4.1. Settings

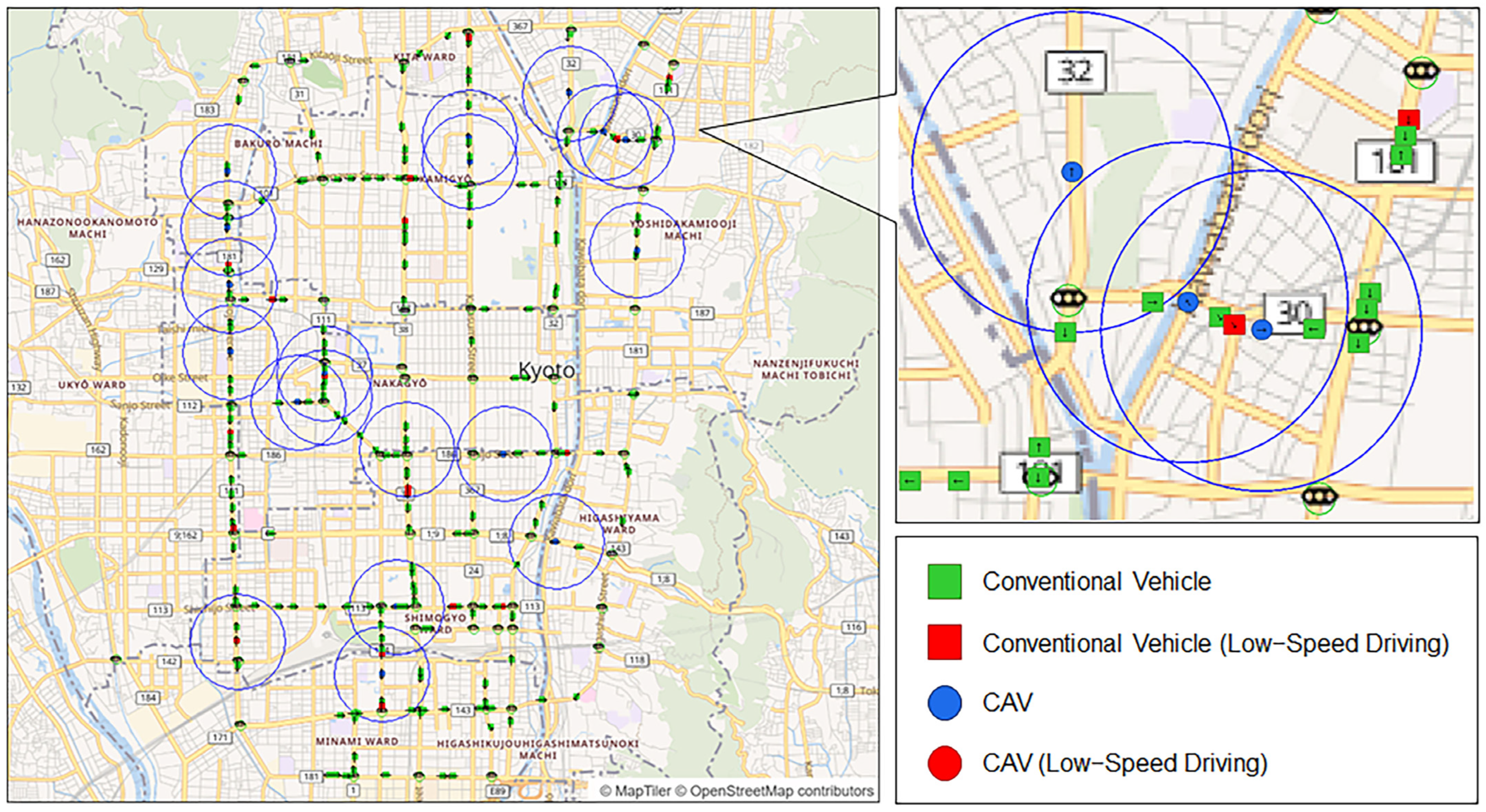

The simulation was conducted using Kyoto City as an example of a real urban environment. The simulation used artisoc, a platform for multi-agent simulation developed by [

43]. The simulation interface is shown in

Figure 4. Vehicle agent markers and colours distinguish between conventional vehicles and CAVs, and also indicate low-speed driving conditions. The communication range of each CAV is indicated by a blue circle.

In the simulation, we used a road network extracted from national highways (trunk), major prefectural roads (primary), and general prefectural roads (secondary) in Kyoto (

Figure 5). All of these are major roads that carry high traffic volumes and form the structural backbone of urban traffic within the study area (note that motorways are not included in the target region). In contrast, this study omits municipal roads (classified as tertiary and unclassified) from the model, which constitutes an important simplification that may affect congestion patterns and route choice behaviour. In particular, excluding fine-grained street networks may lead to an underestimation of drivers’ detour behaviour and the mechanisms underlying localised congestion. The results of this study should therefore be interpreted as an analysis focused primarily on major roads. The road network in Kyoto comprises 112 points (nodes) and 152 roads (links).

The parameters governing the driving behaviours of vehicle agents were set as follows: maximum speed vmax = 1, acceleration a = 0.334, and minimum safe distance dmin = . The maximum speed is normalised to 1, which corresponds to 60 km/h. Given that one simulation step represents 3 seconds in real time, an acceleration value of 0.334 corresponds to approximately 1.86 m/s2, which is comparable to typical passenger vehicle acceleration performance (1.5–3.0 m/s2). As a result, the safe following distance varies with driving speed, and when travelling at the maximum speed, the safe distance corresponds to 27.75 m. In addition, because the maximum standard travel time was 248, data collection was initiated after 250 steps and terminated once 3000 vehicles had reached their destinations. Although a larger number of vehicles reaching their destinations would improve the statistical stability of the simulation results, the number was set to 3000 considering the trade-off with computational time.

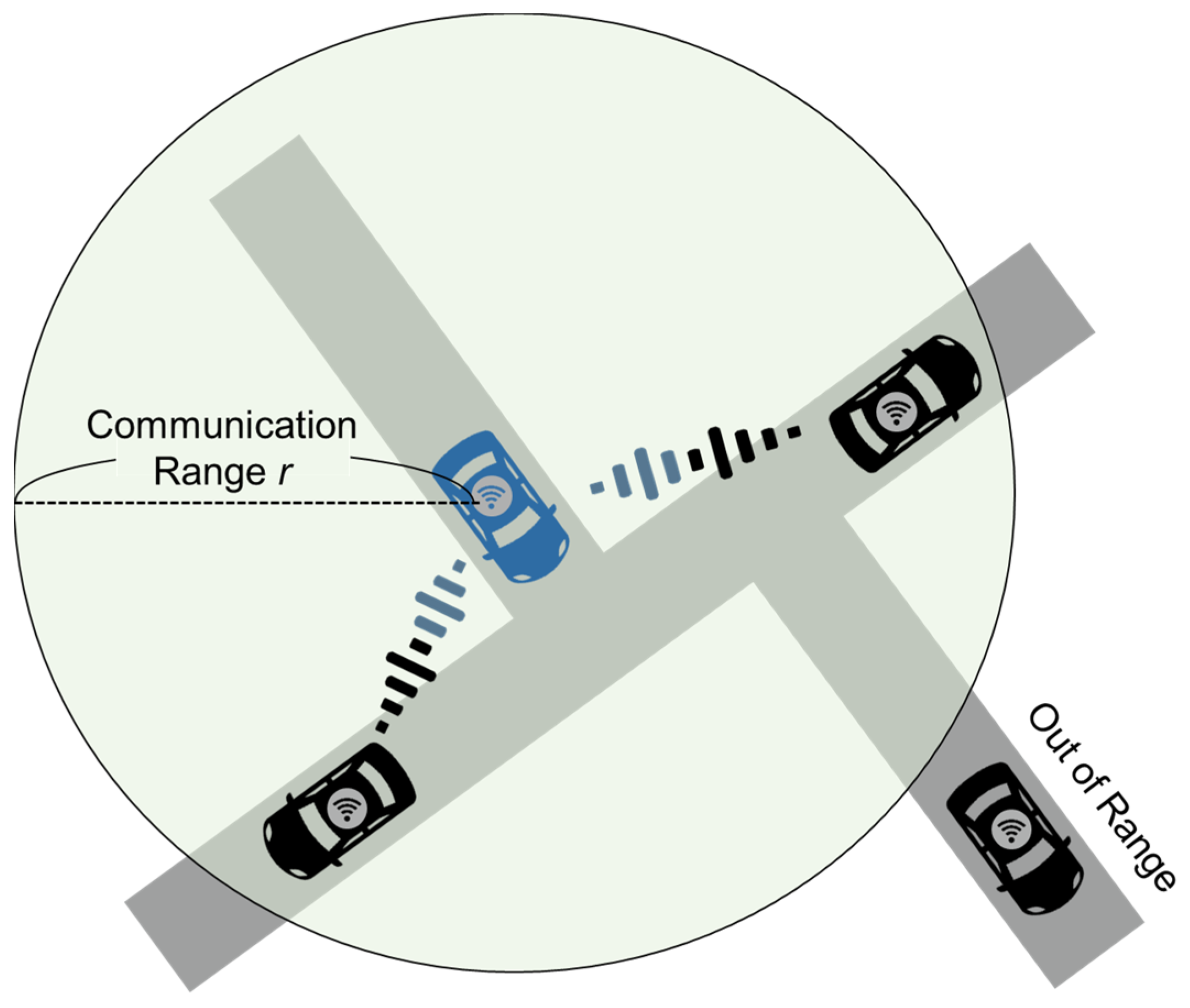

In the simulation, the communication range of the CAVs was varied in increments of 10 from a radius of 10 to 100, and the penetration rate of the CAVs (generation ratio) was varied in increments of 5% from 0% to 100%. A penetration rate of 0% represents a scenario in which the vehicle agents are conventional vehicles, whereas a penetration rate of 100% corresponds to a scenario in which all agents are connected.

The generation probability of vehicle agents is determined by the population assigned to each road endpoint (node). It is assumed that nodes associated with larger populations generate vehicle departures more frequently. The population assigned to each node was based on the “500-m Mesh Estimated Future Population Data (FY2018 National Government Office Estimate)” obtained from [

44].

Figure 6 presents a colour-coded map of population density, in which warmer colours represent areas with higher population levels, while cooler colours indicate areas with lower population levels. The population within each mesh block was allocated to the nodes contained within that block, and the population assigned to each node was proportionally determined based on the number of nodes in the mesh.

The probability that a vehicle agent is generated with node

i as its origin is given by:

where

δ is a scaling parameter used to adjust the overall traffic volume in the simulation. In the simulation for Kyoto City,

δ was set to 0.25 in considering the numbers of nodes and the total number of generated agents.

Similarly, the destinations of the generated vehicle agents were determined probabilistically based on the population. The traffic demand between nodes was determined by the following gravity model, which is based on the population

Pi of origin node

i, population

Pj of destination node

j, and the straight-line (Euclidean) distance

Lij between the two nodes.

Here,

σ1,

σ2, and

σ3 represent parameters of the gravity model, set as

σ1 = 0.5393192,

σ2 = 0.3702117, and

σ3 = 1.666391, based on estimates from data on Japan’s three major metropolitan areas as reported by [

45].

The probability that a vehicle agent generated at the origin node

i has node

j as its destination is then given by:

It should be noted that the demand generation method employed in this study is not intended to reproduce actual commuting and school travel behaviour, tourist traffic, time-of-day demand variations, or empirically observed congestion patterns in Kyoto City. The parameters of the gravity model are estimated based on data from other metropolitan areas and therefore do not directly reflect Kyoto-specific land-use structures or travel behaviours. As a result, the O/D demand generated by this model may not necessarily coincide with real-world traffic demand or the actual locations of congestion.

In this study, demand generation is positioned as a conceptual experimental setting designed to examine how differences in CAV communication range and information-sharing mechanisms influence route choice and traffic flow distribution. The population-based gravity model is adopted as a parsimonious approximation capable of capturing the global spatial imbalance of O/D demand, rather than for the purpose of quantitatively reproducing real traffic conditions. Accordingly, the results presented below should be interpreted as relative comparisons under common demand conditions, rather than as assessments of the absolute validity of demand levels or congestion locations.

Future research should aim to construct more realistic demand models by incorporating Kyoto-specific O/D survey data or empirically observed mobility data derived from smartphones or GPS, thereby further refining the simulation results.

4.3. Two-Way ANOVA

In this section, a two-way analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA) is conducted to examine whether the two design parameters—the CAV penetration rate and the communication range—lead to systematic differences in the average level of total CO2 emissions.

The ANOVA employed here is not intended to provide a rigorous estimation of causal effects or a precise quantification of effect sizes. Rather, its purpose is to serve as a supplementary check to determine whether the nonlinear and level-dependent patterns identified through visualisation and curve-fitting analyses in the preceding and subsequent sections can also be detected as consistent differences at the level of mean values.

Table 4 presents the results of the two-way ANOVA assessing the effects of CAV penetration rate and communication range on total CO

2 emissions. The analysis reveals a very large and statistically significant main effect of the CAV penetration rate (F = 1388.72,

p < 0.001), indicating that the average level of CO

2 emissions differs substantially across penetration levels. This result suggests that, as the penetration of CAVs increases, the mean emissions level changes in a systematic manner.

A statistically significant main effect is also observed for the communication range (F = 32.27, p < 0.001). This finding indicates that, even when averaging across penetration rates, differences in communication distance are associated with consistent changes in the average level of CO2 emissions.

In addition, the interaction term between penetration rate and communication range is statistically significant (F = 2.51, p < 0.001). This result implies that the effect of communication range on CO2 emissions varies depending on the level of CAV penetration, and conversely, that the influence of penetration rate manifests differently across communication conditions.

These patterns can also be visually confirmed from the main-effect and interaction plots shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. As illustrated in

Figure 7a, total CO

2 emissions exhibit an overall decreasing trend as the CAV penetration rate increases. In contrast, the main effect of communication range shown in

Figure 7b indicates that the improvement becomes apparent as the range expands from short to medium distances, while changes become more gradual beyond a certain level.

The interaction plot presented in

Figure 9 further shows that the effect of communication range varies depending on the level of CAV penetration. Taken together, these results suggest that the influences of communication distance and penetration rate do not operate as simple linear effects, but rather emerge through level-dependent and non-linear structures.

Overall, the results of the two-way ANOVA confirm, at the level of mean values, that both CAV penetration rate and communication range are systematically associated with CO2 emissions. In this sense, the ANOVA serves as a preliminary validation that motivates the subsequent analysis of non-linear change patterns examined in the following section.

4.4. Curve Fitting

The preceding ANOVA confirmed that there are systematic differences in the mean level of CO

2 emissions associated with variations in both the CAV penetration rate and the communication range. In this section, we descriptively examine how these differences manifest as non-linear structures over the process of increasing CAV penetration by applying logistic growth curve fitting (details of the model selection based on comparisons with alternative growth models are provided in

Appendix C).

The purpose of the logistic model in this study is not to estimate strict causal relationships or to generate forecasts. Rather, it is employed as a descriptive tool to summarise characteristic patterns in the CO2 emission reduction process—namely the onset, acceleration, and saturation of reduction effects as the CAV penetration rate increases.

Specifically, total CO

2 emissions

were scaled using Min–Max normalisation based on the minimum value

and the maximum value

. The scaled total CO

2 emissions

can be estimated as a function of the CAV penetration rate

x using the following equation:

Here, represents the upper asymptote, is a coefficient that controls the slope of the curve, and denotes the inflection point. In this study, because is normalised by its maximum value, is fixed at 1 for estimation.

The logistic growth model is originally used to describe processes such as population growth and technology diffusion; in this study, it is adopted not as a strict causal model but as a descriptive approximation for summarising the pattern of changes in CO2 emissions. Accordingly, the estimated parameters and should not be interpreted as direct measures of the magnitude of emission reduction, but rather as indicators that characterise how rapidly the reduction effect emerges and at what level of CAV penetration the system reaches a turning point.

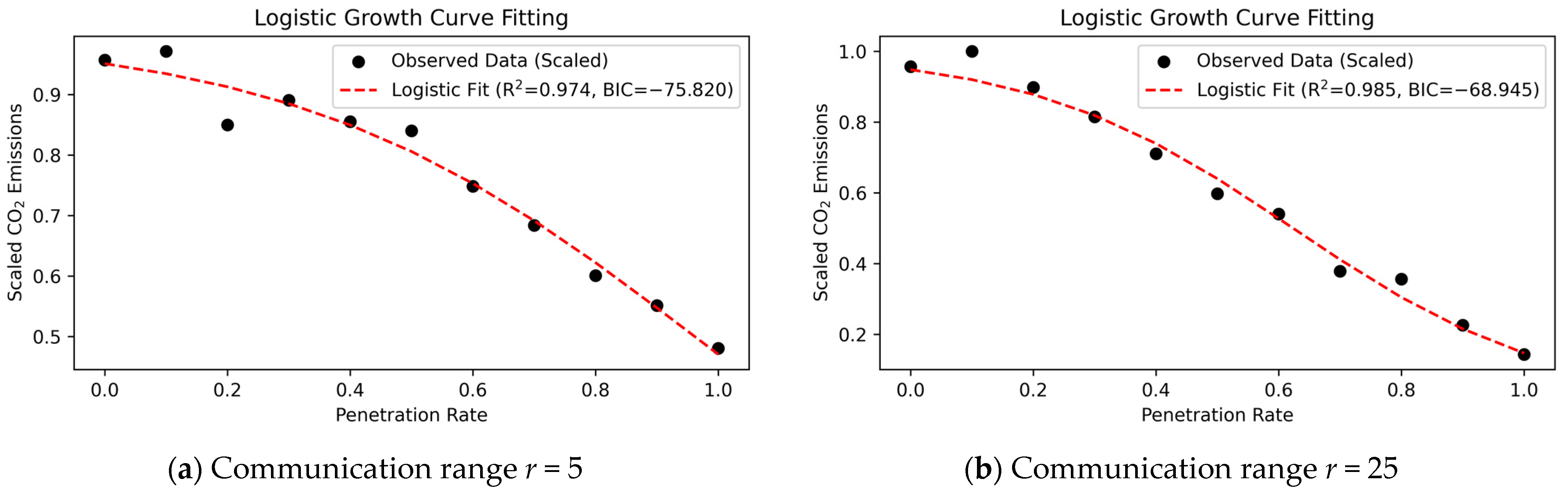

As shown in

Table 5, the coefficient of determination R

2 exceeds 0.9 for all communication ranges, indicating that the logistic curves provide a generally good approximation of the simulation results. This suggests that the CO

2 reduction effect associated with increasing CAV penetration shares a common nonlinear structure across all communication ranges, characterised by limited effects at low penetration levels, relatively pronounced reductions at intermediate levels, and eventual saturation at higher penetration rates.

By contrast, the estimated values of

and

vary across communication ranges, suggesting that the onset and saturation of the CO

2 reduction effect depend on communication conditions. When the relationship between total CO

2 emissions and the CAV penetration rate is illustrated graphically, cases with

and small |

β| exhibit a gradual inverted S-shaped curve (

Figure 9a), whereas cases with

and large |

β| display a steeper inverted S-shaped curve (

Figure 9b). In particular, when the communication range exceeds 25, the magnitude of |

β| approaches approximately 5, and the logistic curves become relatively steep. This result indicates that once a certain minimum communication range is ensured, the CO

2 emission reduction associated with increasing CAV penetration tends to emerge more rapidly.

However, for communication ranges of 20 or less, the estimated inflection point takes relatively high values, indicating that a high level of CAV penetration is required before the reduction effect becomes apparent.

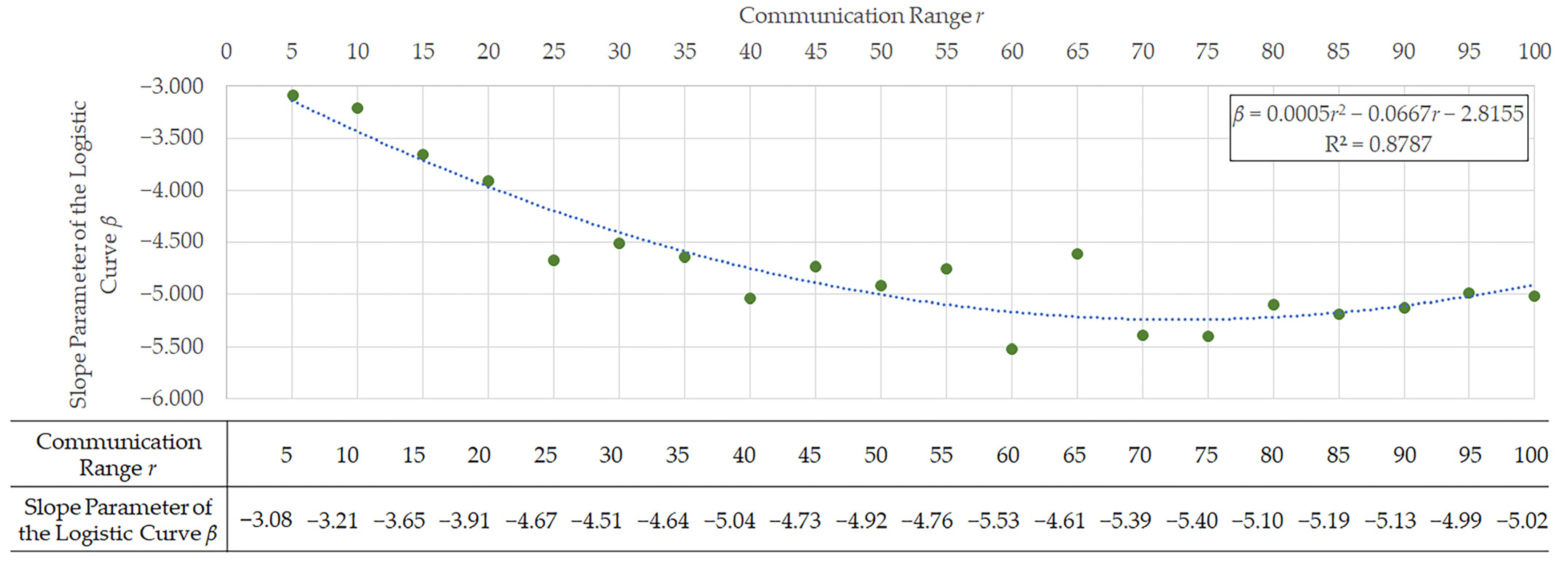

Next, we examine the relationship between the communication range

and the speed at which the CO

2 reduction effect emerges, as captured by the parameter

. As shown in the table in

Figure 10, the absolute value of

does not change monotonically with increasing communication range, but instead exhibits a nonlinear pattern. When the communication range is very small, an insufficient number of CAVs can exchange information, and the effects of communication are therefore unlikely to materialise. Conversely, when the communication range becomes excessively large, the emission reduction effect may become less responsive to increases in the CAV penetration rate.

This non-monotonic relationship is further confirmed by the fact that the relationship between the communication range

and

can be well approximated by a quadratic function (details of the comparison with other models are provided in

Appendix D), as illustrated in the graph in

Figure 10.

In this study, the observed behaviour is interpreted through the contrasting concepts of swarm intelligence and information homogenisation. Here, swarm intelligence does not refer to any specific cooperative algorithm or explicit form of collective optimisation. Rather, it denotes a more general mechanism whereby, under conditions in which individual vehicles make selfish decisions based on spatially limited local information, information incompleteness and heterogeneity can collectively promote traffic dispersion.

When the communication range becomes excessively large, the traffic information acquired by individual CAVs gradually converges, leading to overly homogeneous route choice behaviour. Under such conditions, vehicles are more likely to select the same or similar shortest routes, increasing the likelihood that traffic which would otherwise be dispersed becomes concentrated on specific routes. This phenomenon is consistent with established insights from traffic flow theory, which show that route choice under complete information converges to a user equilibrium corresponding to Wardrop’s first principle, while such an equilibrium is not necessarily socially optimal.

By contrast, when the communication range is moderately constrained, spatial differences arise in the sets of information available to individual vehicles, and heterogeneity in route choice information is preserved. Under such conditions of imperfect information, decentralized decision-making can, as an emergent outcome, promote the spatial dispersion of traffic flows and mitigate the concentration of congestion and emissions at the network level. Foundational studies such as Schelling’s segregation model [

26] and Reynolds’ Boids model [

27] provide useful theoretical backgrounds for interpreting this mechanism, as they demonstrate how localized and slightly heterogeneous information or behavioural rules can give rise to ordered patterns at the collective level.

In summary, the CO2 emission reduction effects observed in this study are not predicated on centralised control or complete information sharing. Rather, they can be interpreted as emerging from the interactions of decentralised behaviours induced by the design of the information structure, specifically the communication range. Nevertheless, these interpretations are qualitative in nature and are based on a simplified modelling framework; they do not claim the general validity of swarm-intelligence-like effects. Instead, the findings should be understood as a conceptual illustration of how the balance between information homogenisation and heterogeneity can influence traffic flow under the specific conditions considered in this study.