Abstract

The home-sharing platform, Airbnb, is disrupting the social and spatial dynamics of cities. While there is a growing body of literature examining the effects of Airbnb on housing supply in first-world, urban environments, impacts on dwellings and dwelling typologies remain underexplored. This research paper investigates the implications of “on-demand domesticity” in Australia’s second largest city, Melbourne, where the uptake of Airbnb has been enthusiastic, rapid, and unregulated. In contrast to Airbnb’s opportunistic use of existing housing stock in other global cities, the rise of short-term holiday rentals and the construction of new homes in Melbourne has been more symbiotic, perpetuating, and even driving housing models—with some confronting results. This paper highlights the challenges and opportunities that Airbnb presents for the domestic landscape of Melbourne, exposing loopholes and grey areas in the planning and building codes which have enabled peculiar domestic mutations to spring up in the city’s suburbs, catering exclusively to the sharing economy. Through an analysis of publically available spatial data, including GIS, architectural drawings, planning documents, and building and planning codes, this paper explores the spatial and ethical implications of this urban phenomenon. Ultimately arguing that the sharing economy may benefit from a spatial response if it presents a spatial problem, this paper proposes that strategic planning could assist in recalibrating and subverting the effects of global disruption in favor of local interests. Such a framework could limit the pernicious effects of Airbnb, while stimulating activity in areas in need of rejuvenation, representing a more nuanced, context-specific approach to policy and governance.

1. Introduction

In its short lifespan, home-sharing platform Airbnb has revolutionized tourism by developing a framework that enables a global pool of applicants to rent homes on-demand, in shorter increments of time, and at a premium [1]. In turn, this phenomenon is transforming the way we use, access, and design domestic space, and is disrupting the social dynamics of cities around the world. While there is an emerging body of literature examining Airbnb and its impacts on housing markets in first-world, urban environments, its effects are contingent on local particularities, including social, political, economic, and morphological systems, and they are therefore difficult to generalize. Moreover, Airbnb’s impact on dwellings and dwelling typologies—as distinct from property—remain underexplored. As such, this paper investigates “on-demand domesticity” through a case study analysis of Melbourne, Australia. There, the uptake of Airbnb has coincided with the high-density apartment boom to produce some significant social transformations, but also unique formal reverberations, as evidenced by a number of domestic mutations emerging in the city’s suburbs. Through an analysis of available spatial data, this paper discusses the intersection of the three categories of Airbnb listings—entire home, private room, and shared room—with the domestic landscape of Melbourne, highlighting the need for development and planning strategies to address this new kind of quasi-commercial, quasi-residential use and the array of challenges it has already wrought. Ultimately, this paper argues that if Airbnb presents a spatial problem, it might benefit from a spatial solution. Rather than defaulting to generic caps or blanket bans on listings as implemented by other global cities, this research proposes that strategic planning could be deployed as a means to recalibrate and subvert global disruption in favor of local interests.

The sharing economy has exploded in the last decade in the context of increasing resource limitations, postindustrial economies, neoliberal austerity and privatization, and property speculation and accumulation [2]. Less production and fewer resources have forced consumption to be reconceptualized to enable a high turnover of existing products, and property is no exception. Airbnb is an example par excellence of what is known in business terms as ‘collaborative consumption’ [3]: a model designed to maximize value from latent assets (in this case, housing) through short-term leasing, or “sharing” [1]. While still arguably in its infancy, the origins of the sharing economy can be traced back to the arrival of Web 2.0 at the turn of the 21st century, when the social web [4] began to facilitate new global communication and “virtual communities” and promised increasing horizontality through “user-generated content” [4]. The first wave of sharing made possible by the internet was largely content and image-based, exemplified by not-for-profit organizations like Wikipedia (2001) and Creative Commons (2001) and later, free but sponsored social media sites like Facebook (2004). Importantly, as Belk points out, these platforms operated outside of “expectations of reciprocity” [5] or payment for service. By 2007, the smartphone had delivered personal GPS, opening up new possibilities for the real-time sharing of resources and services. In the wake of the global financial crisis’s conditions and politics of austerity [6], there was much need and enthusiasm for the peer-to-peer sharing of goods and services via platform cooperatives [7]. But the global debut of home-sharing platform, Airbnb, in 2008 and its ride-sharing counterpart, Uber, in 2009, marked the beginning of a new kind of peer-to-peer model that is inherently transactional—one in which everything is able to be commodified [8], including domestic space.

In Australia, the uptake of Airbnb has been rapid, enthusiastic, and largely unregulated [1]. Endorsed by both the public and private sectors—with government organizations like Tourism Victoria [9] and corporate giant Qantas [10] forging recent partnerships with the platform—it is now responsible for contributing over $400 million each year to the Victorian state economy alone [1,11]. Significantly, Airbnb’s arrival in Australia in 2012 coincided with the beginning of a strategic market-led apartment building program in the eastern states, designed to accommodate the growing population and avert a recession following the decline of mining investment [12]. Unlike other parts of the world which have struggled to regain their footing following the 2008 collapse, Australia has experienced a continuous period of economic prosperity, largely as a result of this population growth and high-density housing boom [13], which has seen the rapid transformation of east coast cities, including Melbourne, Sydney, and to a lesser extent, Brisbane. While apartment building has stimulated growth in the construction industry as intended [14], increasing supply has done little to alleviate the housing affordability crisis [13] which until now has continued to escalate in Melbourne and Sydney. In Australia, America, and the UK, rising property prices have been fueled by global investment in ‘stable’ assets. Tax offsets like capital gains tax exemptions and negative gearing have incentivized development but have also pitted owner-occupiers against investors, inflating house prices and driving up rents [13], which in Melbourne reached record highs in 2017 [15]. Airbnb and other home-sharing platforms have been blamed for exacerbating the crisis, with investors buying up apartments to lease exclusively as short-term rentals for a higher return.

Melbourne is a particularly pertinent city for interrogating the architectural and urban effects of Airbnb, not simply because of its already pressured housing market, but because of its laissez-faire approach to business and property development, which has enabled both Airbnb usage, and until recently, the design quality of apartments, to carry on unregulated. While Sydney has recently implemented caps on the number of days Airbnb properties can be listed and enabled bi-laws to be passed by strata owners corporations [16], Airbnb activity in Melbourne remains unrestricted. The popularity of short-term holiday rentals in Sydney has posed challenges in terms of rental affordability, housing supply, and nuisance activity. However, because the design quality of apartments has been regulated since 2002 in New South Wales [17], the overall standard of residential construction is higher than in Victoria, and so the effects of disruption on the built fabric of the city are less overt. By comparison, while multi-residential development in Victoria is also subject to planning permissions from the local or state authority, until recently there were no planning guidelines to protect the internal amenity of individual apartments, such as minimum room sizes. Victoria’s “Better Apartment Design Standards” [18] were only introduced in 2017 after years of poor quality development and mounting pressure from the architecture profession whose input is still not mandatory in the design of multi-residential development. This gap in the planning process has resulted in a glut of homogenous dwellings in the inner city which lack basic amenities such as natural light to bedrooms, cross-ventilation, and private outdoor space [19]. Considered unlivable by many residents, these kinds of apartments have found a new market on Airbnb, and are often let year-round as holiday rentals [1].

In contrast to Airbnb’s opportunistic use of existing housing stock in other global cities, in Melbourne, there is some evidence to suggest that the relationship between short-term rentals and the construction of new homes has been more symbiotic—perpetuating, and in some cases, even driving housing models. As such, this research paper asks the following: what tangible effects is Airbnb having on the built fabric of Melbourne, and how might we establish a policy framework to effectively address the challenges and opportunities that this disruption presents for the city?

2. Materials and Methods

Primary geospatial data sourced from InsideAirbnb.com provides a useful starting point for understanding how Airbnb is disrupting the spatial dynamics of metropolitan Melbourne. This data has been modelled according to listing type (entire home, private room, and shared room), relative to urban infrastructure, and in consideration of existing housing typologies in the urban, inner, and middle rings where Airbnb activity exists. Building on a discussion of issues explored in a short opinion piece for Architecture Australia [1], this paper interrogates anomalies and hotspots within this dataset by isolating and reviewing Airbnb listings of interest. By examining spatial data in combination with interior and exterior photography included in the listings, it has been possible to identify and locate specific sites of interest as case studies for further analysis. Publically available architectural marketing and planning drawings have been sourced, and case studies have been visited to develop a clear picture of the spatial context. One such case study—the supersized house, which perhaps best demonstrates the reverberations of Airbnb on domestic form—has been analyzed in detail in order to understand the regulatory processes which enabled its development. Planning submission drawings have been closely scrutinized in relation to the National Construction Code (NCC) and local planning schemes to determine existing grey areas and loopholes that have facilitated the construction of new shared practices and typologies. Finally, a context-specific, strategic planning approach to regulation to constrain and target disruption in a way that is useful for the city has been tested through an action-based, speculative design-research project.

3. Results

When modelled, data suggests that Airbnb is taking available housing stock off the market where it is in high demand: in the city center close to employment and public transport [1]. This trend is consistent with many other global cities such as London [20], Amsterdam [21], and New York [22] that have since taken steps to cap the number of days Entire Homes can be listed, or in the case of Berlin, ban them all together [23].

Due to the current lack of regulation in Melbourne, Entire Homes, which exist in large concentrations in the inner city (Supplementary Material 1), can be let exclusively as holiday rentals, and are often listed by professional hosts with multiple properties. Entire Homes constitute the majority of Airbnb rentals in Melbourne—around 57% (Table 1)—which on average have very low occupancy rates [1]. As we have seen in parts of central London and elsewhere, large swathes of vacant property, either as a result of the ebbs and flows of tourism or as untenanted investments, have implications for housing affordability and supply, but can also pose broader urban challenges for local businesses, street life, and security, particularly at certain times of year [1,24].

Table 1.

Percentage Breakdown of Airbnb listings in Metropolitan Melbourne by listing category. Data sourced from InsideAirbnb.com, 2016.

The distribution of both Entire Homes and Shared Rooms in Melbourne closely corresponds with the intensity of new apartments in the central business district (CBD) and the inner city. Shared Rooms only constitute about 2% of all listings (Table 1), but they present a variety of other social and regulatory challenges [1]. These listings tend to be concentrated in a small number of isolated new developments in the western end of the CBD close to existing backpacker’s accommodation and in the northeastern corner of the CBD near RMIT University—an area which has traditionally catered to large populations of international students (Supplementary Material 2). Developments such as these, which pre-date the implementation of minimum design standards, are characterized by ‘buried’ bedrooms and inadequate floor, storage, and outdoor space. The Shared Room listings operating within them are often overcrowded, with two-bedroom apartments accommodating up to eight guests [1] and being marketed as longer-term housing options for international students, contract workers, and new migrants. When they are used this way—effectively functioning as informal hostels—these properties do not comply with the health and hygiene regulations required for this building classification [25]. Moreover, with four to a room, these apartments significantly exceed the assumed occupational load upon which fire engineering assessments for residential towers are based (two people for the first bedroom and one for every other bedroom) [25]. Given the prevalence of Shared Room listings within particular developments, this kind of en-masse overloading could have grave consequences for fire safety and emergency egress—issues which have been brought to the fore following recent fires at the Lacrosse Building in Melbourne and Grenfell Tower in London [1].

More promising is the distribution of Private Rooms in Melbourne, which represent around 41% of listings (Supplementary Material 3; Table 1) [1]. While Private Rooms are still prevalent in the inner-city, their pattern is more diffuse in the inner and middle suburbs, which is in line with Australia’s predilection for very large houses but shrinking households [1]. Private Rooms in Melbourne commonly take the form of a spare room or bungalow in a family home or share-house occupied by other residents. They are more likely to be peer-to-peer, promoting efficient use of latent space and minimizing periods of vacancy. With strategic planning, this kind of Airbnb usage in Melbourne might yield very positive outcomes, increasing the number of people within the housing stock and dispersing the economic benefits of the tourist economy [1].

However, without regulations, even the Private Room model is susceptible to exploitation, as demonstrated by one particular supersized house identified in the inner suburbs of Melbourne, which has seemingly mobilized the home as a machine for maximizing profit (Figure 1a). This 18-bedroom, 18-bathroom, post-nuclear house leases its rooms year-round on Airbnb for approximately AUD$70.00 per night. At maximum occupancy, the house is capable of generating around AUD$8800 p/w in rent, or around 14 times the average income for a rental property in the area.

Figure 1.

(a) Supersized 18 bedroom, 18 bathroom Airbnb house in an inner suburb of Melbourne, Australia. Drawing by Jacqui Alexander. (b) Existing conditions plans and elevation drawings as documented in the original planning submission, with a total of nine bedrooms. Drawing by Jacqui Alexander.

Typologically, this uncanny domestic model sits somewhere between a suburban detached house and a hotel. Private Rooms are accessed via long corridors, with a large communal kitchen accommodating four industrial-sized fridges and not one but two island benches, a communal laundry, gymnasium, living room, and lounge. The reconceptualization of the private space of the home as a shared, commercial space is evident in the interior photographs, which are complete with exit signs, fire extinguishers, security cameras in common areas, and tactile indicators, suggesting that the house was subject to public-use regulations. Further investigation confirms that the home is not new, but a significantly remodeled older property, likely constructed in the 1970s. In 2009, a development application to partially demolish, expand, and remodel the home was approved, but prohibited the use of the land as a “backpackers’ lodge, hostel, nurses’ home, residential aged care facility, residential college or residential hotel without further consent of the responsible authority” [26]. The permit conditions have been obtained but it has not been possible to locate the endorsed plans. A subsequent planning application lodged two years later reveals that the existing house at the time of submission had a total of nine bedrooms (Figure 1b), and permission was being sought to double the yield to 18 bedrooms. Additional research reveals the house is now listed on the Public Register of Rooming Houses in Victoria [27], establishing its current classification under the building code.

In Victoria, a rooming house is simply defined as: “a building where one or more rooms are available to rent, and four or more people in total can occupy those rooms” [27] However, these buildings have a long history as affordable accommodation for people who do not meet the minimum income threshold or do not have the required rental history to enter the mainstream market. They are commonly operated by church groups, private housing providers, or registered individuals. According to Consumer Affairs Victoria, a rooming house resident is someone whose “room in a rooming house is their only or main residence” [27] and who does not need to sign a tenancy agreement to live there. While the supersized house is primarily marketed to tourists via Airbnb who would not typically meet the definition of a ‘rooming house resident’, it appears to occupy a grey area by incentivizing stays of six months or more with discounted rates, while also accommodating short-term stays.

4. Discussion

The supersized house can be read as an urban artefact—an extreme example of the way in which the sharing economy can shape cities in the absence of adequate regulatory and planning controls. It raises some interesting questions in relation to housing provision, legislation, equity, and affordability. Airbnb is clearly filling a gap in Melbourne’s housing market for short- and medium-term tenancies, as demonstrated with both Private and Shared Room listings. Is this example merely elevating the caliber of rooming houses that currently exists and charging accordingly? Or is it disingenuous to register and advertise oneself as a rooming house if the intended market is primarily tourists? According to the Tenants Union of Victoria’s (TUV) 2016 report, the median weekly rental cost for rooming houses in Melbourne is $195.00 (approximately $28 per day) [28] or roughly half the rate of the supersized house. Taking into consideration their respective target markets and price points, there is little grounds to compare these two models in practice. The question remains: what happens when candidates seeking actual rooming house accommodation contact this provider? While Airbnb has effectively made homes available for public use, access remains at the discretion of the host, and as such, risk is managed in other ways, including prohibitive fees, rating systems that can engender bias, or outright exclusion [29].

Moreover, will this house set a precedent for more supersized share-houses, and what effect will that have on rents? This particular case study is located in an inner suburb with a long history of affordable, informal student share-housing. It is prudent to note that when this domestic case study was identified in 2016, the host was operating a total of 81 Airbnb listings in Melbourne, many of which were Private Rooms in similarly overblown, newly-built residential constructions, in or around the same neighborhood. Further research is required to understand the planning processes and building classifications which enabled these other developments.

Does the planning process and building code need to change to allow for new shared typologies that can be more appropriately regulated according to their use? Whether or not the supersized house is ethical or equitable, it is certainly opportunistic and highlights the current inadequacy of both the National Construction Code (NCC) and the statuary planning processes in addressing the bourgeoning shared practices and typologies that Airbnb and other home-sharing disruptors have wrought. But while it can be argued that the provision of poor-quality apartments in Melbourne has been perpetuated by their popularity as short-term rental accommodation, there is also evidence to suggest that in the Australian context, Airbnb’s Private Room model might play a useful role in intensifying the suburbs, promoting more efficient use of space in existing large homes and dispersing the economic benefits of the tourist economy [1].

If we agree that Airbnb presents a spatial problem, it might benefit from a spatial response. Rather than default to blanket bans and caps, this research advocates that through design and strategic planning, we can recalibrate the patterns of disruption through the following strategies: limiting its capacity for inequity and stimulating local economies where productive (Figure 2a). In the context of Melbourne, this would mean restricting Entire Home usage in the inner city, where competition for housing is high, and incentivizing Private Room letting in middle suburbs in need of rejuvenation, intensification, and greater housing diversity. Currently, a significant obstacle in promoting peer-to-peer home sharing in Melbourne’s middle suburbs is the radial train and limited tram network, making it difficult to move around, especially with the added encumbrance of luggage [1]. However, the Melbourne Metro Tunnel currently under construction and the proposed Airport Rail Link—both earmarked for completion by 2026—present an opportunity to revolutionize tourism in Melbourne in a way that could benefit visitors and citizens (Figure 2b). The Airport link which is planned to operate between Tullamarine and Albion Station could unlock the western suburbs, attracting tourists on inbound services to the city and decentralizing tourism [1]. Through strategic planning, Private Room rental could be promoted in the suburbs to optimize spare bedrooms in large homes, intensifying distributed neighborhoods and stimulating local business (Figure 2c).

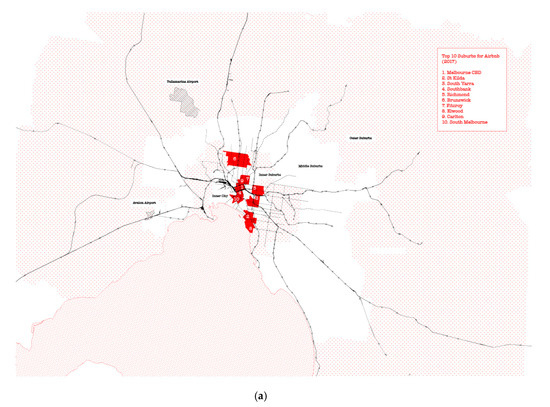

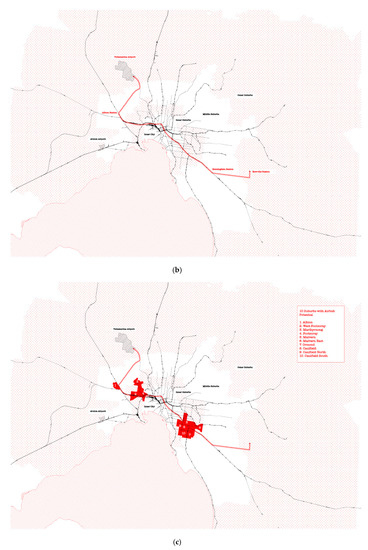

Figure 2.

(a) The top ten most popular suburbs in Melbourne for Airbnb rentals (2017). Nine of the ten are considered “inner urban”; the other, Brunswick, is “inner suburban”. These suburbs are all well-serviced by train and public transport networks. The current inefficient radial rail network is a primary obstacle in decentralizing Airbnb use in the city and dispersing its economic benefits. (b) The government’s current plan to develop an airport rail link by 2026 could revolutionize tourism in Melbourne, connecting Melbourne’s east and west through a new continuous route and making the western suburbs accessible for tourists on inbound services to the city. (c) Ten suburbs with Airbnb potential have been identified, which will become more accessible to tourists via two new major transport infrastructure upgrades: the airport rail link and the Melbourne Metro Tunnel. Western suburbs such as West Footscray are earmarked for rejuvenation in the Maribyrnong structure plan and could benefit from home-sharing intensification. On the other hand, established southeastern suburbs like Ormond, which has very large houses but shrinking households, could optimize space through private-room rental.

As well as maximizing efficiencies in existing properties, Private Room letting could help drive housing innovation in these suburbs by encouraging small-scale, grassroots infill development that could cater to temporary guests but also the growing numbers of empty-nester and single parent households, as well as families with dependents [30]. Currently in Victoria, infill types like granny flats must only house dependents and must be removed when the family member moves out or moves on. By following New South Wales’ lead in making granny flats a permanent and more broadly accessible housing option, the state government could strategically incentivize the development of additional autonomous accommodation on single allotments to support home-sharing in the broadest sense. Local controls in combination with Airbnb’s property review mechanism could lift the design quality of new dwellings, and the increased densities could help the council to fund infrastructure and amenity improvements for residents.

While the findings in this paper are highly particular to the social, economic, political, and urban context in Melbourne, this research seeks to demonstrate that a strategic, “glocal” approach to Airbnb regulation—one which considers the interplay of global and local forces—could be leveraged to achieve positive urban outcomes for citizens. Can we establish rules of engagement for Airbnb activity in Melbourne to catalyze better and more diverse housing provision? For Melbournians, infill development may come as a welcome alternative to densification via the current controversial high-rise, high-density model [31], delivering infrastructure that would endure long after the tourists have left the scene [1].

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2413-8851/2/3/88/s1.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Monash University for support in the development of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alexander, J. Disruptive Domesticity: Housing Futures and the Sharing Economy. Arch. Aust. 2018, 107, 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Self, J.; Bose, S.; Williams, F. Home Economics; The Spaces: London, UK, 2016; pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Botsman, R.; Rodgers, R. What’s Mine is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, T. Open Source Paradigm Shift. O’Reilly Media, June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R. Sharing Versus Pseudosharing in Web 2.0. Anthropologist 2014, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkis, F. Austerity Urbanism and the Makeshift City. City 2013, 17, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, T. Uberworked and Underpaid: How Workers are Disrupting the Digital Economy; Polity: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thom, J. Belong Anywhere, Commodify Everywhere: A Critical Look into the State of Private Short-Term Rentals in Stockholm Sweden. Master’s Thesis, KTH, Stockholm, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mannix, L. While Uber is Illegal, Airbnb gets Government Help. The Age. 6 December 2015. Available online: http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/while-uber-is-illegal-airbnb-gets-government-help-20151206-glgm6j.html (accessed on 14 January 2016).

- Qantas: Feel at Home Earning Qantas Points with Airbnb. Available online: https://www.qantaspoints.com/earn-points/airbnb (accessed on 9 September 2018).

- Galloway, A.; White, A. Airbnb Melbourne: $400million a year Injected into Victorian Economy. Herald Sun. 2017. Available online: https://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/victoria/airbnb-melbourne-400m-a-year-injected-into-victorian-economy/news-story/c97afe034dae2344f8f204876eb03284 (accessed on 2 August 2017).

- Australian Property Observer. Australia’s Housing Boom Finished, But So Is the Drag from Mining: HSBC’S Paul Bloxham. Available online: https://www.propertyobserver.com.au/forward-planning/advice-and-hot-topics/78116-the-housing-boom-is-over-but-so-is-the-mining-drag-hsbc-s-paul-bloxham.html (accessed on 9 September 2018).

- Daley, J.; Coates, B.; Wiltshire, T. Housing Affordability: Re-Imagining the Australian Dream; Grattan Institute, University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Construction Industry Observer. Two Up and Two Down—Trends forecast the Australian Construction Market Report. May 2018. Available online: https://www.acif.com.au/forecasts/summary (accessed on 9 September 2018).

- Kirsten, R.; Zhou, C. Melbourne Renting: Rent at Record Highs and Rising Faster than Income and Vacant. Domain. 2018. Available online: https://www.domain.com.au/news/melbourne-renting-rent-at-record-highs-rising-faster-than-incomes-and-vacant-20170209-gu7wpm/ (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Available online: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-06-05/airbnb-changes-as-nsw-government-reaches-compromise/9836648 (accessed on 9 September 2018).

- New South Wales Planning & Environment Department. State Environmental Planning Policy No. 65—Design Quality of Residential Flat Development (SEPP 65) Sydney. 2002. Available online: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/inforce/08f04365-88c2-4fe5-b56a-f76fdd390b10/2002-530.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Victorian Office of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. Better Apartments, Design Standards. Available online: https://www.planning.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/9582/Better-Apartments-Design-Standards.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Alexander, J. Airbnb Urbanism. Future West J. Aust. Urban. 2016, 1, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Airbnb: Responsible Hosting in the United Kingdom. Available online: https://www.airbnb.com.au/help/article/1379/responsible-hosting-in-the-united-kingdom (accessed on 9 September 2018).

- Lomas, N. Amsterdam to Airbnb-Style Tourist Rentals to 30 Nights a Year per Host. Tech Crunch. 10 January 2018. Available online: https://techcrunch.com/2018/01/10/amsterdam-to-halve-airbnb-style-tourist-rentals-to-30-nights-a-year-per-host/ (accessed on 9 September 2018).

- Editorial: New York Deflates Airbnb. The Economist. 27 October 2016. Available online: https://www.economist.com/news/business/21709353-new-rules-may-temper-airbnb-new-york-its-future-still-looks-bright-new-york-deflates (accessed on 9 September 2018).

- Payton, M. Berlin Stops Airbnb Renting Apartments to Tourists to Protect Affordable Housing. The Independent. May 2016. Available online: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/airbnb-rentals-berlin-germany-tourist-ban-fines-restricting-to-protect-affordable-housing-a7008891.html (accessed on 9 September 2018).

- Catherine, C. Speculative Vacancies 08: The Empty Properties Ignored by Statistics, Prosper Australia; Prosper Australia Research Institute (PARI): Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Building Codes Board. National Construction Code Series 2017; Volume 2: Building Code of Australia Class 1 to Class 10 Buildings; Australian Government and State and Territories of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2013; pp. 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Moreland City Council. Planning Permit No. MPS/2008/523; Moreland City Council: Coburg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Victorian State Government Department of Consumer Affairs. Public Register of Rooming Houses. Available online: https://www.consumer.vic.gov.au/housing/renting/types-of-rental-agreements/sharing-in-a-rooming-house/public-register-of-rooming-houses (accessed on 28 February 2018).

- Lina Caneva. Rooming House Tenants pay High Price for Living in Poverty. Available online: https://probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2016/10/rooming-house-tenants-pay-high-price-living-poverty/ (accessed on 28 February 2018).

- Edelman, B.; Luca, M.; Svirsky, D. Racial Discrimination in the Sharing Economy: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Am. Econ. J. 2017, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, A. Housing Diversity: Adapting 1.0 Infrastructure for 3.0 Lives. Arch. Aust. 2018, 107, 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Worrall, A. Respected Melbourne Planning Expert Michael Buxton Retires from RMIT. Domain. 13 May 2018. Available online: https://www.domain.com.au/news/respected-melbourne-planning-expert-michael-buxton-retires-from-rmit-20180512-h0zwq1/ (accessed on 9 September 2018).

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).