Development of an Autonomous and Interactive Robot Guide for Industrial Museum Environments Using IoT and AI Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. State of the Art

1.1.1. Localization and Mapping

1.1.2. Path Planning

1.1.3. Obstacle Avoidance

1.1.4. LLM in Robotics

1.1.5. Comercial Robots

2. Materials and Methods

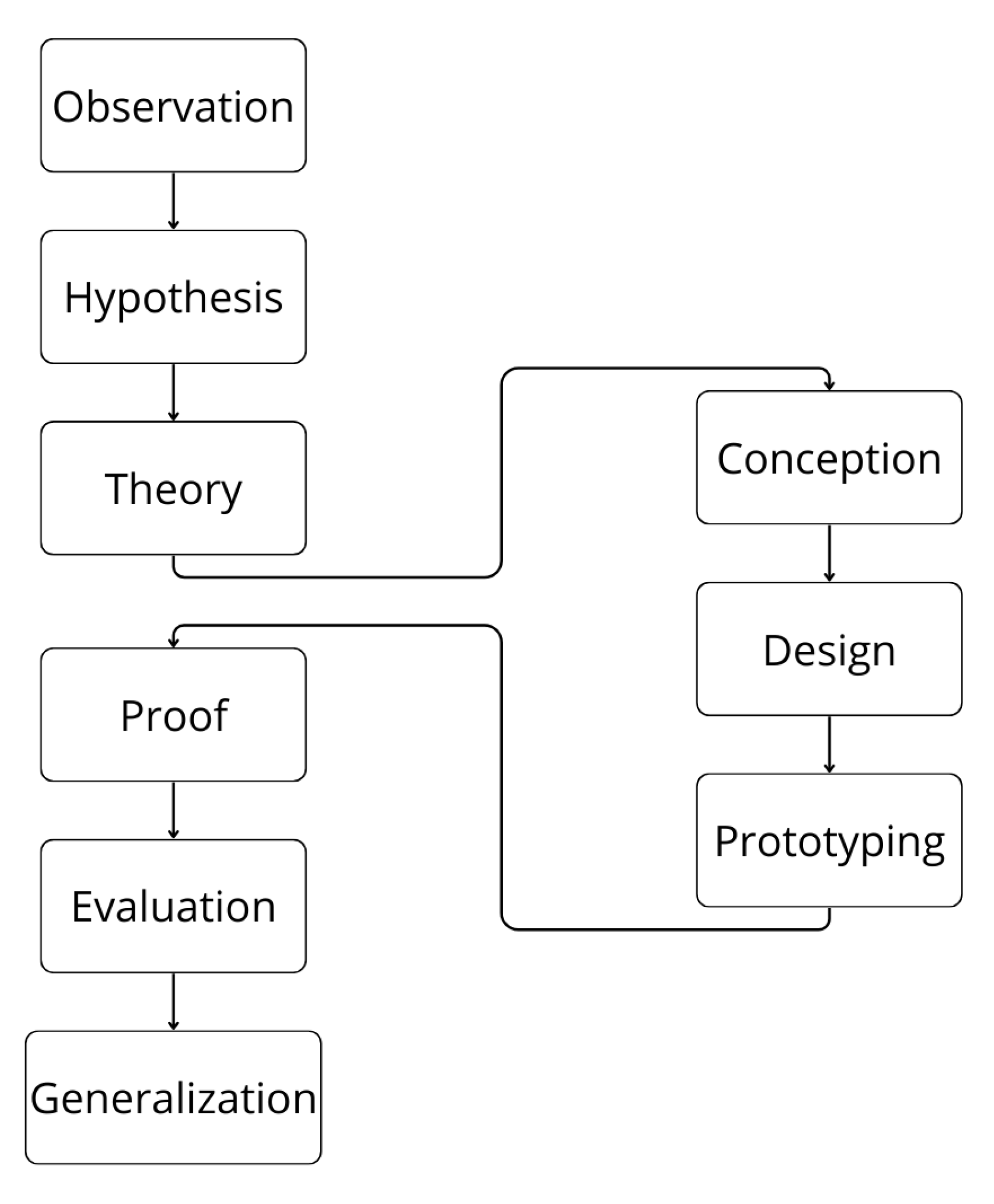

2.1. Design Inclusive Research (DIR)

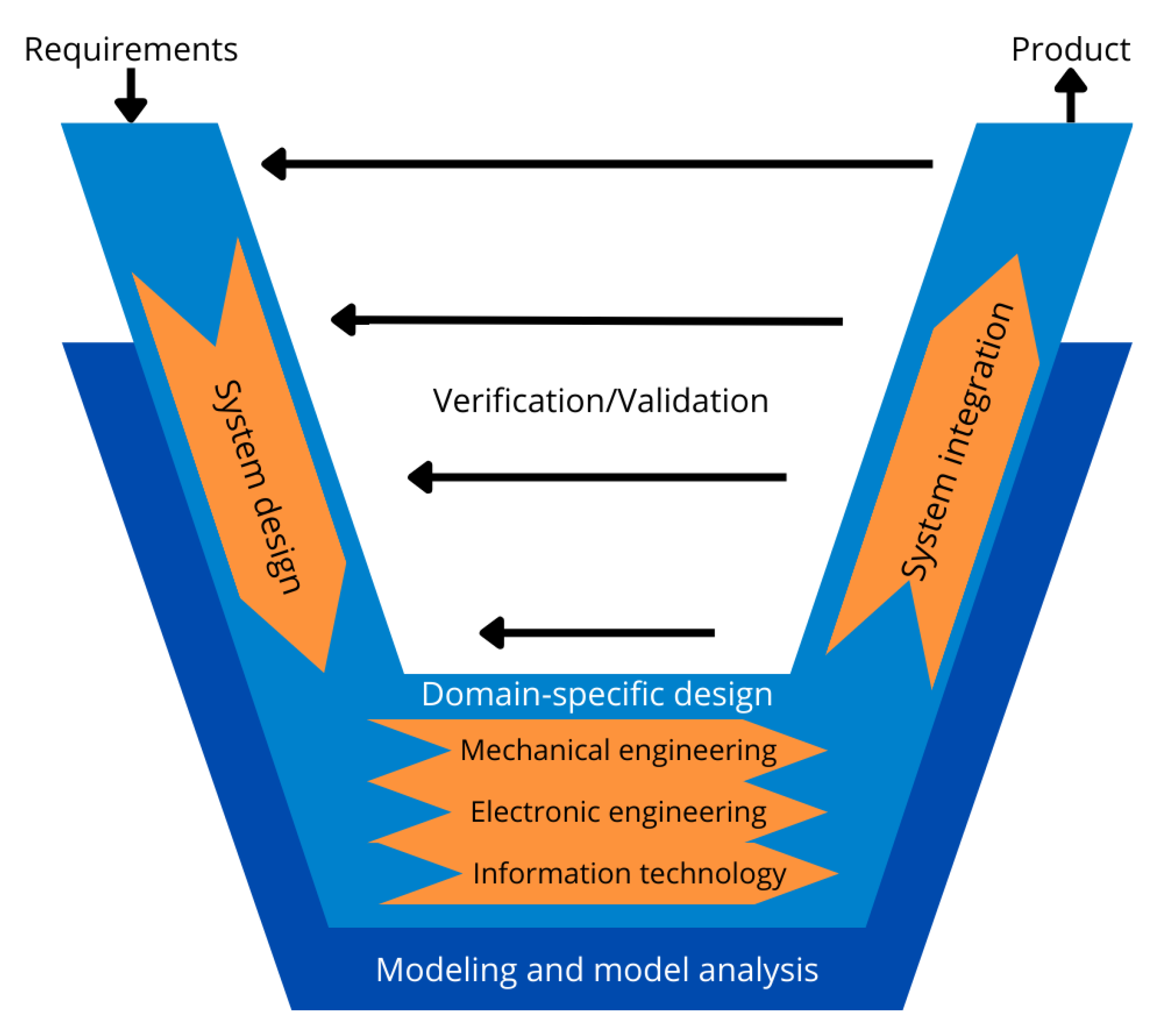

2.2. VDI 2206

2.3. System Design

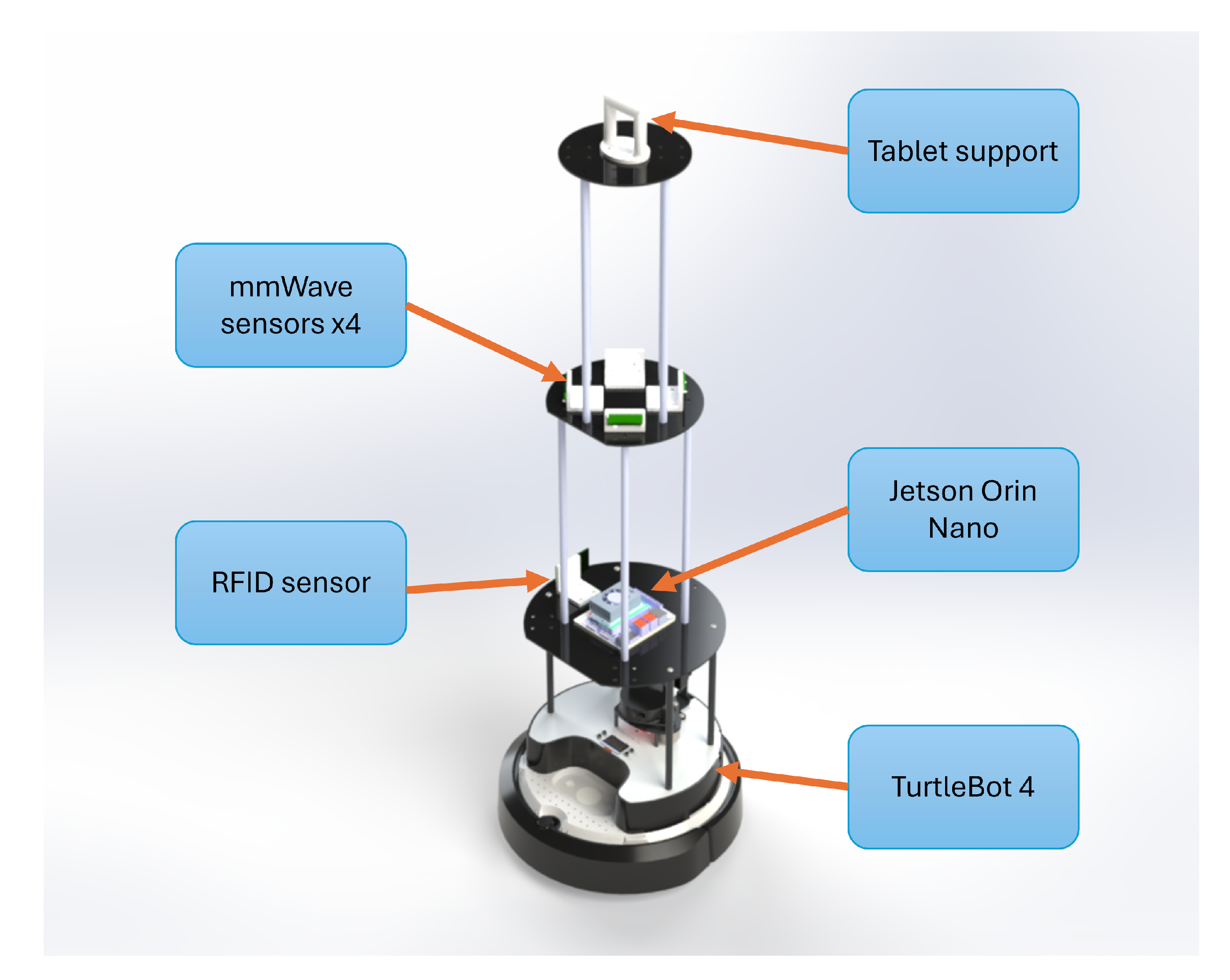

2.3.1. Mechanical Design

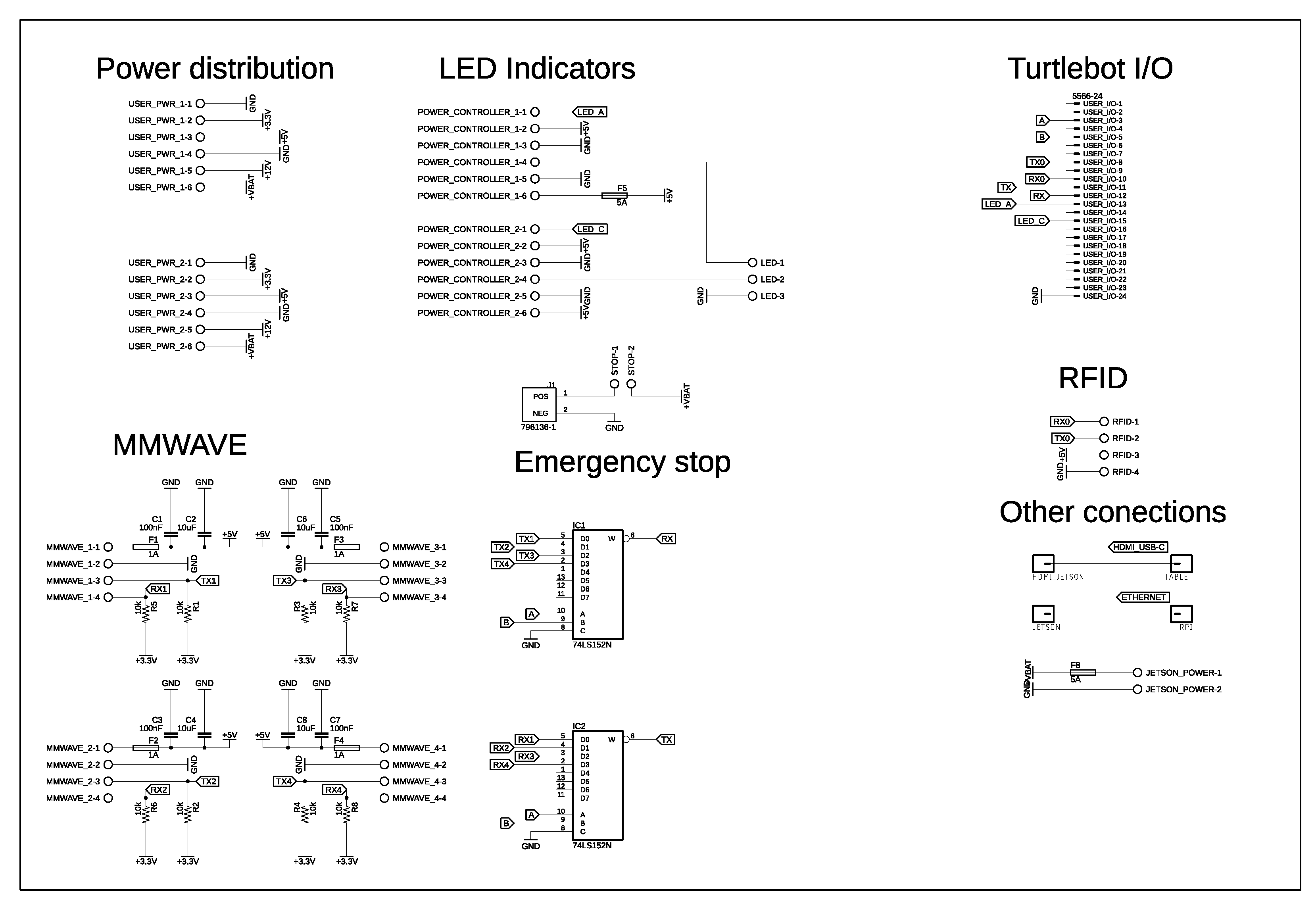

2.3.2. Electronic Design

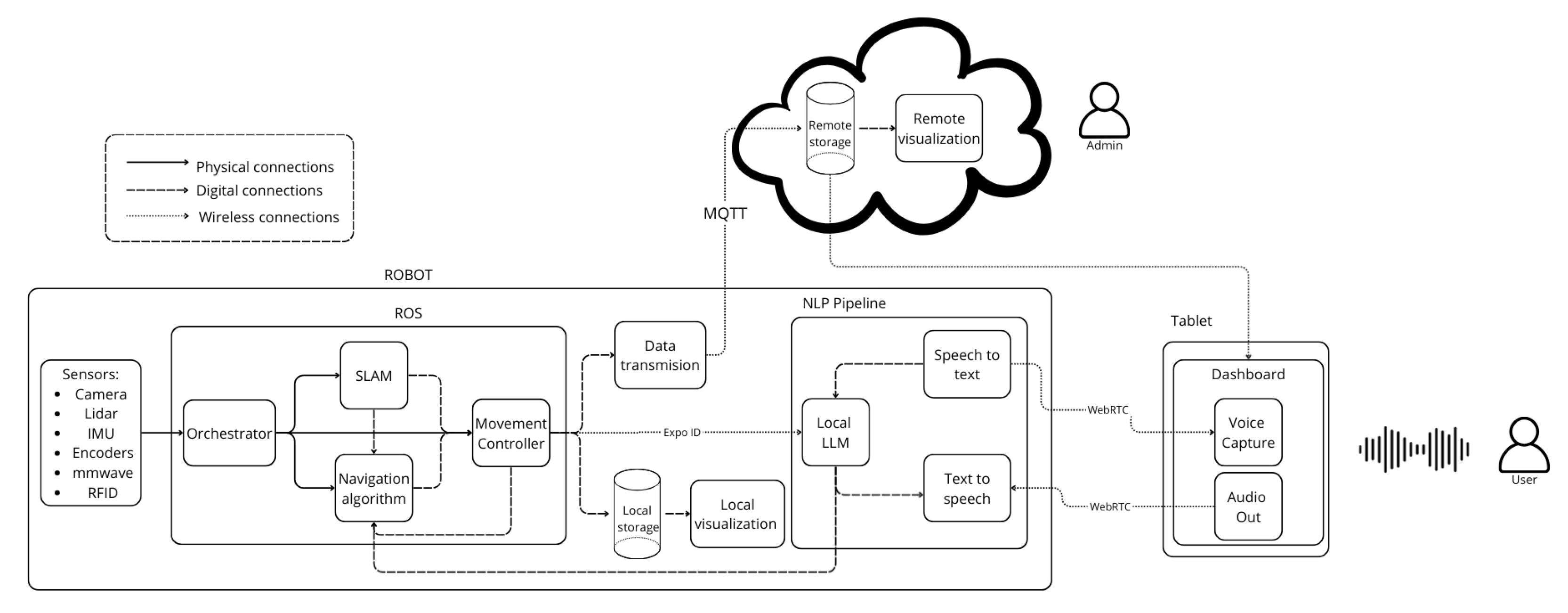

2.3.3. Information Technology Design

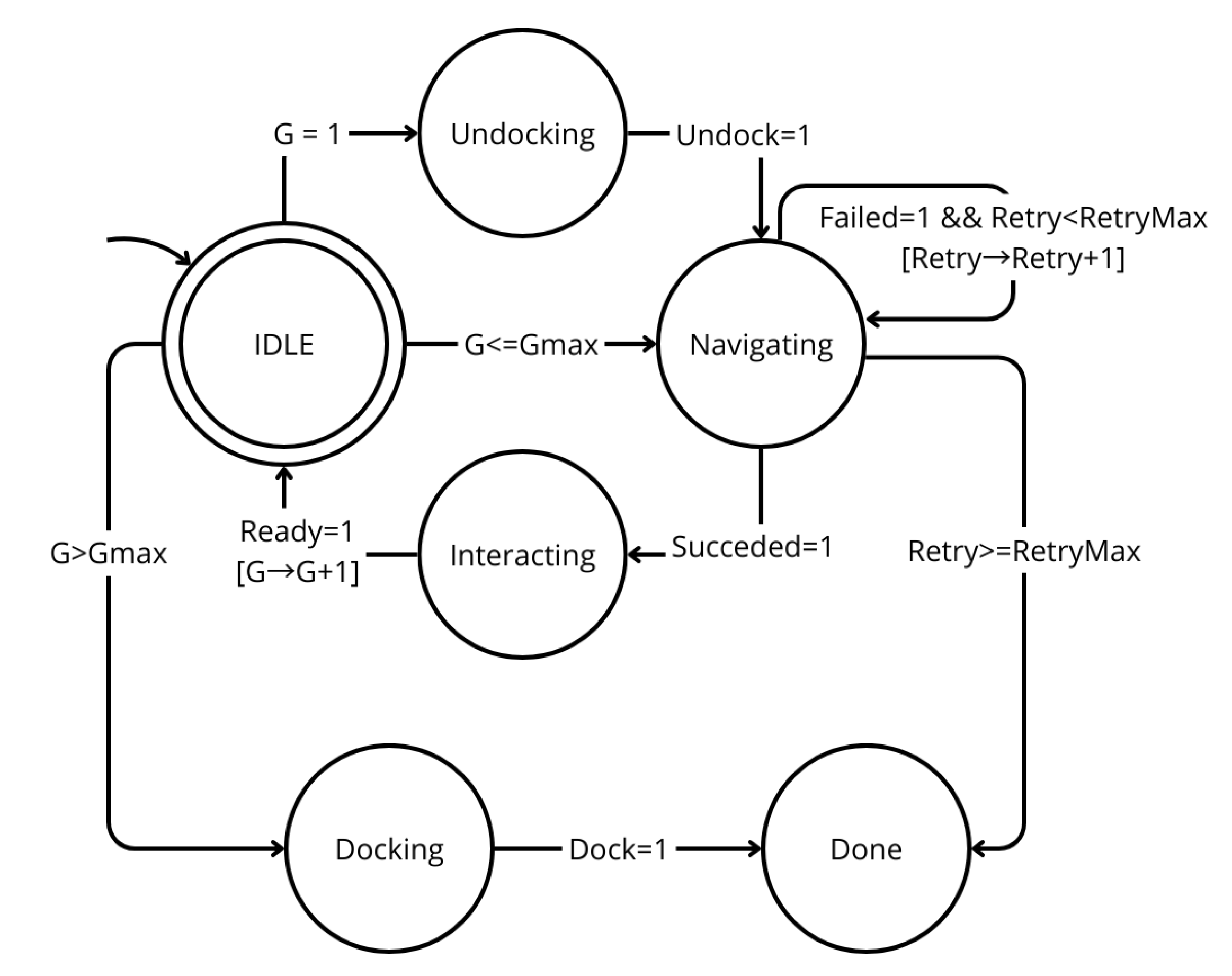

- Idle: Initial waiting state where the system decides the next action depending on whether the mission has just started, a navigation goal remains, or all goals have been completed.

- Undock: Triggered at the beginning of a mission, this state commands the robot to disengage from the docking station using a service client. Upon success, the FSM transitions to navigation; on failure, it returns to the docking sequence.

- Navigate: In this state, the robot publishes navigation goals through a dedicated ROS topic. The FSM remains here until feedback is received via the/goal_status topic. If the goal succeeds, the FSM resets retries and transitions back to Idle to evaluate the next step. If it fails, the system retries navigation up to a maximum threshold before aborting the mission and returning to Dock. During this state, the FSM invokes the ROS 2 go_to_pose routine, which incorporates dynamic obstacle avoidance by recalculating the path whenever new obstacles such as visitors entering the robot’s trajectory. This reactive behavior allows the robot to adapt to changing conditions in real time, maintaining both safety and mission continuity during autonomous tours.

- Dock: Commands the robot to return to and connect with its docking station. Successful docking leads to the Done state, while failure also results in mission termination.

- Done: Final state where the FSM halts execution, signaling that the mission has either been completed successfully or aborted due to failure.

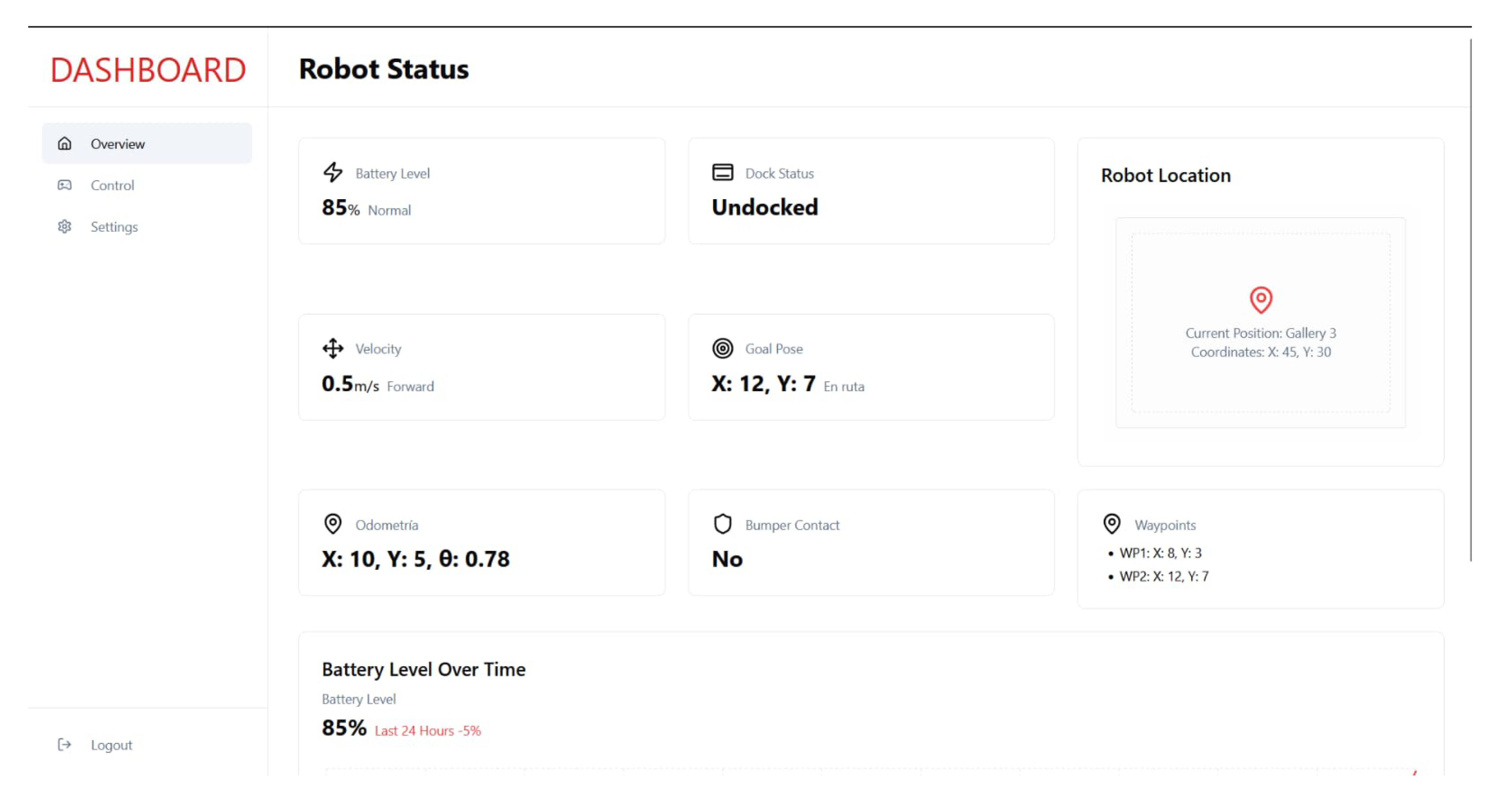

- Overview Dashboard: Displays the robot’s operational status, including battery level, docking state, odometry, velocity, navigation goals, and current location within the museum. It also provides historical data, such as battery trends over time, and highlights waypoint tracking to ensure mission progress.

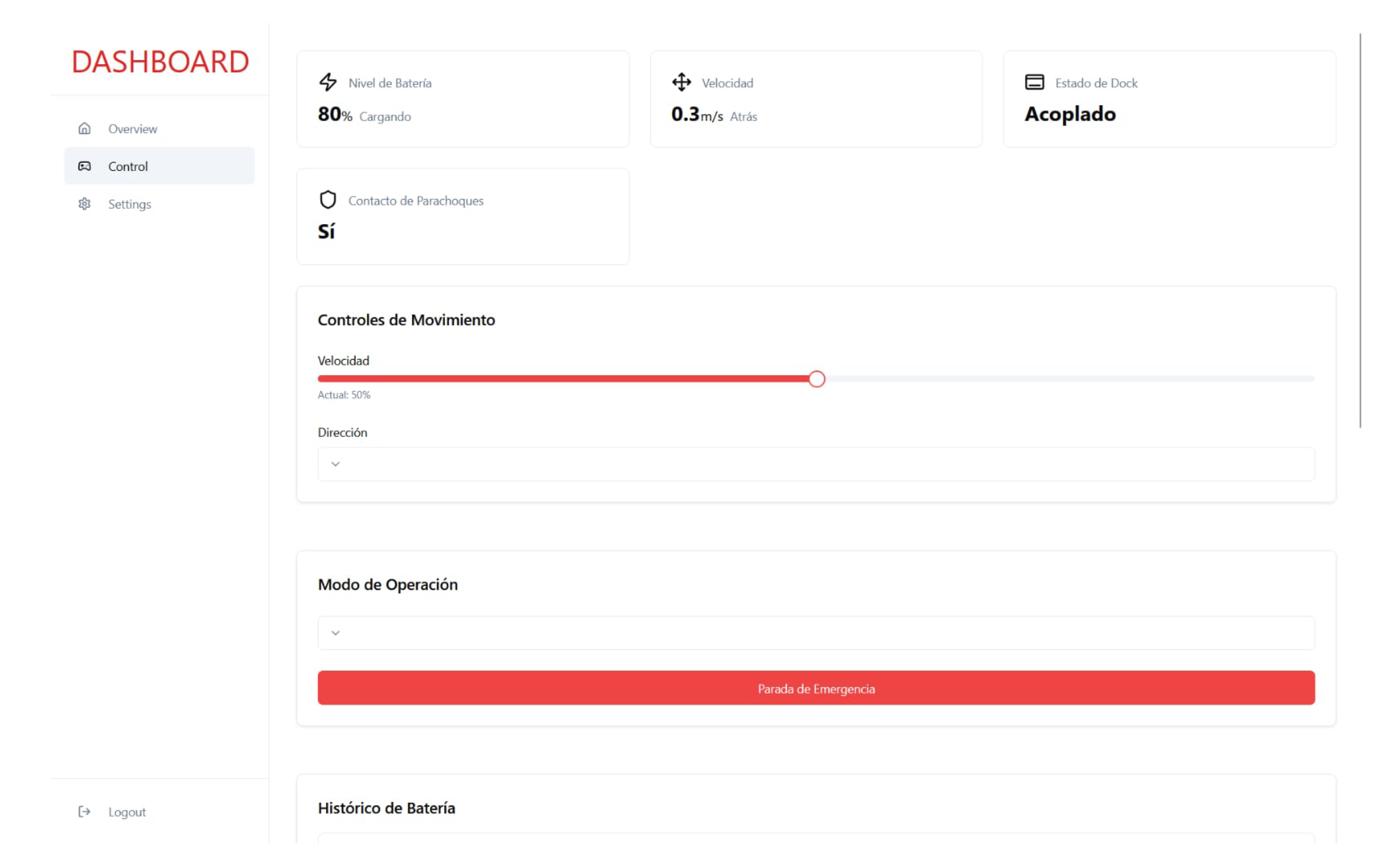

- Control Dashboard: Focused on direct robot management, it allows operators to adjust motion parameters such as speed and direction, select the operating mode, and trigger emergency stop commands. Additional status indicators include bumper contact, charging state, and docking confirmation, offering a clear view of safety and mobility conditions.

3. Results and Discussion

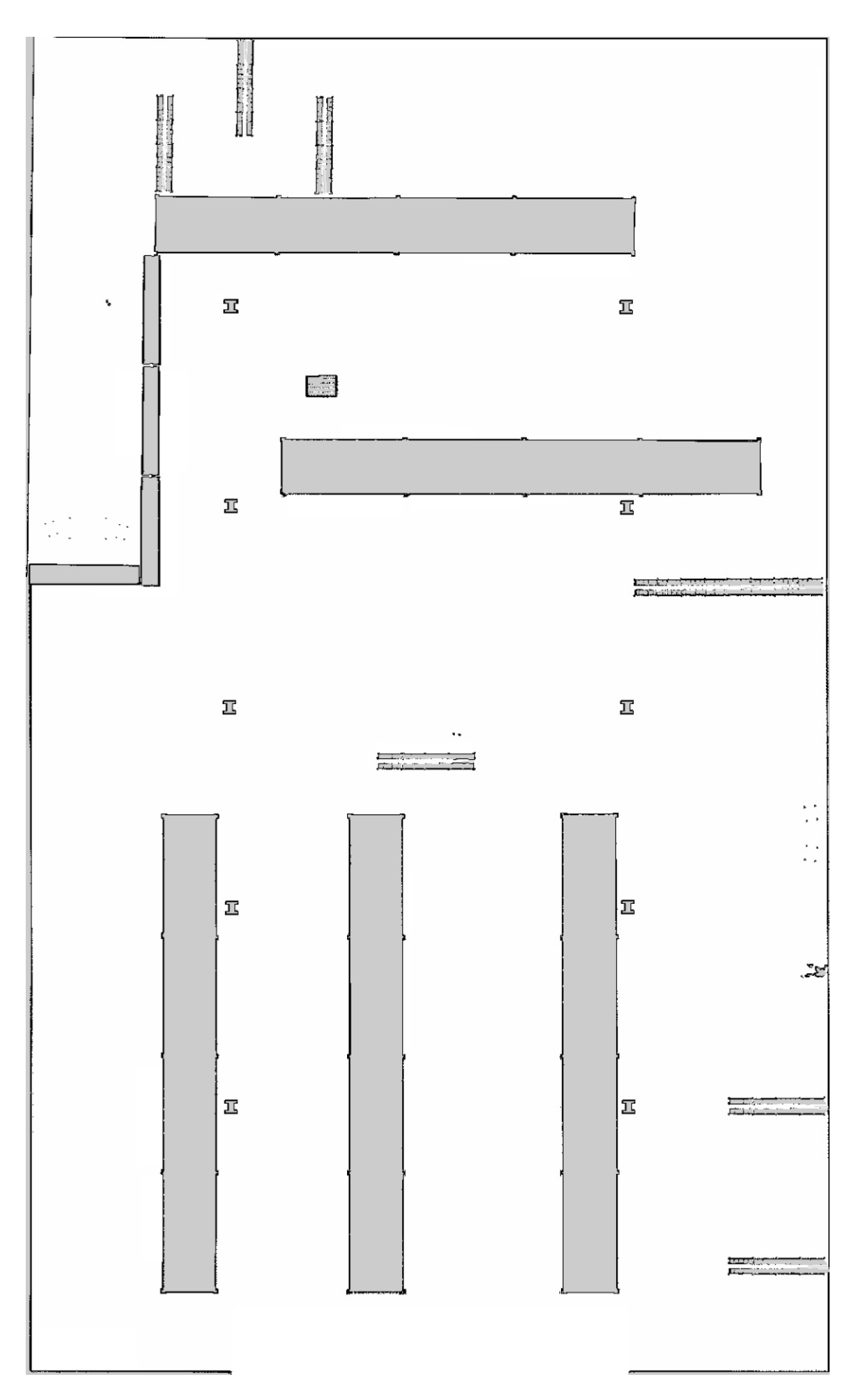

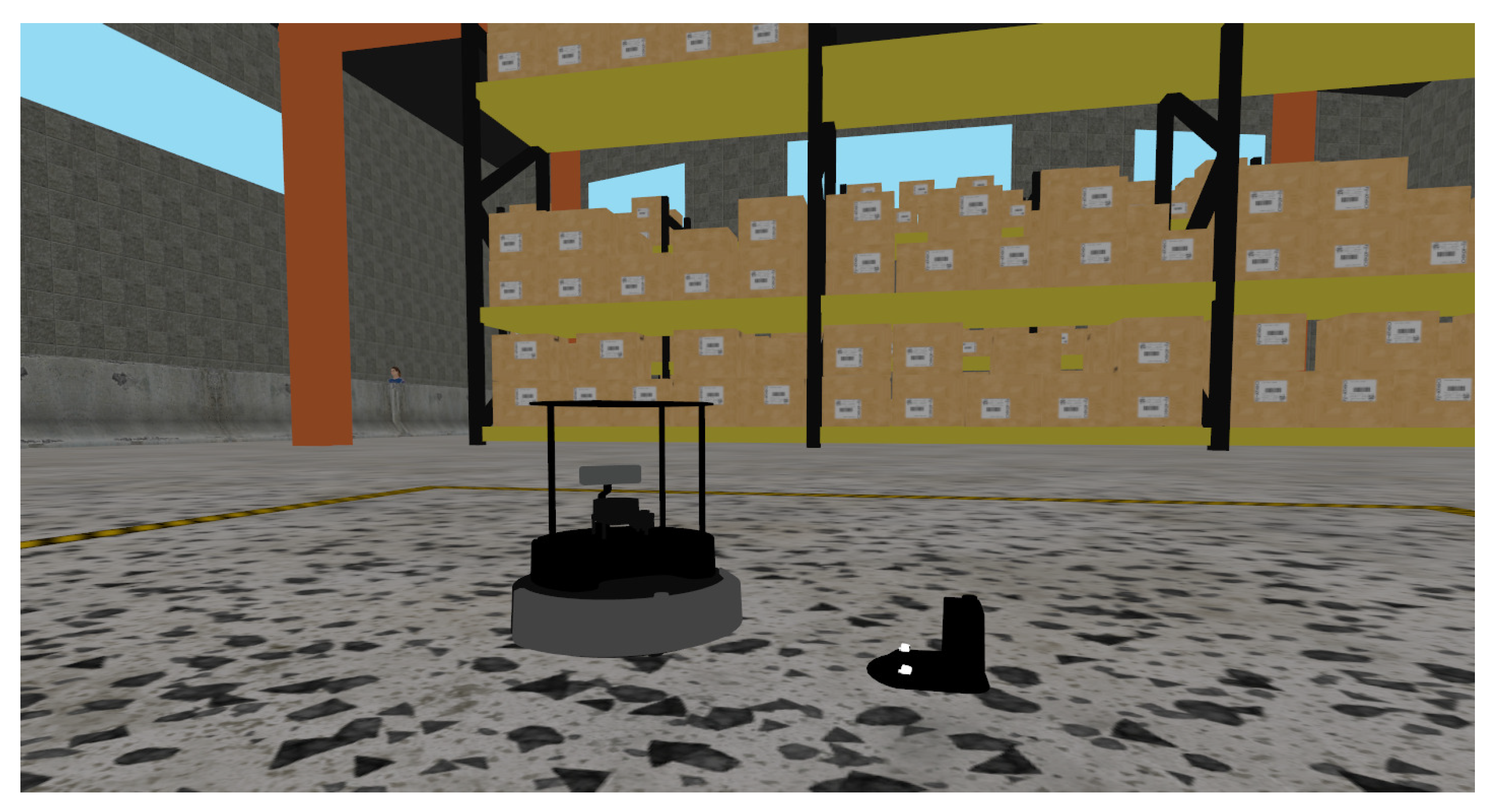

3.1. Simulation

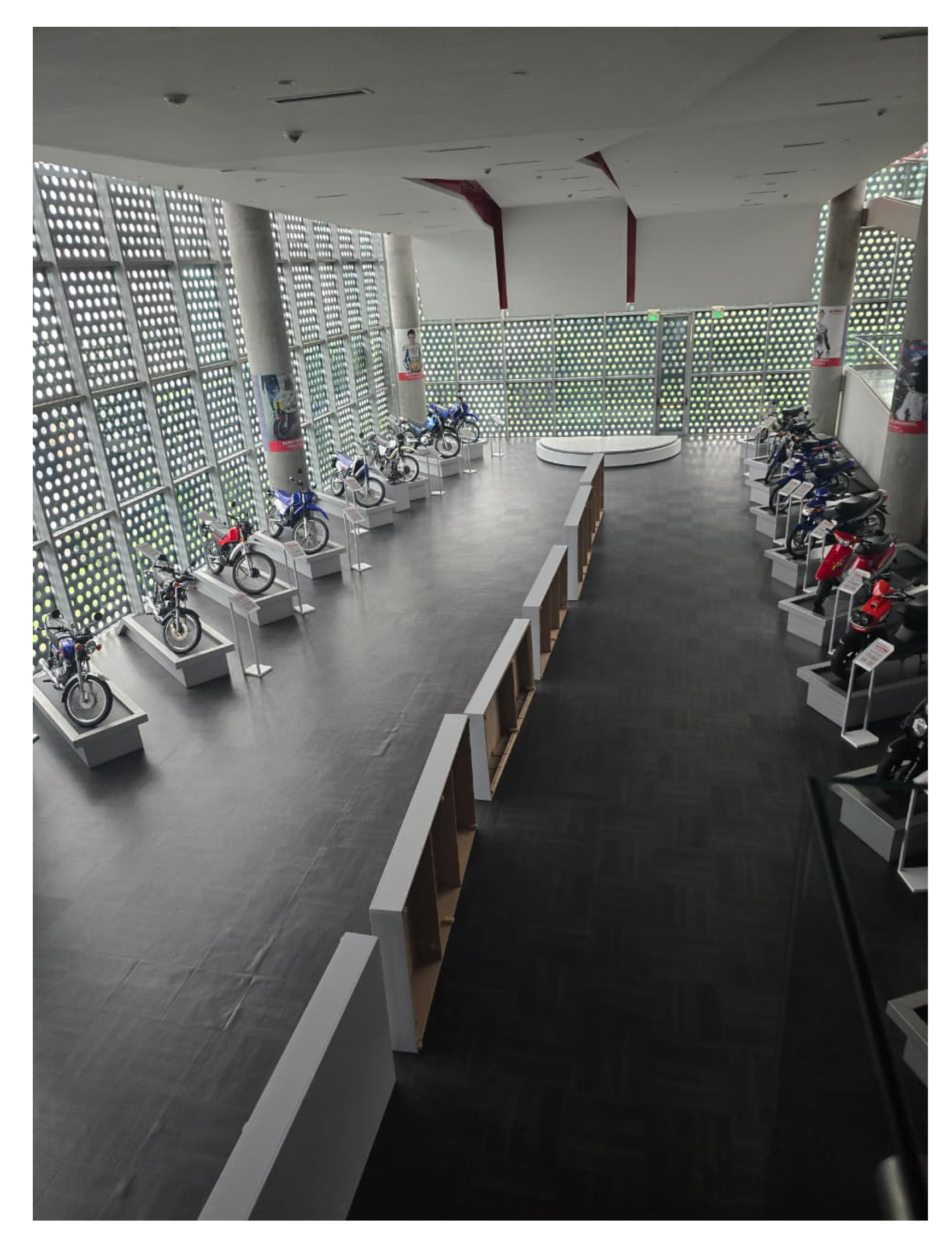

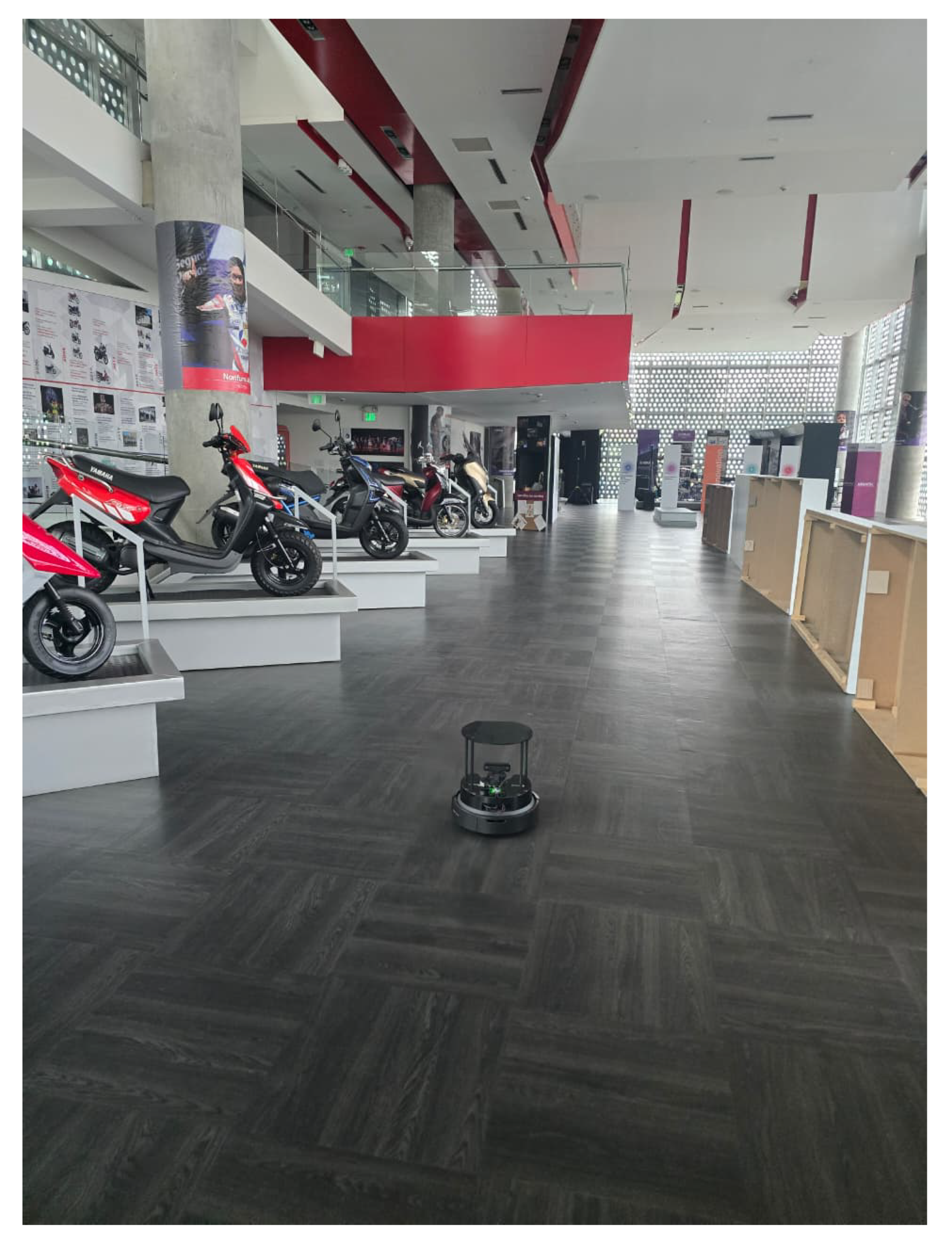

3.2. Initial Deployment and Validation

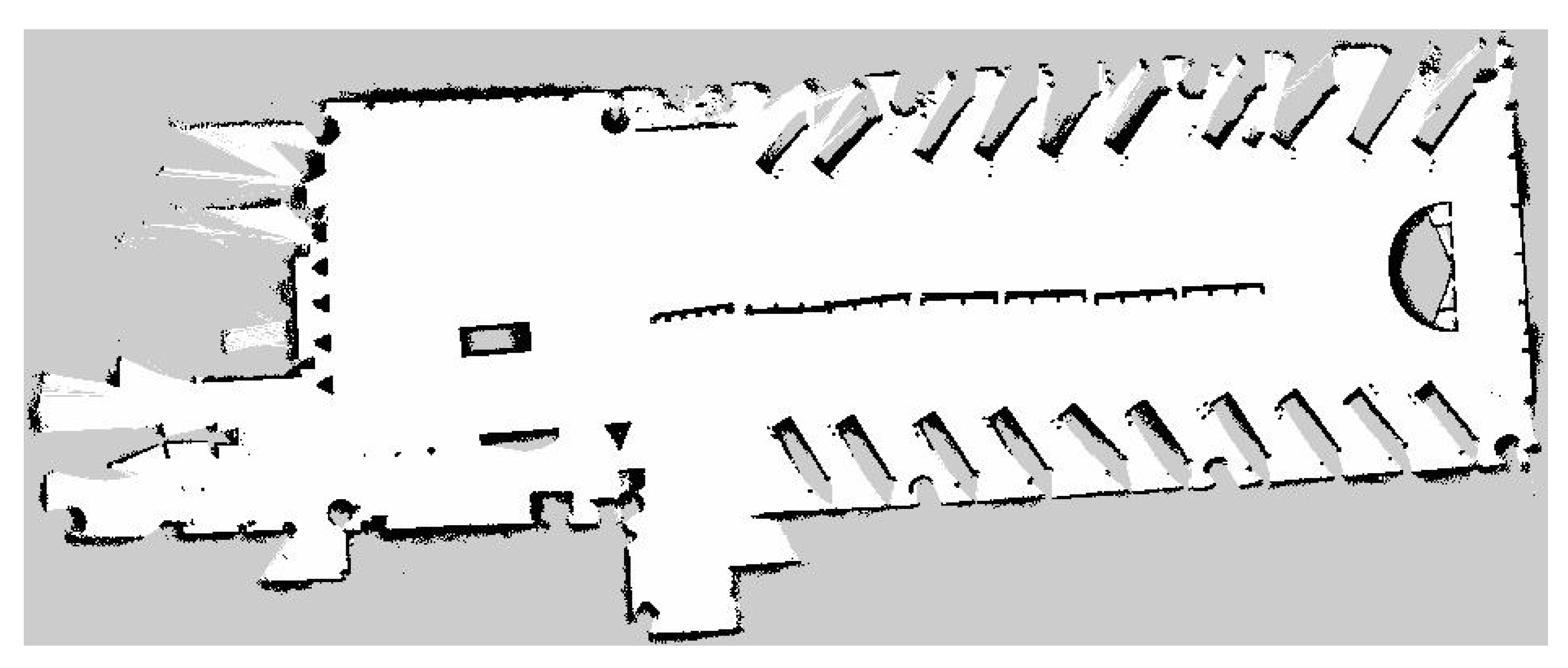

3.2.1. Robot Mapping and Navigation

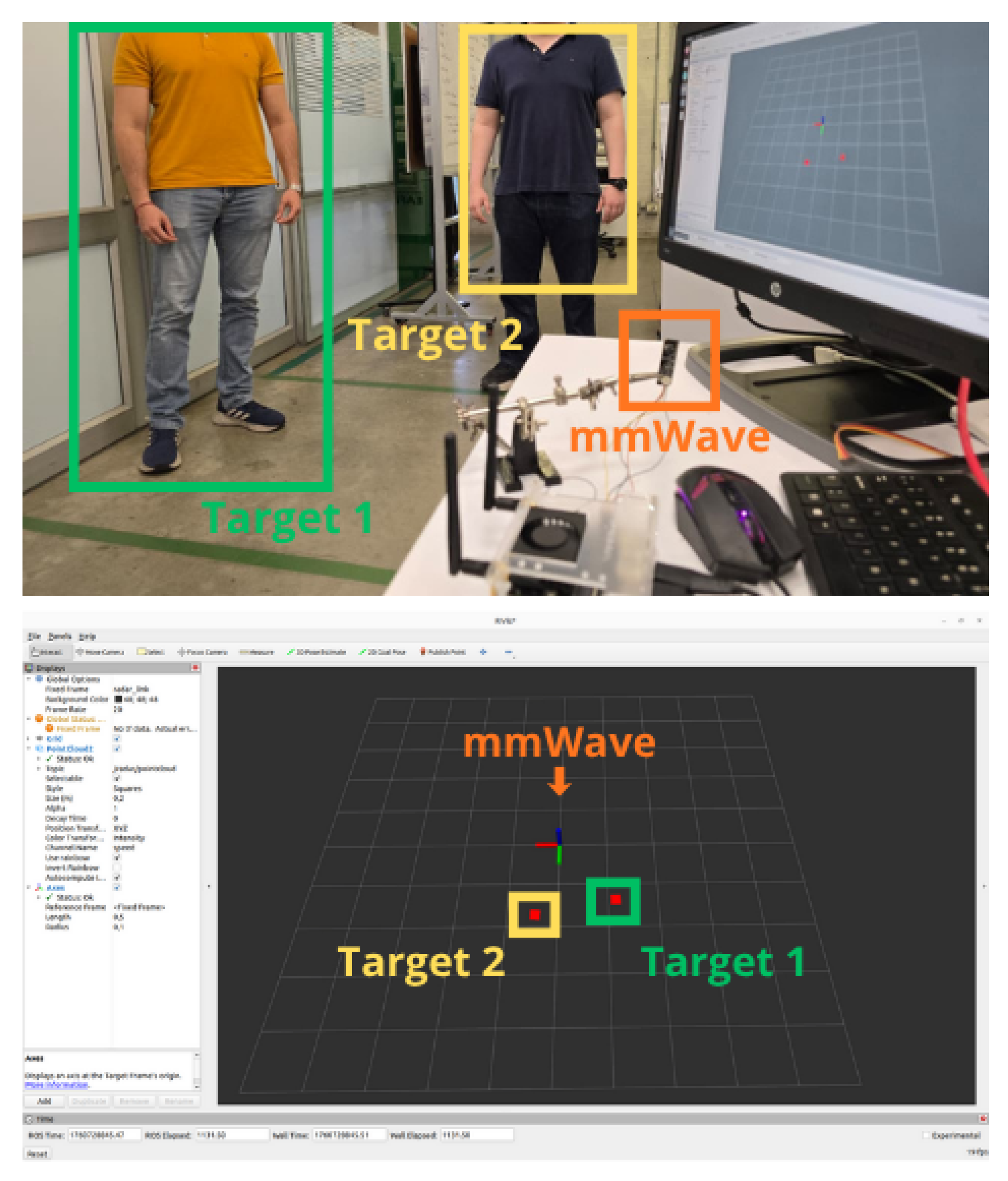

3.2.2. mmWave Sensor Evaluation

3.2.3. Language Model and Robot Body

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FSM | Finite State Machine |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| RFID | Radio-Frequency Identification |

| RGBD | Red-Green-Blue-Depth (sensor/camera) |

| ROS | Robot Operating System |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization and Mapping |

| STT | Speech-to-Text |

| TTS | Text-to-Speech |

References

- Hu, K.; Chen, Z.; Kang, H.; Tang, Y. 3D vision technologies for a self-developed structural external crack damage recognition robot. Autom. Constr. 2024, 159, 105262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, N.; Hellou, M.; Ahn, H. Deploying social robots in museum settings: A quasi-systematic review exploring purpose and acceptability. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2021, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickmore, T.; Pfeifer, L.; Schulman, D. Relational Agents Improve Engagement and Learning in Science Museum Visitors. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Virtual Agents, Reykjavik, Iceland, 15–17 September 2011; Vilhjálmsson, H.H., Kopp, S., Marsella, S., Thórisson, K.R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kayukawa, S.; Sato, D.; Murata, M.; Ishihara, T.; Takagi, H.; Morishima, S.; Asakawa, C. Enhancing Blind Visitor’s Autonomy in a Science Museum Using an Autonomous Navigation Robot. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellou, M.; Lim, J.; Gasteiger, N.; Jang, M.; Ahn, H.S. Technical Methods for Social Robots in Museum Settings: An Overview of the Literature. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2022, 14, 1767–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, M.; Galán, R.; Matía, F.; Rodríguez-Losada, D.; Jiménez, A. An emotional model for a guide robot. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Part A Syst. Humans 2010, 40, 982–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, S.; Randazzo, M.; Landini, E.; Bernagozzi, S.; Sacco, G.; Piccinino, M.; Natale, L. Tour guide robot: A 5G-enabled robot museum guide. Front. Robot. AI 2023, 10, 1323675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daza, M.; Barrios-Aranibar, D.; Diaz-Amado, J.; Cardinale, Y.; Vilasboas, J. An approach of social navigation based on proxemics for crowded environments of humans and robots. Micromachines 2021, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchetto, F.; Baxter, P.; Hanheide, M. Lindsey the Tour Guide Robot—Usage Patterns in a Museum Long-Term Deployment. In Proceedings of the 2019 28th IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, RO-MAN 2019, New Delhi, India, 14–18 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, C.G. Technology Readiness Levels; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda, Y.D.V.; Martins, L.E.G.; Cappabianco, F.A.M. Autonomous Visual Navigation for Mobile Robots: A Systematic Literature Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareschi, R. Beyond Human and Machine: An Architecture and Methodology Guideline for Centaurian Design. Sci 2024, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, J.C.; Toro-Ossaba, A.; López-Gonzalez, A.; Hernandez-Martinez, E.G.; Sanin-Villa, D. A Review of Multi-Robot Systems and Soft Robotics: Challenges and Opportunities. Sensors 2025, 25, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alletto, S.; Cucchiara, R.; Fiore, G.D.; Mainetti, L.; Mighali, V.; Patrono, L.; Serra, G. An Indoor Location-Aware System for an IoT-Based Smart Museum. IEEE Internet Things J. 2016, 3, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, Z.; Erdemir, G. Experimental Comparison of Global Planners for Trajectory Planning of Mobile Robots in an Unknown Environment with Dynamic Obstacles. In Proceedings of the HORA 2023–2023 5th International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications, Proceedings, Istanbul, Turkey, 8–10 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Atif, M.; Daniyal, S.; Ahmed, L.; Memon, B.; Pasta, Q. Navigating the Maze Environment in ROS-2: An Experimental Comparison of Global and Local Planners for Dynamic Trajectory Planning in Mobile Robots. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Robotics and Automation in Industry, ICRAI 2024, Rawalpindi, Pakistan, 18–19 December 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, K.; Suresh, A.K.; Ender, A.; Gotad, S.; Maniyar, S.; Anand, S.; Noghabaei, M.; Han, K.; Lobaton, E.; Wu, T. An integrated UGV-UAV system for construction site data collection. Autom. Constr. 2020, 112, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjourian, N.; Nguyen, V. Multimodal object detection using depth and image data for manufacturing parts. In Proceedings of the International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, Greenville, SC, USA, 23–27 June 2025; Volume 89022, p. V002T16A001. [Google Scholar]

- Soumya, A.; Mohan, C.K.; Cenkeramaddi, L.R. Recent Advances in mmWave-Radar-Based Sensing, Its Applications, and Machine Learning Techniques: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 8901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harlow, K.; Jang, H.; Barfoot, T.D.; Kim, A.; Heckman, C. A new wave in robotics: Survey on recent mmwave radar applications in robotics. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2024, 40, 4544–4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazempour, B.; Bhattathiri, S.; Rashedi, E.; Kuhl, M.; Hochgraf, C. Framework for Human-Robot Communication Gesture Design: A Warehouse Case Study. SSRN Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Park, C.H. Empathetic Robot with Transformer-Based Dialogue Agent. In Proceedings of the 2021 18th International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots (UR), Gangneung, Republic of Korea, 12–14 July 2021; pp. 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Kapadia, D.R. Large Language Models in Robotics: A Survey on Integration and Applications. Machines 2023, 6, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promobot. Home. Available online: https://promo-bot.ai/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Rueda-Carvajal, G.D.; Tobar-Rosero, O.A.; Sánchez-Zuluaga, G.J.; Candelo-Becerra, J.E.; Flórez-Celis, H.A. Opportunities and Challenges of Industries 4.0 and 5.0 in Latin America. Sci 2025, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espina-Romero, L.; Hurtado, H.G.; Parra, D.R.; Pirela, R.A.V.; Talavera-Aguirre, R.; Ochoa-Díaz, A. Challenges and Opportunities in the Implementation of AI in Manufacturing: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sci 2024, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, I. Comparison of three methodological approaches of design research. In Proceedings of the ICED 2007, the 16th International Conference on Engineering Design, Paris, France, 28–31 July 2007; Volume DS 42. [Google Scholar]

- Graessler, I.; Hentze, J. The new V-Model of VDI 2206 and its validation das Neue V-Modell der VDI 2206 und seine Validierung. At-Automatisierungstechnik 2020, 68, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Santacruz, J.A.; Portillo-Velez, R.; Torres-Figueroa, J.; Marin-Urias, L.F.; Portilla-Flores, E. Towards an integrated design methodology for mechatronic systems. Res. Eng. Des. 2023, 34, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, I. Differences between ‘research in design context’ and ‘design inclusive research’ in the domain of industrial design engineering. J. Des. Res. 2008, 7, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Rojas, J.K.; Andrade-Miranda, K.S.; Justiniano-Medina, A.; Vasquez, C.A.A.; Beraún-Espíritu, M.M. Design and Implementation of an Automated Robotic Bartender Using VDI 2206 Methodology. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 465, 02062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graessler, I.; Hentze, J.; Bruckmann, T. V-models for interdisciplinary systems engineering. In Proceedings of the International Design Conference, DESIGN, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 20–23 May 2018; Volume 2, pp. 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Specification/Version |

|---|---|

| Main Controller | NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano |

| LiDAR | RPLIDAR-A1 |

| Depth Camera | OAK-D-PRO |

| Software Stack | ROS2 Humble Hawksbill |

| Simulation Environment | Gazebo + RViz |

| Robotic platform | TurtleBot 4 Standard Version |

| Wireless Communication | Wi-Fi + MQTT for IoT integration |

| Visitors interaction | Tablet |

| Exhibition Identification | RFID Reader M7E-HECTO |

| Human Detection | Rd-03D mmWave Sensor |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arteaga-Vargas, A.; Velásquez, D.; Giraldo-Pérez, J.P.; Sanin-Villa, D. Development of an Autonomous and Interactive Robot Guide for Industrial Museum Environments Using IoT and AI Technologies. Sci 2025, 7, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040175

Arteaga-Vargas A, Velásquez D, Giraldo-Pérez JP, Sanin-Villa D. Development of an Autonomous and Interactive Robot Guide for Industrial Museum Environments Using IoT and AI Technologies. Sci. 2025; 7(4):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040175

Chicago/Turabian StyleArteaga-Vargas, Andrés, David Velásquez, Juan Pablo Giraldo-Pérez, and Daniel Sanin-Villa. 2025. "Development of an Autonomous and Interactive Robot Guide for Industrial Museum Environments Using IoT and AI Technologies" Sci 7, no. 4: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040175

APA StyleArteaga-Vargas, A., Velásquez, D., Giraldo-Pérez, J. P., & Sanin-Villa, D. (2025). Development of an Autonomous and Interactive Robot Guide for Industrial Museum Environments Using IoT and AI Technologies. Sci, 7(4), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040175