Author Contributions

R.P.: writing—original draft, methodology, investigation, visualization, conceptualization, formal analysis, and data curation. S.M.: writing—review and editing, resources, methodology, investigation, visualization, conceptualization, project administration, and funding acquisition. N.M.: resources, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, and data curation. S.L.-A.: writing—review and editing, resources, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, validation, and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

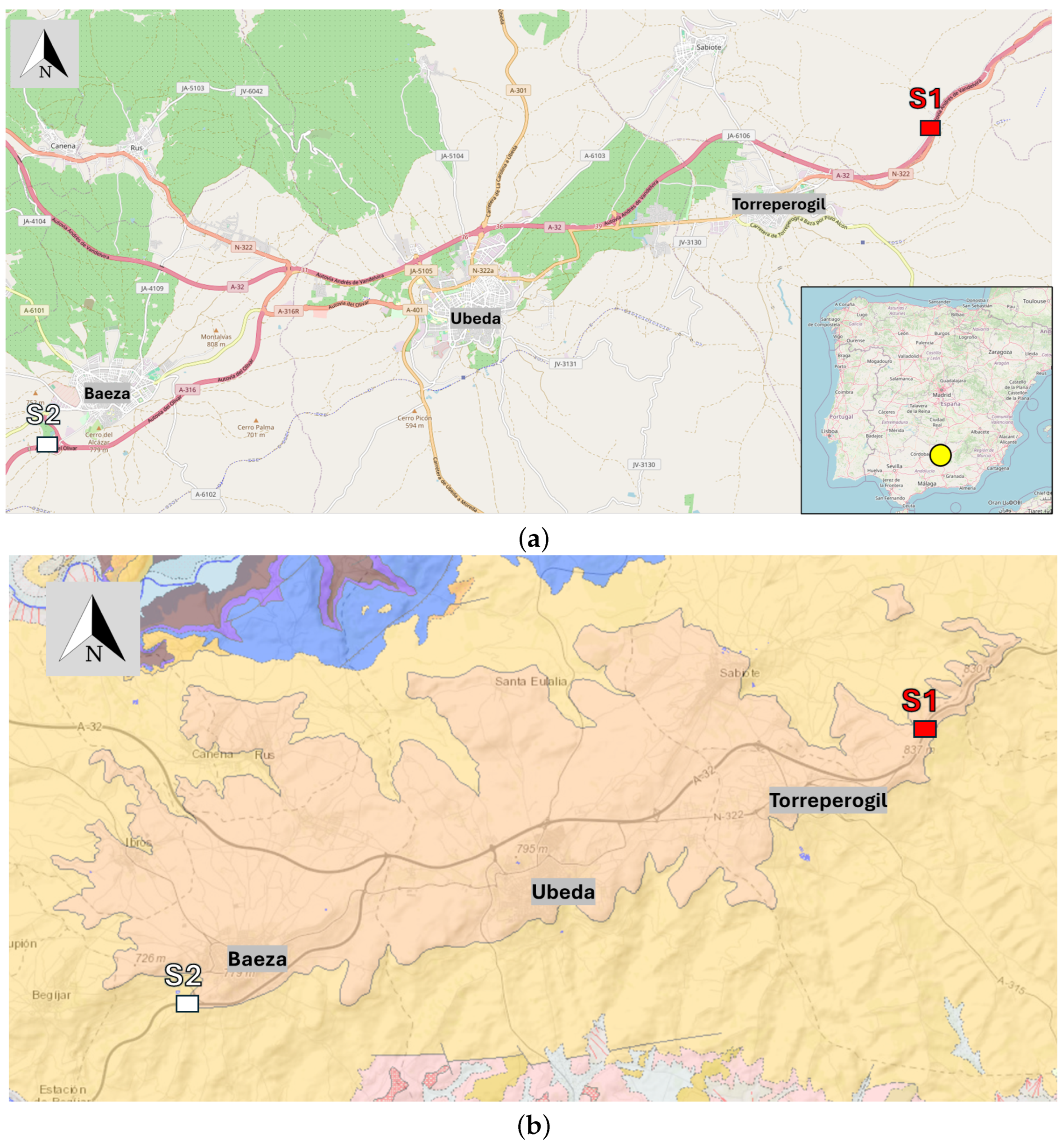

Figure 1.

(

a) Location of samples S1 (red) and S2 (white), yellow circle indicating the location of samples S1 and S2 within the geographical context of the map of Spain, modified using data from OpenStreetMap contributors. OpenStreetMap. Available online:

https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=13/38.01321/-3.36765 (accessed on 28 November 2025), (

b) Location on the IGME 2022 [

26] geological map, showing samples S1 (red) and S2 (white).

Figure 1.

(

a) Location of samples S1 (red) and S2 (white), yellow circle indicating the location of samples S1 and S2 within the geographical context of the map of Spain, modified using data from OpenStreetMap contributors. OpenStreetMap. Available online:

https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=13/38.01321/-3.36765 (accessed on 28 November 2025), (

b) Location on the IGME 2022 [

26] geological map, showing samples S1 (red) and S2 (white).

Figure 2.

Example of nomenclature for SV20C5 (α = 20; β = 5) and SV0C5 (δ = 5).

Figure 2.

Example of nomenclature for SV20C5 (α = 20; β = 5) and SV0C5 (δ = 5).

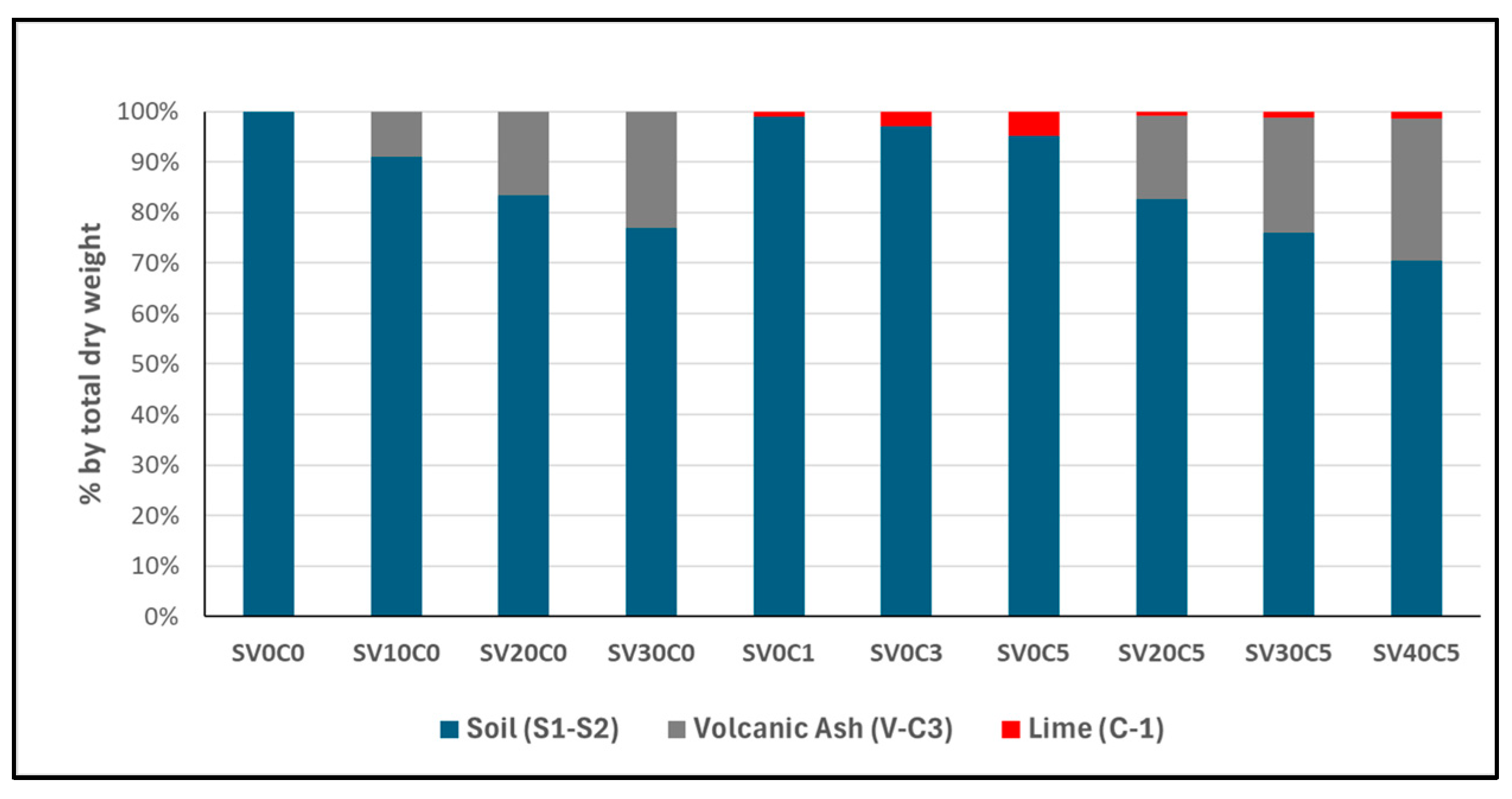

Figure 3.

Relative proportions of base soil, V-C3, and C-1 in soil mixtures on a total dry weight basis of the sample.

Figure 3.

Relative proportions of base soil, V-C3, and C-1 in soil mixtures on a total dry weight basis of the sample.

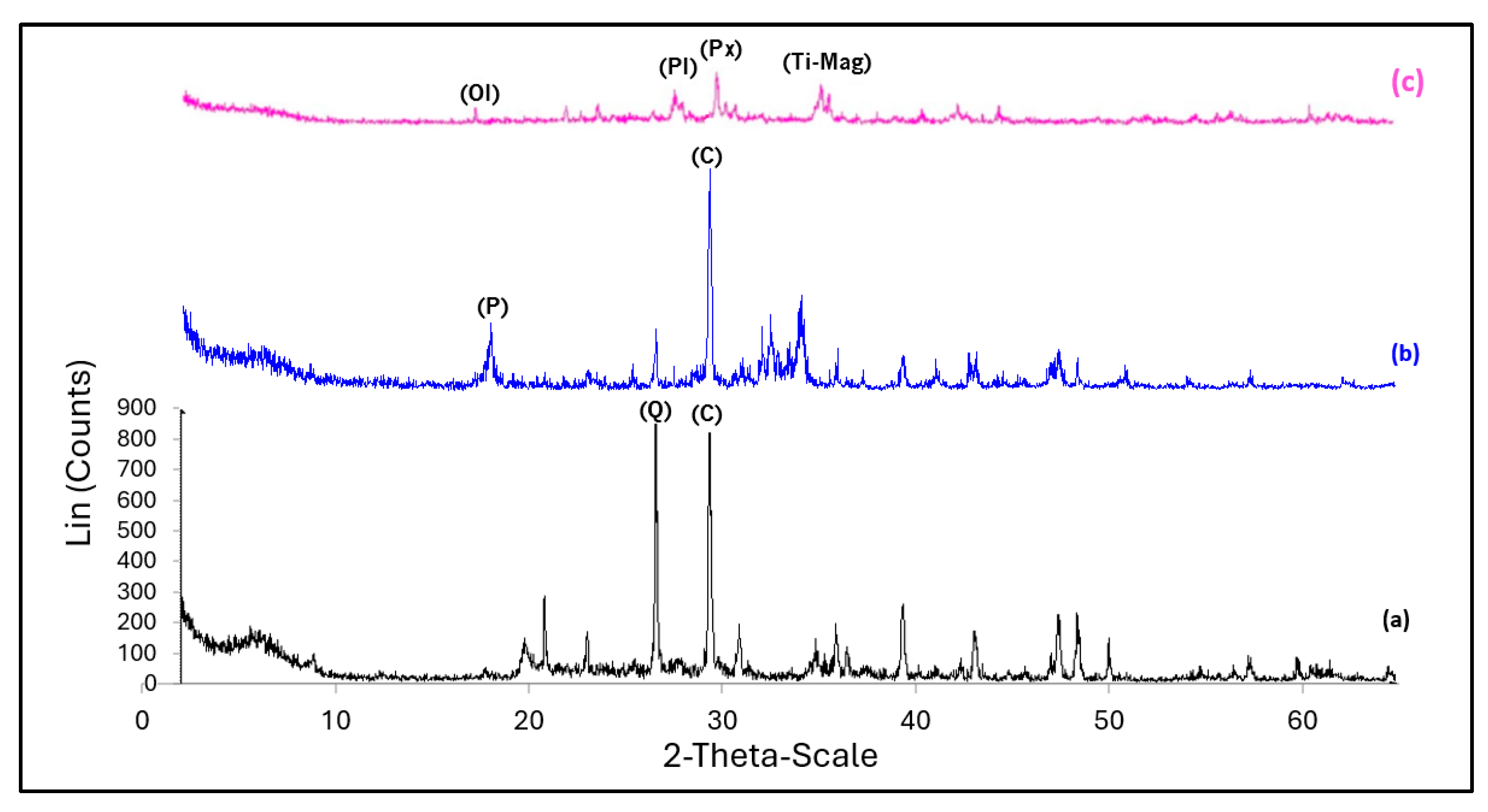

Figure 4.

Diffractogram and analysis for (a) S1 (SV0C0), (b) lime C-1, and (c) volcanic ash V-C3. (Q) quartz, (C) calcite, (P) portlandite, (Ol) olivine, (Px) pyroxene, (Pl) plagioclase, (Ti-Mag) Ti-magnetite.

Figure 4.

Diffractogram and analysis for (a) S1 (SV0C0), (b) lime C-1, and (c) volcanic ash V-C3. (Q) quartz, (C) calcite, (P) portlandite, (Ol) olivine, (Px) pyroxene, (Pl) plagioclase, (Ti-Mag) Ti-magnetite.

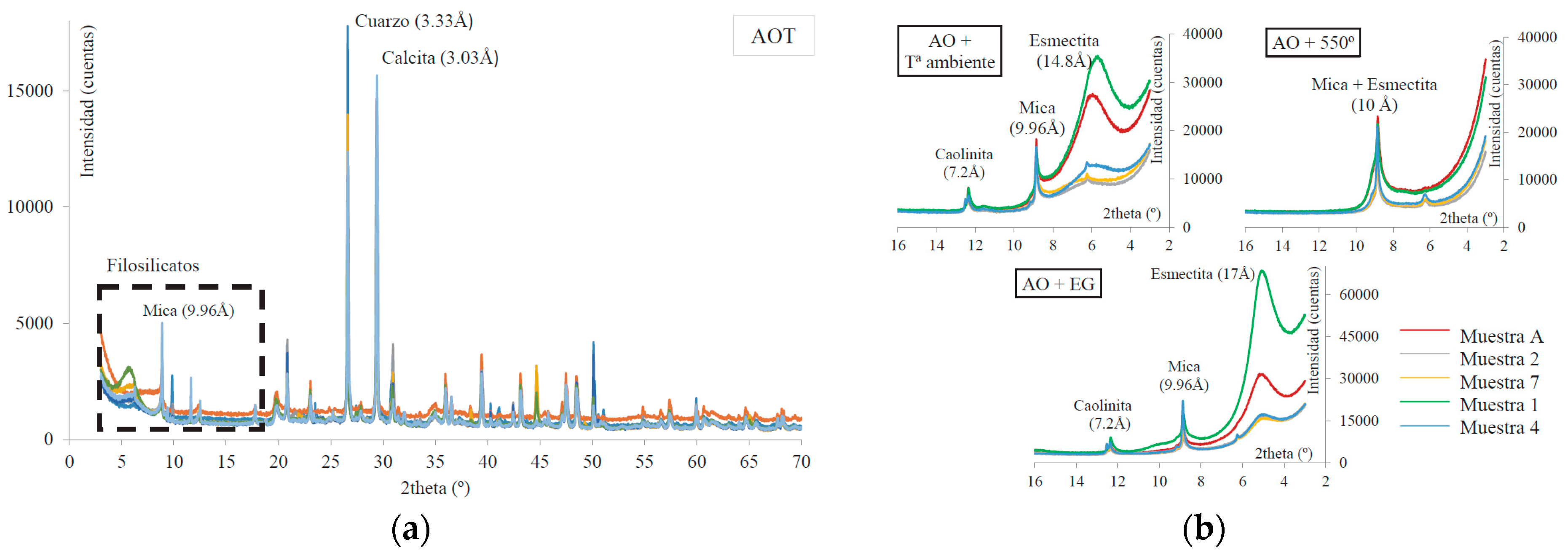

Figure 5.

(

a) Diffractograms of the analyzed sample of base soil S1 and (

b) results of the oriented aggregate technique (Montero and Estaire [

25]).

Figure 5.

(

a) Diffractograms of the analyzed sample of base soil S1 and (

b) results of the oriented aggregate technique (Montero and Estaire [

25]).

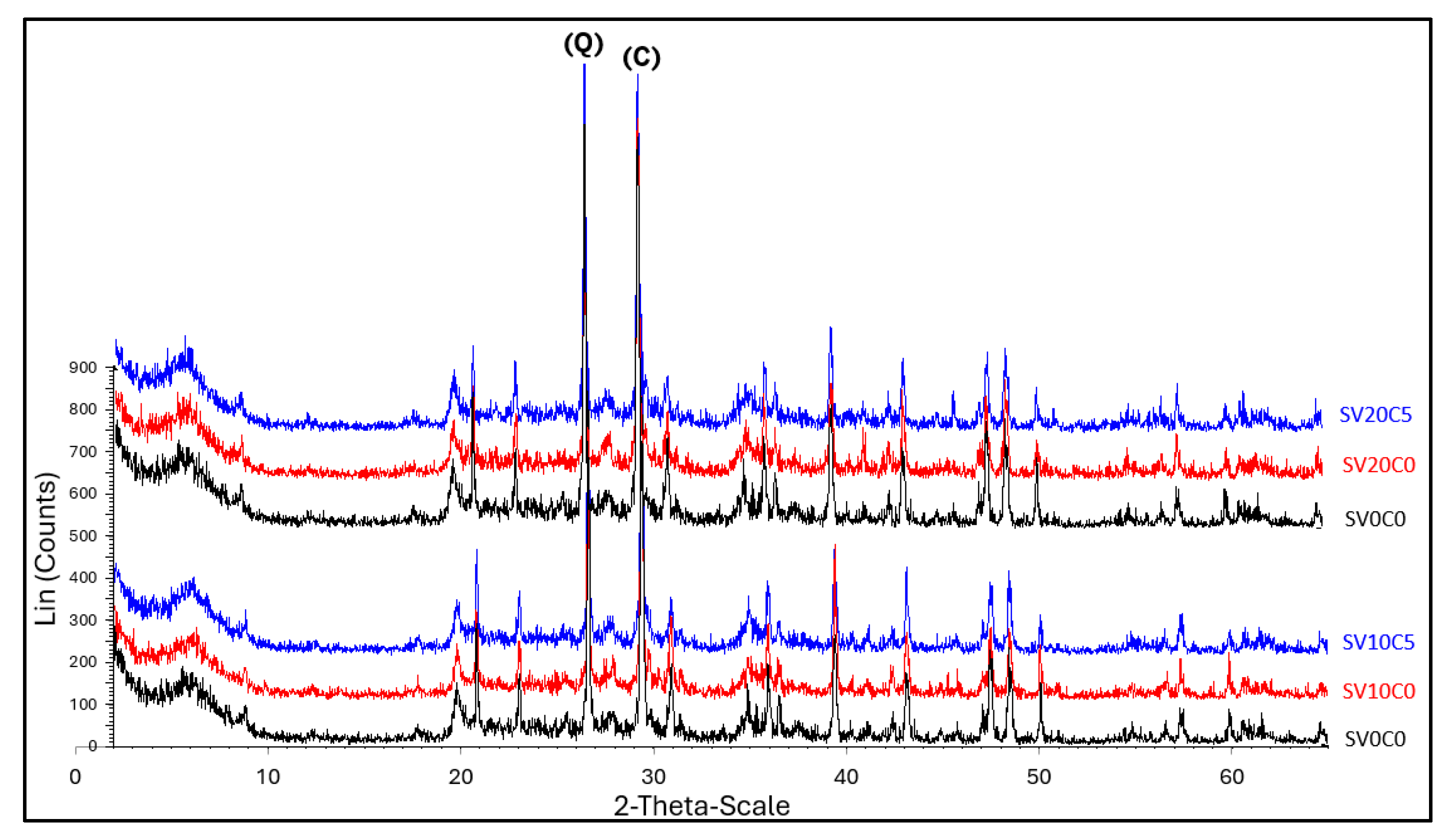

Figure 6.

Diffractograms of S1 (SV0C0) and soil mixtures SV10C0-SV10C5 and SV20C0–SV20C5. (Q) quartz, (C) calcite.

Figure 6.

Diffractograms of S1 (SV0C0) and soil mixtures SV10C0-SV10C5 and SV20C0–SV20C5. (Q) quartz, (C) calcite.

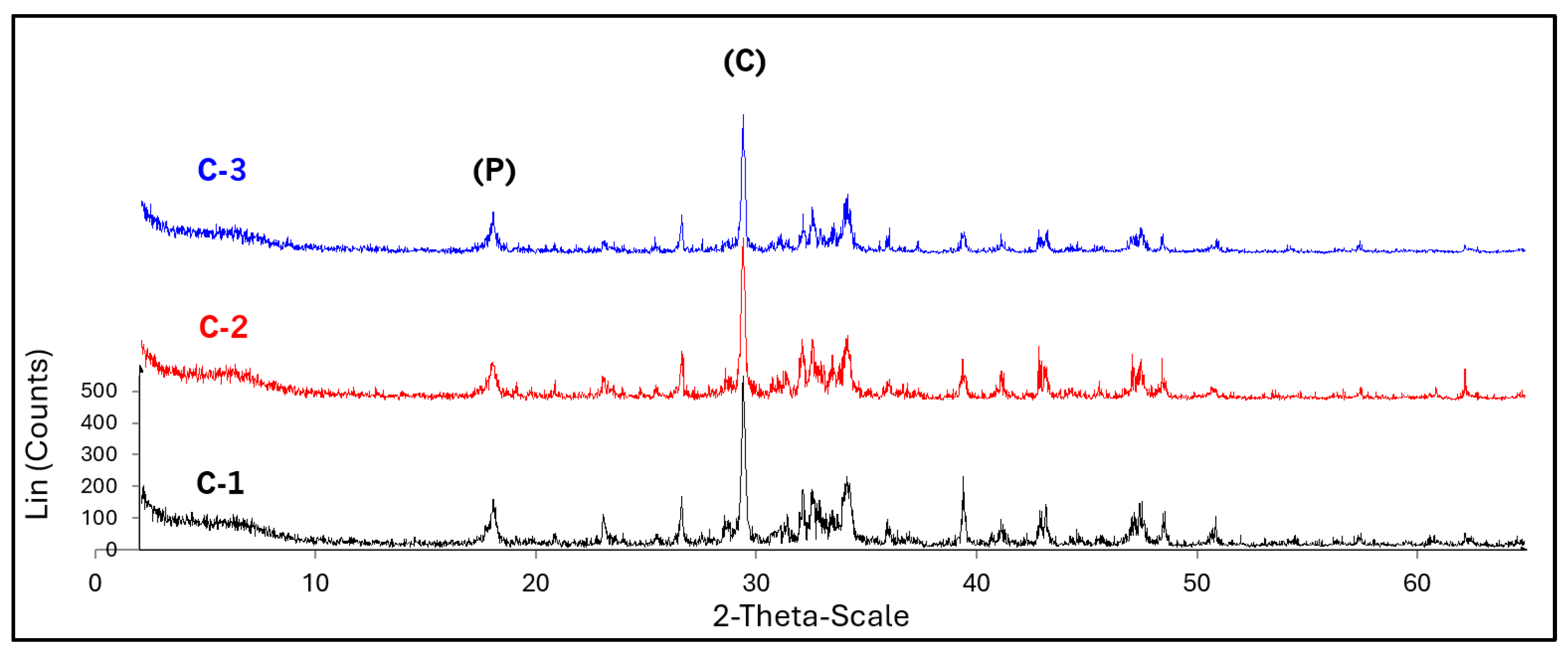

Figure 7.

Diffractograms of lime C-1, C-2, and C-3; (P) portlandite, (C) calcite.

Figure 7.

Diffractograms of lime C-1, C-2, and C-3; (P) portlandite, (C) calcite.

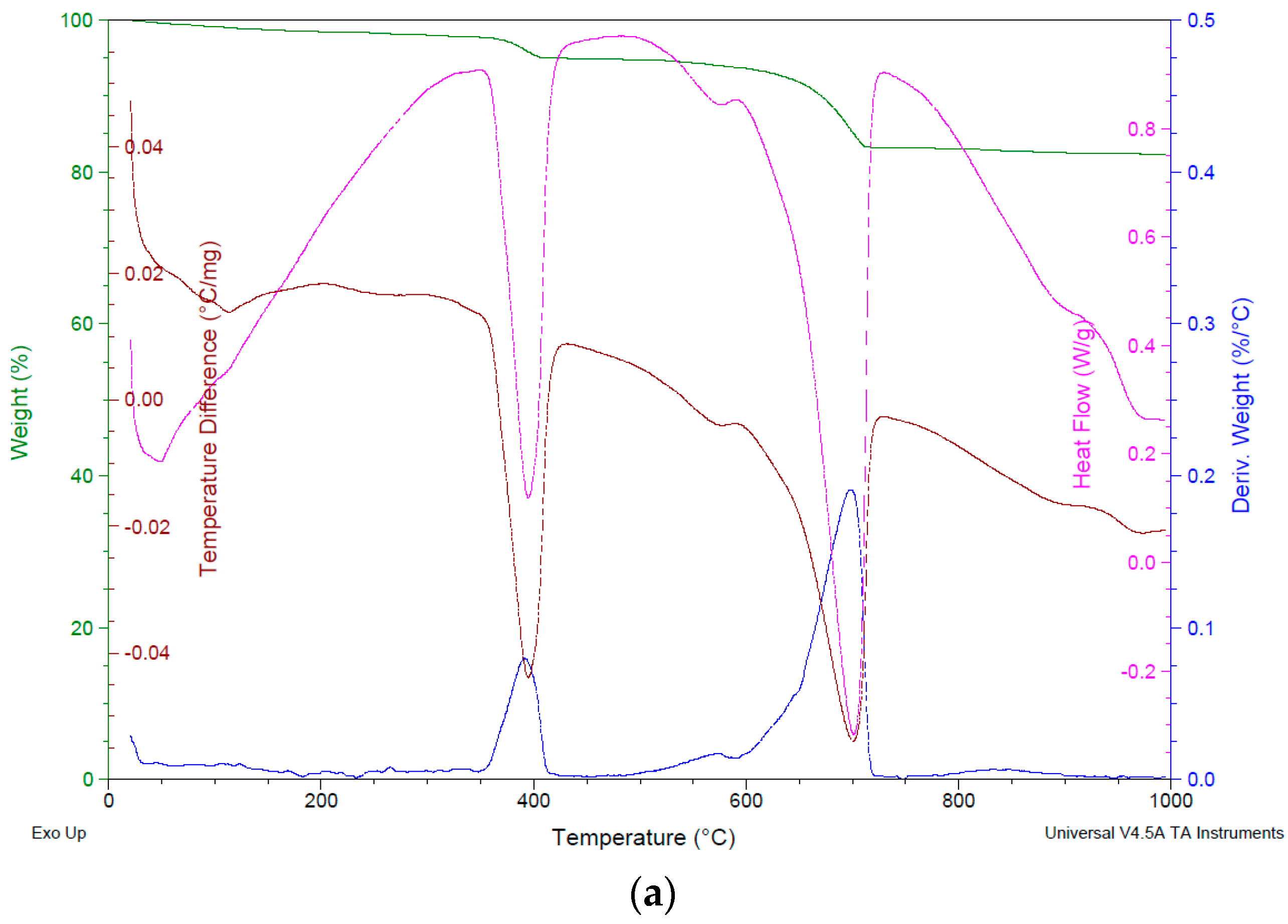

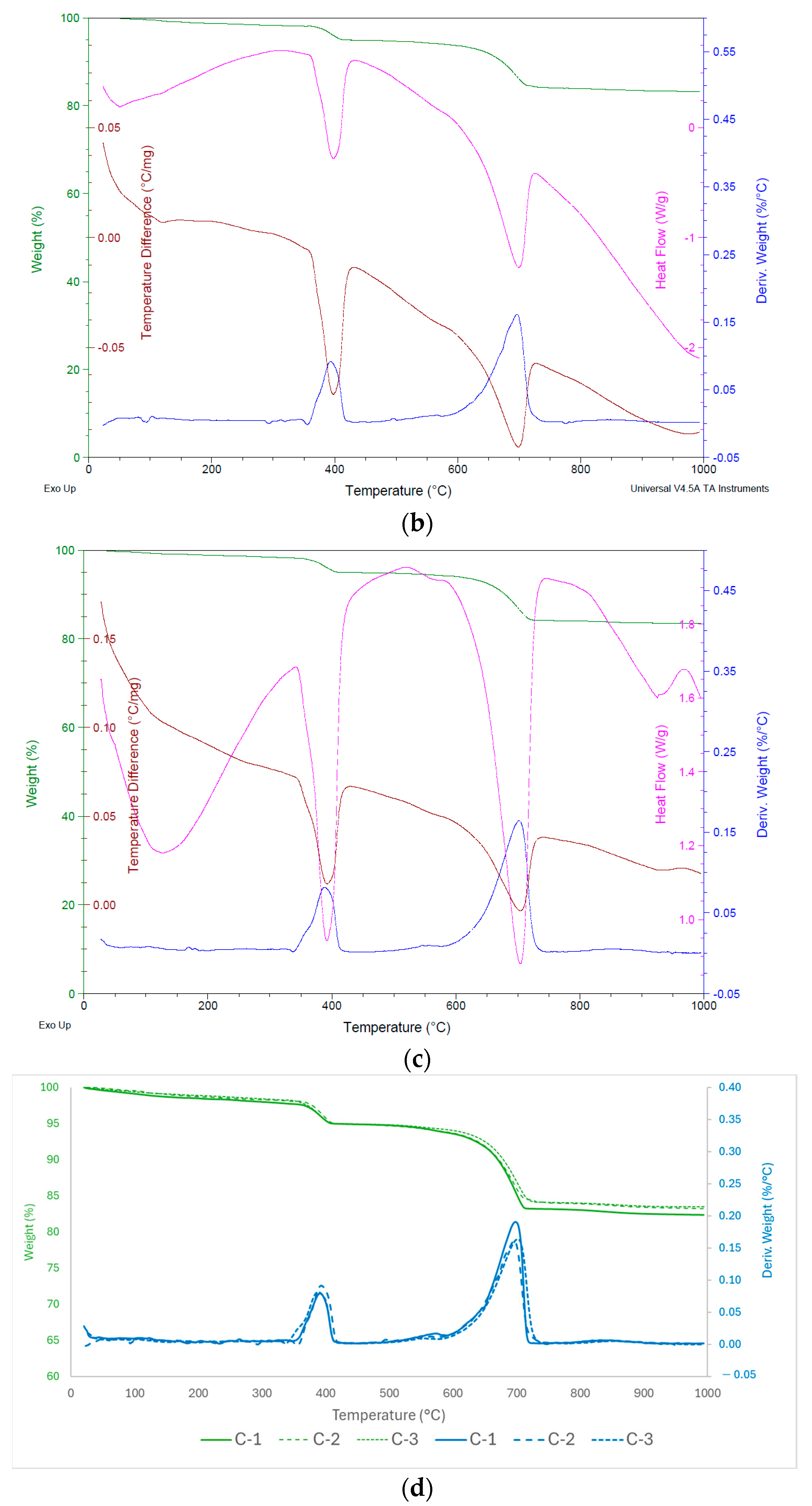

Figure 8.

General results of (a) TGA-C-1, (b) TGA-C-2, and (c) TGA-C-3 and (d) comparative TGA graphic.

Figure 8.

General results of (a) TGA-C-1, (b) TGA-C-2, and (c) TGA-C-3 and (d) comparative TGA graphic.

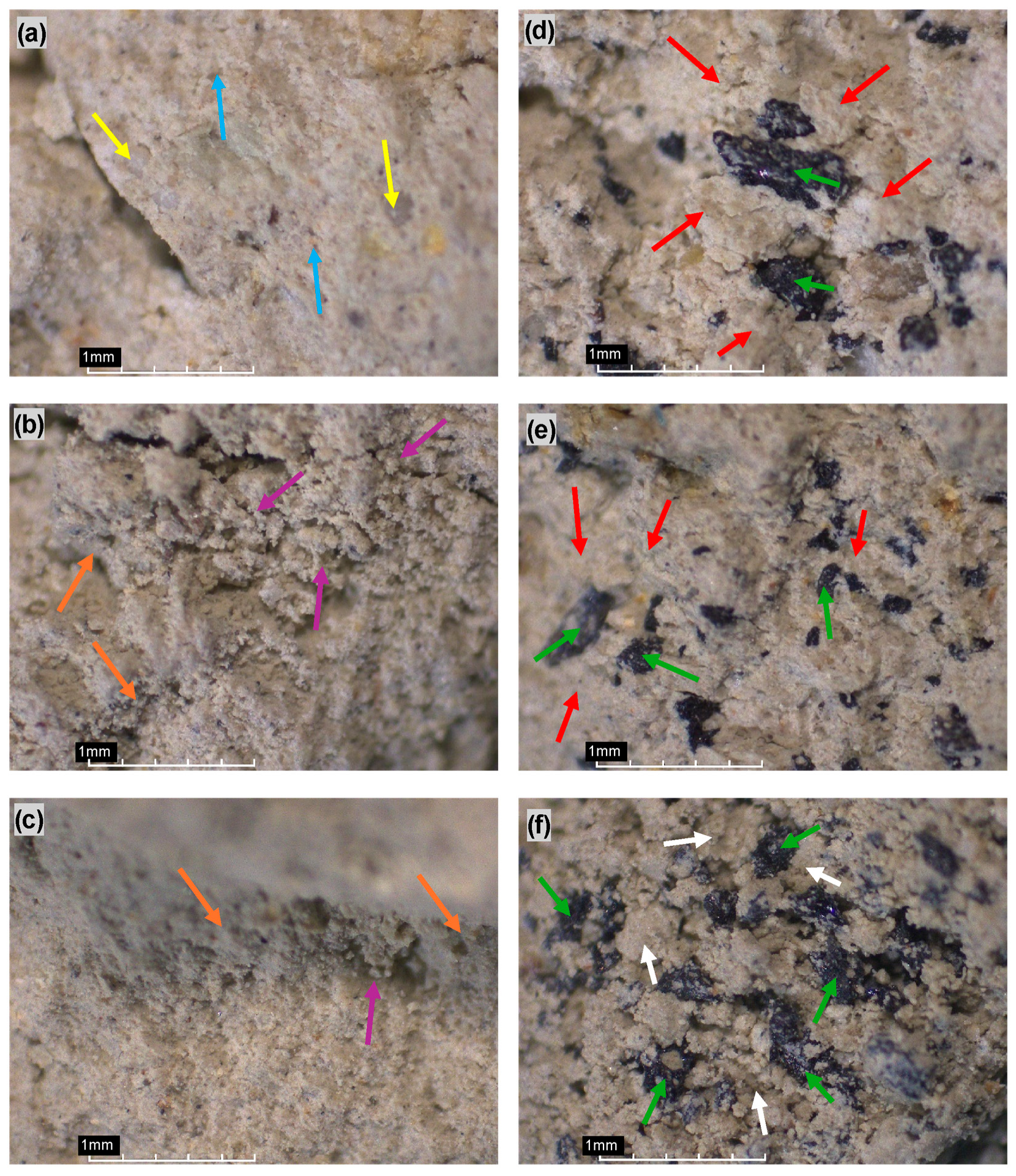

Figure 9.

Optical images with 40X magnification maximum range: (a) SV0C0, (b) SV0C3, (c) SV0C5, (d) SV20C5, (e) SV30C5, and (f) SV30C0. Arrows, green—volcanic ash particles V-C3; yellow—quartz; light blue—smooth surface, plastic clay; red—cemented structure (C-S-H/C-A-H) around volcanic ash particles V-C3; magenta—flocculation of grains; white—dispersed material around volcanic ashes; orange—C-S-H gel.

Figure 9.

Optical images with 40X magnification maximum range: (a) SV0C0, (b) SV0C3, (c) SV0C5, (d) SV20C5, (e) SV30C5, and (f) SV30C0. Arrows, green—volcanic ash particles V-C3; yellow—quartz; light blue—smooth surface, plastic clay; red—cemented structure (C-S-H/C-A-H) around volcanic ash particles V-C3; magenta—flocculation of grains; white—dispersed material around volcanic ashes; orange—C-S-H gel.

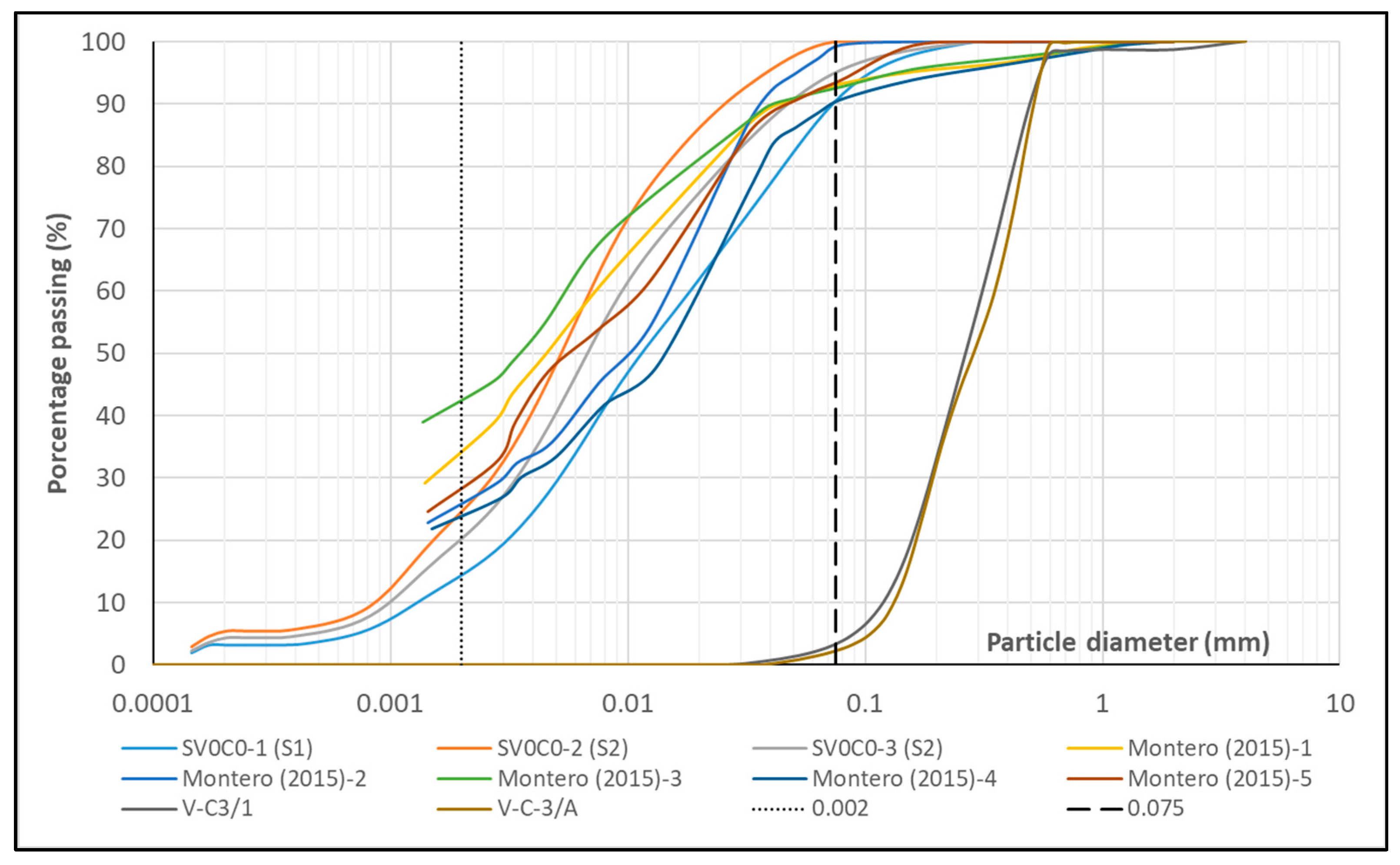

Figure 10.

Grain size distribution of SV0C0, V-C3, and reference soil samples.

Figure 10.

Grain size distribution of SV0C0, V-C3, and reference soil samples.

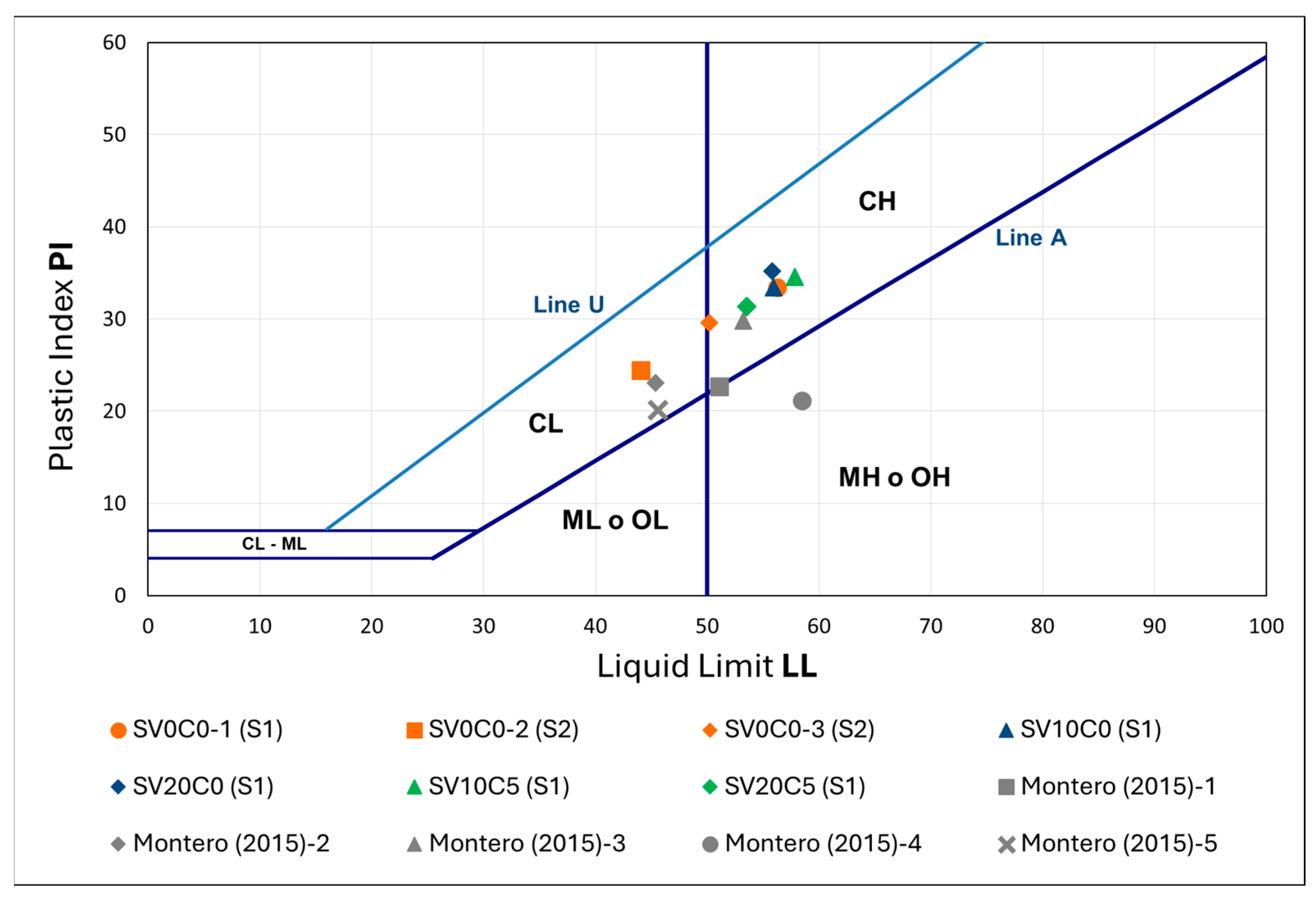

Figure 11.

Plasticity chart of S1, S2, soil mixtures, and reference soil.

Figure 11.

Plasticity chart of S1, S2, soil mixtures, and reference soil.

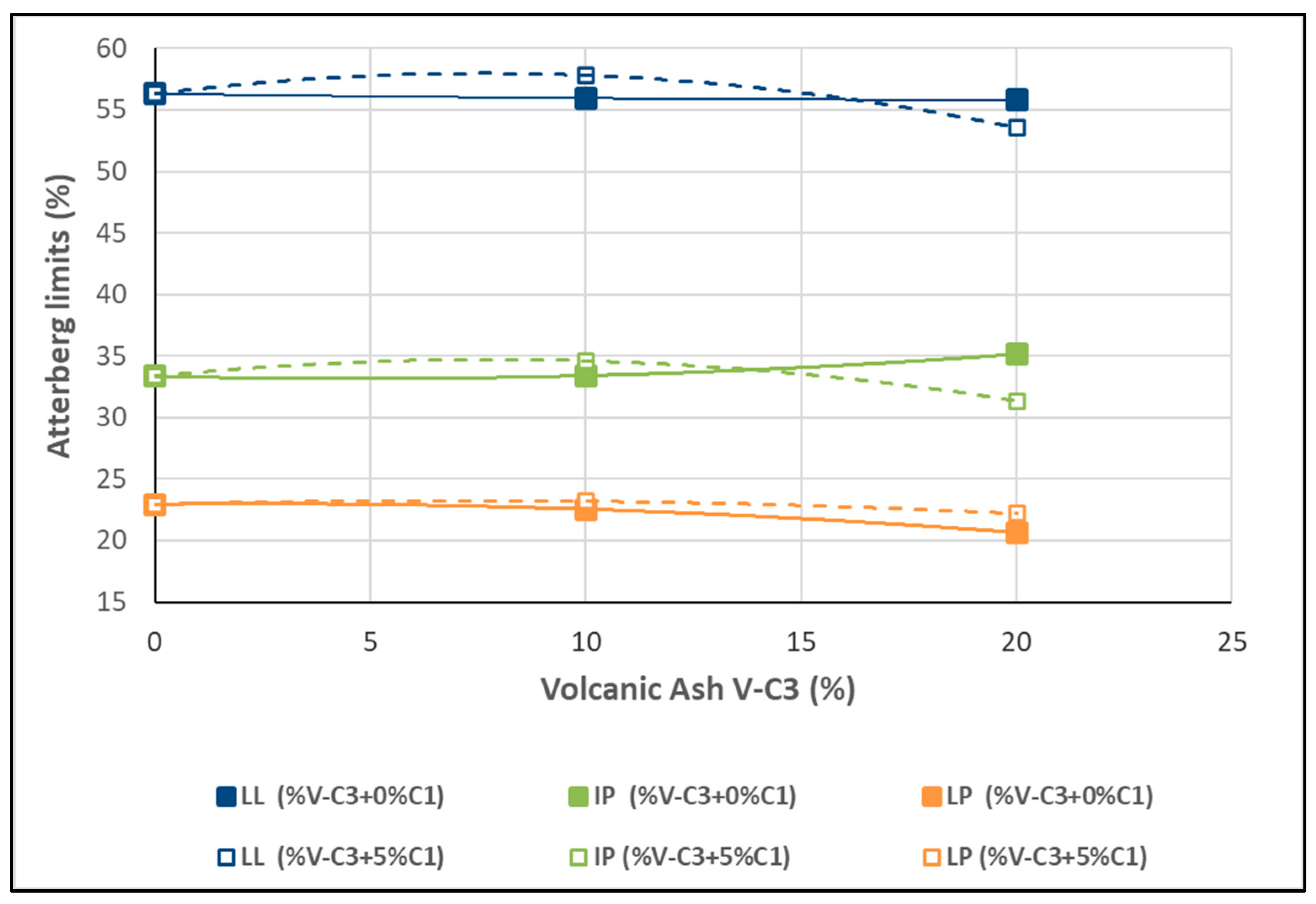

Figure 12.

Variation in LL and PI as a function of the variation in V-C3 with the addition of C-1 at 0% and 5%.

Figure 12.

Variation in LL and PI as a function of the variation in V-C3 with the addition of C-1 at 0% and 5%.

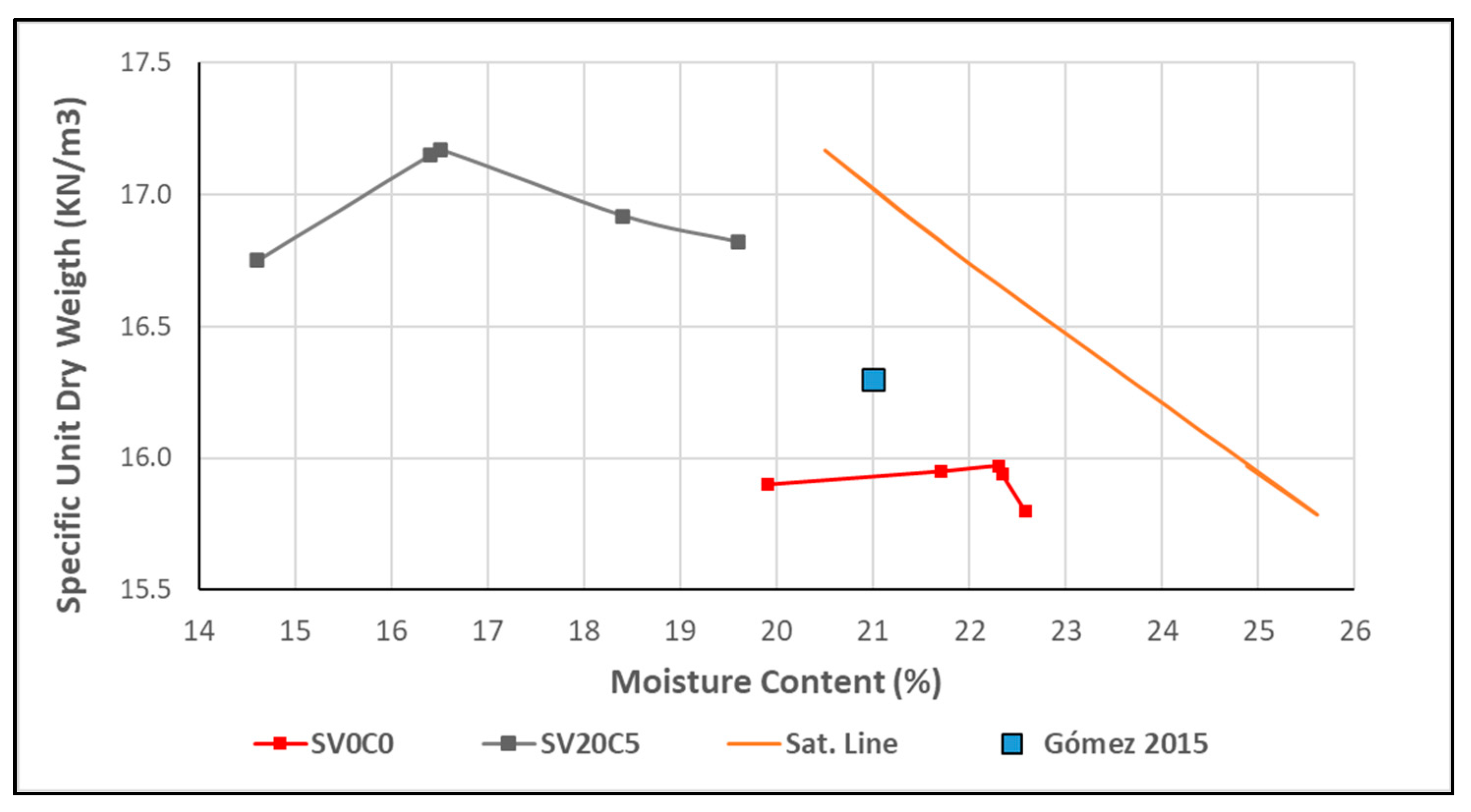

Figure 13.

Compaction curve of soil SV0C0 (S1), soil mixture SV20C5, and reference soil.

Figure 13.

Compaction curve of soil SV0C0 (S1), soil mixture SV20C5, and reference soil.

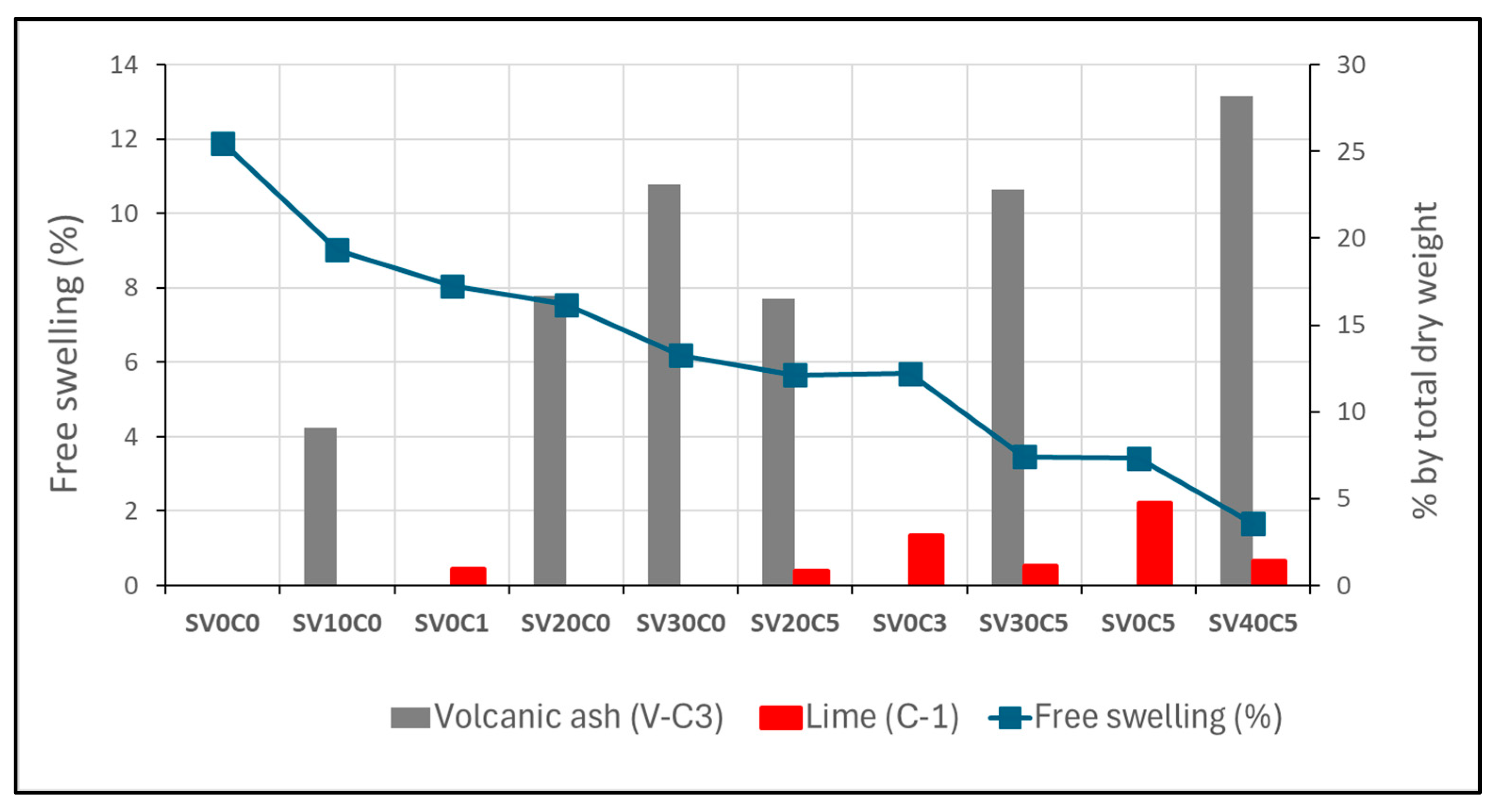

Figure 14.

Free swelling test curve for soil and soil mixtures.

Figure 14.

Free swelling test curve for soil and soil mixtures.

Figure 15.

Evolution of free swelling for different soil mixtures, indicating V-C3 and C-1 percentages relative to total dry weight.

Figure 15.

Evolution of free swelling for different soil mixtures, indicating V-C3 and C-1 percentages relative to total dry weight.

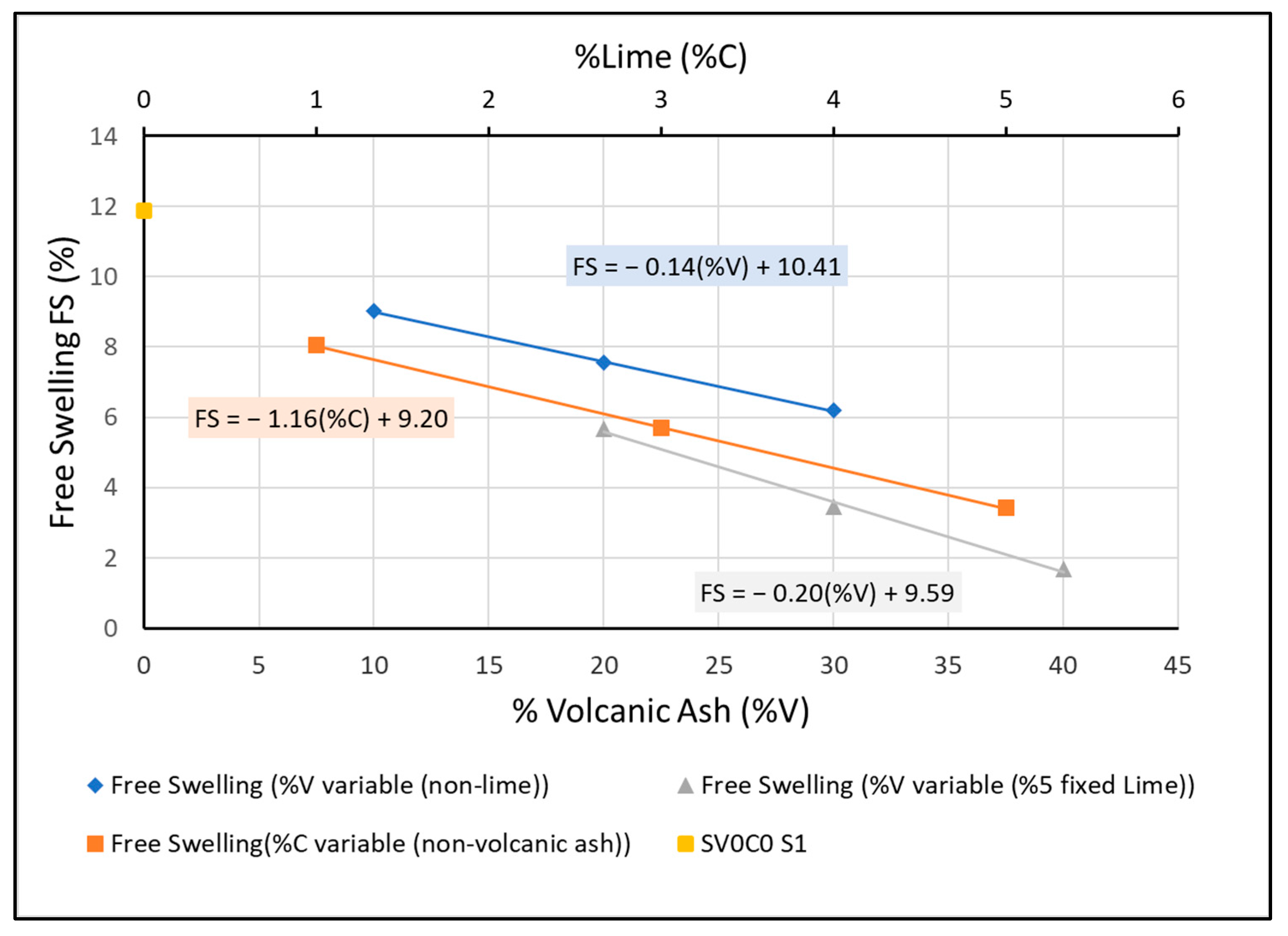

Figure 16.

Free swelling percentages of mixtures with volcanic ash without lime, volcanic ash with 5% lime added, and only lime.

Figure 16.

Free swelling percentages of mixtures with volcanic ash without lime, volcanic ash with 5% lime added, and only lime.

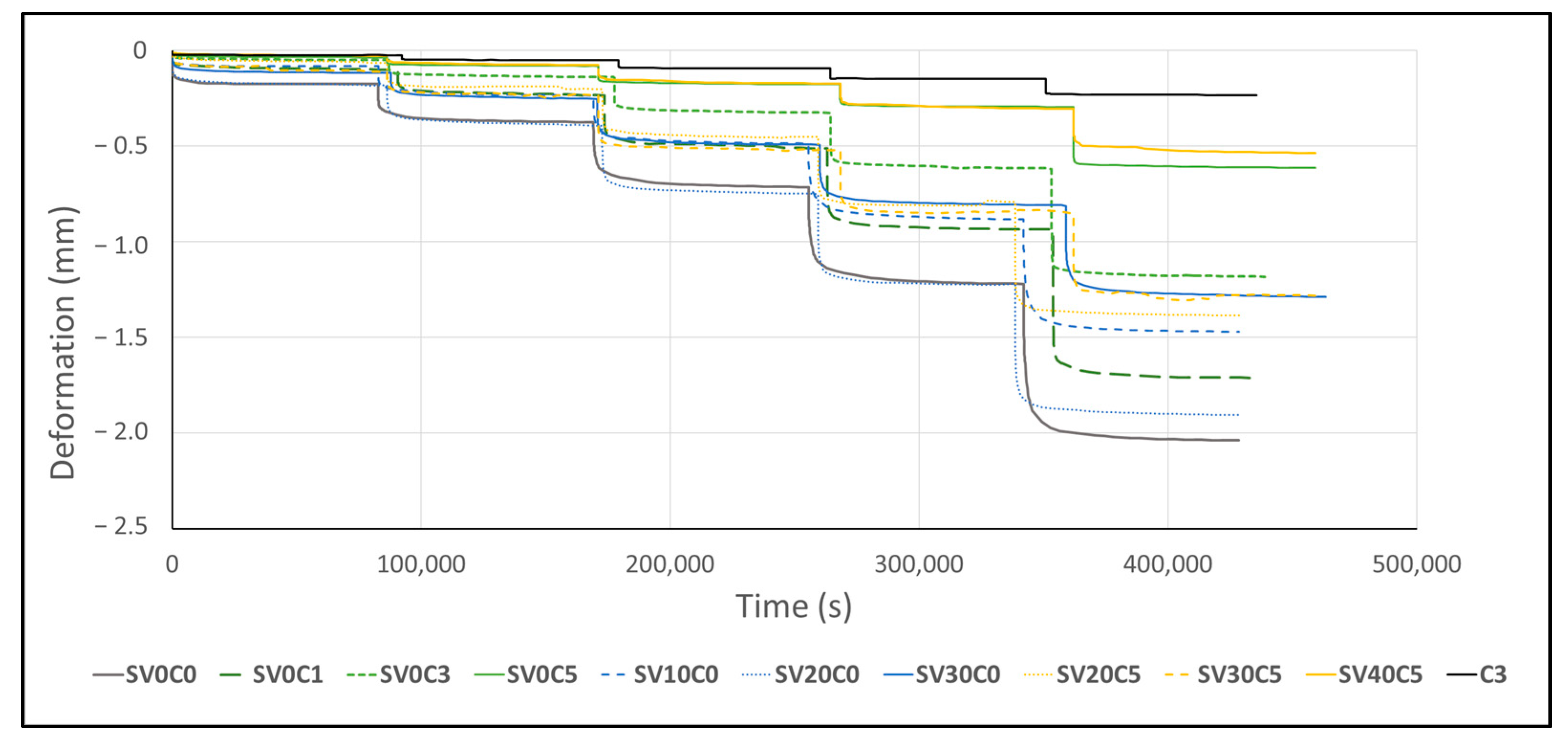

Figure 17.

Vertical deformation relationship over time under applied vertical loads.

Figure 17.

Vertical deformation relationship over time under applied vertical loads.

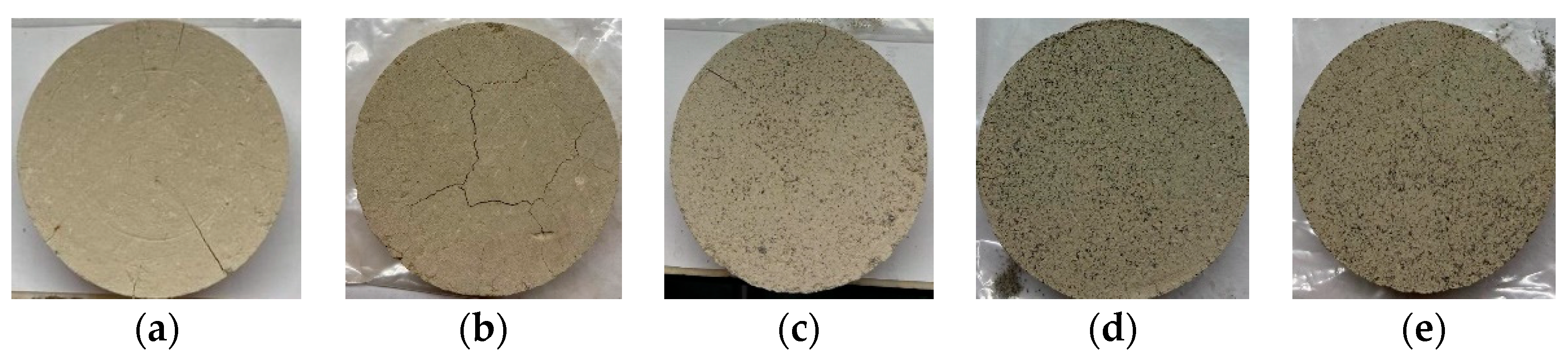

Figure 18.

Visual appearance of representative samples (a) SV0C0, (b) SV0C5, (c) SV20C5, (d) SV30C5, and (e) SV40C5.

Figure 18.

Visual appearance of representative samples (a) SV0C0, (b) SV0C5, (c) SV20C5, (d) SV30C5, and (e) SV40C5.

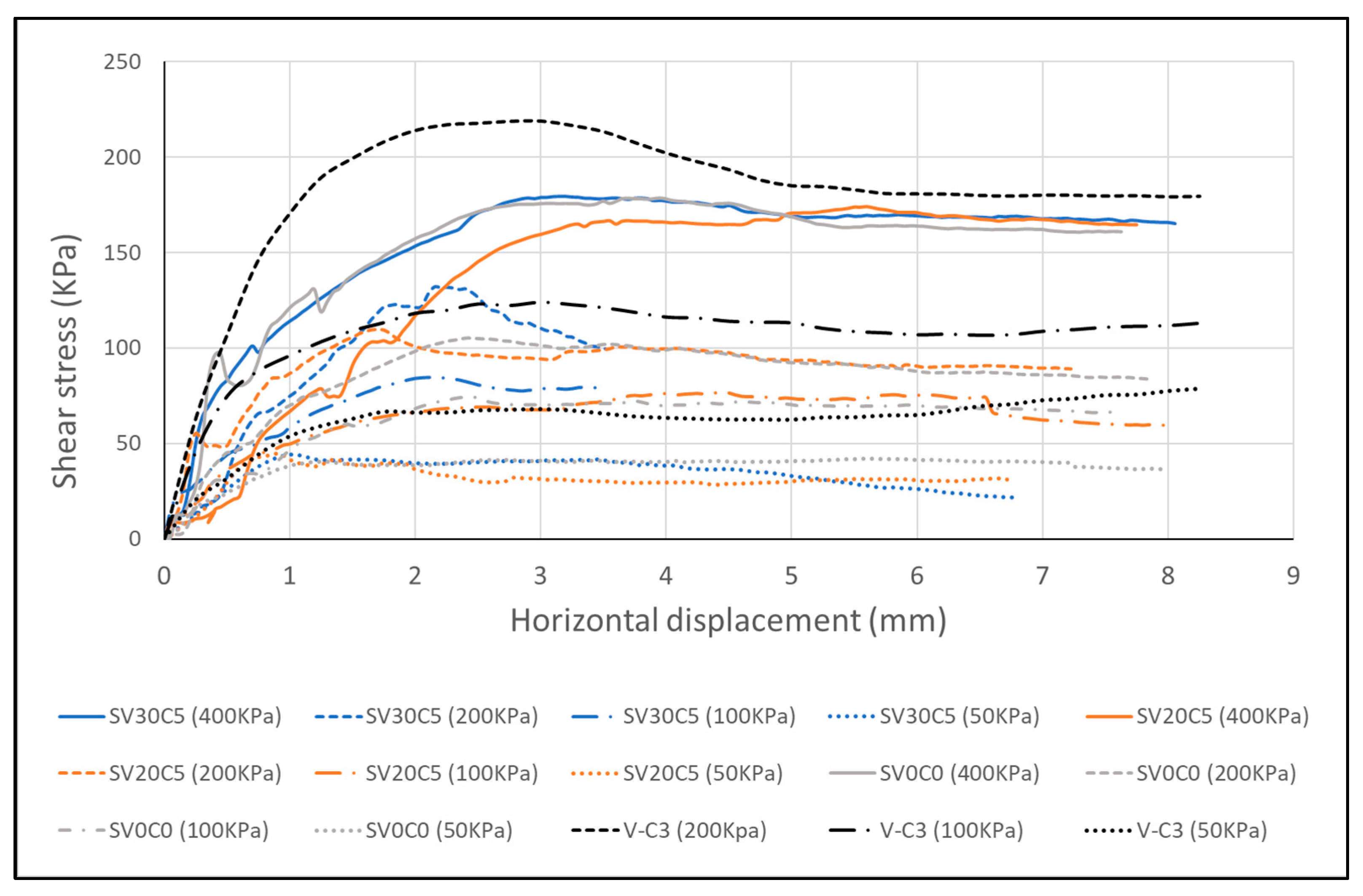

Figure 19.

Shear strength–displacement response of base soil SV0C0 (S2), volcanic ash (V-C3), and soil mixtures.

Figure 19.

Shear strength–displacement response of base soil SV0C0 (S2), volcanic ash (V-C3), and soil mixtures.

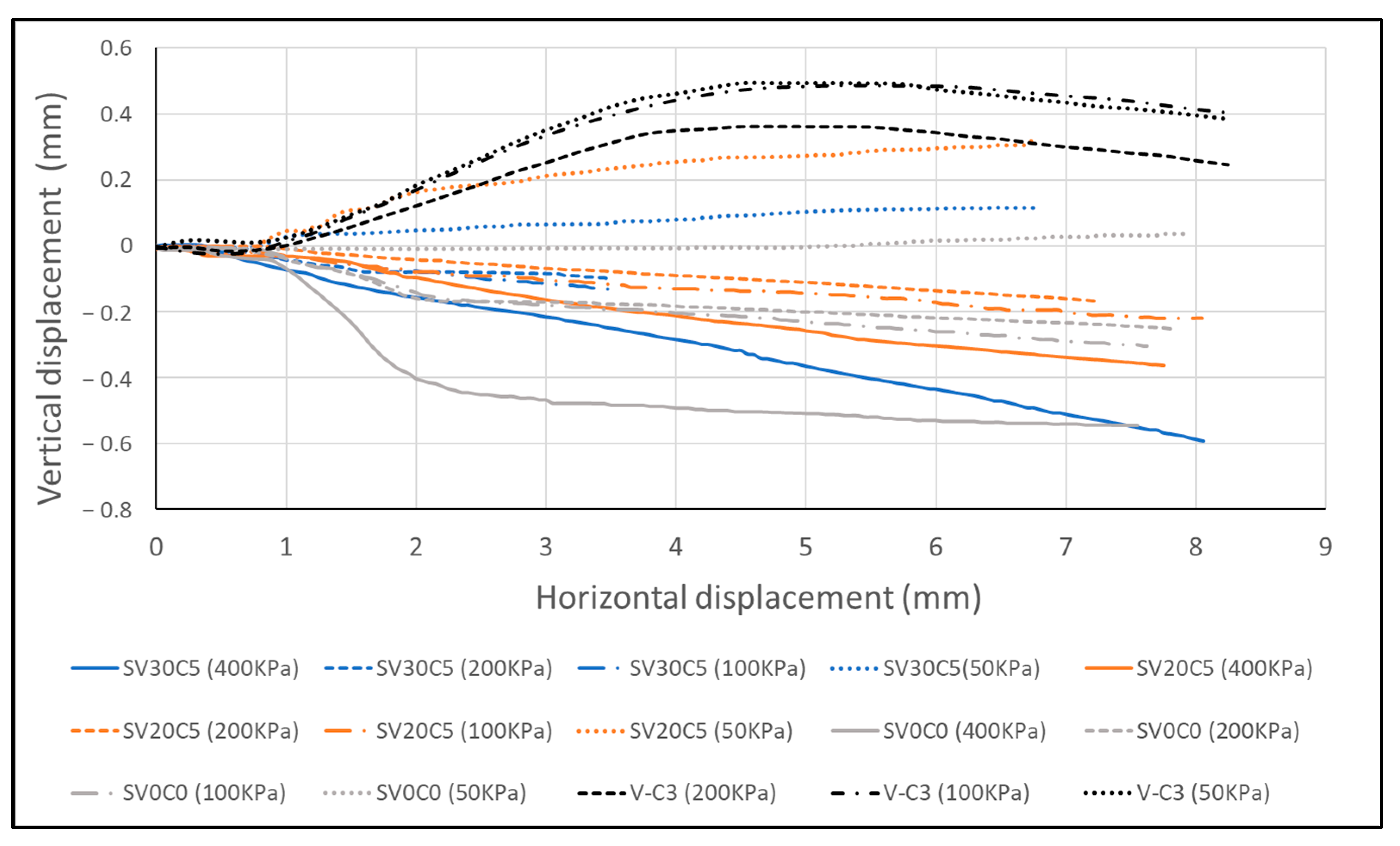

Figure 20.

Vertical–horizontal displacement response of base soil SV0C0 (S2), volcanic ash (V-C3), and soil mixtures.

Figure 20.

Vertical–horizontal displacement response of base soil SV0C0 (S2), volcanic ash (V-C3), and soil mixtures.

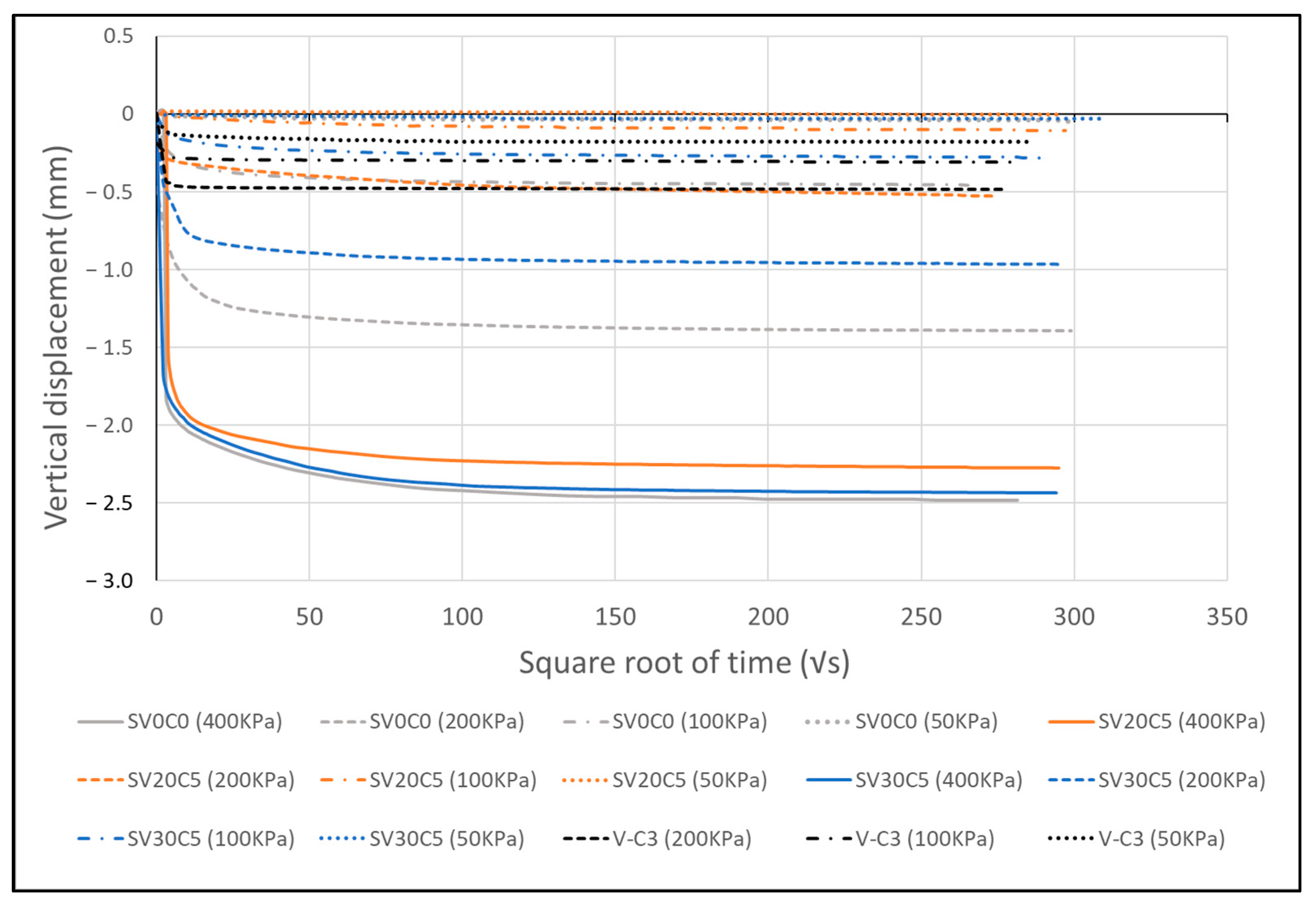

Figure 21.

Vertical deformation–square root of time response during the consolidation stage of the direct shear test.

Figure 21.

Vertical deformation–square root of time response during the consolidation stage of the direct shear test.

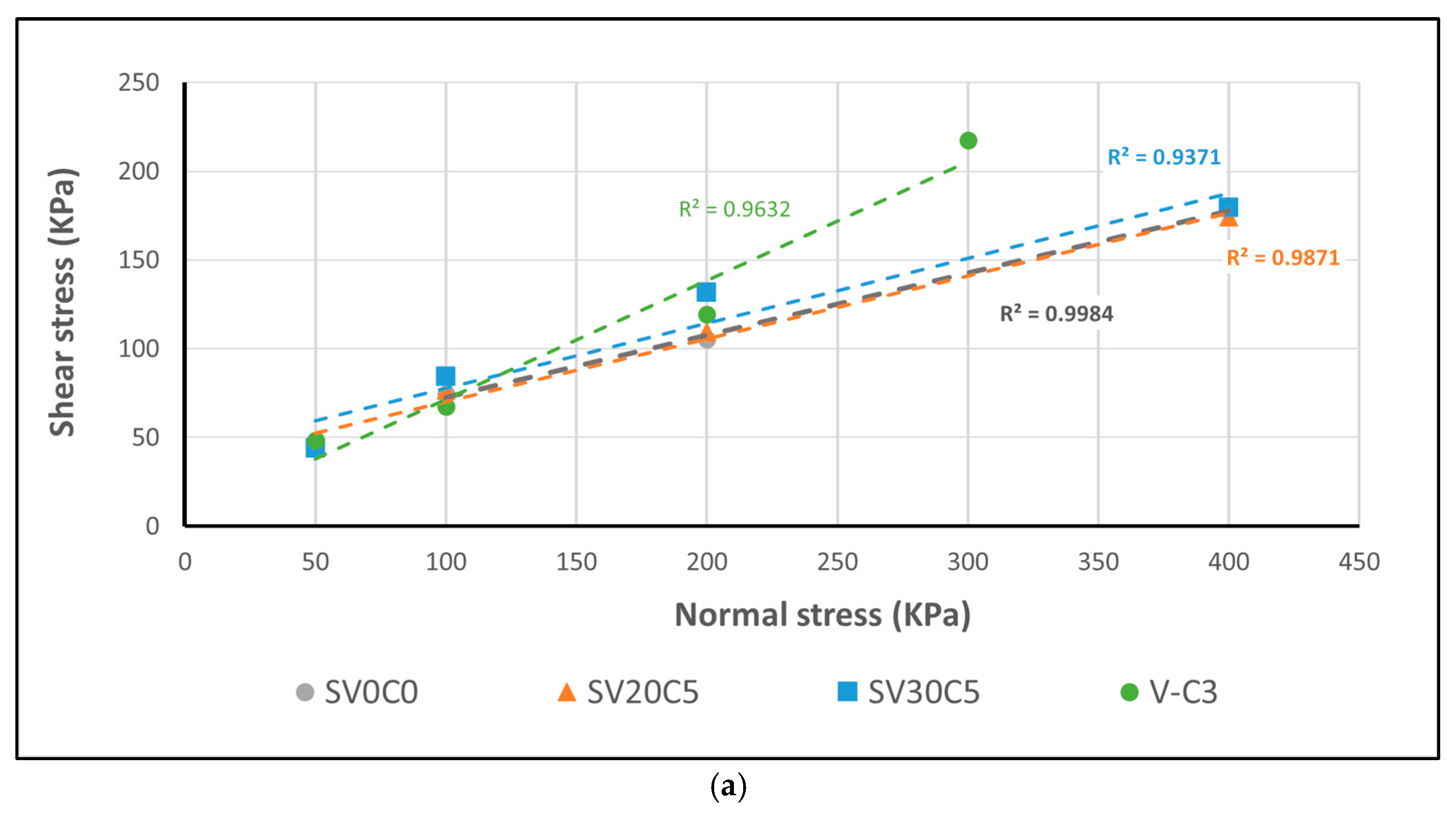

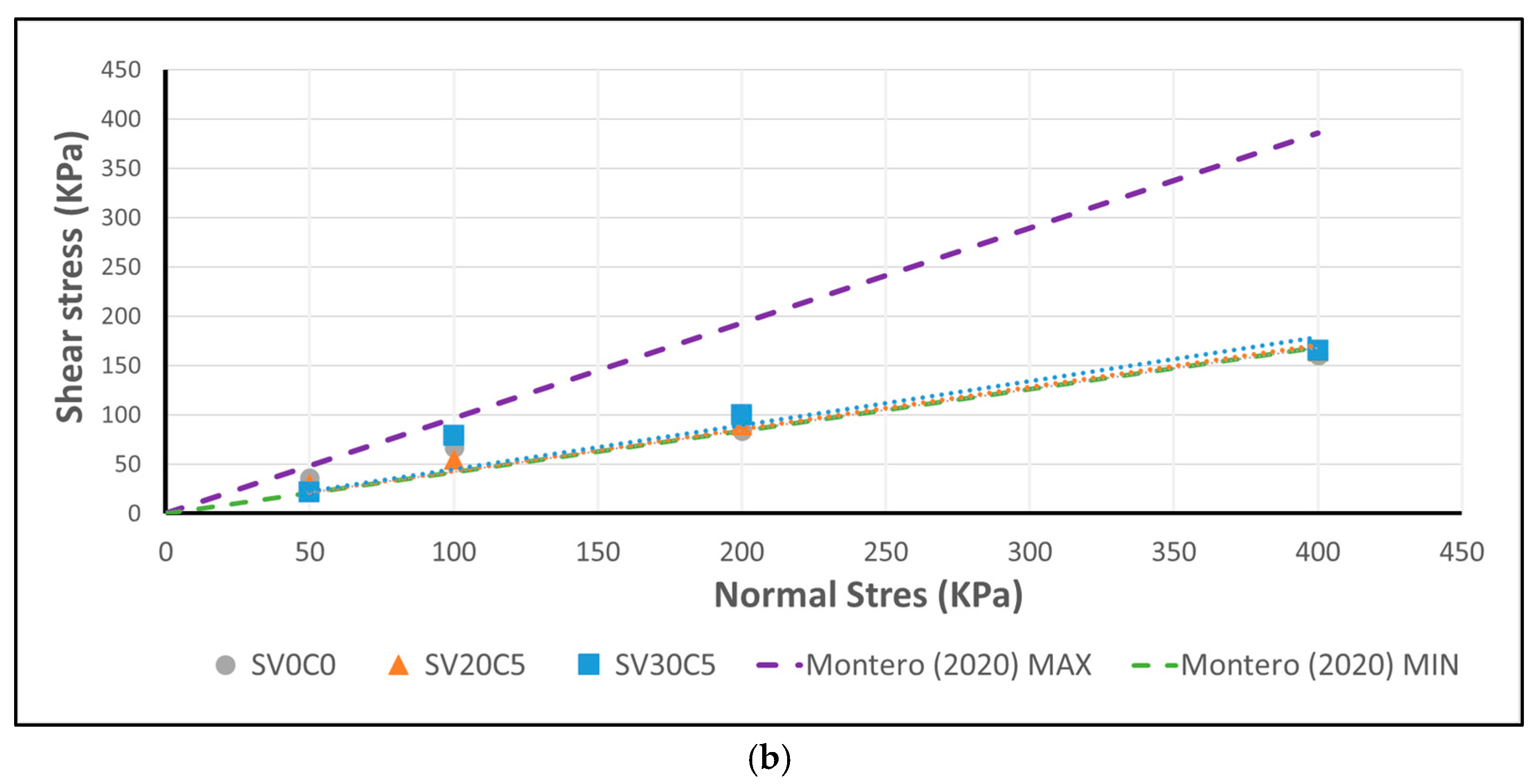

Figure 22.

(

a) Correlation between shear and normal stress for peak shear strength. (

b) Residual strength envelopes of base soil SV0C0 (S2) and mixtures SV20C5 and SV30C5, compared with the results reported by Montero and Estaire [

25].

Figure 22.

(

a) Correlation between shear and normal stress for peak shear strength. (

b) Residual strength envelopes of base soil SV0C0 (S2) and mixtures SV20C5 and SV30C5, compared with the results reported by Montero and Estaire [

25].

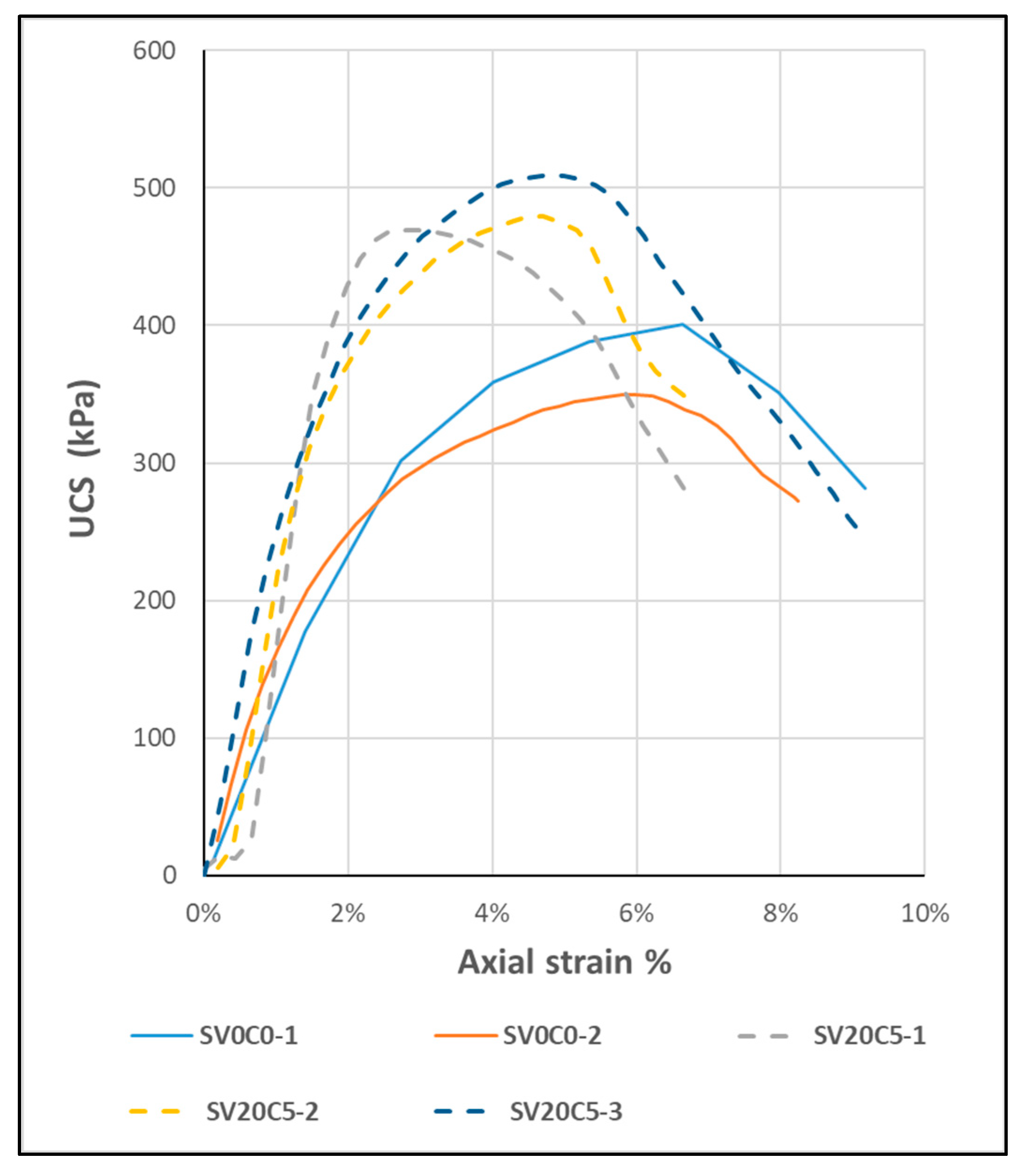

Figure 23.

UCS curve of specimens SV0C0 and SV20C5.

Figure 23.

UCS curve of specimens SV0C0 and SV20C5.

Table 1.

Range of fines content and Atterberg limits; values reported in the literature.

Table 1.

Range of fines content and Atterberg limits; values reported in the literature.

| Index Property | Reference |

|---|

| Montero and Estaire (2015) [24] | Vázquez-Boza (2014) [30] |

|---|

| Fines (<0.075 mm, %) | 90.7–99.5 | 96.3–100.0 |

| Liquid Limit, LL (%) | 45.4–58.5 | 22.3–27.16 |

| Plasticity Index, PI | 20.1–29.8 | 29.4–36.8 |

| Specific Gravity, Gs | 2.65 | --- |

Table 2.

Distribution of chemical elements in volcanic ash, based on data reported by Melentijević [

33] and Martínez del Pozo [

17].

Table 2.

Distribution of chemical elements in volcanic ash, based on data reported by Melentijević [

33] and Martínez del Pozo [

17].

| Formula | Melentijević [33] | Martínez del Pozo [17] |

|---|

| Conc. (%) |

|---|

| SiO2 | 40.62 | 41.20 |

| CaO | 13.43 | 12.00 |

| Al2O3 | 13.71 | 14.90 |

| Fe2O3 | 15.55 | 15.10 |

| MgO | 5.80 | 4.40 |

| K2O | 1.89 | 2.40 |

| Na2O | 3.20 | 3.50 |

| TiO2 | 4.09 | 4.30 |

Table 3.

Soil mixture designation and ratios of materials used for sample preparation.

Table 3.

Soil mixture designation and ratios of materials used for sample preparation.

| Designation 1 | Conformation of Mixture | Soil–Ash Ratio | Lime–Ash Ratio | Soil–Lime Ratio |

|---|

| SVαCβ | WS + WV + WC | WV = α/100 ∗ WS | WC = β/100 ∗ WV | NA |

| SV0Cδ | WS + WC | NA | NA | WC = δ/100 ∗ Ws |

Table 4.

Designation and dosage of soil mixtures with V-C3 and C-1 on a dry weight basis and percentage by total dry weight.

Table 4.

Designation and dosage of soil mixtures with V-C3 and C-1 on a dry weight basis and percentage by total dry weight.

| Designation | Dry Weight (g) | % by Total Dry Weight |

|---|

Soil

(S1-S2) | Volcanic Ash

(V-C3) | Lime

(C-1) | Total Sample | Soil

(S1-S2) | Volcanic Ash

(V-C3) | Lime

(C-1) |

|---|

| SV0C0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| SV10C0 | 100.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 110.0 | 90.9 | 9.1 | 0.0 |

| SV20C0 | 100.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 120.0 | 83.3 | 16.7 | 0.0 |

| SV30C0 | 100.0 | 30.0 | 0.0 | 130.0 | 76.9 | 23.1 | 0.0 |

| SV0C1 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 101.0 | 99.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| SV0C3 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 103.0 | 97.1 | 0.0 | 2.9 |

| SV0C5 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 105.0 | 95.2 | 0.0 | 4.8 |

| SV20C5 | 100.0 | 20.0 | 1.0 | 121.0 | 82.6 | 16.5 | 0.8 |

| SV30C5 | 100.0 | 30.0 | 1.5 | 131.5 | 76.0 | 22.8 | 1.1 |

| SV40C5 | 100.0 | 40.0 | 2.0 | 142.0 | 70.4 | 28.2 | 1.4 |

Table 5.

Standards and test procedures performed.

Table 5.

Standards and test procedures performed.

| Property | Test | Specimens Tested | Procedure | Equipment and Working Conditions |

|---|

| Index properties | Sieve and laser particle size measurement | 3 | ASTM D422-63 (2007)e2 [36] | The size distribution of the soil through particle size sieve analysis. A particle size smaller than 704 µm was determined by laser granulometry using Honeywell Microtrac X100 equipment. |

| Atterberg limits | 7 | ASTM D4318-17e1 [37] | Procedure according to adopted international standard. |

| Chemical and mineralogical composition | X-Ray Diffraction XRD | 8 | IT-04345J0 6102 | Performed using BRUKER D8 Advance diffractometric equipment with CuKα radiation. The 1 g sample used was crushed in an agate mortar to sizes smaller than 53 µm. |

| X-Ray Fluorescence XRF | 6 | IT-04345J0 91 01 | Chemical analysis was performed using a BRUKER S2 Ranger spectrometer, by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) in SPECTRO Arcos equipment, with 9.2 g sample tablets and 0.8 g of wax. |

| Thermal analysis TGA | 3 | IT-04345J0 51 01 | The preservation state of the lime was monitored by simultaneous thermal analysis (TG/DTA) in a TA Instrument SDT-Q600 under room temperature and 1000 °C, a heating rate of 10 °C/min, air atmosphere, and a flow rate of 100 mL/min. |

| Optical microscopy analysis | 6 | -- | Conducted using an optical microscope with reflected light and transmitted light at 40x magnification. |

| Compaction | Compaction (modified Proctor) | 2 | ASTM D1557-12 (2021) [35] | Using the modified Proctor compaction method and Modified Effort, (PM), the dry density–moisture curve was obtained. |

| Swelling and deformability | Free swellingOne-dimensional consolidation | 10 | ASTM D4546-21 [38] | To characterize swelling and deformability of the soils and mixtures, the test specimens were tested in oedometers for samples prepared by compaction at energy equivalent to the Modified Effort [35]. |

| Resistance | Unconfined compressive strength | 5 | ASTM D2435/D2435M-11 [39] | The test was performed on specimens of 37.9 mm in diameter and 76.7 mm in height compacted by an energy equivalent to MP at 1 mm/min velocity. |

| Direct shear | 9 | ASTM D2166/D2166M-16 [40] | The resistance properties under drained conditions on a circular specimen of 50 mm diameter and 25 mm height, compacted by energy equivalent to PM, which was saturated and consolidated prior to failure at 0.003 mm/min velocity. |

Table 6.

Distribution of chemical elements in base soil S1 (SV0C0), V-C3, C-1, and soil mixtures based on soil S1.

Table 6.

Distribution of chemical elements in base soil S1 (SV0C0), V-C3, C-1, and soil mixtures based on soil S1.

| Formula | V-C3 | C-1 | SV0C0 | SV10C0 | SV20C0 | SV10C5 | SV20C5 |

|---|

| Conc. (%) |

|---|

| SiO2 | 40.62 | 13.98 | 36.06 | 36.64 | 36.85 | 36.49 | 36.72 |

| CaO | 13.43 | 55.01 | 21.33 | 21.00 | 21.12 | 21.11 | 21.16 |

| Al2O3 | 13.71 | 4.40 | 11.63 | 11.93 | 12.02 | 11.90 | 11.89 |

| Fe2O3 | 15.55 | 1.94 | 3.98 | 4.81 | 5.42 | 4.97 | 5.52 |

| MgO | 5.80 | 5.10 | 2.60 | 2.80 | 2.90 | 2.80 | 3.00 |

| K2O | 1.89 | 1.54 | 2.24 | 2.23 | 2.24 | 2.23 | 2.22 |

| Na2O | 3.20 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 1.00 |

| TiO2 | 4.09 | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.73 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.91 |

| Cl | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| SO3 | 0.33 | 1.59 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| P2O5 | 0.64 | - | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| SrO | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| MnO | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| ZrO2 | 0.05 | - | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.09 | - | - | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| ZnO | 0.01 | - | - | - | 0.01 | 0.01 | - |

| V2O5 | 0.07 | - | - | - | - | 0.02 | - |

| CuO | 0.01 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| LOI | −0.51 | 15.30 | 20.50 | 18.59 | 17.20 | 18.42 | 17.10 |

Table 7.

Quantification of crystalline phase distribution of base soil S1, C-1, V-C3, and soil mixtures based on soil S1.

Table 7.

Quantification of crystalline phase distribution of base soil S1, C-1, V-C3, and soil mixtures based on soil S1.

| Crystalline Phase | Formula | V-C3 | C-1 | SV0C0 | SV10C0 | SV20C0 | SV10C5 | SV20C5 |

|---|

| % |

|---|

| Quartz | SiO2 | -- | 6.2 | 20.7 | 17.3 | 19.2 | 16.4 | 21.1 |

| Potassium Feldspar | KAlSi3O8 | -- | -- | 3.0 | 6.3 | 5.0 | 2.6 | 3.9 |

| Plagioclase | (NaCa)Al2Si2O8 | 34.0 | -- | 6.5 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 11.3 | 7.7 |

| Phyllosilicates (Ms) | K0.94Al1.96(Al0.95Si2.85O10)((OH)1.744F0.256) | -- | 11.3 | 38.5 | 35.7 | 36.9 | 38.1 | 37.4 |

| Calcite | Ca(CO3) | -- | 27.8 | 25.5 | 24.4 | 25.2 | 27.4 | 25.5 |

| Dolomite | CaMg(CO3)2 | -- | -- | 5.8 | 7.4 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.3 |

| Olivine | (Mg,Fe)2SiO4 | 19.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Pyroxene (Diopside) | MgCaSi2O6 | 36.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Amphibole (Kaerstutite) | {Na}{Ca2}{Mg3AlTi}(Al2Si6O22)O2 | 4.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Ti-Magnetite | Fe2TiO4 | 5.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Ilmenite | FeTiO3 | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Hematite | Fe2O3 | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Portlandite | Ca(OH)2 | -- | 10.5 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Larnite | Ca2(SiO4) | -- | 44.2 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

Table 8.

Quantification of the crystalline phase distribution of lime (C-1, C-2, and C-3).

Table 8.

Quantification of the crystalline phase distribution of lime (C-1, C-2, and C-3).

| Crystalline Phase | Formula | C-1 | C-2 | C-3 | Commercial Supplier |

|---|

| % |

|---|

| Quartz | SiO2 | 6.2 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 2.0–5.0 |

| Calcite | Ca(CO3) | 27.8 | 30.3 | 31.6 | 20.0–25.0 |

| Portlandite | Ca(OH)2 | 10.5 | 8.4 | 9.8 | 20.0–25.0 |

| Phyllosilicates | K0.94Al1.96(Al0.95Si2.85O10)((OH)1.744F0.256) | 11.3 | 14.1 | 10.8 | --- |

| Larnite | Ca2(SiO4) | 44.2 | 40.6 | 41.0 | 35.0–40.0 |

Table 9.

Average temperature and weight loss values of reactions determined by TGA for C-1, C-2, and C-3.

Table 9.

Average temperature and weight loss values of reactions determined by TGA for C-1, C-2, and C-3.

| Reaction | Ti–Tf (°C) | TMáx (°C) | E (J/g) | Weight Loss (%) |

|---|

| 1 | 350–440 | 390 | 194 | 3.2 |

| 2 | 580–730 | 700 | 365 | 10.5 |

Table 10.

Comparison of granulometric results of S1 and S2.

Table 10.

Comparison of granulometric results of S1 and S2.

| Parameter (Unit) | SV0C0 (S1–S2) | Montero and Estaire (2015) [24] | Vázquez-Boza (2014) [30] |

|---|

| Fraction < N°200 (%) | 90.2–99.9 | 90.7–99.5 | 96.3–100.0 |

Table 11.

Atterberg limits for soil and mixtures.

Table 11.

Atterberg limits for soil and mixtures.

| Sample | LL (%) | PL (%) | PI |

|---|

| SV0C0-1 (S1) | 56.3 | 23.0 | 33.4 |

| SV0C0-2 (S2) | 44.1 | 19.7 | 24.4 |

| SV0C0-3 (S2) | 50.2 | 20.6 | 29.6 |

| SV10C0 (S1) | 56.0 | 22.6 | 33.4 |

| SV20C0 (S1) | 55.8 | 20.7 | 35.2 |

| SV10C5 (S1) | 57.8 | 23.2 | 34.6 |

| SV20C5 (S1) | 53.6 | 22.2 | 31.4 |

Table 12.

Comparison of Atterberg limits results for SV0C0 (S1-S2) and reference soil samples.

Table 12.

Comparison of Atterberg limits results for SV0C0 (S1-S2) and reference soil samples.

| Parameter (Unit) | SV0C0 (S1–S2) | Montero and Estaire (2015) [24] | Vázquez-Boza (2014) [30] |

|---|

| Liquid Limit LL (%) | 44.1–56.3 | 45.4–58.5 | 51.7–64.7 |

| Plasticity Index PI (%) | 24.4–33.4 | 20.1–29.8 | 29.4–36.8 |

Table 13.

Compaction parameters by the modified Proctor test.

Table 13.

Compaction parameters by the modified Proctor test.

| Parameter (Unit) | SV0C0 | SV20C5 |

|---|

| Specific maximum dry weight (kN/m3) | 15.9 | 17.2 |

| Optimum moisture content (%) | 22.3 | 16.5 |

Table 14.

Summary of fines content, clay fraction, Atterberg limits, and clay activity for soils S1 and S2.

Table 14.

Summary of fines content, clay fraction, Atterberg limits, and clay activity for soils S1 and S2.

| Index Property | Soil Sample |

|---|

| S1 | S2 |

|---|

| Fines (<0.075 mm, %) | 90.2 | 94.9–99.9 |

| Clay fraction (<0.002 mm, %) | 16.0 | 22.3–27.16 |

| Liquid Limit, LL (%) | 56.3 | 44.1–50.2 |

| Plastic Limit, PL (%) | 23.0 | 19.7–20.6 |

| Plasticity Index, PI | 33.4 | 24.4–29.6 |

| Clay activity, A | 2.08 | 1.33 |

Table 15.

Classification of swelling potential by direct measurement in the oedometer test.

Table 15.

Classification of swelling potential by direct measurement in the oedometer test.

| Identification | Free Swelling (%) | Expansion Index, EI | Potential Expansion (ASTM D4829 [49]) 1 |

|---|

| SV0C0 (wi 16.5%) (S1) | 11.89 | 118 | H |

| SV0C1 (S2) | 8.05 | 80 | M |

| SV0C3 (S2) | 5.70 | 57 | M |

| SV0C5 (S1) | 3.42 | 34 | L |

| SV10C0 (S1) | 9.01 | 90 | H |

| SV20C0 (S1) | 7.55 | 75 | M |

| SV30C0 (S2) | 6.19 | 61 | M |

| SV20C5 (S1) | 5.66 | 56 | M |

| SV30C5 (S2) | 3.47 | 34 | L |

| SV40C5 (S2) | 1.67 | 16 | VL |

Table 16.

Direct shear test parameters under peak strength conditions.

Table 16.

Direct shear test parameters under peak strength conditions.

| Mixture | Peak Strength Parameters |

|---|

| Cohesion (kPa) | Friction Angle (°) |

|---|

| SV30C5 | 41.3 | 20.1 |

| SV20C5 | 34.6 | 19.5 |

| SV0C0 | 37.8 | 19.2 |

| V-C3 | 4.4 | 33.8 |

Table 17.

Specimen preparation properties and results for UCS.

Table 17.

Specimen preparation properties and results for UCS.

| Sample | Initial Moisture Content (%) | Specific Dry Unit Weight (kN/m3) | UCS (kPa) | Axial Def (%) | E50 (MPa) |

|---|

| SV0C0-1 | 22.3 | 16.0 | 401 | 7 | 6.1 |

| SV0C0-2 | 22.3 | 16.1 | 350 | 6 | 5.8 |

| SV20C5-1 | 16.5 | 17.2 | 469 | 3 | 16.7 |

| SV20C5-2 | 16.5 | 17.0 | 479 | 5 | 10.2 |

| SV20C5-3 | 16.5 | 17.1 | 510 | 5 | 10.6 |