Qualitative Analysis of Micro-System-Level Factors Determining Sport Persistence

Abstract

1. Introduction

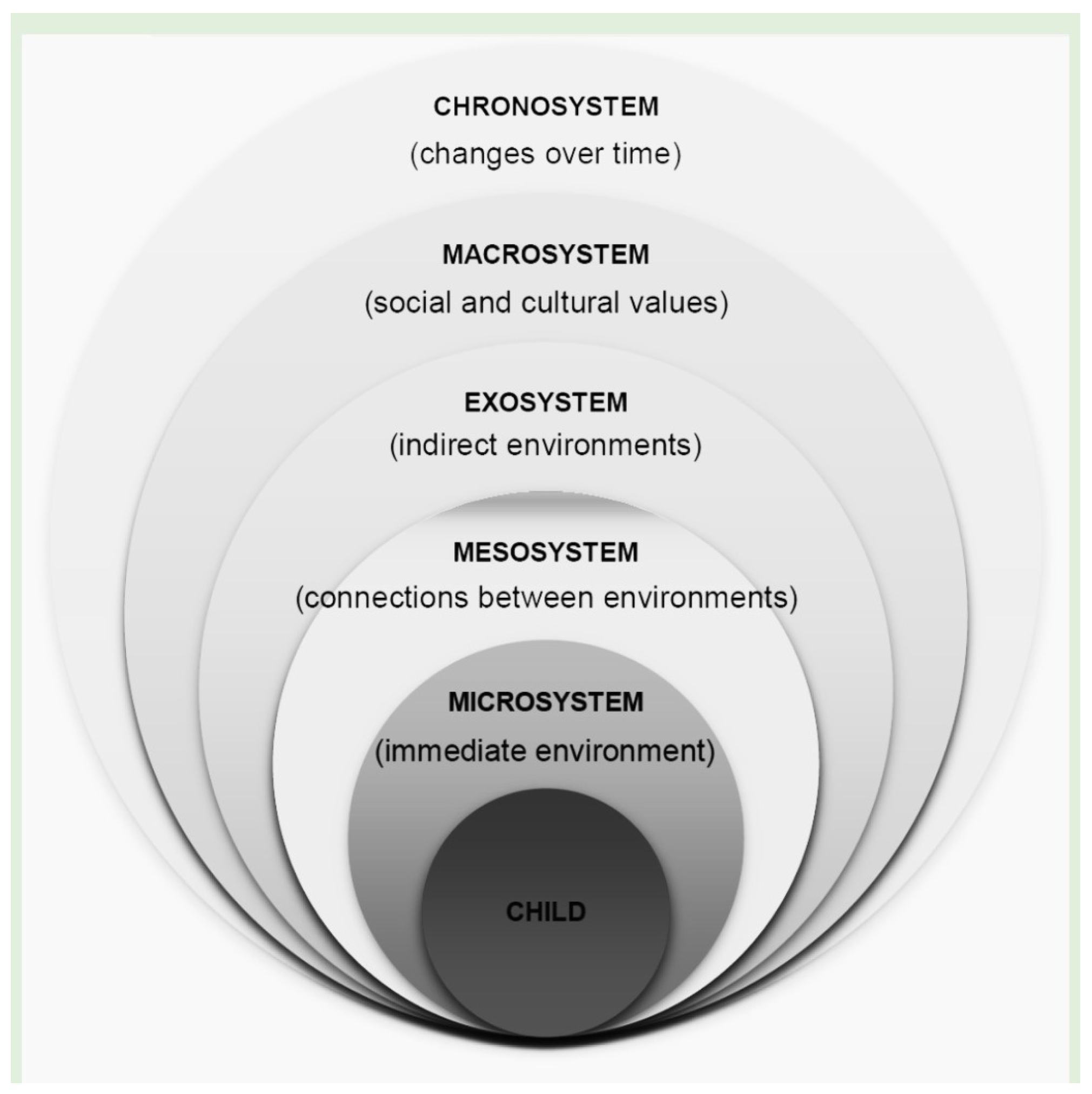

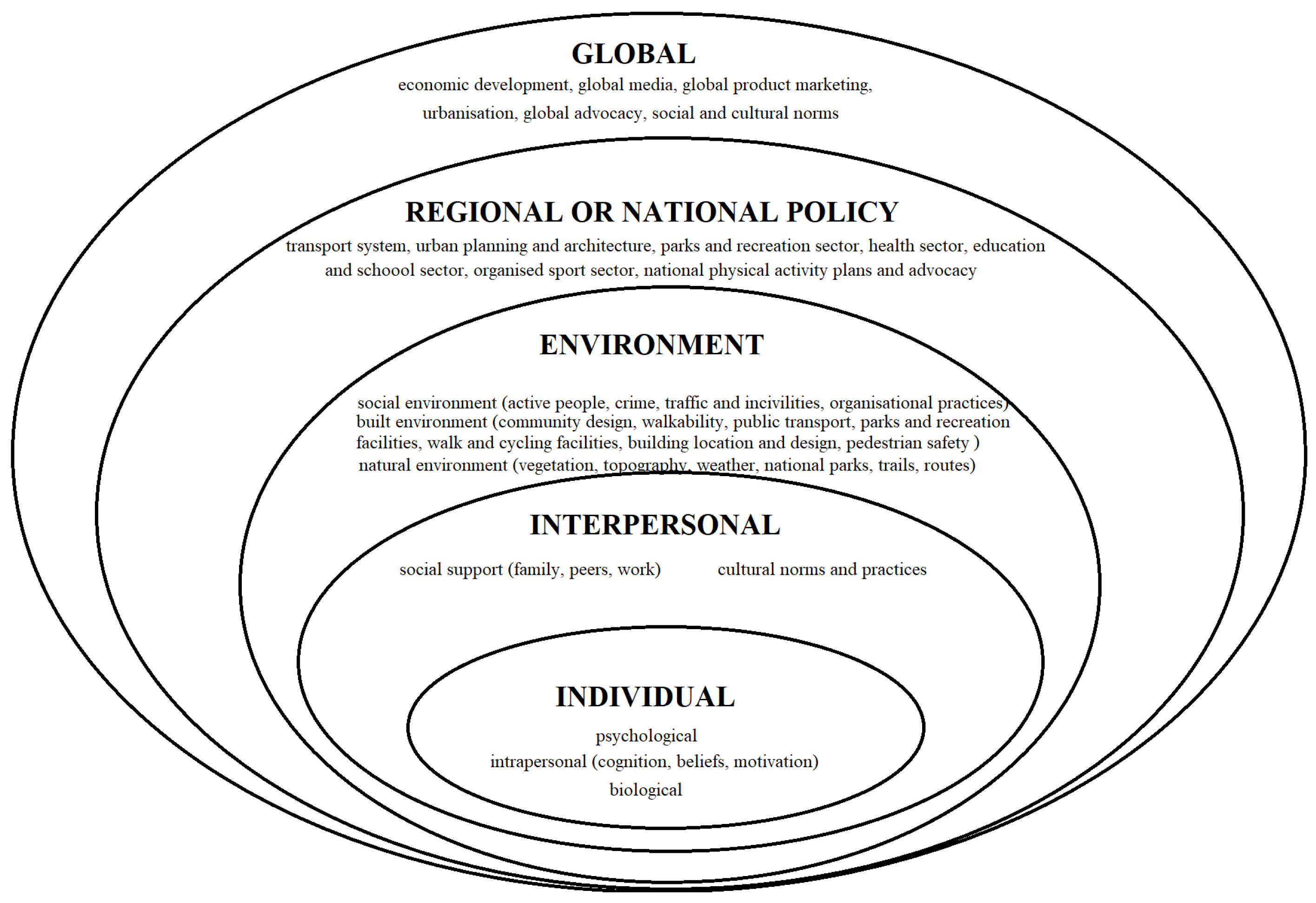

- Individual level: age, gender, gender orientation, physical characteristics (weight, height, BMI), physical health (illnesses), mental health (health awareness and behaviour, risk-taking behaviour, anxiety, coping, resilience, well-being, religious/spiritual well-being, sense of coherence, self-efficacy, future orientation, burnout, loneliness), other activities (educational career, employment);

- Microsystem: family characteristics (family structure, number of siblings, sibling order, parental employment, socio-economic status and well-being, family attachment and relationships, family social relations), friend characteristics (strength, type, quality, nature of), sports environment (relationship with sports partners, relationship with coaches, training characteristics, relationship with clubs and institutional climate);

- Mesosystem: family–school relationship, peer–parent relationship, family–school–peer triangle;

- Macrosystem: social trends, political trends and regulations, cultural characteristics and values.

2. Presentation of the Research

2.1. Sample

2.2. Methods

- Phase 1: definition of the sample (the head of the research group, based on the research project and its plan, detected the potential sample);

- Phase 2: validation of the interview script (all members were asked to think through the potential interview questions, then a discussion was carried out in a research group meeting);

- Phase 3: application of the interviews (all members were involved in the interview process, including recruitment and application as well);

- Phase 4: transcription and analysis (five research group members [HC, RP, HLT, OCsK, CsL] were involved in the preparation of the transcripts and seven in the analysis [BTSJ, RB, ZsL, BTT, BL, MK, KEK]);

- Phase 5: coding and categorisation (Seven research group members [BTSJ, RB, ZsL, BTT, BL, MK, KEK] were involved in the creation of codes. In the initial stage, the analysis involved the identification and coding of incidents. Afterwards, the preliminary codes were compared with other codes, and the codes were grouped into categories. The incidents within each category were then compared with those in other categories. Then, the future codes and categories were compared. Subsequently, the new data were subjected to comparison with the information that had been collected at an earlier stage of the analysis.);

- Phase 6: interpretation (all members were asked to support the interpretation of the results).

3. Results

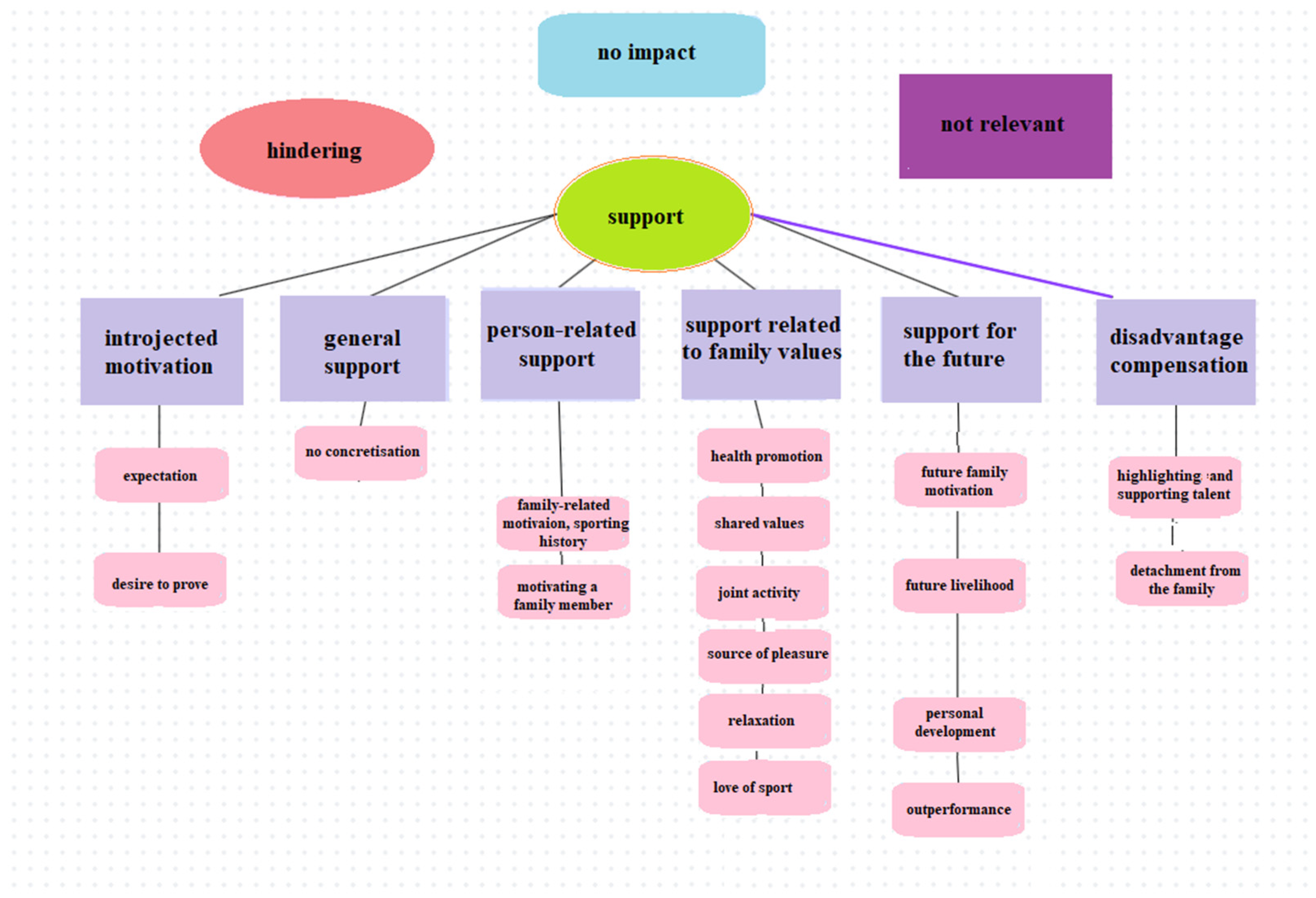

3.1. Family-Related Impact

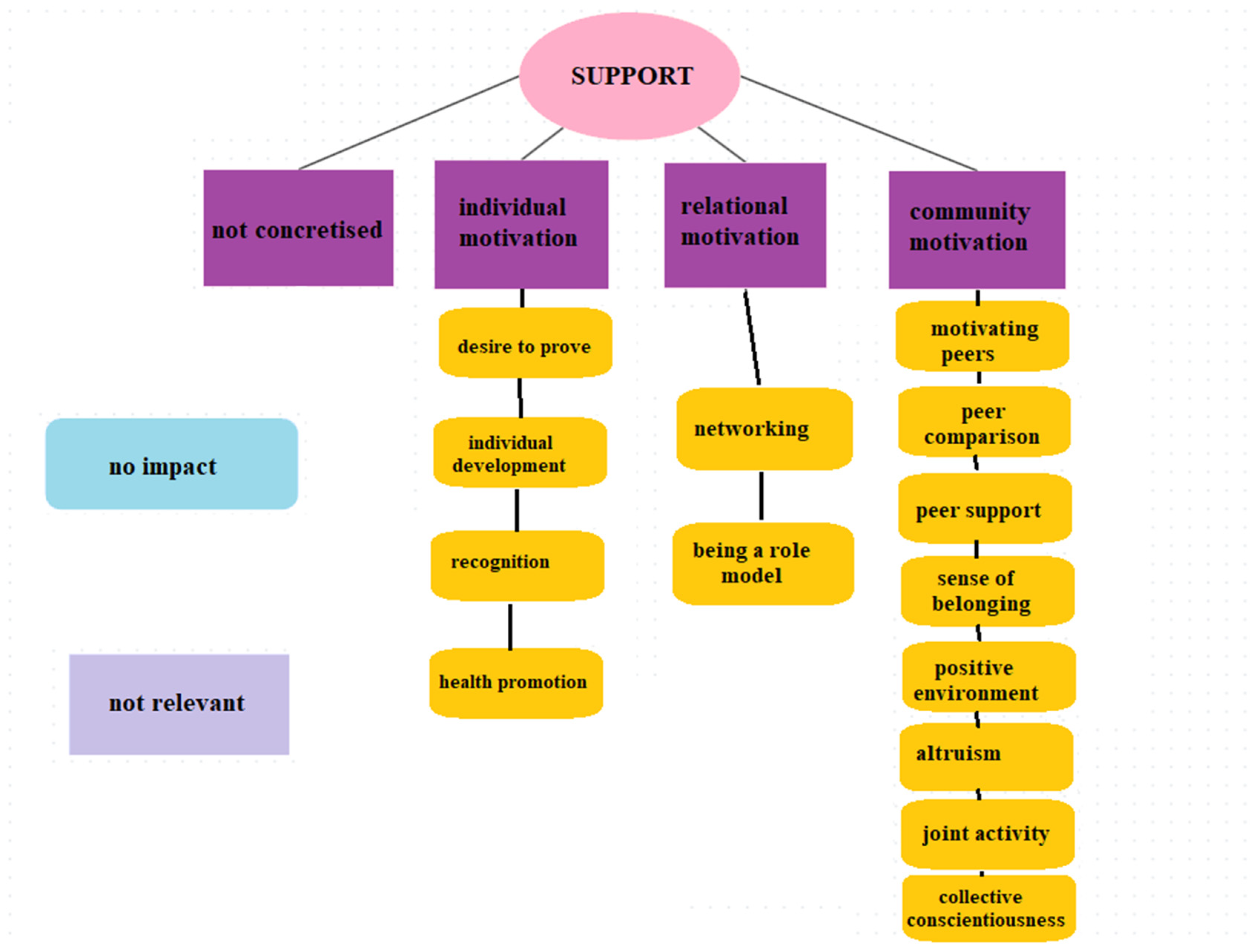

3.2. Peer Influence

3.3. The Impact of the Coach

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kovács, K.E. A sportperzisztencia vizsgálata az egészség, kapcsolati háló, motiváció és tanulmányi eredményesség függvényében. Iskolakultúra 2021, 31, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero, O.; Salguero, A.; Tuero, C.; Alvarez, E.; Marquez, S. Dropout Reasons in Young Spanish Athletes: Relationship to Gender, Type of Sport and Level of Competition. J. Sport Behav. 2006, 29, 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser-Thomas, J.; Côté, J.; Deakin, J. Understanding Dropout and Prolonged Engagement in Adolescent Competitive Sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandbu, Å.; Bakken, A.; Sletten, M.A. Exploring the Minority–Majority Gap in Sport Participation: Different Patterns for Boys and Girls? Sport Soc. 2019, 22, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, S.A.; Cliff, D.P.; Okely, A.D. Socio-Ecological Predictors of Participation and Dropout in Organised Sports during Childhood. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoni, C.; Pesce, C.; Cherubini, D. Early Drop-Out from Sports and Strategic Learning Skills: A Cross-Country Study in Italian and Spanish Students. Sports (2075-4663) 2021, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, A.E.; Reis, R.S.; Sallis, J.F.; Wells, J.C.; Loos, R.J.; Martin, B.W. Correlates of Physical Activity: Why Are Some People Physically Active and Others Not? Lancet 2012, 380, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.M.; Siegel, J.T. Youth Sports and Physical Activity: The between Perceptions of Childhood Sport Experience and Adult Exercise Behavior. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2017, 33, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, E.; Petrie, T.A.; Moore, E.W.G. The Relationship of Motivational Climates, Mindsets, and Goal Orientations to Grit in Male Adolescent Soccer Players. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 19, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, K.E.; Szakál, Z. Factors Influencing Sport Persistence Still Represent a Knowledge Gap—The Experience of a Systematic Review. BMC Psychol. 2024; under review. [Google Scholar]

- Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M.A. The Role of Passion for Sport in College Student-Athletes’ Motivation and Effort in Academics and Athletics. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2021, 2, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, M.; Gaudreau, P.; Franche, V. Perception of Coaching Behaviors, Coping, and Achievement in a Sport Competition. J Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2011, 33, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, C.; Topa, G. Leadership and Motivational Climate: The Relationship with Objectives, Commitment, and Satisfaction in Base Soccer Players. Behav. Sci. (2076-328X) 2019, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillet, E.; Sarrazin, P.; Carpenter, P.J.; Trouilloud, D.; Cury, F. Predicting Persistence or Withdrawal in Female Handballers with Social Exchange Theory. Int. J. Psychol. 2002, 37, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, K.E. Toward the Pathway of Sports School Students: Health Awareness and Dropout as the Index of Academic and Non-Academic Achievement. Hung. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 9, 730–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Eime, R.; Westerbeek, H. Community Sports Clubs: Are They Only about Playing Sport, or Do They Have Broader Health Promotion and Social Responsibilities? Ann. Leis. Res. 2019, 22, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G. More Grounded Theory Methodology: A Reader; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (5. Paperback Print); Aldine Transaction: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, B. Az Ifjúság Viszonya Az Értékek Világához. In Ifjúság 2000; Tanulmányok, I., Szabó, A., Bauer, B., Laki, L., Eds.; Nemzeti Ifjúságkutató Intézet: Budapest, Hungary, 2002; pp. 202–219. Available online: https://www.antikvarium.hu/konyv/gazso-tibor-bauer-bela-ifjusag-2000-tanulmanyok-i-452249-0 (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Rennie, D.L. Grounded Theory Methodology as Methodical Hermeneutics: Reconciling Realism and Relativism. Theory Psychol. 2000, 10, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructivist Grounded Theory. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 299–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Jones, J.; Turunen, H.; Snelgrove, S. Theme Development in Qualitative Content Analysis and Thematic Analysis. JNEP 2016, 6, p100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Managing Quality in Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-5297-1664-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, K.; Oláh, Á.J.; Pusztai, G. The Role of Parental Involvement in Academic and Sports Achievement. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Chee, C.S.; Norjali Wazir, M.R.W.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; Wang, T. The Role of Parents in the Motivation of Young Athletes: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol 2024, 14, 1291711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Gostian-Ropotin, L.A.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Belando-Pedreño, N.; Simón, J.A.; López-Mora, C.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Sporting Mind: The Interplay of Physical Activity and Psychological Health. Sports 2024, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremer-Sadlik, T.; Kim, J.L. Lessons from Sports: Children’s Socialization to Values through Family Interaction during Sports Activities. Discourse Soc. 2007, 18, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisinskiene, A.; Lochbaum, M. A Qualitative Study Examining Parental Involvement in Youth Sports over a One-Year Intervention Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, T.; Spaaij, R. The Mediating Effects of Family on Sport in International Development Contexts. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2012, 47, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.; Young, J.; Harvey, J.; Payne, W. Psychological and Social Benefits of Sport Participation: The Development of Health through Sport Conceptual Model. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2013, 16, e79–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connaughton, D.; Wadey, R.; Hanton, S.; Jones, G. The Development and Maintenance of Mental Toughness: Perceptions of Elite Performers. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, K.; Bogner, L.; Sander, K.; Reuß, K. Sport for a Livelihood and Well-Being: From Leisure Activity to Occupational Devotion. Int. J. Sociol. Leis. 2022, 5, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonavolontà, V.; Cataldi, S.; Latino, F.; Carvutto, R.; De Candia, M.; Mastrorilli, G.; Messina, G.; Patti, A.; Fischetti, F. The Role of Parental Involvement in Youth Sport Experience: Perceived and Desired Behavior by Male Soccer Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordalen, G.; Lemyre, P.-N.; Durand-Bush, N. Interplay of Motivation and Self-Regulation throughout the Development of Elite Athletes. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2020, 12, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.M.; Graf, M.; Bilalić, M. Never Too Much—More Talent in Football (Always) Leads to More Success. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0290147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, J.; Zakus, D.H.; Cowell, J. Development through Sport: Building Social Capital in Disadvantaged Communities. Sport Manag. Rev. 2008, 11, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminen, K.A.; Holt, N.L. Adolescent Athletes’ Learning about Coping and the Roles of Parents and Coaches. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2012, 13, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malm, C.; Jakobsson, J.; Isaksson, A. Physical Activity and Sports—Real Health Benefits: A Review with Insight into the Public Health of Sweden. Sports 2019, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakalidis, K.E.; Menting, S.G.P.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T.; Hettinga, F.J. The Role of the Social Environment in Pacing and Sports Performance: A Narrative Review from a Self-Regulatory Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res Public Health 2022, 19, 16131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacón Cuberos, R.; Zurita Ortega, F.; Puertas Molero, P.; Knox, E.; Cofré Bolados, C.; Viciana Garófano, V.; Muros Molina, J.J. Relationship between Healthy Habits and Perceived Motivational Climate in Sport among University Students: A Structural Equation Model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, R.J. How Coaches, Parents, and Peers Influence Motivation in Sport. Front. Young Minds 2022, 10, 685862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M.J.; Coffee, P.; Barker, J.B.; Evans, A.L. Promoting Shared Meanings in Group Memberships: A Social Identity Approach to Leadership in Sport. Reflective Pract. 2014, 15, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.H.; Kee, Y.H.; Chen, M.-Y. Why Grateful Adolescent Athletes Are More Satisfied with Their Life: The Mediating Role of Perceived Team Cohesion. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 124, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, S.; Dixon, M.A. Understanding Sense of Community From the Athlete’s Perspective. J. Sport Manag. 2011, 25, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, C.; Bosshard, A.; Whitmarsh, L. Motivation and Climate Change: A Review. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, K.E. Egészség És Tanulás a Köznevelési Típusú Sportiskolákban; CHERD: Debrecen, Hungary, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Foulds, S.J.; Hoffmann, S.M.; Hinck, K.; Carson, F. The Coach–Athlete Relationship in Strength and Conditioning: High Performance Athletes’ Perceptions. Sports 2019, 7, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olympiou, A.; Jowett, S.; Duda, J.L. The Psychological Interface between the Coach-Created Motivational Climate and the Coach-Athlete Relationship in Team Sports. Sport Psychol. 2008, 22, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.D.; Vargas-Tonsing, T.M.; Feltz, D.L. Coaching Efficacy in Intercollegiate Coaches: Sources, Coaching Behavior, and Team Variables. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2005, 6, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.; Carpenter, C.; Fink, J.; Baker, R. Benefits of Altruistic Leadership in Intercollegiate Athletics: An Examination of Coaches’ Perspectives. J. Study Sports Athl. Educ. 2008, 2, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborde, S.; Guillén, F.; Watson, M.; Allen, M.S. The Light Quartet: Positive Personality Traits and Approaches to Coping in Sport Coaches. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2017, 32, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageau, G.A.; Vallerand, R.J. The Coach–Athlete Relationship: A Motivational Model. J. Sports Sci. 2003, 21, 883–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, J.; Gilbert, W. An Integrative Definition of Coaching Effectiveness and Expertise. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2009, 4, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| male | 80 | 60.2 |

| female | 53 | 39.8 |

| Mother’s education | ||

| primary | 10 | 7.5 |

| secondary | 71 | 53.4 |

| higher level | 52 | 39.1 |

| Father’s education | ||

| primary | 11 | 8.3 |

| secondary | 81 | 60.9 |

| higher level | 41 | 30.8 |

| Own level of education | ||

| secondary | 85 | 63.9 |

| tertiary | 48 | 36.1 |

| Type of sport | ||

| team sports | 82 | 61.7 |

| individual sports | 51 | 38.3 |

| Sporting level | ||

| as a leisure activity | 41 | 30.8 |

| I also participate at a competitive level | 92 | 69.2 |

| Dimension | Variables | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic background | age, gender, parents’ education, parents’ labour market status, subjective financial situation, educational level | How old are you? What is your sex? What is the highest educational attainment of your mother/father? How could you evaluate your family’s financial status? Is your mother/father employed? What is the level of your current studies? |

| Sport-specific questions | sport frequency, sport type, sport level, career stages | How often do you pursue sport? What type of sport do you play most often? Which type of sport do you pursue? At what level do you pursue sport? When did you started to pursue a sport? What kind of stages could you determine in your sports biography? |

| Competitive activities | activities other than sport (e.g., study, work, other competitions | Besides sport, what kind of other activities could you mention in your life? How can you evaluate your school life and academic achievement? Have you ever been employed/are you employed? Do you pursue any other activities at a high level (e.g., playing a musical instrument)? |

| Individual motivation | personal drives | Why do you pursue sport? Why are you persistent in pursuing sport? Why do you persist with your sporting activities? |

| Sport persistence—microsystem | family peers coach | If you consider only your family (excluding other factors), why do you continue to do sports? If you consider only your peers (excluding other factors), why do you continue to do sports? If you consider only your coach (excluding other factors), why do you continue to do sports? |

| Sport persistence—mesosystem | family–school relationship family–sports–peers relationship | How does the relationship between your family and your school contribute to your perseverance in sport? How does the relationship between your family and your sporting teammates contribute to your perseverance in sport? |

| Sport persistence—exosystem | sporting environment | If you only consider your sporting environment, e.g., infrastructure (excluding other factors), why do you continue to do sports |

| Sport persistence—macrosystem | national culture and traditions | If you only consider national culture and traditions (excluding other factors), why do you continue to do sports? |

| Main Categories | Sub-Categories | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| disadvantage compensation | highlighting and supporting talent (n = 1) | “It was my foster parents who saved me, they were the ones who saw the talent in me.” (Participant No. 54) |

| detachment from the family (n = 1) | “Since I live at home, we are together a lot. I can get away from home in the meantime.” (Participant No. 119) | |

| introjected motivation | expectation (n = 2) | “to make them proud of me” (Participant No. 44) |

| “to make my parents proud of me” (Participant No. 45) | ||

| desire to prove (n = 14) | “because no one in my family plays sport at the level I do and it’s nice, when they watch me, cheered on me and are proud of me.” (Participant No. 40) | |

| “I would like to make them proud of me” (Participant No. 118) | ||

| “they are happy when they see a performance and it’s good to see them happy and proud.” (Participant No. 123) | ||

| person-related support | family-related motivation, sporting history (n = 15) | “because several members of my family played the sport” (Participant No. 39) |

| “I come from a sporty family, sport has been part of my everyday life since childhood” (Participant No. 52) | ||

| “Almost everyone on my dad’s side is involved in sport, so it was really through his influence that I started and have continued ever since.” | ||

| (Participant No. 142) | ||

| motivating a family member (n = 15) | “my mother teaches physical education, she motivates me” (Participant No. 12) | |

| “to encourage them to stay healthy and to have hobbies we can do together.” (Participant No. 81) | ||

| “because I can motivate them that no matter how bad my physical condition is (due to injuries), I won’t give up.” (Participant No. 115] | ||

| support for the future | future family motivation (n = 1) | “because I also want my children to play sport in the future.” (Participant No. 120) |

| “because I love it and I want my family to play sport when I have children” (Participant No. 133) | ||

| future livelihood (n = 3) | “I want to make a living from it later” (Participant No. 23) | |

| “I will even be able to spend the money on my family” (Participant No. 27) | ||

| “so that I can provide them with opportunities later on.” (Participant No. 46) | ||

| personal development (n = 6) | “they are very supportive, they do their best to help me achieve my goals and improve” (Participant No. 48) | |

| “get as much out of life as possible as a professional athlete” (Participant No. 109) | ||

| “I think my parents are a perfect example of if you don’t get out and you’re not part of a good community or you’re not playing sports, you don’t have anything that makes you feel good and you’re just in this dark kind of monotonous life, so you’re working, you’re in a job you don’t like, you’re in a school you don’t like, it can make you go crazy, so you get really sad then. So they motivate me to do everything I can while I’m young, to have friends, to go to the gym and everything, to not be like them so to speak.” (Participant No. 134) | ||

| outperformance (n = 1) | “because I want to reach a higher level in sport than them” (Participant No. 43) | |

| support related to family values | health promotion (n = 2) | “to avoid diseases from which my relatives have suffered and are suffering” (Participant No. 63) |

| “because my family is a bit overweight and I know how difficult it is to live like that” (Participant No. 86) | ||

| “healthy living, living as long as possible with loved ones in good health” (Participant No. 124) | ||

| shared values (n = 8) | “because sport is important to my family” (Participant No. 106) | |

| “they also think regular exercise is important” (Participant No. 111) | ||

| “I was brought up from an early age never to give up” (Participant No. 130) | ||

| joint activity (n = 3) | “they contribute well. And so we can talk, spend time together.” (Participant No. 4) | |

| “it could be a joint programme” (Participant No. 9) | ||

| “they know I like doing it, they always ask me about my progress or where I am at” (Participant No. 49) | ||

| source of pleasure (n = 14) | “I want to see them proud” (Participant No. 28) | |

| “my family supports me in this, and it is a source of joy for them to see me happy and getting on in life and doing what I want to do. And that motivates me.” (Participant No. 137) | ||

| relaxation (n = 1) | “tension relief” (Participant No. 26) | |

| “because it helps me unwind” (Participant No. 84) | ||

| “because this is what helps me relax and gives me happiness” (Participant No. 136) | ||

| love of sport (n = 3) | “I love it and it is part of my life” (Participant No. 34) | |

| “I have a relative and we know very well that he loves riding and he gives me a motivation because you can see that he really enjoys it and takes care of horses as well.” (Participant No. 135) |

| Main Categories | Sub-Categories | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| community motivation | collective conscientiousness (n = 5) | “For the sake of team unity, cultivating and maintaining friendships.” (Participant No. 38) “It’s because we are a team and if one person leaves, the team is no longer complete.” (Participant No. 43) “There were many times when I did it just for them, so as not to let them down” (Participant No. 132) |

| altruism (n = 7) | “Because I’m not going to leave them in the middle of a tournament.” (Participant No. 29) “Because I know that they need me and they count on me in the team and because I like to play sports with them.” (Participant No. 40) “We’ve built a good team over the years and it would be a shame to leave that environment. I don’t want to let them down.” (Participant No. 123) | |

| joint activity (n = 8) | “A common point for conversation, a good and meaningful time with friends.” (Participant No. 27) | |

| “Because together these times are good times.” (Participant No. 35) | ||

| “They motivate me and they play the same sport and I enjoy my time with them.” (Participant No. 48) | ||

| motivating peers (n = 2) | “I want to motivate them myself.” (Participant No. 69) “I motivate them to achieve better results. ” (Participant No. 70) “Because I can encourage them to take up sport themselves.” (Participant No. 87) | |

| peer comparison (n = 7) | “Because I want to be better than them, and I like being envied.” (Participant No. 75) “To be accepted by them.” (Participant No. 78) “It’s uplifting to be able to do better among people who spend most of their free time just staying at home, hanging out, partying. With less free time, it’s hard to reach a level you’re happy with. And if I take my fellow teammates into acccount, I am happy if I can show them one or two things by example or if I can get their attention and recognition by my will, attention and performance.” (Participant No. 116) | |

| peer support (n = 40) | “It’s about sticking together and fighting for each other.” (Participant No. 52) “I like my teammates, there’s always a good atmosphere.” (Participant No. 60) “Because I play sport with my friends and they support me to keep going.” (Participant No. 86) “My circle of friends and my friends are here on the farm, the people I ride with and compete with, and they always support each other, we talk about everything, and they’re important to us, so they always add to the atmosphere, so that’s why.” (Participant No. 137) | |

| sense of belonging (n = 5) | “I see my team as a second family.” (Participant No. 33) “I really like my team, and most of my friends are athletes anyway.” (Participant No. 83) “It’s a good community, I like it here, and I have many friends I’ve met through horse riding here.” (Participant No. 139) | |

| positive environment (n = 7) | “I am in a supportive environment with people who are persistent.” (Participant No. 16) “The environment and atmosphere is motivating.” (Participant No. 102) “ They motivate me, encourage me, praise me all the time, everyone is positive towards me and the circumstances are positive.” (Participant No. 131) | |

| individual motivation | desire to prove (n = 3) | “To show that I am somebody.” (Participant No. 31) “I want to prove myself to them.” (Participant No. 103) |

| individual development (n = 11) | “It’s uplifting to be able to do better among people who spend most of their free time just hanging out, hanging out, partying.” (Participant No. 19) “With less free time, it’s difficult to reach a level you’re happy with. And if I consider my fellow coaches, I am happy if I can show them one or two things by example or if I can get their attention and recognition by my will, attention and performance.” (Participant No. 116) “I’m doing my best, but we play as a team.” (Participant No. 54) “To get as much out of life as possible as an athlete.” (Participant No. 109) | |

| health promotion (n = 2) | “For my health” (Participant No. 76) “To get fit, that’s what they motivates me to achieve” (Participant No. 80) | |

| recognition (n = 5) | “I like it when others praise my performance.” (Participant No. 11) | |

| “I like to be with my teammates and I like to be praised for being a good goalkeeper.” (Participant No. 25) | ||

| “To be seen for who I am and to be respected and recognised. I want them to be proud of me.” (Participant No. 68) | ||

| relational motivation | networking (n = 5) | “It builds team spirit and community.” (Participant No. 84) “Because I have a lot of friends from there, so that’s when I meet them. These relationships are important in my life.” (Participant No. 119) “Through sport you can meet a lot of people, make a lot of friends. And some people are motivated by it, some people are not, but I am.” (Participant No. 143) |

| being a role model (n = 2) | “…because they might take me as an example.” (Participant No. 5) “I want to set an example to them and they motivate me.” (Participant No. 55) “Because I can set an example for them by having a willingness to train that others would like to have.” (Participant No. 115) |

| Main Categories | Sub-Categories | Examples |

|---|---|---|

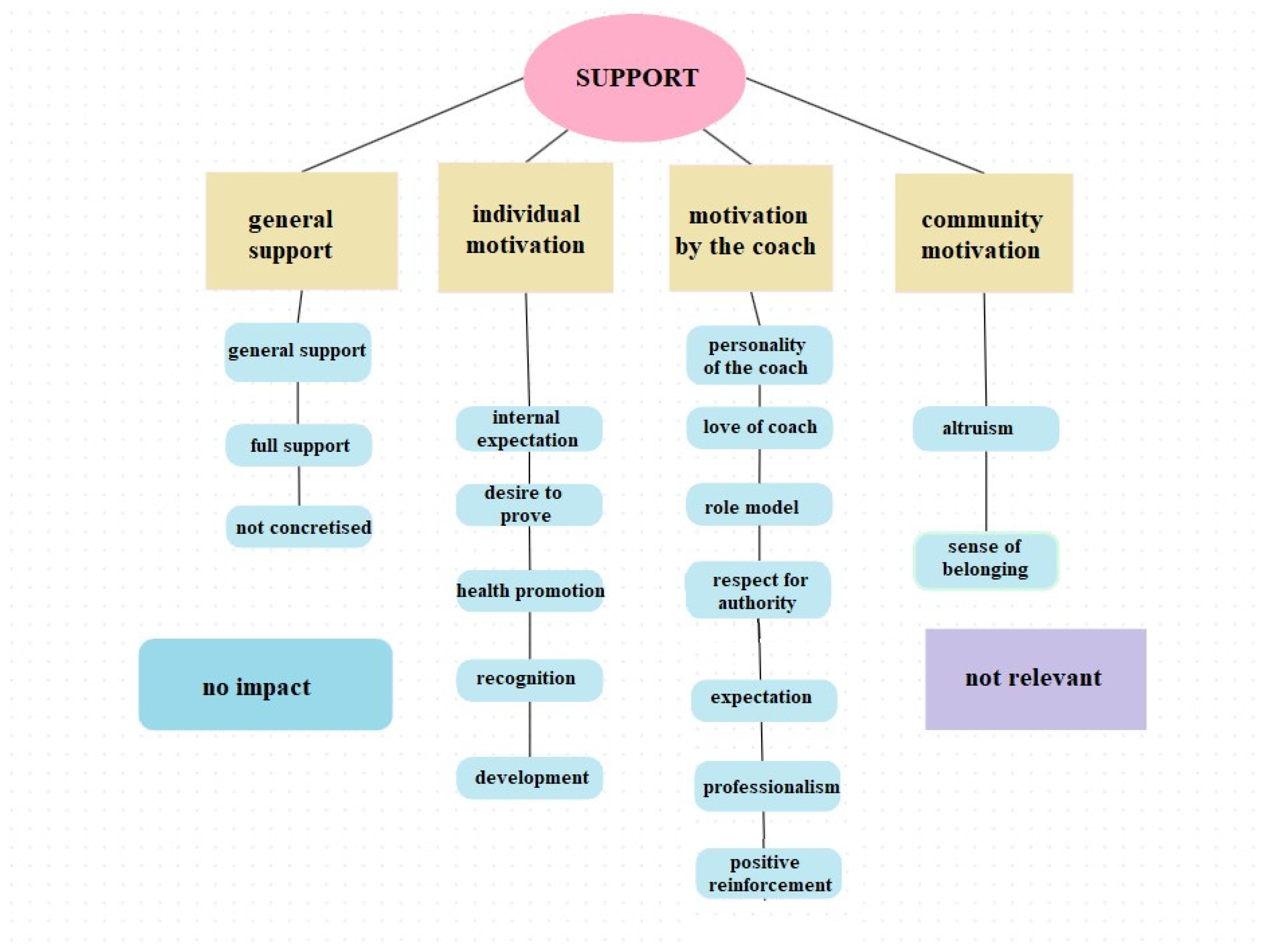

| community motivation | altruism (n = 3) | “Because I would not disappoint them and help them.” (Participant No. 99) “It helps to keep the group together” (Participant No. 126) “Well, because I’ve developed such a relationship with the coach that whatever happens, I wouldn’t let the team down, I wouldn’t let the coach down.” (Participant No. 140) |

| sense of belonging (n = 5) | “To contribute to the team.” (Participant No. 27) “He is looking after the interests of the team.” (Participant No. 127) | |

| individual motivation | internal expectation (n = 3) | “Because I want to see that talent in myself” (Participant No. 45) “To make you them proud of me” (Participant No. 78) |

| desire to prove (n = 7) | “I want to prove that I can indeed do anything.” (Participant No. 28) “To show that I am persistent” (Participant No. 82) “I want to show my old coaches how much I’ve improved, and I don’t want to let my current ones down.” (Participant No. 113) | |

| health promotion (n = 4) | “…because it does a lot to keep me healthy.” (Participant No. 5) “…supports me in living a healthy lifestyle.” (Participant No. 69) | |

| recognition (n = 2) | “I want them to be proud of me.” (Participant No. 118) “To get his attention.” (Participant No. 119) | |

| development (n = 19) | “He motivates me, prepares me well, and has the knowledge and experience for the sport.” (Participant No. 48) “It not only teaches me to be a better player but also helps me to become a better person.” (Participant No. 52) | |

| motivation by the coach | personality of the coach (n = 7) | “We have a good coach, sometimes strict, as it should be.” (Participant No. 60) “My coach saw my potential; he thinks I can have a future in this sport and supports me.” (Participant No. 114) “…I’ve been riding in several places, so I’ve observed several trainers and how they teach, treat the horses, and relate to people. And my trainer was a very, very pleasant positive disappointment because I thought all trainers were a little bit like that, a little bit more temperamental, or well, they don’t really care about the kids’ feelings, and they really just focus on the sport, but she’s totally not like that.” (Participant No. 134) |

| love of coach (n = 5) | “Because he is the best coach.” (Participant No. 18) “I really like our coach” (Participant No. 91) “Best coach in the world!” (Participant No. 104) | |

| role model (n = 3) | “He does it at a very high professional level; he’s a role model.” (Participant No. 105) “Well, actually, there’s probably one coach at the moment that I look up to and who influences me, well he’s the one that I look up to, and precisely because of the way that I look up to him, the training sessions that he has and it’s definitely worth going to. And it’s not that you want to be like him, but it’s just that you’re probably not stupid if that’s where he’s positioned himself.” (Participant No. 141) | |

| respect for authority (n = 4) | “I respect and appreciate his authority as a competent person in his profession, and that’s really all.” (Participant No. 142) “I respect him too; I look up to my coach.” (Participant No. 143) | |

| positive reinforcement (n = 7) | “I like it when he praises me.” (Participant No. 25) “He always only encourages me” (Participant No. 83) “Because it gives a lot of strength and encouragement.” (Participant No. 88) “He counts on me, he is proud of me, he motivates me.” (Participant No. 131) | |

| expectation (n = 6) | “No matter how strict the coach is, you must stick it out because he’s not coaching for nothing.” (Participant No. 4) “I have worked with several coaches in my sporting career, and I would like to thank them for their work by saying that I do my job to the best of my ability” (Participant No. 128) “Because the coach also has a lot of work to do. And then I know that I have to do the same, and then all the work that I put in, that we put in together, doesn’t go to waste.” (Participant No. 132) | |

| professionalism (n = 6) | “They have very good professional skills.” (Participant No. 34) “He’s very consistent and has good training sessions.” (Participant No. 39) “Because the coach can design the right training plan for me.” (Participant No. 87) “For the transfer of professional knowledge.” (Participant No. 108) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Selejó Joó, B.T.; Czipa, H.; Bódi, R.; Lupócz, Z.; Paronai, R.; Tóth, B.T.; Tóth, H.L.; Kocsner, O.C.; Lovas, B.; Lukácsi, C.; et al. Qualitative Analysis of Micro-System-Level Factors Determining Sport Persistence. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk9040196

Selejó Joó BT, Czipa H, Bódi R, Lupócz Z, Paronai R, Tóth BT, Tóth HL, Kocsner OC, Lovas B, Lukácsi C, et al. Qualitative Analysis of Micro-System-Level Factors Determining Sport Persistence. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2024; 9(4):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk9040196

Chicago/Turabian StyleSelejó Joó, Bence Tamás, Hanna Czipa, Regina Bódi, Zsuzsa Lupócz, Rozália Paronai, Benedek Tibor Tóth, Hanna Léna Tóth, Oszkár Csaba Kocsner, Buda Lovas, Csanád Lukácsi, and et al. 2024. "Qualitative Analysis of Micro-System-Level Factors Determining Sport Persistence" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 9, no. 4: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk9040196

APA StyleSelejó Joó, B. T., Czipa, H., Bódi, R., Lupócz, Z., Paronai, R., Tóth, B. T., Tóth, H. L., Kocsner, O. C., Lovas, B., Lukácsi, C., Kovács, M., & Kovács, K. E. (2024). Qualitative Analysis of Micro-System-Level Factors Determining Sport Persistence. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 9(4), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk9040196