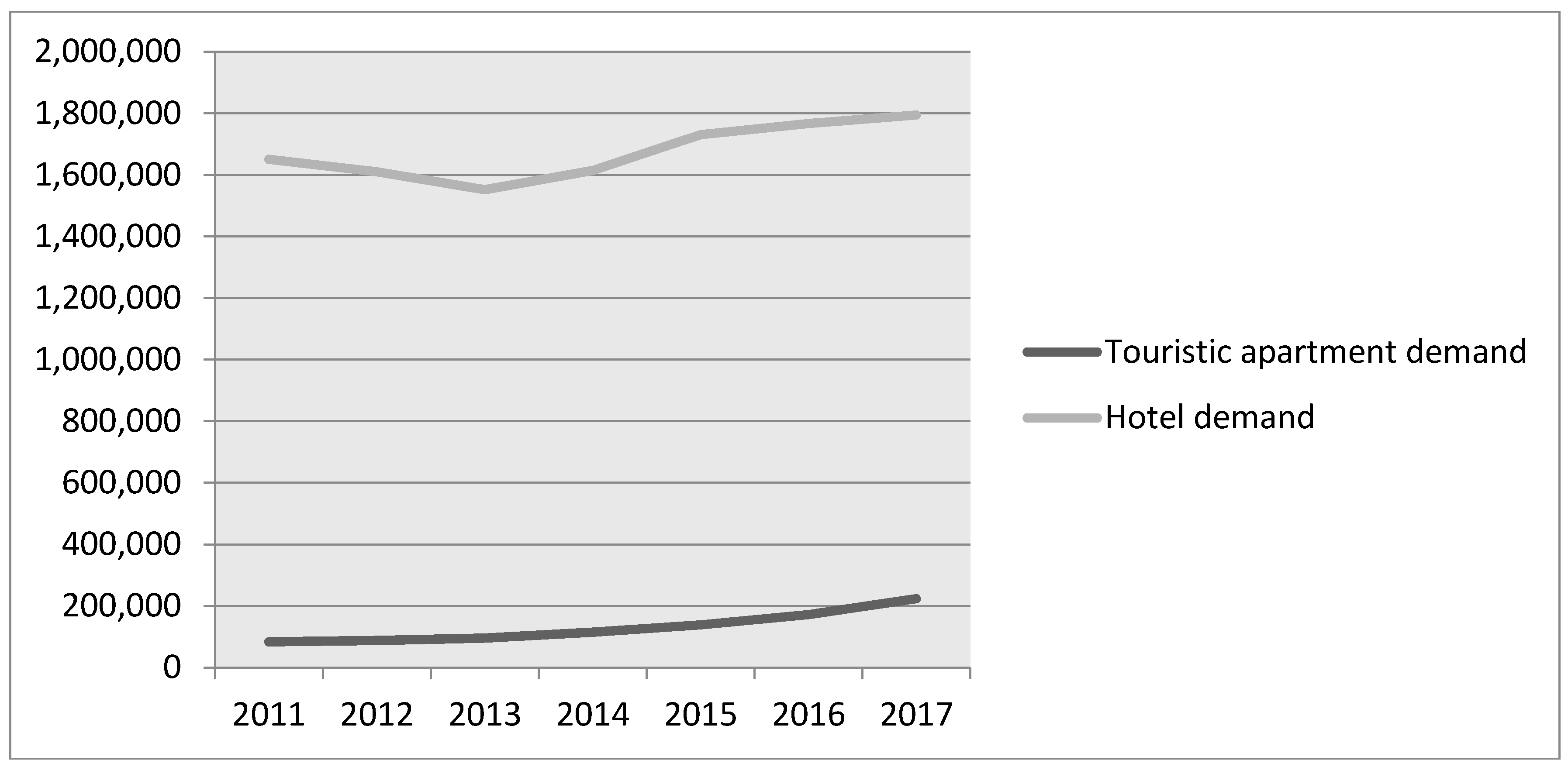

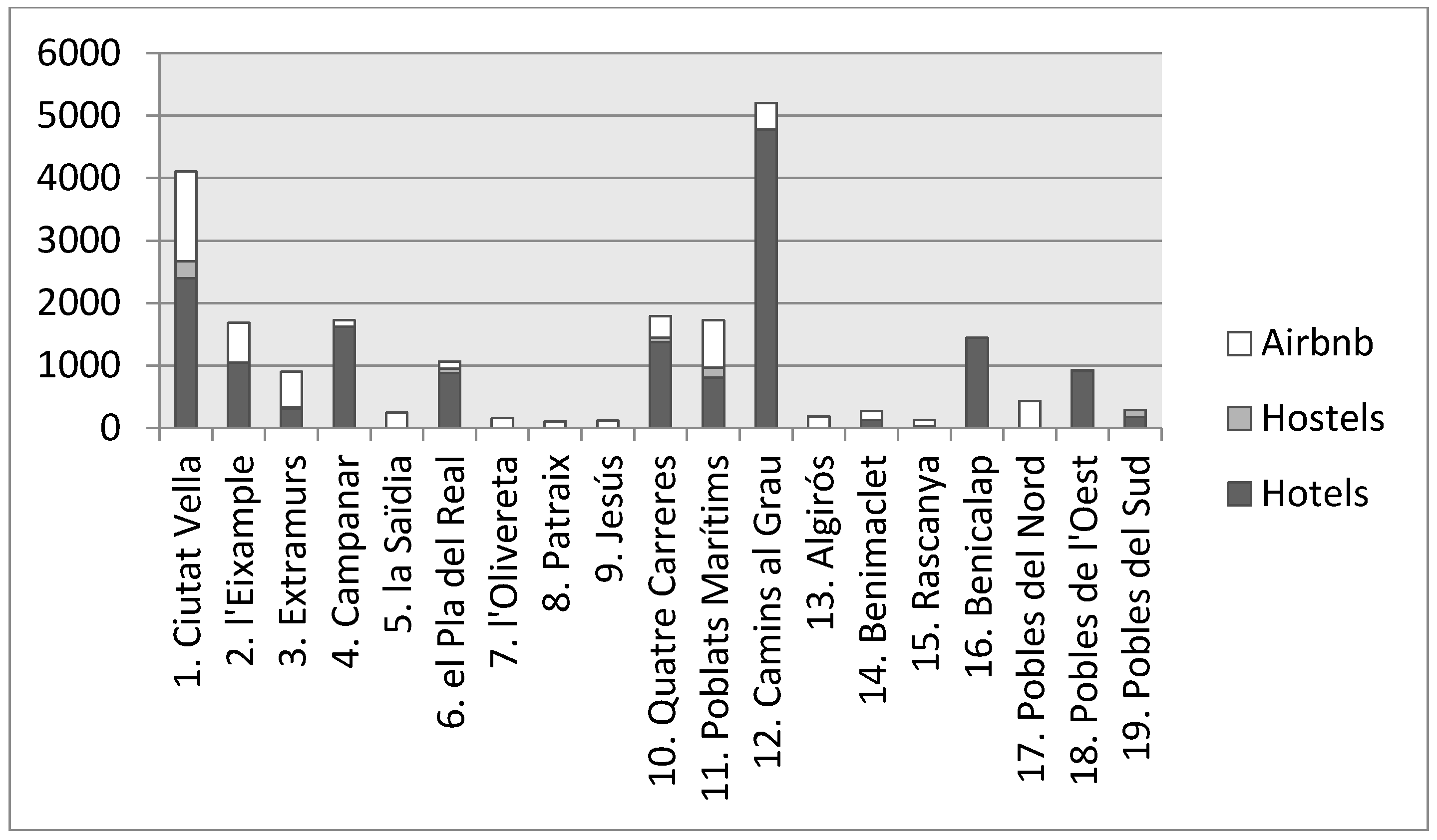

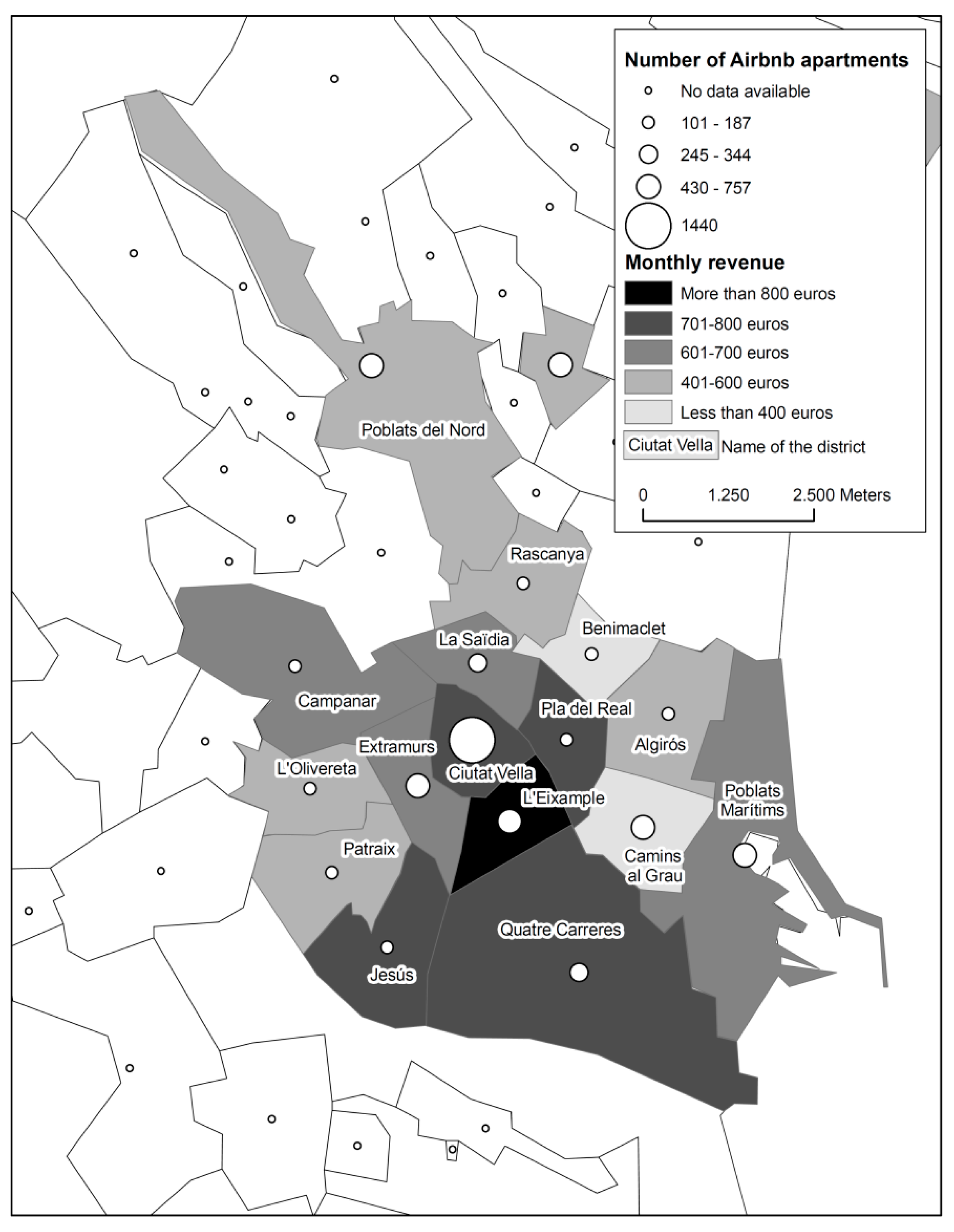

Figure 4 shows the evolution of tourist demand in hotels and apartments in the last years in Valencia. Hotels continue to be the preferred accommodation option by the vast majority of tourists and concentrate today 71% of beds. Nevertheless, the growth in the number of apartments listed in Airbnb is spectacular, with an average annual increase of 200% and, in some central districts, such as Ciutat Vella or Extramurs, Airbnb offer is bigger than traditional hotel and hostels, as well as in the beach district of Poblats Marítims (

Figure 5). These are the tourist hotspots in Valencia, where Airbnb is beginning to win the war against traditional accommodation options, but, even in less tourist areas such as Saïdia or Poblats del Nord, Airbnb is the only tourist accommodation possibility today. It is important to note precisely the change of trend in the years of the crisis: Hotel accommodation dropped between 2011 and 2013, but Airbnb offer increased notably those years (

Figure 6).

Transportation follows a similar trend to the popularization of the Internet and digital platforms: in the last two years, the arrival of tourists by flight represented more than 80% of the total, while car and train only represented 15.7% and 0.4%, respectively. There is a clear trend towards the increase of arrivals by flight and the decrease of arrivals by private car [

24]. The traditional mobility model of sun and beach tourist coming by car to Spanish beaches from their origin, mostly Britain, France, and Germany, is being replaced by a new one which combines low-cost airlines with short-term car rentals. Traditional urban transportation means such as taxi is in crisis since the arrival of Uber. Uber and Cabify driving permissions are rising dramatically (

Figure 4). Only in 2017, Uber licenses boosted from 600 to 2000, a 333% increase in only one year [

25], whereas almost 100 taxi licenses disappeared [

24]. Today, there are in Spain 5890 driving licenses for digital platforms and 67,089 taxi licenses, 1% less than in 2012 [

24] but in some touristic cities such as Málaga, driving licenses linked to Cabify and Uber represent already 20% of the overall, 14.2% in Madrid [

25].

This shift towards digital platforms has already had an impact on the geography of conflicts in cities like Valencia.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show the main results of the carried out research on conflicts linked to tourism.

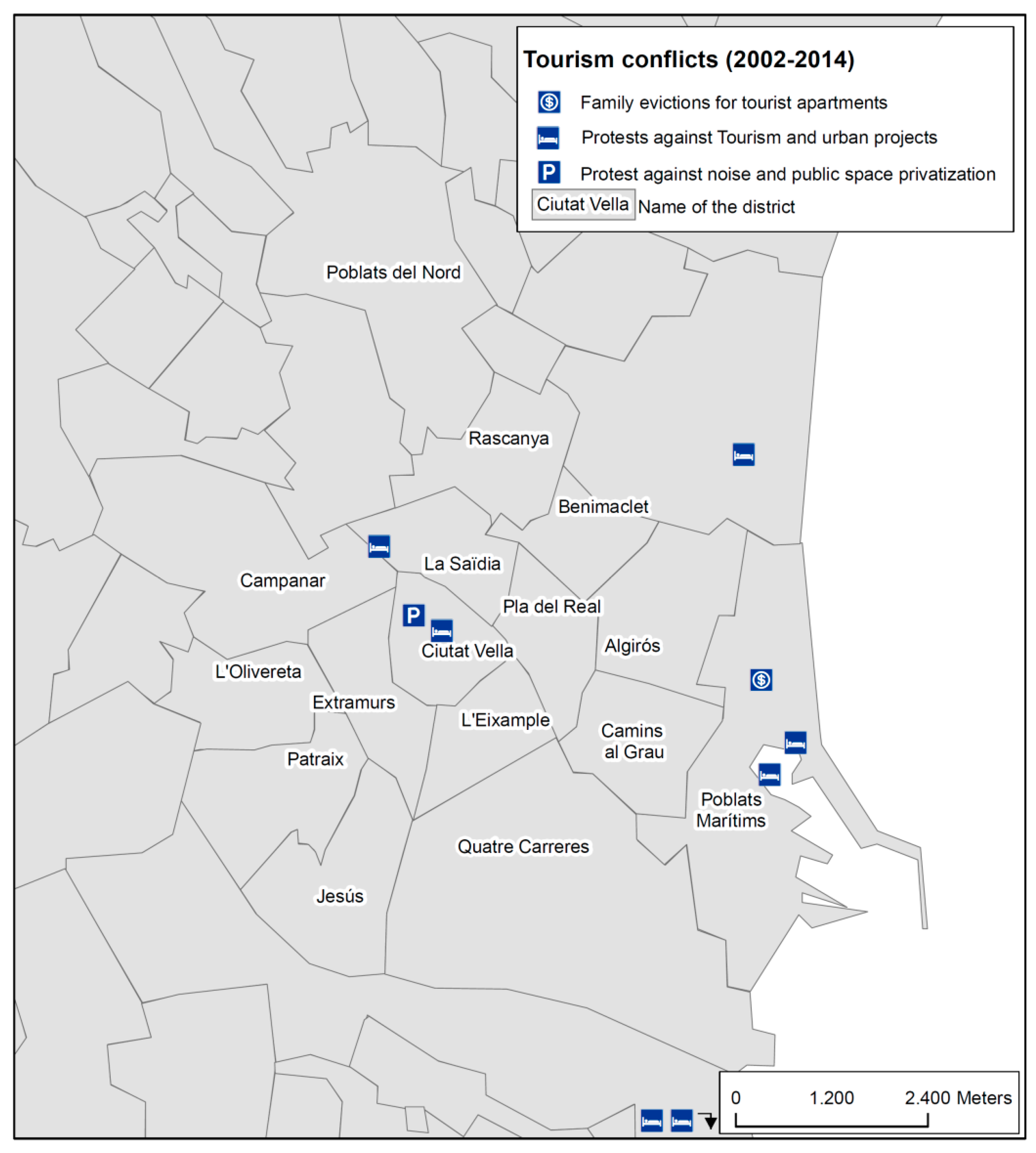

Figure 7 show conflicts between 2002 and 2014, based on a conflict database from which tourism-related conflicts were extracted [

28].

Figure 8 covers the 2014–2018 period as a result of the database on conflicts linked to tourism issues in the city of Valencia.

Despite the variety of digital platforms with public contestation, only conflicts related to tourism are included in

Figure 8.

Figure 7 shows conflicts emerged in a historic period subdivided into the economic boom until 2007, and the financial crisis from 2007 to 2014. The majority of conflicts represented here began as a result of tourism and urban development projects, such as hotel, restaurants or tourism apartment projects. Indeed, the most intense conflict in this period was the Blasco Ibáñez Avenue project, an urban mega-project that implied the eviction of more than 1600 families from the poor neighborhood of El Cabanyal, to construct more than one thousand apartments and tourism apartments and hotels. The only conflict linked to noise and tourism emerged in the central district of Ciutat Vella, which is one of the most long-lasting conflicts in the city. Although the whole period was intense in protests and conflicts, with more than 80 [

28], only nine, less than 10%, were tourism-related.

Figure 8 shows in total, 14 tourism-related conflicts reported through local media, all of them linked to Airbnb or transportation digital platforms, such as Uber or Cabify. Some examples of conflicts mapped here include the confrontation between the Entrebarris neighbor association in Russafa and a private company that bought an entire building and evicted seven families in the Russafa suburb, a very similar case in the Saïdia suburb, or the confrontation, even with physical violence, between taxi drives and Cabify and Uber drivers in tourism hotspots such as the main train station, or the High Speed train station. The other two types of conflicts represented in the map consist of a series of neighbor protests and actions against the touristification of some suburbs, and its consequences, namely more noise and widespread increase in tourism land-uses (hotels, restaurants, pubs, hostels, and of course, tourist apartments). Obviously, the stakes at conflict are not only tourism-related digital platforms such as Airbnb or Homelidays that threaten traditional tourist accommodation markets as well as the management and growth of the tourism sector in the city, but undoubtedly digital platforms are a key issue in this type of conflicts.

The ensemble of conflicts represented here could be divided into three categories, according to the source or interest at stake: land-use conflicts, land revenue conflicts, and mobility conflicts. In the first type of conflicts, the use of land and public space is the main ground for social mobilization. These conflicts are linked to urban projects in the 2002–2014 period, and later to the noise generated by tourism, as well as the privatization of public spaces, such as squares or streets. Neighbors in some suburbs feel invaded by tourists and even routine activities such as shopping or moving by public transportation become sometimes a difficult task. The second type of conflicts relate to revenue prospects generated by tourism activities, basically accommodation, against the right or will of the local population, to remain in their rented houses and to live in a suburb with facilities for their inhabitants and not only tourists. This type of conflicts is dominant in the 2014–2018 period.

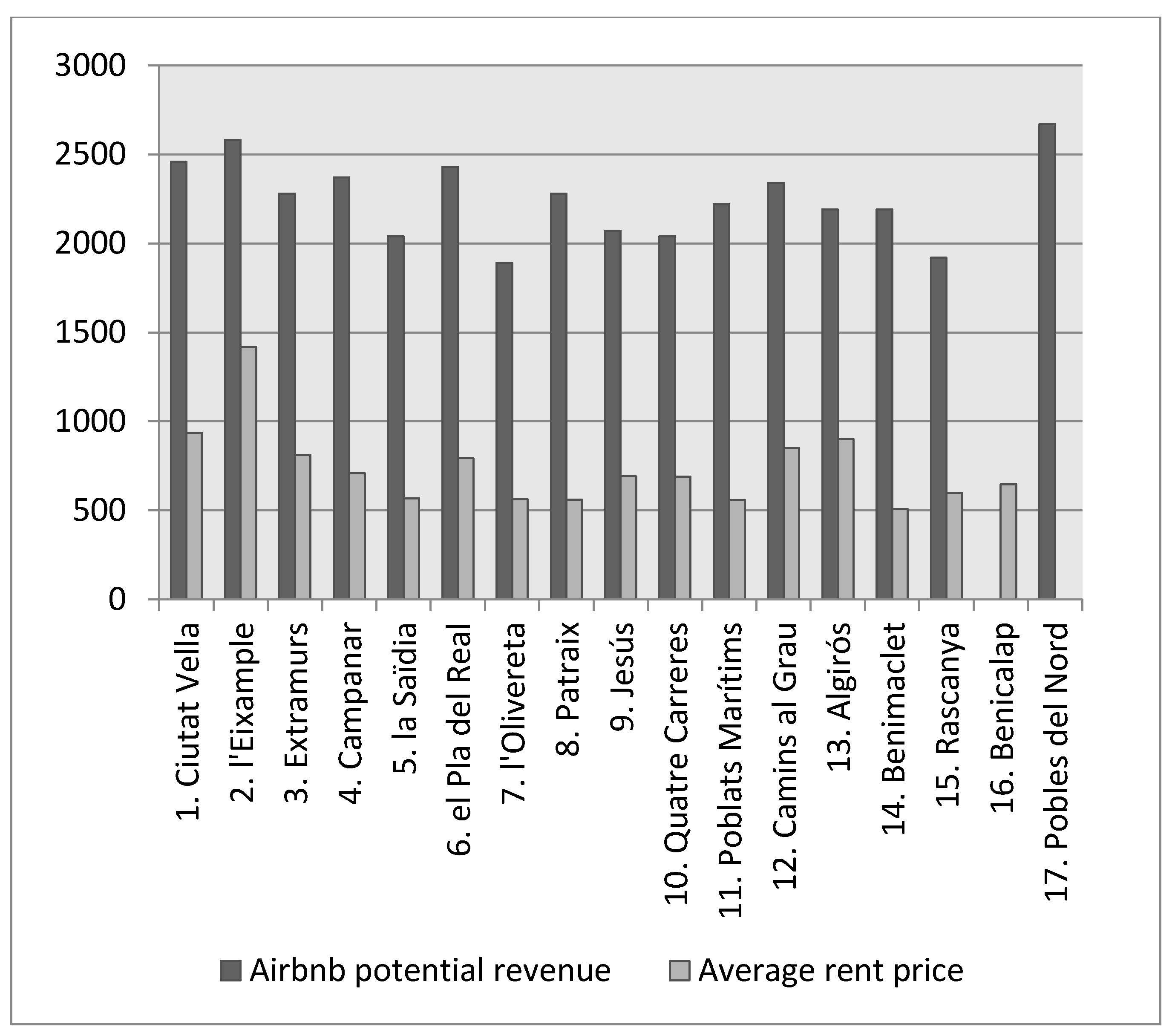

Figure 9 shows Airbnb average monthly revenue per district, according to real data [

27]. Tourist districts have a high monthly revenue of more than 700 Euros and L’Eixample even more than 800 euros. These data are relevant, since they show the average revenue, taking into account the days in which tourist apartments or rooms remain empty, or low season months. In contrast,

Figure 10 compares Airbnb potential monthly revenue (a full-booked month in a tourist apartment), with average rent prices in each suburb. Today, an owner can obtain between 200% and 500% higher potential revenue in Airbnb compared to rent in the conventional housing market. This potential revenue is quite real during the high season, in which the housing and hotel occupation rate is 100%. This is one of the main reasons local owners, but especially international investment funds, are interested in housing markets in cities such as Valencia, and why entire buildings are being evicted to be transformed as tourist apartments to be booked via an app. A proof of how Airbnb is becoming a very profitable professional business, rather than a sharing economy example, is that today in Valencia 61% of hosts are multi-listing, some with more than 10 apartments under the same profile and 65% offer entire apartments, and only 35% private rooms in shared flats [

27]. These data show how for-profit platforms have co-opted what began as a progressive, socially transformative idea, e.g., home-sharing. According to Slee, this shows the great shift in sharing economy: what started as an appeal to the community, person-to-person connections, sustainability, and sharing has become a Wall Street and venture capitalists extending their free-market values into our personal lives [

18]. The tourism sector in Valencia is a good example of digital platforms as new businesses with considerable revenue. Today, Valencia multi-listing hosts possess 4590 properties in Valencia, 58% of the total [

27]. The majority of these multi-listing hosts are big corporations, such as Friendly Rentals an international rental company with properties in 20 different cities in Europe, and, in the case of Valencia, this corporation has already over 30 apartments in Airbnb [

29,

30,

31].

Finally, mobility conflicts relate to disputes against traditional transportation operators, basically taxi drivers. Cabify and Uber retain up to 25% revenue for each service and their tariffs are between 10% and 60% higher than average taxi tariffs in cities such as Madrid [

31]. However, the potential revenue for Cabify or Uber drivers is higher than conventional taxis, since they have a potential demand that covers the whole city through the app, whereas taxis work mostly looking for potential customers while driving, which is much more limited in terms of potential demand. According to [

32], Uber drivers work fewer hours and earn more per hour than traditional taxi drivers, even after accounting for their expenses. Apart from that, the difficulty that entails obtaining a taxi license, discourages many young professionals that find in Uber and Cabify interesting alternatives.

4. Discussion. Touristification and the New Geography of Conflicts: The Case of Valencia

The digital economy is becoming a hegemonic model: cities are to become smart, businesses must be disruptive, workers are to become flexible, and governments must be lean and intelligent [

19]: 8). Within the tourism sector, the emergence of digital platforms offering different services for traveling, such as Airbnb or Uber, is reinforcing the already active landscape of conflicts around tourism and the city [

34], and is a step forward to the total commodification of every aspect and minute of a travel experience [

1]: 147). Cities such as Berlin, Venice, Florence, Paris or New Orleans already had important conflicts around the touristification of urban centers since at least the 1990s [

34]), so the digital revolution only intensified an already vivid landscape of urban conflicts, mostly between tourism widespread increase and the local population. In countries such as Spain, tourism sector was completely liberalized long before the arrival of Airbnb or Uber [

35].

Madrid, Barcelona or Valencia had before the financial crisis a vivid landscape of urban conflicts, in many cases, linked to the economic boom, urban speculation and the construction of urban mega-projects and mega-events [

28], as can be seen in

Figure 7. A protest cycle ended in 2011 with the financial crisis and the important social mobilizations of the indignados and 15M movements [

28], leading to a new political cycle in which new political parties such as Podemos (We can) or Ciudadanos entered the political arena. In this period, from the 1990s to 2011, many conflicts linked to the construction of urban mega-projects to attract tourism were an important source of conflicts, such as the Formula 1 project in Valencia, the failed Eurovegas project in Madrid, or the High-speed train to the airport in Barcelona [

36]. Nevertheless, conflicts arisen in the post-crisis period from 2014 show a very distinctive landscape: more conflicts, often located in the city center, and linked to the use of the urban space (public space, housing, and mobility), rather than the construction of the urban space, as in the previous period. Whereas the grounds for protesting in this period were linked to heritage, environment protection and housing rights [

28], with the emergence of digital platforms linked to tourism, the situation has dramatically changed.

Academic literature and media have focused their attention on the possible negative impacts and hence the main possible causes for conflict because of the irruption of for-profit digital platforms. These impacts can be summarized in four different areas: labor conditions; lack of legal and fiscal regulations; gentrification and touristification; and environmental impacts.

Labor conditions and deregulation in digital platforms is one of the most intense discussions in media and academic literature [

37]. The main worry is that absent regulatory controls, the platform will lead work to be so app-driven that the internal logic of full-time employment, job security, and worker rights will collapse [

1]. Some critics consider for-profit platforms as architects of a growing “precariat”, a class on the precarious edge of economic security, and argue that the impetus for sharing is not trust, but desperation [

37]. The employment status of the providers on these digital platforms remains uncertain because they are not considered employees of a definite corporation. Beyond these problematic issues, for [

1], the rise of the platform is partly due to the decline of full-time, long-term jobs and cycles of high rates in unemployment and also represents a shift in preference, as many people entering the labor market today prefer flexibility and control over their work-time [

1]. In the case of Valencia, this is a very important discussion in the legal and political arena, since workers for digital platforms do not have a definite status within the labor regulations.

Concerning the lack of legal and fiscal regulation, the legal battles often turn on how to define the platform business: the still unclear big question is whether digital companies are just service providers or brokers of individualized exchanges that have been running against existing regulations [

18]. For some authors, digital platforms are presenting a great challenge for consumer protection laws, safety, and health regulations, business permits and licenses, property and zoning laws, and financial services regulations [

18]. Sharing economy platforms, in particular, Airbnb and Uber, are critiqued for transferring risk to consumers; creating unfair competition; establishing illegal, black or grey markets; and promoting tax avoidance [

6]. In contrast, digital platforms claim to be operating in outdated legal frameworks that are really guild protectionists, unable to capture its new business model or even fit the new economy. They add, in cases such as Uber, that they are merely an app and network not owing assets [

38]. Digital platforms are introducing new forms of private regulation: reviews, ratings, and social network recommendations. These features can combine to provide alternatives to traditional regulation, as for example quality standards assigned to a hotel in terms of stars is today less trusted than Booking.com ratings and reviews [

13]. Fiscal regulation is another unsolved issue in Spain, which is in the center of the conflict between digital platform and corporations. A primary concern of local regulators involves whether the platform economy should be taxed at the same levels as competing industries. Digital platforms consider taxation as another regulatory challenge: “there were laws created for businesses, and there were laws for people. What the sharing economy did was creating a third category: people as businesses” [

39].

The environmental effects associated with the sharing sector are also complex. Sharing is thought to be eco-friendly and a more sustainable form of consumption [

6] because it is assumed to reduce the demand for new goods or the construction of new facilities (in the case of hotels or shared spaces). Despite these widespread beliefs, there is not yet empirical evidence on these claims [

21]. To determine full carbon and eco-impacts, it is also necessary to analyze all the changes that are set in motion in the system as a result of a new sharing practice [

37]. For example, if the sale of a household’s used items creates earnings that are then used to buy new goods (“rebound effect”), the original sale may not reduce carbon emissions or other environmental impacts [

21]. Furthermore, according to the evolution of Uber and Cabify in the transportation sector, some cities such as Barcelona could be facing a situation of heavy pollution and traffic saturation [

40]. Only in this city the number of Uber and Cabify vehicles could increase to more than 3000 units in the next years, in a city already with important traffic, parking and pollution problems [

40].

These three issues are indeed present in the discourses of actors in the different conflicts represented in Valencia. Obviously, taxi associations attack Uber on Cabify because of their lack of a clear and fair labor and fiscal regulation, but the rest of the conflicts sees in the arrival of digital platforms offering lodging and transportation services to tourists, rather than these problems an old one: gentrification. Gentrification and touristification is the main negative aspect highlighted by neighbors in Valencia, who claim new zoning laws to keep residential areas quiet, clean and safe, and public housing policies to avoid family evictions for tourist apartments. An example of zoning law is the noise-free areas, which is a legal concept already present in two suburbs in the city, that had conflicts due to the noise from bars and pubs. Gentrification and touristification often come together, since tourism often follows urban gentrifiers [

41]. Touristification or tourism gentrification can be defined as the transformation of a working-class or middle-class neighborhood into a relatively affluent and exclusive enclave marked by a proliferation of corporate entertainment and tourism venues [

42]. This concept brings out the dual processes of globalization and localization embedded in urban redevelopment, since tourism is characterized by international global actors (digital platforms included), while at the same time investing at the local level by developing local culture, products and places for consumption that will appeal to visitors [

41].

Tourist behaviors and markets have considerably changed during recent years. Boundaries between tourism and locals have become increasingly blurred [

43]. International tourists seek authentic local experiences, “exploring” ordinary but lively and diverse neighborhoods and visiting cafés, bars, and markets that were previously almost exclusively frequented by locals [

43]. This quest for “authenticity” of local life, as opposed to the tourist hot-spots and designated attractions, combined with the ability of transnational elites to technically, socially and economically live their life in selected places around the world and an “elective affinity” between tourists and the upper class, have considerably impacted not only the city centers but also on the peripheries [

41]. This shift has impacted profoundly in the geography of urban conflicts. As explained above, the 2002–2014 period is marked by conflicts around urban mega-projects willing to attract tourism to definite spots that are conceived and designed as a tourism product (Formula 1 circuit, luxury hotel projects, and port redevelopment plans). However, after the crisis, this new pattern is consolidated: the local lifestyle is turned itself into a tourist commodity. The quest for authenticity, “exploring” genuine bars and suburbs rather than “visiting” typical tourist places, is the new motivation for traveling. In parallel, another growing trend is the second home ownership for leisure and leisure-related investment purposes and the rise of a transnational class able to be “at home” and to live “like a local” in different contexts around the world [

41].

Digital platforms and their ability to offer (share) private accommodation, beyond traditional commercial and impersonal accommodations, and a wide range of services by locals, have the great potential to fulfill the demand of the new profile of the “explorer tourist”, leading to a touristification or everyday life, andl consequently, to a tourism gentrification that displaces not only people, but also commercial activities. Whereas mass tourism used to invade in guided tours some central areas of Valencia years ago, now the “explorer tourist” rents a bike or a motorbike to stroll about. The problem of Airbnb and Uber is that they are exacerbating an on-going problem, especially in central neighborhoods. They target the most attractive tourist-oriented areas of the city, in the case of Valencia, Ciutat Vella or Russafa. This latter case already had a very deep commercial gentrification process before the arrival of Airbnb [

44]. The new wave of gentrification led by Airbnb is reinforcing this gentrification process. With more than 450 apartments (1200 beds approximately) in a neighborhood of 23,000 inhabitants, the possibility of intensification is real. Today, Russafa has an occupancy rate of 40% in [

27], but a monthly revenue of 832 euros per apartment on average. A similar situation presents the historic district of Ciutat Vella, only 34% occupancy rate but 738 euros of monthly revenue. The potential for growth and occupation of tourist apartment is considerable, but the risk to transform these already gentrified districts, into what Lees called a “super-gentrification” or second-wave gentrification process is real [

45]. Another important consequence already visible is a complete shift of the geography of conflicts, now marked by a new centralization of protests in the city center, whereas in previous years were especially intensive in the peripheries, due to the proliferation of urban and tourist-oriented megaprojects.

The new geography of conflicts is reframing completely the landscape of social movements in the city. Social networks are not only promoting digital platforms but also social resistances. New urban-based movements, such as Entrebarris (between neighborhoods), Russafa descansa (Russafa rests), or Escoltem Velluters (listen to Velluters neighborhood), are some examples of grass-roots movements recently organized to face tourism negative impacts of digital platforms such as Airbnb. Political parties, traditional urban-based movements such as neighborhood associations and above all the local administration are in a situation of paralysis by analysis. The current local administration of Valencia is a constellation of left-wing political parties and grass-roots movements that were fueled by the protest cycle ended in 2011 with the economic and political crisis of those days. As explained above, the challenges they included in their political agenda, namely fight unemployment, privatization of public services, housing evictions or public participation methods, are still important but have been completely overtaken by the digital platform paradigm, which is precisely affecting housing, employment, and public services. Even more, touristified Spanish cities such as Barcelona are just beginning to design new policies to face platforms such as Airbnb, the same case as Valencia. Today, touristification and gentrification-led processes by digital platforms is an issue more discussed in legal, rather than in political arenas. A new political agenda for digital platforms, civil and labor rights is urgently needed in cities like Valencia, but as well in the amount of worldwide tourist urban destinations in which Uber, Airbnb or Deliveroo are starting to change housing, labor and mobility conditions. This political agenda should start distinguishing clearly for-profit “business-as-usual” digital platforms from other forms of sharing economies really desirable to improve social cohesion and environmentally friendly. Then, it would be useful to go beyond the legal conflict in which the majority of conflicts is embedded (taxi drivers claiming for Uber prohibition, Deliveroo rides claiming for labor rights, and neighbors defending a total prohibition of Airbnb apartments) to enter the political arena. It is in this arena in which a public policy for social housing, labor rights and inclusive mobility must be designed to face this new wave of neo-liberalization after the financial crisis, which digital platforms represent.

5. Conclusions

Digital platforms are the protagonist of a new chapter in the long history of capitalism and digital technology. Sharing economies appeared to be radical novelties as a response to the 2008 crisis. Airbnb, Uber, Deliveroo or Task Rabbit were born as a real possibility of sharing and were defended by some authors as a real environmentally friendly, socially fair and economic viable alternative to the conventional world of corporations. They were even announced as the new revolution of the commons. Nevertheless, capitalism, when a crisis hits, tends to be restructured with new technologies, new organizational forms, new forms of exploitation and new markets [

19] for the sake of capitalist accumulation. Digital platforms represent the new paradigm after the crisis. The “uberization” of the economy and the arrival of digital platforms seem to have more of simple continuity, than of an alternative or anti-capitalist social or economic paradigm, showing how capitalism is an incredibly flexible system.

This contribution has focused on a very definite aspect of the emergence of digital platforms: their complex and contested link with urban tourism. The main features of this for-profit sharing economy are visible in urban tourism: access through an app over ownership, “collaborators” instead of employees and the commodification of everything: from housing to the lifestyle of a city. Rather than a city with spatially and temporally limited tourist spots, the city landscape is itself a commodity. The development of digital platforms in cities such as Valencia, a consolidated tourist hotspot, as it has been shown, is simply spectacular in terms of rise of Uber or Airbnb users, and of course, in potential revenues. Traditional economic lobbies such as hotel chains, rent-a-car companies or real estate or transportation companies have invisible new competitors, with no face, head office or infrastructure in the city: the digital platforms. They are moving from the confrontation to the imitation of these new market models, for example, rent-a-car companies with app transportation services very similar to Uber, or international investment funds looking for apartments to boost the tourist apartment market available through the Internet.

Nevertheless, these new features have reinforced old social problems narrowly linked to capitalism contradictions, such as gentrification, touristification of urban centers, labor exploitation, and environmental impacts. Neighbors in central areas of cities such as Valencia are beginning a new wave of protests, in this case not against the administration or local construction lobbies and some ambitious urban mega-projects to attract tourism and investments, but to face California-based digital platforms and global investors that are in a more subtle way contributing to the touristification, gentrification and the commodification of urban areas. Meanwhile, local administrations, political parties and trade unions (especially defending taxi drivers) offer more reactive, violent or even NIMBY attitudes toward digital platforms than proactive alternatives. A combination of a brand new and necessary legal framework for digital platforms would be desirable, with a new comprehensive tourism strategy for the city, with land-use clear regulations, sustainable mobility measures, and a better distribution of the tourist offer to allow living in the center or in tourist areas.