The Analysis of Transitional or Caudal Vertebrae Is Equally Suitable to Determine the Optimal Dietary Phosphorus Intake to Ensure Skeletal Health and Prevent Phosphorus Waste in Salmonid Aquaculture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Location, Design, and Experimental Conditions

2.2. Diets

2.3. Sampling

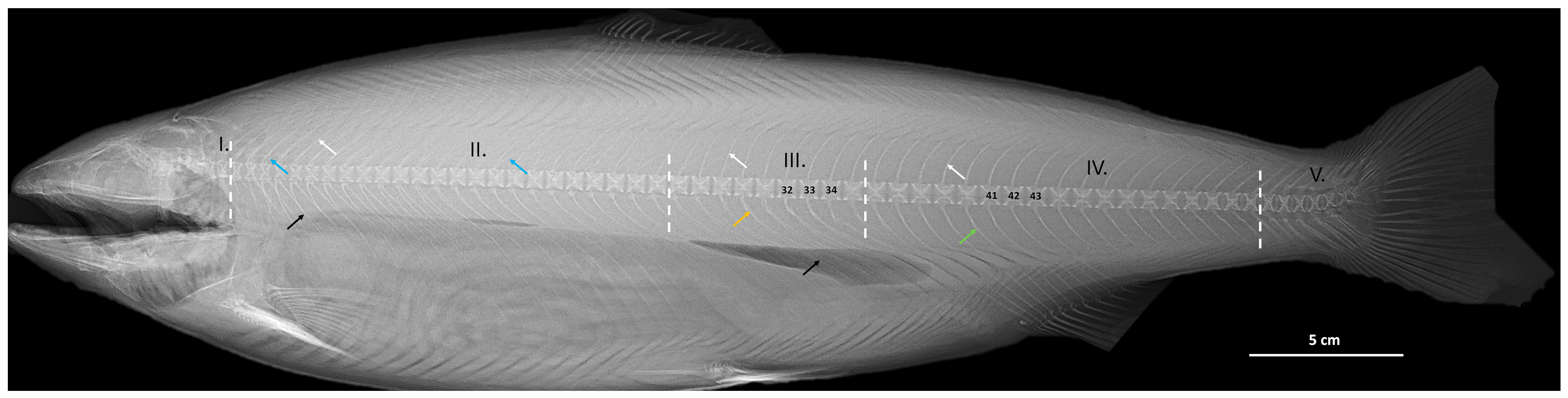

2.4. Radiography

2.5. Vertebral Centra Measurements and Compression Tests

2.6. Ash Content Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

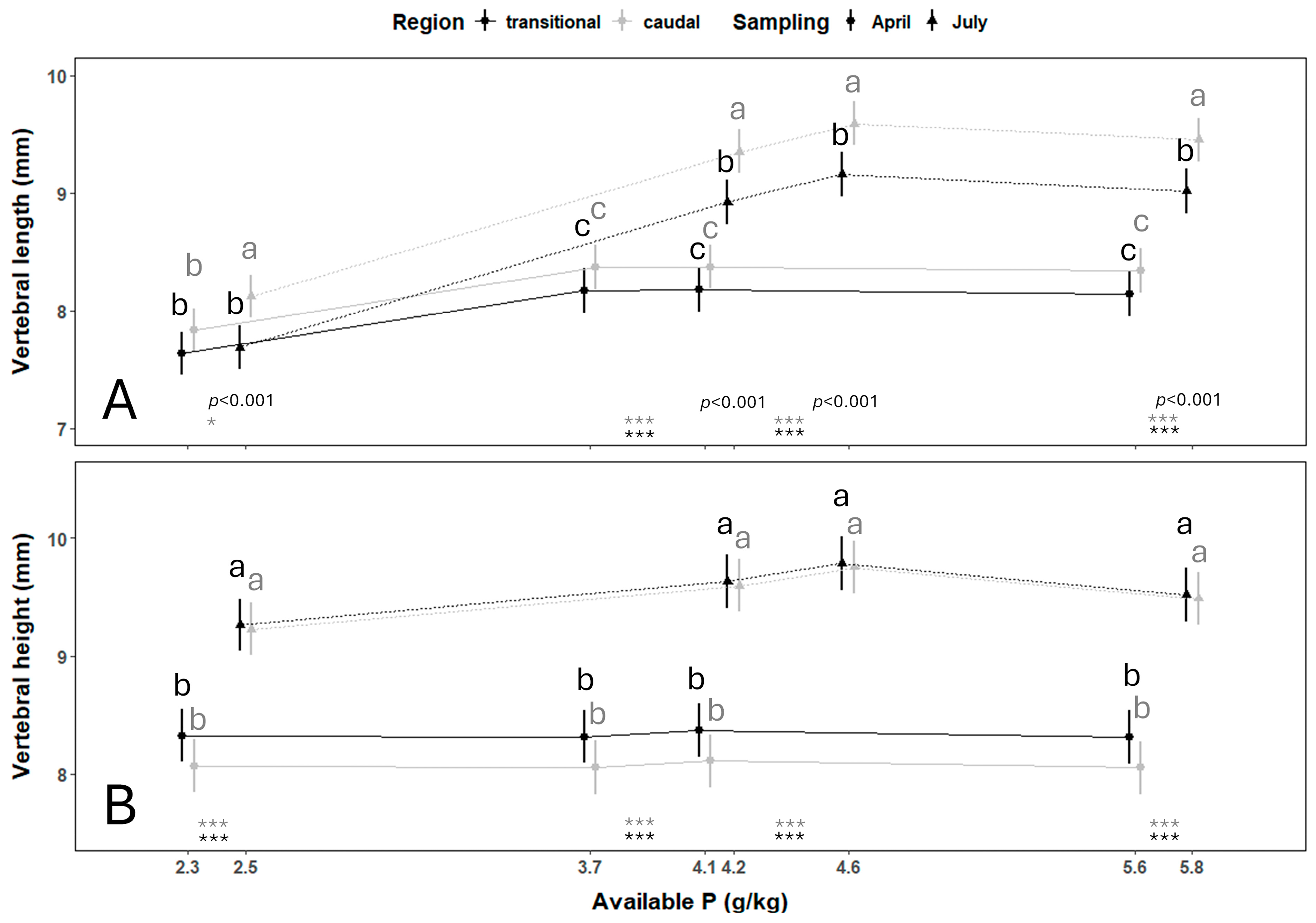

3.1. Vertebral Centra Morphometrics

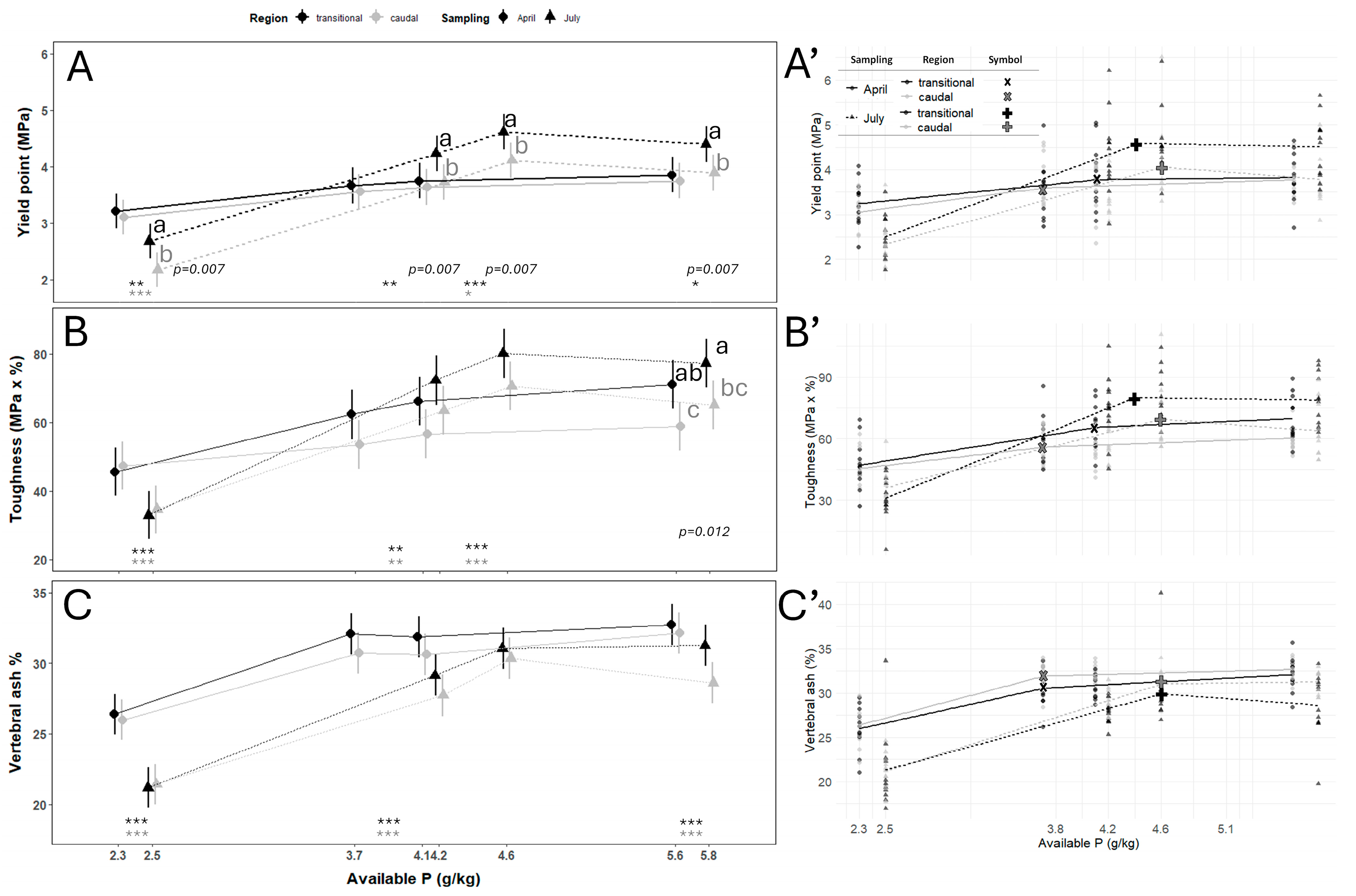

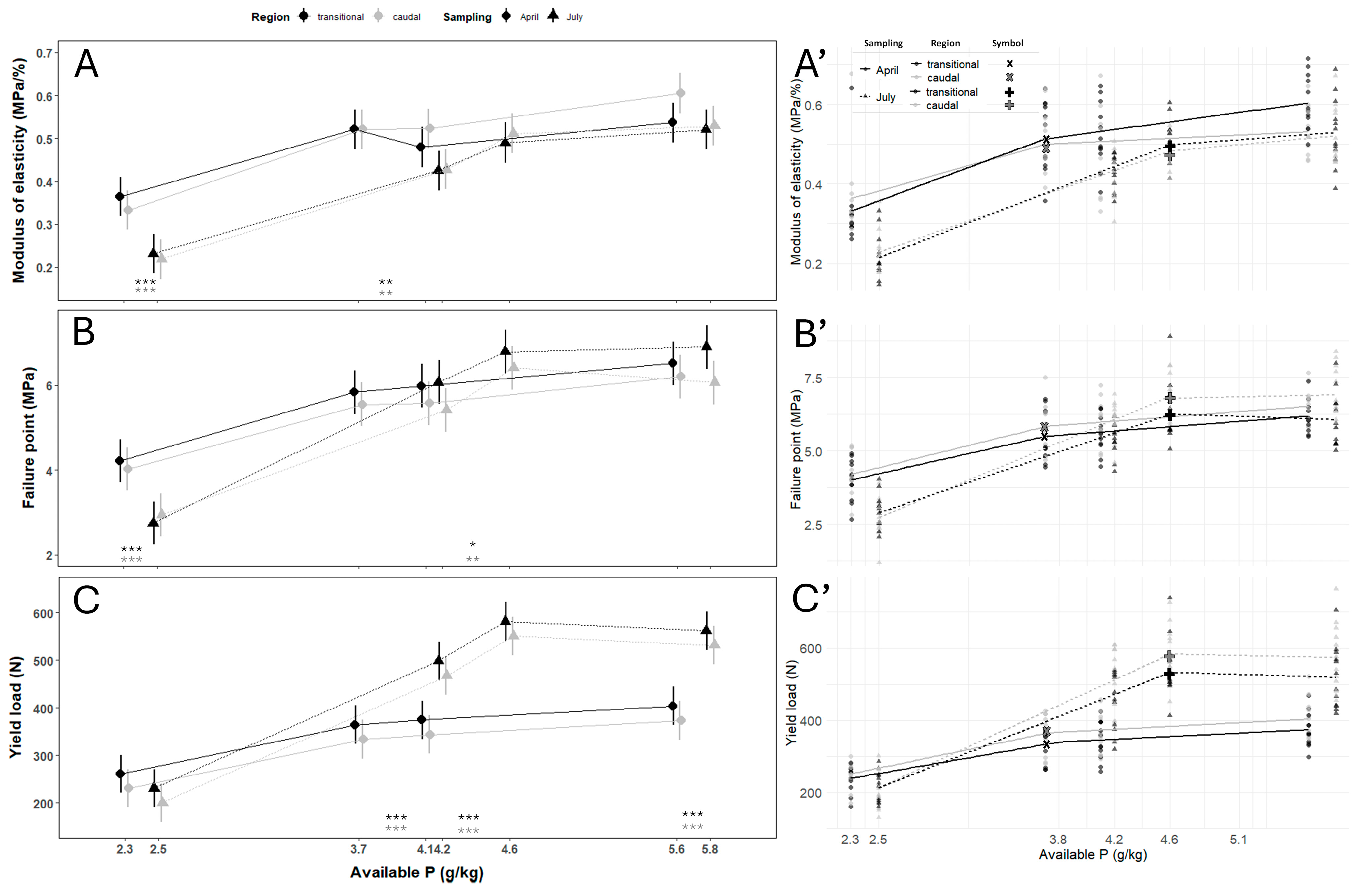

3.2. Vertebral Centra Mechanical Properties

3.3. Vertebral Centra Ash Content

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Salmon—Main Producers See Record-Breaking Exports. Available online: https://www.fao.org/in-action/globefish/news-events/news/news-detail/Salmon---Main-producers-see-record-breaking-exports/en (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Mustapha, A.; El Bakali, M. Phosphorus Waste Production in Fish Farming: A Potential for Reuse in Integrated Aquaculture Agriculture. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Res. 2021, 7, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G. Review of Waste Phosphorus from Aquaculture: Source, Removal and Recovery. Rev. Aquac. 2023, 15, 1058–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, T.S.; Åsgård, T.; Ytrestøyl, T. Utilization of Feed Resources in the Production of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) in Norway: An Update for 2020. Aquac. Rep. 2022, 26, 101316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drábiková, L.; Kröckel, S.; Witten, P.E.; Riesen, G.; Morris, P.; Ostertag, A.; Cohen-Solal, M.; Fraser, T.W.; Fjelldal, P.G. Phosphorus Requirements in Sea-Cage Farmed Atlantic salmon with an Emphasis on Bone Health and Digestibility. Aquaculture 2026, 610, 742915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, A.V.; Dittrich, N.; Strand, A.V.; Lozach, L.; Hernandez, M.L.H.; Reitan, K.I.; Müller, D.B. Circular Economy for Aquatic Food Systems: Insights from a Multiscale Phosphorus Flow Analysis in Norway. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1248984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeverfjord, G.; Åsgård, T.; Shearer, K.D. Development and Detection of Phosphorus Deficiency in Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., Parr and Post-Smolts. Aquac. Nutr. 1998, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjelldal, P.G.; Hansen, T.; Breck, O.; Sandvik, R.; Waagbø, R.; Berg, A.; Ørnsrud, R. Supplementation of Dietary Minerals During the Early Seawater Phase Increases Vertebral Strength and Reduces the Prevalence of Vertebral Deformities in Fast-Growing Under-Yearling Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) Smolt. Aquac. Nutr. 2009, 15, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjelldal, P.G.; Hansen, T.J.; Lock, E.J.; Wargelius, A.; Fraser, T.W.K.; Sambraus, F.; El-Mowafi, A.; Albrektsen, S.; Waagbø, R.; Ørnsrud, R. Increased Dietary Phosphorus Prevents Vertebral Deformities in Triploid Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Aquac. Nutr. 2016, 22, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjelldal, P.G.; Lock, E.J.; Hansen, T.; Waagbø, R.; Wargelius, A.; Gil Martens, L.; El-Mowafi, A.; Ørnsrud, R. Continuous Light Induces Bone Resorption and Affects Vertebral Morphology in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) Fed a Phosphorus Deficient Diet. Aquac. Nutr. 2012, 18, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, P.E.; Owen, M.A.G.; Fontanillas, R.; Soenens, M.; McGurk, C.; Obach, A. A Primary Phosphorus-Deficient Skeletal Phenotype in Juvenile Atlantic salmon Salmo salar: The Uncoupling of Bone Formation and Mineralization. J. Fish Biol. 2016, 88, 690–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, T.W.K.; Witten, P.E.; Albrektsen, S.; Breck, O.; Fontanillas, R.; Nankervis, L.; Thomsen, T.H.; Koppe, W.; Sambraus, F.; Fjelldal, G. Phosphorus Nutrition in Farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar): Life Stage and Temperature Effects on Bone Pathologies. Aquaculture 2019, 511, 734246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drábiková, L.; Fjelldal, P.G.; De Clercq, A.; Yousaf, M.N.; Morken, T.; McGurk, C.; Witten, P.E. Vertebral Column Adaptations in Juvenile Atlantic salmon Salmo salar, L. as a Response to Dietary Phosphorus. Aquaculture 2021, 541, 736776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åsgård, T.; Shearer, K.D. Dietary Phosphorus Requirement of Juvenile Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L. Aquac. Nutr. 1997, 3, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjelldal, P.G.; Hansen, T.; Albrektsen, S. Inadequate Phosphorus Nutrition in Juvenile Atlantic Salmon Has a Negative Effect on Long-Term Bone Health. Aquaculture 2012, 334–337, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Martens, L.; Fjelldal, P.G.; Lock, E.J.; Wargelius, A.; Wergeland, H.; Witten, P.E.; Hansen, T.; Waagbø, R.; Ørnsrud, R. Dietary Phosphorus Does Not Reduce the Risk for Spinal Deformities in a Model of Adjuvant-Induced Inflammation in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) Postsmolts. Aquac. Nutr. 2012, 18, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, A.; Perrott, M.R.; Davie, P.S.; Preece, M.A.; Wybourne, B.; Ruff, N.; Huysseune, A.; Witten, P.E. Vertebral Column Regionalisation in Chinook salmon, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha. J. Anat. 2017, 231, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, M.; Kryvi, H.; Fraser, T.W.K.; Philip, A.J.P.; Remø, S.; Hansen, T.J.; Witten, P.E.; Fjelldal, P.G. A New Method for Regionalization of the Vertebral Column in Salmonids Based on Radiographic Hallmarks. J. Fish Biol. 2024, 105, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze, H.-P.; Arratia, G. The Caudal Skeleton of Basal Teleosts, Its Conventions, and Some of Its Major Evolutionary Novelties in a Temporal Dimension. In Mesozoic Fishes 5—Global Diversity and Evolution; Arratia, G., Schultze, H.-P., Wilson, M.V.H., Eds.; Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil: München, Germany, 2013; pp. 187–246. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, R. On the Archetype and Homologies of the Vertebrate Skeleton; Richard & John E. Taylor: London, UK, 1848. [Google Scholar]

- Fjelldal, P.G.; Grotmol, S.; Kryvi, H.; Gjerdet, N.R.; Taranger, G.L.; Hansen, T.; Porter, M.J.R.; Totland, G.K. Pinealectomy Induces Malformation of the Spine and Reduces the Mechanical Strength of the Vertebrae in Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar. J. Pineal Res. 2004, 36, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, S.J.; Mehrle, P.M.; Mayer, F.L.; Jones, J.R. Method to Evaluate Mechanical Properties of Bone in Fish. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1981, 110, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, P.E.; Fjelldal, P.G.; Huysseune, A.; McGurk, C.; Obach, A.; Owen, M.A.G. Bone without Minerals and Its Secondary Mineralization in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar): The Recovery from Phosphorus Deficiency. J. Exp. Biol. 2019, 222, jeb188763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drábiková, L.; De Clercq, A.; Yousaf, M.N.; Morken, T.; McGurk, C.; Witten, P.E. What Will Happen to My Smolt at Harvest? Individually Tagged Atlantic Salmon Help to Understand Possible Progression and Regression of Vertebral Deformities. Aquaculture 2022, 560, 738430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfakiotakis, M.; Lane, D.M.; Davies, J.B.C. Review of Fish Swimming Modes for Aquatic Locomotion. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 1999, 24, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjelldal, P.G.; Nordgarden, U.; Berg, A.; Grotmol, S.; Totland, G.K.; Wargelius, A.; Hansen, T. Vertebrae of the Trunk and Tail Display Different Growth Rates in Response to Photoperiod in Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., Post-Smolts. Aquaculture 2005, 250, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solstorm, F.; Solstorm, D.; Oppedal, F.; Fjelldal, P.G. The Vertebral Column and Exercise in Atlantic salmon—Regional Effects. Aquaculture 2016, 461, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, A.P.; Beall, E. Energy Use in Spawning Atlantic Salmon. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2004, 13, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorstad, E.B.; Whoriskey, F.; Uglem, I.; Moore, A.; Rikardsen, A.H.; Finstad, B. A Critical Life Stage of the Atlantic salmon Salmo salar: Behaviour and Survival During the Smolt and Initial Post-Smolts Migration. J. Fish Biol. 2012, 81, 500–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witten, P.E.; Gil-Martens, L.; Huysseune, A.; Takle, H.; Hjelde, K. Towards a Classification and an Understanding of Developmental Relationships of Vertebral Body Malformations in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Aquaculture 2009, 295, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kültz, D. Physiological Mechanisms Used by Fish to Cope with Salinity Stress. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 218, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Long, J.H. Vertebrae in Compression: Mechanical Behavior of Arches and Centra in the Gray Smooth-Hound Shark (Mustelus californicus). J. Morphol. 2010, 271, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grini, A.; Hansen, T.; Berg, A.; Wargelius, A.; Fjelldal, P.G. The Effect of Water Temperature on Vertebral Deformities and Vaccine-Induced Abdominal Lesions in Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L. J. Fish Dis. 2011, 34, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, J.; Bates, D.; DebRoy, S.; Sarkar, D.; R Core Team. Nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Bartoń, K. MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference, R Package Version 1.46.0. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Hurvich, C.M.; Tsai, C.L. Bias of the Corrected AIC Criterion for Underfitted Regression and Time Series Models. Biometrika 1991, 78, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. Nonlinear Regression, Nonlinear Least Squares, and Nonlinear Mixed Models in R. In An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Muggeo, V.M. segmented: An R Package to Fit Regression Models with Broken-Line Relationships. R News 2008, 8, 20–25. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/doc/Rnews/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Lenth, R. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means, R Package Version 1.10.5-0900003. Available online: https://rvlenth.github.io/emmeans/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; p. XVI, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totland, G.K.; Fjelldal, P.G.; Kryvi, H.; Løkka, G.; Wargelius, A.; Sagstad, A.; Hansen, T.; Grotmol, S. Sustained Swimming Increases the Mineral Content and Osteocyte Density of Salmon Vertebral Bone. J. Anat. 2011, 219, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witten, P.E.; Hall, B.K. Teleost Skeletal Plasticity: Modulation, Adaptation, and Remodelling. Copeia 2015, 103, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viguet-Carrin, S.; Garnero, P.; Delmas, P.D. The Role of Collagen in Bone Strength. Osteoporos. Int. 2006, 17, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currey, J.D. Role of Collagen and Other Organics in the Mechanical Properties of Bone. Osteoporos. Int. 2003, 14, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotti, S.; Huysseune, A.; Koppe, W.; Rücklin, M.; Marone, F.; Wölfel, E.; Fiedler, I.; Busse, B.; Forlino, A.; Witten, P. More bone with less minerals? The effects of dietary phosphorus on the post-cranial skeleton in zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.; Reid, S.W.J.; Ternent, H.; Manchester, N.J.; Roberts, R.J.; Stone, D.A.J.; Hardy, R.W. The Aetiology of Spinal Deformity in Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L.: Influence of Different Commercial Diets on the Incidence and Severity of the Preclinical Condition in Salmon Parr under Two Contrasting Husbandry Regimes. J. Fish Dis. 2007, 30, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smedley, M.A.; Migaud, H.; McStay, E.L.; Clarkson, M.; Bozzolla, P.; Campbell, P.; Taylor, J.F. Impact of Dietary Phosphorus in Diploid and Triploid Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) with Reference to Early Skeletal Development in Freshwater. Aquaculture 2018, 490, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjelldal, P.G.; Nordgarden, U.; Hansen, T. The Mineral Content Affects Vertebral Morphology in Underyearling Smolt of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Aquaculture 2007, 270, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laerm, J. The Development, Function, and Design of Amphicoelous Vertebrae in Teleost Fishes. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 1976, 58, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, P.E.; Gil-Martens, L.; Hall, B.K.; Huysseune, A.; Obach, A. Compressed Vertebrae in Atlantic Salmon Salmo salar: Evidence for Metaplastic Chondrogenesis as a Skeletogenic Response Late in Ontogeny. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2005, 64, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, P.E.; Obach, A.; Huysseune, A.; Bæverfjord, G. Vertebrae Fusion in Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar): Development, Aggravation and Pathways of Containment. Aquaculture 2006, 258, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashhurst, D.E. The Cartilaginous Skeleton of an Elasmobranch Fish Does Not Heal. Matrix Biol. 2004, 23, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Baez, J.C.; Simpson, D.J.; LLeras Forero, L.; Zeng, Z.; Brunsdon, H.; Salzano, A.; Brombin, A.; Wyatt, C.; Rybski, W.; Huitema, L.F.; et al. Wilms Tumor 1b Defines a Wound-Specific Sheath Cell Subpopulation Associated with Notochord Repair. eLife 2018, 7, e30657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, P.E.; Hall, B.K. The Notochord: Development, Evolution and Contributions to the Vertebral Column, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; 266p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Guerrero, R.; Baeverfjord, G.; Evensen, Ø.; Hamre, K.; Larsson, T.; Dessen, J.E.; Gannestad, K.H.; Mørkøre, T. Rib Abnormalities and Their Association with Focal Dark Spots in Atlantic salmon Fillets. Aquaculture 2022, 561, 738697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.R.; Van der Meulen, M.C.H.; Beaupré, G.S. Mechanical Factors in Bone Growth and Development. Bone 1996, 18, S5–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urist, M.R.; Johnson, R.W. Calcification and Ossification: IV. The Healing of Fractures in Man under Clinical Conditions. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1943, 25, 375–426. [Google Scholar]

- Albrektsen, S.; Hope, B.; Aksnes, A. Phosphorous (P) deficiency due to low P availability in fishmeal produced from blue whiting (Micromesistius poutassou) in feed for under-yearling Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) smol. Aquaculture 2009, 296, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phleger, C.F.; Wambeke, S.R. Bone lipids and fatty acids of Peru Fish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 1994, 109, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, S.H.; McDaniel, N.K.; Ferraris, R.P. In Vivo Fractional Pi Absorption and NaPi-II mRNA Expression in Rainbow Trout Are Upregulated by Diteray P Restriction. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2003, 285, R770–R781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, S.H. Digestion and Absorption of Dietary Phosphorus in Fish. Fishes 2024, 9, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drábiková, L.; Fjelldal, P.G.; Yousaf, M.N.; Morken, T.; De Clercq, A.; McGurk, C.; Witten, P.E. Elevated Water CO2 Can Prevent Dietary-Induced Osteomalacia in Post-smolt Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar, L.). Biomolecules 2023, 13, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taketani, Y.; Segawa, H.; Chikamori, M.; Morita, K.; Tanaka, K.; Kido, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Iemori, Y.; Tatsumi, S.; Tsugawa, N.; et al. Regulation of Type II Renal Na+-Dependent Inorganic Phosphate Transporters by 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3. Identification of a Vitamin D-Responsive Element in the Human NaPi-3 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 14575–14581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundell, K.; Norman, A.W.; Björnsson, B.T. 1,25(OH)2 Vitamin D3 Increases Ionized Plasma Calcium Concentrations in the Immature Atlantic cod Gadus morhua. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1993, 91, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, S.; Metcalfe, N.B.; Huntingford, F.A.; Thorpe, J.E. What controls the onset of anorexia in maturing adult female Atlantic salmon? Funct. Ecol. 1995, 9, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling | Vertebral Column Region | Estimated Dietary P Requirements (g/kg) | 95% Confidence Intervals | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield point | ||||

| April | Transitional | 4.1 | (1.91–6.28) | 0.1 |

| Caudal | 3.7 | (2.02–5.38) | 0.013 | |

| July | Transitional | 4.4 | (3.83–5.02) | <0.001 |

| Caudal | 4.6 | (4.03–5.17) | <0.001 | |

| Toughness | ||||

| April | Transitional | 4.1 | (2.63–5.57) | 0.003 |

| Caudal | 3.7 | (1.91–5.49) | 0.01 | |

| July | Transitional | 4.4 | (3.93–4.86) | <0.001 |

| Caudal | 4.6 | (4.06–5.14) | <0.001 | |

| Vertebral ash | ||||

| April | Transitional | 3.7 | (3.27–4.13) | <0.001 |

| Caudal | 3.7 | (2.93–4.47) | ||

| July | Transitional | 4.6 | (4.30–4.92) | |

| Caudal | 4.6 | (3.97–5.23) | ||

| Sampling | Vertebral Column Region | Estimated Dietary P Requirements (g/kg) | 95% Confidence Intervals | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modulus of elasticity | ||||

| April | Transitional | 3.7 | (2.63–4.77) | <0.001 |

| Caudal | 3.7 | (2.71–4.69) | ||

| July | Transitional | 4.6 | (4.01–5.19) | |

| Caudal | 4.6 | (4.06–5.14) | ||

| Failure point | ||||

| April | Transitional | 3.7 | (2.83–4.58) | <0.001 |

| Caudal | 3.7 | (2.76–4.63) | ||

| July | Transitional | 4.6 | (4.18–4.95) | |

| Caudal | 4.6 | (4.16–5.04) | ||

| Yield load | ||||

| April | Transitional | 3.7 | (2.89–4.54) | <0.001 |

| Caudal | 3.8 | (2.88–4.68) | ||

| July | Transitional | 4.6 | (4.19–5.01) | |

| Caudal | 4.6 | (4.17–5.03) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hersi, M.A.; Fraser, T.W.K.; Kröckel, S.; Fjelldal, P.G.; Drábiková, L. The Analysis of Transitional or Caudal Vertebrae Is Equally Suitable to Determine the Optimal Dietary Phosphorus Intake to Ensure Skeletal Health and Prevent Phosphorus Waste in Salmonid Aquaculture. Fishes 2025, 10, 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120617

Hersi MA, Fraser TWK, Kröckel S, Fjelldal PG, Drábiková L. The Analysis of Transitional or Caudal Vertebrae Is Equally Suitable to Determine the Optimal Dietary Phosphorus Intake to Ensure Skeletal Health and Prevent Phosphorus Waste in Salmonid Aquaculture. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):617. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120617

Chicago/Turabian StyleHersi, Mursal Abdulkadir, Thomas William Kenneth Fraser, Saskia Kröckel, Per Gunnar Fjelldal, and Lucia Drábiková. 2025. "The Analysis of Transitional or Caudal Vertebrae Is Equally Suitable to Determine the Optimal Dietary Phosphorus Intake to Ensure Skeletal Health and Prevent Phosphorus Waste in Salmonid Aquaculture" Fishes 10, no. 12: 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120617

APA StyleHersi, M. A., Fraser, T. W. K., Kröckel, S., Fjelldal, P. G., & Drábiková, L. (2025). The Analysis of Transitional or Caudal Vertebrae Is Equally Suitable to Determine the Optimal Dietary Phosphorus Intake to Ensure Skeletal Health and Prevent Phosphorus Waste in Salmonid Aquaculture. Fishes, 10(12), 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120617