Chronic Thermal Effects on Growth, Osmoregulation, and Stress Physiology in Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) Smolt

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rearing and Seawater Acclimation

2.2. Experimental Design and Sampling Procedure

2.3. Proximate Analysis of the Entire Body

2.4. Determination of RBC Indices, Plasma Osmolality, and Plasma Na+ and Cl− Concentrations

2.5. Determination of Gill Na+/K+-ATPase Activity

2.6. Determination of Plasma Cortisol Level

2.7. Determination of Hepatic HSP70 and HSP90 mRNA Levels

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Survival

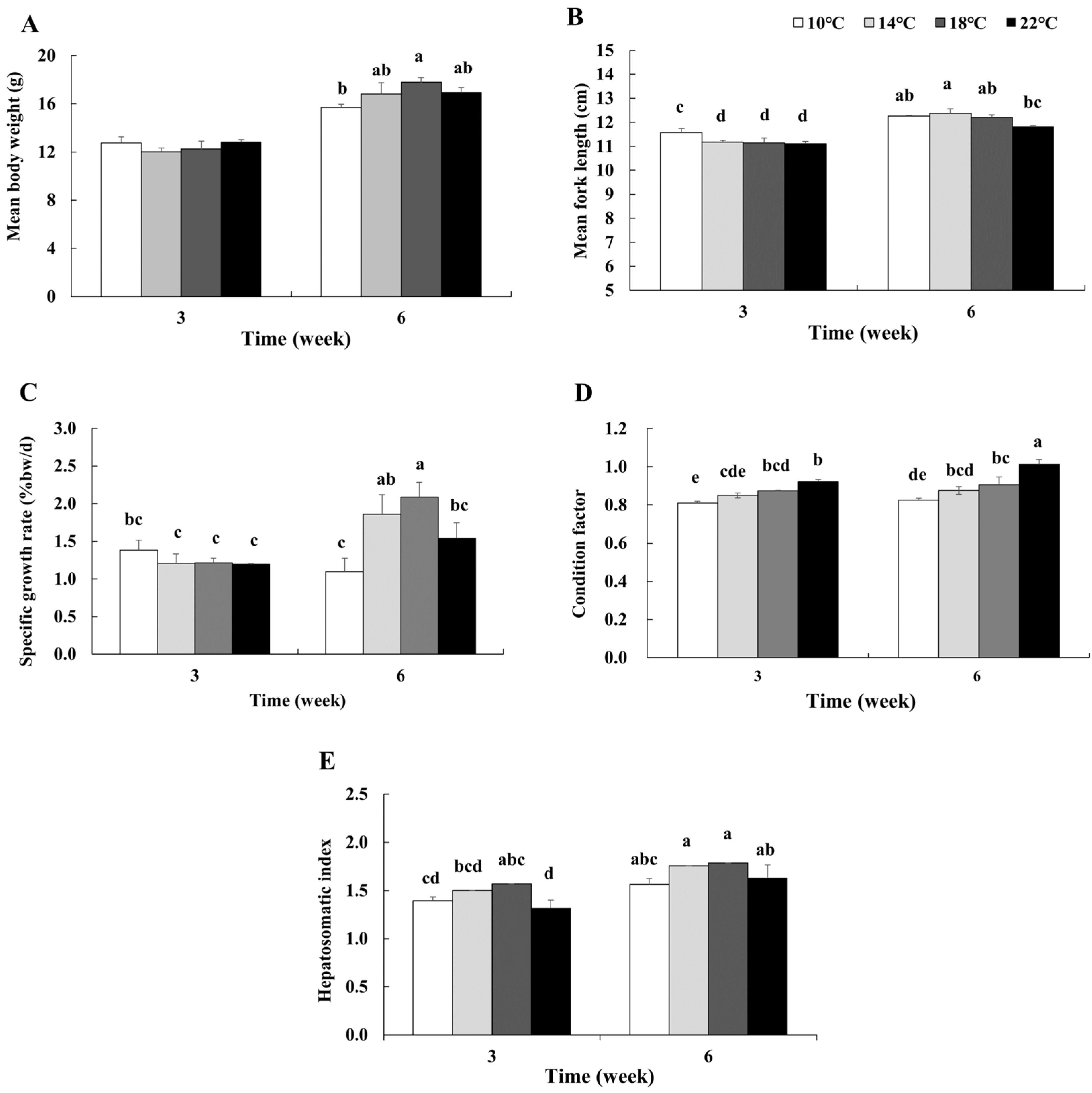

3.2. Growth Performance

3.3. Proximate Composition of the Entire Body

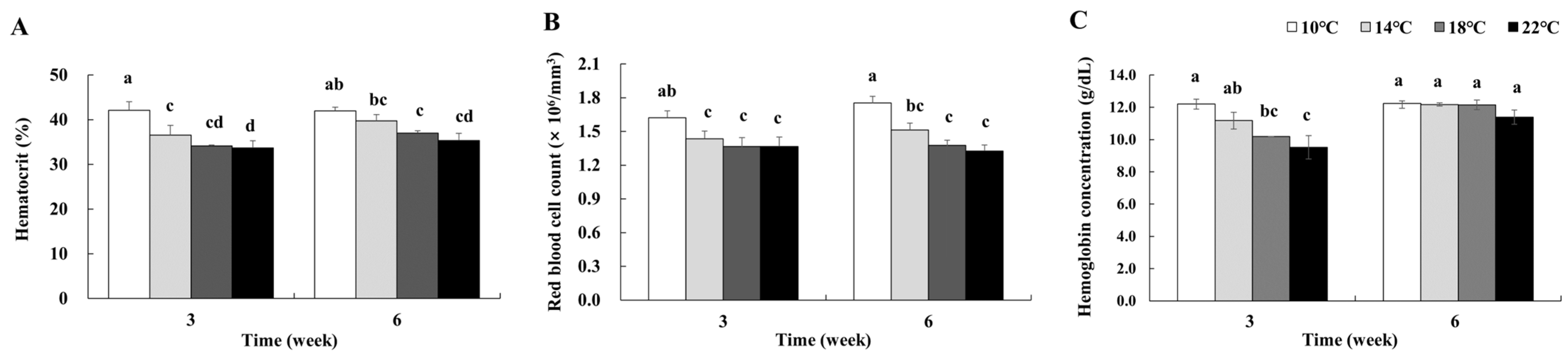

3.4. Red Blood Cell Indices

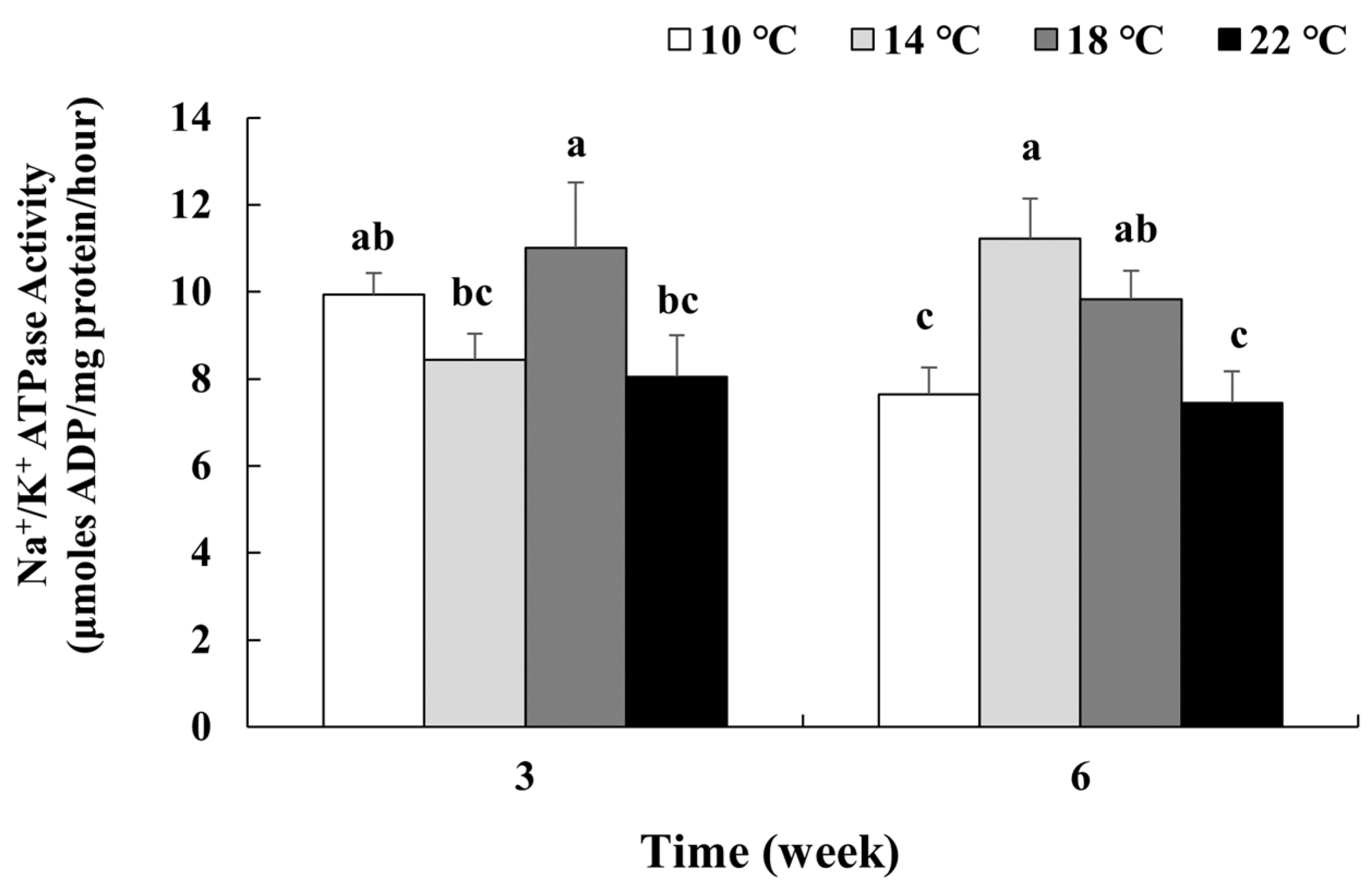

3.5. Plasma Osmolality, Na+ and Cl− Concentrations, and Gill Na+/K+-ATPase Activity

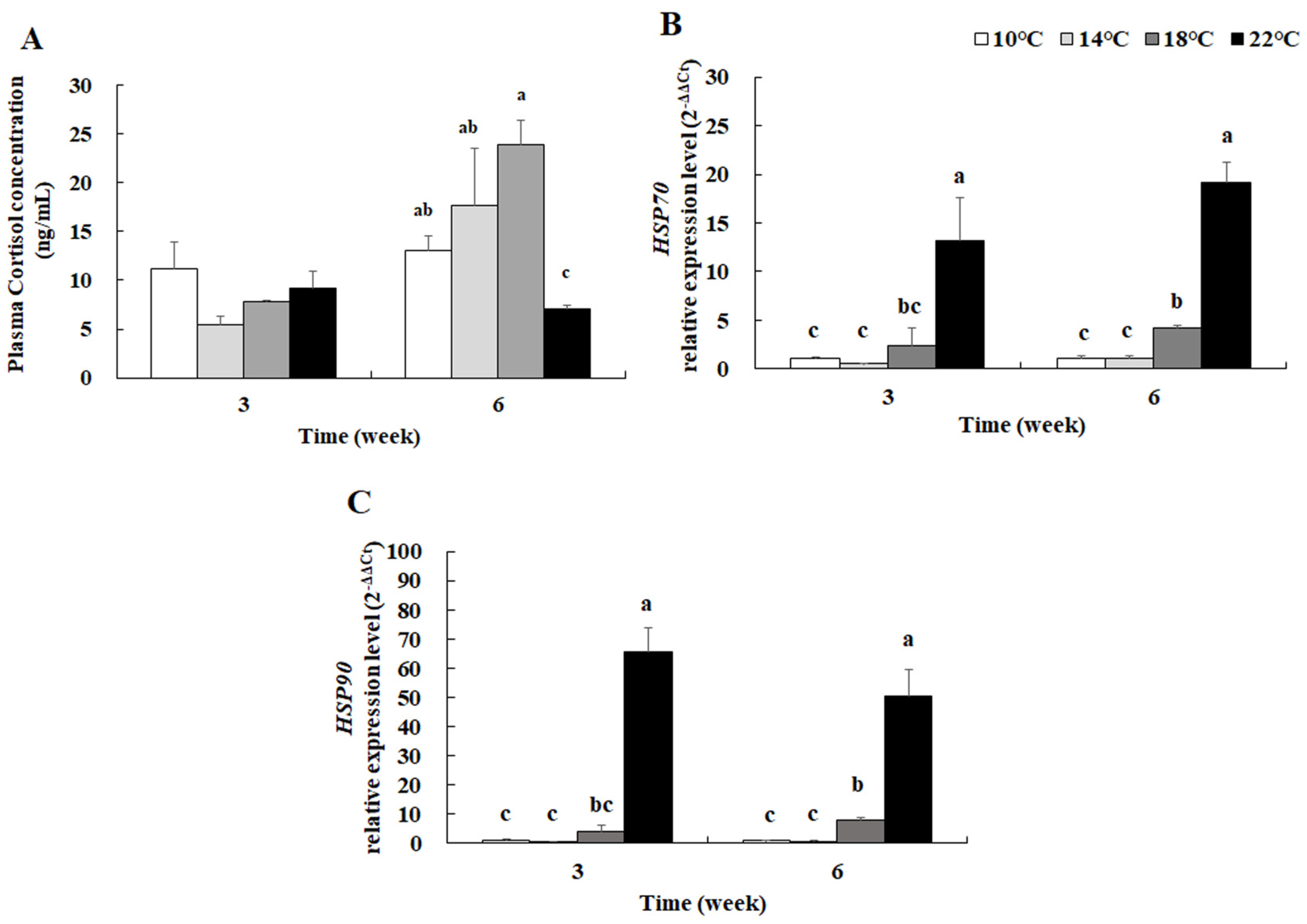

3.6. Plasma Cortisol Concentration and Hepatic Hsp70 and Hsp90 mRNA Levels

4. Discussion

4.1. Temperature Effects on Growth Parameters and Proximate Composition

4.2. RBC Indices

4.3. Osmoregulation

4.4. Plasma Cortisol Concentration and Hepatic HSP mRNA Levels

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Parameter | Weeks | Temperature (°C) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 14 | 18 | 22 | ||

| Body weight (g) | 0 | 6.75 ± 0.18 | 6.91 ± 0.30 | 6.99 ± 0.17 | 7.40 ± 0.11 |

| 3 | 12.74 ± 0.51 | 12.01 ± 0.32 | 12.24 ± 0.66 | 12.83 ± 0.17 | |

| 6 | 15.71 ± 0.26 b | 16.82 ± 0.91 ab | 17.79 ± 0.36 a | 16.94 ± 0.41 ab | |

| Fork length (cm) | 0 | 9.45 ± 0.11 | 9.41 ± 0.16 | 9.57 ± 0.08 | 9.64 ± 0.08 |

| 3 | 11.58 ± 0.16 c | 11.18 ± 0.06 d | 11.14 ± 0.21 d | 11.10 ± 0.10 d | |

| 6 | 12.27 ± 0.02 ab | 12.38 ± 0.19 a | 12.21 ± 0.10 ab | 11.83 ± 0.02 bc | |

References

- Hong, D.; Joo, G.-J.; Jung, E.; Gim, J.-S.; Seong, K.B.; Kim, D.-H.; Lineman, M.J.M.; Kim, H.-W.; Jo, H. The spatial distribution and morphological characteristics of chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) in South Korea. Fishes 2022, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitada, S.; Kishino, H. Life-stage specific effects of ocean temperatures on the hatchery chum salmon. BioRxiv 2023, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMRC (Overseas Market Research Center). Seafood Trade Statistics; KMI: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024; Available online: https://www.kfishinfo.co.kr/fisheryStatistics/domesticExImTrend.do (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Kim, B.T. An analysis of the impact of FTA Tariff elimination on the export price of Norwegian fresh and chilled salmon to Korea. J. Fish. Bus. Adm. 2018, 49, 37–48, (In Korean with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOE, Ministry of Environment, Republic of Korea. Available online: https://www.korea.kr/news/policyNewsView.do?newsId=156338199&utm_source (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Jang, J.E.; Kim, J.K.; Yoon, S.-M.; Lee, H.-G.; Lee, W.-O.; Kang, J.H.; Lee, H.J. Low genetic diversity, local-scale structure, and distinct genetic integrity of Korean chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) at the species range margin suggest a priority for conservation efforts. Evol. Appl. 2022, 15, 2142–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augerot, X. Atlas of Pacific Salmon: The First Map-Based Status Assessment of Salmon in the North Pacific; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Farley , E.V., Jr.; Yasumiishi, E.M.; Murphy, J.M.; Strasburger, W.; Sewall, F.; Howard, K.; Garcia, S.; Moss, J.H. Critical periods in the marine life history of juvenile western Alaska chum salmon in a changing climate. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2024, 726, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearcy, W.G. Ocean Ecology of the North Pacific Salmonids; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Honda, K.; Shirai, K.; Komatsu, S.; Saito, T. Sea-entry conditions of juvenile chum salmon Oncorhynchus keta that improve post-sea-entry survival: A case study of the 2012 brood-year stock released from the Kushiro River, eastern Hokkaido, Japan. Fish. Sci. 2020, 86, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Yoo, J.-T. Spatial relationship between distribution of common minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) and satellite sea surface temperature observed in the East Sea Korea in May from 2003 to 2020. J. Korean Soc. Fish. Ocean. Technol. 2022, 58, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, G.; Lee, K.-J.; Lee, S.-W.; Jin, H.; Park, J.-H. Quantification of the extremely intensified East Korea Warm Current in the summer of 2021: Offshore and coastal variabilities. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1252302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, N.; Hinch, S.G.; Eliason, E.J. Thermal tolerance in Pacific salmon: A systematic review of species, populations, life stages and methodologies. Fish Fish. 2023, 25, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, J.R. Temperature tolerance in young Pacific salmon, genus Oncorhynchus. J. Fish. Board Can. 1952, 9, 265–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, M. Evaluating Standards for Protecting Aquatic Life in Washington’s Surface Water Quality Standards: Temperature Criteria. Draft Discussion Paper and Literature Summary; Water Quality Program, Washington State Department of Ecology, Watershed Management Section: Olympia, WA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Irie, T. Ecological studies on the migration of juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta, during early ocean life. Bull. Seikai Natl. Fish. Res. Inst. 1990, 68, 1–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kurita, Y.; Saito, T.; Aritaki, M. Growth and feeding habit of chum salmon fry/juveniles in the Sanriku coastal waters, and their ecological interaction with herring larvae/juveniles. FRA salmon Res. Rep. 2010, 4, 9–11. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Torao, M. Effect of water temperature on the feed intake, growth, and feeding efficiency of juvenile Oncorhynchus keta after seawater transfer. Aquacult. Sci. 2022, 70, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Von Biela, V.R.; Regish, A.M.; Bowen, L.; Stanek, A.E.; Waters, S.; Carey, M.P.; Zimmerman, C.E.; Gerken, J.; Rinella, D.; McCormick, S.D. Differential heat shock protein responses in two species of Pacific salmon and their utility in identifying heat stress. Conserv. Physiol. 2023, 11, coad092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, J.G.; McCormick, S.D. Upper thermal limits of growth in brook trout and their relationship to stress physiology. J. Exp. Biol. 2017, 220, 3976–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, S.G.; Caissie, D.; Cunjak, R.A.; Vijayan, M.M.; Tufts, B.L. The effects of environmental heat stress on heat-shock mRNA and protein expression in Miramichi Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) parr. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2002, 59, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Chacoff, L.; Regish, A.M.; Weinstock, A.; McCormick, S.D. Effects of elevated temperature on osmoregulation and stress responses in Atlantic salmon Salmo salar smolts in fresh water and seawater. J. Fish Biol. 2018, 93, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, P.B.; Cech, J.J., Jr. Fishes: An Introduction to Ichthyology, 5th ed.; Prentice-Hall: New Jersey, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Chacoff, L.; Arjona, F.J.; Ruiz-Jarabo, I.; García-Lopez, A.; Flik, G.; Mancera, J.M. Water temperature affects osmoregulatory responses in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata L.). J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 88, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, S.D. Hormonal control of gill Na+/K+-ATPase and chloride cell function. Fish Physiol. 1995, 14, 285–315. [Google Scholar]

- Mommsen, T.P.; Vijayan, M.M.; Moon, T.W. Cortisol in teleosts: Dynamics, mechanisms of action, and metabolic regulation. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 1999, 9, 211–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedemeyer, G.A.; Saunders, R.L.; Clarke, W.C. Environmental factors affecting smoltification and early marine survival of anadromous salmonids. Mar. Fish. Rev. 1980, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, D.A. A Review and Synthesis of Effects of Alterations to the Water Temperature Regime on Freshwater Life Stages of Salmonids, with Special Reference to Oncorhynchus tshawytscha; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10: Seattle, WA, USA, 1999.

- Marine, K.R.; Cech, J.J., Jr. Effects of high water temperature on growth, smoltification, and predator avoidance in juvenile Sacramento river Chinook salmon. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2004, 24, 198–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-W.; Balasubramanian, B. Impacts of temperature on the growth, feed utilization, stress, and hemato-immune responses of cherry salmon (Oncorhynchus masou). Animals 2023, 13, 3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Lee, B.; Kim, K.; Yoon, M.; Lee, J.-W. Differential effects of two seawater transfer regimes on the hypoosmoregulatory adaptation, hormonal response, feed efficiency, and growth performance of juvenile steelhead trout. Aquac. Rep. 2022, 22, 101004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis, 16th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Hong, S.; Sun, J.-H.; Moon, J.-K.; Boo, K.-H.; Lee, S.-M.; Lee, J.-W. Toxicity of dietary selenomethionine in juvenile steelhead trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss: Tissue burden, growth performance, body composition, hematological parameters, and liver histopathology. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, S.D. Methods for nonlethal gill biopsy and measurement of Na+, K+-ATPase activity. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1993, 50, 656–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.N.; Choi, Y.J.; Lim, S.; Jeong, M.; Jin, D.-H.; Choi, C.Y. Effect of salinity changes on olfactory memory-related genes and hormones in adult chum salmon Oncorhynchus keta. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 2015, 187, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, S.D.; Glover, C.N. Acute exposure of larval rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) to elevated temperature limits hsp70b expression and influences future thermotolerance. Hydrobiologia 2019, 837, 177–187. [Google Scholar]

- Akbarzadeh, A.; Ming, T.J.; Schulze, A.D.; Kaukinen, K.H.; Li, S.; Günther, O.P.; Houde, A.L.S.; Miller, K.M. Developing molecular classifiers to detect environmental stressors, smolt stages and morbidity in coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175626. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weiss, N.A. Introductory Statistics, 9th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brett, J.R.; Shelbourn, J.E.; Shoop, C.T. Growth rate and body composition of fingerling sockeye salmon, Oncorhynchus nerka, in relation to temperature and ration size. J. Fish. Board Can. 1969, 26, 2363–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.M. The effects of temperature and ration size on the growth and energetics of salmonids in captivity. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 1982, 73, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, Y.; Kitagawa, T.; Abe, T.K.; Nagasaka, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Ota, K.; Kawashima, T.; Kawamura, T. Effect of food amount and temperature on growth rate and aerobic scope of juvenile chum salmon. Fish. Sci. 2022, 88, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.J.; Somero, G.N. Species- and tissue-specific synthesis patterns for heat-shock proteins HSP70 and HSP90 in several marine teleost fishes. Physiol. Zool. 1993, 66, 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, B.; Forseth, T.; Jensen, A.J.; Naesje, T.F. Thermal performance of juvenile Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L. Funct. Ecol. 2001, 15, 701–711. [Google Scholar]

- Eliason, E.J.; Clark, T.D.; Hague, M.J.; Hanson, L.M.; Gallagher, Z.S.; Jeffries, K.M.; Gale, M.K.; Patterson, D.A.; Hinch, S.G.; Farrell, A.P. Differences in thermal tolerance among sockeye salmon populations. Science 2011, 332, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, J.R. Some principles of the thermal requirements of fishes. Q. Rev. Biol. 1956, 31, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Lee, Y.-H.; Kim, S.; Jin, D.-H.; Seong, K.B. Genetic identification of the north Pacific chum salmon. J. Kor. Fish. Soc. 2003, 36, 578–585. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.E.; Kim, C.G.; Lee, Y.H. Genetic similarity-dissimilarity among Korea Chum salmons of each stream and their relationship with Japan salmons. Sea 2007, 12, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Myrick, C.A.; Cech, J.J., Jr. Temperature Effects on Oncorhynchus tshawytscha and Oncorhynchus mykiss: A Review Focusing on California’s Central Valley Populations; Technical Publication 01-1; California Water and Environmental Modeling Forum: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Langston, A.L.; Hoare, R.; Stefansson, M.; Fitzgerald, R.; Wergeland, H.; Mulcahy, M. The effect of temperature on non-specific defence parameters of three strains of juvenile Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus L.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2002, 12, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobling, M. Temperature and growth: Modulation of growth rate via temperature change. In Global Warming: Implications for Freshwater and Marine Fish; Society for Experimental Biology Seminar Series, 61; Wood, C.M., McDonald, D.G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; pp. 225–253. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.K.; Ern, R.; Morrison, P.R.; Brauner, C.J.; Esbaugh, A.J. Acclimation to prolonged hypoxia alters hemoglobin isoform expression and increases hemoglobin oxygen affinity and aerobic performance in a marine fish. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, M.; Kinoshita, K.; Moriyama, S.; Kurosawa, T.; Iguma, K.; Chiba, H.; Ojima, D.; Yoshinaga, T.; Arai, T. Chum salmon fry grow faster in seawater, exhibit greater activity of the GH/IGF axis, higher Na+, K+-ATPase activity, and greater gill chloride cell development. Aquaculture 2012, 362, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaro, A.; Olsen, R.E.; Kristiansen, T.S.; Ebbesson, L.O.E.; Nilsen, T.O.; Flik, G.; Gorissen, M. Stress in Atlantic salmon: Response to unpredictable chronic stress. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 218, 2538–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, P.A.; Gharbi, N.; Nilsen, T.O.; Gorissen, M.; Stefansson, S.O.; Ebbesson, L.O.E. Increased thermal challenges differentially modulate neural plasticity and stress responses in post-smolt Salmo salar. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 926136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opinion, A.G.R.; Vanhomwegen, M.; De Boeck, G.; Aerts, J. Long-term stress induced cortisol downregulation, growth reduction and cardiac remodeling in Salmo salar. J. Exp. Biol. 2023, 226, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, S.D. Smolt physiology and endocrinology. In Euryhaline Fishes; McCormick, S.D., Farrell, A.P., Brauner, C., Eds.; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 199–251. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, N.; Todgham, A.E.; Ackerman, P.A.; Bibeau, M.R.; Nakano, K.; Schulte, P.M.; Iwama, G.K. Heat shock protein genes and their functional significance in fish. Gene 2002, 295, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, J.G.; Nislow, K.H.; McCormick, S.D. Thermal onset of cellular and endocrine stress responses correspond to ecological limits in brook trout, an iconic cold-water fish. Conserv. Physiol. 2015, 3, cov017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hightower, L.E.; Norris, C.E.; DiIorio, P.J.; Fielding, E. Heat shock responses of closely related species of tropical and desert fish. Am. Zool. 1999, 39, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Ali, S.; Brraich, O.S.; Siva, C.; Pandey, P.K. State of thermal tolerance in an endangered himalayan fish Tor putitora revealed by expression modulation in environmental stress related genes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genest, O.; Wickner, S.; Doyle, S.M. Hsp90 and Hsp70 chaperones: Collaborators in protein remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 2109–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viant, M.R.; Werner, I.; Rosenblum, E.S.; Gantner, A.S.; Tjeerdema, R.S.; Johnson, M.L. Correlation between heat-shock protein induction and reduced metabolic condition in juvenile steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) chronically exposed to elevated temperature. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2003, 29, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, S.G.; Lund, E.A.M.E.A.; Tufts, B.L. Red blood cell Hsp 70 mRNA and protein as bioindicators of temperature stress in the brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2003, 60, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, S.; Gesto, M.; Sadoul, B. Temperature increase and its effects on fish stress physiology in the context of global warming. J. Fish Biol. 2021, 98, 1496–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, K. The Effects of Dissolved Oxygen on Steelhead Trout, Coho Salmon, and Chinook Salmon Biology and Function by Life Stage; Technical Report; California Regional Water Quality Control Board North Coast Region: Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, R.K.; King, H.; Carter, C.G. Hypoxia tolerance and oxygen regulation in Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar from a Tasmanian population. Aquaculture 2011, 318, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alver, M.O.; Føre, M.; Alfredsen, J.A. Predicting oxygen levels in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) sea cages. Aquaculture 2022, 548, 737720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Temperature Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 °C | 14 °C | 18 °C | 22 °C | |

| Water temperature (°C) | 10.70 ± 0.09 | 14.23 ± 0.06 | 18.29 ± 0.03 | 21.77 ± 0.08 |

| Photoperiod (L:D) | 12:12 | 12:12 | 12:12 | 12:12 |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 11.03 ± 0.10 | 9.81 ± 0.09 | 8.70 ± 0.06 | 8.24 ± 0.05 |

| pH | 8.03 ± 0.01 | 7.99 ± 0.01 | 8.08 ± 0.01 | 8.08 ± 0.01 |

| Conductivity (mS/cm) | 311.98 ± 30.04 | 389.05 ± 31.65 | 317.68 ± 33.60 | 318.03 ± 31.73 |

| Total ammonia (mg/L) † | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected |

| Nitrite (mg/L) ‡ | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected |

| Nitrate (mg/L) | 13.54 ± 1.04 | 19.79 ± 3.25 | 18.75 ± 3.26 | 19.79 ± 3.25 |

| Parameter | Time (Week) | Temperature | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 °C | 14 °C | 18 °C | 22 °C | ||

| Moisture (%) | 3 | 77.30 ± 0.07 ab | 77.36 ± 0.24 a | 76.93 ± 0.33 abc | 77.41 ± 0.15 a |

| 6 | 76.13 ± 0.09 de | 75.96 ± 0.30 e | 76.67 ± 0.03 bcd | 76.31 ± 0.20 cde | |

| Crude protein (%) | 3 | 16.23 ± 0.09 | 16.40 ± 0.29 | 16.67 ± 0.50 | 16.73 ± 0.20 |

| 6 | 16.7 ± 0.11 | 16.58 ± 0.33 | 16.66 ± 0.16 | 16.65 ± 0.12 | |

| Crude lipid (%) | 3 | 4.12 ± 0.07 bcd | 4.00 ± 0.34 cd | 3.76 ± 0.37 d | 3.0 ± 0.04 e |

| 6 | 4.70 ± 0.08 abc | 4.73 ± 0.20 ab | 5.10 ± 0.20 a | 4.13 ± 0.02 bcd | |

| Crude ash (%) | 3 | 2.17 ± 0.07 | 2.31 ± 0.09 | 2.46 ± 0.12 | 2.51 ± 0.07 |

| 6 | 2.26 ± 0.02 | 2.3 ± 0.06 | 2.23 ± 0.03 | 2.38 ± 0.03 | |

| Parameter | Time (Week) | Temperature | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 °C | 14 °C | 18 °C | 22 °C | ||

| Osmolality (mmol/kg) | 3 | 331 ± 3.61 a | 332 ± 5.28 a | 328 ± 2.33 a | 325 ± 2.79 a |

| 6 | 311 ± 5.39 b | 306 ± 1.06 b | 309 ± 3.23 b | 313 ± 3.44 b | |

| Na+ (mEq/L) | 3 | 159 ± 2.91 | 162 ± 2.12 | 162 ± 1.13 | 162 ± 0.33 |

| 6 | 163 ± 1.39 | 163 ± 0.68 | 162 ± 1.64 | 161 ± 1.26 | |

| Cl− (mEq/L) | 3 | 132 ± 2.72 | 136 ± 2.19 | 134 ± 1.47 | 136 ± 0.56 |

| 6 | 133 ± 0.24 | 132 ± 1.06 | 132 ± 0.80 | 132 ± 0.51 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balasubramanian, B.; Kim, K.; Kim, J.; Hwang, D.; Yun, E.-Y.; Kim, Y.C.; Lee, J.-W. Chronic Thermal Effects on Growth, Osmoregulation, and Stress Physiology in Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) Smolt. Fishes 2025, 10, 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120616

Balasubramanian B, Kim K, Kim J, Hwang D, Yun E-Y, Kim YC, Lee J-W. Chronic Thermal Effects on Growth, Osmoregulation, and Stress Physiology in Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) Smolt. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):616. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120616

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalasubramanian, Balamuralikrishnan, Kiyoung Kim, Junwon Kim, Doosun Hwang, Eun-Young Yun, Young Chul Kim, and Jang-Won Lee. 2025. "Chronic Thermal Effects on Growth, Osmoregulation, and Stress Physiology in Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) Smolt" Fishes 10, no. 12: 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120616

APA StyleBalasubramanian, B., Kim, K., Kim, J., Hwang, D., Yun, E.-Y., Kim, Y. C., & Lee, J.-W. (2025). Chronic Thermal Effects on Growth, Osmoregulation, and Stress Physiology in Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) Smolt. Fishes, 10(12), 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120616