1. Introduction

In 1982, California mandated accessory dwelling units (ADUs) as suitable housing for seniors, college students, and low-income households [

1]. ADUs (also known as granny flats, in-law, or accessory apartments) are small rental units that are studios or one- or two-bedroom units. ADUs can be attached to the lot’s primary housing unit (usually a single-family residence), detached in the rear yard, or located above a garage. Indeed, ADUs are appropriate for seniors because ADUs can facilitate aging in place when the unit is located on the senior’s or family member’s lot [

2]. ADUs may also be appropriate for college students who desire short-term accommodations with limited budgets and possessions [

3]. For low-income households, however, two factors undermine the suitability of ADUs as low-income housing. The first is a lack of agency oversight. The second is the efficacy of ADUs produced as regulated low-income housing units.

Regarding agency oversight, many cities responded to California’s ADU mandate by modifying their zoning codes to tenure ADUs as rentals and to require ADU homeowners to record covenants attesting to the homeowner’s occupancy in the ADU or the primary housing unit. However, these covenants did not obligate an homeowner to rent their ADU to any household. In addition, very few cities imposed covenants on ADUs (e.g., maximum rent, occupant income limits, and/or effective period) that would regulate the units as available low-income housing. In their survey of the ADU zoning in 87 Los Angeles County cities, for example, Mukhija, Cuff, and Serrano reported that the cities of Duarte, Santa Fe Springs, and Sierra Madre required low-income occupancy as a condition of the ADU approval [

4]. While those authors did not verify low-income occupancy or low-income ADU production, this study has determined that the low-income conditions have been removed from these cities’ zoning codes and any ADUs that were available as low-income housing no longer exist.

Regarding efficacy, California aspires to address the housing needs for households in all economic segments by requiring each city to accommodate their fair-share of a region’s low-income housing needs [

5]. To achieve this housing equity, California’s Housing Element Law sends each city a multi-year housing allocation that identifies the city’s low-income and market-rate housing needs [

6]. In order to increase ADU production statewide, California allowed cities to count

potential ADUs towards low-income housing needs in 2003. To be clear, potential ADUs are an estimate that is based on a planner’s zoning analysis as opposed to produced units. While California has recently begun to collect longitudinal data regarding low-income housing production [

7], it is not clear whether significant quantities of regulated ADUs as low-income housing exist or are available. Furthermore, no study has established any relationship between potential ADUs and ADU production. For example, from 2007–2014 California allocated 390 low-income and 282 market-rate housing needs to the City of Santa Cruz, CA, USA a city known for its progressive ADU planning [

8,

9]. During that time, homeowners produced 148 ADUs [

10]. In terms of efficacy, this ADU production was respectively 38% and 54% of the city’s allocated low-income and market-rate housing needs. These statistics indicate that ADUs did increase Santa Cruz’s overall housing inventory; however, for what households were these units available? At present, Santa Cruz contains 465 legally permitted ADUs, but only 8% (

or 39) require low-income occupancy. This low proportion suggests that homeowners produced ADUs largely as market-rate units.

The confluence of a lack of oversight and the unproven efficacy of ADUs as low-income housing means that California has low-income housing units that exist on paper, but not in operation. This is the heart of California’s Faustian Bargain. This compromise was necessary in order to appease cities that were resistant to increasing their low-income housing inventory. Without long-term covenants similar to those found on regulated low-income housing units (e.g., tax-credit, voucher subsidized, or publically owned), can ADUs serve as actual low-income housing? The answer is no. ADUs may increase local housing inventory and may be more affordable than other market-rate housing types due to the unit’s small size; however, ADUs may not be priced for or available to low-income households [

11,

12,

13]. This paper argues that for every count of potential ADUs towards low-income housing needs, a bona fide low-income unit that would have been situated in a regulated multifamily or voucher housing unit was lost. In this compromise, California and cities with exclusionary zoning win, while low-income households and cities with multifamily zoning lose.

The purpose of this research is to explore the implementation of California’s ADU mandate and has five research questions that explore the conditions that influence ADU production in California cities. First, are the housing allocations proportionally similar for cities classified as low-, moderate-, or high-income? Second, to what extent do cities count potential ADUs towards overall or low-income housing needs? Third, what was the efficacy of a city’s count of potential ADUs towards overall and low-income housing needs? Fourth, what conditions increase a city’s probability of counting potential ADUs towards overall or low-income housing needs? Lastly, what conditions influence a city’s ADU production?

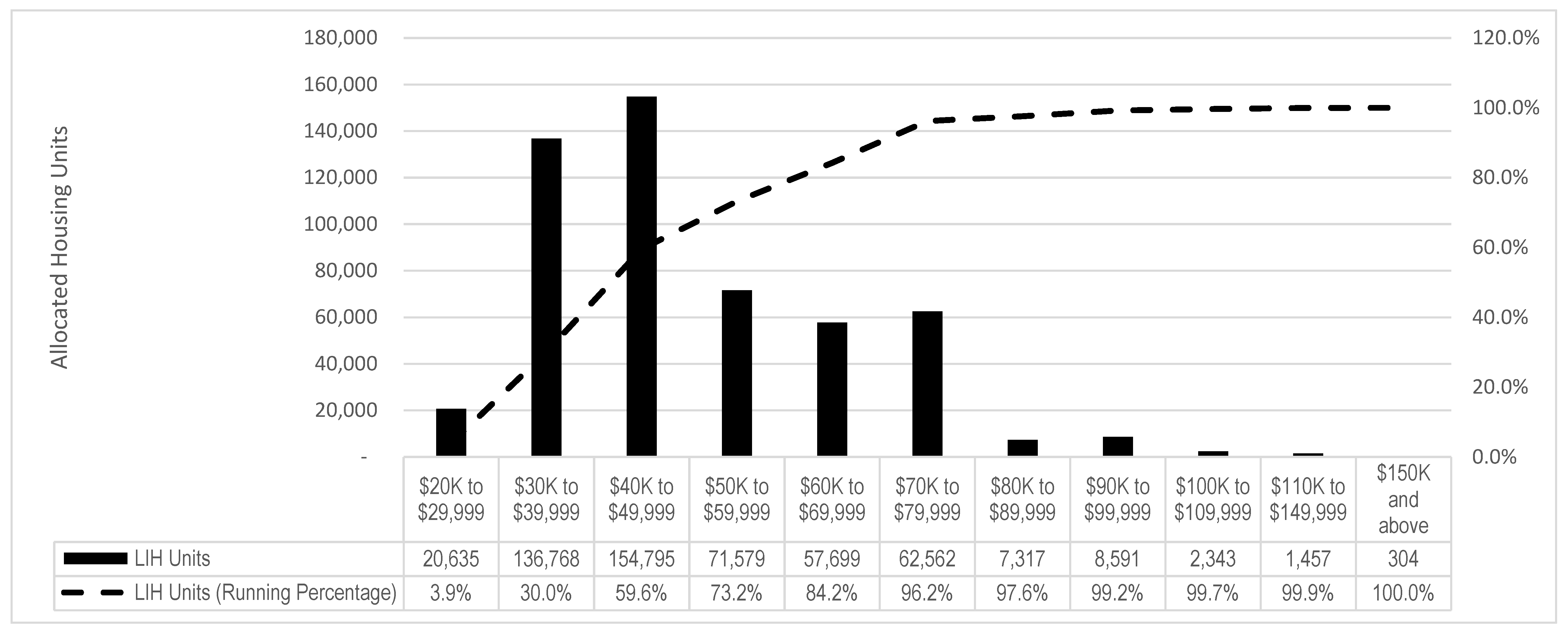

After examining a stratified random sample of 57 California cities from 2006 to 2014, this study found that the housing allocations advanced a proportional fair-share intent because 60% of allocated housing needs must accommodate low-income households. However, the allocations might also concentrate the poor in low-income cities because the sample’s low-income cities were required to quantitatively accommodate more than three times the quantity of low-income housing needs than the high-income cities (36,500 and 11,500; respectively). Regarding counting potential ADUs towards overall housing needs, 56% (or 32/57) of the sample counted potential ADUs to increase overall housing inventory. Regarding counting potential ADUs towards low-income housing needs, the analysis indicates that 76% (or 13/17) of the sample’s high-income cities counted potential ADUs as low-income housing, in contrast to 45% (or 9/20) of moderate-income cities and 25% (or 5/20) of low-income cities. Of these potential ADUs as low-income housing, none of these cities’ zoning codes imposed covenants that would regulate an ADU’s maximum rent, occupant income, or effective period. Regarding the efficacy of counting potential ADUs, planners counted 842 potential ADUs and 749 of those ADUs were designated as low-income housing. While the data indicates that 759 ADUs were produced for an overall efficacy of 90%, none of these units could be verified as available to low-income households.

Inferentially, the analysis indicates that if a city contains a college or has high household incomes then those conditions increases a city’s probability of counting potential ADUs toward overall or low-income housing needs. Regarding the conditions associated with ADU production, the analysis indicates that cities with colleges and high incomes were positively associated with ADU production. By contrast, a city’s density, proportion of renters, and compliance with state housing law were negatively associated with ADU production. However, when counts of potentials ADUs are included in the model, then the counts were associated with increased ADU production, Overall, this research found that ADUs did increase the housing inventory for this sample of cities; however, it is not clear if the potential ADUs that were counted towards low-income needs actually provided housing satisfaction for low-income households because (1) the zoning codes for these cities did not maintain any low-income covenants and (2) the housing plans for these cities did not verify whether these ADUs were low-income and available to low-income households.

Following this introduction, the literature review discusses the importance of zoning in the U.S. and the intersection of ADUs with senior, innovative, and shadow housing. The background explains how California’s primary housing intervention (e.g., the Housing Element Law) integrated ADUs into state housing law, the cities’ subsequent responses, and then recent housing law amendments that pertain to ADUs. Next, the paper details this study’s methods, data, and results. Lastly, the discussion unpacks the analysis and discusses whether ADUs can be considered low-income housing and makes suggestions regarding closing the loopholes that perpetuates California’s Faustian Bargain. In this study, California’s Second Unit Law and Housing Element Law operate as mandates because all cities must adhere to state housing policy. For clarity, this paper references the Second Unit Law as the ADU mandate. California makes no legal distinction between cities and incorporated towns [

14]; therefore, this paper references the sample as cities. Lastly, California classifies ADUs as accessory structures. Accessory structures take the form of garages, storage units, children’s club houses, artist studios, pool houses, and accessory dwelling units. This paper focuses on ADUs that are intended to satisfy housing needs.

4. Methods and Data

This study examines California’s ADU mandate to explore what conditions influence ADU production in California cities and has five research questions. First, are the fair-share housing allocations proportionally similar for cities classified as low-, moderate-, or high-income? Second, to what extent do cities count potential ADUs towards overall or low-income housing needs? Third, what was the efficacy of a city’s count of potential ADUs towards overall or low-income housing needs? Fourth, what conditions increase a city’s probability of counting potential ADUs towards overall or low-income housing needs? Lastly, what conditions influenced each city’s ADU production? The following discussion explains this study’s context, research design, units of analysis, sampling frame/sample, tests, and data.

Contextually, ADUs interface with the Second Unit Law and the Housing Element Law because both laws endeavor to increase housing supply by influencing local government behavior. The Second Unit Law positions ADUs as suitable housing for seniors, college students, and low-income households. The Housing Element Law’s requires cities to modify their internal density (via the fair-share housing needs allocations) and allows cities to count potential ADUs towards low-income or market-rate housing needs. Since more than 530 local governments must prepare housing plans that require a CAHCD assessment, CAHCD staggers each plan’s effective period by its home region: the Los Angeles region, 2006–2014; the Sacramento region, 2006–2013; the San Diego region, 2005–2010; and the San Francisco region, 2007–2014. In response to these overlapping effective periods, this research employs a longitudinal design, with a period of study (2007–2014) that observes the initial integration of ADUs into the required housing plans.

The units of analysis are cities, of which California has 494. Due to the required data and limited resources, this study employed five criteria from both laws to create a sampling frame of 255 cities and subsequent sample. First, the study examined low-income housing production in which CAHCD, COGs, and cities participate. In regions without a COG, CAHCD creates the housing allocation. Second, regions with urban central cities were examined as opposed to entirely rural regions. Suburbs in urban regions may resist multifamily zoning in order to reduce the potential relocation of urban low-income households and their social service needs [

145]. Third, cities that existed at the inauguration of CAHCD’s compliance reports in 1990 were examined. Prior to 1990, there is no reliable data. Fourth, twelve cities with populations greater than 200,000 were eliminated in order to focus on California’s small- and medium-sized cities. California classifies its cities as general law or charter. The former are subject to state law, while the latter enjoy broad autonomy regarding adherence to state planning laws [

146]. Eleven of the eliminated cities are charter cities (

Supplementary Table S2). In addition, 97% of California’s cities maintained populations of less than 200,000 in 2000. Lastly, each city must have its 2007–2014 and 2015–2023 housing plans. The former indicates counts of potential ADUs, while the latter indicates ADU production. The resulting sampling frame consisted of cities from the following urban regions: Los Angeles (

n = 140), Sacramento (

n = 14), San Diego (

n = 16), and San Francisco (

n = 85).

The stratified random sample consists of 57 cities that reflect low-, moderate-, and high-incomes as categorized by each city’s 2000 median household income (MHI). When the COGs devised the fair-share housing allocation for the 2007–2014 planning period, they examined year 2000 MHI (and other data) to quantify low-income and market-rate housing needs. After plotting the sampling frame’s standardized MHIs, clusters of cities appeared near −0.5, +0.25, and +1 values. A comparison of the standardized clusters from the population and sampling frame discerned complementary patterns (

Supplementary Figure S1). Based on these distributions and the influence of Pfeiffer’s research on city character and household incomes, the −0.5 to −0.26 bin was categorized as low-income cities (

n = 74), the +0.25 to +0.49 bin as moderate-income cities (

n = 22), and the +1.0 to +1.9 bin as high-income cities (

n = 17). The sample consists of 20 randomly selected cities from each of the low- and moderate-income categories and all 17 cities from the high-income category. The sample’s regional distribution is Los Angeles (24 out of 140 cities), Sacramento (4 out of 14 cities), San Diego (five out of 16 cities), and San Francisco (24 out of 85 cities).

Table 1 identifies the sample by group, income, and allocated housing needs (circa 2007–2014).

The first research question (

Are the fair-share housing allocations proportionally similar for cities classified as low-, moderate-, or high-income?) was answered with a descriptive analysis of each city’s 2007–2014 fair-share housing allocation, as determined by the COGs. This analysis also references the collective fair-share housing allocation for the urban regions. The second research question (

To what extent do cities count potential ADUs towards overall or low-income housing needs?) was answered with a descriptive analysis of each city’s 2007–2014 quantified objectives. As determined by each city’s planners, the quantified objectives indicate counts of potential ADUs by quantity and by income (e.g., low-income or market rate; [

6], § 65583(b)(2) and (c)(1)). This analysis created the variable

potential ADUs. The third research question (

What was the efficacy of a city’s count of potential ADUs towards overall or low-income housing needs?) was answered with a descriptive analysis of each city’s 2007–2014 quantified objectives and the evaluation of the 2007–2014 housing plan that was located in the 2015–2023 housing plan.

The fourth research question (What conditions increase a city’s probability of counting ADUs towards overall or low-income housing needs?) was answered with logistic regression. The response variable ADUs Y/N (0 or 1) measures whether the quantified objectives identified counts of potential ADUs. The response variable ADUs as LIH (0 or 1) measures whether quantified objectives identified potential ADUs as low-income housing. The fifth research question (What conditions influence a city’s ADU production?) was answered with negative binomial regression. The response variable ADU Production measures the quantity of ADUs constructed during 2007–2014, as per the 2015–2023 housing plans.

As count data,

ADU Production has no negative values and is not normally distributed. Due to these conditions, the study employed negative binomial regression (rather than quasi-Poisson and zero-inflated Poisson) because of its goodness of fit measures (i.e., AIC, log likelihood), exponential and standardized coefficients, and usage in other planning studies [

148,

149]. The results discussion also includes the predicted probability (i.e., logistic) or expected counts (i.e., negative binomial) of selected variables. In both cases, each subject variable’s probability, or expected counts, was calculated by using the subject variable’s values (i.e., if dichotomous: minimum, maximum; if continuous: the minimum, mean, maximum) and the means of the other predicting variables multiplied by the model’s coefficients. The regression tests did not indicate multicollinearity (variance-inflation statistics <3; [

150]).

Table 2 lists the research questions, methodology, data, and primary data sources.

Data

For all regression tests, development constraints was the experimental variable. College, compliance, density, income, renters, and senior citizens were control variables. Data sources were the cities, COGs, CAHCD, California’s Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office (CACCCO), the U.S. Bureau of Census (Census), and the Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences (IES). The COGs are as follows: Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), Sacramento Area Council of Governments (SACOG), San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG), and Southern California Council of Governments (SCAG).

Development constraints measured whether a city’s ADU development standards required excessive lot-size, enclosed parking, and/or a deed restriction, as noted by previous studies [

4,

43,

75,

78]. For example, Beverly Hills required excessive lot-size, Mill Valley required excessive lot-size and deed restrictions, and Pacifica required excessive lot-size, deed restrictions, and enclosed parking, whereas San Ramon did not require any of these standards. Due to model parsimony, these restrictions were transformed into an index reflecting the intensity of the identified ADU zoning restrictions (i.e., a score in the range of 0, 0.33, 0.66, and 1;

Table 1).

College measured the presence of any two- or four-year public/private college or university (CACCCO, IES) in the city because California allows cities to classify college students as low-income households. For-profit institutions were excluded because they primarily serve adult students who hold full-time positions and do not relocate.

Compliance measured how each city’s housing plan complied with the Housing Element Law (CAHCD) in the nine years prior (1998–2006) to the period of study (2007–2014). This measurement should indicate a city’s evidence of planning for current and future housing needs. After examining each city’s 1998–2006 annual compliance status, the data was averaged.

Density measured the density of housing units per square mile of a city’s land area (CENSUS). Cities with low

density should be more likely to accommodate potential ADUs due to the prevalence of single-family homes and/or land available from large parcels. In addition, California requires each city’s housing plan to identify sites with appropriate densities to accommodate current and future housing needs.

Income measured each city’s MHI and was transformed by dividing each value by 1000 to ease interpretation (CENSUS). Cities with higher incomes should be more likely to count ADUs overall and ADUs as low-income housing rather than approve multifamily housing that may contain low-income households. Due to parsimony, the study employs this single measure of income to increase the model’s linearity and explanatory power rather than dichotomous measures.

Renters measured each city’s proportion of occupied rental units in relationship to total occupied housing units (CENSUS) and

senior citizens measured each city’s proportion of persons older than 65 years in relation to a city’s population (CENSUS). California requires its cities to quantify and plan the housing needs of both

renters and

senior citizens. All Census data is year 2000, as these statistics were employed by planners when they created the examined 2007–2014 housing plans. In other models, the following variables were tested and excluded because they were collinear or non-significant:

distance (miles between the city hall of each examined city and its central city),

political will (general law or charter), and

poverty (proportion of households in poverty).

Table 3 provides a data summary, and the Supplementary lists all data references.

6. Discussion

This study examined a stratified random sample of California cities in order to determine what conditions influence ADU production and the analyses presented a series of results that require further discussion, but are limited to the sample. California transmits housing needs allocations to each city as an intervention to provide housing equity to all residents. The allocations regionally redistribute low-income housing needs and housing growth. The study determined that the sample’s fair-share housing needs allocations required high-income cities to proportionally accommodate more low-income housing needs than moderate- or low-income cities. By contrast, the housing allocations directed large quantities of low-income housing needs and housing growth towards lower-income cities.

Table 1 documents the substantial housing needs allocations for the low-income cities of Chula Vista, Hesperia, and Lake Elsinore in contrast to the lighter loads for the high-income cities of Los Gatos, Ross, Pleasanton, Tiburon, and Villa Park. As noted by Baer, California’s allocations may actually grandfather the low-density sins of the older built-out communities, while newer cities and cities with access to land must pay for those sins with higher densities [

156]. However, two points should be considered.

First, the sample cities responded to allocations from multiple COGs, with each COG employing a unique allocation methodology. Second, the sample contains only 57 cities, not each region’s population of cities. In response to these limits, this study also analyzed the fair-share housing needs allocations for the examined urban regions, both collectively and individually. In either case, the analysis of this regional data confirmed a proportional fair-share intent with 60% of housing needs apportioned to low-income households, but the allocations also directed high quantities of low-income housing needs and housing growth to lower-incomes cities. While the Los Angeles and San Francisco COGs have published reports that quantify housing permits issued in relation to their housing allocations, these reports do not detail the production of low-income housing units, the spatial distribution of allocated housing needs, or the distribution of allocated housing needs by a city’s median household income [

161,

162]. An examination of these additional measures would allow scholars and housing activists to evaluate the equity embedded in a fair-share housing needs allocation at the allocation’s onset.

This paper argued that allowing cities to count potential ADUs towards low-income housing needs was California’s Faustian Bargain because of the lack of agency oversight and the unproven efficacy of counting potential ADUs as low-income housing. This study determined that 32 cities (or 56%) counted potential ADUs to satisfy overall housing needs and 27 cities (or 47%) counted potential ADUs towards low-income housing needs. However, there was no evidence that these cities’ zoning standards could impose low-income covenants for ADUs. If a city’s zoning code is silent, then it is unlikely that the city can legally enforce such low-income conditions. The housing plans indicated that 759 ADUs were constructed during the period of study and these units represent a 90% (or 759/842) efficacy of counting potential ADUs towards overall housing needs. However, the plans did not provide any evidence that the constructed ADUs were priced-for or available-to low-income households. This deficiency represents a 0% efficacy for counting potential ADUs towards low-income housing needs. In addition, the analysis also compared the ADU efficacy to the sample’s housing production efficacy and found dissimilar patterns: 20% for low-income housing needs, 139% for market-rate housing needs, and 67% for overall housing needs. A few reasons can explain the differences in efficacy.

Regarding the sample’s 20% efficacy for low-income housing needs, in 2010 California terminated redevelopment tax-increment finance during a budgeting shortfall. When redevelopment agencies were active, these agencies must set-aside 20% of tax increment funds for low-income housing programs. Many housing plans listed low-income housing projects and programs that were terminated due to a lack of redevelopment funding (e.g., Fountain Valley, Hesperia, San Pablo, and San Ramon). Regarding the sample’s 139% efficacy for market-rate housing needs, twenty cities achieved 100% or more of their allocated market-rate housing needs. Of that subset, the average MHI was $73,749, with only six cities maintaining MHIs that were below $50,000. This subset of twenty cities exceeded their allocated market-rate housing needs due to their lower quantities of allocated housing growth. Regarding the sample’s 67% efficacy for overall housing needs, the period of study covers 2007–2014 and this period coincides with the great housing recession (e.g., 2006–2013). In addition, the sample’s overall housing needs consisted of 60% as low-income housing. The deficit of low-income housing production reduced to the sample’s overall efficacy.

Regarding the 84% efficacy for potential ADUs overall, homeowners financed and produced these units and were not reliant on government funding. The primary source of funding for ADU production was the equity in the homeowner’s residence. As noted in the research, homeowners construct ADUs for additional income and ADU rent could be used to qualify for ADU production loans [

116]. In addition, many units were created through amnesty programs that legalized informal units with permits (e.g., Daly City, Encinitas, Lafayette, Los Gatos, Ojai, Petaluma, and San Carlos). Regarding the 0% efficacy for ADUs as low-income housing, CAHCD should assert its agency power and remedy this issue. At present, CAHCD oversees the evaluation of nearly 535 housing plans with a limited staff. However, the agency staggers its review of housing plans by region. When CAHCD finds that any city has counted potential ADUs towards low-income housing needs, then the agency should require that the city provide evidence of low-income covenants that will regulate the ADUs maximum rent, occupant-income, or effective period. If there is no legal evidence, then CAHCD should shift the city’s count of potential low-income ADUs to market-rate units and then direct the city to implement other planning tools to satisfy the outstanding low-income housing needs. This modification in administrative procedures should close the loophole of California’s Faustian Bargain. Closing this loophole is especially important in light of the recent 2017 ADU mandate revisions and the subsequent increase in ADU applications.

In order to determine whether ADUs are suitable as low-income housing, this study call for research on

verified and

permitted low-income ADUs in light of California’s rising housing costs. If low-income ADUs persist, then what was the legal mechanism? If these units did not persist, then what should planners do differently? The City of Santa Cruz is a case in point. From 1986 to 2017, Santa Cruz approved 444 ADUs and restricted 13.5% (or 60) of those units as low-income housing [

68]. However, only 29 low-income ADUs persist because the homeowners have repaid the waived fees that initially restricted the ADU’s maximum rent. Furthermore, in 2015, Santa Cruz proposed income and occupancy limitations on ADUs due to the rise of the sharing economy [

163,

164,

165]. However, the council encountered strong resistance from homeowners, who insisted that unregulated ADU income was necessary to supplement homeowner income. These points do not bode well for the cities of Piedmont, CA, USA or Pasadena. In their response to the 2017 ADU mandate revisions, both cities are experimenting with ADUs as low-income housing. Piedmont recently modified its city’s zoning code and can impose low-income covenants on ADUs. In Pasadena, the city aimed to incentivize ADU production by reducing permit fees from roughly

$20,000 to

$1000 per unit

if the homeowner agrees to a seven-year ADU rent restriction [

166]. Only time will tell whether Piedmont or Pasadena is successful in increasing the housing options for low-income households.

This study explored the conditions that influence the implementation of ADUs in California cities and the regression tests indicated that sample cities with colleges and high household incomes were positively associated with counting potential ADUs towards overall housing needs and ADUs as low-income housing. Regarding colleges the positive associations were not surprising, given that the following cities classified students as low-income households, described ADUs as student housing, and/or identified working with their respective colleges to increase student housing on campus or within the city itself: Davis (UC Davis), Moraga (Saint Mary’s College), Palo Alto (Stanford University), Pleasant Hill (Diablo Valley Junior College), San Marcos (California State University San Marcos), San Pablo (Contra Costa College), and Santa Clara (Santa Clara University, Mission College).

The positive consistency of income, however, seems to conflict with the literature, which maintains that high-income cities resist low-income housing. However, this prevalence is not a conflict if you adopt a California city’s view. In California, housing demand is constant. Due to the Housing Element Law and the ADU mandate, cities must accommodate low-income households and counting potential ADUs procedurally satisfies low-income housing needs and complies with state law. From an exclusionary view, which of the following is worse: counting a potential ADU occupied by one household or zoning multifamily land to facilitate an apartment building that would be occupied by multiple households that may require increased educational and social services? I suggest that counting a potential ADUs as low-income housing is more favorable to exclusionary cities than potential apartments. As a result, these cities may take a calculated risk owing to CAHCD’s lenient assessment of potential ADUs as per the housing plans for the cities of Folsom, Malibu, Moraga, San Marcos, and San Ramon.

Regarding the significant variables that were negatively associated with ADU production, density was understandable but compliance was a surprise. Regarding density, California allows ADUs on all residentially zoned land. However, many cities restrict ADUs to single-family residential zones, as found in the sample. Thus, density’s negative relationship is understandable given that cities with higher overall densities would be unlikely to allow ADUs along with other zoning requirements for multifamily housing units (e.g., open space per unit, sprinklers, occupant and guest parking, design review, stormwater retention). A notable exception is the City of San Francisco, which prohibited ADUs from 1982 to 2016.

Regarding

compliance, the negative relationship suggests that cities that adhered to state law and provided suitable zoning to facilitate housing production for roughly 5½ years (out of nine years) may have delivered suitable housing for various households in all economic segments. In turn, these cities may have lessened their dependence on ADUs to satisfy housing needs. Four points support this assertion. First, the collective fair-share housing allocations in the examined urban regions directed 60% of housing growth to cities with MHIs of less than

$50,000. Second, the sample’s lower-income cities were less likely to count potential ADUs overall and as low-income. Third, Ramsey-Musolf’s recent study determined that California cities employed a wide variety of planning tools to accommodate housing needs. In that study, the top five planning tools were zoning (adoption and/or amendments), residential rehabilitation to remove defects, identification of sites with appropriate densities, identification of sites for transitional housing (e.g., homeless, women’s, or emergency shelters) and, modification of development standards to facilitate production [

92]. Lastly, the sample’s low-income cities’ housing plans averaged the highest compliance rates at 67% (or roughly compliant for 6 out of 9 years). Thus, the sample’s lower-income cities may have implemented multiple planning tools to accommodate not only regional housing growth but also low-income housing needs.

Regarding

potential ADUs, this is the first study that has quantified and tested this variable as it relates to

ADU production. The analysis indicates that

potential ADUs are positively associated with increased

ADU production. This analysis suggests that when planners count potential ADUs, this planning exercise is more influential on ADU production than the city’s MHI or the presence of a college, for this sample. Given the research that calls for flexible ADU zoning [

3,

18,

52,

78], this study provides evidence that supports California’s 2017 revisions to the ADU mandate. These revisions should motivate planners to increase the housing options for diverse households and as a side benefit, ADUs will provide additional income for homeowners.

Regarding the significant variables associated with

ADU production, the direction and magnitude of

Renters is interesting given the negative relationship of

density, which describes the city’s housing fabric. In this study,

Renters measures the proportion of occupied rented housing units; however, that statistic includes a variety of housing types (e.g., single-family, duplex, triplex, four units and higher). Therefore, each city’s

renters statistic may measure both rented multifamily units and single-family homes. As noted by Pfeiffer, moderate-incomes cities that desired to be “dynamic and environmentally sustainable” have positioned ADUs as a method to capture the housing market segment that wants to live in “in denser, diverse and more walkable communities” [

45]. When

renters and

density are coupled with

potential ADUs, one might suggest that when cities plan for rental housing, this planning effort also creates opportunities for ADU production because these cities have embraced housing diversity and growth. Lastly, this paper argued that the sample’s California cities have imposed discretionary authority via

development constraints, but this variable was not significant in any test. Even though

Table 1 indicates that 70% of the sample maintained at least one constraint, the measurement in this study relied on current zoning. Therefore, the tested variable may have not have been in effect during the study period.