Techno-Economic Assessment and FP2O Technical–Economic Resilience Study of Peruvian Starch-Based Magnetized Hydrogels at Large Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Process Description

2.2. Process Simulation and Modeling Assumptions

2.3. Technical–Economic Evaluation

2.4. Technical–Economic Resilience via FP2O Methodology

2.5. Considerations for Technical–Economic Resilience Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Technical–Economic Evaluation Analysis

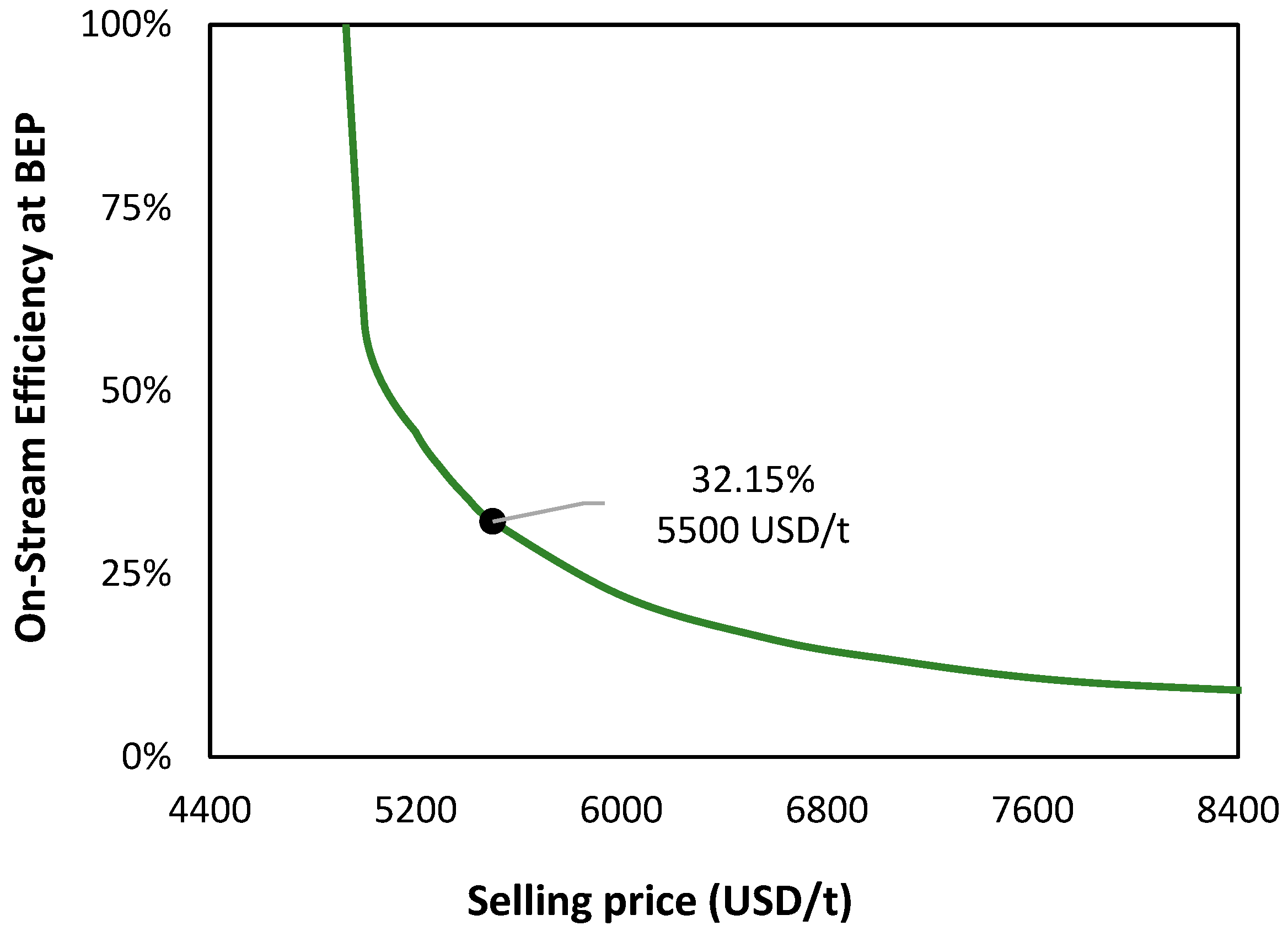

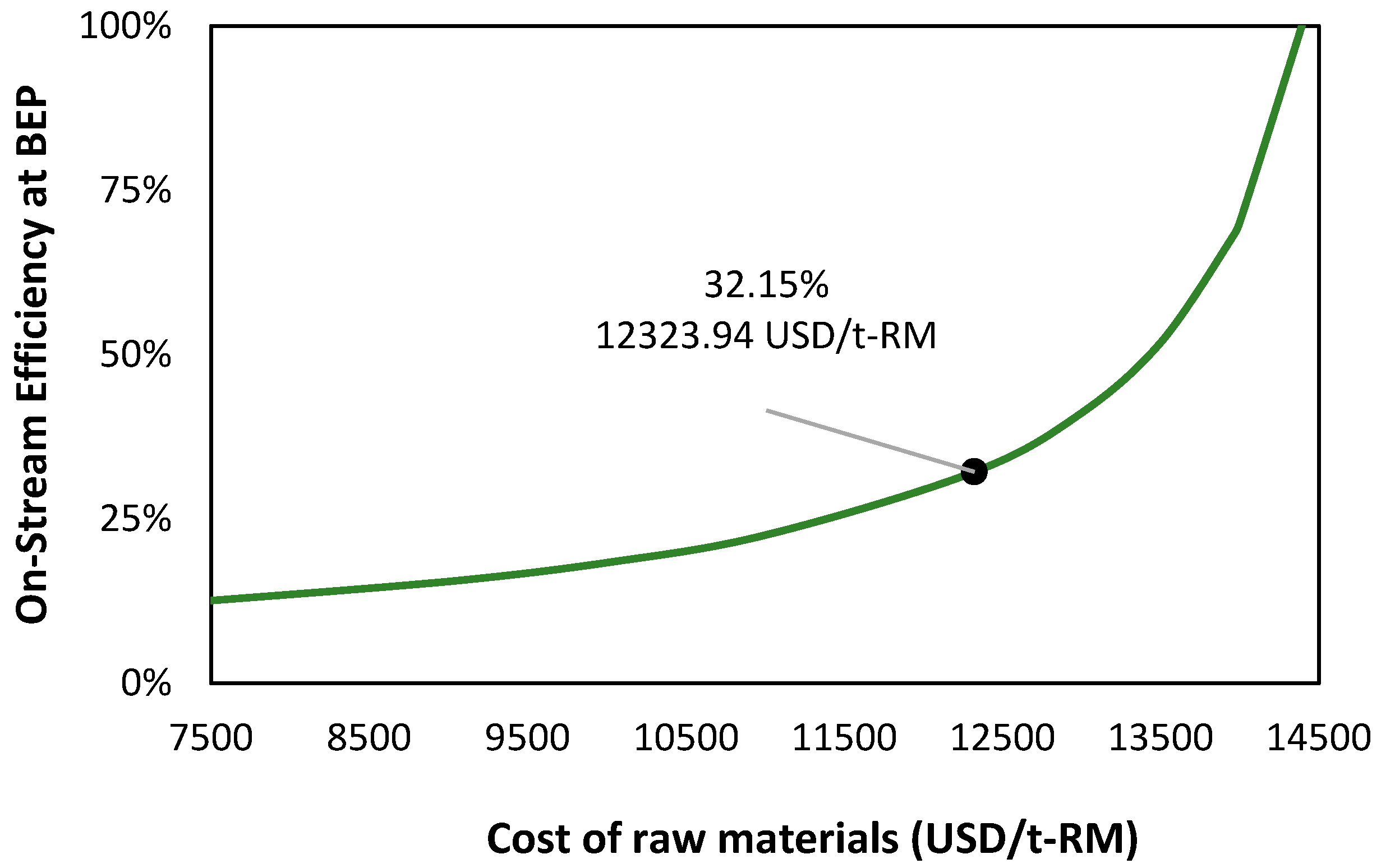

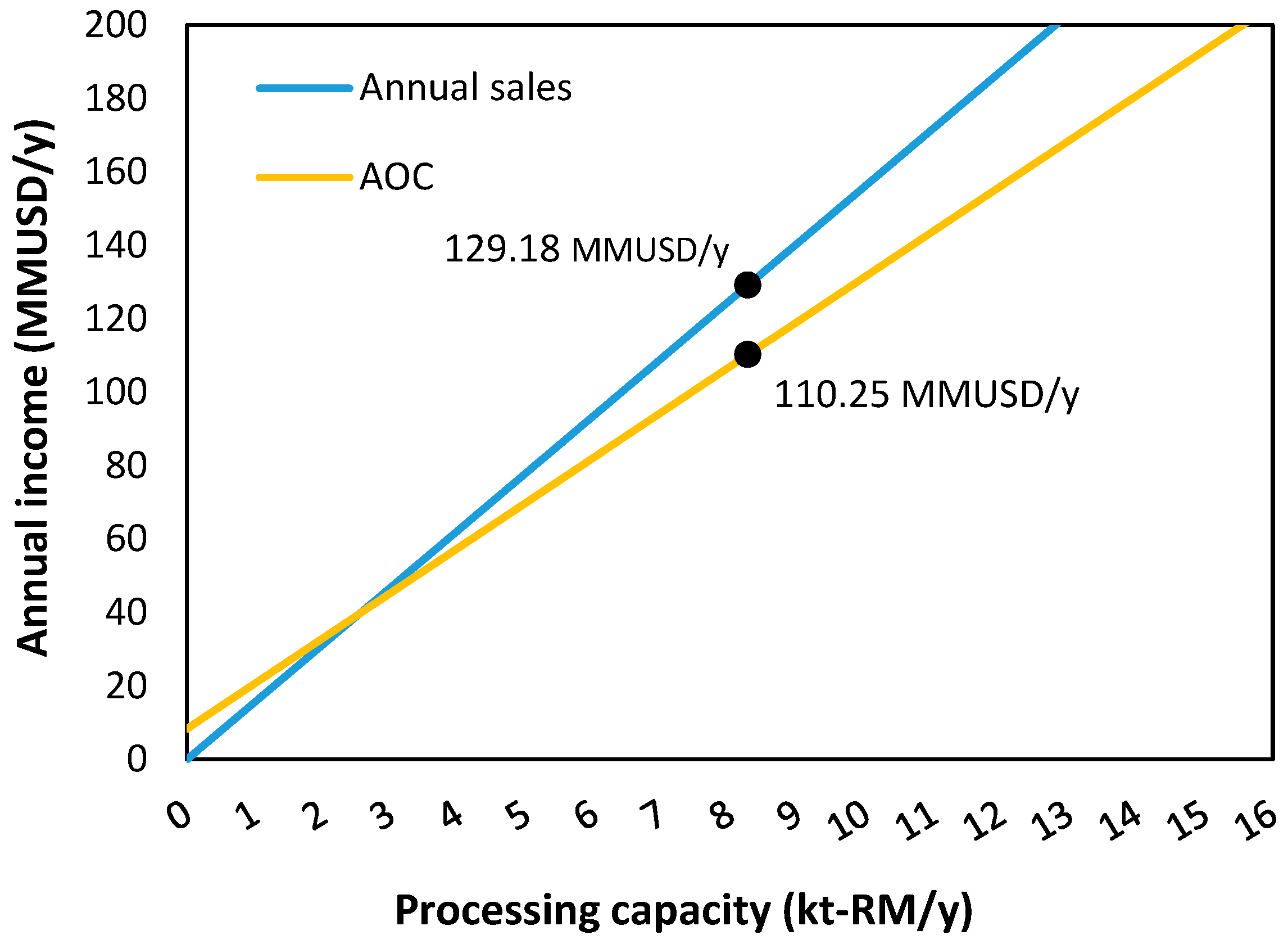

3.2. Break-Even Point Analysis

3.3. FP2O Technical–Economic Resilience Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| AA | Acrylic Acid |

| AR | Amarilla Reyna |

| ACR | Annual Cost/Revenue |

| AFC | Annualized Fixed Costs |

| AOC | Annualized Operating Costs |

| APS | Ammonium Persulfate |

| BEP | Break-Even Point |

| CCF | Cumulative Cash Flow |

| DA | Depreciation and Amortization |

| DFCI | Direct Fixed Capital Investment |

| DGP | Depreciable Gross Profit |

| DPBP | Depreciable Payback Period |

| DPC | Direct Production Costs |

| EBIT | Earnings Before Interest and Taxes |

| EBITDA | Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization |

| EBT | Earnings Before Taxes |

| ECI | Equipment Cost Index |

| EP1 | Economic Potential 1 |

| EP2 | Economic Potential 2 |

| EP3 | Economic Potential 3 |

| FCH | Fixed Charges |

| FCI | Fixed Capital Investment |

| FAOC | Fixed Annual Operating Costs |

| FOB | Free on Board |

| FP2O | Feedstock-Product-Process-Operating |

| GE | General Expenses |

| GP | Gross Profit |

| IFCI | Indirect Fixed Capital Investment |

| IRR | Internal Rate of Return |

| MBA | N, N’-Methylene-Bisacrylamide |

| M&S | Marshall and Swift |

| MR | Maintenance and Repairs |

| MMUSD | Million USD |

| NFCI | Normalized Fixed Capital Investment |

| NPV | Net Present Value |

| NVAOC | Normalized Variable Operating Costs |

| OC | Operating Costs |

| OL | Operating Labor |

| PAA | Polyacrylic Acid |

| PAT | Profitability After Tax |

| PBP | Payback Period |

| POH | Plant Overhead |

| ROI | Return On Investment |

| RM | Raw Material |

| SUC | Start-Up Costs |

| TAC | Total Annual Costs |

| TCI | Total Capital Investment |

| TFC | Total Fixed Costs |

| TMC | Total Manufacturing Cost |

| TPC | Total Product Cost |

| U | Utilities |

| VAOC | Variable Operating Costs |

| WCI | Working Capital Investment |

References

- Mojo-Quisani, A.; Licona-Pacco, K.; Choque-Quispe, D.; Calla-Florez, M.; Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Mamani-Condori, R.; Florez-Huaracha, K.; Huamaní-Melendez, V.J. Physicochemical Properties of Starch of Four Varieties of Native Potatoes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Jia, Y.; Sun, Q.; Yu, M.; Ji, N.; Dai, L.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Xiong, L.; Sun, Q. Recent Advances in the Preparation, Characterization, and Food Application of Starch-Based Hydrogels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 291, 119624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, S.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, J.; Xie, Y.; Cai, L.; Li, M.; Cao, J.; Zhao, H.; Dong, B. A Comparative Analysis of the Water Retention Properties of Hydrogels Prepared from Melon and Orange Peels in Soils. Gels 2025, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshenaj, K.; Ferrari, G. Optimization of Processing Conditions of Starch-Based Hydrogels Produced by High-Pressure Processing (HPP) Using Response Surface Methodology. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1376044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.; Entezami, A.A.; Arami, S.; Rashidi, M.R. Preparation of N-Isopropylacrylamide/Itaconic Acid Magnetic Nanohydrogels by Modified Starch as a Crosslinker for Anticancer Drug Carriers. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2015, 64, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, D.; Oliva, H. Methods for Preparation of Chemical and Physical Hydrogels Based on Starch: A Review. Rev. Latinoam. Metal. Mater. 2012, 32, 154–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A.G.B.; Fajardo, A.R.; Valente, A.J.M.; Rubira, A.F.; Muniz, E.C. Outstanding Features of Starch-Based Hydrogel Nanocomposites. In Starch-Based Blends, Composites and Nanocomposites; Green Chemistry Series; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2015; pp. 236–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Vilcarromero, D.; Pozo, D.; Peña, F.; Manuel Cervantes-Uc, J.; Uribe-Calderon, J.; Velezmoro, C. Characterization of Starches Obtained from Several Native Potato Varieties Grown in Cusco (Peru). J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choque-Quispe, D.; Obregón Gonzales, F.H.; Carranza-Oropeza, M.V.; Solano-Reynoso, A.M.; Ligarda-Samanez, C.A.; Palomino-Ríncón, W.; Choque-Quispe, K.; Torres-Calla, M.J. Physicochemical and Technofunctional Properties of High Andean Native Potato Starch. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 100955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, B.W.; Lazim, A.M. Synthesis and Characterization of Starch-Based Hydrogel by Using Gamma Radiation Technique. Malaysian J. Anal. Sci. 2016, 20, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayati, F.N.; Purnomo, C.W.; Kusumastuti, Y. Rochmadi The Optimization of Hydrogel Strength from Cassava Starch Using Oxidized Sucrose as a Crosslinking Agent. Green Process. Synth. 2023, 12, 20230151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Frank, J.; Liang, J. Structural Features, Physiological Functions and Digestive Properties of Phosphorylated Corn Starch: A Comparative Study of Four Phosphorylating Agents and Two Preparation Methods. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 292, 139146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyniers, S.; De Brier, N.; Matthijs, S.; Brijs, K.; Delcour, J.A. Impact of Mineral Ions on the Release of Starch and Gel Forming Capacity of Potato Flakes in Relation to Water Dynamics and Oil Uptake during the Production of Snacks Made Thereof. Food Res. Int. 2019, 122, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, N.H.; Shameli, K.; Abdullah, E.C.; Abdullah, L.C. A Facile and Green Synthetic Approach toward Fabrication of Starch-Stabilized Magnetite Nanoparticles. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2017, 28, 1590–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunaryono; Taufiq, A.; Munaji; Indarto, B.; Triwikantoro; Zainuri, M.; Darminto. Magneto-Elasticity in Hydrogels Containing Fe3O4 Nanoparticles and Their Potential Applications. AIP Conf. Proc. 2013, 1555, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, V.; Domínguez, H.; Torres, M.D. Formulation and Thermomechanical Characterization of Functional Hydrogels Based on Gluten Free Matrices Enriched with Antioxidant Compounds. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Ruano, M.; Andrés, C.; De, T.; Eduardo, C.; Alzate, O.; Ariel, C.; Alzate, C. Techno-Economic Analysis of Chitosan-Based Hydrogels Production; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gujjala, L.K.S.; Won, W. Process Development, Techno-Economic Analysis and Life-Cycle Assessment for Laccase Catalyzed Synthesis of Lignin Hydrogel. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 364, 128028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MordorIntelligence Mercado de Hidrogel-Tamaño, Informe y Descripción General. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/es/industry-reports/hydrogel-market (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Herrera-Rodríguez, T.C.; Ramos-Olmos, M.; González-Delgado, Á.D. A Joint Economic Evaluation and FP2O Techno-Economic Resilience Approach for Evaluation of Suspension PVC Production. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Maza, S.; González-Delgado, Á.D. Technical–Economic Assessment and FP2O Technical–Economic Resilience Analysis of the Gas Oil Hydrocracking Process at Large Scale. Sci 2025, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Maza, S.; Rojas-Flores, S.; González-Delgado, Á.D. Impact of Mass Integration on the Technoeconomic Performance of the Gas Oil Hydrocracking Process in Latin America. Processes 2025, 13, 3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Dai, R.; Shan, Z.; Chen, H. Fabrication of Starch-Based High-Performance Adsorptive Hydrogels Using a Novel Effective Pretreatment and Adsorption for Cationic Methylene Blue Dye: Behavior and Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peighambardoust, S.J.; Fakhiminajafi, B.; Mohammadzadeh Pakdel, P.; Azimi, H. Simultaneous Elimination of Cationic Dyes from Water Media by Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Graft-Poly(Acrylamide)/Magnetic Biochar Nanocomposite Hydrogel Adsorbent. Environ. Res. 2025, 273, 121150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, S.; Chen, C.C. Thermodynamic Analysis of Hydrogel Swelling in Aqueous Sodium Chloride Solutions. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 348, 118421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, J.L.; Ferro, V.R.; Giroir-Fendler, A. Application of the E-NRTL Model to Electrolytes in Mixed Solvents Methanol-, Ethanol- Water, and PEG-Water. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2022, 560, 113516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.S.; Timmerhaus, K.D. Solutions Manual to Accompany Plant Design and Economics for Chemical Engineers, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hil: Columbus, OH, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- El-Halwagi, M.M. Overview of Process Economics. In Sustainable Design Through Process Integration; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 15–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Aristizábal, R.; Meza-Cuentas, E.; González-Delgado, Á.D. Economic Evaluation and Technoeconomic Resilience Analysis of Two Routes for Hydrogen Production via Indirect Gasification in North Colombia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Halwagi, M.M. A Return on Investment Metric for Incorporating Sustainability in Process Integration and Improvement Projects. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2017, 19, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Halwagi, M.M. Sustainable Design Through Process Integration: Fundamentals and Applications to Industrial Pollution Prevention, Resource Conservation, and Profitability Enhancement; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia_Agraria_de_Noticias Perú Produjo 5.4 Millones de Toneladas de Papa En 2020. Available online: https://agraria.pe/noticias/peru-produjo-5-4-millones-de-toneladas-de-papa-en-2020-23985 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Chauhan, A.; Islam, F.; Imran, A.; Ikram, A.; Zahoor, T.; Khurshid, S.; Shah, M.A. A Review on Waste Valorization, Biotechnological Utilization, and Management of Potato. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5773–5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; McDonald, A.G. Chemical and Thermal Characterization of Potato Peel Waste and Its Fermentation Residue as Potential Resources for Biofuel and Bioproducts Production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 8421–8429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Yan, D.Y.S.; Khan, M.; Zhang, Z.; Lo, I.M.C. Application of Magnetic Hydrogel for Anionic Pollutants Removal from Wastewater with Adsorbent Regeneration and Reuse. J. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste 2016, 21, 04016008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Shen, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, W. Evaluation of Three Suction Pretreatment Systems for the Air Compressor. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 246, 123022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, A.; Shah, A. Techno-Economic Analysis of the Production of Lactic Acid from Lignocellulosic Biomass. Fermentation 2023, 9, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, A.; Pourfayaz, F.; Saifoddin, A. Techno-Economic Assessment and Sensitivity Analysis of Biodiesel Production Intensified through Hydrodynamic Cavitation. Energy Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1997–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbird, D.; Davis, R.; Tao, L.; Kinchin, C.; Hsu, D.; Aden, A.; Schoen, P.; Lukas, J.; Olthof, B.; Worley, M.; et al. Process Design and Economics for Biochemical Conversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Ethanol: Dilute-Acid Pretreatment and Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Corn Stover; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriagada, G.; Ignacio, P. Estudio de Estabilidad En Las Interconexiones Eléctricas Internacionales En Latinoamérica; Facultad de Ciencias Físicas y Matemáticas, Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2021; Available online: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/181814 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Pérez-Ahumada, P.; Carrasco, K. Política de Clases y Confianza En Los Sindicatos En América Latina. Lat. Am. Res. Rev. 2025, 60, 410–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, N.; Han, J. Techno-Economic Analysis of Food Waste Valorization for Integrated Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoates and Biofuels. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 348, 126796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobasu, A.; Quaglietti, L.; Ricci, M. Tracking Global Economic Uncertainty: Implications for the Euro Area. IMF Econ. Rev. 2024, 72, 820–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Ruano, J.A.; Taimbu de la Cruz, C.A.; Orrego Alzate, C.E.; Cardona Alzate, C.A. Techno–Economic Analysis of Chitosan-Based Hydrogels Production. In Cellulose-Based Superabsorbent Hydrogels; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1769–1790. ISBN 978-3-319-77830-3. [Google Scholar]

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Processing capacity (starch, t/year) | 8267 |

| Main product flow (magnetized hydrogel, t/year) | 23,488 |

| Raw material cost (USD/t) | 12,323.94 |

| Main product selling price (USD/t) | 5500 |

| Plant life (years) | 15 |

| Salvage value | 10% of the depreciable FCI |

| Construction time | 2 years |

| Location | Peru |

| Tax rate | 30% |

| Discount rate | 12% |

| Capacity operated | 50% in the 1st year, 70% in the 2nd year, 100% from the 3rd year onwards |

| Subsidies (USD/year) | 0 |

| Process type | New and untested process |

| Process control | Digital |

| Type of project | Plant on undeveloped land |

| Type of soil | Soft clay |

| Contingency percentage (%) | 20 |

| Tank design code | ASME |

| Vessel diameter specification | Inner diameter |

| Operator hour cost (USD/h) | 30 |

| Supervisor hourly cost (USD/h) | 35 |

| Salaries per year | 13 |

| Utilities | Gas, water, vapor, and electricity |

| Process fluids | Solid-liquid-gas |

| Depreciation method | Linear for 15 years |

| Annualized Operating Costs (AOC) | Total (USD/Year) |

|---|---|

| Variable Annual Operating Cost (VAOC) | |

| Raw materials (RM) | 101,886,288.39 |

| Utilities (U) | 1,708,102.61 |

| Total VAOC | 103,594,391.00 |

| Normalized Variable Annual Operating Cost (NVAOC) | 12,530.55 |

| Fixed Annual Operating Cost (FAOC) | |

| Local taxes | 786,053.70 |

| Insurance | 262,017.90 |

| Interest/rent | 497,834.01 |

| Fixed charges (FCH) | 1,545,905.61 |

| Maintenance and repairs (MR) | 1,310,089.49 |

| Operating supplies | 196,513.42 |

| Operating labor (OL) | 1,252,533.33 |

| Direct supervision and clerical labor | 187,880.00 |

| Laboratory charges | 12,253.33 |

| Patents and royalties | 262,017.90 |

| Direct production cost (DPC) | 3,334,287.47 |

| Plant overhead (POH) | 751,520.00 |

| Total Manufacturing Cost (TMC) | 4,085,807.48 |

| Saling administration and General expenses (GE) | 1,021,451.87 |

| Total FAOC | 6,653,164.95 |

| Annualized Operating Costs (AOC) | 110,247,555.95 |

| Capital Costs | Total |

|---|---|

| Equipment cost F.O.B. (USD) | 4,335,145 |

| Delivered purchased equipment cost (USD) | 5,202,174 |

| Purchased equipment (installed; USD) | 1,560,652 |

| Instrumentation (installed; USD) | 624,261 |

| Piping (installed; USD) | 1,560,652 |

| Electrical network (installed; USD) | 988,414 |

| Buildings (including services; USD) | 2,601,087 |

| Services facilities (installed; USD) | 2,080,870 |

| Total DFCI (USD) | 14,618,109 |

| Land (USD) | 312,130 |

| Land improvements (USD) | 2,080,870 |

| Engineering and supervision (USD) | 2,705,130 |

| Equipment (research & development; USD) | 520,217 |

| Construction costs (USD) | 1,768,739 |

| Legal expenses (USD) | 52,021.2 |

| Contractors’ fees (USD) | 1,023,268 |

| Contingency (USD) | 3,121,304 |

| Total IFCI (USD) | 11,583,680 |

| Fixed capital investment (FCI; USD) | 26,201,790 |

| Working capital (WCI; USD) | 20,961,32 |

| Start-up (SUC; USD) | 2,620,179 |

| Total capital investment (TCI; USD) | 49,783,401 |

| Salvage value FCI (USD) | 2,588,966 |

| Annualized fixed costs (AFC; USD/year) | 1,574,188 |

| Total Annualized Costs (TAC) | 111,821,744.21 |

| Total Fixed Costs (TFC) | 8,227,353.21 |

| Indicator | Total |

|---|---|

| Gross profit (depreciation not included) (GP; USD) | 18,935,344.05 |

| Gross profit (depreciation included) (DGP; USD) | 17,361,155.79 |

| Profitability after tax (PAT; USD) | 12,152,809.05 |

| Economic potentials 1 (EP1; USD/year) | 27,296,611.61 |

| Economic potentials 2 (EP2; USD/year) | 25,588,509.00 |

| Economic potentials 3 (EP3; USD/year) | 18,935,344.05 |

| Cumulative cash flow (CCF; 1/year) | 0.38 |

| Payback period (PBP; years) | 2.13 |

| Depreciable payback period (DPBP; years) | 5.80 |

| Return on investment (% ROI) | 24.41 |

| Net present value (NPV; MMUSD) 1 | 25.38 |

| Annual cost/revenue (ACR) | 3.73 |

| Internal rate of return (% IRR) | 34.52 |

| Indicator | Total |

|---|---|

| Earnings before taxes (EBT; USD) | 18,437,510.04 |

| Earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT ≡ EP3; USD) | 18,935,344.05 |

| Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA; USD) | 20,509,532.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alviz-Meza, A.; Carranza-Oropeza, M.V.; González-Delgado, Á.D. Techno-Economic Assessment and FP2O Technical–Economic Resilience Study of Peruvian Starch-Based Magnetized Hydrogels at Large Scale. Sci 2025, 7, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040181

Alviz-Meza A, Carranza-Oropeza MV, González-Delgado ÁD. Techno-Economic Assessment and FP2O Technical–Economic Resilience Study of Peruvian Starch-Based Magnetized Hydrogels at Large Scale. Sci. 2025; 7(4):181. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040181

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlviz-Meza, Anibal, María Verónica Carranza-Oropeza, and Ángel Darío González-Delgado. 2025. "Techno-Economic Assessment and FP2O Technical–Economic Resilience Study of Peruvian Starch-Based Magnetized Hydrogels at Large Scale" Sci 7, no. 4: 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040181

APA StyleAlviz-Meza, A., Carranza-Oropeza, M. V., & González-Delgado, Á. D. (2025). Techno-Economic Assessment and FP2O Technical–Economic Resilience Study of Peruvian Starch-Based Magnetized Hydrogels at Large Scale. Sci, 7(4), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040181