Physiological Responses of Kalibaus (Labeo calbasu) to Temperature Changes: Metabolic, Haemato-Biochemical, Hormonal and Immune Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Experimental Site

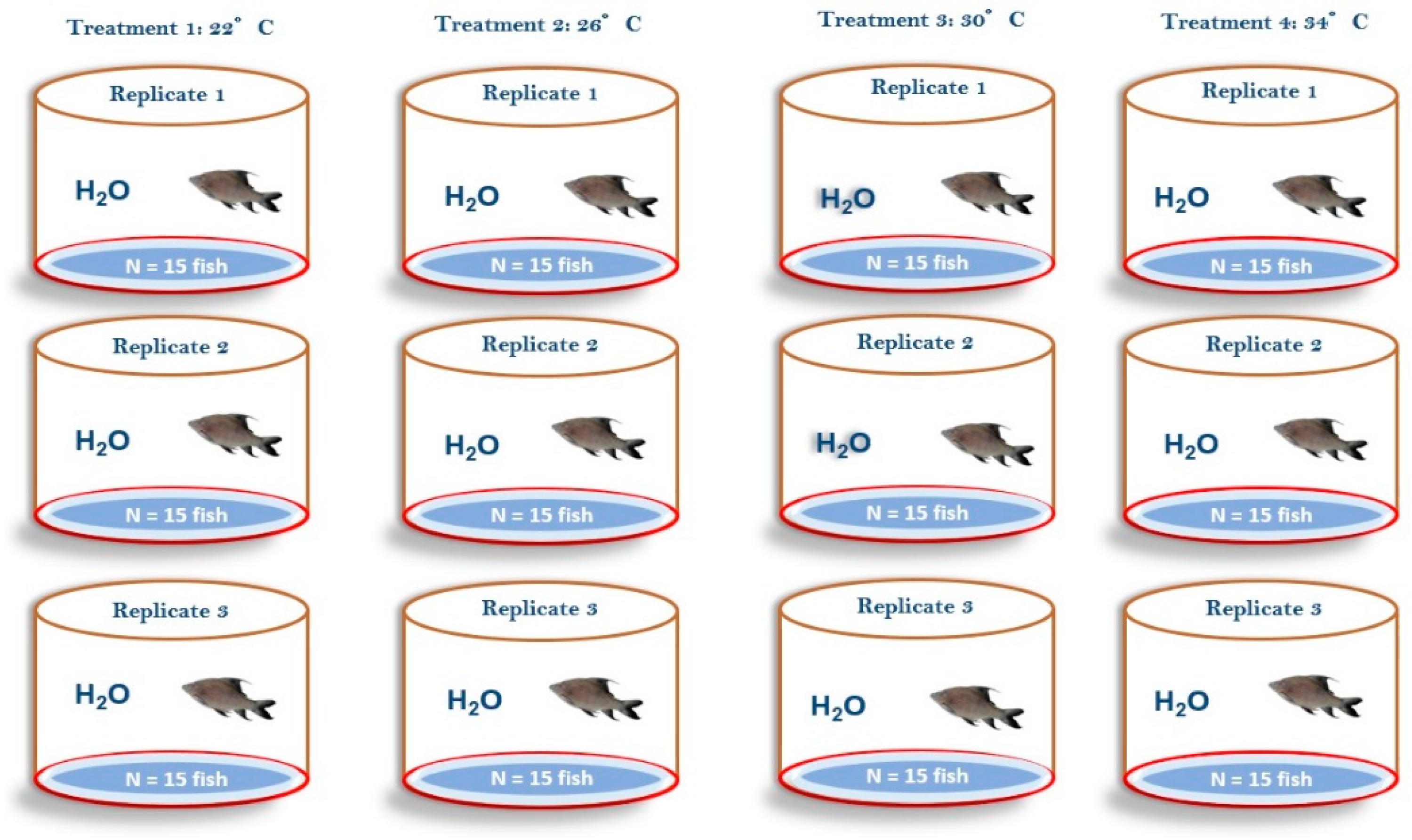

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Water Quality Measurements

2.4. Growth and Metabolic Rate Study

2.5. Haematological Indices Study

2.6. Serum Biochemical Parameters Study

2.7. Hormonal Concentration Study

2.8. Immune Responses Study

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Water Quality Measurements

3.2. Effect of Temperature on Growth and Metabolism

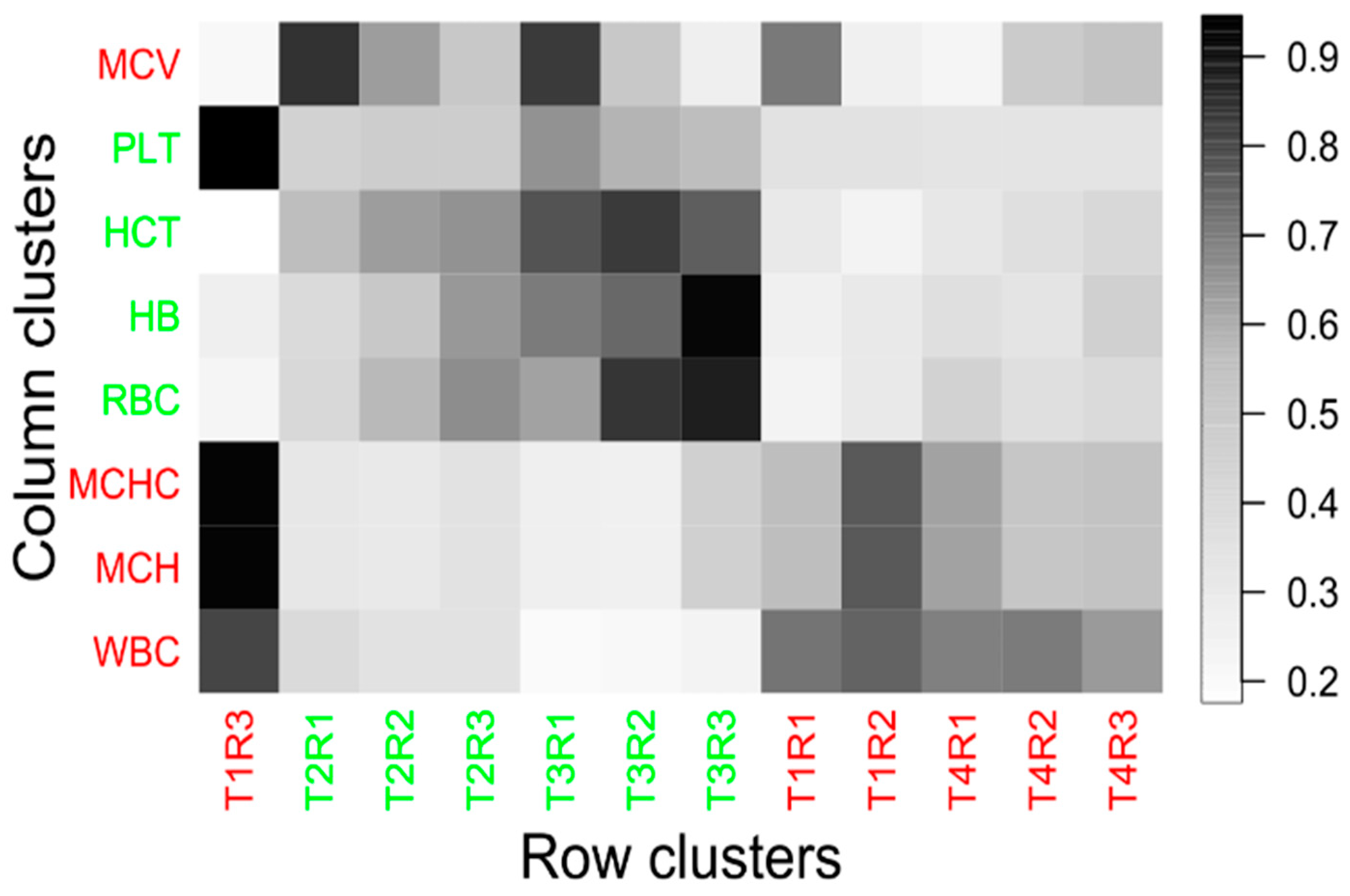

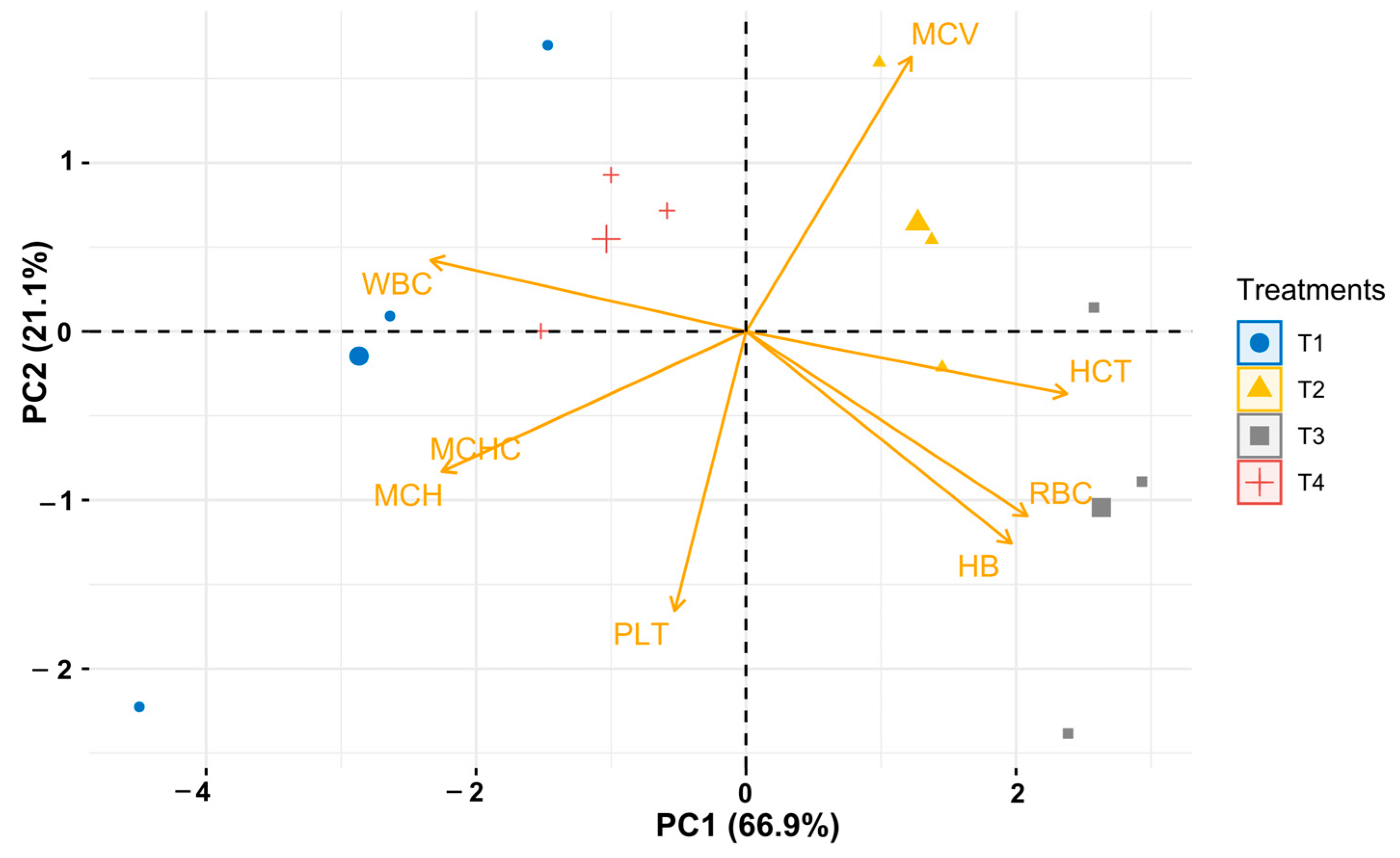

3.3. Effect of Temperature on Haematological Parameters

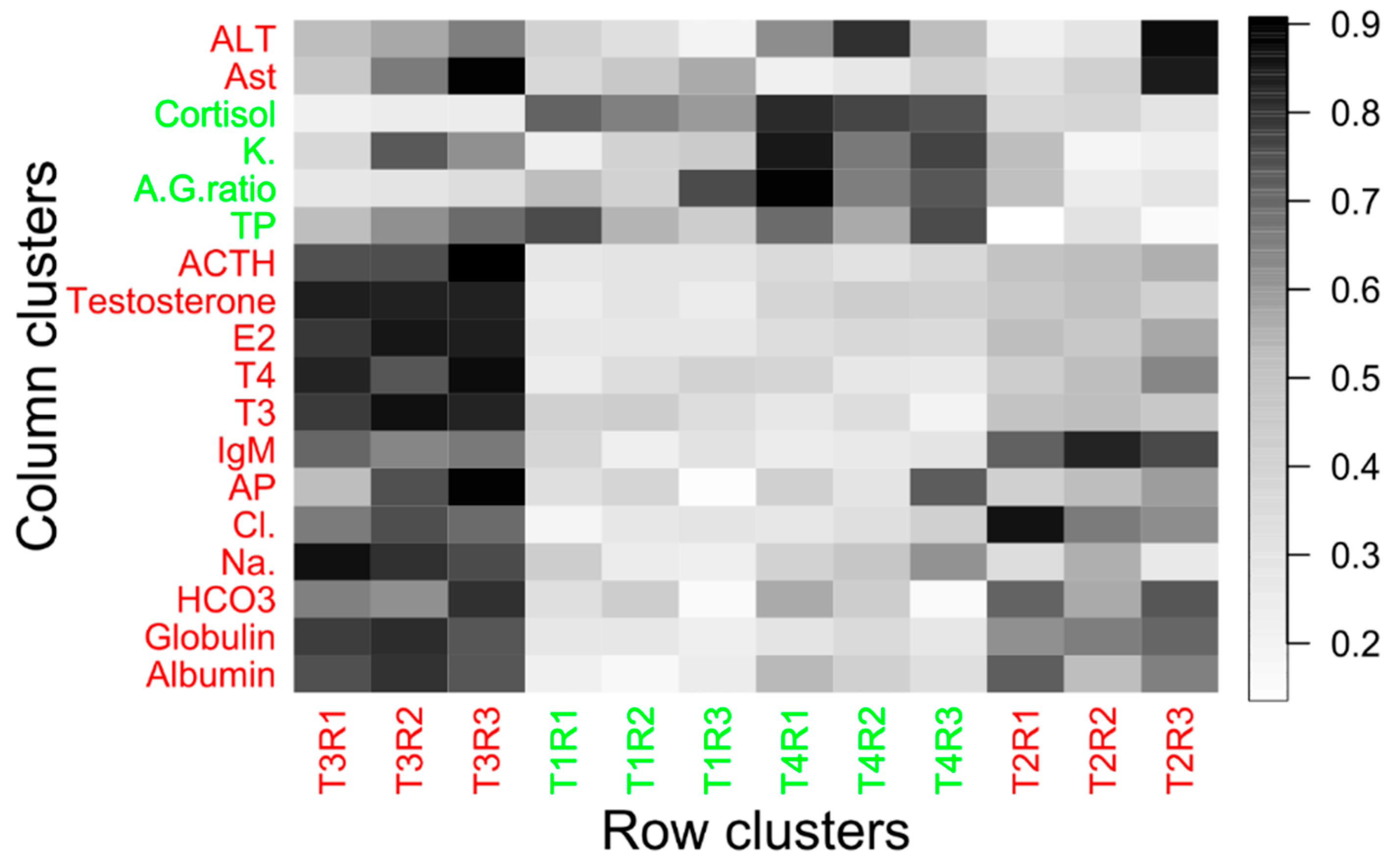

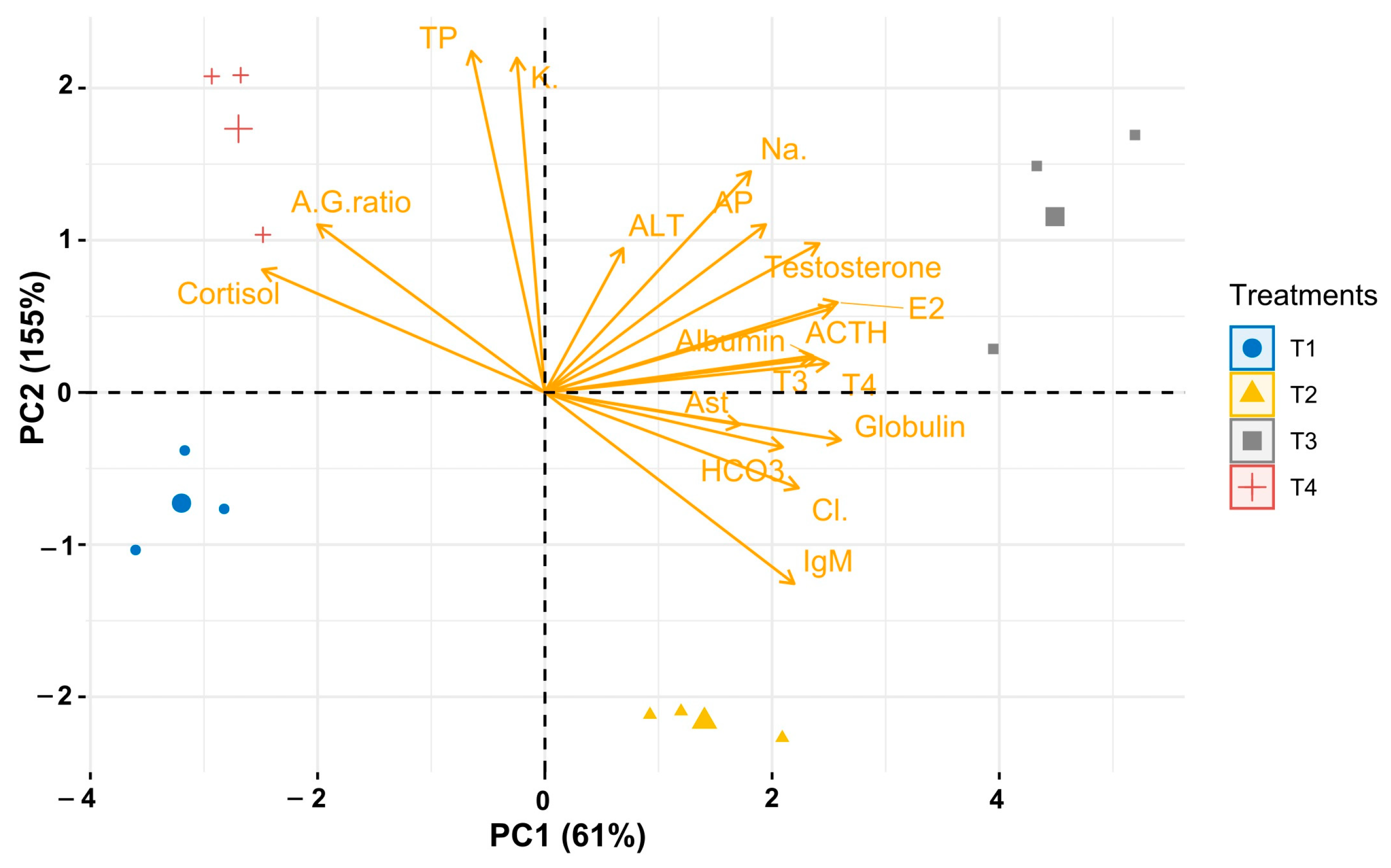

3.4. Effect of Temperature on Biochemical Responses

3.5. Effect of Temperature on Hormonal Activity

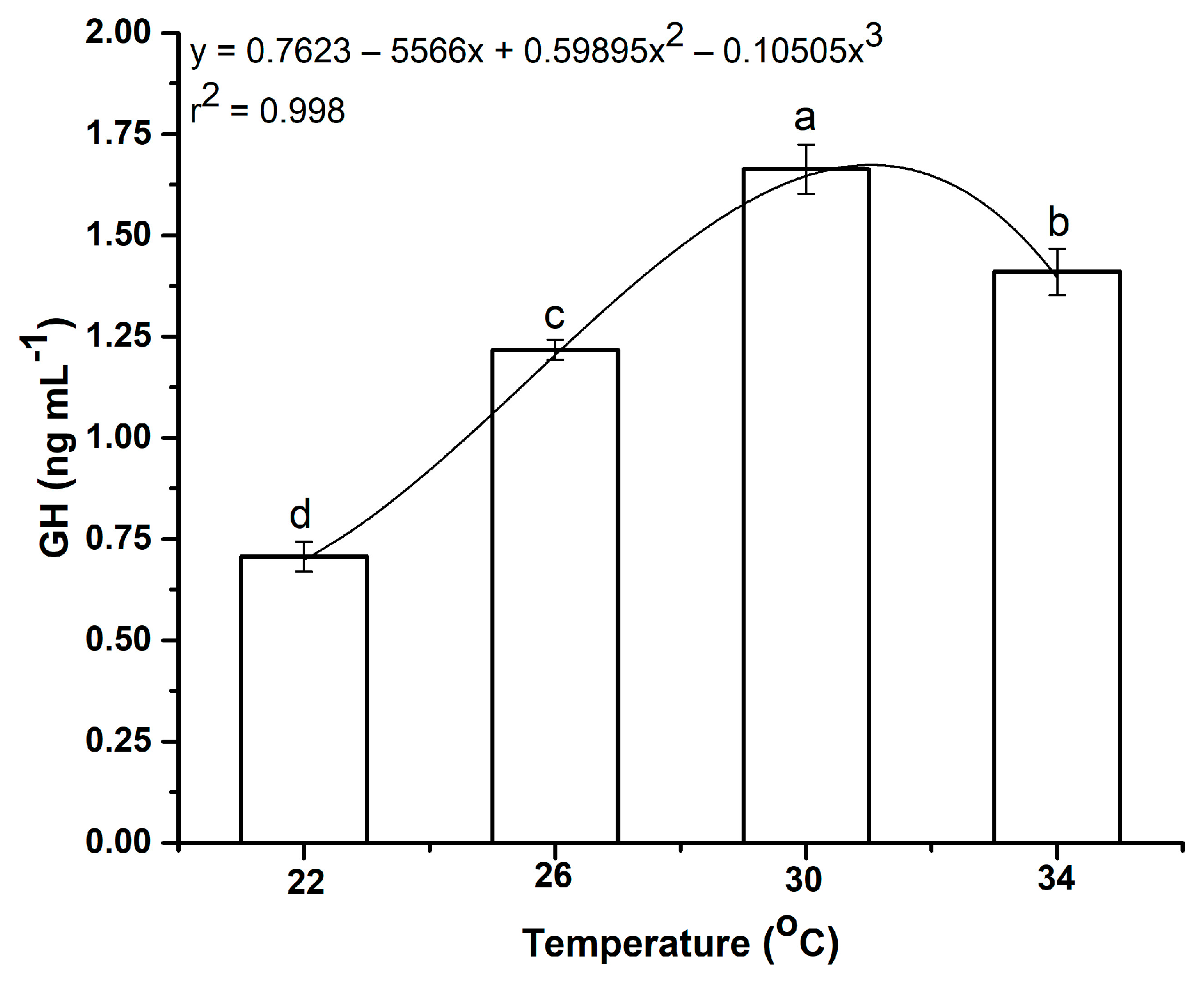

3.5.1. Impacts of Water Temperature Fluctuations on Growth Hormone Levels

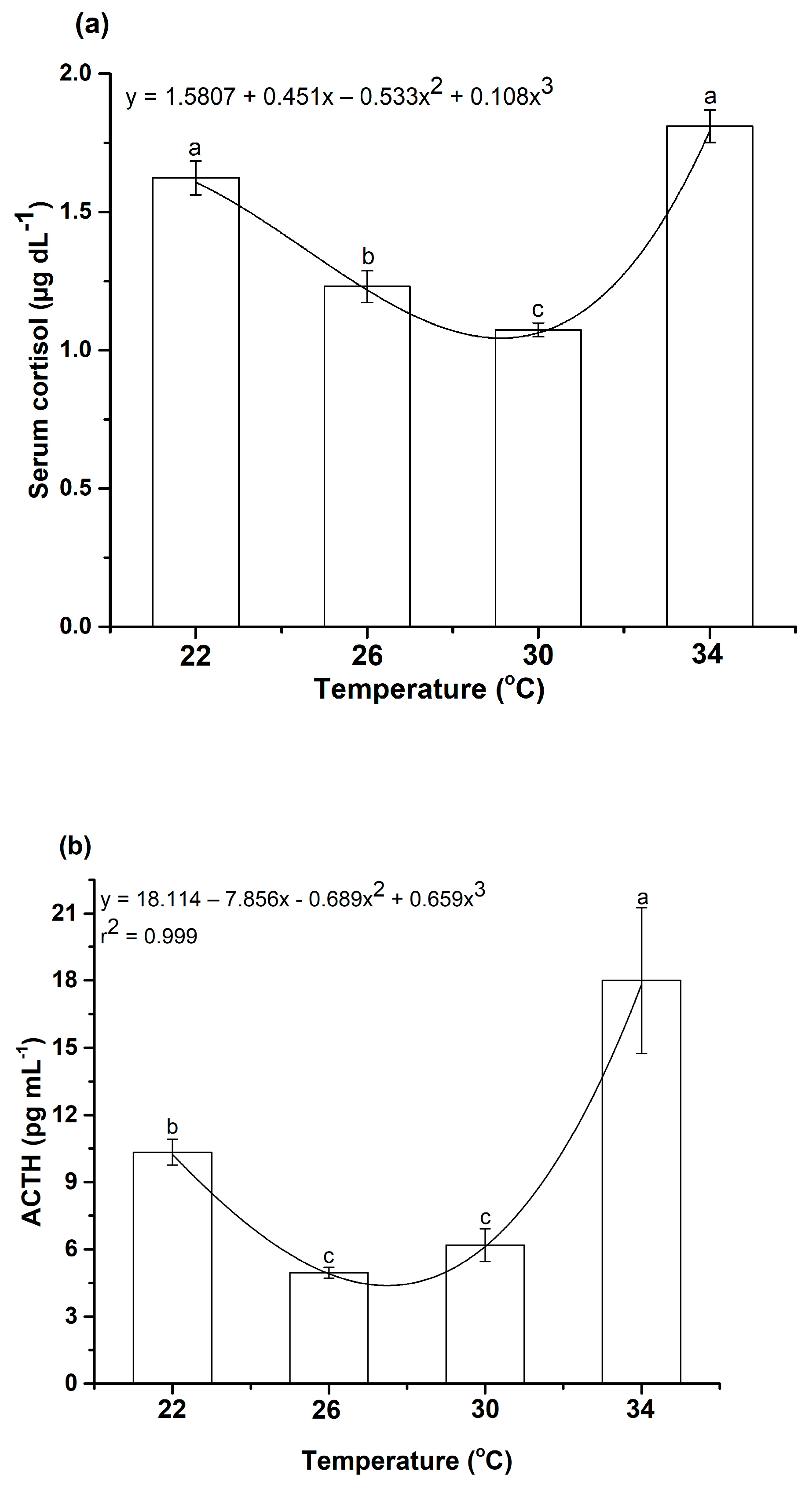

3.5.2. The Effects of Water Temperature Change on Serum Cortisol and Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) Levels

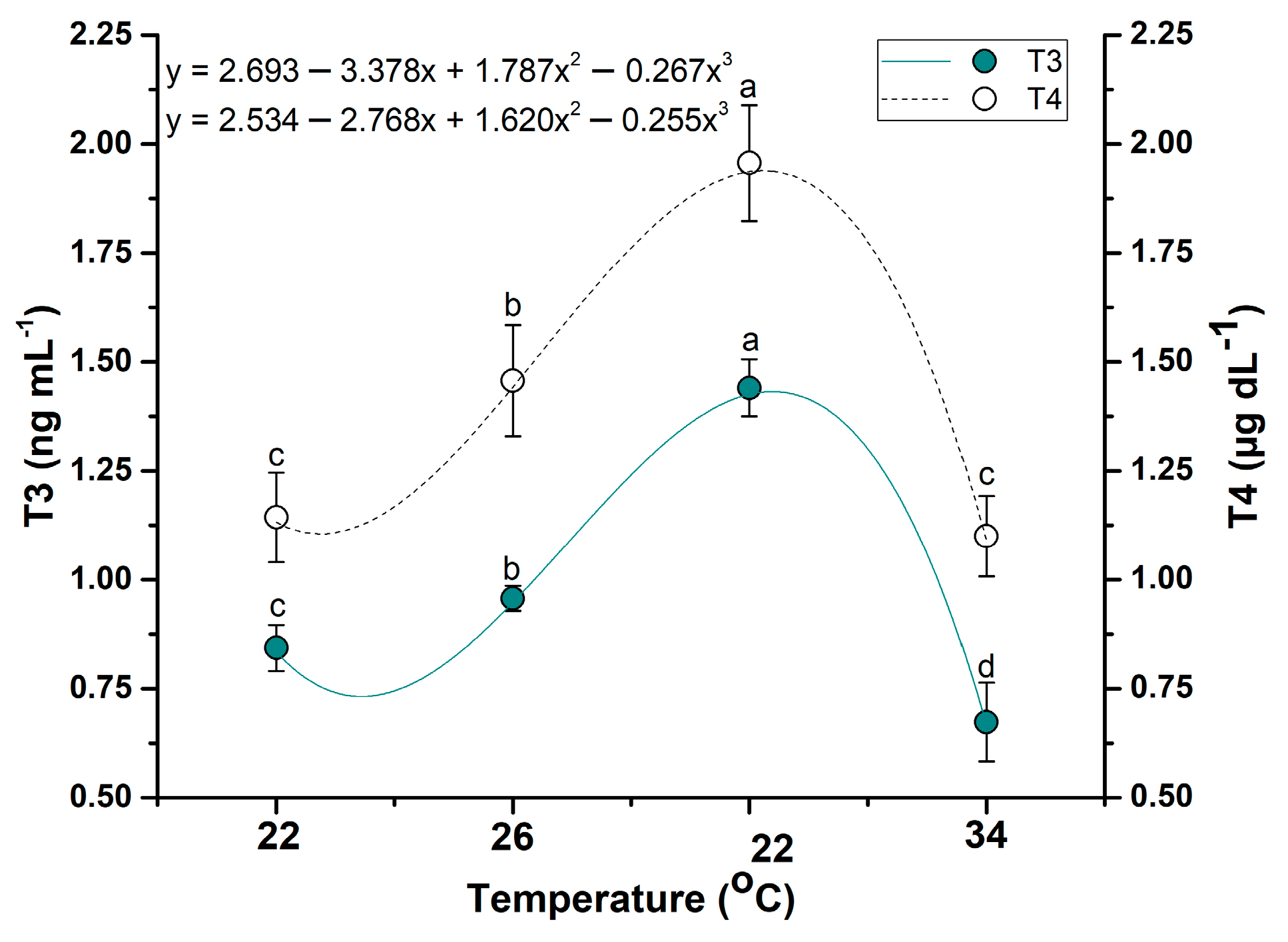

3.5.3. Effects of Water Temperature Changes on Thyroid Hormones

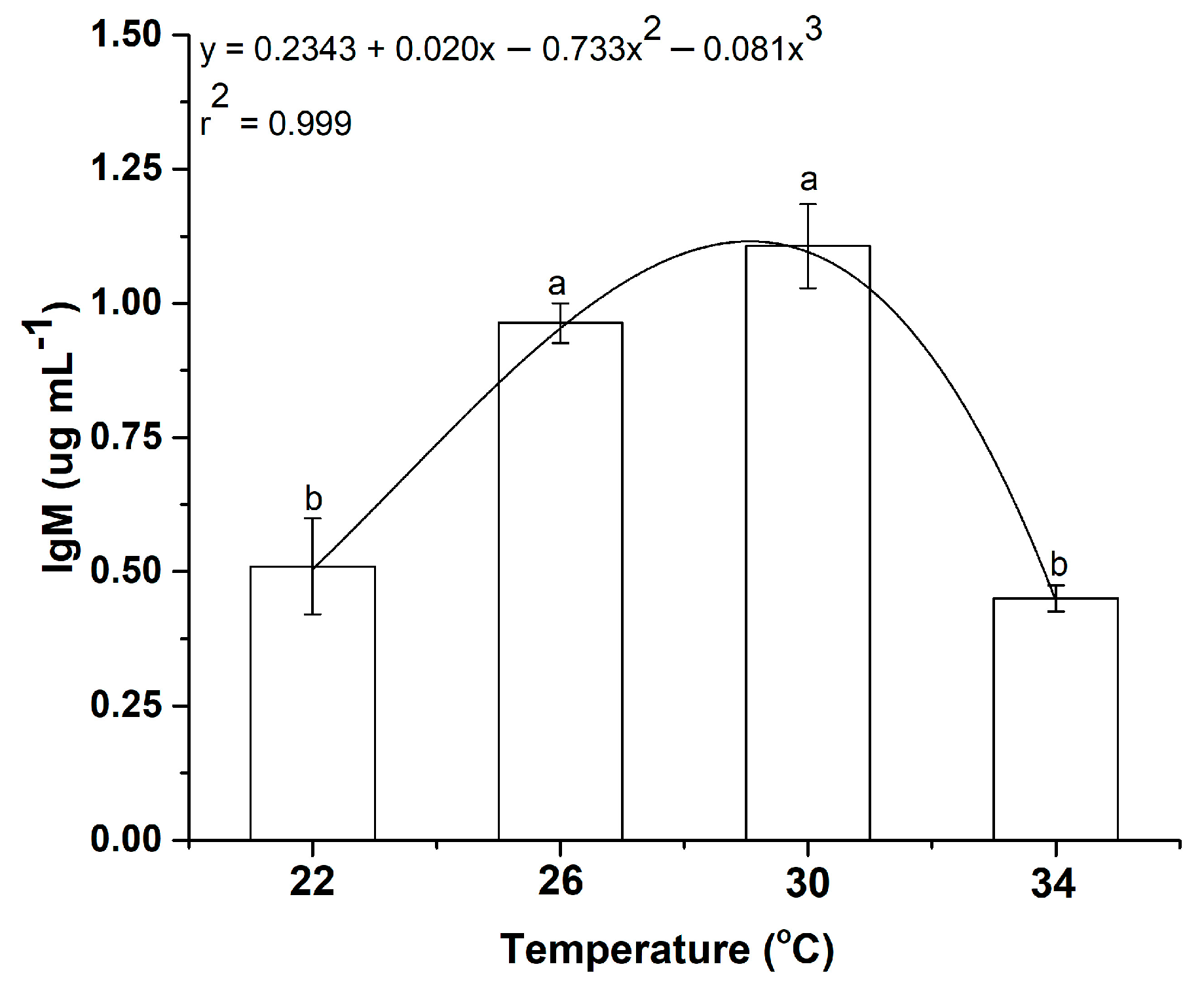

3.6. Effect of Temperature on Immunology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nur, F.; Batubara, A.; Eriani, K.; Tang, U.; Muhammada, A.A.; Siti-Azizah, M.N.; Wilkes, M.; Fadli, N.; Rizal, S.; Muchlisin, Z.A. Effect of water temperature on the physiological responses in Betta rubra, Perugia 1893 (Pisces: Osphronemidae). Int. Aquat. Res. 2020, 12, 1053. [Google Scholar]

- Lineman, M.; Do, Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Joo, G.J. Talking about climate change and global warming. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S.K.; De, M.; Mazlan, A.G.; Zaidi, C.C.; Rahim, S.M.; Simon, K.D. Impact of global climate change on fish growth, digestion and physiological status: Developing a hypothesis for cause and effect relationships. J. Water Clim. Change 2015, 6, 200–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S.K.; Ghaffar, M.A.; Das, S.K. The effects of temperature on gastric emptying time of Malabar Blood Snapper (Lutjanus malabaricus, Bloch & Schneider 1801) using X-radiography technique. AIP Conf. Proc. 2015, 1678, 020032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.J.; Prairie, Y.T. Dissolved CO2. In Encyclopedia of Inland Waters; Likens, G.E., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Doney, S.C.; Fabry, V.J.; Feely, R.A.; Kleypas, J.A. Ocean acidification: The other CO2 problem. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2009, 1, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauri, R.K.; Allen, M.R.; Barros, V.R.; Broome, J.; Cramer, W.; Christ, R.; Church, J.A.; Clarke, L.; Dahe, Q.; Dasgupta, P.; et al. Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental. In Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Hao, Y. Advanced techniques for the intelligent diagnosis of fish diseases: A review. Animals 2022, 12, 2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oczkowski, A.; McKinney, R.; Ayvazian, S.; Hanson, A.; Wigand, C.; Markham, E. Preliminary evidence for the amplification of global warming in shallow, intertidal estuarine waters. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, B.K.; Sarkar, U.K.; Bhardwaj, S.K. Assessment of habitat quality with relation to fish assemblages in an impacted river of the Ganges basin, northern India. Environmentalist 2012, 32, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjelland, M.E.; Woodley, C.M.; Swannack, T.M.; Smith, D.L. A review of the potential effects of suspended sediment on fishes: Potential dredging-related physiological, behavioral, and transgenerational implications. Environ. Sys. Dec. 2015, 35, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.D.; Blanchard, J.L.; Genner, M.G. Impacts of climate change on fish. In The Pakistan Development Review; Pakistan Institute of Development Economics: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakoso, V.A.; Pouil, S.; Cahyanti, W.; Sundari, S.; Arifin, O.Z.; Subagja, J.; Kristanto, A.H.; Slembrouck, J. Fluctuating temperature regime impairs growth in giant gourami (Osphronemus goramy) larvae. Aquaculture 2021, 539, 736606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S.K.; Das, S.K.; Bakar, Y.; Abd Ghaffar, M. Effects of temperature and diet on length-weight relationship and condition factor of the juvenile Malabar blood snapper (Lutjanus malabaricus Bloch & Schneider, 1801). J. Zhejiang Univ. 2016, 17, 580. [Google Scholar]

- Shahjahan, M.; Zahangir, M.M.; Islam, S.M.; Ashaf-Ud-Doulah, M.; Ando, H. Higher acclimation temperature affects growth of rohu (Labeo rohita) through suppression of GH and IGFs genes expression actuating stress response. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 100, 103032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howerton, R. Best Management Practices for Hawaiian Aquaculturep; Center for Tropical and Subtropical Aquaculture Publication No. 148; Center for Tropical and Subtropical Aquaculture: Waimanalo, HI, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, K.K.; Fu, C.; Qin, Y.L.; Bai, Y.; Fu, S.J. The thermal acclimation rate varied among physiological functions and temperature regimes in a common cyprinid fish. Aquaculture 2018, 495, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.J.; Kunzmann, A.; Bögner, M.; Meyer, A.; Thiele, R.; Slater, M.J. Metabolic and molecular stress responses of European seabass, Dicentrarchus labrax at low and high temperature extremes. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 112, 106118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulvault, A.L.; Barbosa, V.; Alves, R.; Custódio, A.; Anacleto, P.; Repolho, T.; Ferreira, P.P.; Rosa, R.; Marques, A.; Diniz, M. Ecophysiological responses of juvenile seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) exposed to increased temperature and dietary methylmercury. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.J.; Raby, G.D.; Teffer, A.K.; Jeffries, K.M.; Danylchuk, A.J.; Eliason, E.J.; Hasler, C.T.; Clark, T.D.; Cooke, S.J. Best practices for non-lethal blood sampling of fish via the caudal vasculature. J. Fish Biol. 2020, 97, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazio, F.; Saoca, C.; Acar, Ü.; Tezel, R.; Celik, M.; Yilmaz, S.; Kesbic, O.S.; Yalgin, F.; Yiğit, M. A comparative evaluation of hematological and biochemical parameters between the Italian mullet Mugil cephalus (Linnaeus 1758) and the Turkish mullet Chelon auratus (Risso 1810). Turk. J. Zool. 2020, 44, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, O. Thermal acclimation potential of Australian rainbow trou. In Oncorhynchus Mykiss; University of British Columbia: Kelowna, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sharmin, S.; Shahjahan, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Haque, M.A.; Rashid, H. Histopathological changes in liver and kidney of common carp exposed to sub-lethal doses of malathion. Pak. J. Zool. 2015, 47, 1495–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.A.; Uddin, M.H.; Uddin, M.J.; Shahjahan, M. Temperature changes influenced the growth performance and physiological functions of Thai pangas Pangasianodon hypophthalmus. Aquacul. Rep. 2019, 13, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, C.; White, P.; Thomas, K.; O’Maoiléidigh, N.; Fjelldal, P.G.; Hansen, T.J.; Graham, C.T.; Brophy, D. Effects of temperature and feeding regime on cortisol concentrations in scales of Atlantic salmon post-smolts. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2023, 569, 151955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, A.G.; Kunisue, T.; Kannan, K.; Seebacher, F. Thyroid hormone actions are temperature-specific and regulate thermal acclimation in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Bmc. Biol. 2013, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.R.; Habibi, H.R. Estrogen receptor function and regulation in fish and other vertebrates. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2013, 192, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.; Zamiri, M.J.; Akhlaghi, A.; Shahverdi, A.H.; Alizadeh, A.R.; Jaafarzadeh, M.R. Effect of dietary fish oil with or without vitamin E supplementation on fresh and cryopreserved ovine sperm. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2016, 57, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, T.J. Modulation of the immune system of fish by their environment. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008, 25, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kang, J.C. Oxidative stress, neurotoxicity, and metallothionein (MT) gene expression in juvenile rock fish Sebastes schlegelii under the different levels of dietary chromium (Cr6+) exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 125, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.O. Ecosystem effects of ocean acidification in times of ocean warming: A physiologist’s view. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 373, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Banerjee, S. A review on Labeo calbasu (Hamilton) with an emphasis on its conservation. J. Fish. 2015, 3, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Wahab, M.A.; Shah, M.S.; Barman, B.K.; Hoq, M.E. Habitat and fish diversity: Bangladesh perspective. In Recent advances in fisheries of Bangladesh. Ban. Fish. Res. For. Dhaka 2014, 246, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.S.; Ashaf-Ud-Doulah, M.; Hasan, M.S.; Biplob, M.S.I.; Ryhan, N.B. Effects of temperature on parameters of calbasu Labeo calbasu fingerlings at laboratory condition. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Stud. 2022, 10, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S.K.; Ghaffar, M.A.; Das, S.K. Exploring the suitable temperature and diet for growth and gastric emptying time of juvenile Malabar Blood Snapper (Lutjanus malabaricus Bloch & Schneider, 1801). Thalassas 2019, 35, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, G.L., Jr. High resolution two-dimensional polyacrylamide electrophoresis of human serum proteins. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1972, 57, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, K. Effect of partial fish meal replacement by soybean meal on the growth performance and biochemical indices of juvenile Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Aquacult. Int. 2011, 19, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Lv, Z.; Shen, J.; Wen, K. Universal simultaneous multiplex ELISA of small molecules in milk based on dual luciferases. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1001, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.; Voss, D. (Eds.) Design and Analysis of Experiments; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sokal, R.R.; Rohlf, F.J. Biometry: The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research; W.H. Freeman & Co.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Schreck, C.B.; Tort, L. The concept of stress in fish. In Fish Physiology; Academic Press: London, UK, 1941; Volume 35, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Beitinger, T.L.; Bennett, W.A.; McCauley, R.W. Temperature tolerances of North American freshwater fishes exposed to dynamic changes in temperature. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2000, 58, 237–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S.K.; Fivelstad, S.; Ghaffar, M.A.; Das, S.K. Haematological and biochemical responses of juvenile Malabar blood snapper (Lutjanus molabaricus Bloch & Schneider, 1801) exposed to different rearing temperatures and diets. Sains Malays. 2019, 48, 1790–1810. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, P.J. Dynamics of the Tropical Atmosphere and Oceans; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Katersky, R.S.; Carter, C.G. Growth efficiency of juvenile barramundi, Lates calcarifer, at high temperatures. Aquaculture 2020, 250, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.M.; Akhter, F.; Jahan, I.; Rashid, H.; Shahjahan, M. Alterations of oxygen consumption and gills morphology of Nile tilapia acclimatized to extreme warm ambient temperature. Aquacult. Rep. 2022, 23, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witeska, M.; Kondera, E.; Bojarski, B. Hematological and hematopoietic analysis in fish toxicology—A review. Animals 2023, 13, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Shukla, P. Impact of temperature variation on haematological parameters in fish Cyprinus carpio. J. Ent. Zool. Stud. 2021, 9, 134–136. [Google Scholar]

- Sikorska, J.; Kondera, E.; Kamiński, R.; Ługowska, K.; Witeska, M.; Wolnicki, J. Effect of four rearing water temperatures on some performance parameters of larval and juvenile crucian carp, Carassius carassius, under controlled conditions. Aquacult. Res. 2018, 49, 3874–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmeei, M.; Shekarabi, S.P.H.; Mehrgan, M.S.; Paknejad, H. Stimulatory effect of dietary chasteberry (Vitex agnus-castus) extract on immunity, some immune-related gene expression, and resistance against Aeromonas hydrophila infection in goldfish (Carassius auratus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 107, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheytasi, A.; Hosseini Shekarabi, S.P.; Islami, H.R.; Mehrgan, M.S. Feeding rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, with lemon essential oil loaded in chitosan nanoparticles: Effect on growth performance, serum hemato-immunological parameters, and body composition. Aquacult. Int. 2021, 29, 2207–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, S.; Ergün, S.; Çelik, E.Ş.; Banni, M.; Ahmadifar, E.; Dawood, M.A. The impact of acute cold water stress on blood parameters, mortality rate and stress-related genes in Oreochromis niloticus, Oreochromis mossambicus and their hybrids. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 100, 103049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Chacoff, L.; Arjona, F.J.; Ruiz-Jarabo, I.; García-Lopez, A.; Flik, G.; Mancera, J.M. Water temperature affects osmoregulatory responses in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata L.). J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 88, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Chacoff, L.; Arjona, F.J.; Ruiz-Jarabo, I.; Páscoa, I.; Gonçalves, O.; Martín del Río, M.P.; Mancera, J.M. Seasonal variation in osmoregulatory and metabolic parameters in earthen pond-cultured gizalthead sea bream Sparus auratus. Aquacult. Res. 2009, 40, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Gui, L.; Liu, M.; Li, W.; Hu, P.; Duarte, D.F.; Niu, H.; Chen, L. Transcriptomic responses to low temperature stress in the Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 84, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Arteaga, A.; Viegas, I.; Palma, M.; Dantagnan, P.; Valdebenito, I.; Villalobos, E.F.; Hernández, A.; Guerrero-Jiménez, J.; Metón, I.; Heyser, C. Impact of increasing temperatures on neuroendocrine and molecular responses of skeletal muscle and liver in fish: A comprehensive review. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 39, 102448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Kang, Y.; Wang, J. Transcriptomic responses to heat stress in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss head kidney. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 82, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingarro, M.; de Celis, S.V.R.; Astola, A.; Pendón, C.; Valdivia, M.M.; Pérez-Sánchez, J. Endocrine mediators of seasonal growth in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata): The growth hormone and somatolactin paradigm. Gen. Comp. Endocr. 2002, 128, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, J.; Martín, R.S.; Flores, C.; Grothusen, H.; Kausel, G. Seasonal modulation of growth hormone mRNA and protein levels in carp pituitary: Evidence for two expressed genes. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2005, 175, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, N. Blood performance: A new formula for fish growth and health. Biology 2021, 10, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mridul, M.M.I.; Zeehad, M.S.K.; Aziz, D.; Salin, K.R.; Hurwood, D.A.; Rahi, M.L. Temperature induced biological alterations in the major carp, Rohu (Labeo rohita): Assessing potential effects of climate change on aquaculture production. Aquacult. Rep. 2024, 35, 101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handeland, S.O.; Arnesen, A.M.; Stefansson, S.O. Seawater adaptation and growth of post-smolt Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) of wild and farmed strains. Aquaculture 2003, 220, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, J.N. Neuropeptides regulating the activity of goldfish corticotropes and melanotropes. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 1989, 7, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Qin, S.; He, Y.; Yang, Z.; Buchanan, T.W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, K. Cortisol awakening response predicts intrinsic functional connectivity of the medial prefrontal cortex in the afternoon of the same day. Neuroimage 2015, 122, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoul, B.; Geffroy, B. Measuring cortisol, the major stress hormone in fishes. J. Fish Biol. 2019, 94, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faught, E.; Schaaf, M.J. The mineralocorticoid receptor plays a crucial role in macrophage development and function. Endocrinology 2023, 164, bqad127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlov, D.S.; Pavlov, E.D.; Kostin, V.V.; Ganzha, E.V. Influence of water temperature on thyroid hormones and on the movement behavior of juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in water flow. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2022, 105, 1989–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G.; Sahin, T.; Hisar, O.; Hisar, S.A. Effects of low temperature and starvation on plasma cortisol, triiodothyronine, thyroxine, thyroid-stimulating hormone and prolactin levels of juvenile common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Mar. Sci. Tec. Bull. 2015, 4, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, M.; Takemura, A.; Tsuchiya, M. Effects of changes in environmental factors on the non-specific immune response of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus L. Aquacult. Res. 2005, 36, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Water Quality Parameter | Temperatures (°C) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 26 | 30 | 34 | |

| pH | 7.5 ± 0.2 a | 7.5 ± 0.4 a | 7.7 ± 0.3 a | 7.7 ± 0.2 a |

| DO (mg L−1) | 5.4 ± 0.20 a | 5.5 ± 0.14 a | 5.6 ± 0.66 a | 5.3 ± 0.19 a |

| NH3-N (mg L−1) | 0.22 ± 0.03 a | 0.24 ± 0.04 a | 0.19 ± 0.02 a | 0.15 ± 0.01 a |

| Variables | Temperature (°C) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 26 | 30 | 34 | |

| ITL | 10.38 ± 0.18 a | 9.75 ± 0.16 a | 9.97 ± 0.11 a | 10.15 ± 0.11 a |

| FTL | 10.94 ± 0.11 a | 10.74 ± 0.14 a | 11.26 ± 0.12 a | 10.87 ± 0.10 b |

| IBW | 10.6 ± 0.28 a | 9.8 ± 0.10 b | 9.71 ± 0.10389 b | 10.28 ± 0.06 a |

| FBW | 12.29 ± 0.28 b | 12.37 ± 0.25 b | 12.78 ± 0.12 a | 12.19 ± 0.11 b |

| TLG | 0.56 ± 0.11 b | 0.99 ± 0.17 a | 1.29 ± 0.15 a | 0.72 ± 0.09 b |

| BWG | 1.69 ± 0.36 b | 2.57 ± 0.21 ab | 3.07 ± 0.20 a | 1.91 ± 0.51 b |

| FCR | 1.91 ± 0.05 c | 1.62 ± 0.06 a | 1.51 ± 0.13 a | 1.83 ± 0.07 b |

| FCE | 0.52 ± 0.05 b | 0.62 ± 0.02 a | 0.66 ± 0.03 a | 0.55 ± 0.10 ab |

| CF | 0.93 ± 0.08 a | 1.02 ± 0.20 a | 0.92 ± 0.19 a | 0.96 ± 0.15 a |

| Sur | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Blood Parameter | Temperature (°C) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 26 | 30 | 34 | |

| RBC (×106 mm−3) | 0.64 ± 0.05 d | 1.05 ± 0.14 b | 1.42 ± 0.20 a | 0.85 ± 0.04 c |

| WBC | 1.73 ± 0.07 a | 1.12 ± 0.03 c | 0.86 ± 0.03 d | 1.58 ± 0.04 b |

| Haemoglobin (g dL−1) | 5.63 ± 0.12 c | 6.87 ± 0.49 b | 8.47 ± 0.81 a | 6.23 ± 0.26 b |

| HCT (%) | 17.67 ± 2.87 d | 34.33 ± 1.70 b | 42.67 ± 1.70 a | 24.00 ± 1.63 c |

| MCV | 277.87 ± 43.30 b | 332.06 ± 29.97 a | 307.69 ± 46.76 ab | 282.21 ± 26.99 b |

| MCH (pg) | 3.28 ± 0.57 a | 2.00 ± 0.06 c | 1.99 ± 0.25 c | 2.60 ± 0.12 b |

| MCHC (g dL−1) | 32.80 ± 5.65 a | 19.98 ± 0.61 b | 19.92 ± 2.49 b | 26.04 ± 1.21 a |

| PLT (×105) | 4.31 ± 0.42 a | 2.44 ± 0.16 b | 3.96 ± 0.46 a | 1.08 ± 0.02 c |

| Parameters | Temperature (°C) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 26 | 30 | 34 | |

| Total Protein (g d L−1) | 2.95 ± 0.05 a | 2.78 ± 0.04 b | 2.96 ± 0.03 a | 2.98 ± 0.03 a |

| Albumin (g d L−1) | 1.15 ± 0.05 d | 1.67 ± 0.09 b | 1.84 ± 0.05 a | 1.43 ± 0.10 c |

| Globulin (g d L−1) | 0.88 ± 0.04 c | 1.45 ± 0.05 b | 1.64 ± 0.06 a | 0.95 ± 0.05 c |

| A/G ratio | 1.32 ± 0.12 a | 1.16 ± 0.09 b | 1.12 ± 0.02 b | 1.50 ± 0.11 a |

| HCO3 (TCO3) | 28.33 ± 0.92 b | 30.77 ± 0.48 a | 30.93 ± 0.62 a | 28.83 ± 1.27 b |

| Alkaline Phosphate (AP, IU L−1) | 69.00 ± 6.48 b | 81.33 ± 3.30 a | 93.33 ± 9.39 a | 80.00 ± 8.83 a |

| Ast/SGOT (U L−1) | 16.00 ± 1.63 b | 17.67 ± 5.25 ab | 21.00 ± 4.55 a | 12.33 ± 2.05 c |

| ALT/SGPT (U L−1) | 16.07 ± 0.87 b | 17.67 ± 3.09 ab | 18.60 ± 0.54 a | 19.33 ± 1.25 a |

| Na+ (mmol L−1) | 84.57 ± 5.48 b | 89.48 ± 7.17 ab | 115.60 ± 3.72 a | 96.13 ± 4.97 b |

| K+ (mmol L−1) | 1.97 ± 0.04 b | 1.95 ± 0.07 c | 2.06 ± 0.06 a | 2.15 ± 0.04 a |

| Cl− (mmol L−1) | 59.13 ± 2.41 c | 79.43 ± 5.53 a | 78.27 ± 1.77 a | 67.10 ± 2.54 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mimi, M.S.; Das, S.K.; Rahman, M.L.; Salam, M.A.; Islam, M.N.; Rahman, T.; Das, S.R.; Hasan, M.N.; Mazumder, S.K. Physiological Responses of Kalibaus (Labeo calbasu) to Temperature Changes: Metabolic, Haemato-Biochemical, Hormonal and Immune Effects. Fishes 2026, 11, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010046

Mimi MS, Das SK, Rahman ML, Salam MA, Islam MN, Rahman T, Das SR, Hasan MN, Mazumder SK. Physiological Responses of Kalibaus (Labeo calbasu) to Temperature Changes: Metabolic, Haemato-Biochemical, Hormonal and Immune Effects. Fishes. 2026; 11(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleMimi, Masuda Sultana, Simon Kumar Das, Mohammad Lutfar Rahman, Mohammad Abdus Salam, Md. Nushur Islam, Tamanna Rahman, Sumi Rani Das, Mohammad Nazmol Hasan, and Sabuj Kanti Mazumder. 2026. "Physiological Responses of Kalibaus (Labeo calbasu) to Temperature Changes: Metabolic, Haemato-Biochemical, Hormonal and Immune Effects" Fishes 11, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010046

APA StyleMimi, M. S., Das, S. K., Rahman, M. L., Salam, M. A., Islam, M. N., Rahman, T., Das, S. R., Hasan, M. N., & Mazumder, S. K. (2026). Physiological Responses of Kalibaus (Labeo calbasu) to Temperature Changes: Metabolic, Haemato-Biochemical, Hormonal and Immune Effects. Fishes, 11(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010046