1. Introduction

As economic globalization deepens, urban agglomerations have become the core spatial vehicles through which countries participate in global competition and steer future development, and represent the highest spatial form of urbanization [

1]. The traditional “space of places” analytical paradigm based on static city attribute data can no longer fully reveal the complex functional linkages and dynamic evolution mechanisms within urban agglomerations [

2]. Against this backdrop, the “space of flows” theory, which takes the movement of factors as its core, has emerged, viewing urban agglomerations as complex networked systems woven by multiple factor flows, and has become a frontier topic in regional science and urban geography [

3,

4].

Within this network-oriented research paradigm, scholars have conducted extensive and in-depth studies of urban networks based on different types of factor flows. In terms of economic linkages, many studies use enterprise “headquarters–branch” data, inter-firm investment relations and transactions in goods to characterize economic networks, revealing the hierarchical structure, core–periphery patterns and sectoral heterogeneity of urban agglomeration economies [

5,

6,

7]. From the perspective of information linkages, information flow data represented by the Baidu Index have been widely employed to measure inter-urban information network connections and to analyze spatial organization patterns such as “axis–belt driven” and “centre–hinterland” structures [

8,

9,

10]. In addition, multiple other factor flows, including high-speed rail flows, population migration, scientific and technological cooperation and air transport, have been used to construct urban networks from different dimensions, greatly enriching our understanding of spatial interactions within urban agglomerations [

11,

12,

13,

14].

However, a single-dimensional factor network can only depict a specific facet of relationships within an urban agglomeration, whereas real-world urban systems are complex mega-systems in which multiple networks are interwoven and coupled [

4,

15]. Some studies have begun to focus on the comparison and interrelation of multi-dimensional networks. For example, scholars have examined the dynamic coupling between high-speed rail networks and inter-regional investment networks [

16], or comparatively analyzed the similarities and differences between high-speed rail flows and information flows in network evolution [

17]. These studies indicate that there are significant similarities and differences among different types of networks, and that their coupled interactions jointly shape the overall spatial pattern of urban agglomerations [

18]. Among them, the economic network constitutes the core skeleton of urban agglomeration development, reflecting the tangible linkages of capital, industry and services [

19], whereas the information network serves as a virtual channel for regional knowledge diffusion and innovation collaboration, capturing the soft connections and influence between cities [

8]. Economic activities and information exchanges are becoming increasingly inseparable, and the degree to which they are coupled directly affects the depth and quality of coordinated development in urban agglomerations [

15].

Studies on urban agglomeration networks at home and abroad provide important references for understanding different structural types. The Northeastern United States urban agglomeration has developed a multi-centre, networked spatial organization pattern [

20,

21]. The Rhine–Ruhr urban agglomeration in Europe is characterized by multiple cores and decentralization, and exhibits strong network resilience. By contrast, the Tokyo metropolitan area in Japan displays a highly monocentric pattern [

22,

23,

24]. Beyond such typological descriptions, empirical research in the United States and Europe has operationalized “network resilience” through robustness testing under random failures and targeted attacks, emphasizing redundancy and alternative routing in large urban transport systems [

25]. At the governance level, U.S. megaregion studies highlight collaborative, networked arrangements that cross jurisdictional boundaries to manage interdependencies and disruption response at supra-metropolitan scale [

26]. In Europe, policy and planning debates on polycentric development link multi-centre spatial organization with competitiveness–cohesion balancing at the city-regional scale [

27], while public-transport studies show that operational measures such as reserve capacity can mitigate disruption impacts and improve network robustness [

28]. However, international research has mostly focused on assessing the resilience of physical infrastructure networks (such as transport and energy), and has rarely examined their coordination mechanisms and resilience characteristics from the perspective of multi-layer network coupling between economic and information systems [

29].

In China, the three major urban agglomerations—the Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta and Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei—show marked heterogeneity. The Yangtze River Delta has formed a multi-centre, hierarchical structure that is close to the pattern of mature international urban regions [

30,

31,

32]. The Pearl River Delta (Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area) presents a multi-core linkage pattern, where the Shenzhen–Hong Kong–Guangzhou innovation corridor is highly internationalized and inter-city industrial chains are tightly coupled. In contrast, the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei urban agglomeration manifests a typical mono-centric network structure dominated by Beijing. The growth rate of its inter-city enterprise investment network is only 19%, network density remains low and hierarchical differentiation is pronounced; administrative boundaries still create barriers to the formation of inter-city links and lead to imbalances in resource allocation, and the overall degree of networkisation needs to be improved [

33]. This distinctive stage of development makes Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei an ideal case for studying network evolution, coupling mechanisms and resilience enhancement in urban agglomerations undergoing transformation.

At the same time, the complexity and coupling of networks bring new vulnerabilities. As a closely connected whole, an urban agglomeration is subject to the risk that local node failures or external shocks may propagate through networks, trigger chain reactions and affect the stability of the entire system [

20,

21]. Therefore, “resilience”—as a key concept for assessing the capacity of a system to withstand shocks, maintain functions and recover or adapt—has been introduced into urban network research [

34]. Extending this view to inter-city linkages in an urban agglomeration, urban agglomeration network resilience refers to the capability of the inter-city flow network to sustain basic functioning and element-exchange capacity when some nodes/links are disrupted, supported by redundancy and alternative paths [

15]. Existing studies have attempted to construct urban resilience evaluation frameworks from the perspective of multi-dimensional associated networks in the economic, social and ecological domains, or to identify vulnerable links by analyzing urban material metabolism networks [

22,

24]. Nevertheless, there is still a lack of research that integrates the two themes of network “coupling” and “resilience”, and, in particular, systematic and dynamic simulations and evaluations of the resilience of the core economic–information coupled network remain scarce [

35].

Against the backdrop of the deep implementation of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei coordinated development strategy, sudden events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and supply-chain disruptions have further highlighted the importance of network resilience in urban agglomerations. As a key national strategic region in China, the internal network structure of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei urban agglomeration has attracted sustained attention. Although under the coordinated development strategy, the network pattern is evolving from a monocentric radiation structure towards a more complex multi-centre configuration [

36], how the economic and information networks are coupled and coordinated, and how such coupling structures affect the resilience performance of the entire urban agglomeration when facing disturbances, are scientific questions that urgently require further investigation.

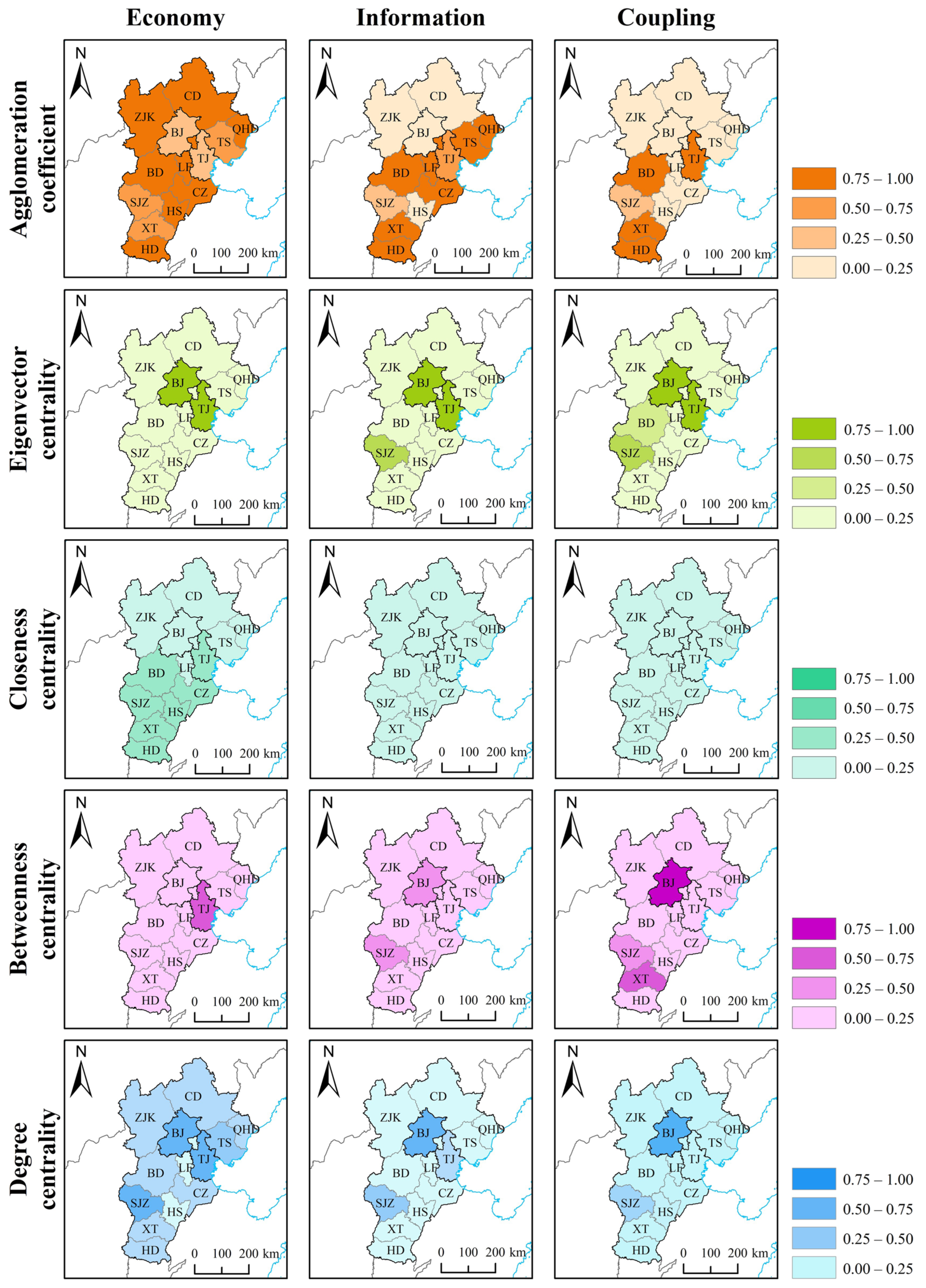

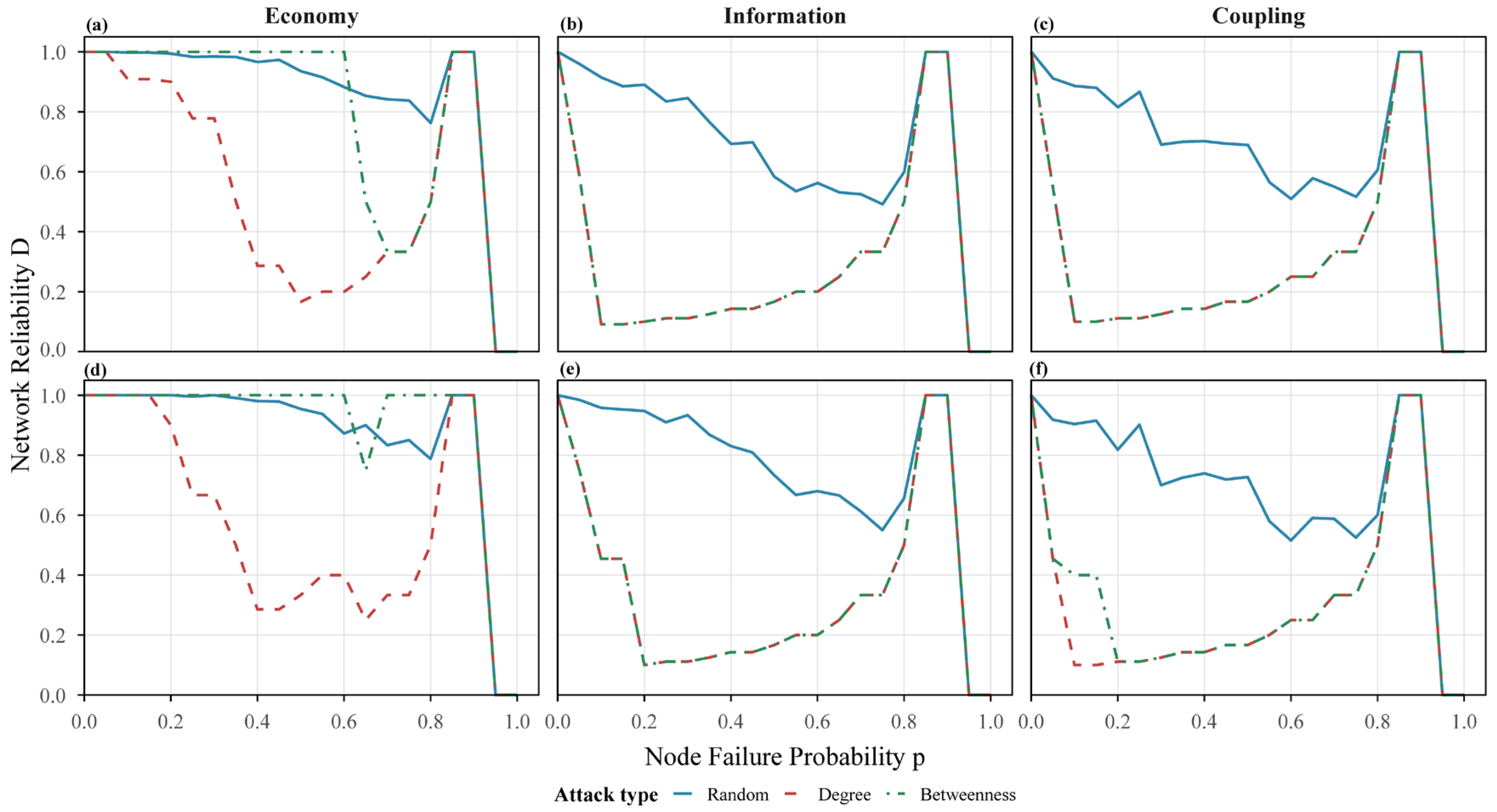

In summary, existing studies have advanced our understanding of urban agglomeration networks, yet several gaps remain when economic and information flows are considered jointly from a resilience perspective. First, economic and information networks are often examined separately, and their consistency is frequently inferred from aggregate indicators, leaving the overlap and divergence of strong ties and their evolution within the same urban agglomeration underexplored. Second, although “coupling” has been widely discussed, coordinated coupling between economic and information networks is rarely quantified in a way that simultaneously considers interaction intensity and spatial configuration. Third, resilience assessments still rely largely on static robustness descriptions, and comparatively few studies provide dynamic evidence on how coupling shapes vulnerability under different disruption mechanisms (e.g., random failures versus targeted attacks). In view of these gaps, this study takes the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei urban agglomeration as the case area and constructs economic and information linkage networks based on inter-firm investment data and online information attention data. Social network analysis is employed to depict the spatial structural characteristics of the two networks. On this basis, a coupling coordination model is developed to quantify the coupling and differentiation patterns of the economic–information network. Finally, by simulating deliberate attacks and random failures, the dynamic resilience of the coupled network is evaluated to provide decision support for enhancing regional urban network resilience.

4. Evolutionary Mechanisms and Theoretical Interpretation

On the basis of the above quantitative analysis, we find that between 2013 and 2023 the economic, information and coupled networks of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei urban agglomeration follow a complex evolutionary path that is at once coordinated and differentiated in terms of structure and resilience. To gain a deeper understanding of this phenomenon, this section carries out a systematic mechanism analysis and theoretical interpretation from three perspectives: the external driving forces of network evolution, the internal mechanisms of coupling coordination, and the deep-seated causes of resilience differentiation.

4.1. Driving Forces of Network Evolution

4.1.1. External Driving Forces: Coordinated Advances in Policy, Market and Technology

The increase in density and link strength of the economic, information and coupled networks in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region is the result of the joint action of three major external driving forces: policy guidance, market forces and technological change.

First, at the policy level, the state-led promotion of regional integration has been decisive. The top-level design provided by the Outline of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Coordinated Development Plan (approved in 2014), together with subsequent major policies such as the relocation of Beijing’s non-capital functions, the establishment of Xiong’an New Area in 2017, and the construction of Beijing’s sub-city centre, has substantially reduced administrative barriers to the flow of factors between cities. With both mandatory and guiding effects, these policies have not only directly promoted the establishment of intergovernmental coordination mechanisms, but have also driven cross-jurisdictional restructuring of industrial chains. For example, the continuous expansion of “cross-provincial processing” of government services among the three regions has already covered 234 items, and 179 items now share unified procedures and standards. This has greatly strengthened the interconnection of economic and information factors, providing a fundamental impetus for the continuous increase in the number and density of network edges.

Second, at the market level, industrial relocation and cost gradients have driven spatial restructuring. Long-standing differences in factor costs within the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region form an endogenous economic impetus for network evolution. High costs in Beijing have pushed manufacturing and parts of the service sector to relocate to places such as Baoding, Langfang and Cangzhou, while Hebei’s advantages in land and labour have attracted spillover investments of capital from Beijing and Tianjin. This market-driven process of industrial relocation and spatial restructuring has produced an economic network pattern of “Beijing–Tianjin core—coastal belt—hinterland followers”. It not only expands the economic linkage network, but also leads information linkages to strengthen in step with enterprise location decisions and market expansion.

Third, at the technological level, the synchronous development of transport and digital infrastructure has played a key role. Between 2015 and 2023, the improvement of high-speed and intercity rail networks such as the Beijing–Zhangjiakou, Beijing–Xiong’an and Tianjin–Baoding lines, together with the integrated development of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei airport and port clusters, has greatly compressed time–space distances between cities. Meanwhile, the rapid deployment of new information infrastructure, including 5G networks, data centres and cloud computing platforms, has substantially increased the carrying capacity and spatial reach of information flows. The completion of these technological infrastructures directly reduces the costs of information transmission, logistics and personnel movement between cities, and constitutes the most immediate external force driving the three networks to evolve from loose to dense structures.

4.1.2. Sources of Differences in Evolutionary Speed

Despite being subject to the same external driving forces, the three types of networks evolve at markedly different speeds. The fundamental reason lies in the different factor attributes and constraints on which each network depends.

The information network evolves the fastest because of its virtual nature. Information flows have extremely low marginal costs and nearly instantaneous diffusion speeds. Their transmission relies on internet infrastructure that can easily transcend administrative boundaries and geographical distances, and is only weakly constrained by physical space. The rapid diffusion of digital infrastructure and the leap in the level of social informatization enable the information network to expand and decentralize at lower cost and higher speed.

The economic network, by contrast, progresses steadily due to its material nature. Capital flows and industrial linkages are constrained by sunk costs, the rigidity of industrial structures, investment return cycles and institutional factors such as administrative approval, all of which entail strong adjustment inertia and high transaction costs. As a result, although the economic network continues to expand, it does so at a slow, roughly linear pace, following a more path-dependent evolutionary trajectory.

The development of the coupled network lags behind because of its coordination complexity. As the superposition of the economic and information networks, its evolution requires not only the strengthening of each individual network, but also coordination in terms of link strength and topology. However, in the current Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, the digitalization of economic activities remains incomplete and cross-regional information-sharing mechanisms are still underdeveloped. These problems prevent the superimposed linkages between economic and information flows from fully synchronizing, and thus the integration of the virtual and real economies proceeds more slowly than the self-reinforcement of every single network.

4.2. Mechanisms of Coupling Coordination

The correlation coefficient between the economic and information networks decreases from 0.924 to 0.863, showing a distinctive pattern of “still highly correlated but with weakening correlation”. This is mainly the result of the joint action of three sub-mechanisms: coordination, spatial factors and self-organization.

In the early stage (around 2013), information infrastructure coverage was uneven, and the spatial distribution of information flows depended heavily on the locations of economic activity. Enterprise investment and market expansion decisions were the main sources of information demand, leading to a high degree of overlap between the two networks. As information infrastructure became more widespread, the costs of obtaining and disseminating information fell sharply, and the spatial diffusion capacity of information flows gradually surpassed the physical constraints on economic flows (such as plant location and sunk capital). The information network thus began to acquire an autonomous evolutionary momentum. For example, growth in information flows driven by noneconomic factors such as public attention and digital public services led the two networks to remain highly correlated but with gradually weakening correlation.

Geographical proximity and functional complementarity significantly enhance coupling strength. For example, intensive commuting linkages and industrial cooperation between Beijing and Langfang or Baoding have created high-intensity economic–information coupling zones. The time–space compression effects brought about by the construction of the high-speed rail network further reinforce this spatial stickiness based on geographical proximity. However, administrative boundaries (such as those between Beijing and Hebei or between Tianjin and Hebei) still pose barriers to the free movement of some factors, especially high-end economic factors. It is noteworthy that information flows can partly bypass these administrative barriers and diffuse across regions, which causes the spatial configuration of the information network to diverge locally from that of the economic network and reduces the complete overlap of their spatial structures.

Urban network evolution generally exhibits a preferential attachment mechanism: core nodes with many existing connections (such as Beijing and Tianjin) can, by virtue of early resource accumulation and positional advantages, continue to attract new linkages and thus generate a Matthew effect, which is highly path-dependent. However, due to its low switching costs, the topological expansion of the information network proceeds much faster than that of the economic network. Peripheral cities such as Shijiazhuang and Handan can quickly enhance their centrality in the information network by building information hubs and participating in digital cooperation, but they are unable to challenge the positions of core cities in the economic network in the short term. This difference in self-organized evolutionary rates leads to a relative decline in the structural similarity between the two networks.

4.3. Deep-Seated Causes of Resilience Differentiation

4.3.1. Network Properties and Differences in Node Substitutability

Information network resilience has improved the fastest, the economic network is the most fragile, and the coupled network lies in between; the fundamental reason is that the three networks differ in their inherent properties and in the substitutability of their nodes. Information flows are characterized by low sunk costs, high replicability and immediacy, which are typical features of the virtual economy. When local nodes or links fail, information can quickly be rerouted and reconfigured through alternative channels.

The economic network, however, is constrained by capital specificity, fixed-asset investment and high switching costs; investment relationships and industrial chains cannot be easily adjusted or replaced in the short term, which leads to weak disturbance resistance. The coupled network bears both the flexibility of information flows and the inertia of economic flows, and therefore exhibits an intermediate level of resilience. Nodes in the information network (such as data centres and information gateway cities) have relatively standardized functions and strong substitutability, making it easy to form multi-centre, flat structures. By contrast, in the economic network, Beijing and Tianjin act as control centres for high-end capital, innovation and decision-making; their functions are highly specialized and exclusive, with very limited substitutability. This difference in node substitutability directly determines that it is easier for the information network to decentralize, whereas the economic network finds it difficult to escape structural dependence on core nodes.

4.3.2. The Dual Role of Core Nodes and Its Impact on Resilience

Core nodes (Beijing and Tianjin) play different roles in the three networks, which is a key factor shaping overall resilience. In the economic network, Beijing and Tianjin are irreplaceable efficiency centres and capital hubs that undertake most intermediary functions of the network. While this single-core-dependent structure enhances the efficiency of network operation, it also creates critical points of vulnerability: once they come under targeted attack, the network is easily segmented, resulting in the lowest overall resilience.

In the information network, Beijing and Tianjin remain important sources and hubs of information, but their core status is relatively weakened. The information weights of peripheral nodes such as Langfang, Shijiazhuang and Tangshan increase significantly, forming an effective multi-point support configuration. This means that Beijing’s core functions can be partially substituted, thereby enabling the information network to demonstrate higher stability and resilience under various disturbances.

In the coupled network, the bridging roles of Beijing and Tianjin remain prominent: Beijing dominates the coordination of virtual and real factors, while Tianjin links the coastal economic belt. Although this hub function improves the efficiency of coupling, it also transmits the vulnerability of core nodes into the coupled network, making its resilience fall between that of the economic and information networks. The dual role of core nodes as both efficiency centres and points of fragility in the coupled network is the direct reason why its resilience performance is intermediate.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary

This study investigates the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH) urban agglomeration using a two-layer network framework by constructing an economic network from inter-city corporate investment ties and an information network from online attention flows, and by deriving an economic–information coupled network via coupling coordination. Comparing 2013 and 2023, we find an increasingly evident structural gap: the information network expands faster and becomes more inclusive, while the economic network strengthens more steadily and remains more corridor- and core-dependent. Although the two layers remain strongly connected, local link organization diverges, and the coupled network tends to lag behind the more rapidly evolving information layer. Resilience assessment indicates that the information network gains robustness from decentralization and redundancy, whereas the economic network is more sensitive to targeted removals of core nodes and corridors; the coupled network exhibits intermediate resilience performance.

5.2. Implications and Policy Recommendations

The results imply that enhancing urban agglomeration resilience requires not only strengthening each layer independently but also improving the alignment between “virtual” interactions and “material” investment linkages so that expanding information connectivity can be translated into more balanced economic connectivity. Policies can prioritize the construction of cross-jurisdictional redundancy by shifting from a “single-corridor dominance” pattern to a multi-route connectivity structure. In practice, this means coordinating inter-city transport and logistics planning across administrative boundaries, promoting multi-hub network layouts, and supporting alternative corridors that can substitute core routes during disruptions. Cross-city emergency mutual-aid arrangements and joint contingency planning can be institutionalized so that functional connectivity is maintained even when key nodes or links are compromised, consistent with governance-oriented insights from urban and interdependent infrastructure resilience research.

The coupled network lags when information links intensify without a comparable strengthening of investment ties in the same relational space. Therefore, policy instruments should explicitly aim at converting high-frequency digital interaction into higher-quality economic cooperation. A feasible strategy is to build a cross-city project pipeline that bundles innovation, industrial collaboration, and investment facilitation into shared programmes, paired with interoperable approval processes and coordinated incentives for cross-city projects that include peripheral cities. Establishing shared databases for industrial resources, innovation platforms, and investment opportunities—together with unified standards for data exchange and public service interoperability—can reduce coordination costs and help align link organization across layers. Evidence from the urban network resilience literature suggests that redundancy and coordination capacity are central to sustaining functionality under disturbances, and the policy emphasis should be placed on strengthening these capacities at the metropolitan scale.

Given the differentiated vulnerability of the economic layer to targeted shocks, resilience-oriented regional planning can further emphasize risk diversification by reducing excessive dependence on a small set of core nodes. This can be advanced by developing functional complementarities among secondary cities, creating stable cross-city collaboration mechanisms for supply chains and innovation networks, and using regional performance evaluation to reward cross-boundary collaboration and redundancy building. Such measures can improve coupling coordination while avoiding a purely “connectivity expansion” approach that may raise volume without improving systemic robustness.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the analysis relies on two benchmark years (2013 and 2023), which limits the observation of intermediate dynamics and the identification of short-term responses to shocks or policy changes; future work should incorporate multi-year panels to capture continuous evolution. Second, the network size is relatively small (13 cities), which may affect the stability of certain indicators; thus, this study emphasizes comparative interpretations and supplements them with robustness considerations. Third, online attention flows and corporate investment ties are proxies of broader information and economic interactions; integrating additional datasets such as mobility, logistics, multi-platform information flows, and more comprehensive firm-to-firm transactions would enhance external validity. Finally, institutional explanations related to administrative segmentation are not yet fully quantified in this study; future research will operationalize “administrative barriers” using measurable network-derived and institutional proxies and embed them in statistical or causal designs to more explicitly test how such barriers shape multilayer coupling and resilience outcomes.