Critical Stress Conditions for Foam Glass Aggregate Insulation in a Flexible Pavement Layered System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. FGA Properties

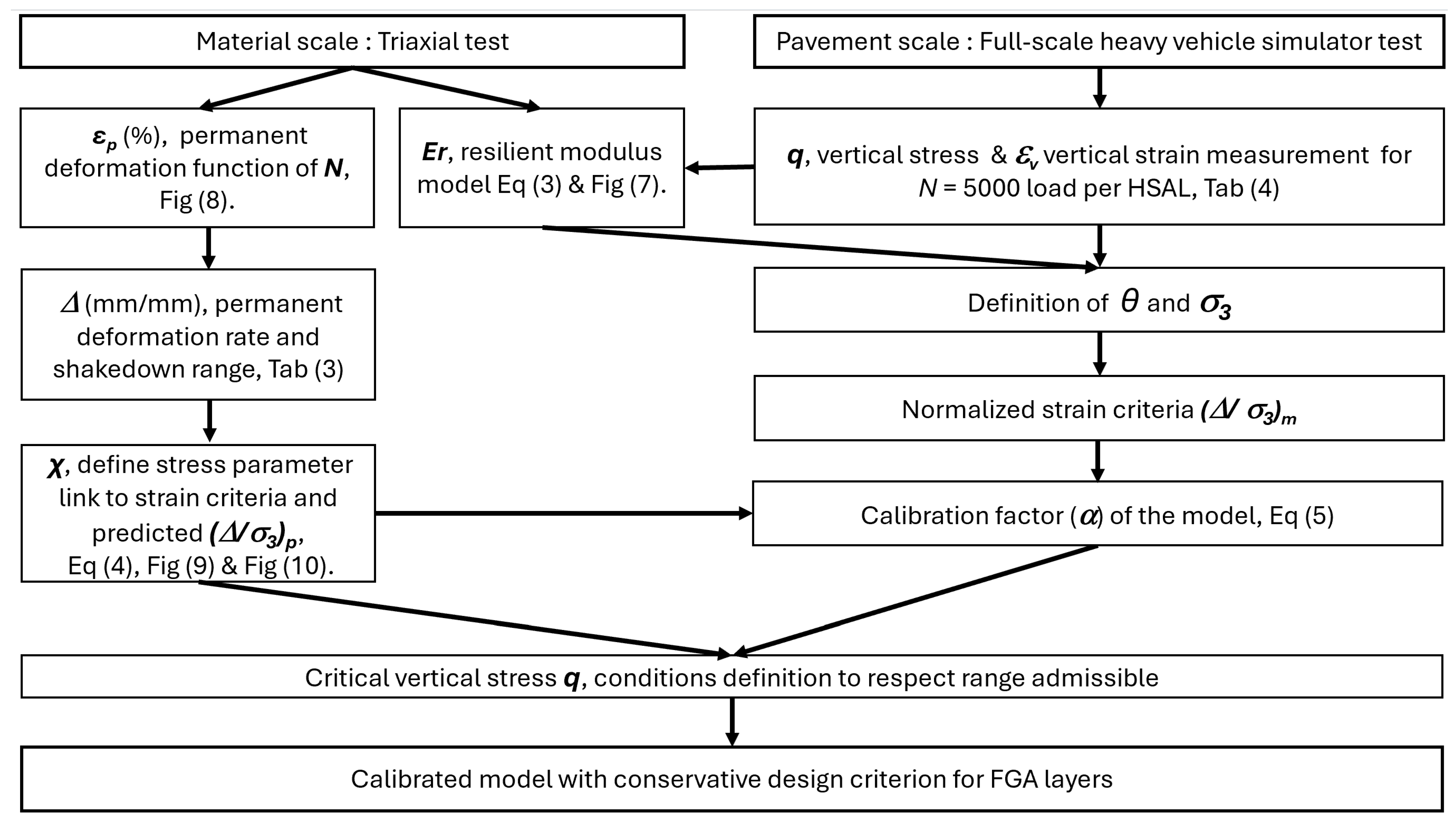

4. Methods

4.1. Triaxial Tests

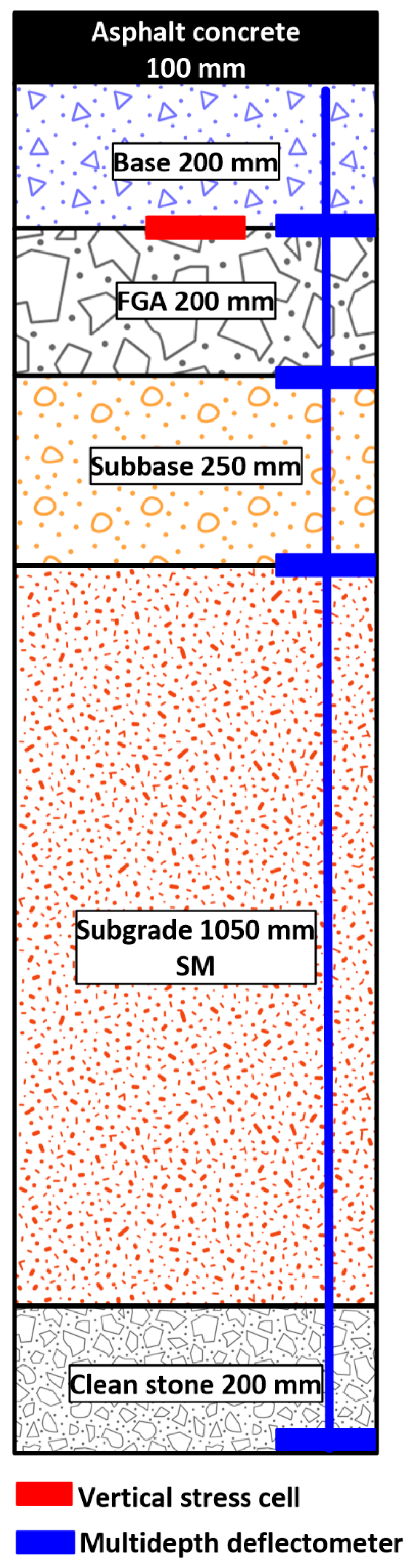

4.2. Heavy Vehicle Simulator Tests

5. Results

5.1. Triaxial Test Results

5.2. Heavy Vehicle Simulator Test Results

6. Conclusions

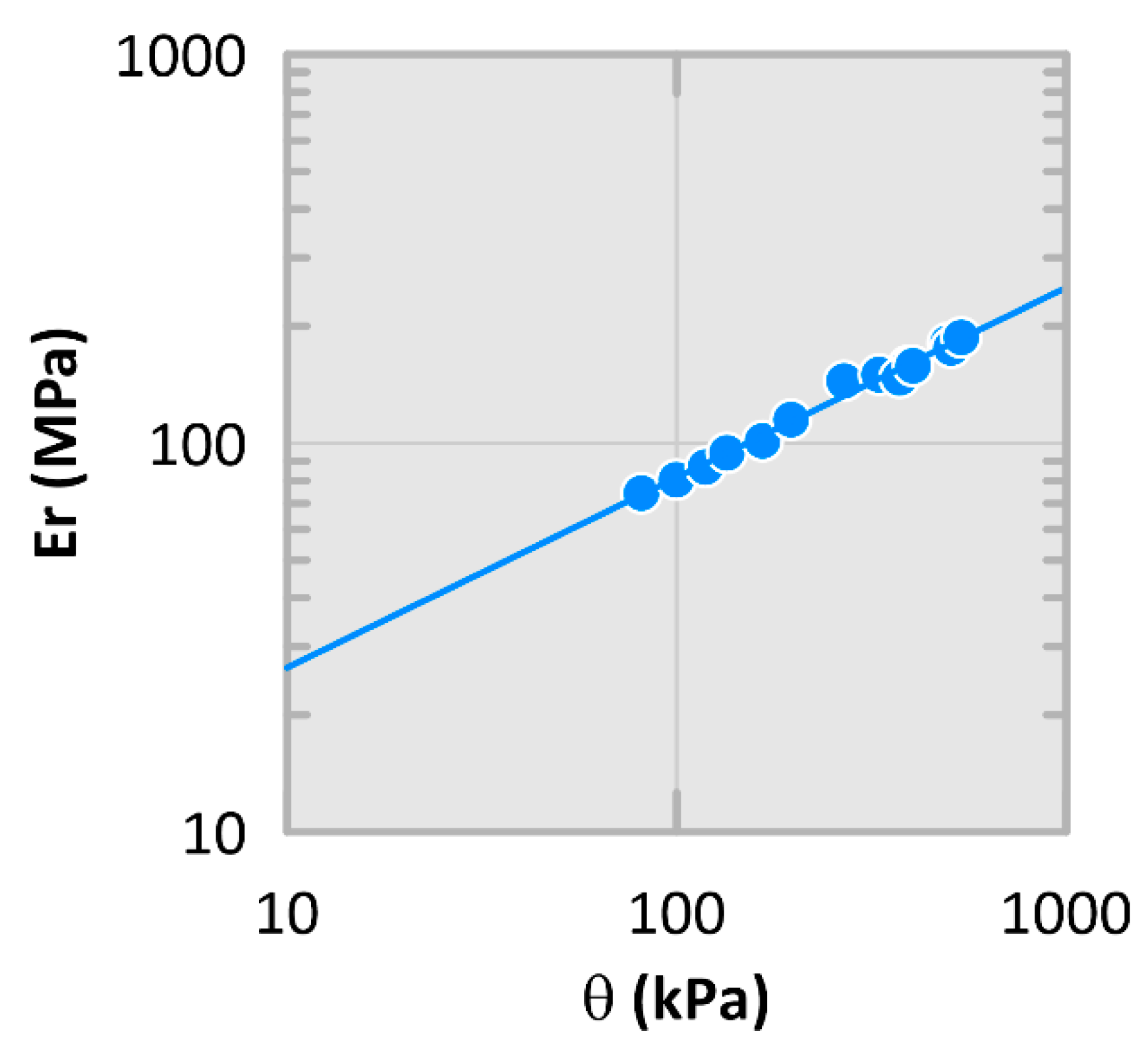

- For the foam glass aggregates tested, the Er varies between approximately 70 and 200 MPa for the range of stresses tested;

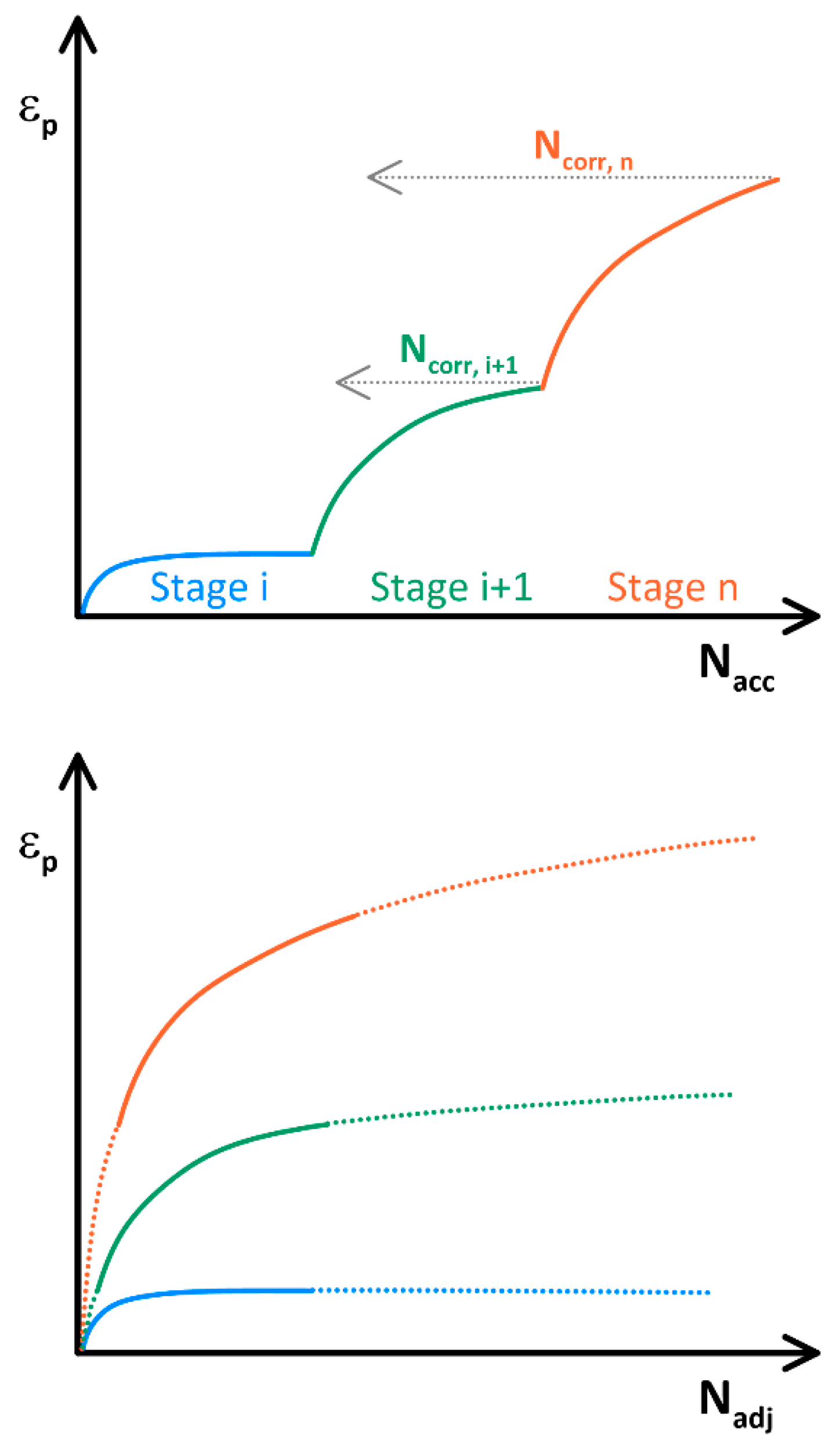

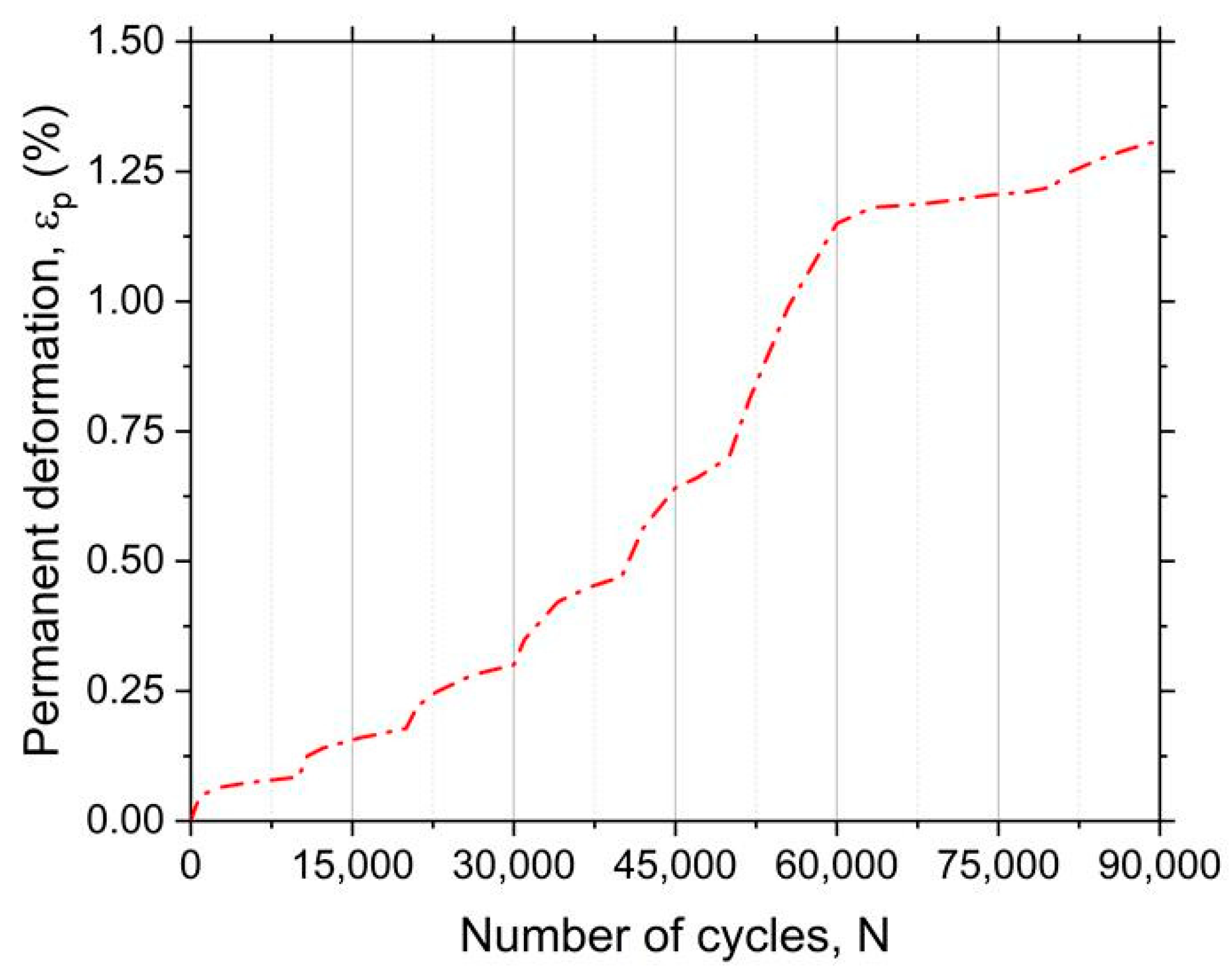

- Foam glass aggregates experience shakedown behavior when subjected to triaxial permanent deformation tests;

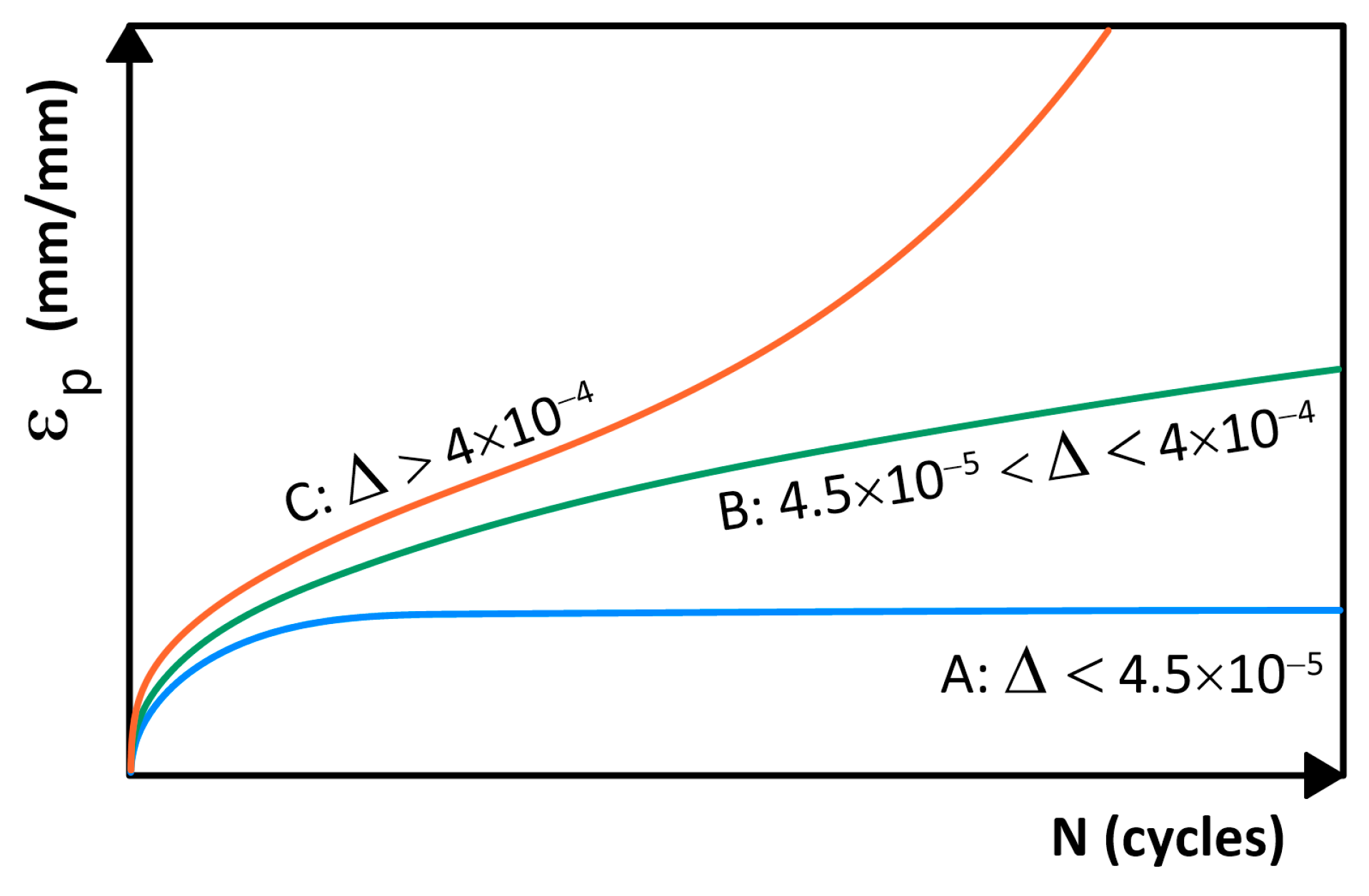

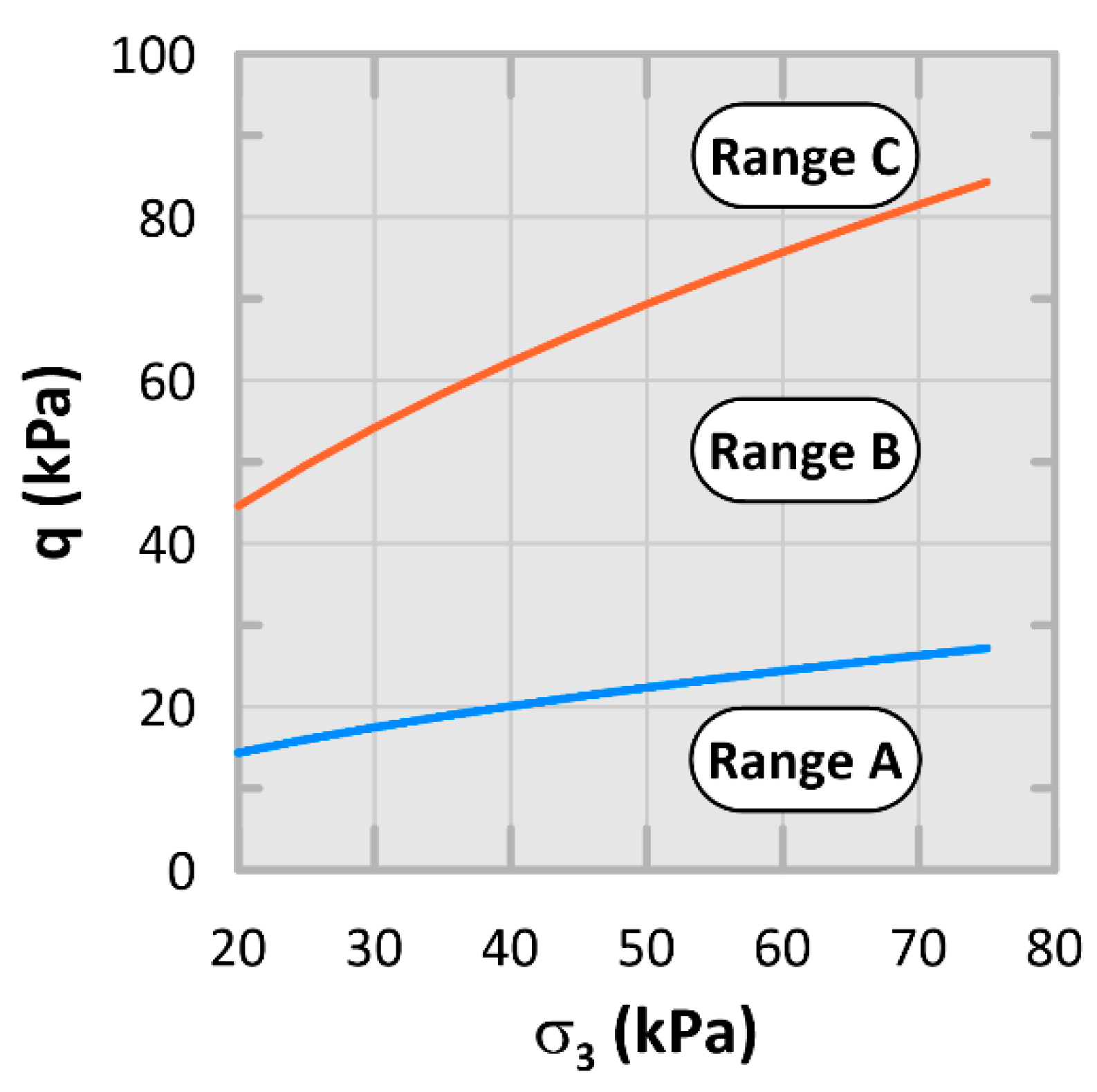

- Foam glass aggregates have mostly exhibited Range B and C behavior during permanent deformation triaxial characterization, demonstrating a significant sensitivity to the accumulation of permanent deformation;

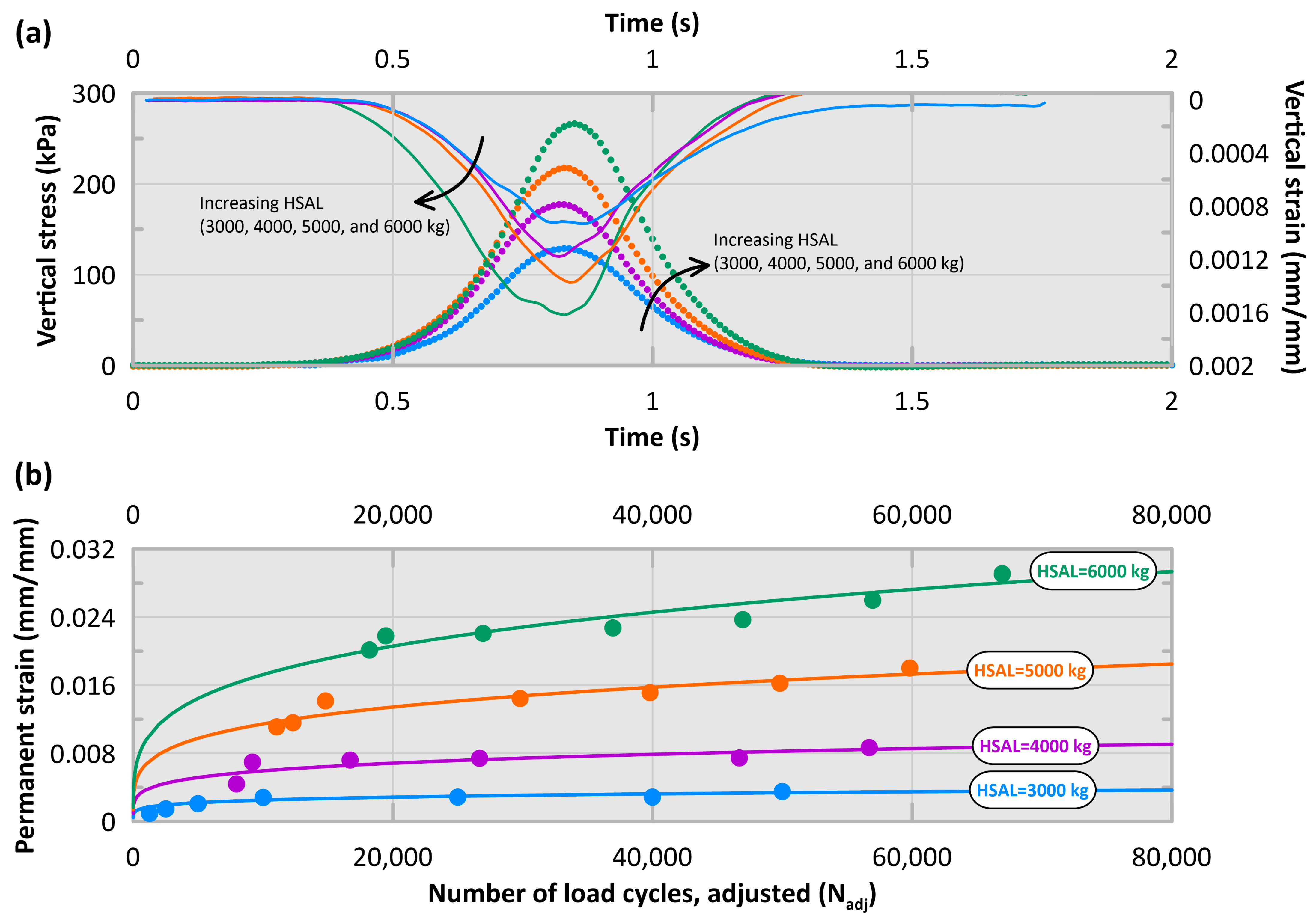

- Full-scale tests with a heavy vehicle simulator revealed that the strain hardening modeling approach was adapted to the permanent deformation behavior of the tested foam glass aggregates;

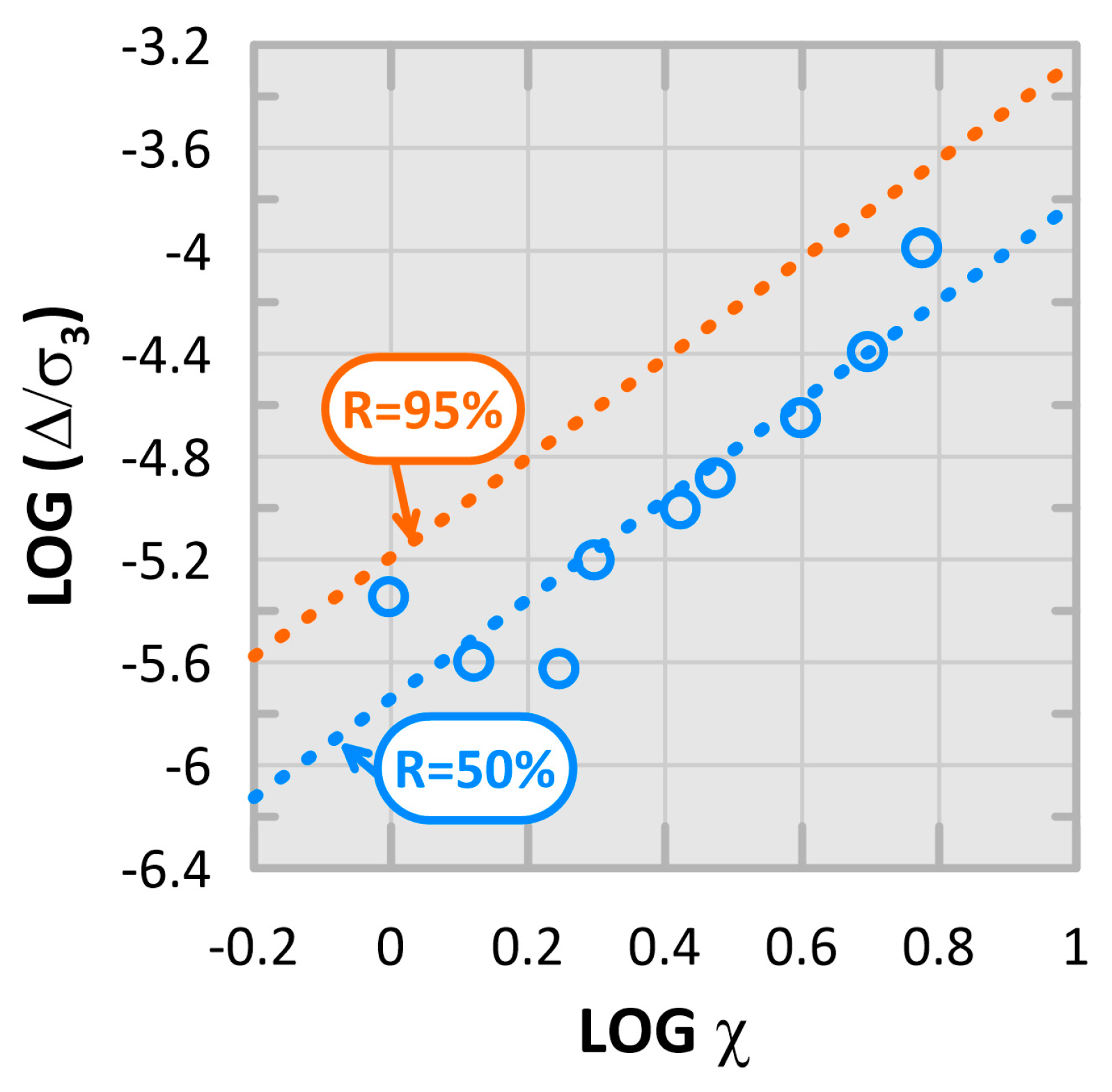

- The normalized strain criteria can be modeled with respect to a stress parameter for the triaxial and full-scale tests;

- Using the normalized strain criteria model, a calibration factor between laboratory scale and full-scale was calculated and equals 0.67;

- For a reliability level of 95%, the critical vertical stress for the tested foam glass aggregates to meet the Range A limit varies between 15 and 25 kPa for typical expected confining pressure values.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Doré, G.; Zubeck, H.K. Cold Regions Pavement Engineering; American Society of Civil Engineers Press: Reston, VA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Konrad, J.-M.; Roy, M. Flexible pavements in cold regions: A geotechnical perspective. Can. Geotech. J. 2000, 37, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvestre, O.; Bilodeau, J.-P.; Doré, G. Effect of frost heave on long-term roughness deterioration of flexible pavement structures. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2019, 20, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, J.-M. Frost susceptibility related to soil index properties. Can. Geotech. J. 1999, 36, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Laurent, D. Routine Mechanistic Pavement Design against Frost Heave. In Proceedings of the Cold Regions Engineering 2012: Sustainable Infrastructure Development in a Changing Cold Environment, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 19 August 2012; pp. 144–154. [Google Scholar]

- Transportation Association of Canada. Pavement Asset Design and Management Guide; TAC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arnevik, A.; Hoff, I.; Myren, T.H. Thermal and mechanical performance of foam glass aggregates in road structures. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2020, 170, 1029102. [Google Scholar]

- Rieksts, K.; Loranger, B.; Hoff, I. The performance of different frost protection materials for road design. In Eleventh International Conference on the Bearing Capacity of Roads, Railways and Airfields, Volume 2; Hoff, I., Mork, H., Saba, R.G., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segui, P.; Bilodeau, J.-P.; Doré, G. Mechanical behavior of pavement structures containing foam glass aggregates insulation layer: Laboratory and in-situ study. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cold Regions Engineering, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 19–22 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Segui, P.; Bilodeau, J.-P.; Côté, J.; Doré, G. Thermal behavior of flexible pavement containing foam glass aggregates as thermal insulation layer. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cold Regions Engineering, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 19–22 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.H. Pavement Analysis and Design, 2nd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- ARA Inc. Guide for the Mechanistic-Empirical Design of New and Rehabilitated Pavement Structures; Transportation Research Board of the National Academies: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Asphalt Institute. Thickness Design-Asphalt Pavements for Highways and Streets, 9th ed.; Asphalt Institute: Lexington, KY, USA, 1991; MS-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pidwerbesky, B.D. Fundamental Behaviour of Unbound Granular Pavements Subjected to Various Loading Conditions and Accelerated Trafficking. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- NSSGA. The Aggregates Handbook, 2nd ed.; National Stone, Sand and Gravel Association: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-9889950-0-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lekarp, F.; Isacsson, U.; Dawson, A. State of the Art. II: Permanent Strain Response of Unbound Aggregates. J. Transp. Eng. 2000, 126, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, E.L. Development of an Analysis Tool to Quantify the Effect of Superheavy Load Vehicles on Pavements. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Laval, Quebec City, QC, Cananda, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- AFNOR NF EN 13286-7; Mélanges Avec Ou Sans Liant Hydraulique Partie 7: Essai Triaxial Sous Charge Cyclique Pour Mélanges Sans Liant Hydraulique. Procédure de laboratoire de l’Association Française de Normalisation: Saint-Denis, France, 2005.

- Erlingsson, S.; Rahman, M.S. Evaluation of Permanent Deformation Characteristics of Unbound Granular Materials by Means of Multistage Repeated-Load Triaxial Tests. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2013, 2369, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werkmeister, S. Permanent Deformation Behaviour of Unbound Granular Materials in Pavement Constructions. Ph.D. Thesis, Dresden Technical University, Dresden, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo, E.; Cedro, R.; Florean, M.; Hreglich, S. Reutilization and stabilization of wastes by the production of glass foams. Ceram. Int. 2007, 33, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emersleben, A.; Meyer, N. The use of recycled glass for the construction of pavements. In Proceedings of the 2012 GeoCongress, Oakland, CA, USA, 25–29 March 2012; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Attila, Y.; Güden, M.; Taşdemirci, A. Foam glass processing using a polishing glass powder residue. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 5869–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Hägglund, J. Information 18:1. In Handbok: Skumglas i mark-och vägbyggnad; Swedich Geotechnical Institute: Linköping, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vegdirektoratet. Handboker i Statens vegvesen. In Håndbok N200 Vegbygging; Nr. Statens Vegvesens: Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Volland, S.; Vereshchagin, V. Cellular glass ceramic materials on the basis of zeolitic rock. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binhussain, M.A.; Marangoni, M.; Bernardo, E.; Colombo, P. Sintered and glazed glass-ceramics from natural and waste raw materials. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 3543–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni, M.; Secco, M.; Parisatto, M.; Artioli, G.; Bernardo, E.; Colombo, P.; Altlasi, H.; Binmajed, M.; Binhussain, M. Cellular glass–ceramics from a self foaming mixture of glass and basalt scoria. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2014, 403, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutov, A.; Yashurkaeva, L.; Alekseev, S.V.; Yashurkaev, T.V. Study of the structure of foam glass with different characteristics. Glass Ceram. 2007, 64, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritola, J.; Vares, S. Recycling of waste glass in foam glass production. In VTT Tiedotteita—Research Notes; VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland: Espoo, Finland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, Q.F.; Segui, P.; Côté, J.; Bilodeau, J.-P.; Doré, G. Thermal insulation of flexible pavements utilizing foam glass aggregates to mitigate frost action in cold regions—Development of design tools. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 414, 134841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, W.S.; Szendefy, J. Uniaxial dynamic behavior of foam glass aggregate under oedometric (fully side restrained) condition at different compaction ratios. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 396, 132327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenart, S.; Kaynia, A.M. Dynamic properties of lightweight foamed glass and their effect on railway vibration. Transp. Geotech. 2019, 21, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilodeau, J.-P.; Segui, P.; Pérez, E.L.; Doré, G. Empirical transfer functions for foam glass aggregates insulation used in flexible pavement layered systems. Transp. Geotech. 2024, 45, 101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AASHTO T307-99; Determining the Resilient Modulus of Soils and Aggregate Materials. In Standard Specifications for Transportation Materials and Methods of Sampling and Testing, 20th Edition. American Association for State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO): Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Pérez, E.L.; Bilodeau, J.-P.; Segui, P.; Doré, G. Resilient and permanent deformation of foam glass aggregates assemblies. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on the Bearing Capacity of Roads, Railways and Airfields, Trondheim, Norway, 27–30 June 2022; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Carrier, V. Comportement en Déformation Permanente et Mise en Œuvre des Matériaux Recyclés de Type MR5. Master’s Thesis, Université Laval, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Korkiiala-Tanttu, L.; Dawson, A. Relating full-scale pavement rutting to laboratory permanent deformation testing. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2007, 8, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, M.; Bilodeau, J.-P.; Pérez, E.L.; Fréchette, V.; Doré-Richard, S. Predicting plastic strain rate in the core of embankment dams subjected to heavy vehicle traffic. Can. Geotech. J. 2025, 62, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| σ3 (kPa) | q * (kPa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditioning | 103.4 | 103.4 | ||

| 1 | 20.7 | 20.7 | 41.4 | 62.1 |

| 2 | 34.5 | 34.5 | 68.9 | 103.4 |

| 3 | 68.9 | 68.9 | 137.9 | 206.8 |

| 4 | 103.4 | 68.9 | 103.45 | 206.8 |

| 5 | 137.9 | 103.4 | 137.9 | 275.8 |

| Test Sequence | N | q | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (kPa) | (kPa) | ||

| 1 | 10,000 | 20 | 20 |

| 10,000 | 20 | 40 | |

| 10,000 | 20 | 60 | |

| 10,000 | 20 | 80 | |

| 10,000 | 20 | 100 | |

| 10,000 | 20 | 120 | |

| 2 | 10,000 | 45 | 60 |

| 10,000 | 45 | 80 | |

| 10,000 | 45 | 120 |

| N | a | b | R2 | Range | q | q/σ3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mm/mm) | (kPa) | (kPa) | (mm/mm/kPa) | ||||||

| 10,000 | 0.000441 | 0.1336 | 0.9962 | B | 0.00009070 | 20 | 20 | 1 | 4.5348 × 10−6 |

| 10,000 | 0.0011 | 0.0987 | 0.9999 | B | 0.00012536 | 40 | 20 | 2 | 6.2681 × 10−6 |

| 10,000 | 0.0016 | 0.1196 | 1.000 | B | 0.00026262 | 60 | 20 | 3 | 1.3131 × 10−5 |

| 10,000 | 0.0020 | 0.1394 | 1.000 | C | 0.00045064 | 80 | 20 | 4 | 2.2532 × 10−5 |

| 10,000 | 0.0023 | 0.1699 | 0.9999 | C | 0.00081272 | 100 | 20 | 5 | 4.0636 × 10−5 |

| 10,000 | 0.0008 | 0.3293 | 0.9999 | C | 0.00204649 | 120 | 20 | 6 | 1.0232 × 10−4 |

| 10,000 | 0.0159 | 0.0127 | 0.9988 | A | 0.00011456 | 60 | 45 | 1.3 | 2.5458 × 10−6 |

| 10,000 | 0.0166 | 0.0115 | 0.9998 | B | 0.00010724 | 80 | 45 | 1.8 | 2.3830 × 10−6 |

| 10,000 | 0.0127 | 0.0469 | 0.9999 | B | 0.00044827 | 120 | 45 | 2.7 | 9.9615 × 10−6 |

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSAL = 3000 kg | HSAL = 4000 kg | HSAL = 5000 kg | HSAL = 6000 kg | |

| q (kPa) * | 151 | 181 | 224 | 264 |

| εV (mm/mm) * | 0.001 | 0.0011 | 0.0014 | 0.0016 |

| Er (MPa) * | 151 | 165 | 160 | 165 |

| θ (kPa) * | 353 | 420 | 397 | 423 |

| σ3 (kPa) * | 67 | 80 | 58 | 53 |

| q/σ3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 3.9 | 5.0 |

| a | 0.00045739 | 0.00091298 | 0.00137449 | 0.00164335 |

| b | 0.18455103 | 0.20333021 | 0.23024691 | 0.2552857 |

| Ncorr | 11,205 | 53,310 | 100,191 | 143,056 |

| Nacc | 0 to 5 × 104 | 5 × 104 to 1 × 105 | 1 × 105 to 1.5 × 105 | 1.5 × 105 to 2 × 105 |

| R2 | 0.922 | 0.624 | 0.889 | 0.916 |

| ΔFS (mm/mm) | 0.00019816 | 0.000508967 | 0.00108392 | 0.001767311 |

| (ΔFS/σ3)m (kPa−1) | 2.948 × 10−6 | 6.378 × 10−6 | 1.880 × 10−6 | 3.33 × 10−6 |

| (Δ/σ3)p (kPa−1) ** | 8.512 × 10−6 | 8.672 × 10−6 | 2.445 × 10−5 | 3.969 × 10−5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bilodeau, J.P.; Pérez-González, E.; Wang, D.; Segui, P. Critical Stress Conditions for Foam Glass Aggregate Insulation in a Flexible Pavement Layered System. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120339

Bilodeau JP, Pérez-González E, Wang D, Segui P. Critical Stress Conditions for Foam Glass Aggregate Insulation in a Flexible Pavement Layered System. Infrastructures. 2025; 10(12):339. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120339

Chicago/Turabian StyleBilodeau, Jean Pascal, Erdrick Pérez-González, Di Wang, and Pauline Segui. 2025. "Critical Stress Conditions for Foam Glass Aggregate Insulation in a Flexible Pavement Layered System" Infrastructures 10, no. 12: 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120339

APA StyleBilodeau, J. P., Pérez-González, E., Wang, D., & Segui, P. (2025). Critical Stress Conditions for Foam Glass Aggregate Insulation in a Flexible Pavement Layered System. Infrastructures, 10(12), 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120339