Processing and Characterization of AlN–SiC Composites Obtained by Spark Plasma Sintering

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Powder Processing and Sintering

2.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD), Density, Hardness, and Microstructure Characterization

2.3. Dielectric, Electrical, and Microwave Absorption Properties

3. Results and Discussion

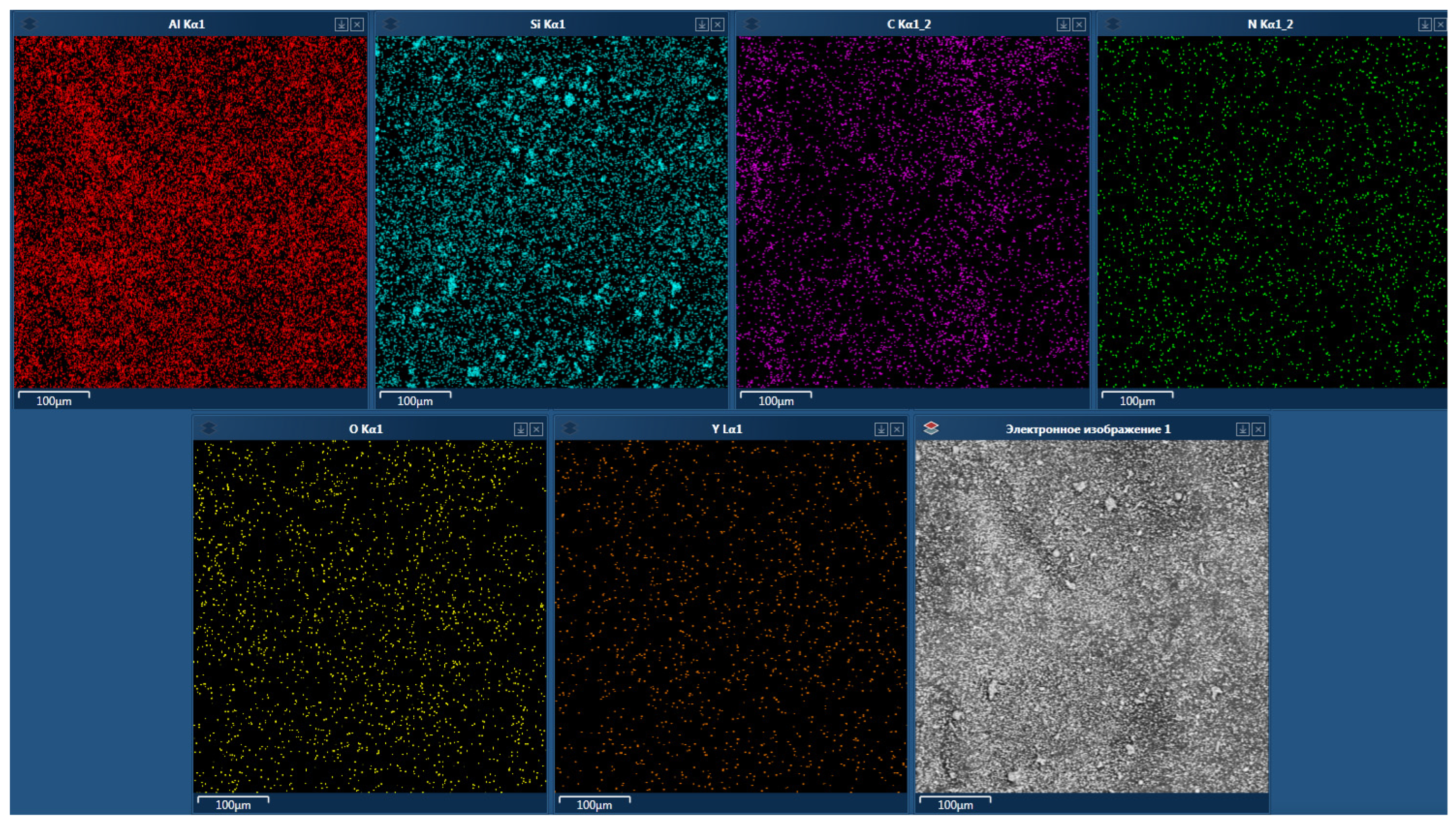

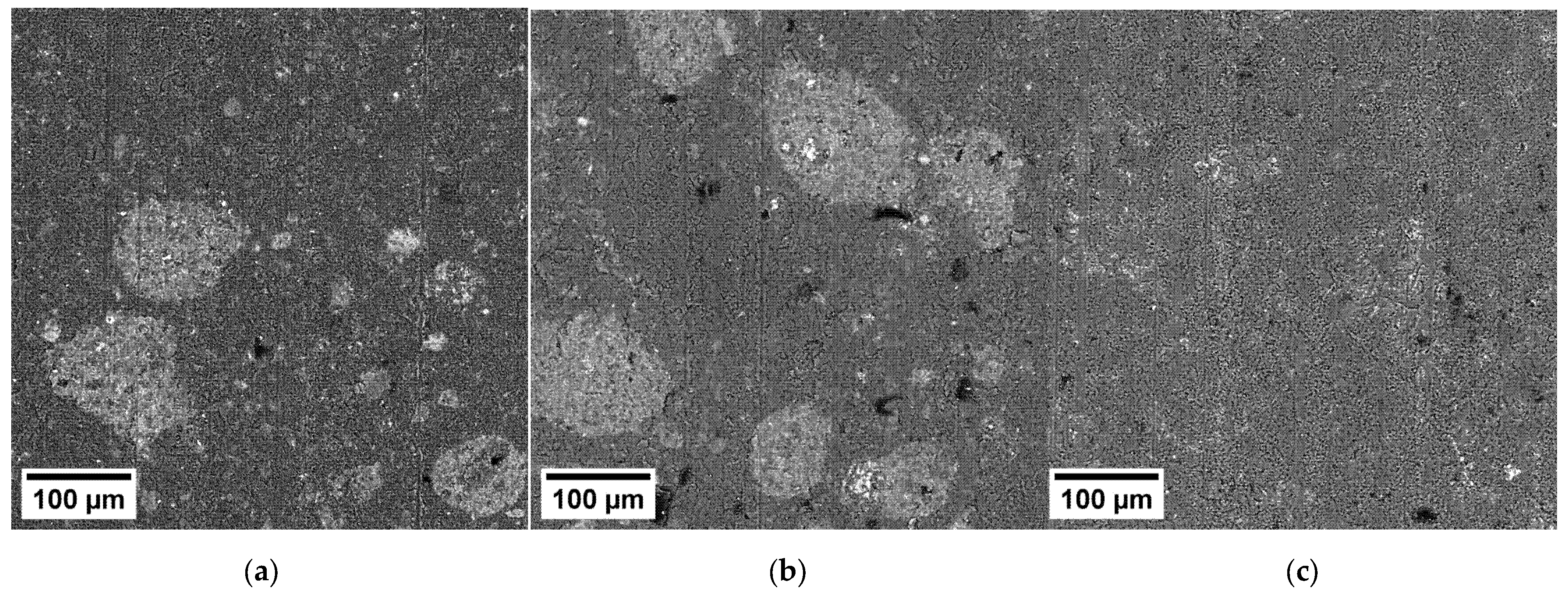

3.1. Density, Phase Compositions, and Microstructure

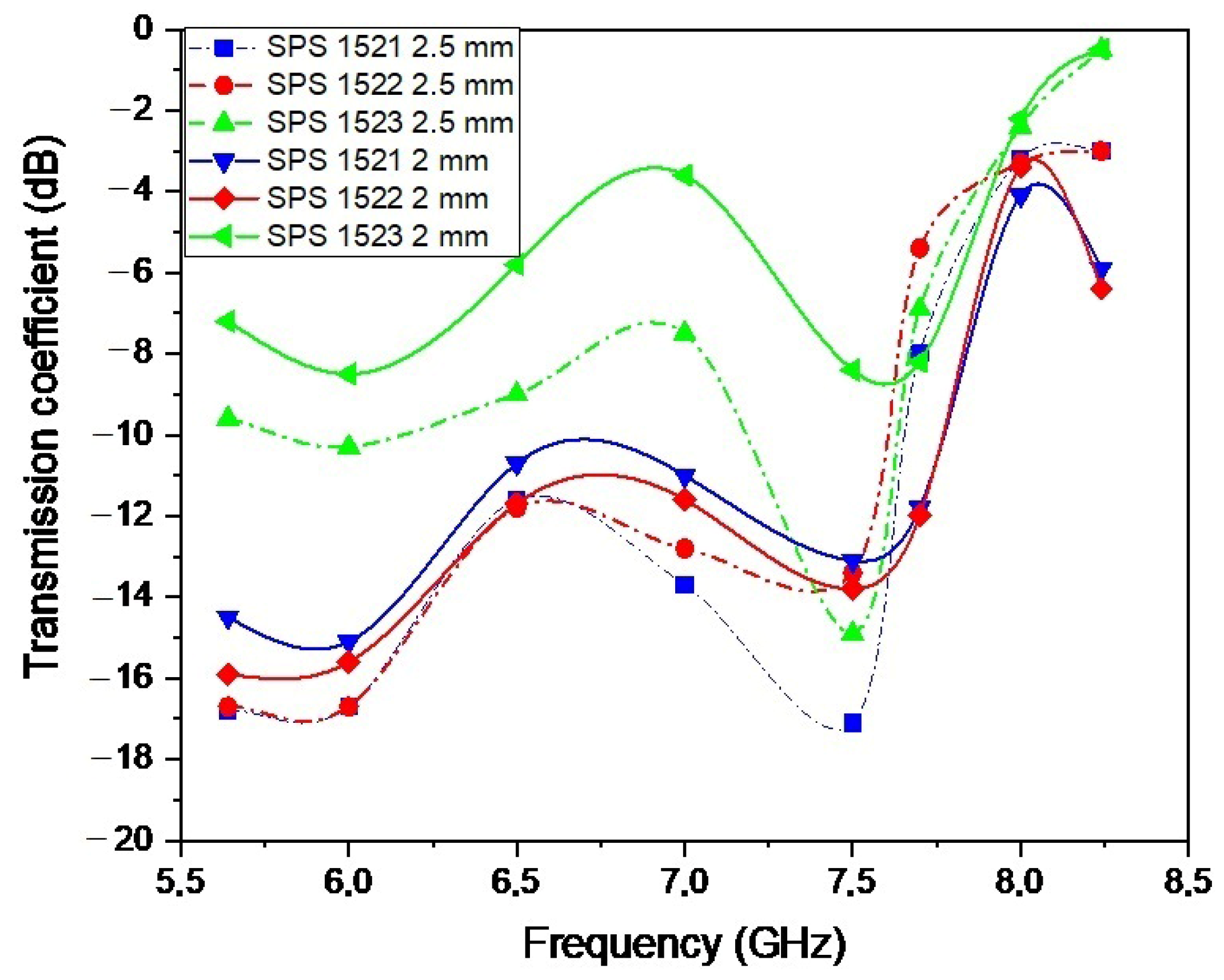

3.2. Microwave Absorption, Dielectric and Electrical Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Белoва, Г.С.; Титoва, Ю.В.; Самбoрук, А.Р. Пoлучение керамическoй нитриднo-карбиднoй нанoпoрoшкoвoй кoмпoзиции AlN-SiC пo азиднoй технoлoгии СВС. Сoвременные Материалы Техника и Технoлoгии 2020, 3, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang-Yu, Z.; Shou-Hong, T.; Wei-Wei, X.; Shao-Ming, D.; Zheng-Ren, H.; Ye, D.; Pei-Heng, W.; Dong-Liang, J. Preparation and dielectric properties of SiC-AlN solid solutions. Key Eng. Mater. 2005, 280–283, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Jiang, S.; Pan, L.; Yin, S.; Qiu, T.; Yang, J.; Li, X. β-SiC/AlN microwave attenuating composite ceramics with excellent and tunable microwave absorption properties. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 6385–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbenyuk, T.B.; Prikhna, T.O.; Sverdun, V.B.; Chasnyk, V.I.; Karpets, M.V.; Basyuk, T.V. The effect of size of the SiC inclusions in the AlN-SiC composite structure on the electrophysical properties. J. Superhard Mater. 2016, 38, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zang, X.; Du, B. Investigation of the effect of the SiC particle size on the properties of the AlN–SiC composite ceramic. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 261, 124222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Sang, L.; Pan, B.; Feng, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, X. Thermal Conductivity and High-Frequency Dielectric Properties of Pressureless Sintered SiC-AlN Multiphase Ceramics. Materials 2018, 11, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prikhna, T.O.; Serbenyuk, T.B.; Sverdun, V.B.; Chasnyk, V.I.; Karpets, M.V.; Basyuk, T.V.; Dellikh, J. Formation regulations of structures of AlN-SiC-based ceramic materials. J. Superhard Mater. 2015, 37, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyganenko, V.S.; Lytyuga, N.V.; Dubovik, T.V.; Kozina, G.K.; Rogozinskaya, A.A.; Panashenko, V.M. Effect of the Al2O3 additives on the properties of the ceramic based on aluminum nitride. Powder Metall. 2006, 9, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepochatov, Y.; Zemnitskaya, A.; Mul, P. The development of ceramics based on aluminum nitride for products of electronic engineering. Mod. Electron. 2011, 9, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-W.; Mitomo, M.; Nishiruma, T. Heat-resistant silicon carbide with aluminum nitride and erbium oxide. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2001, 84, 2060–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Jia, C.C.; Cao, W.B. Dielectric properties of spark plasma sintered AlN/SiC composite ceramics. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2014, 21, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirouzu, K.; Nonaka, Y.; Hotta, M.; Enomoto, N.; Hojo, J. Synthesis and microstructural evaluation of SiC-AlN composites. Key Eng. Mater. 2007, 352, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Сафаралиев, Г.К.; Шабанoв, Ш.Ш.; Садыкoв, С.А.; Агаларoв, А.Ш.; Билалoв, Б.А. Диэлектрическая релаксация в пoликристаллических твердых раствoрах SiC–AlN. Вестник Дагестанскoгo Гoсударственнoгo Университета 2011, 6, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Feng, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, Y.; Gong, H.; Zhang, Y. The dielectric and microwave absorption properties of polymer-derived SiCN ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 38, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.W.; Wang, C.B.; Liu, H.X.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, L.M. Structural, thermal and dielectric properties of AlN–SiC composites fabricated by plasma activated sintering. Adv. Appl. Ceram. 2019, 118, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangvil, A.; Ruh, R. Phase Relationships in the Silicon Carbide—Aluminum Nitride System. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1988, 71, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís Pinargote, N.W.; Pristinskiy, Y.; Meleshkin, Y.; Kurmysheva, A.Y.; Mozhaev, A.; Lavreshin, N.; Smirnov, A. Prediction of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Al2O3–TiB2–TiC Composites Using Design of Mixture Experiments. Ceramics 2024, 7, 1639–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.N.; Pristinskiy, Y.; Soe, T.N.; Malakhinsky, A.; Mosyanov, M.; Podrabinnik, P.; Smirnov, A.; Solís Pinargote, N.W. Processing and Characterization of Spark Plasma Sintered SiC-TiB2-TiC Powders. Materials 2022, 15, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.; Pristinskiy, Y.; Pinargote, N.W.S.; Meleshkin, Y.; Podrabinnik, P.; Volosova, M.; Grigoriev, S. Mechanical Performance and Tribological Behavior of WC-ZrO2 Composites with Different Content of Graphene Oxide Fabricated by Spark Plasma, Sintering. Sci 2024, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Tan, S.H.; Zhang, J.X.; Jiang, D.L.; Hu, B.; Gao, C. Lossy AlN–SiC composites fabricated by spark plasma sintering. J. Mater. Res. 2004, 19, 2759–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojo, J.; Nonaka, Y.; Kamada, K.; Enomoto, N.; Hotta, M.; Shirouzu, K. Fabrication and electrical property of SiC-AlN composites. Mater. Sci. Forum 2007, 561–565, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojo, J.; Matsuura, H.; Hotta, M. Nano-Grained Microstructure Design of Silicon Carbide Ceramics by SPS Process. Key Eng. Mater. 2009, 403, 177–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, R.; Tatami, J.; Wei Chen, I.; Wakihara, T.; Komeya, K.; Meguro, T. High temperature mechanical properties of dense AlN–SiC ceramics fabricated by spark plasma sintering without sintering additives. J. Amer. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94, 4150–4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, R.; Tatami, J.; Wakihara, T.; Komeya, K.; Meguro, T.; Goto, T.; Tu, R. Use of Post–heat Treatment to Obtain a 2H Solid Solution in Spark Plasma Sintering--Processed AlN–SiC Mixtures. J. Amer. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 91, 1548–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, A.M.; Ross, G.F. Measurement of the intrinsic properties of materials by time-domain techniques. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 1970, IM-19, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhomenko, M.P.; Kalenov, D.S.; Eremin, I.S.; Fedoseev, N.A.; Kolesnikova, V.M.; Dyakonova, O.A. Improving the accuracy in measuring the complex dielectric and magnetic permeabilities in the microwave range using the waveguide method. J. Commun. Technol. Electron. 2020, 65, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, M.; Uttamchand, N.K.; Annamalai, A.R.; Jen, C.-P. Insights on Spark Plasma Sintering of Magnesium Composites: A Review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olevsky, E.A.; Kandukuri, S.; Froyen, L. Consolidation enhancement in spark-plasma sintering: Impact of high heating rates. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 102, 114913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kultayeva, S.; Kim, Y.-W. Mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties of pressureless sintered SiC–AlN ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 19264–19273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Tanaka, H.; Kim, H. Formation of solid solutions between SiC and AlN during liquid-phase sintering. Mater. Lett. 1996, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, M.; Hojo, J. Inhibition of grain growth in liquid-phase sintered SiC ceramics by AlN additive and spark plasma sintering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 30, 2117–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besisa, D.H.A.; Ewais, E.M.M.; Shalaby, E.A.M.; Usenko, A.; Kuznetsov, D.V. Thermoelectric properties and thermal stress simulation of pressureless sintered SiC/AlN ceramic composites at high temperatures. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 182, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.B.; Qiu, J.H.; Morita, M.; Tan, S.H.; Jiang, D. The mechanical properties and microstructure of SiC–AlN particulate composite. J. Mater. Sci. 1998, 33, 1233–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubu, A.; Abbas, Z.; Hashim, M. Effect of Material Thickness on Attenuation (dB) of PTFE Using Finite Element Method at X-Band Frequency. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2014, 965912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deep, S.; Sharma, V. Effects of Microstructures, Heterogeneity, and Imperfectness on Propagation of SH-Waves in a Fiber-Reinforced Layer Sandwiched Between Two Microstructural Half-Spaces. Iran J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Mech. Eng. 2023, 47, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, R.; Tatami, J.; Wakihara, T.; Meguro, T.; Komeya, K. Temperature dependence of the electrical properties and Seebeck coefficient of AlN–SiC ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 89, 1295–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Kim, Y.W.; Lim, K.Y.; Nishimura, T.; Narimatsu, E. Electrical and thermal properties of SiC–AlN ceramics without sintering additives. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 2715–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, R.; Qin, H.; Gerhardt, R.A.; Ruh, R. Electrical properties of SiC-AlN composite. Ceram. Eng. Sci. Proc. 2003, 24, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Powder | N | O | Fe | C | Si | Al | Y | Free Si | Free C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlN + 3 wt.% Y2O3 | 32.01 | 1.62 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 63.81 | 2.36 | - | - |

| β-SiC | - | 1.33 | 0.05 | 28.55 | 69.4 | - | - | 0.42 | 0.25 |

| AlN | β-SiC | Y2O3 | Theor. Density | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% | 63.05 | 35.00 | 1.95 | 3.26 |

| vol.% | 63.14 | 35.59 | 1.27 |

| Sample Number | Sintering Temperature, °С | Pressure, MPa | Isothermal Time, min | Heating Rate up to 1800 °С, °С/min | Heating Rate from 1800 °С to 1900 °С, °С/min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPS 1521 | 1900 | 25 | 5 | 50 | 25 |

| SPS 1522 | 1900 | 50 | 5 | 50 | 25 |

| SPS 1523 | 1900 | 50 | 5 | 100 | 25 |

| Sample Number | W *, % | OP *, % | ρ *, g/cm3 | ρrel *, % | HV *, GPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPS 1521 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 3.224 ± 0.003 | 98.77 | 17.8 ± 1.7 |

| SPS 1522 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 3.256 ± 0.003 | 100 | 18.2 ± 1.2 |

| SPS 1523 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 3.257 ± 0.003 | 100 | 17.5 ± 0.7 |

| Sample Number | Capacitance, pF | Dielectric Constant | Loss Tangent | Resistivity, Ω⋅cm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPS 1521 | 20 | 52 | 0.700 | 4.9 × 104 |

| SPS 1522 | 31 | 79 | 1.730 | 1.3 × 104 |

| SPS 1523 | 6.5 | 17 | 0.002 | 3.5 × 107 |

| Composite | Additives | Method | T, °С | Conditions | Structure | R *, Ω⋅cm | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiC–50 mol%-AlN | 5 mol% Y2O3 | PL * | 2000 | Ar, 8 h | SS+SiC | 1018 | [29] |

| SiC–50 mol%-AlN | 5 mol% Y2O3 | PL * | 2000 | N2, 8 h | SS+SiC | 1017 | [29] |

| SiC–35 vol.%-AlN | - | HP * | 1950 | Ar, 2 h, 40 MPa | SS+SiC | 1.1 × 1010 | [37] |

| AlN–SiC | Y2O3 | PL * | 2000 | N2 | AlN+SiC | 105–109 ** | [5] |

| SiC–50 mol%-AlN | 0.2 wt.% B 1.0 wt.% C | HP * | 2100 | 1 h, 35 MPa | SS | 4.0 × 106 | [38] |

| SiC–50 mol%-AlN | - | SPS * | 1900–2100 | Ar, 30 min, 50 MPa | SS+SiC | 103 –105 | [21] |

| 35 vol.%-SiC–AlN | 4 wt.% Al2O3 + 2 wt.% Y2O3 | HP | 1900 | N2, 1.5 h, 25 MPa | AlN+SS+SiC | ~104 | [3] |

| SiC–30 wt.%-AlN | 5 wt.% Al2O3–Y2O3 | PL * | 2080 | Vacuum, 2 h | AlN+SS+SiC | 1.1 × 101 | [32] |

| SiC–50 mol%-AlN | - | PL * | 2000 | Ar, 1 h | SS | 3.3 × 101 | [36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smetyukhova, T.N.; Arbanas, L.; Sokolov, A.D.; Bazarova, V.E.; Pristinskiy, Y.; Smirnov, A.; Pinargote, N.W.S. Processing and Characterization of AlN–SiC Composites Obtained by Spark Plasma Sintering. Sci 2025, 7, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040174

Smetyukhova TN, Arbanas L, Sokolov AD, Bazarova VE, Pristinskiy Y, Smirnov A, Pinargote NWS. Processing and Characterization of AlN–SiC Composites Obtained by Spark Plasma Sintering. Sci. 2025; 7(4):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040174

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmetyukhova, Tatiana N., Levko Arbanas, Anton D. Sokolov, Viktoria E. Bazarova, Yuri Pristinskiy, Anton Smirnov, and Nestor Washington Solis Pinargote. 2025. "Processing and Characterization of AlN–SiC Composites Obtained by Spark Plasma Sintering" Sci 7, no. 4: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040174

APA StyleSmetyukhova, T. N., Arbanas, L., Sokolov, A. D., Bazarova, V. E., Pristinskiy, Y., Smirnov, A., & Pinargote, N. W. S. (2025). Processing and Characterization of AlN–SiC Composites Obtained by Spark Plasma Sintering. Sci, 7(4), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040174