Towards a Unified Currency for Landscape Performance Evaluation: A New Zealand Case

Abstract

1. Introduction

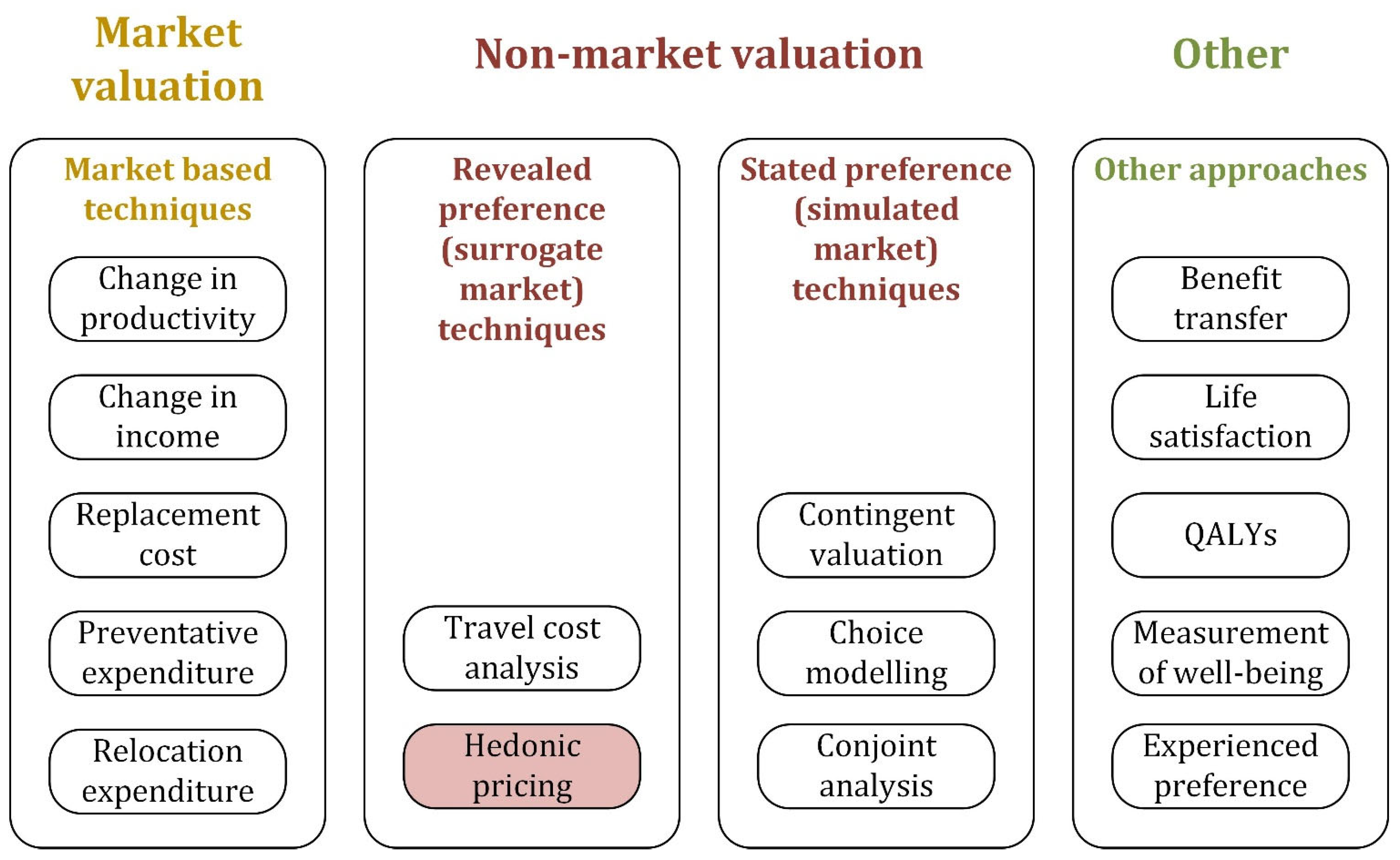

2. Literature

3. Material and Methods

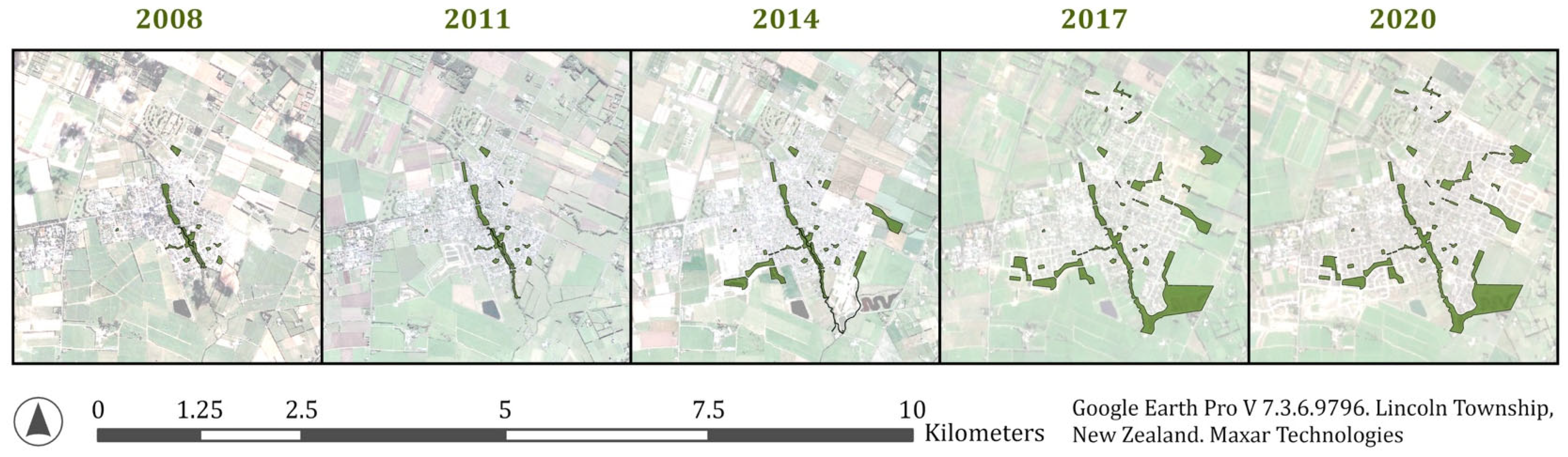

3.1. Study Site

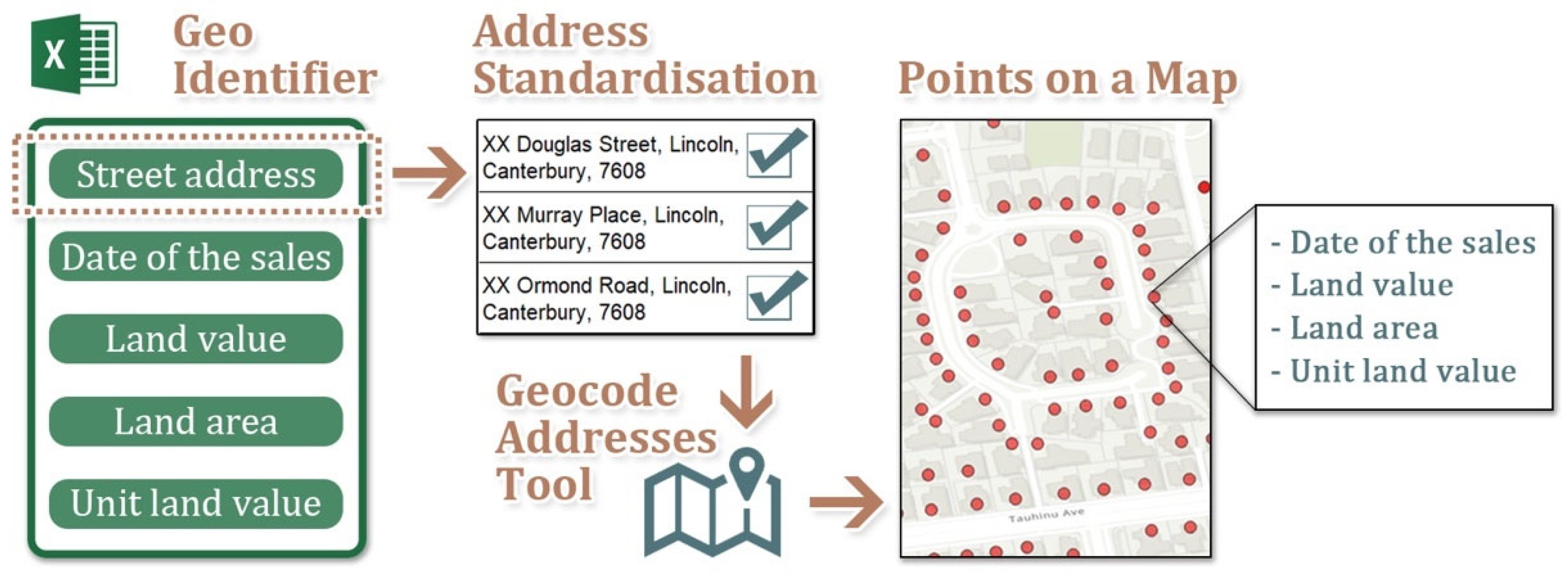

3.2. Data Acquisition and Processing

- A dataset that contains information about all the real estate sales from the past 15 years (from 2007 to 2021) in Lincoln was acquired from Valbiz, Headway Systems [76], a local supplier of New Zealand property sales data. The dataset contains a range of information, including the full street addresses of the property sales, the date of the sales, the value of the sales, rating valuation, including the separate land value and capital value, the floor area of the residential dwellings, and the land area of the properties. These data were cleaned to remove possible non-bona fide sales and unusual data points, including;

- the ones that have a GIS-unidentifiable street address;

- non-residential property sales (e.g., agricultural or commercial lands, by analysing the land size, combining with Google Maps information);

- the sales that have an unreasonably small land size (after double-checking the land sizes with their property registration records);

- the ones that indicate inconsistent land sizes in multiple sales of the same property;

- Suspicious sales (e.g., one-dollar sales or significant “overnight” value fluctuations).

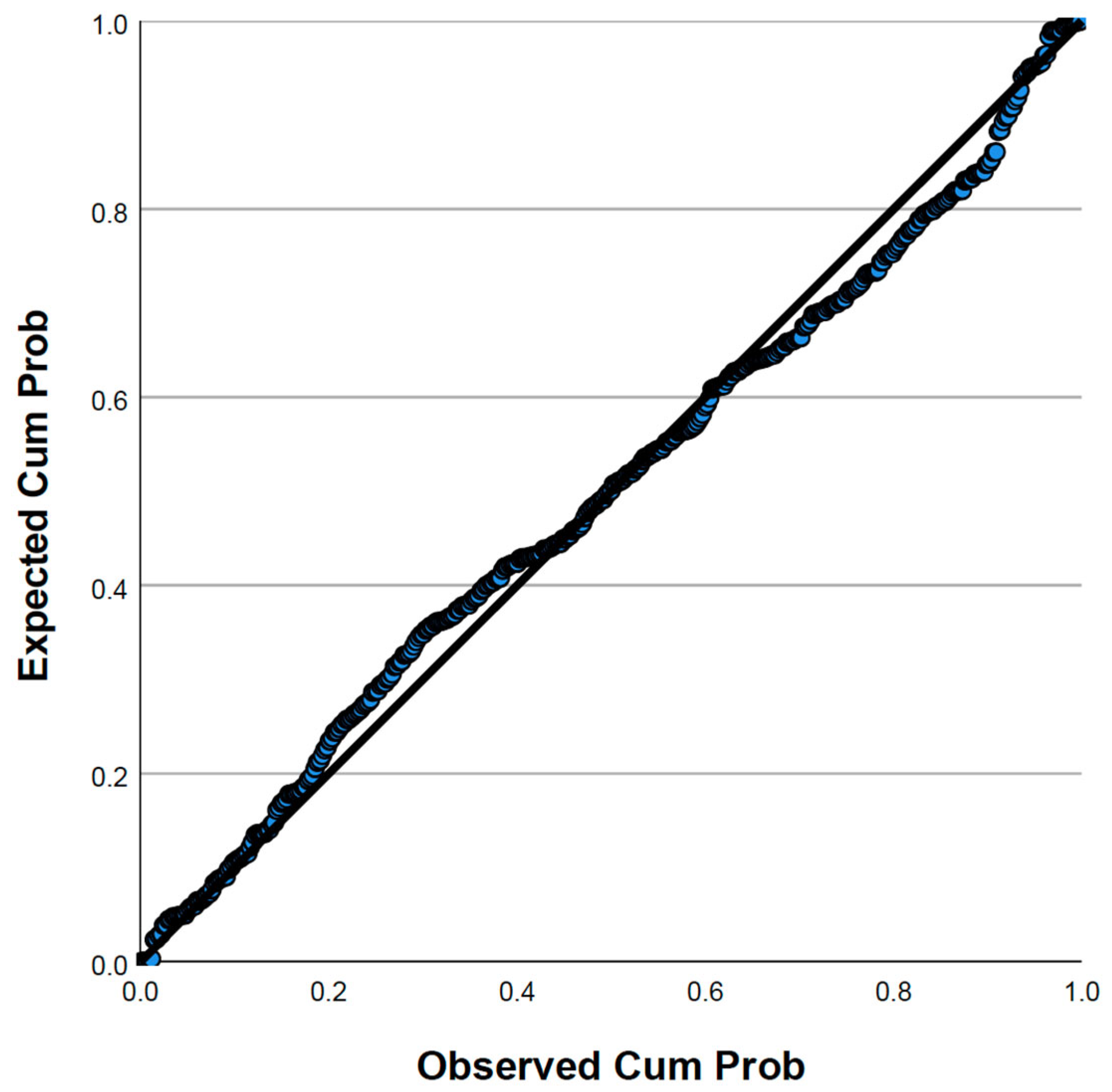

3.3. Model Building

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Static Model

4.2. Temporal Model

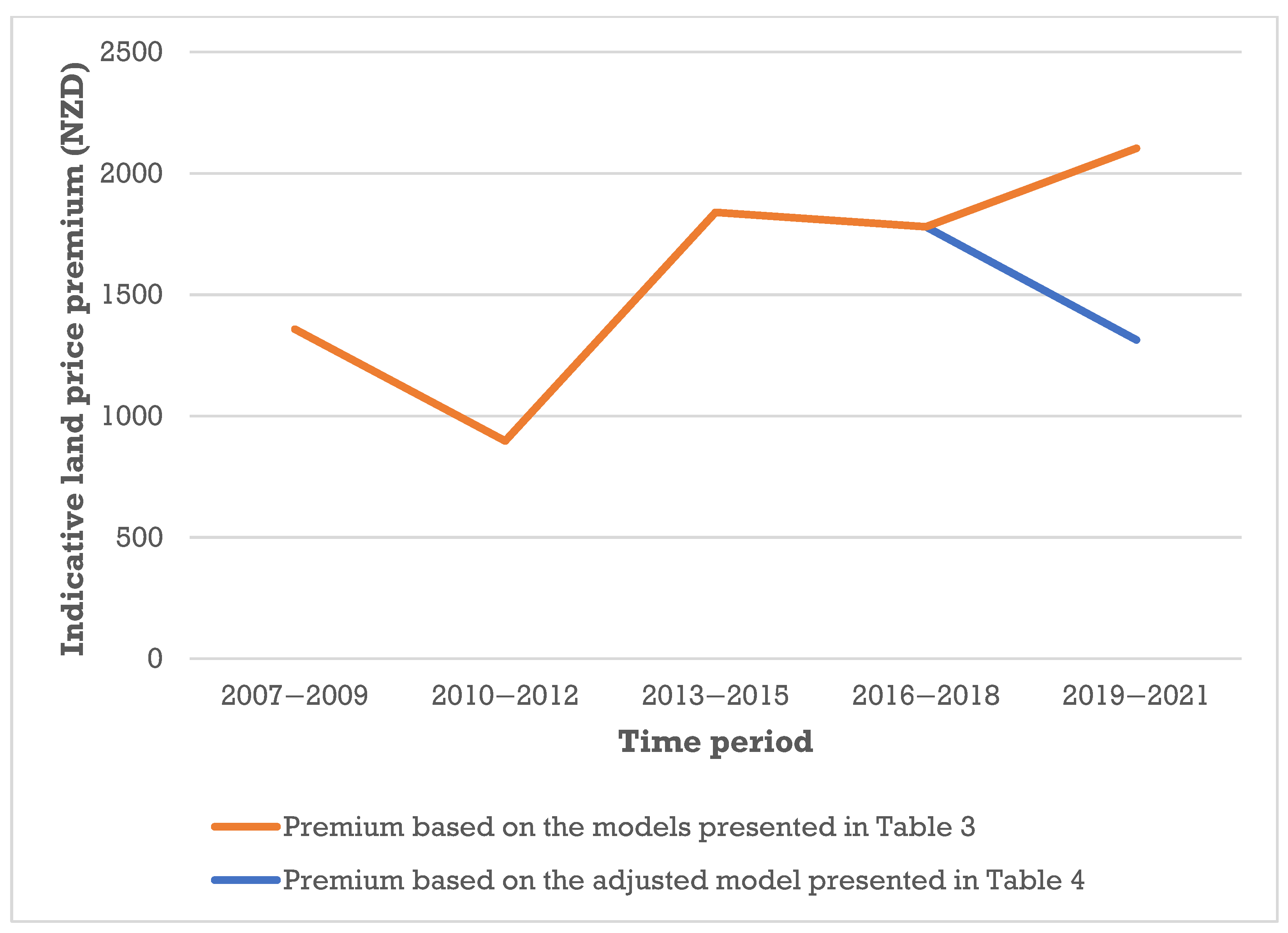

4.3. Measuring the Monetary Value

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBD | Central Business District |

| CSI | Case Study Investigation |

| GISs | Geographical Information Systems |

| LAF | Landscape Architecture Foundation |

| LPE | Landscape Performance Evaluation |

References

- Bell, S.; Sarlöv Herlin, I.; Stiles, R. Exploring the Boundaries of Landscape Architecture; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Egoz, S. Landscape Is More Than the Sum of Its Parts: Teaching an Understanding of Landscape Complexity, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Swaffield, S.; Deming, M.E. Research strategies in landscape architecture: Mapping the terrain. J. Landsc. Archit. 2011, 6, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deming, M.E.; Swaffield, S. Landscape Architecture Research: Inquiry, Strategy, Design; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P.; Thompson, I.; Waterton, E.; Atha, M. The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, I.H. Landscape Architecture: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, M. Evaluating Landscape Performance; Landscape Architecture Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Landscape Architecture Foundation. About Landscape Performance. Available online: https://www.landscapeperformance.org/about-landscape-performance (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Landscape Architecture Foundation. Landscape Performance Series Turns 10. Available online: https://www.landscapeperformance.org/blog/2020/09/landscape-performance-turns-10 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Niland, J. Landscape Architecture Is Now Officially a STEM Discipline. Available online: https://archinect.com/news/article/150356461/landscape-architecture-is-now-officially-a-stem-discipline-according-to-the-u-s-department-of-homeland-security (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Landscape Architecture Foundation. Keeping Promises: Exploring the Role of Post-Occupancy Evaluation in Landscape Architecture. Available online: https://www.landscapeperformance.org/blog/2014/11/role-of-poe (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Chen, G.; Bowring, J.; Davis, S. Measuring the Performance of the Built Environment: An Investigation of Evaluation Methods. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B. Landscape performance evaluation in socio-ecological practice: Current status and prospects. Socio-Ecol. Pract. Res. 2020, 2, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, S.; Binder, C. A research frontier in landscape architecture: Landscape performance and assessment of social benefits. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdil, T.R. Social value of urban landscapes: Performance study lessons from two iconic Texas projects. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2016, 4, 12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Bowring, J.; Davis, S. Performance evaluation: Identifying barriers and enablers for landscape architecture practice. Architecture 2021, 1, 140–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Montis, A. Measuring the performance of planning: The conformance of Italian landscape planning practices with the European Landscape Convention. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 1727–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wende, W. Landscape planning and ecosystem services in Europe and beyond. Ecosyst. People 2019, 15, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkery, L. Connecting Research with Practice to Assess Landscape Performance. Landsc. Rev. 2024, 20, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Bowring, J.; Davis, S. How is “success” defined and evaluated in landscape architecture: A collective case study of landscape architecture performance evaluation approaches in New Zealand. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Bowring, J.; Davis, S. Exploring the terminology, definitions, and forms of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) in landscape architecture. Land 2023, 12, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowring, J.; Chen, G. Te Whāriki Subdivision Phases 1 and 2 methods. In Landscape Performance Series; Landscape Architecture Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Bowring, J. Measuring landscape performance for a subdivision in Canterbury, New Zealand: Reflections and critique of methods. In Proceedings of the CELA 2022 Annual Conference, Evolving Norms: Adapting Scholarship to Disruptive Phenomena, Santa Ana Pueblo, NM, USA, 16–19 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Etter, H.; Schwedes, S.; Hebbrecht, J. Environmental Economics and Ecosystem Valuation—The Rationale Behind; ELD Initiative: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Munns, W.R., Jr.; Rea, A.W. Ecosystem services: Value is in the eye of the beholder. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2015, 11, 332–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannell, D.J.; Roberts, A.M.; Park, G.; Alexander, J. Designing a practical and rigorous framework for comprehensive evaluation and prioritisation of environmental projects. Wildl. Res. 2013, 40, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Bowring, J.; Davis, S. Why landscape architects should embrace landscape performance evaluation—The “market” perspective of landscape development. Landsc. Rev. 2024, 20, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttik, J. The value of trees, water and open space as reflected by house prices in the Netherlands. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 48, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, L. The amenity value of the urban forest: An application of the hedonic pricing method. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1997, 37, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, L.; Terradas, J. Ecological Services of Urban Forest in Barcelona; Institut Municipal de Parcs i Jardins Ajuntament de Barcelona, Àrea de Medi Ambient: Barcelona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, E.G.; Simpson, J.R.; Peper, P.J.; Xiao, Q. Benefit-Cost Analysis of Modesto’s Municipal Urban Forest. Arboric. Urban For. (AUF) 1999, 25, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; McPherson, E.G.; Simpson, J.; Ustin, S. Rainfall Interception by Sacramento’s Urban Forest. Arboric. Urban For. (AUF) 1998, 24, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morancho, A.B. A hedonic valuation of urban green areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 66, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludick, A.; Dyason, D.; Fourie, A. A new affordable housing development and the adjacent housing-market response. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2021, 24, a3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.C.; van Dam, A.A.; Finlayson, C.M.; McInnes, R.J. Worth of wetlands: Revised global monetary values of coastal and inland wetland ecosystem services. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2019, 70, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.A. Better Together? Wetlands, Parks and Housing Prices in Auckland; Auckland Council, Te Kaunihera o Tāmaki Makaurau: Auckland, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.P.; Cromley, R.G.; Banach, K.T. Are Homes Near Water Bodies and Wetlands Worth More or Less? An Analysis of Housing Prices in One Connecticut Town. Growth Change 2015, 46, 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Huang, Z. Spatial and temporal effects of urban wetlands on housing prices: Evidence from Hangzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2018, 73, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapsuwan, S.; Ingram, G.; Burton, M.; Brennan, D. Capitalized amenity value of urban wetlands: A hedonic property price approach to urban wetlands in Perth, Western Australia*. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2009, 53, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Smith, M.D.; Slott, J.M.; Murray, A.B. The value of disappearing beaches: A hedonic pricing model with endogenous beach width. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2011, 61, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, R.; Spencer, G. The Value of an Ocean View: An Example of Hedonic Property Amenity Valuation. Aust. Geogr. Stud. 1998, 36, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.; Crompton, J.L. The contribution of scenic views of, and proximity to, lakes and reservoirs to property values. Lakes Reserv. Sci. Policy Manag. Sustain. Use 2018, 23, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klizentyte, K.; Susaeta, A.; Adams, D.C.; Stein, T.V. Recreation Area Characteristics and Their Impact on Property Values within Florida’s Wekiva River System. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2024, 37, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, S.; Maennig, W. Road noise exposure and residential property prices: Evidence from Hamburg. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2011, 16, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.E.; Herrin, W.E. The Impact of Public School Attributes on Home Sale Prices in California. Growth Change 2000, 31, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, E.G.; Nowak, D.; Heisler, G.; Grimmond, S.; Souch, C.; Grant, R.; Rowntree, R. Quantifying urban forest structure, function, and value: The Chicago Urban Forest Climate Project. Urban Ecosyst. 1997, 1, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, I.S.; McPherson, E.G.; James, R.S. Air Pollutant Uptake by Sacramento’s Urban Forest. Arboric. Urban For. (AUF) 1998, 24, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Hoehn, R.E.; Crane, D.E.; Stevens, J.C.; Walton, J.T. Assessing Urban Forest Effects and Values: Philadelphia’s Urban Forest; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- Zabel, J.E.; Kiel, K.A. Estimating the Demand for Air Quality in Four U.S. Cities. Land Econ. 2000, 76, 174–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.R. Urban forest impacts on regional cooling and heating energy use: Sacramento County case study. J. Arboric. 1998, 24, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolund, P.; Hunhammar, S. Ecosystem services in urban areas. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Crane, D.E. Carbon storage and sequestration by urban trees in the USA. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 116, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Satterfield, T.; Goldstein, J. Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 74, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- de Groot, R.S.; Wilson, M.A.; Boumans, R.M.J. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, J.; Yang, B.; Whitlow, H. Evaluating Landscape Performance—A Guidebook for Metrics and Methods Selection; Landscape Architecture Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Candelaria, J.L.; Sharifi, A.; Simangan, D.; Tabosa, R.M.R. A critical analysis of selected global sustainability assessment frameworks: Toward integrated approaches to peace and sustainability. World Dev. Perspect. 2023, 32, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M. The “Four Spheres” framework for sustainability. Ecol. Complex. 2006, 3, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deming, M.E. Social & cultural metrics: Measuring the intangible benefits of designed landscapes. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 1, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, S.; Mourato, S.; Resende, G.M. The Amenity Value of English Nature: A Hedonic Price Approach. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2014, 57, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Hansz, J.A.; Yang, X. The Pricing Effects of Open Space Amenities. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2016, 52, 244–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba Hernández, R.; Camerin, F. The application of ecosystem assessments in land use planning: A case study for supporting decisions toward ecosystem protection. Futures 2024, 161, 103399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D.J. Selling out on nature. Nature 2006, 443, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, G.N.; Greer, G. New Zealand River Management: Economic Values of Rangitata River Fishery Protection. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2004, 11, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R.T.; Mitchell, R.C.; Hanemann, M.; Kopp, R.J.; Presser, S.; Ruud, P.A. Contingent Valuation and Lost Passive Use: Damages from the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2003, 25, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, R.; Kerr, G.N.; Tipler, C.; Cullen, R.; Ferguson, T. Recreational Water Quality Standards for the Waimakariri River. Report to Canterbury Regional Council; AERU, Lincoln University: Lincoln, New Zealand, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- New Zealand Transport Agency Waka Kotahi. Monetised Benefits and Costs Manual; New Zealand Transport Agency: Wellington, New Zealand, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Transport (MoT). Social Cost of Road Crashes and Injuries; Ministry of Transport: Wellington, New Zealand, 2017.

- Clough, P.; Bealing, M. What’s the Use of Non-Use Values? Non-Use Values and the Investment Statement; NZ Institute of Economic Research: Wellington, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, K.J. Introduction to Revealed Preference Methods. In A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation; Champ, P.A., Boyle, K.J., Brown, T.C., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Bockstael, N.E.; McConnell, K.E. Environmental and Resource Valuation with Revealed Preferences: A Theoretical Guide to Empirical Models; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Montero, J.-M.; Fernández-Avilés, G. Hedonic Price Model. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 2834–2837. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, L.O. The hedonic method. In A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation; Champ, P.A., Boyle, K.J., Brown, T.C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 331–393. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R.; Ruting, B. Environmental Policy Analysis: A Guide to Non-Market Valuation; Productivity Commission Staff Working Paper; Productivity Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics New Zealand. Subnational Population Estimates (RC, SA2), by Age and Sex, at 30 June 1996–2023 (2023 Boundaries); Statistics New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Headway Systems. Headway Systems: Bringing Value to the Property Industry. Available online: https://headway.co.nz/valbiz-v8/ (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Acharya, A.; Basu, S.; Hanink, D.M. Spatial Hedonic Regression Analysis of the Impact of Cell Towers on Las Vegas Real Estate Market. Prof. Geogr. 2022, 74, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Delmelle, E.; Duncan, M. The impact of a new light rail system on single-family property values in Charlotte, North Carolina. J. Transp. Land Use 2012, 5, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.; Anwar, M.M.; Dawood, M. The impact of neighborhood services on land values: An estimation through the hedonic pricing model. GeoJournal 2021, 86, 1915–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiwanka, A.; Wickramaarachchi, N. Critical Determinants of Residential Land Values in a Suburban Area: A Perception Analysis. Sri Lankan J. Real Estate 2022, 1, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbich, M.; Brunauer, W.; Vaz, E.; Nijkamp, P. Spatial heterogeneity in hedonic house price models: The case of Austria. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 390–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottensmann, J.R.; Payton, S.; Man, J. Urban location and housing prices within a hedonic model. J. Reg. Anal. Policy 2008, 38, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L.; Nicholls, S. Impact on property values of distance to parks and open spaces: An update of U.S. studies in the new millennium. J. Leis. Res. 2020, 51, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.; Kweon, B.-S. The Economic Effect of Parks and Community-Managed Open Spaces on Residential House Prices in Baltimore, MD. Land 2025, 14, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, N. Effect of distance to schooling on home prices. Rev. Reg. Stud. 2015, 45, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, W.D. Understanding Regression Assumptions; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Beck, C.; Lewis-Beck, M. Applied Regression: An Introduction; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, J. Applied Linear Regression, 4th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, S.H.; Becker, J.S.; Johnston, D.M.; Rossiter, K.P. An overview of the impacts of the 2010-2011 Canterbury earthquakes. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 14, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyason, D. Disasters and investment: Assessing the performance of the underlying economy following a large-scale stimulus in the built environment. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority. Land Zoning Policy and the Residential Red Zone: Responding to Land Damage and Risk to Life; Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority: Wellington, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brunsdon, N. Christchurch Goes Up and Out. Available online: https://www.buildmagazine.org.nz/assets/PDF/Build-172-73-Feature-Canterbury-Today-Christchurch-Goes-Up-And-Out.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Hodkinson, C. ‘Fear of Missing Out’ (FOMO) marketing appeals: A conceptual model. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, C.Y. Why House Prices Increase in the COVID-19 Recession: A Five-Country Empirical Study on the Real Interest Rate Hypothesis. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, M.; Nahavandi, A. How Does Monetary Policy Affect the New Zealand Housing Market Through the Credit Channel? Reserve Bank of New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry for the Environment. Understanding the Resource Management (Enabling Housing Supply and Other Matters) Amendment Act 2021: Medium Density Residential Standards—A Guide for Territorial Authorities; Ministry for the Environment: Wellington, New Zealand, 2022.

| Variables | Unit | |

|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | Street address | / |

| Date of the sale | Year-Month-Date | |

| Target variable | Unit land value | New Zealand dollar/sqm |

| Predictor variable | Distance to the closest public open space | Metre |

| Distance to the closest water body | Metre | |

| Distance to the closest playground | Metre | |

| Distance to the closest sports field | Metre | |

| Commuting time to the university campus | Minute | |

| Commuting time to the high school campus | Minute | |

| Commuting time to the closest primary school | Minute | |

| Land area | Square metre |

| Unit Land Price | B | 95% CI for B | SE B | β | R2 | ∆R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||||

| Model | 0.85 | 0.85 *** | |||||

| Constant | 104.62 *** | 95.01 | 114.23 | 4.89 | |||

| Land area_Inverse | 142,064.62 *** | 135,670.73 | 148,458.51 | 3252.07 | 0.89 *** | ||

| Distance to the closest public open space | −36.87 *** | −47.63 | −26.12 | 5.47 | −0.14 *** | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | The Static Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Period | (2007–2009) | (2010–2012) | (2013–2015) | (2016–2018) | (2019–2021) | |

| Model | R2 | 0.85 *** | 0.74 *** | 0.80 *** | 0.85 *** | 0.85 *** |

| ∆R2 | 0.85 *** | 0.73 *** | 0.80 *** | 0.85 *** | 0.85 *** | |

| Constant | B | 121.66 *** | 107.44 *** | 100.50 *** | 105.05 *** | 104.62 *** |

| Land area_Inverse | B | 153,799.66 *** | 149,453.08 *** | 143,968.53 *** | 136,705.59 *** | 142,064.62 *** |

| Distance to the closest public open space | B | −23.81 *** | −15.73 *** | −32.25 *** | −31.20 *** | −36.87 *** |

| Unit Land Price | B | 95% CI for B | SE B | β | R2 | ∆R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||||

| Model | 0.44 | 0.44 *** | |||||

| Constant | 108.15 *** | 83.82 | 132.47 | 12.38 | |||

| Land area_Inverse | 145,079.14 *** | 128,649.62 | 161,508.66 | 8359.56 | 0.63 *** | ||

| Distance to the closest public open space | −23.02 ** | −38.16 | −7.89 | 7.70 | −0.11 ** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, G.; Dyason, D.; Davis, S.; Bowring, J. Towards a Unified Currency for Landscape Performance Evaluation: A New Zealand Case. Urban Sci. 2026, 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010007

Chen G, Dyason D, Davis S, Bowring J. Towards a Unified Currency for Landscape Performance Evaluation: A New Zealand Case. Urban Science. 2026; 10(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Guanyu, David Dyason, Shannon Davis, and Jacky Bowring. 2026. "Towards a Unified Currency for Landscape Performance Evaluation: A New Zealand Case" Urban Science 10, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010007

APA StyleChen, G., Dyason, D., Davis, S., & Bowring, J. (2026). Towards a Unified Currency for Landscape Performance Evaluation: A New Zealand Case. Urban Science, 10(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010007

_Chen.jpg)