Performance Evaluation of Fiber-Reinforced Rubberized Paving-Blocks Containing Ceramic and Glass Wastes

Abstract

1. Introduction

Scope and Significance of the Study

2. Materials and Procedures

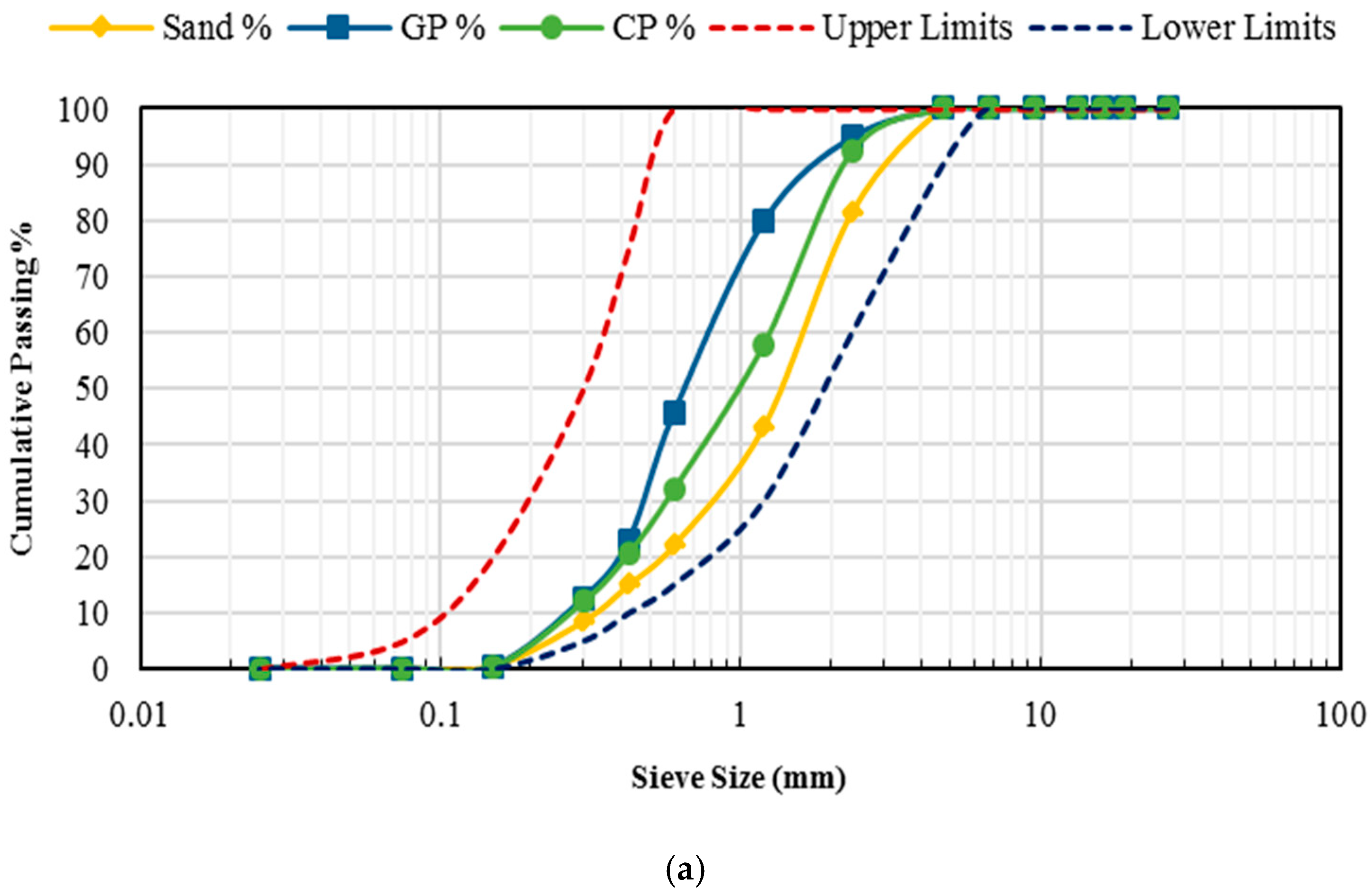

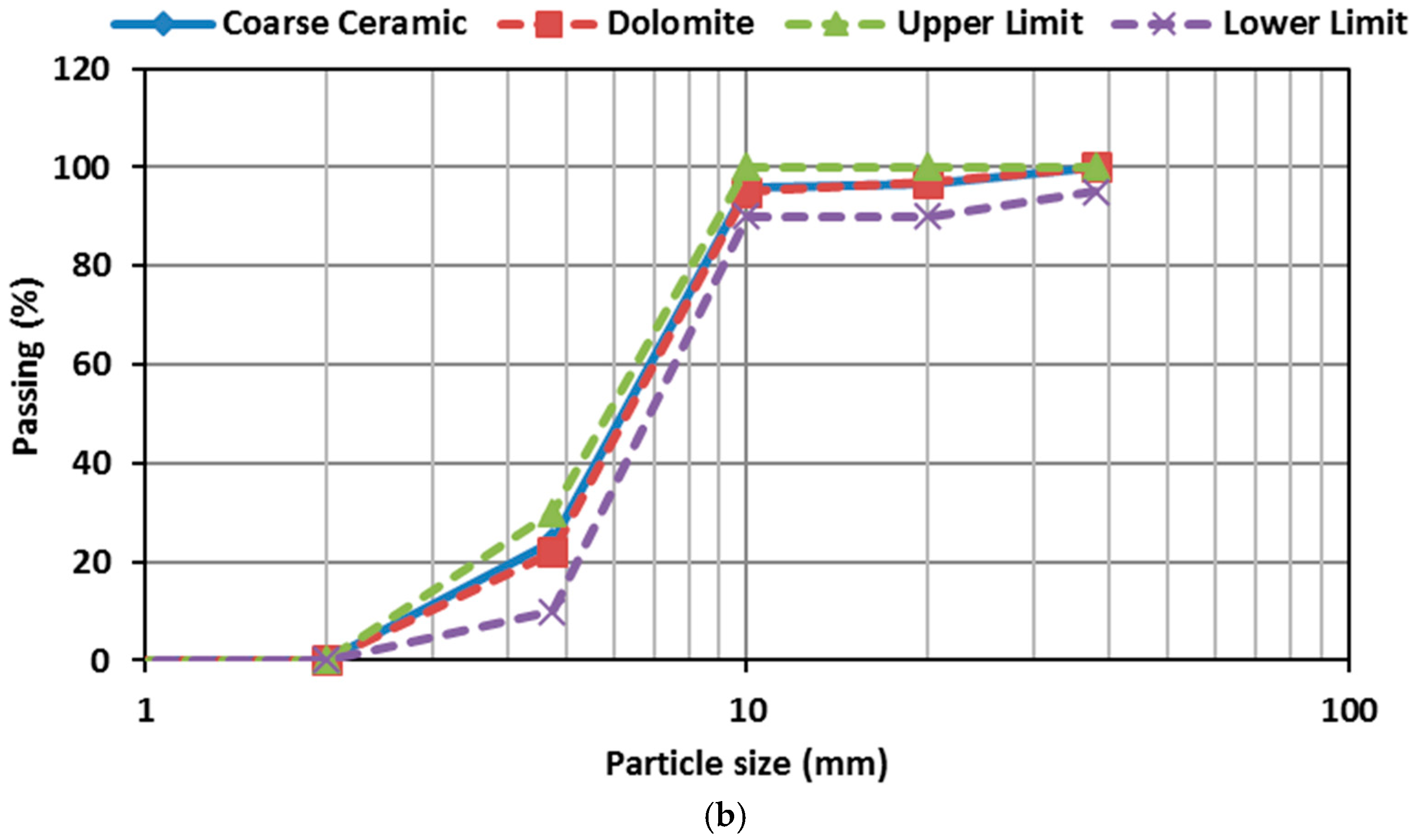

2.1. Materials

2.2. Mix Proportions

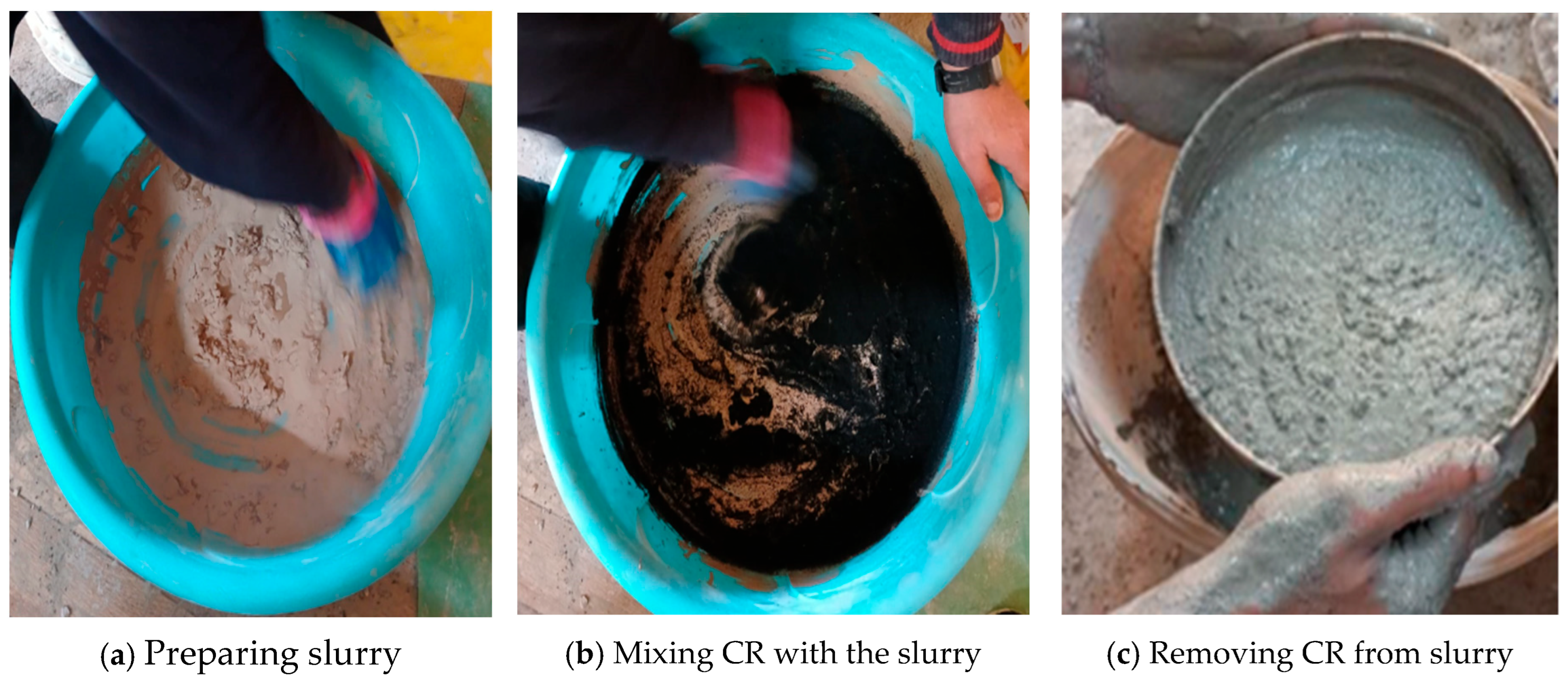

2.3. Physical Treatment of Crumb Rubber

2.4. Preparing and Casting of Specimens

2.5. Interlocking Paving Blocks Testing

2.5.1. Slump Test

2.5.2. Compressive Strength

2.5.3. Flexural Strength

2.5.4. Abrasion Resistance

2.5.5. Water Absorption

2.5.6. Microstructure Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

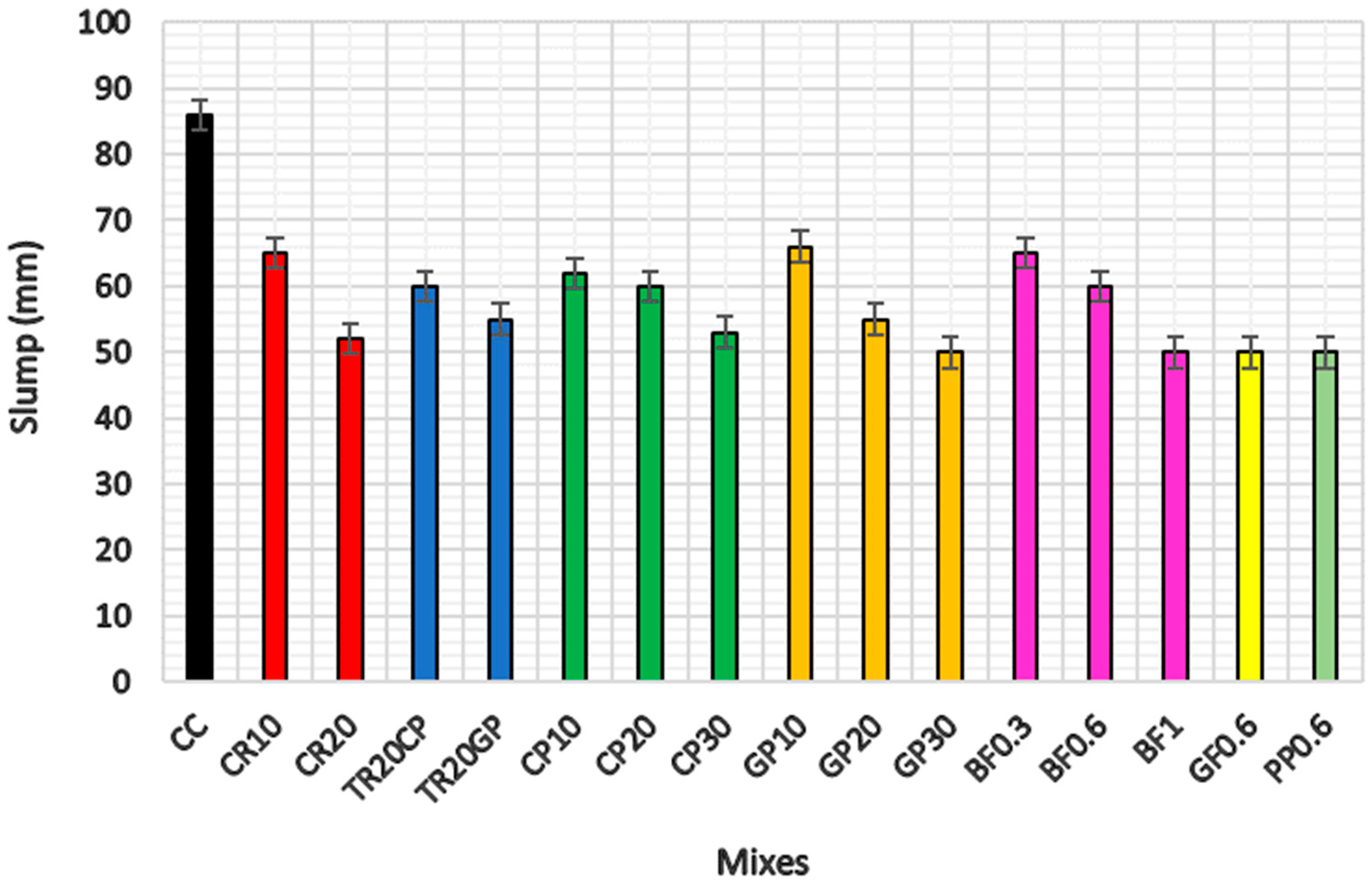

3.1. Consistency

3.2. Compressive Strength

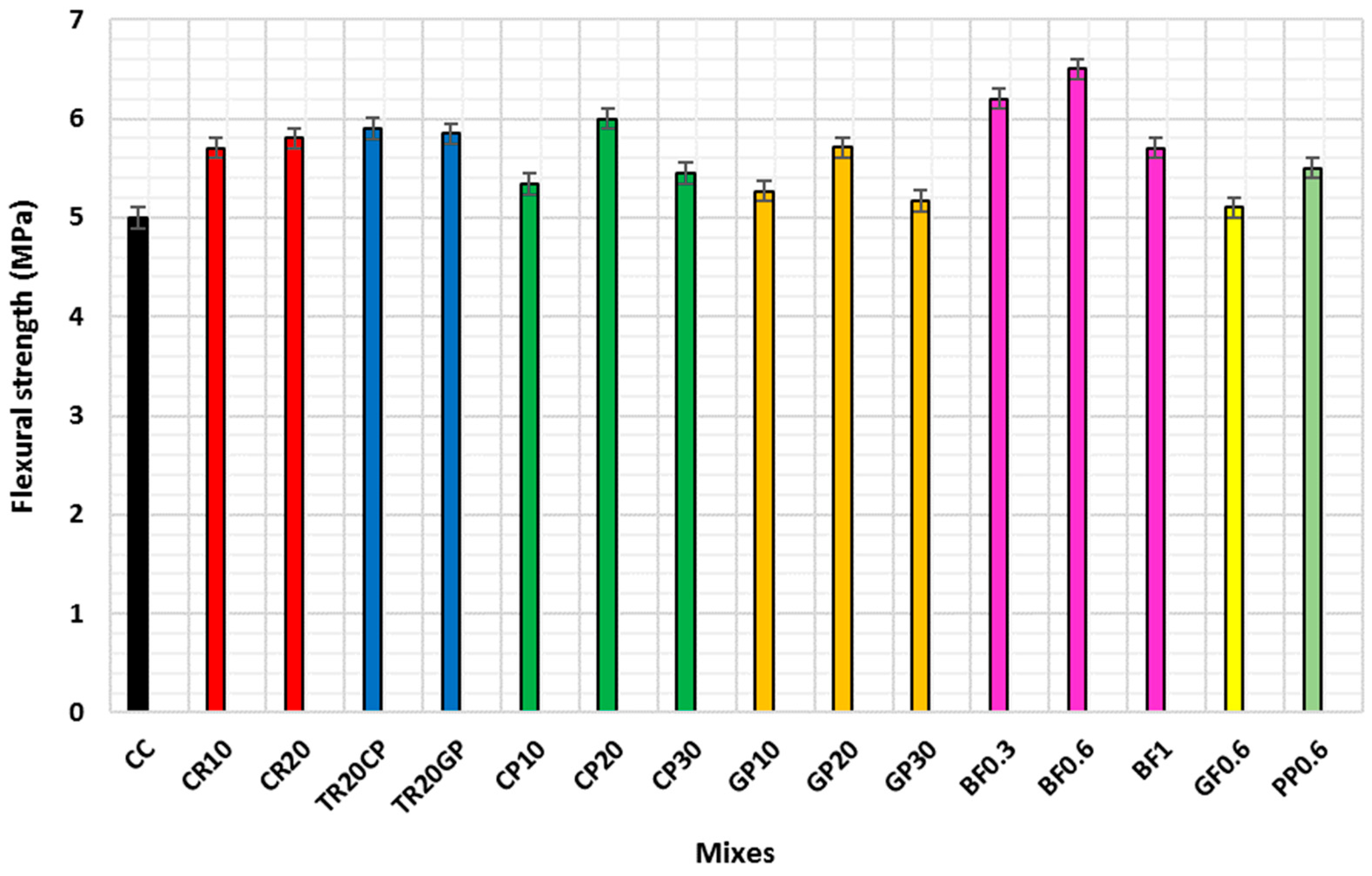

3.3. Flexural Strength

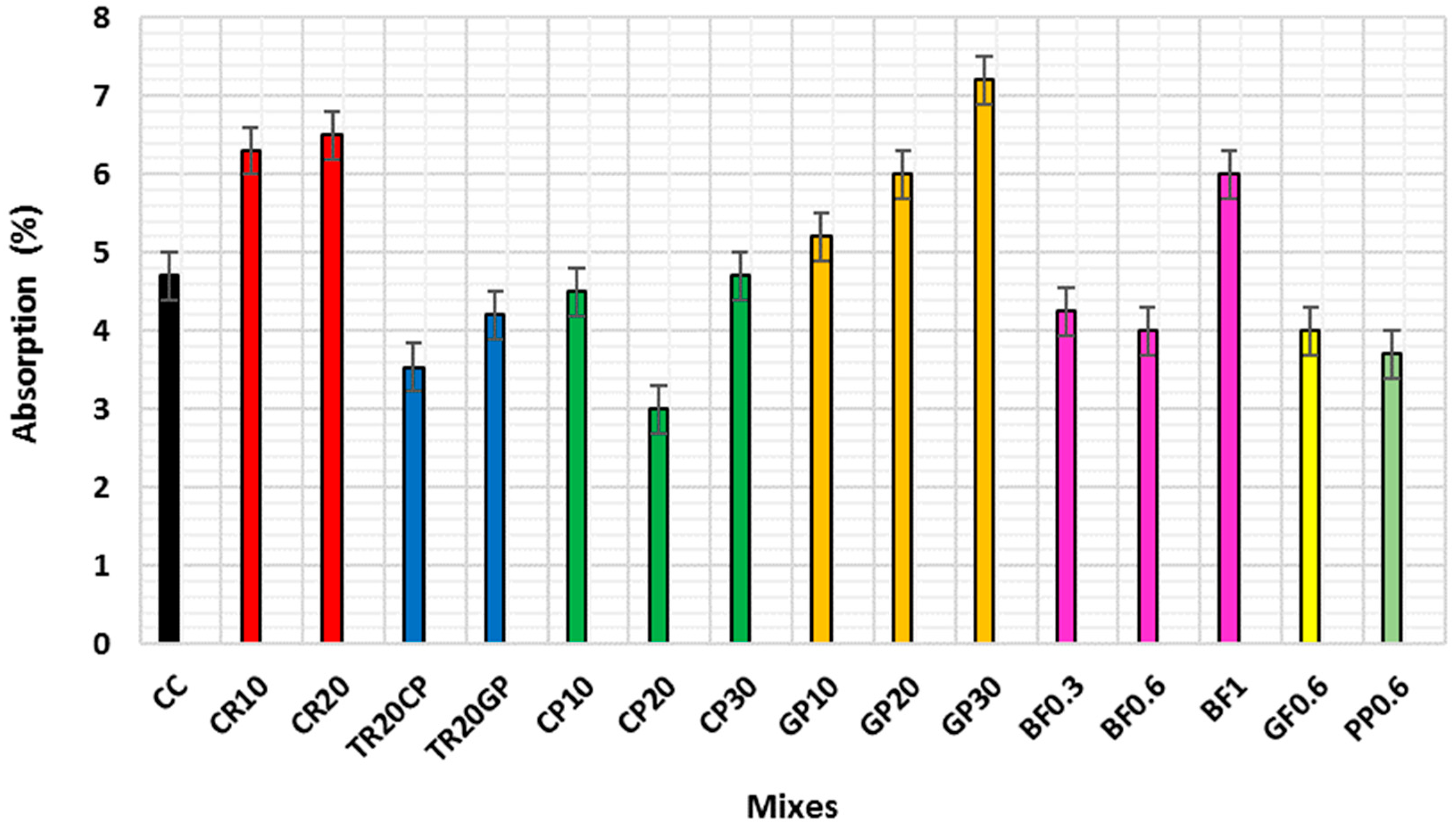

3.4. Water Absorption

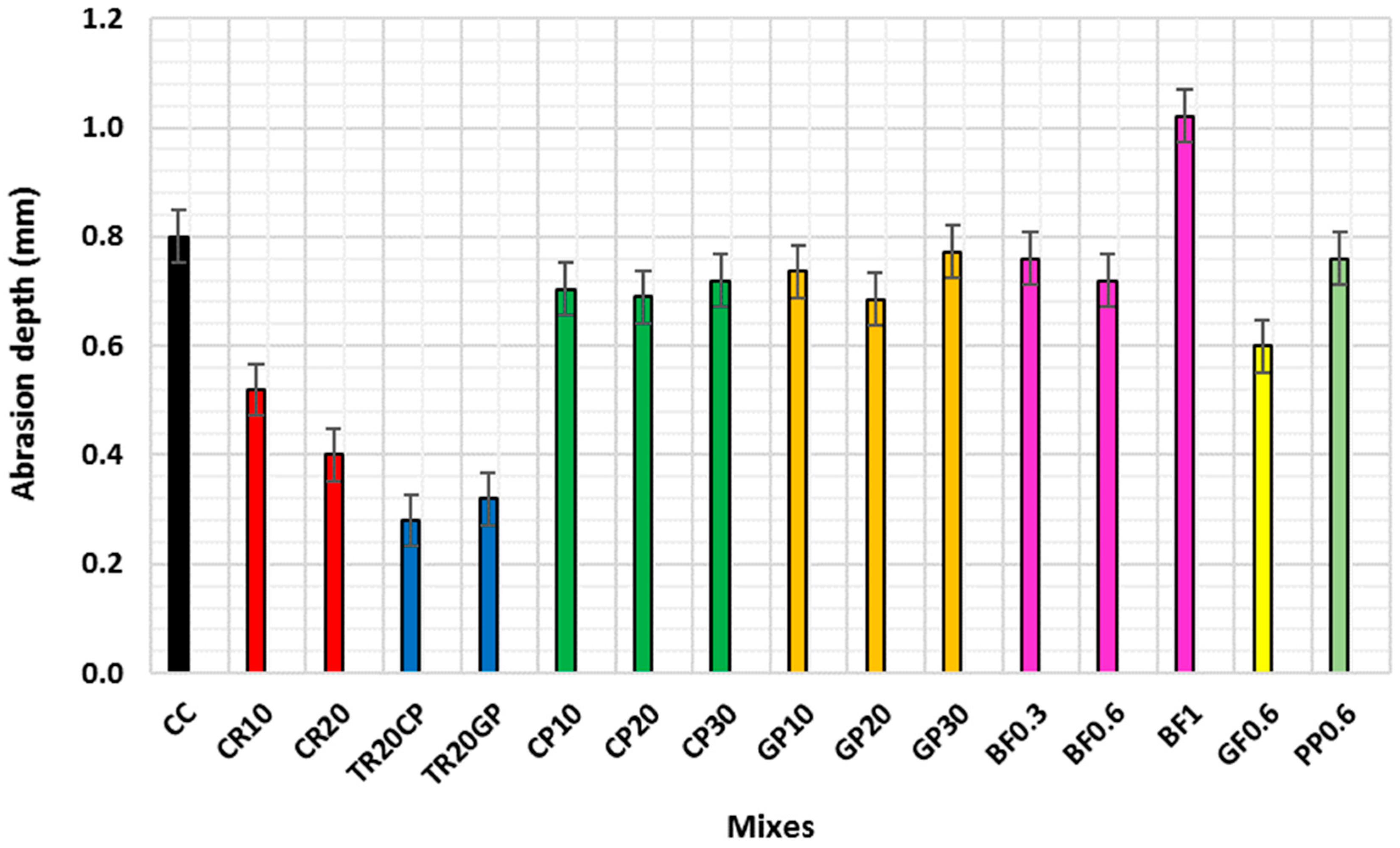

3.5. Abrasion Resistance

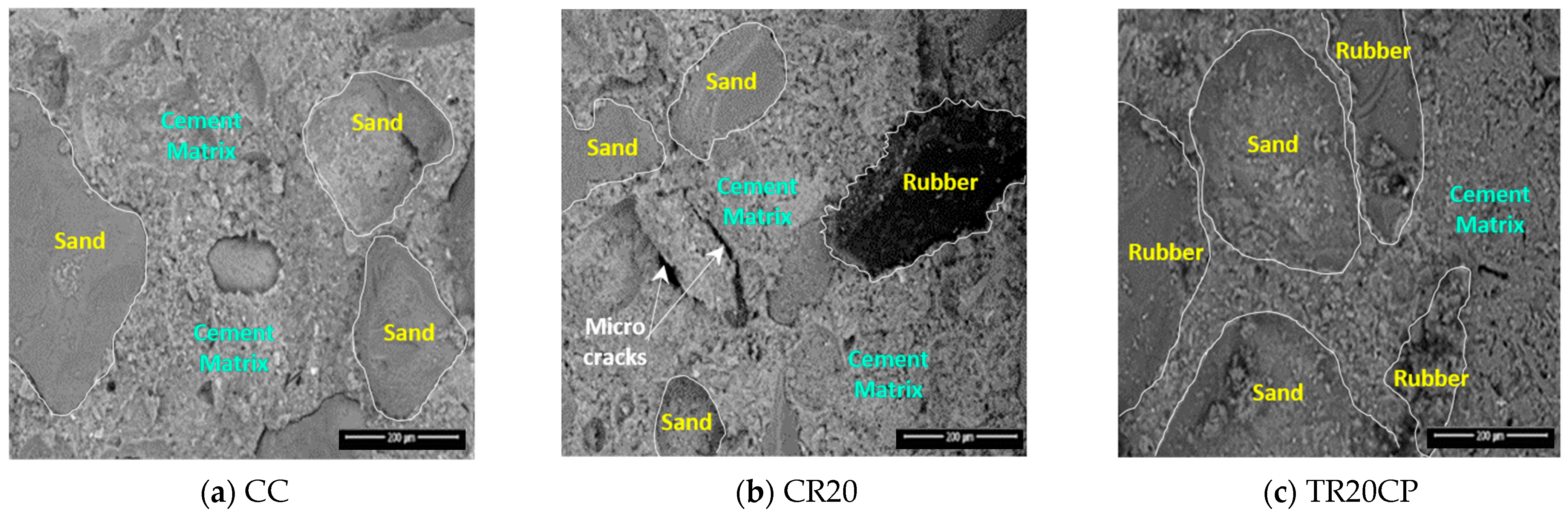

3.6. SEM Analysis

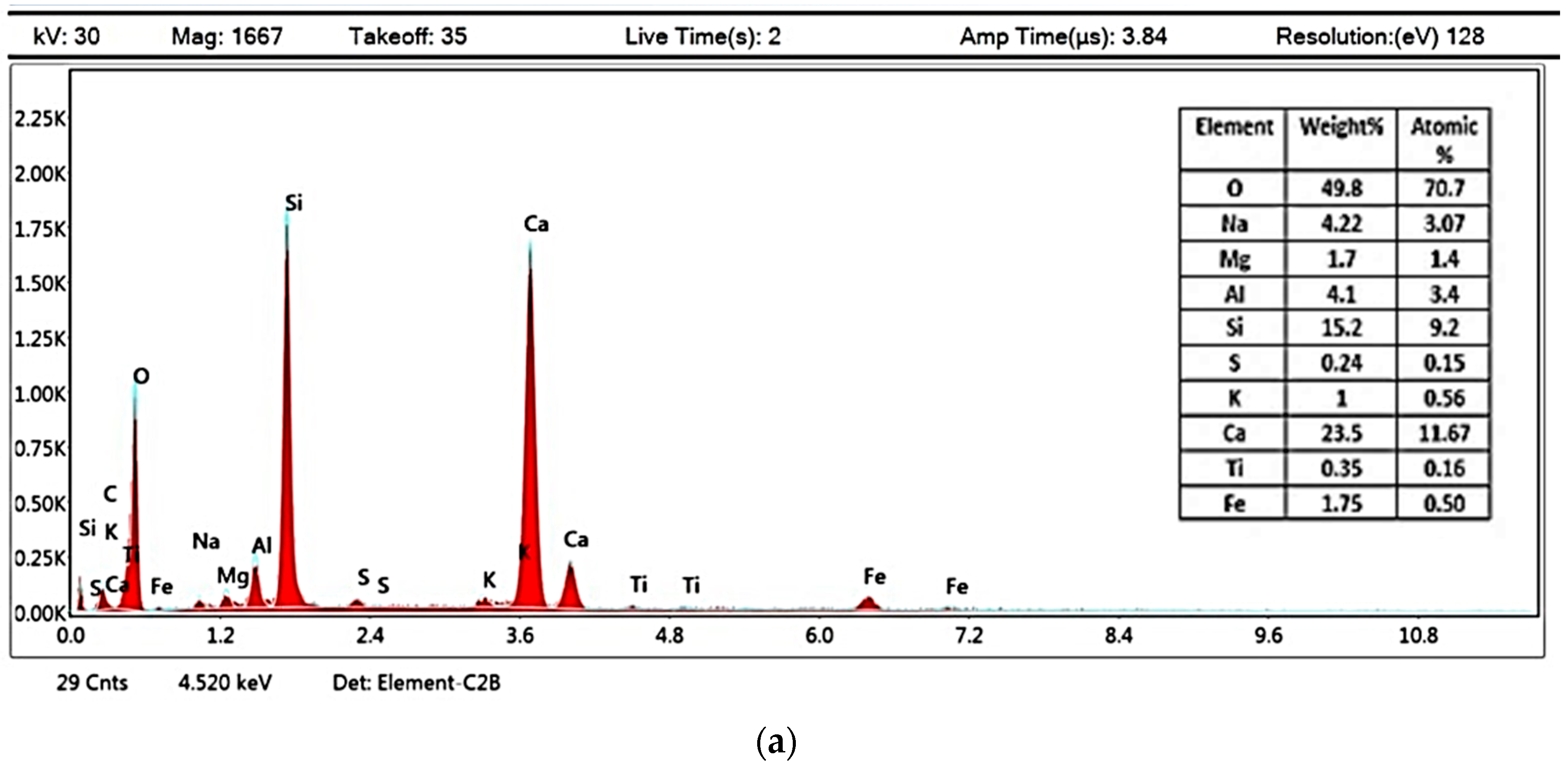

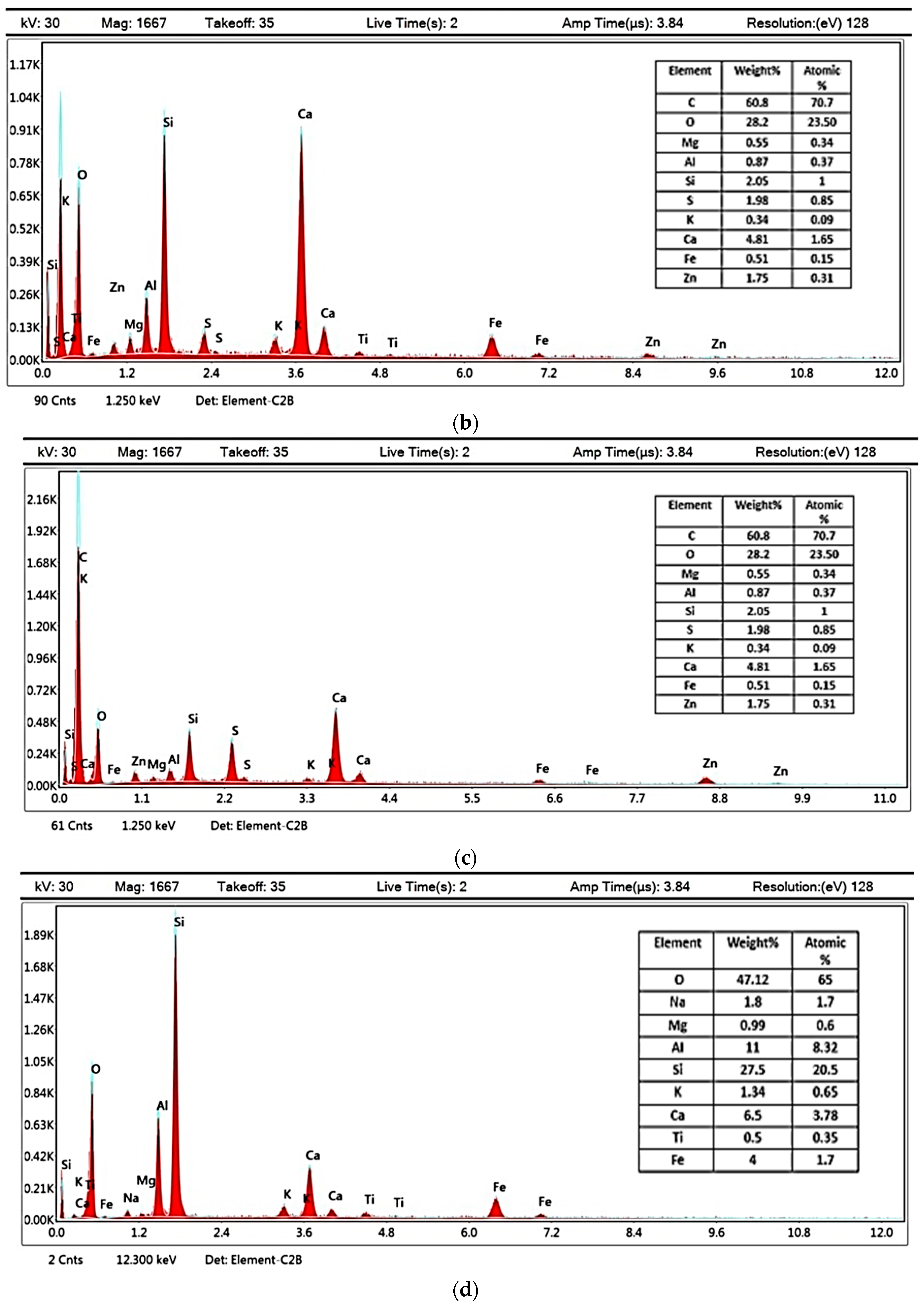

3.7. EDX Analysis

3.8. Sustainability Assessment

3.8.1. CO2 Emission Reduction

3.8.2. Cost Saving

3.9. Scalability Considerations

4. Conclusions

- The workability of IPBs was significantly affected by material additions, where untreated CR reduced slump by 39.5% at 20% sand replacement, while physically treated CR improved slump values by 9–15.4% at the same level. Increased CP and GP contents caused progressive reductions in slump by 27.9–38.4% and 26.7–41.8%, respectively, across 10–30% replacement ratios.

- Untreated CR reduced compressive strength by 11.6% and 37.6% at 10% and 20% replacement, respectively. CP and GP treatments improved strength by 27.6% and 18.3% compared to untreated CR, and 20% cement replacement with CP and GP increased strength by 17.3% and 5.1%. BF enhanced strength up to 0.6%, while GF (0.6%) had negligible effect and PP showed slight improvement. At 20% sand replacement, untreated CR increased flexural strength by 16%, while treatment with CP and GP further enhanced the improvement to 18% and 17%, respectively. replacing 20% of cement with CP or GP significantly enhanced mechanical performance, with CP showing superior gains.

- Water absorption across all mixes remained below 10%, with the addition of 10% and 20% untreated CR increasing absorption by 34% and 38.3%, respectively. Treated CR using CP or GP reduced absorption—particularly with CP. Among fibers, PP fibers at 0.6% showed the lowest absorption (3.70%), followed by BF (4–6%) and GF (4%).

- Abrasion resistance of IPBs was markedly improved by rubber addition, ceramic treatment, and fiber reinforcement. The best results were obtained with 20% rubber (CR20), ceramic-treated rubber (TR20CP), 20% ceramic powder replacement, and 0.6% polypropylene fibers, confirming their potential to enhance durability and sustainability of paving blocks.

- Microstructural observations confirmed that untreated CR led to weak interfacial bonding and increased porosity, compromising matrix integrity. In contrast, CR treated with CP showed a denser structure with improved ITZ characteristics. CP outperformed GP in reducing voids and enhancing particle packing. Additionally, BF and PP fibers further improved cohesion and reduced micro-defects, contributing to the observed durability and strength enhancements.

- In addition to the mechanical and durability enhancements, a preliminary sustainability assessment demonstrated that the proposed IPBs incorporating CP, GP, CR, and recycled ceramic aggregates achieved a reduction of approximately 25% in embodied CO2 emissions and ~20% in raw material costs compared to conventional paving blocks. These findings highlight not only the technical feasibility but also the environmental and economic advantages of the proposed approach, reinforcing its potential for sustainable large-scale application.

5. Limitations and Future Scope

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patil, A.R.; Sathe, S.B. Feasibility of sustainable construction materials for concrete paving blocks: A review on waste foundry sand and other materials. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 1552–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Cui, H.; Poon, C.S. Assessment of in-situ alkali-silica reaction (ASR) development of glass aggregate concrete prepared with dry-mix and conventional wet-mix methods by X-ray computed micro-tomography. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 90, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, P.; Priastiwi, Y.A. Testing of Concrete Paving Blocks the BS EN 1338: 2003 British and European Standard Code. Teknik 2008, 29, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad, H.M.; Bolong, N.; Saad, I.; Gungat, L.; Tioon, J.; Pileh, R.; Delton, M.J. Manufacture of concrete paver block using waste materials and by-products: A review. GEOMATE J. 2022, 22, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, A.; Acharya, P.K.; Manaye, N.; Das, A.K. Waste incorporation in paver block production. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 93, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssf, O.; Elgawady, M. An overview of sustainable concrete made with scrap rubber. In Proceedings of the 22nd Australasian Conference on the Mechanics of Structures and Materials, ACMSM, ACMSM, Sydney, Australia, 11–14 December 2012; Volume 2013, pp. 1039–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Swilam, A.; Tahwia, A.M.; Youssf, O. Effect of rubber heat treatment on rubberized-concrete mechanical performance. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zaman, I.; Hannam, J.R.; Kapota, S.; Luong, L.; Youssf, O.; Ma, J. Improvement of adhesive toughness measurement. Polym. Test. 2011, 30, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, K.A.; Tahwia, A.M.; Youssf, O. Performance of eco-friendly ECC made of pre-treated crumb rubber and waste quarry dust. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, B.S. Structural behavior and m–k value of composite slab utilizing concrete containing crumb rubber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda Taha, M.M.; El-Dieb, A.S.; Abd El-Wahab, M.A.; Abdel-Hameed, M.E. Mechanical, fracture, and microstructural investigations of rubber concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2008, 20, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Srivastava, A.; Bhunia, D. An investigation on effect of partial replacement of cement by waste marble slurry. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 134, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, Q.; Wei, J.; Zhang, T. Structural characteristics and hydration kinetics of modified steel slag. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-H.; Huang, F.; Liu, R.; Hou, J.-L.; Li, G.-L. Test research on effects of waste ceramic polishing powder on the permeability resistance of concrete. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, N.; Saleh, R.D.; Yakoob, N.B.; Banyhussan, Q.S. Utilization of ceramic waste powder in cement mortar exposed to elevated temperature. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2021, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Parekh, D. Valorization of ceramic waste powder as cementitious blend in self-compacting concrete–A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 77, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazenan, P.N.; Khalid, F.S.; Shahidan, S.; Shamsuddin, S.-M. Review of palm oil fuel ash and ceramic waste in the production of concrete. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Busan, Republic of Korea, 25–27 August 2017; p. 012051. [Google Scholar]

- Suraneni, P.; Burris, L.; Shearer, C.R.; Hooton, R.D. ASTM C618 fly ash specification: Comparison with other specifications, shortcomings, and solutions. ACI Mater. J. 2021, 118, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabdo, A.A.; Abd Elmoaty, M.; Aboshama, A.Y. Utilization of waste glass powder in the production of cement and concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 124, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahwia, A.M.; Helal, K.A.; Youssf, O. Chopped basalt fiber-reinforced high-performance concrete: An experimental and analytical study. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ali, M. Development and Engineering Evaluation of Interlocking Hollow Blocks Made of Recycled Plastic for Mortar-Free Housing. Buildings 2025, 15, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibiina, R.H.; Biira, S.; Amabayo, E.B.; Akoba, R. Performance evaluation of the paving blocks moulded with plastic waste as a binding material. Discov. Environ. 2025, 3, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Fan, K.; Wu, F.; Chen, D. Experimental study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of chopped basalt fibre reinforced concrete. Mater. Des. 2014, 58, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitkus, A.; Gražulytė, J.; Šernas, O.; Karbočius, M.; Mickevič, R. Concrete modular pavement structures with optimized thickness based on characteristics of high performance concrete mixtures with fibers and silica fume. Materials 2021, 14, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, B.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, M. Experimental investigation on physical properties of concrete containing polypropylene fiber and water-borne epoxy for pavement. Coatings 2023, 13, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, M.; Nejad, F.M.; Sobhani, J.; Chini, M. Mechanical and durability properties of fiber reinforced concrete overlay: Experimental results and numerical simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 268, 121083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Savio, A.A.; Esquivel, D.L.T.; Silva, F.d.A.; Pastor, J.A. Influence of synthetic fibers on the flexural properties of concrete: Prediction of toughness as a function of volume, slenderness ratio and elastic modulus of fibers. Polymers 2023, 15, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 197-1; Standard Cement-Part 1: Composition, Specification, and Conformity Criteria Common Cements. ASRO: Bucharest, Romania, 2011.

- ASTM C33; Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates. American Society for Testing and Materials: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003.

- Xiong, Z.; Tang, Z.; He, S.; Fang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Liu, F.; Li, L. Analysis of mechanical properties of rubberised mortar and influence of styrene–butadiene latex on interfacial behaviour of rubber–cement matrix. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 300, 124027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM-C143; Standard Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic Cement Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1996.

- Jeon, I.K.; Qudoos, A.; Woo, B.H.; Yoo, D.H.; Kim, H.G. Effects of nano-silica and reactive magnesia on the microstructure and durability performance of underwater concrete. Powder Technol. 2022, 398, 116976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.M.F.; Ayub, T.; Khan, S.U.; Rafeeqi, S.F.A. Investigation of the physical properties of expanded shale aggregate and its influence on the mechanical properties of OPC and LC3-50-based concretes. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almawla, S.A.; Mohammed, M.K.; Al-Hadithi, A.I.; Dawson, A.R. Evaluation and optimization of volume fraction and aspect ratio of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) fibers in self-compacting lightweight concrete. J. Struct. Integr. Maint. 2024, 9, 2314823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleng, M.; Kanali, C.; Gariy, Z.C.A.; Ronoh, E. Physical and Mechanical Experimental Investigation of Concrete Incorporated with Ceramic and Porcelain Clay Tile Powders as Partial Cement Substitutes. Int. J. Eng. Res. 2018, 7, 126–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kasinikota, P.; Tripura, D.D. Effects of coir fibres and cement addition on properties of hollow interlocking compressed earth blocks. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2023, 8, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, D.M.; Aboubakr, S.H.; El-Dieb, A.S.; Reda Taha, M.M. High performance concrete incorporating ceramic waste powder as large partial replacement of Portland cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 144, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahwia, A.M.; Essam, A.; Tayeh, B.A.; Elrahman, M.A. Enhancing sustainability of ultra-high performance concrete utilizing high-volume waste glass powder. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafei, B.; Kazemian, M.; Dopko, M.; Najimi, M. State-of-the-art review of capabilities and limitations of polymer and glass fibers used for fiber-reinforced concrete. Materials 2021, 14, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Huang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Chen, D. Effect of polypropylene and basalt fiber on the behavior of mortars for repair applications. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2016, 5927609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganjian, E.; Khorami, M.; Maghsoudi, A.A. Scrap-tyre-rubber replacement for aggregate and filler in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 1828–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmonem, A.; El-Feky, M.; Nasr, E.-S.A.; Kohail, M. Performance of high strength concrete containing recycled rubber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 116660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Jiao, Y.; Sha, T. Experimental investigation of the mechanical and durability properties of crumb rubber concrete. Materials 2016, 9, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldin, N.N.; Senouci, A.B. Measurement and prediction of the strength of rubberized concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 1994, 16, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polydorou, T.; Constantinides, G.; Neocleous, K.; Kyriakides, N.; Koutsokeras, L.; Chrysostomou, C.; Hadjimitsis, D. Effects of pre-treatment using waste quarry dust on the adherence of recycled tyre rubber particles to cementitious paste in rubberised concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 254, 119325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, W.; You, Q.; Chen, M.; Zeng, Q. Waste ceramic powder as a pozzolanic supplementary filler of cement for developing sustainable building materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareei, S.A.; Ameri, F.; Shoaei, P.; Bahrami, N. Recycled ceramic waste high strength concrete containing wollastonite particles and micro-silica: A comprehensive experimental study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 201, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Gu, Q.; Tian, S.; Gao, X.; Liu, Y.; Sun, B.; Wang, X. Flexural fatigue behavior of hooked-end steel fibres reinforced concrete using centrally loaded round panel test. Mater. Struct. 2023, 56, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Gu, Q.; Gao, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tian, S.; Ruan, Z.; Huang, J. Effect of basalt fibers and silica fume on the mechanical properties, stress-strain behavior, and durability of alkali-activated slag-fly ash concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 418, 135440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; Ren, L.; Tian, S.; Liu, X.; Zhong, Z.; Deng, Z.; Yan, R. Study on the fracture toughness of polypropylene–basalt fiber-reinforced concrete. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2021, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama, D.M.A.; Cuaspud, J.A.G.; Taniolo, N.; Boccaccini, A.R. Glass-ceramic materials obtained by sintering of vitreous powders from industrial waste: Production and properties. Constr. Mater. 2021, 1, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.-Y.; Chen, A.-J.; Liu, H.-D. Effect of waste tire rubber particles on concrete abrasion resistance under high-speed water flow. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2021, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chai, J.; Wang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Tong, X. A review of the durability-related features of waste tyre rubber as a partial substitute for natural aggregate in concrete. Buildings 2022, 12, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnaby, A.T.; El-Sayed, A.A.E.-G.M.; Mostafa, A.E.A. Producing Environmentally Sustainable and Wear-Resistant Rigid Pavement Utilizing Glass Powder. Eng. Res. J. 2025, 184, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | CEM I 42.5N | Ceramic Powder (CP) | Glass Powder (GP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na2O | 1.377 | 1.900 | 0.054 |

| MgO | 2.498 | 0.948 | 0.052 |

| Al2O3 | 6.791 | 20.087 | 0.752 |

| SiO2 | 23.802 | 58.491 | 98.885 |

| P2O5 | 0.112 | 0.336 | 0.014 |

| SO3 | 5.480 | 0.676 | 0.036 |

| K2O | 0.398 | 1.914 | 0.018 |

| CaO | 49.045 | 1.391 | 0.078 |

| TiO2 | 0.816 | 1.196 | 0.038 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.056 | 0.043 | - |

| Fe2O3 | 6.837 | 5.627 | 0.042 |

| MnO | 0.284 | 0.029 | - |

| Zno | 0.009 | 0.007 | - |

| Sro | 0.066 | 0.020 | - |

| Zro2 | 0.023 | 0.039 | 0.017 |

| Cl | 0.105 | 0.188 | 0.014 |

| L.O.I | 2.3 | 7.1 | - |

| Fiber Type | Length (mm) | Diameter (mm) | Density (gm/cm3) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BF | 12.7 | 0.015 | 2.6 | 2600 | 85 |

| PP | 12.0 | 0.038 | 0.9 | 350 | 3.5 |

| GF | 12.0 | 0.015 | 2.5 | 1300 | 70 |

| Variable Applied | Mix Code | Binder | Fine Aggregate | Coarse Aggregate | Fibers | Water | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | GP | CP | Sand | Rubber | Dolomite | Recycled Ceramic | BF | GF | PP | |||

| Control mix | CC | 325 | 0 | 0 | 650 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 |

| Untreated CR replaces sand | CR10 | 325 | 0 | 0 | 584 | 23.8 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 |

| CR20 | 325 | 0 | 0 | 519 | 47.5 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 | |

| Treated CR replaces sand | TR20CP | 325 | 0 | 0 | 519 | 47.5 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 |

| TR20GP | 325 | 0 | 0 | 519 | 47.5 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 | |

| CP replaces cement | CP10 | 292 | 0 | 24.7 | 650 | 0 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 |

| CP20 | 259 | 0 | 49.5 | 650 | 0 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 | |

| CP30 | 227 | 0 | 74.2 | 650 | 0 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 | |

| GP replaces cement | GP10 | 292 | 26.8 | 0 | 650 | 0 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 |

| GP20 | 259 | 53.6 | 0 | 650 | 0 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 | |

| GP30 | 227 | 80.3 | 0 | 650 | 0 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 | |

| BF reinforcement | BF0.3 | 325 | 0 | 0 | 650 | 0 | 0 | 1300 | 7.8 | 0 | 0 | 162 |

| BF0.6 | 325 | 0 | 0 | 650 | 0 | 0 | 1300 | 15.6 | 0 | 0 | 162 | |

| BF1 | 325 | 0 | 0 | 650 | 0 | 0 | 1300 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 162 | |

| GF reinforcement | GF0.6 | 325 | 0 | 0 | 650 | 0 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 15.6 | 0 | 162 |

| PP reinforcement | PP0.6 | 325 | 0 | 0 | 650 | 0 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 0 | 5.46 | 162 |

| Mix Code | Slump (mm) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Water Absorption (wt%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 Days | 28 Days | ||||

| CC | 86 | 37.3 | 43.0 | 5.0 | 4.7 |

| CR10 | 65 | 29.7 | 38.2 | 5.7 | 6.3 |

| CR20 | 52 | 17.8 | 26.8 | 5.8 | 6.5 |

| TR20CP | 60 | 26.8 | 34.2 | 5.9 | 3.5 |

| TR20GP | 55 | 22.0 | 31.7 | 5.9 | 4.2 |

| CP10 | 62 | 30.8 | 40.0 | 5.3 | 4.5 |

| CP20 | 60 | 35.5 | 50.4 | 6.0 | 3.0 |

| CP30 | 53 | 28.5 | 36.7 | 5.5 | 4.7 |

| GP10 | 66 | 26.3 | 32.1 | 5.3 | 5.2 |

| GP20 | 55 | 32.4 | 45.2 | 5.7 | 6.0 |

| GP30 | 50 | 21.1 | 30.4 | 5.2 | 7.2 |

| BF0.3 | 65 | 31.6 | 45.0 | 6.2 | 4.3 |

| BF0.6 | 60 | 41.0 | 49.0 | 6.5 | 4.0 |

| BF1 | 50 | 33.8 | 39.0 | 5.7 | 6.0 |

| GF0.6 | 50 | 38.0 | 43.2 | 5.1 | 4.0 |

| PP0.6 | 50 | 39.7 | 47.0 | 5.5 | 3.7 |

| Mix | Initial Mass (g) | Final Mass (g) | Mass Loss (g) | Mass Loss % | Abrasion Depth (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 250 | 237 | 12.7 | 5.08 | 0.80 |

| CR10 | 265 | 259 | 5.7 | 2.15 | 0.52 |

| CR20 | 229 | 224 | 4.7 | 2.07 | 0.40 |

| TR20CP | 206 | 201 | 4.2 | 2.04 | 0.28 |

| TR20GP | 227 | 223 | 4.6 | 2.02 | 0.32 |

| CP10 | 221 | 210 | 11.0 | 4.99 | 0.70 |

| CP20 | 230 | 217 | 11.2 | 4.87 | 0.69 |

| CP30 | 225 | 212 | 13.0 | 5.79 | 0.72 |

| GP10 | 221 | 210 | 9.4 | 4.25 | 0.74 |

| GP20 | 240 | 228 | 12.0 | 5.00 | 0.69 |

| GP30 | 240 | 226 | 13.0 | 5.41 | 0.77 |

| BF0.3 | 228 | 220 | 7.9 | 3.49 | 0.76 |

| BF0.6 | 227 | 220 | 7.6 | 3.34 | 0.72 |

| BF1 | 245 | 230 | 14.8 | 6.04 | 1.02 |

| GF0.6 | 239 | 229 | 10.0 | 4.19 | 0.60 |

| PP0.6 | 232 | 227 | 5.3 | 2.28 | 0.76 |

| Mix Type | CO2 Emissions (kg/m3) | Reduction (%) | Material Cost (USD/m3) | Cost Saving (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (CC) | 380–400 | – | 72 | – |

| Modified (20% CP + CR + ceramic agg.) | 280–300 | 25–27% | 58–60 | 18–20% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tajuldeen, I.; Tahwia, A.M.; Youssf, O. Performance Evaluation of Fiber-Reinforced Rubberized Paving-Blocks Containing Ceramic and Glass Wastes. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10110298

Tajuldeen I, Tahwia AM, Youssf O. Performance Evaluation of Fiber-Reinforced Rubberized Paving-Blocks Containing Ceramic and Glass Wastes. Infrastructures. 2025; 10(11):298. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10110298

Chicago/Turabian StyleTajuldeen, Ibrahim, Ahmed M. Tahwia, and Osama Youssf. 2025. "Performance Evaluation of Fiber-Reinforced Rubberized Paving-Blocks Containing Ceramic and Glass Wastes" Infrastructures 10, no. 11: 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10110298

APA StyleTajuldeen, I., Tahwia, A. M., & Youssf, O. (2025). Performance Evaluation of Fiber-Reinforced Rubberized Paving-Blocks Containing Ceramic and Glass Wastes. Infrastructures, 10(11), 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10110298