Beyond the Urban Heat Island: A Global Metric for Urban-Driven Climate Warming

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. State of the Art

2. Data, Model, and Method

2.1. Land Cover

2.2. Meteorological Forcing

2.3. Model Overview

2.4. Spatial Resolution and Temporal Scope

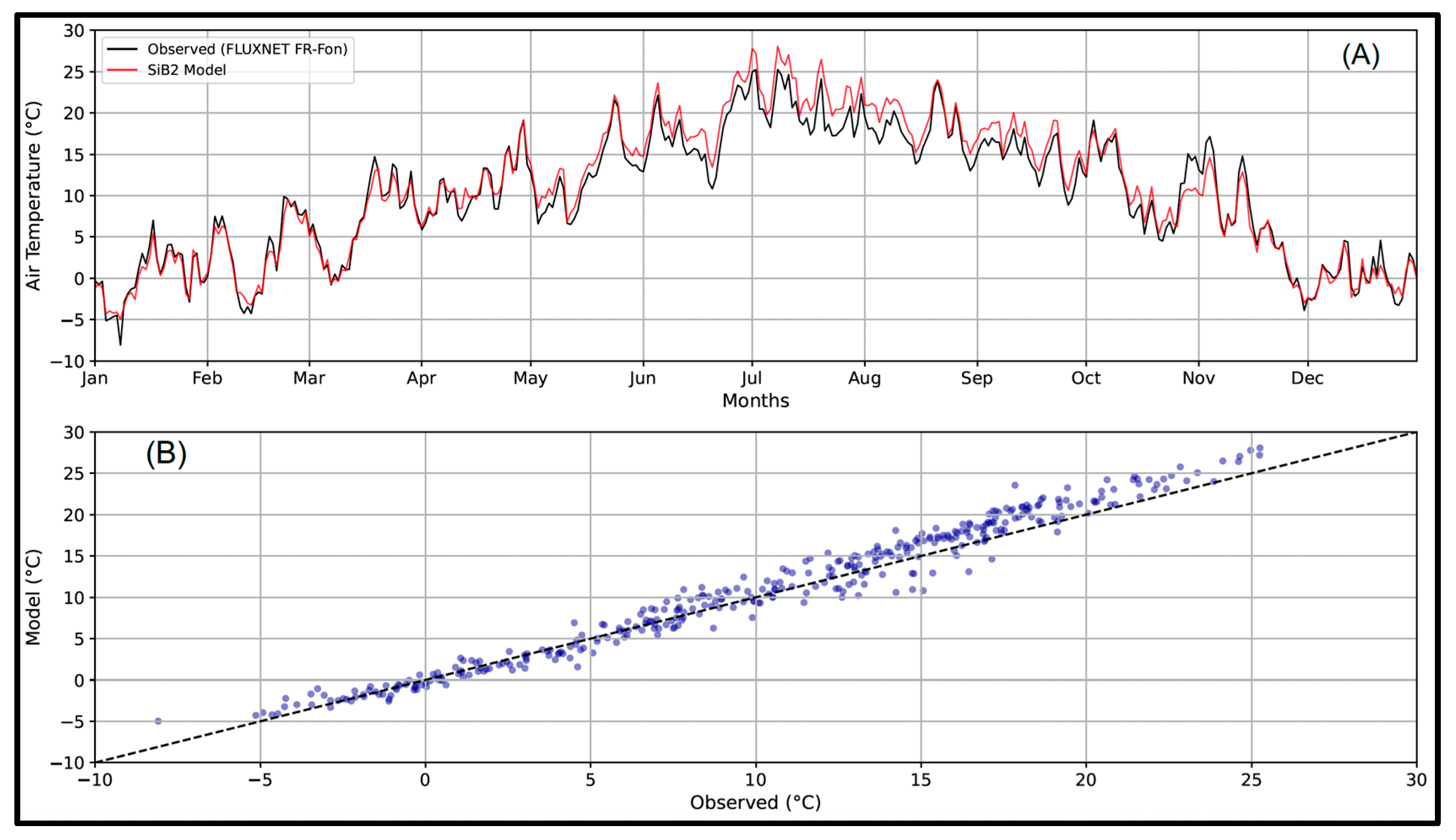

3. Model Evaluation

3.1. Validation Approach

3.2. Evaluation

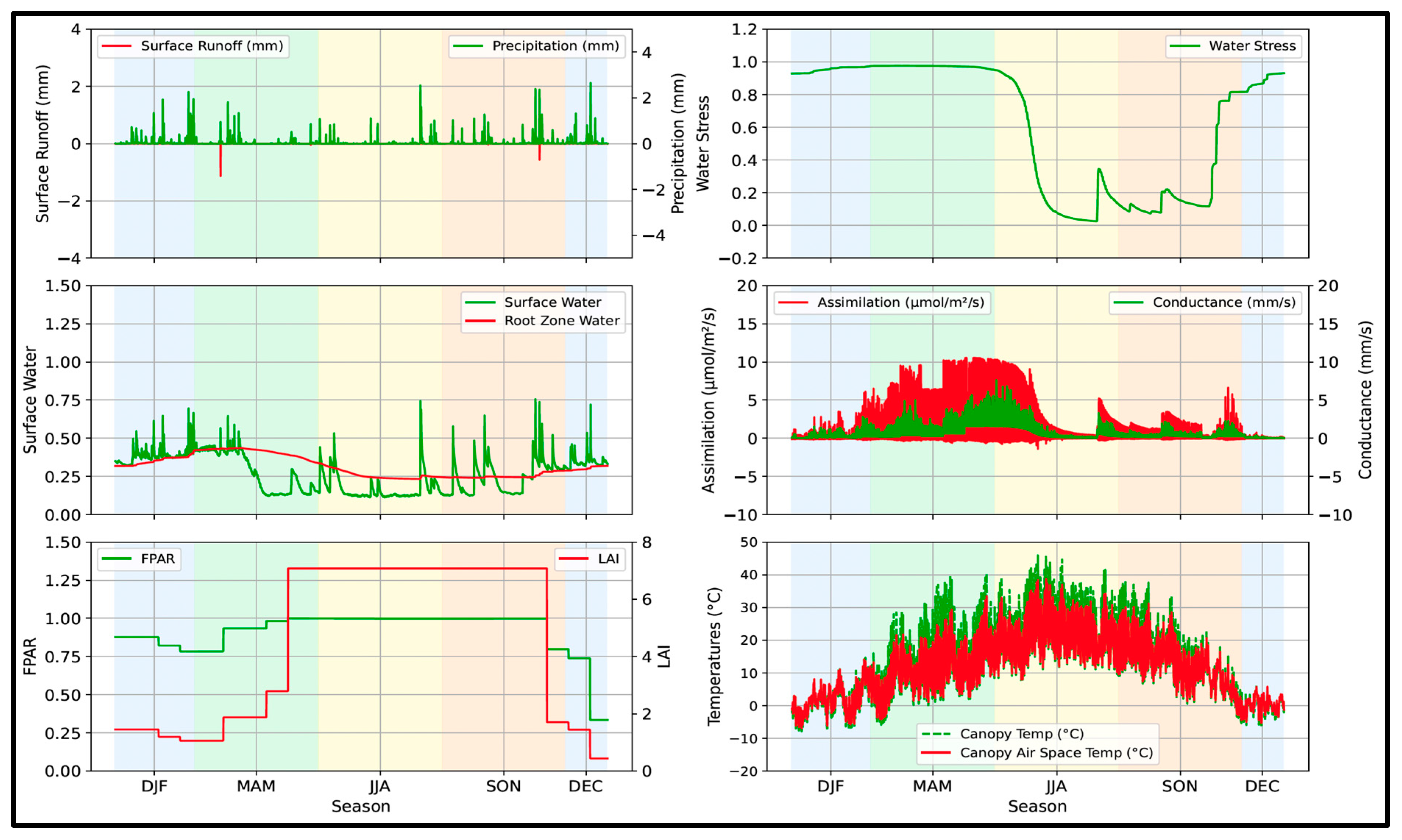

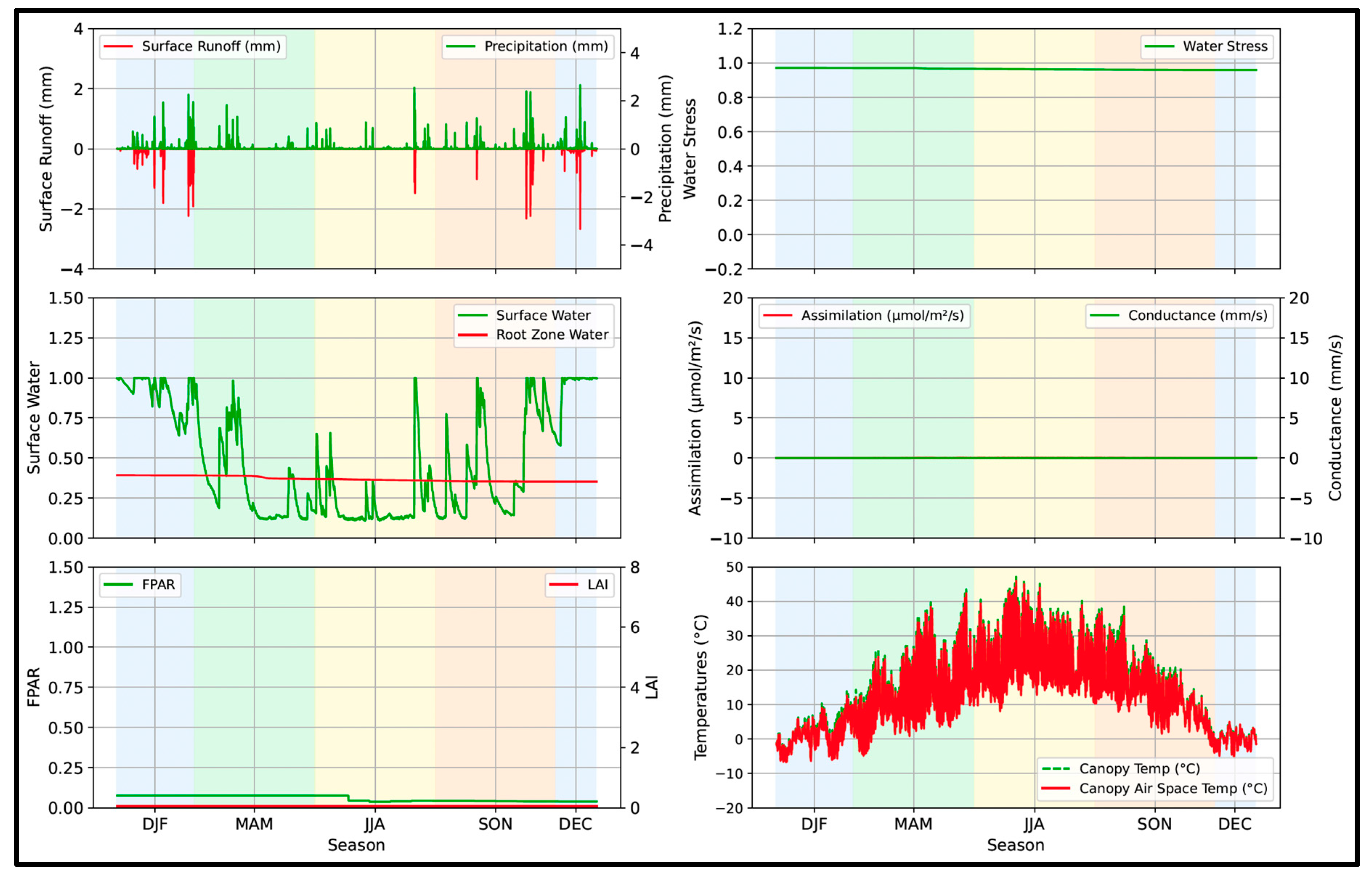

4. Results and Discussion

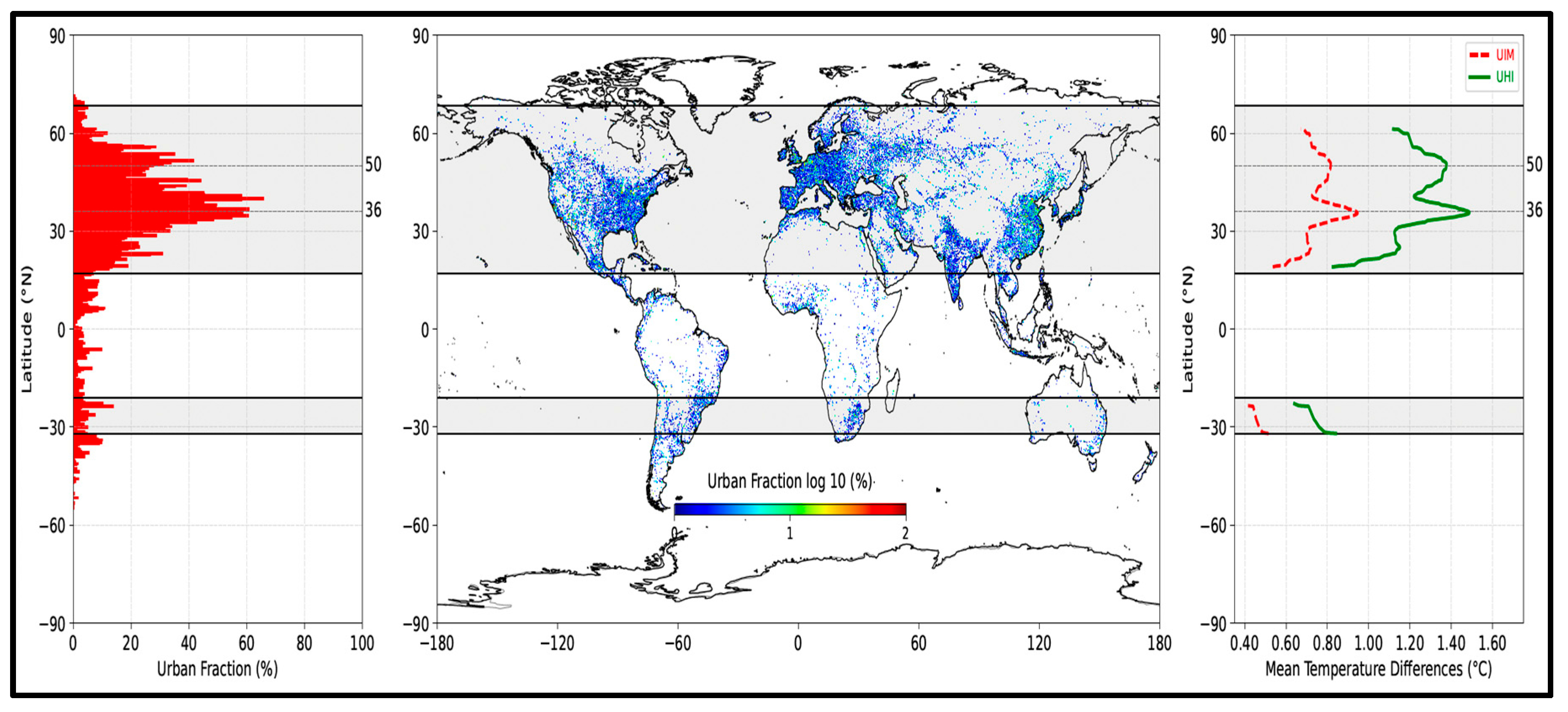

4.1. ISA Distribution

4.2. Hourly Analysis

4.3. Urban Effects on Surface Climate: Insights from UIM and UHI

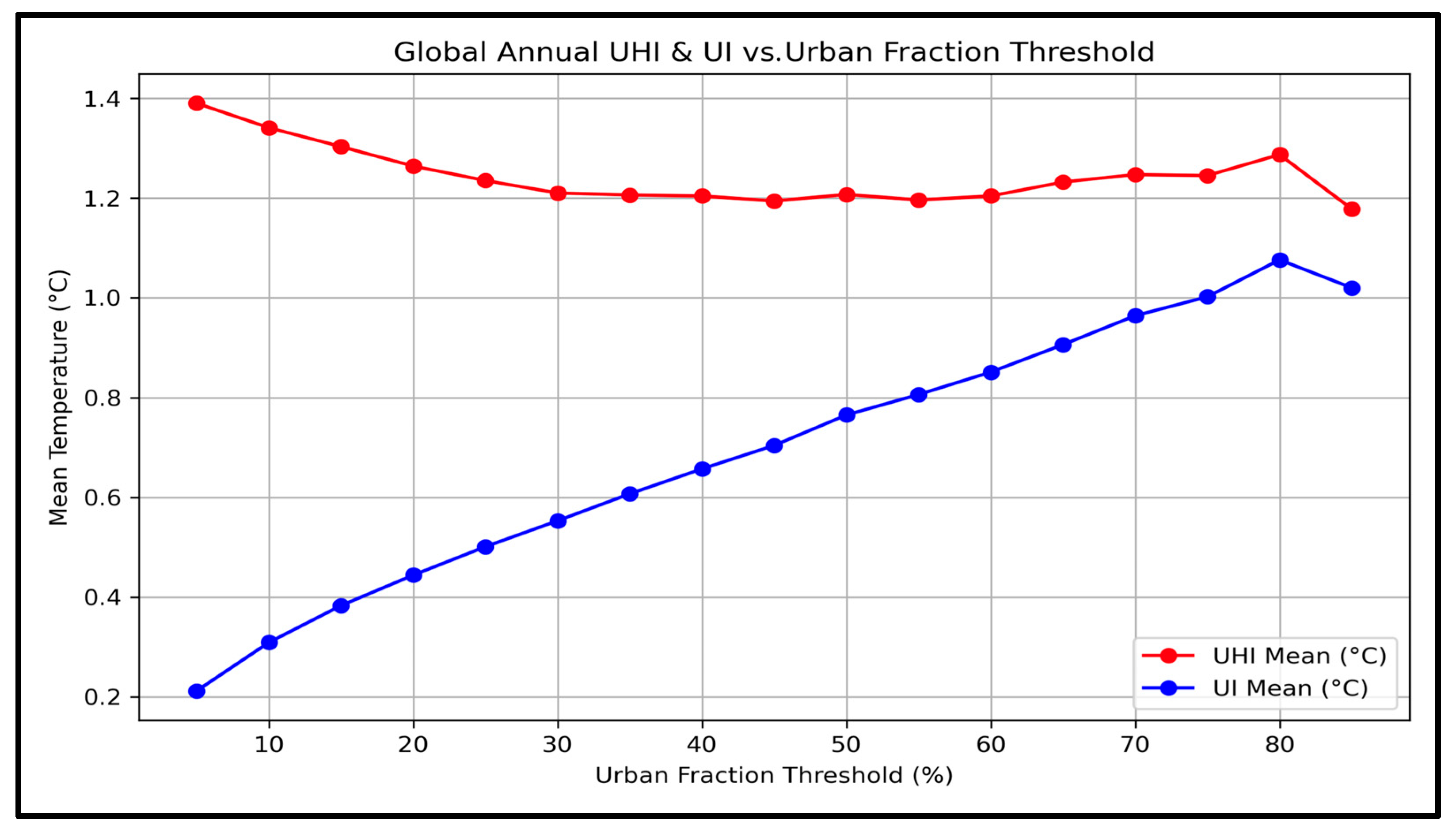

4.3.1. The Urban Heat Island-UHI

4.3.2. The Urban Impact Metric–UIM

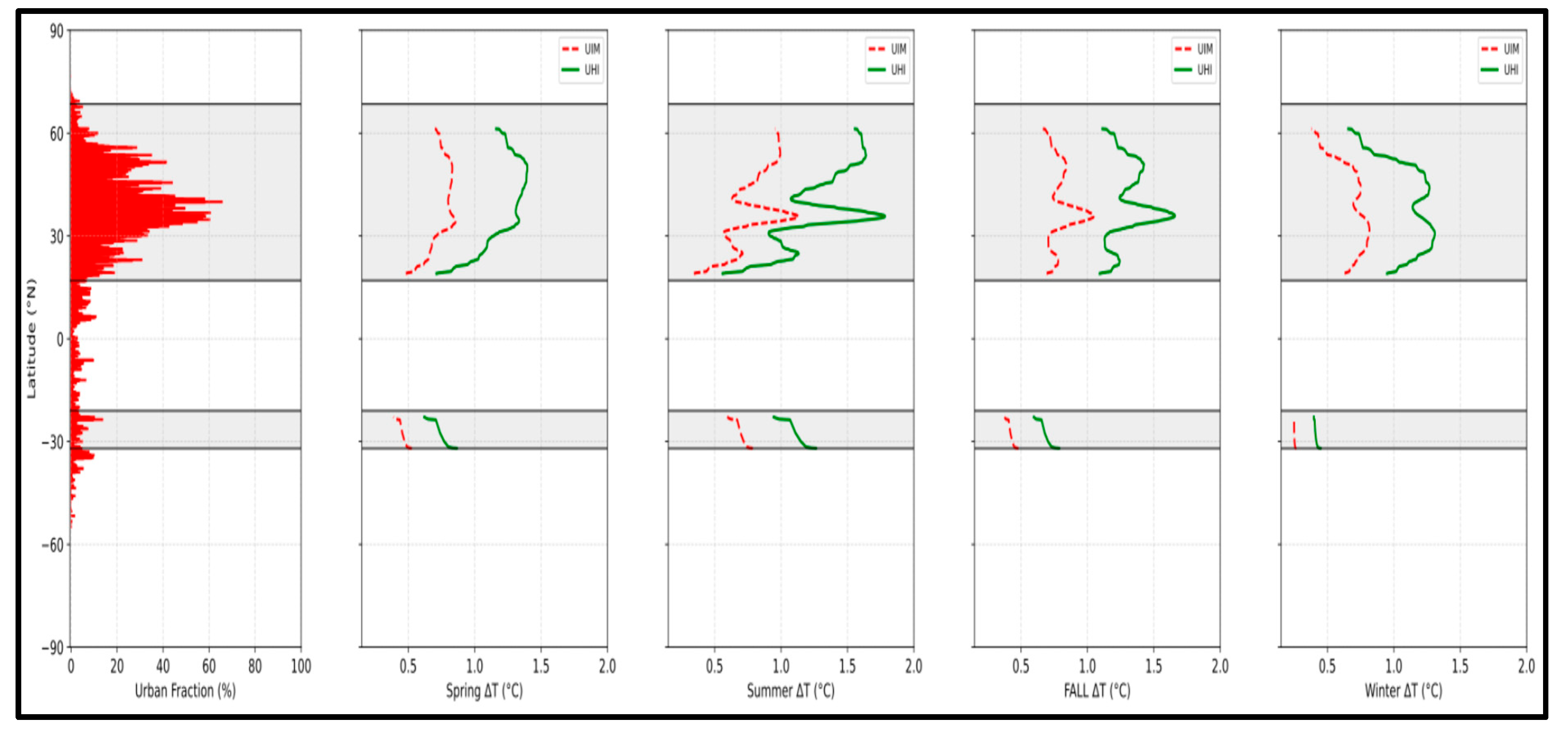

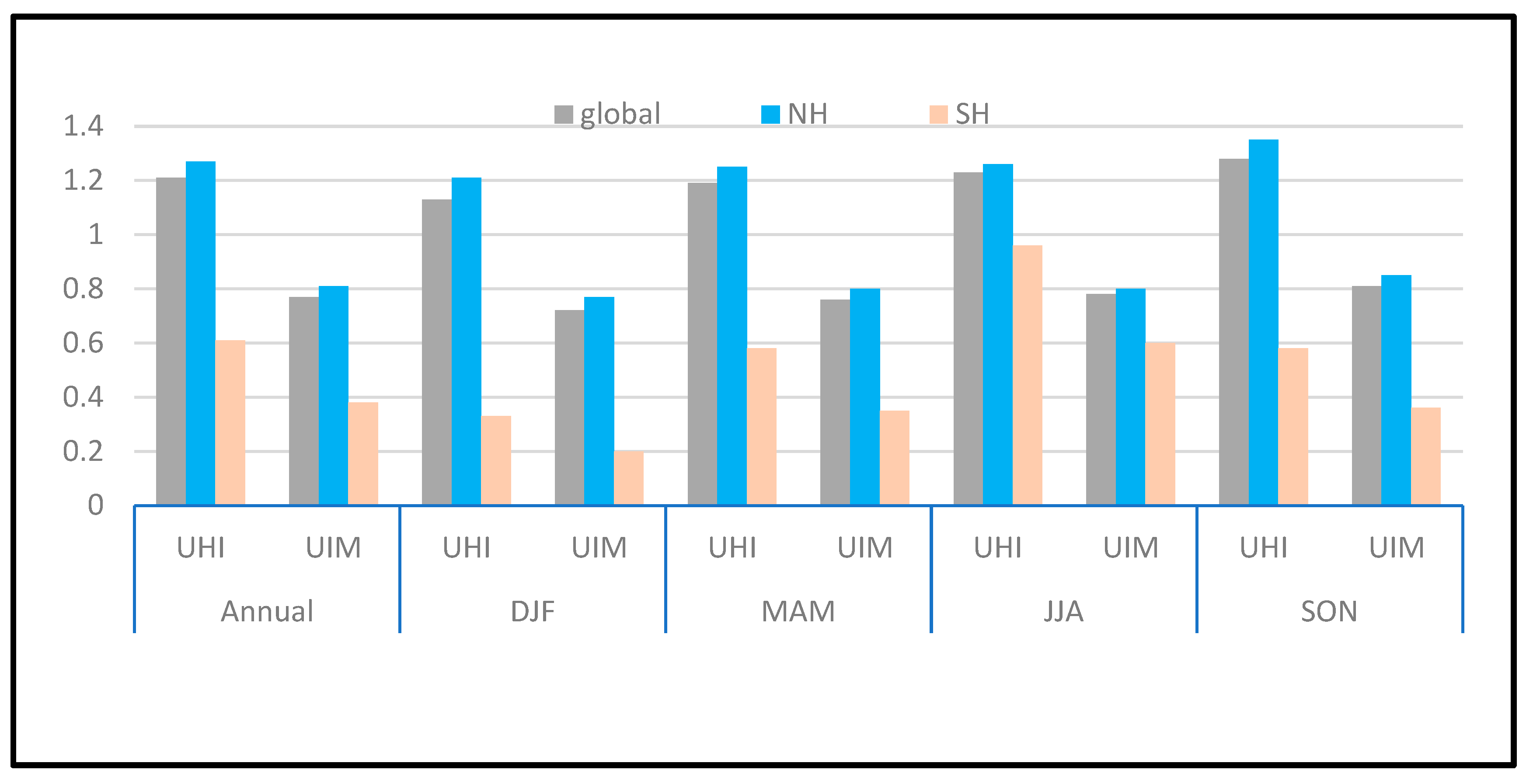

4.4. Seasonal UHI and UIM

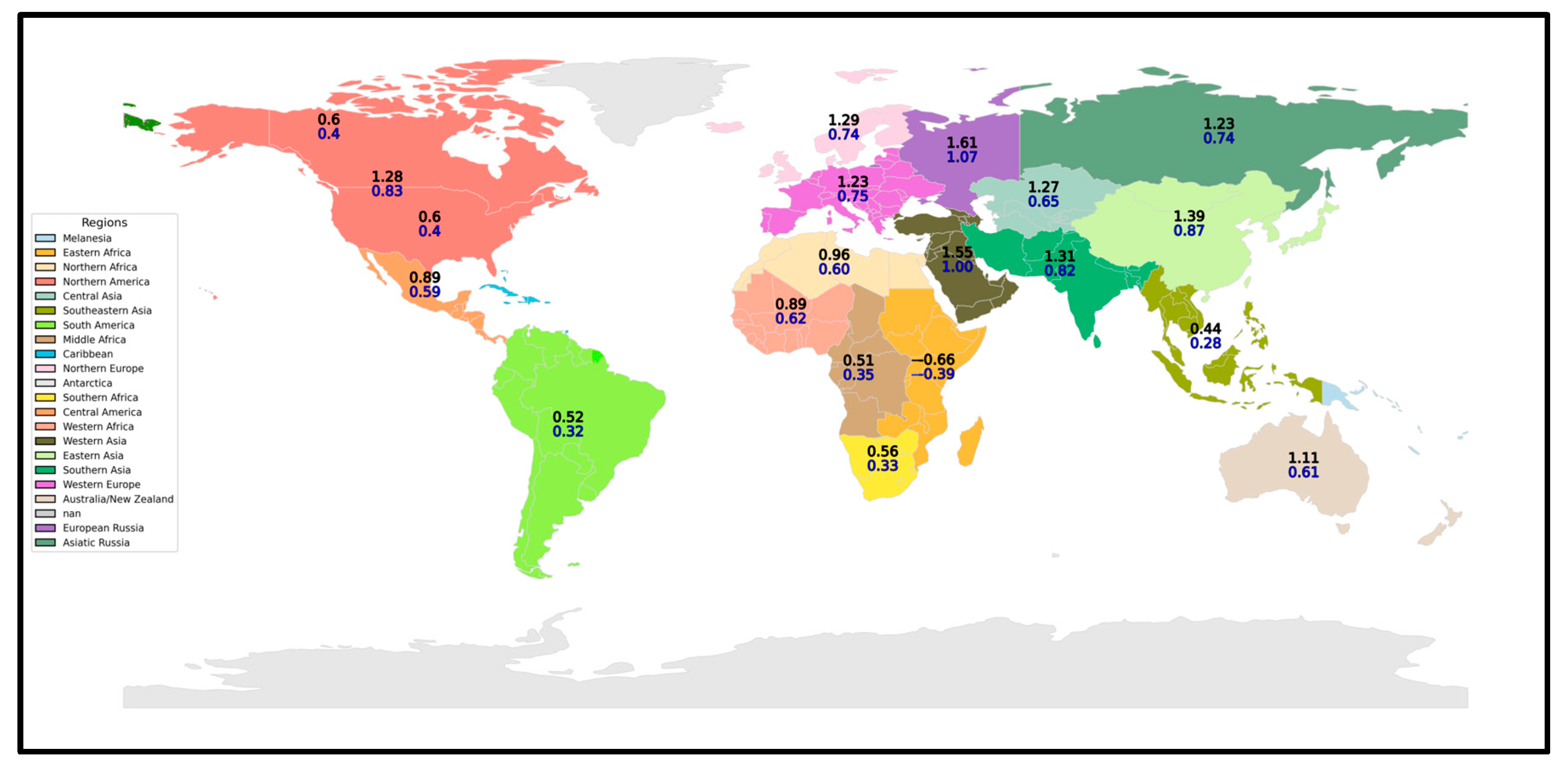

4.5. Regional and Global Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision. UN DESA: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://population.un.org/wup (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Güneralp, B.; Zhou, Y.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Gupta, M.; Yu, S.; Patel, P.L.; Fragkias, M.; Li, X.; Seto, K.C. Global scenarios of urban density and its impacts on building energy use through 2050. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8945–8950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oke, T.R. The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1982, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnfield, A.J. Two decades of urban climate research: A review of turbulence, exchanges of energy and water, and the urban heat island. Int. J. Climatol. 2003, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R.; Mills, G.; Voogt, J.A.; Christen, A. Urban Climates; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, I.D.; Oke, T.R. Local Climate Zones for urban temperature studies. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2012, 93, 1879–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, A.; Balzter, H.; Smith, C.; Remedios, J.; Adamu, B.; Sobrino, J.A.; Srivanit, M.; Weng, Q. A Review on Remote Sensing of Urban Heat and Cool Islands. Land 2017, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Xiao, J.; Bonafoni, S.; Berger, C.; Deilami, K.; Zhou, Y.; Frolking, S.; Yao, R.; Qiao, Z.; Sobrino, J.A. Satellite remote sensing of surface urban heat islands: Progress, challenges, and perspectives. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Xian, G.; Auch, R.; Gallo, K.; Zhou, Q. Urban Heat Island and Its Regional Impacts Using Remotely Sensed Thermal Data—A Review of Recent Developments and Methodology. Land 2021, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyari-Sáska, Z.; Horváth, C.; Pop, S.; Croitoru, A.-E. A New Approach for Identification and Analysis of Urban Heat Island Hotspots. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2024, 15, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhao, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, C. Surface urban heat island in China’s 32 major cities: Spatial patterns and drivers. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 152, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Piao, S.; Ciais, P.; Friedlingstein, P.; Ottlé, C.; Bréon, F.-M.; Nan, H.; Zhou, L.; Myneni, R.B. Surface urban heat island across 419 global big cities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, V. A physically-based scheme for the urban energy budget in atmospheric models. Bound.-Layer. Meteorol. 2000, 94, 357–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusaka, H.; Kimura, F. Coupling a single-layer urban canopy model with a simple atmospheric model: Impact on urban heat island simulation for an idealized case. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 2004, 82, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, M.; Morefield, P.E.; Bierwagen, B.G.; Weaver, C.P. Urban adaptation can roll back warming of emerging megapolitan regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2909–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bounoua, L.; Zhang, P.; Mostovoy, G.; Thome, K.J.; Masek, J.G.; Imhoff, M.L.; Shepherd, M.; Quattrochi, D.; Santanello, J.; Silva, J.; et al. Impact of urbanization on US surface climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 084010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown de Colstoun, E.C.; Huang, C.; Wang, P.; Tilton, J.C.; Tan, B.; Phillips, J.; Niemczura, S.; Ling, P.-Y.; Wolfe, R.E. Global Man-Made Impervious Surface (GMIS) Dataset From Landsat; Version 1.00; NASA SEDAC: Palisades, NY, USA, 2017; p. H4P55KKF. [Google Scholar]

- Friedl, M.A.; Sulla-Menashe, D.; Skole, B.; Hook, S.; Dwyer, J.L.; Morisette, A.; Schaaf, C.B. MODIS Collection 5 global land cover: Algorithm refinements and dataset characterization. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didan, K. MOD13A1 MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 500m SIN Grid V006; Version 006; NASA LP DAAC: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounoua, L.; Nigro, J.; Zhang, P.; Thome, K.; Lachir, A. Mapping urbanization in the United States from 2001 to 2011. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 90, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaro, R.; McCarty, W.; Suárez, M.J.; Todling, R.; Molod, A.; Takacs, L.; Randles, C.A.; Darmenov, A.; Bosilovich, M.G.; Reichle, R.; et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 2017, 30, 5419–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, P.; Randall, D.; Collatz, G.; Berry, J.; Field, C.; Dazlich, D.; Zhang, C.; Collelo, G.; Bounoua, L. A revised land surface parameterization (SiB2) for atmospheric GCMs. Part I: Model formulation. J. Clim. 1996, 9, 676–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounoua, L.; Safia, A.; Masek, J.; Peters-Lidard, C.; Imhoff, M.L. Impact of urban growth on surface climate: A case study in Oran, Algeria. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2009, 48, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, P.J.; Mintz, Y.; Sud, Y.C.; Dalcher, A. A Simple Biosphere Model (SiB) for use within general circulation models. J. Atmos. Sci. 1986, 43, 505–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Bounoua, L.; Thome, K.; Wolfe, R.E.; Imhoff, M. Modeling Surface Climate in U.S. Cities Using Simple Biosphere Model SiB2. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2015, 41, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, J. How much of the world’s land has been urbanized, really? A hierarchical framework for avoiding confusion. Landsc. Ecol. 2014, 29, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Wang, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Niu, Z. Interannual variations in surface urban heat island intensity and associated drivers in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 222, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.B.; Longo, K.M.; Andrade, F.M. Spatial and Temporal Variability Patterns of the Urban Heat Island in São Paulo. Environments 2017, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Space Agency (ESA); WorldCover Consortium. WorldCover 10 m 2020 Product. 2021. Available online: https://worldcover2020.esa.int/ (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Pesaresi, M.; Ehrlich, D.; Ferri, S.; Florczyk, A.J.; Freire, S.; Halkia, M.; Julea, A.; Kemper, T.; Soille, P.; Syrris, V. GHS Built-Up Grid, Derived from Landsat, Multitemporal (1975–1990–2000–2014); European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Asrar, G.R.; Imhoff, M.; Li, X. The surface urban heat island response to urban expansion: A panel analysis for the conterminous United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 605–606, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleson, K.W.; Bonan, G.B.; Feddema, J.; Vertenstein, M. An urban parameterization for a global climate model. Part II: Sensitivity to input parameters and the simulated urban heat island in offline simulations. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2008, 47, 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lee, X.; Smith, R.B.; Oleson, K. Strong contributions of local background climate to urban heat islands. Nature 2014, 511, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bands | Urban Area (km2) | % Urban Fraction |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (17.0 N–68.5 N) | 346,481.28 | 85.03 |

| 2 (21.0 S–17.0 N) | 39,031.99 | 9.58 |

| 3 (32.0 S–21.0 S) | 12,601.56 | 3.09 |

| Total | 97.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bounoua, L.; Boukachaba, N.; Serbin, S.P.; Thome, K.J.; Ed-Dahmany, N.; Lachkham, M.A. Beyond the Urban Heat Island: A Global Metric for Urban-Driven Climate Warming. Urban Sci. 2026, 10, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010006

Bounoua L, Boukachaba N, Serbin SP, Thome KJ, Ed-Dahmany N, Lachkham MA. Beyond the Urban Heat Island: A Global Metric for Urban-Driven Climate Warming. Urban Science. 2026; 10(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleBounoua, Lahouari, Niama Boukachaba, Shawn Paul Serbin, Kurtis J. Thome, Noura Ed-Dahmany, and Mohamed Amine Lachkham. 2026. "Beyond the Urban Heat Island: A Global Metric for Urban-Driven Climate Warming" Urban Science 10, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010006

APA StyleBounoua, L., Boukachaba, N., Serbin, S. P., Thome, K. J., Ed-Dahmany, N., & Lachkham, M. A. (2026). Beyond the Urban Heat Island: A Global Metric for Urban-Driven Climate Warming. Urban Science, 10(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010006