Governing Distant-Water Fishing within the Blue Economy in Madagascar: Policy Frameworks, Challenges and Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

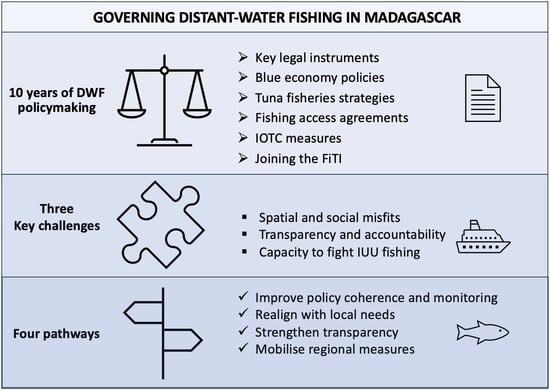

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of National and International Legal and Policy Frameworks Governing Distant-Water Fishing in Madagascar

3.1.1. The Fishery and Aquaculture Code (2015)

3.1.2. The Blue Policy Paper (2015)

3.1.3. The National Strategies for the Management of Tuna Fisheries (2014 and 2021)

3.1.4. Law Regarding Maritime Zones in the Maritime Space under the Jurisdiction of the Republic of Madagascar (2018)

3.1.5. Commitment to the Fisheries Transparency Initiative in 2021

3.1.6. The Malagasy Blue Economy Strategy for the Fishery and Aquaculture Sector (2022)

3.1.7. The UNCLOS as the International Instrument Framing Access by Distant-Water Fishing Nations (1982)

3.2. Governance Challenges Linked to Distant-Water Fishing in the Malagasy Waters

3.2.1. Spatial and Social Misfits of DWF Policies

3.2.2. Pertaining Issues of Transparency and Accountability

3.2.3. A Still Limited Capacity to Fight IUU Fishing

4. Discussion on Pathways towards an Improved DWF Policy Framework

4.1. Address Policy Coherence and Improve Monitoring

4.2. Realign National Policy and Actions with Local Needs

4.3. Further Strengthen Transparency in DWF

4.4. Mobilise Measures Adopted at the Regional Indian Ocean Level

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breuil, C.; Grima, D. Baseline Report Madagascar; IOC: Ebene, Mauritius, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- MRHP. Blue Policy Letter—Lettre de Politique Bleue: Pour une Économie Bleue, Valorisant le Travail des Pêcheurs et Aquaculteurs, Durabilisant la Création de Ses Richesses, et Prenant en Compte le Bien Être Écologique des Ressources Halieutiques; Ministère des Ressources Halieutiques et de la Pêche: Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2015; Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/fr/c/LEX-FAOC163970/#:~:text=Madagascar%20(Niveau%20national)-,Lettre%20de%20Politique%20Bleue.,principales%20orientations%20jusqu’en%202025 (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- INSTAT. Enquête périodique auprès des ménages. In Résultats Globaux du Recensement Général de la Population et de L’habitation de 2018 de Madagascar; INSTAT: Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MRHP. Enquete Cadre Nationale 2011–2012; MRHP: Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- MAEP ‘Ministère de l’Agriculture, de l’Elevage et de la Pêche’ (Ministry in charge of fisheries in 2021). Update of the National Strategy for the Management of Tuna Fisheries. 2021. Available at the tuna fisheries unit and the WWF. Collected via email exchanges with the consultant who wrote the strategy.

- Rakotosoa, R. Impacts socioéconomiques de la Pêche thonière industrielle à Madagascar. In Proceedings of the Lancement de la Campagne Thonière 2017, Antsiranana, Madagascar, 24 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnier, A.F. La Pêche du Thon à Madagascar. In Bulletin de Madagascar; Haut Commissariat de la République Française à Madagascar et Dépendances, Service Général de L’information: Antananarivo, Madagascar, 1961; Volume 185, Available online: https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/pleins_textes_7/b_fdi_59-60/010026680.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- White, E.R.; Baker-Médard, M.; Vakhitova, V.; Farquhar, S.; Ramaharitra, T.T. Distant water industrial fishing in developing countries: A case study of Madagascar. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 216, 105925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USTA. Bulletin Statistique Thonier 2017 de l’Unité Statistique Thonière d’Antsiranana; USTA: Antsiranana, Madagascar, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IOTC. Catch History between 1950 and 2016 for Albacore, Bigeye Tuna, Skipjack Tuna, Yellowfin Tuna and Swordfish; IOTC: Victoria, Seychelles, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Campling, L. The EU-Centered Commodity Chain in Canned Tuna and Upgrading in Seychelles; Queen Mary University of London: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- SFA. Fisheries Statistical Report, Semester 1, Year 2016; SFA: Mahe, Seychelles, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, G.; Pittman, J.; Alexander, S.M.; Berdej, S.; Dyck, T.; Kreitmair, U.; Rathwell, K.J.; Villamayor-Tomas, S.; Vogt, J.; Armitage, D. Institutional fit and the sustainability of social–ecological systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggisberg, S.; Jaeckel, A.; Stephens, T. Transparency in fisheries governance: Achievements to date and challenges ahead. Mar. Policy 2022, 136, 104639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. US $142.8 Million Potentially Lost Each Year to Illicit fishing in the South West Indian Ocean. 2023. Available online: https://www.wwf.eu/?10270441/US1428-million-potentially-lost-each-year-to-illicit-fishing-in-the-South-West-Indian-Ocean (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- World Bank. Second South West Indian Ocean Fisheries Governance and Shared Growth Project—Region & Madagascar (P153370). 2017. Available online: https://www.swiofish2.mg/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Project-Appraisal-Document-PAD-P153370-1.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- IOTC. Madagascar 2020 National Report to the IOTC. 2020. Available online: https://www.iotc.org/documents/SC/23/NR11 (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Belhabib, D.; Sumaila, U.R.; Lam, V.W.Y.; Zeller, D.; Le Billon, P.; Kane, E.A.; Pauly, D. Euros vs. Yuan: Comparing European and Chinese Fishing Access in West Africa. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOTC. Madagascar Compliance Report| IOTC. IOTC-2023-CoC20-CR14, 2023. Available online: https://iotc.org/documents/madagascar-24 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Le Manach, F.; Andriamahefazafy, M.; Harper, S.; Harris, A.; Hosch, G.; Lange, G.-M.; Zeller, D.; Sumaila, U.R. Who gets what? Developing a more equitable framework for EU fishing agreements. Mar. Policy 2013, 38, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, E. Madagascar: Opaque foreign fisheries deals leave empty nets at home. Mongabay News, 9 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Andriamahefazafy, M.; Kull, C.A.; Campling, L. Connected by sea, disconnected by tuna? Challenges to regionalism in the Southwest Indian Ocean. J. Indian Ocean Reg. 2019, 15, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorez, B. Small Scale Fisheries at Risk: Madagascar Signs Destructive Fishing Agreements with Chinese Investors. Coalition for Fair Fisheries Arrangements. 17 November 2020. Available online: https://www.cffacape.org/publications-blog/small-scale-fisheries-at-risk-madagascar-signs-destructive-fishing-agreements-with-chinese-investors (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Gagern, A.; Bergh, J.v.D. A critical review of fishing agreements with tropical developing countries. Mar. Policy 2013, 38, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gegout, C. Unethical power Europe? Something fishy about EU trade and development policies. Third World Q. 2016, 37, 2192–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Manach, F.; Andriamahefazafy, M.; Legroux, N.; Quentin, L. Questionning Fishing Access Agreements towards Social and Ecological Health in the Global South. AFD, Research Paper 203. 2021. Available online: https://www.afd.fr/en/ressources/questionning-fishing-access-agreements-towards-social-and-ecological-health-global-south (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Nash, K.L.; MacNeil, M.A.; Blanchard, J.L.; Cohen, P.J.; Farmery, A.K.; Graham, N.A.J.; Thorne-Lyman, A.L.; Watson, R.A.; Hicks, C.C. Trade and foreign fishing mediate global marine nutrient supply. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2120817119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing, A. Are The EU’s Fisheries Agreements Helping to Develop African Fisheries? CFFA-CAPE: Etterbeek, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- IOTC. Conservation and Management Measures (CMMs) | IOTC. 2023. Available online: https://iotc.org/cmms (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- IOTC. On the Management of Drifting FADs -DFADS (Kenya et al.) | IOTC. IOTC-2022-S26-REF02. 2022. Available online: https://iotc.org/documents/management-drifting-fads-dfads-kenya-et-al (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- IOTC. Objection from Madagascar to IOTC Resolution 21/01 | IOTC. Circular IOTC CIRCULAR 2021-50. 2021. Available online: https://www.iotc.org/documents/objection-madagascar-iotc-resolution-2101 (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Razafindrakoto, M.; Roubaud, F.; Wachsberger, J.-M. L’énigme et le Paradoxe—Économie Politique de Madagascar; Collection Synthèses; Marseilles; IRD Éditions: Marseilles, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M. Diagnosing Institutional Fit: A Formal Perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddick, D. The dimensions of a transnational crime problem: The case of iuu fishing. Trends Organ. Crime 2014, 17, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, F.L.; Preiss-Bloom, S.; Dayan, T. Recent Evidence of Scale Matches and Mismatches Between Ecological Systems and Management Actions. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep. 2022, 7, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamahefazafy, M. The Politics of Sustaining Tuna, Fisheries and Livelihoods in the Western Indian Ocean. A Marine Political Ecology Perspective, Université de Lausanne, Faculté des Géosciences et de L’environnement. 2020. Available online: https://serval.unil.ch/notice/serval:BIB_7E0D668DF275 (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Davis, R.A.; Hanich, Q. Transparency in fisheries conservation and management measures. Mar. Policy 2022, 136, 104088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G.W.; Keen, M.; Hanich, Q. Can Greater Transparency improve the Sustainability of Pacific Fisheries? Mar. Policy 2022, 136, 104251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orange Actu. Accord de Pêche: Reprise des Négociations Avec l’Union Européenne. Orange actu Madagascar. 5 July 2022. Available online: https://actu.orange.mg/accord-de-peche-reprise-des-negociations-avec-lunion-europeenne/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Kroodsma, D.A.; Hochberg, T.; Davis, P.B.; Paolo, F.S.; Joo, R.; Wong, B.A. Revealing the global longline fleet with satellite radar. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IOTC. Madagascar—National Report 2019. National Report IOTC-2019-SC22-NR14. 2019. Available online: https://iotc.org/fr/documents/SC/22/NR14 (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- SADC. Protecting Our Fisheries—Working Towards a Common Future. 2021. Available online: https://stopillegalfishing.com/publications/protecting-our-fisheries-working-towards-a-common-future/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Lindström, L.; De La Torre-Castro, M. Tuna or Tasi? Fishing for Policy Coherence in Zanzibar’s Small-Scale Fisheries Sector. In The Small-Scale Fisheries Guidelines; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasiak, R.; Wabnitz, C.C.; Daw, T.; Berger, M.; Blandon, A.; Carneiro, G.; Crona, B.; Davidson, M.F.; Guggisberg, S.; Hills, J.; et al. Towards greater transparency and coherence in funding for sustainable marine fisheries and healthy oceans. Mar. Policy 2019, 107, 103508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waeber, P.O.; Wilmé, L.; Mercier, J.-R.; Camara, C.; Ii, P.P.L. How Effective Have Thirty Years of Internationally Driven Conservation and Development Efforts Been in Madagascar? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, J.; Cheek, J.Z.; Andriamaro, L.; Bakoliarimisa, T.M.; Galitsky, C.; Rabearivololona, O.; Rakotobe, D.J.; Ralison, H.O.; Randriamiharisoa, L.O.; Rasamoelinarivo, J.; et al. Insights from practitioners in Madagascar to inform more effective international conservation funding. Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2022, 17, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scales, I. The future of conservation and development in Madagascar: Time for a new paradigm? Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2014, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerry, C.R.; Exeter, O.M.; Witt, M.J. Monitoring global fishing activity in proximity to seamounts using automatic identification systems. Fish Fish. 2022, 23, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattebert, C. La Pêche Traditionnelle ou Petite Pêche Maritime à Madagascar: Un État des Lieux. CAPE-CFFA. 2020. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d402069d36563000151fa5b/t/5e996c4303457a60bf3b3a72/1587113109461/200415+Report+Madagascar.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Rocliffe, S.; Harris, A. Scaling success in octopus fisheries management in the Western Indian Ocean. In Proceedings of the Workshop, Stone Town, Zanzibar, 3–5 December 2014; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- CAPE-CFFA. 10 priorities for the future of Sustainable Fisheries Partnership Agreements. CAPE-CFFS. 2020. Available online: https://www.cffacape.org/publications-blog/ten-priorities-for-the-future-of-sustainable-fisheries-partnership-agreements (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Pittman, J.; Wabnitz, C.C.; Blasiak, R. A global assessment of structural change in development funding for fisheries. Mar. Policy 2019, 109, 103644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.; Ardron, J.; Gjerde, K.; Currie, D.; Rochette, J. Advancing marine biodiversity protection through regional fisheries management: A review of bottom fisheries closures in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Mar. Policy 2015, 61, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinan, H.; Bailey, M.; Hanich, Q.; Azmi, K. Common but differentiated rights and responsibilities in tuna fisheries management. Fish Fish. 2022, 23, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of the Legal Document | Adoption Year | Area Covered by the Text |

|---|---|---|

| National strategy on the management of tuna fisheries in Madagascar 1 | 2014 | Main priorities for the management of DWF and improvement of governance |

| Law n° 2015-053 of December 2nd 2015 regarding the Fishery and Aquaculture Code 2 | 2015 | Modalities of DWF |

| Blue Policy paper 3 | 2015 | Main vision and aspirations for DWF in Madagascar |

| Law n° 2018-025 regarding maritime zones in the maritime space under the jurisdiction of the Republic of Madagascar 1 | 2018 | Contextualising fishing activities in the exclusive economic zone of Madagascar |

| Updated national strategy on the management of tuna fisheries in Madagascar 1 | 2021 | Updated priorities and actions for the management of DWF |

| Fisheries Transparency Initiative Standards 4 | 2021 | Standards regarding transparency of DWF agreements and modalities of operation |

| Malagasy blue economy strategy for the fishery and aquaculture sector | 2022 | Improvement of fishing access agreements and the fight against IUU fishing. |

| Content | Ref. in the Law | Comments on Implementation (as of September 2022) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modalities of fishing |

| Art. 26 |

|

| Art. 28 and 31 | ||

| Art. 30 | ||

| Art. 34.b | ||

| Art. 35.c | ||

| Content of access agreements |

| Art. 35.a | The elements prescribed in Art. 35b are present in the existing template of fishing access agreements used by the ministry. These elements are also present in all EU public agreements. Agreements that allowed for a consultation also included a clause mentioning that agreements might not be renewed in the case of a lack of respect of the agreements’ terms or lack of respect of fishing modalities as presented above. |

Mandatory key contents of agreements:

| Art. 35.b | ||

| Art. 36 | Implemented through the adoption of the Southwest Indian Ocean Fisheries Commission (SWIOFC) guideline for minimum terms and conditions on fishing access agreements in 2018 | |

| Fishing licenses | Content of licenses:

| Art. 38 |

|

Conditions under which licenses will not be renewed:

| Art. 40 | White et al. [8] reported that there is some illegal fishing within marine protected areas and territorial waters while authorities interviewed mentioned such occurrences have been limited over the years. WWF [15] also indicated that more than 2500 metric tonnes of tuna catch might be under-reported in Madagascar. If these fishing operators are identified, it could impact the renewal of their fishing licenses. |

| Key Elements of the Strategy | Indicators of Success | Year of Activity Launch | Achievement as of September 2022 | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activities in the 2021 strategy | ||||

| R.1.2. Establish and operationalise a fishery consultation platform to align with the reform to improve fishery management in Madagascar |

| 2021 | Ongoing 1 |

|

| R.2.1. Strengthening statistical and information systems |

| 2022 | Partially implemented |

|

| R.1.3. Systematic publication of licences, royalties and bilateral agreements |

| 2022 | Partially implemented |

|

| R.1.4. Reviewing the way fees are calculated |

| 2021 | Implemented |

|

| R.5.1. Promote the implementation of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) decree on fishing activities (fishing agreement) |

| - | Not implemented |

|

| Activities in 2014 tuna strategy also present in 2021 strategy | ||||

| R.1.5. Improvement of agreements on fisheries by harmonizing these agreements at the national level |

| 2019 | Ongoing |

|

| R.1.3. Establishing a chart of dissuasive sanctions; classifying sanctions by fishery and type of offence |

| - | Not implemented |

|

| 2014 | Ongoing | ||

| R.3.3. Strengthening MCS systems in Madagascar and in the region: VMS data, port inspections, offshore control, observer program, information exchange in the region |

| 2014 | Ongoing |

|

| R.3.1. Increasing landings, trans-shipments and stopovers of DWF fleets in Malagasy ports by consulting operators and service providers |

| - | Not implemented |

|

| Party of the Agreement | Flag State | Type | Type of Vessel | Nbr of Vessels | Status (as of September 2022) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Union | Spain and France | Public | Purse seiners | 32 | Signed 1 | 4-year agreement |

| Longliners | 33 | |||||

| Interatun | Seychelles/Mauritius | Private | Purse seiners | 5 | Signed | 2-year agreement |

| Japan Tuna | Japan | Private | Longliners | 10 | Signed | 2-year agreement |

| Dae Young Fisheries | South Korea/ Taiwan | Private | Purse seiners | 3 | Applied for renewal | |

| Private | Longliners | 72 | Applied for renewal | |||

| ANABAC | Seychelles/Mauritius | Private | Purse seiners | 6 | Applied for renewal | |

| OPAGAC | Seychelles/Mauritius | Private | Purse seiners | 6 | Applied for renewal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andriamahefazafy, M. Governing Distant-Water Fishing within the Blue Economy in Madagascar: Policy Frameworks, Challenges and Pathways. Fishes 2023, 8, 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8070361

Andriamahefazafy M. Governing Distant-Water Fishing within the Blue Economy in Madagascar: Policy Frameworks, Challenges and Pathways. Fishes. 2023; 8(7):361. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8070361

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndriamahefazafy, Mialy. 2023. "Governing Distant-Water Fishing within the Blue Economy in Madagascar: Policy Frameworks, Challenges and Pathways" Fishes 8, no. 7: 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8070361

APA StyleAndriamahefazafy, M. (2023). Governing Distant-Water Fishing within the Blue Economy in Madagascar: Policy Frameworks, Challenges and Pathways. Fishes, 8(7), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8070361