1. Introduction

Since the middle of the 1980s, Spain’s economic policy backed property construction as the main instrument for generating wealth and economic growth. This enabled its productive system to consolidate and allow property investment to become the main source for the creation of surpluses for economic agents and savings for the population [

1]. Since the end of the nineties, bank credits boosted this circuit, facilitating financing for the purchase of homes for a large part of the population. For this purpose, the mechanism used was the securitization of loans on secondary markets, as in most developed countries [

2], which led to a spectacular increase in the prices of the homes and to a high level of private indebtedness.

When the global crisis began in 2008, with the consequential collapse of the credit markets and the increase in asset interest rates, property demand fell speedily, triggering difficulties for many property transactions underway for the sale of property and causing residential investments to fall sharply. This new scenario struck a hard blow to the stability of many companies and caused a fast increase in unemployment rates, which, in turn, reduced internal consumption. In this context, difficulties for the payment of mortgages and rentals by companies and individuals became widespread, with legal processes for dispossession and loss of use of properties increasing through both judicial and extrajudicial means.

The severity of the situation is explained by the crisis, but also by the fact that no public policy was put in place to alleviate the social impacts of this situation, with measures aimed at transferring rentals or the flexibilization of payment terms and conditions [

3]. On the other hand, public policies since 2011 focused its actions to reactivate the economy on an increase in export competitiveness, through labor devaluation and the re-floating of the banks that accumulated non-performing or toxic assets, in other words mortgage loans that the borrowers had stopped paying. In this regard, the first measures financed through the Orderly Bank Restructuring Fund had already been adopted by 2010 and, two years later, this policy continued with the nationalization of Bankia and Catalunya Bank and with the creation of the Bank Restructuring Assets Management Company (Spanish acronym: SAREB).

The difficulties involved in selling toxic assets in a housing market with devalued prices meant that, since 2013, a policy was implemented to attract foreign purchasers, with the approval of the law entitled “Act for the support of entrepreneurs and their internationalization” (Law 14 dated 27 September 2013). With this Act, international investment companies obtained tax breaks and bureaucratic barriers were simplified so that they could purchase property in Spain. In the case of private individuals not resident in Spain, they were offered the possibility of obtaining a visa and a residence permit for house purchases for amounts in excess of €500,000. As a consequence of all of the above, some private individuals and, above all, investment funds (the so-called vulture funds) began to acquire part of the assets held by the SAREB and the rest of the financial institutions at highly advantageous prices, through such instruments as Property Investment Companies (FII or SII), Servicers and REITs (in Spain, SOCIMIs) [

4].

Part of the homes acquired by the international investment funds and non-resident individuals have since been sold off at higher prices as and when the market has begun to be revalued, but the vast majority of these properties have been put to a secondary use or to rental, as there is growing international demand to acquire or lease these properties, at the same time as holiday homes is becoming a consolidating sector. All this has meant that the prices, which started at low levels as a result of the crisis, have begun to increase in coastal areas and in the central areas of large cities, especially since 2015. This price growth has transferred to the rest of the traditional rental market located in these areas, thanks to the approval of Law 4/2013 on measures for the flexibilization and encouragement of the home rental market, which enabled owners to increase the rental received or use their properties as holiday homes in a much simpler way. In consequence, we have seen over the last few years what is beginning to be considered a bubble in the rental prices of certain areas offering demand and centrality conditions in this new market.

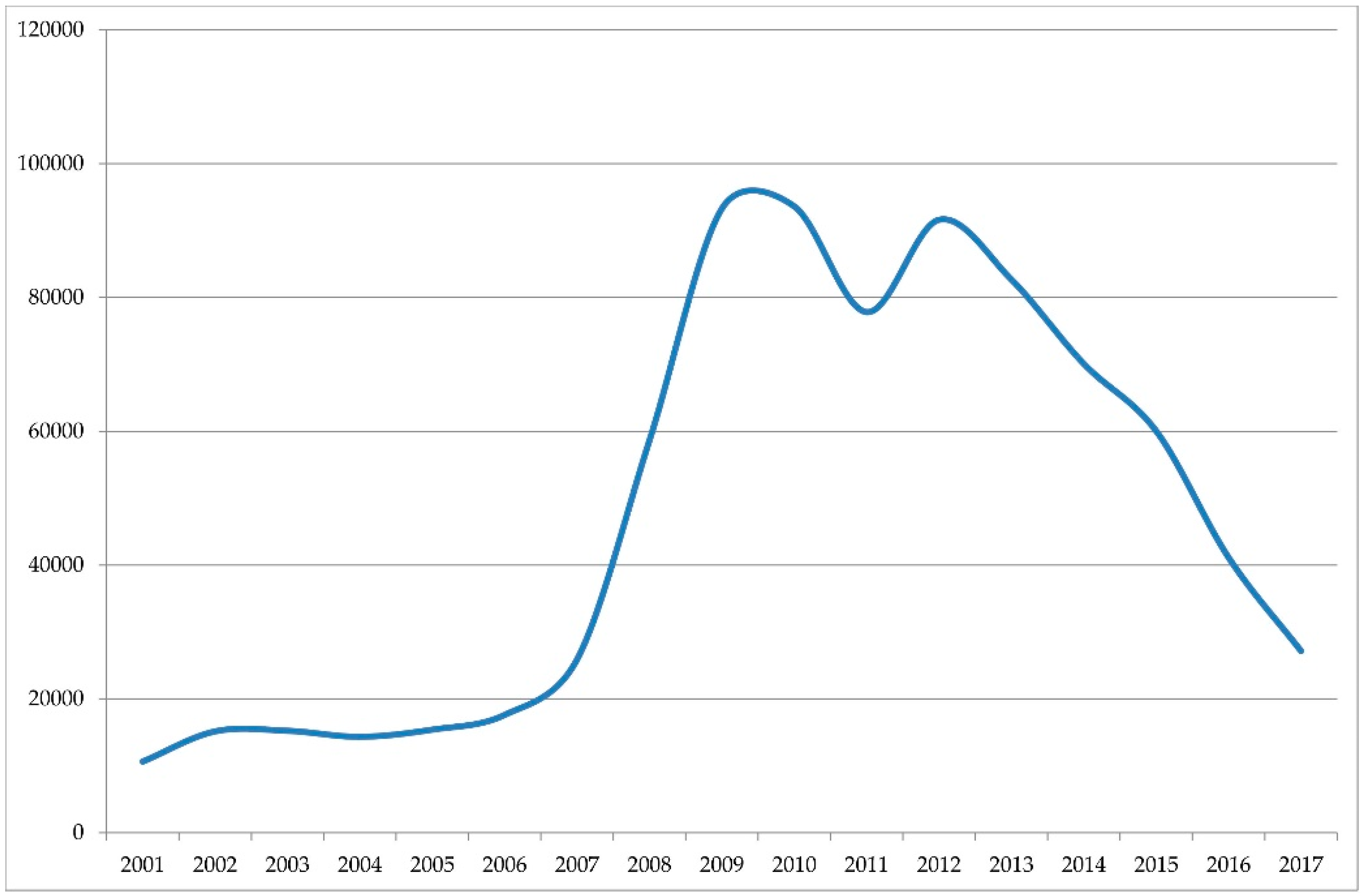

In this context concisely summarized above, dispossessions and losses of use are elements of great economic and social relevance. Official statistics enable us to know quite accurately the magnitude of the mortgage foreclosures carried out in Spain thanks to the publication of aggregated data by the General Council of the Judiciary. As can be seen in

Figure 1, mortgage foreclosures begun and entered on the Property Registries increased exponentially between 2008 and 2010, growing from total figures of less than 20,000 foreclosures begun in the first year mentioned to values close to 100,000 in the second. The number of new annual entries recorded stabilizes around this value, with a slight upturn in 2012 with the start of the second phase of the crisis in Spain or the debt crisis. Since then, and especially since 2015, registry entries have been gradually declining, but the number of foreclosures noted still in 2017 was higher than that recorded before the start of the economic crisis.

In the case of evictions due to non-payment of rental, data are scanter. The series published by the Spanish Statistical Office (INE) do not go back beyond 2005. In the period from 2009–2016, in urban leases of main homes due to non-payment of rental or deposits, the trend in the judicial rulings with a positive pronouncement (whether total or partial) in favour of the plaintiff reflects a peak in 2010, the highest figure in the series, before then beginning a marked decline until 2014. The information about recent years begins to reflect an upturn in the number of judgements for Spain as a whole (

Figure 2).

The most important thing here is to reveal to what extent this sequence of events reflects the fact that the loss of a home is a cyclical or circumstantial element or a structural element of Spain’s new economic model. In order to approach this response, we believe it is necessary to understand the phenomenon from the perspective of its incidence on an infra-municipal scale, a dimension that may indicate, from a geographical perspective, who are affected by these dispossession and loss of use processes. For this purpose, the goal of this article focuses on exploring the territorial impact and trend of mortgage foreclosures and evictions in the urban space of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria from 2009 to 2017. We are starting from the premise that this phenomenon is tightly linked to the economic crisis and to the political measures adopted, as highlighted in the pre-existing literature, but we believe that the analysis of this case will allow us to demonstrate that the end of the crisis has not meant that the loss of homes has a lower incidence for certain social groups. The way in which the crisis has been handled and the characteristics of the post-crisis period have benefited some population segments more than others, and this can also be seen in the right to accommodation.

The study of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria is of interest because it implies focusing the analysis on an island space that is highly attractive for international property demand. The city, one of the two capitals in the Canary Island region, had a registered population of 377,650 inhabitants in 2017, making it the most populous city in the Islands. Located in a European ultra-peripheral region, its economy is clearly specialized in services, many of them related to tourism, and port activities. It was particularly impacted by the economic crisis, to the extent that the unemployment rate rose from 15.8% in 2007 to 31.2% in 2013 according to the estimates of the Active Population Survey (EPA), therefore the lack of solvency of part of the population led to non-payment of housing-related debt due to the economic recession. The recovery that seems to be taking place since 2015 has not allowed the levels of employment to come close to those that existed prior to the crisis, nor has the capacity for expense on housing increased among the population at the same pace as rentals. The difficulties to satisfy the legitimate right to housing are, nowadays, a reality for a large part of the city’s population, which has suffered a process of impoverishment over the last decade.

2. Current Status of the Issue

The social impact since 2008 seen in the accelerated increase in mortgage foreclosures and evictions has led to the emergence of considerable studies from disciplines such as Geography, Economics or Sociology. Some schools of thought interpreting this phenomenon explain it from the perspective of the evolution of the capitalist system. Against this background, Critical Urban Theory considers late capitalism or post-Fordist capitalism to have its bases in the “New Urban Enclosures” and conceives the loss of housing as one of its clearest expressions, as a consequence of the reduction in the guarantees in accessing social reproduction mechanisms [

5,

6,

7,

8].

In a similar logic, another interpretative approach relates the development of the secondary accumulation system with dispossession [

9,

10], which is considered in and of itself as a tool inherent to the economic system to facilitate the accumulation of earnings for certain social groups and economic agents [

11].

Other complementary works focus, however, on the dynamic of the mechanisms in the late capitalist productive system as a factor explaining dispossession. Economic financialization (or the conversion of land and housing into financial assets) and the securitization of credits are considered to have been the main tools that have facilitated dispossession [

12,

13,

14], insofar as they imply continuous revaluation and this, in turn, implies the expulsion of residents.

In this line, in American literature on foreclosures, these link with the flexibilization of mortgage markets or high risk (subprime) mortgages [

15,

16]. This approach has meant that several studies have related the geography of evictions to other socio-spatial variables [

17], since some social groups were the ones who benefited from flexibilization in the terms and conditions for granting mortgage loans. In the specific case of island geographic contexts with a strong implantation of tourism, as is the case of the Balearic Islands, the touristification of the urban space has been conceived as a specific factor for the dispossession of homes [

18].

The preceding lines of argument are not mutually exclusive, therefore our analysis of the dispossession process in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria is carried out from an integrating perspective.

Geographical research into dispossession in Spain does not come from a long tradition. The first studies made use of foreclosure data, provided by the General Council of the Judiciary, from the 431 judicial districts existing in Spain [

19,

20,

21,

22]. These data make it possible to observe the process in the whole of Spain but on a judicial district scale, meaning that they do not distinguish houses from other types of real estate assets nor do they allow researchers to analyze evictions or to conduct urban studies. Similar studies were performed in subsequent years for Spain as a whole [

23] or in particular for the Canary Islands [

24].

Complementary to this, other studies have been carried out based on the disaggregated analysis of judicial records of foreclosures and evictions from specific judicial districts. This is the case of the studies conducted on the judicial districts of Palma in Majorca [

18,

25], Maó in Menorca [

26] and Las Palmas de Gran Canaria [

27]. The advantage of such a micro-scale approach is that it makes urban geographical analysis easier, given that the address is provided for each of the properties affected by dispossession or eviction and a larger number of variables can be obtained for analysis.

A different line of research draws on the systematic examination of housing advertisements of real estate agencies that are linked to banks. It is estimated that around 30% of these properties derive from dispossession processes (not necessarily judicial ones). This fact has given rise to a series of geographical studies on the cities of Lleida [

28], Tarragona, Terrassa and Salt [

29,

30,

31], Alicante, Murcia and Zaragoza [

32]; Madrid [

33] as well as the total of housing properties owned by SAREB in all Spanish municipalities [

34]. With a similar approach, some insights offered from other fields are also worth mentioning, as is the case of Raya [

35], whose research focuses on the autonomous communities of Madrid and Valencia. The drawback of these papers is that they do not allow the reader to identify the year of each foreclosure; they do, however, provide information on the characteristics of the property and on the bank that owns it.

Finally, the studies of Gutiérrez and Vives-Miró [

36,

37] make use of the registry of empty houses in the hands of financial entities created by the Catalonian Regional Government in 2016. The aim of this initiative was the creation of a special tax to be applied on these assets. This source makes it possible to find out the total number of houses accumulated by banks through foreclosures in Catalonia, providing information on the census area each property is located in and the entity that owns it.

The work we have carried out, and which we defend in this article, follows the path of those already mentioned who use judicial sources to analyze the geographical dimension of dispossession and loss of use. Nonetheless, it contains certain peculiarities that are commented on in the section on materials and methods and that enable us to reach relevant results.

3. Materials and Methods

The source of the information on which this study is based is the register of actions carried out by the Common Service of Notifications and Liens of the Judicial District for Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, comprising the municipalities of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Santa Brígida and Vega de San Mateo.

Spanish judicial districts of a larger size in demographic terms have what are known as Common Services, a court service unit that was set up based on Fundamental Law 19 dated 23 December 2003, and was subsequently developed by Regulation 2/2010. This Regulation specifies that Common Services perform the notification and enforcement acts with which they are charged by the Courts, such as evictions, liens and removal of deposit holders. Since they are also charged with registration and distribution functions, at the same time, they have to use an application that enables them to process documents electronically.

In the case of the Canary Islands, there are only two Common Services of Notifications and Liens, namely those for the judicial districts of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and Santa Cruz de Tenerife. They both use the same type of register, within the framework of the computerized procedural management system used by the Administration of Justice in the Canary Islands, known as Atlante, similar to that in place in other autonomous regions.

The information from these registers is generally published by the High Courts of Justice in the various regions and by the General Council of the Judiciary. The original extensive information is only available for the members of the courts themselves or the Common Services. In our case, we were granted authorization to consult it.

The fields contained in the register for each of the notes include the note number, the party involved, type of action, courts ordering the action, address, legal proceedings, date of registration, date of action, and current status. This information refers to both homes and other premises.

In the case of the different types of actions taken, the ones we considered were evictions and memoranda for taking possession. Eviction is the legal act whereby the lessee or owner of the property is removed, at the same time as, in the latter case, the owner loses his or her property rights in favour of the new acquirer by order of the judicial authority. Memoranda for taking possession are actions whereby an owner loses the ownership of a property in favour of a new acquirer by judicial order, without the need for eviction. Liens, as they do not entail the loss of ownership in and of themselves nor any eviction, were not taken into account.

The consultation of the register of the Common Service of Notifications and Liens for the judicial district of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria has enabled us to create a database adapted to our purposes, which only considers those records with a positive status, that is to say those in which the processes for eviction or taking of possession were culminated. Prior to processing, we eliminated 94 records since we detected situations of duplication. The information was homogenized and the postal addresses confirmed. The cartographic representation of the losses of ownership and use were elaborated using the postal addresses and generating kernel density maps.

The kernel density analysis calculates the territorial density of a phenomenon (point or linear) in a raster pattern using parameters of distance and neighborhood by a quadratic function. The calculation must take in account the bandwidth or distance, the size of the pixel and the possible existence of attributes for each entity. The result for each pixel is the sum of the values obtained with the different calculations for each raster unit. In our analysis, we used this method as a simplified cartographic modelling tool, generating maps with exit cells of 10 m and calculation radii of 200 m (bandwidth).

4. Results

Between 2009 and 2017, a total of 4138 case files aimed at the forcible deprivation of use and ownership were executed in the judicial district for Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, i.e., an average of 460 case files per year. Taking the mean registered population in the period as a reference, we obtained a proportion of a little over one case file (1.2) per thousand inhabitants. This figure does not apparently seem very high, however we must remember that deprivation of use and dispossession by judicial order must be considered as the tip of the iceberg of this phenomenon, since the parties involved generally agree to early sales, voluntary abandonment of the property or out-of-court settlements in order to resolve the conflict in a less costly way, and, in all cases, to avoid a judicialized solution to the problem.

In our study of the actions taken in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, we have been interested in exploring the procedures involved, the types of action used, the nature of the parties involved and the intra-urban location of the properties affected. We will discuss the study of these variables from a time-based analysis, as this will enable us to provide useful comments in order to understand better the reality of deprivation of use and dispossession. We shall offer our results on the basis of these criteria, but first we will present the evolution over time of dispossession and loss of use processes as a whole.

4.1. Evolution over Time

As reflected in

Figure 3, the crisis in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria gave rise to an increase in judicial actions related to dispossession and evictions, as shown by the fact that the number of positive actions in 2009 (239) rose to 620 in 2011. The growth curve in these three years can be explained by two fundamental reasons: The first is that judicial proceedings, particularly in dispossession actions, take place over a long period of time. Judicial intervention is not immediate, and the procedural protocols established have to be followed, thus delaying the expression of the crisis in the actions analyzed until about two years after the start of legal proceedings. The second reason is that, with the start of the crisis, the Spanish government adopted palliative measures attempted to maintain a higher level of solvency among the population, despite the increase in unemployment. The so-called “Plan E” which tried to inject liquidity through an ambitious and costly infrastructure plan controlled by local governments is a paradigmatic example. The measures remained in force until the end of 2010 in some cases, which delayed non-payments.

From 2011 and until 2013, the figures remain very high but with a slight downward trend. These are years in which the loss of homes takes on great media significance. This stage corresponds with the second phase of the economic crisis in Spain, which has become known as the “debt crisis,” in which the high level of public indebtedness generated in the preceding years provoked a change in the State’s economic policy, leading to the start of wage devaluations, budgetary austerity, and deficit control in the context of the adjustment measures adopted by the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Starting from 2013, the figures for legal proceedings tend to stabilize at above 400, with this figure improving slightly in 2017, which might be seen as a delayed symptom of the mild economic recovery begun in Spain in 2015. Nonetheless, just as a clear relationship can be appreciated between the number of judicial proceedings and the crisis, the figures did not demonstrate with the same forcefulness as might be expected the association between the number of legal actions taken and the economic recovery.

4.2. Judicial Procedures

From the perspective of the procedures applied, for the purposes of an overview, we have grouped together, on the one hand, those representing dispossession, in the majority foreclosures of title, and, on the other hand, those that only represent deprivation of use. The most abundant actions between 2009 and 2017 were those implying loss of ownership (59.9% of positive enforcement actions). Those intended for deprivation of use represented, therefore, 40.1%. The most frequent among the first group were enforcement of judicial title and mortgage foreclosures, which only represent 25% of all case files. We also found other grounds for dispossession that gave rise to different civil, criminal, insolvency and arbitration proceedings. Therefore, loss of ownership cannot only be interpreted as the result of the impossibility to pay a mortgage loan, but also as the consequence of general economic insolvency. We must also not forget that dispossession is sometimes related to family break-ups, conflicts in the acceptances of inheritances, criminal actions, etc.

Deprivation of use is instrumented in most cases through oral trials and, fundamentally, by appealing to article 250.1.1 of the Civil Procedure Act (Law 1 dated 7 January 2000), as amended by Law 19 dated 23 November 2009, on measures for encouraging and speeding up the process for rental and energy efficiency of buildings. Article 2.8 of this Act specifies that oral hearings must be used for those cases “dealing with claims for amounts relating to non-payment of rental and sums owed and, similarly, those based on the non-payment of rental or sums owed by the lessee, or on the expiry of the term established contractually or by statute, and intended for the recovery of the possession of property by the owner, usufructuary or any other person entitled to own a rural or urban property granted under a lease, whether ordinary or financial, or under a crop sharing agreement.”

Nonetheless, in addition to this more generalized widespread situation, namely the use of oral hearings for non-payment of rental, we also find proceedings for unregistered assignments (250.1.2); summary protection for the possession of real estate (250.1.4); claims by holders of in rem rights (250.1.7) and for petty amounts (250.2). These claims for unregistered occupation, summary protection for possession or to re-establish in rem rights are usually aimed at recovering properties that have been occupied without any prior contractual relationship. In fact, most of these occupancies arise after a contract, therefore many of these situations are judged through article 250.1.1 [

38].

We are of the opinion that it is of great interest to show the time sequence of the positive proceedings for loss of property and of use in different ways in order to understand better the phenomenon under study. As can be observed in

Figure 4, the case files for deprivation of use and ownership grow in parallel and intensely in the early years of the crisis (2009–2011). However, after 2011, there is a distinct behaviour over time between the different types of proceedings. The evictions (deprivation of use) maintain stable data in the next three years before showing, after 2014, with an alleged “post-crisis” situation, a constant increase in their number to the point where there are more positive proceedings for loss of use in the last two years than for loss of ownership. On the other hand, dispossession proceedings show a descending curve from 2011 until 2013, before stabilizing and once more recording a major decline in the last two years, between 2016 and 2017. During this last period, the number of properties affected is lower than that recorded in 2009.

With respect to the loss of ownership, it can be inferred that this differential evolution is related to the early stage of the inability to pay caused for many households and companies by the economic crisis. In the second stage, after 2011, the smaller number of actions correlates with the gradual reduction in private indebtedness, due above all to the greater difficulty in accessing third-party finance for the purchase of property, due to the hardening of the mortgage conditions imposed by credit institutions. Therefore, the evolution in dispossessions reflects the peculiar sequence of the economic crisis and the policies applied as a consequence of the same in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

On the other hand, the evolution in the deprivation of use proceedings is an indicator of the vulnerability of the population with regard to accommodation in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, during both the crisis and post-crisis periods. In this sense, it must be understood that, since 2011, a series of interrelated events have taken place that explain the situation and also explain why the economic improvement in recent years has not been reflected in a reduction in the number of evictions. In this sense, we can cite such factors as: (a) The increase in demand for rental properties, as a result of the toughening of the conditions for accessing bank loans for home purchases and the insecurity of potential buyers following their experience during the years of the crisis; (b) the employment market has become more and more precarious with the successive wage devaluations and the worsening of employment conditions, within the framework of the strategy to increase competitiveness through the devaluation of the labor factor; (c) non-resident individuals and foreign investment funds have begun to control a growing part of the market for rental properties, facilitated by the liberalization measures intended to clean up the banks’ toxic assets; (d) holiday homes have grown spectacularly in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria without any effective regulation having been sanctioned in the Canary Islands; and (e) as a result of the approval of Law 4/2013 on Measures for the flexibilization and encouragement of the home rental market, lessors now have conditions enabling them to increase rents or terminate contracts on advantageous conditions. In short, this indicates the persistence of economic weakness in a segment of the population even at times of supposed recovery, and expresses the way in which an attempt has been made to overcome the crisis by means of the exclusion of a large part of the population through the lack of compensating public policies.

4.3. Judicial Proceedings

From the standpoint of the type of legal practice applied, it must be remembered that the enforcement of title is not synonymous with eviction proceedings. This can also be extrapolated to oral hearing proceedings, albeit exceptionally (a little less than 2% in our case). If we analyze the practices applied and group them into the categories of memoranda for taking possession and evictions, it can be seen that the number of evictions predominated over the recovery of possession in a proportion of three out of every four actions and, in the specific case of enforcement proceedings (enforcement of title, mortgage foreclosure, etc.), 62.8% implied evictions. In other words, abandonment, free handover or making the property available to the claimant has occurred in a smaller number of cases. The fact that eviction is the most common judicial action adopted is an indicator of the severity and drama of the situation that people have been living through in the last decade in the city of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

The evolution over time of evictions and recovery of possession follows approximately the same sequence as mentioned above with respect to the actions as a whole (

Figure 5), with the only difference that evictions have been increasing since 2013 (not the case of memoranda for taking possession), and this is due, to a large extent, to the increase in evictions for non-payment in recent years. It is therefore paradoxical that, in the economic recovery stage, the number of evictions is coming closer and closer to the figures shown in the hardest years of the crisis.

4.4. Nature of the Parties Affected

The registers for the actions carried out in the judicial district for Las Palmas de Gran Canaria has enabled us to identify whether the party affected by dispossession or eviction proceedings is a company or a private individual. As can be seen in

Figure 3, most of the actions affect natural persons. If we take into account the impact over the period analyzed, it is possible to observe in this sequence that the case files for companies peak between 2011 and 2014, in other words during the debt crisis period. The figures subsequently decline gradually, showing a clear trend in the economic recovery and a lower degree of vulnerability in the post-crisis period. However, among natural persons, always more affected, the trend for legal action to diminish with the economic recovery is less clear.

This disparity in the impact and in the time sequence of the data available informs us of a single phenomenon, the loss of ownership and use of property, but two different scenarios, each one with distinct causes. In the first case, the one that occurred during the crisis period, the economic difficulties brought about by the recession drove both legal and natural persons into situations of eviction. In the second scenario, it is the way in which the country has emerged from the crisis that justifies the divergences in the impact on companies and on private individuals.

4.5. Urban Location of the Proceedings

The territorial distribution of the legal actions adopted are generally concentrated in the city’s central spaces, those included within the surroundings of the port area and Las Canteras beach (La Isleta, Puerto, Santa Catalina and Guanarteme neighborhoods) to the north of the city and the quarters of Triana, Arenales and Lugo, close to the foundational core of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. These two areas constitute urban centers as they concentrate the largest part of the city’s private service activities, public administrative functions, regulated tourism offerings and holiday homes, as well as being the sectors with the best connectivity to the rest of the urban space. Nonetheless, as can be seen in

Figure 6, the incidence of dispossession and rental-related evictions overflowed these spaces and also affected intensely the urban periphery.

However, we can appreciate an inverse territorial tendency in the distribution of dispossessions and evictions. In the first case, the presence in the city’s central spaces and the sprawl in the urban periphery is higher until 2013. On the contrary, the evictions have a greater territorial presence in recent years in the periphery and, especially in the urban centre, linked to the acquisition of holiday homes.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In summary, dispossession in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria was concentrated in the early years of the crisis, whereas loss of use has affected the more recent period, the incipient post-crisis. For this reason, while the problem, in the first few years, affected more those who could not pay the loans with which they had bought their homes, it has now spread more generally to those groups unable to pay their rent due to unemployment, the impossibility to obtain a stable or fairly-paid job, or due to the increase in rental prices. Similarly, we have seen that the situations underlying dispossession or eviction processes are more diverse than might have been expected, as they are not always associated with mortgage foreclosures or non-payment of rent. Furthermore, these circumstances affected both companies and individuals during the crisis, as it was a widespread situation of insolvency and there was no policy implemented to compensate either side. The post-crisis, however, is having a particular impact on certain households with a lower level of income, so the situation is now more selective.

The sequence of these processes correlates with their territorial impact. With the crisis, legal actions affect a large part of the city, with numerous interventions in areas of its most recent expansion, where the mortgage foreclosures for non-payment occur, whereas, in the last few years, the judicial proceedings are focused on certain central areas, those recording the largest number of evictions, a phenomenon paralleling the revaluation of property rentals.

As a consequence, the maximum intensity of the dispossession processes recorded during the crisis years, and the dramatic situations that accompanied it, must not make us forget that there is still a persistent social vulnerability, albeit with a new face, namely evictions, as a reflection of the inability of a wide sector of the population to resolve their housing problem. It could be said that, in the face of a “hard” situation, namely the loss of a home and the instalments paid under the mortgage contracts signed with the banks, the vulnerability in the post-crisis period has emerged in “soft” situations, related to the difficulty in accessing a rented home with all of the new formats of job flexibilization and precarious contracts.

The results obtained in the time-trend study of mortgage foreclosures and evictions in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria are consistent with the aggregate figures known for Spain as a whole, although they present some nuances that enable us to understand that the loss of a home is not as homogeneous a phenomenon as the forcefulness of the figures seems to indicate. In other words, the phenomenon is much more heterogeneous and multi-faceted, despite which it could be interpreted as a circumstantial and also structural consequence of the capitalist system.

Specifically, the dispossession enforcements resolved present a similar trend as in the series of enforcement actions begun for the country as a whole, except for the time delay caused by the judicial proceedings. In Spain overall, the case files opened reflect two periods of growth: 2008–2010 and 2012. In the judicial district for Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, there is only one period of decline recorded, namely from 2010 to 2011. In the case under study, therefore, the first stage of the crisis had a greater impact than the subsequent debt crisis. The reason is not so much an improvement in the economic situation in the Canary Islands compared to other regions of Spain during the second stage of the crisis, but rather a lower level of private indebtedness in the Islands.

The analysis over time of evictions due to non-payment of rent has fewer benchmark studies, as the urban analyses usually group together the data for multiple years, either focusing on short periods or else contrasting figures from specific years [

18,

20,

25]. While the figures from the National Statistics Institute at national level, as already mentioned, recorded accelerated growth until 2011, followed by a stop-start decline in recent years, the initial growth in the judicial district for Las Palmas de Gran Canaria lasted somewhat longer, until 2012, when the figures stabilize until 2015 before recording growth since then, attaining absolute values even higher than those in the years of the first crisis. This difference in how the series evolves, leaving aside the distortions that might arise from the fact of not comparing completely identical variables, is due to the contrasting of distinct socio-economic structures, that of Spain and that of the Islands, that were affected to a different extent and pace by the crisis and the adjustment measures. This speaks once more, as in the case of dispossessions, to the heterogeneity of the process.

In the case of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, the recovery policies based on rental market flexibilization, the deregulation of holiday homes and the internationalization of the housing market have given rise to the expected results, making transactions more dynamic and triggering the revaluation of the properties, associated with the loss of use of habitual homes. The harmful effects of the new focus of the rental market are particularly serious if we take into account the unfavourable situation of the city in such aspects as per capita income, the unemployment rate, precarious labor contracts or the proportion of the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion [

39].

As a consequence, this differentiation of the case analyzed with respect to the State as a whole can also be extrapolated to those affected. During the crisis, dispossession processes had a major impact on both legal and natural persons. In the recent years of the recovery, however, it is the private individuals, i.e., householders, who have been most harmed compared to companies, who seem to have adapted more successfully to the new economic scenario. In a daring interpretation, we might say that everyone, businesses and households alike, were doubly impacted by the situation of the property market insofar as their assets were devalued and they suffered losses of both ownership and use, at the same time as they have had to remediate the financial institutions by backing, through the State, the loan granted for the purpose by the European Central Bank.

Lastly, the study of the housing loss in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria has provided elements for reflecting on the circumstantial or structural nature of the process. A strictly circumstantial vision would be based on a scenario characterized by an increase in legal proceeding for dispossession and eviction at times of crisis and a contrary behavior during economic booms. With this logic, if the period of prosperity generated an excessive valuation of properties and greater indebtedness, then the recession should be manifested through a more acute process of housing loss, which is in line with the logic of those explanations based on market operation. As we have seen in our study, however, this is not what has happened, so the purely circumstantial explanation is not completely satisfactory.

From a structural perspective, the excessive financialization of the property market, through the granting of high-risk mortgages, and the securitization of these financial assets are the structural elements explaining the increase in dispossessions since 2008, although it was the start of the crisis that highlighted this situation, as has been indicated in the pertinent literature. In this line, financialization and securitization are once more the structural factors of late capitalism that explain the situation arising in the years of economic recovery, except that, in this case, it is through the internationalization and flexibilization of rental markets.

The persistence of these structural elements defines different stages in secondary accumulation over the last two decades. An initial growth stage through property possession (from the end of the 1990s until 2008); a second growth stage through dispossession (the crisis, from 2009 until at least 2013), already stated by Harvey [

6]; and a final growth stage through repossession, in recent years, as was expressed by Janoschka [

40]. These global structural trends must be nuanced in the light of the peculiar features of each territory, but they seem to explain, in a more precise way, the importance of dispossessions in the past and, in recent years, of evictions due to non-payment of rent. This latter situation negates the fact that, after the crisis had passed, the difficulties for satisfying the accommodation problems for extensive collectives within the population had also been overcome. In fact, these difficulties remain because they form part of the structure of the current housing market.