1. Introduction

This paper analyzes the concept of need in Carl Menger’s value theory and relates it to some philosophical theories dealing with the same concept from an anthropological point of view. To carry out this analytical itinerary, we take the point of view developed by Vara [

1], who states that all economic theories imply a specific philosophy, where both a worldview and an anthropological conception are supposed.

1 Vara showed how this implicit philosophy, with its respective anthropology, models in a

pre-theoretical way the conception of the “economic agent” in the most relevant economic schools. This happens because “economists—says Vara—cannot get rid, at the moment of doing their work, of certain preconceptions of reality that they carry with them.” He argues: “What is more, it seems that these preconceptions are mainly centered on the concept of economic agent that they define and, therefore, they incorporate judgments that are, above all, of a philosophical nature” [

1] (p. 17).

Indeed, the general process of production should be understood, according to Vara, as a derivative “of a

personal process of production made by the person who acts or allocates [resources] and that is, in essence, the most fundamental and determining,” which implies “the operation of an anthropological type of presupposition that is taken as a systematic principle of behavior” [

1] (pp. 28–29). Finally, this anthropological presupposition goes into the respective theory. However, concerning the figure of the “economic agent,” we need to consider that every theory must construct a simplified model of reality, in this case, a model of a person and their behavior: “In economic theory a simplified version of it is adopted: the ‘economic agent.’ This consists of a mental recreation of what a human being is, with the characteristic of being useful and operative for theoretical analysis” [

1] (p. 29).

With this in mind, our aim is to investigate the implicit content of the economic agent in Carl Menger’s theory, as a novel and original approach to his work. To do so, we will use the connections that can be established between Menger’s value theory and some consistent philosophical theses by such authors as Ludwig Feuerbach, Arnold Gehlen, and José Ortega y Gasset. We hypothesize that, due to the elements they have in common, these authors will help us delve deeper into the anthropological content of Menger’s basis for the value theory.

We have chosen these authors because we are primarily interested in the aforementioned connection between the value theory and their anthropological–philosophical grounding ideas (and not in other possible connections, such as psychological, sociological, or historical ones), as these authors are recognized for having applied their own philosophical approach to anthropological concerns. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that traditions outside economics have independently adopted perspectives similar to those of Menger. Research often remains confined within a single school of thought, which can limit its broader relevance. Identifying convergence among thinkers from diverse traditions suggests that certain fundamental ideas extend beyond the boundaries of a particular discipline. The recognition of need as the basis for valuation and as a primary motivator of human action is one such idea, present in both Menger and the selected authors, who come from different and complementary traditions, at an anthropological level. This convergence indicates that these concepts are not constructed solely to support a particular economic theory but instead reflect underlying anthropological considerations. Finally, selecting three authors with distinct philosophical approaches and linguistic backgrounds demonstrates that the concept of need as an essential anthropological fact extends beyond specific intellectual traditions. This anthropological fact is prominent throughout the broader philosophical discourse of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Obviously, it is known that Menger was influenced by certain philosophers. His work contains explicit references to Aristotle, Plato, Condillac, and Francis Bacon, and it is also known that he later read Kant attentively, e.g., [

4,

5]. However, the extent to which these authors influenced Menger’s thinking is still a matter of debate, e.g., [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Finally, it is worth noticing the lack of historical connections between Menger and the authors we selected.

Outside of philosophy, it is also known that Menger studied Wundt’s psychology, e.g., [

9] and was later also interested in anthropological topics (e.g., the evolution of institutions, and the production and development of tools), although this latter was mainly recorded in private notes, e.g., [

10].

In what follows, we maintain that Menger, with his value theory, came up not only with a fundamental economic principle, but also with an equally fundamental anthropological one, extending beyond economic theory and dealing with both anthropological and philosophical questions. Campagnolo [

9] also pointed out the anthropological outcomes in Menger’s economic theory, arguing that a “quasi-anthropology” can be found in the

Principles.Finally, we will show to what extent the concept of need, which is at the center of Menger’s value theory, has a heuristic richness that makes it particularly appropriate for creating connective bridges for interdisciplinary research.

2. Menger’s Value Theory

The Austrian jurist and economist Carl Menger (1840–1921) developed in his main work,

Principles of Economics (

Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre, 1871) [

11], what we call a “projective” value theory. This theory made him one of the leading figures in the so-called marginalist revolution in the history of economics, thereby giving rise to the Austrian school of economics.

His value theory is “projective” since, according to it, the value given to objects is the second act of a process, whose first act consists in the valuation of the satisfaction of one’s own needs, and it is this first estimation that is projected onto objects, thus giving them value. Thus, “these values reflect the agent’s perception of capability of these goods to satisfy his needs” [

12]. We call this theory “projective” to highlight this act by the valuers—the act of projecting a value that arises from prior consideration of their own state of need—to emphasize its difference from other ways to conceive value (e.g., as an independent objective property of goods). The notion of projecting presupposes that one must first have that which is projected, then that there is an act of projection, and finally that there is a receptor of what is projected in that act. This places the receptor at the end of a process initiated by the agent. Objectivist theories of value, on the contrary, place the object in the origins of the process (i.e., as a source).

This is how Menger describes this idea: “The value of goods arises from their relationship

to our needs, and is not inherent in the goods themselves. […] Value is thus nothing inherent in goods, no property of them, nor an independent thing existing by itself.

It is a judgment economizing men make about the importance of the goods at their disposal for the maintenance of their lives and well-being. Hence

value does not exist outside the consciousness of men” [

11] (pp. 120–121. Italics added).

The value is thus essentially a relational phenomenon that emerges when the agent is aware of the importance of the goods at his/her disposal for the maintenance of his/her well-being, namely, the satisfaction of his/her needs. Following Valera & Bertolaso [

13] (p. 49), “the value is a relational property (among the subject and the object) and one of the terms of this relationship has necessarily to be ‘somebody,’ i.e., an assessing subject. To summarize, the value is an emergent evaluation of a subjectivity.”

So, the evaluation process is firstly directed to the subject’s own needs [

11]. “Needs”, says Menger, “arise from our drives and the drives are imbedded in our nature. An imperfect satisfaction of needs leads to the stunting of our nature. Failure to satisfy them brings about our destruction. But to satisfy our needs is to live and prosper. Thus the attempt to provide for the satisfaction of our needs is synonymous with the attempt to provide for our lives and well-being. It is the most important of all human endeavors, since it is the prerequisite and foundation of all others” [

11] (p. 77). As “drives imbedded in our nature”, needs manifest themselves as a feeling of a certain uneasiness that the agent experiences or, as Smart points out, “if not [as] a painful feeling, at least, [as] a feeling of incompleteness” [

14] (p. 15). It is only then that consciousness, based on these needs, assesses the goods that can potentially satisfy them and calculates whether there are enough of them to do it or not.

Thus, in Menger’s theory, objects, when encountered by the subject, can acquire new specific meanings. In the process by which objects are transformed into valuable objects, they first acquire the meaning of “useful objects” (

Nützlichkeiten) [

11] (p. 52). This happens when we recognize in them a capacity to satisfy our needs (therefore, a causal relationship). Anyway, this is not enough: these objects become “goods” only when, in addition to this recognition, we can dispose of them voluntarily, to effectively use them to satisfy our needs. If we have no possible access to the useful object, then it cannot be considered a good (e.g., ore from the Moon). Hence, Menger indicates four conditions that must necessarily exist for objects to become goods: (1) there should be a need; (2) the good should satisfy the need; (3) the subject should be aware of this capacity and causal relationship; and (4) the goods must be available [

11] (p. 52). The object has thus gone through three stages: (1) first, as a mere object of the world; (2) then, as a useful object; (3) finally, as a good. The last two are always determined in relation to the subject and his/her needs.

However, the good itself does not yet define whether it has value. Indeed, a final essential relationship is necessary, namely, the relationship of quantities—i.e., the quantity (or intensity) of need in relation to the (available) quantity of the respective good. There are two main quantity relationships: (1) the need (N) is greater than the quantity of goods available (B) (N > B); or (2) the need is less than the quantity of goods available (N < B) [

11] (pp. 94–95). Thus, if B satisfies N, the quantity of goods is greater than what is required to satisfy the need; on the contrary, if the quantity of B is not sufficient, part of N is not satisfied. Menger argues that only in this latter case does the phenomenon of value appears, and B acquires value. On the contrary, if N is covered by B and there is an awareness that it would continue to be covered without the need to perform any specific additional activity (e.g., the case of the air we breathe every day), then B would have no practical interest for us, concerning N: it would have no value for us. Air and similar goods are, to use Smart’s expression, “free gifts of nature” [

14] (p. 17). But as soon as the quantitative relationship changes, from N < B to N > B, that good immediately attracts our interest and acquires value (e.g., on Mount Everest, oxygen is scarce and acquires value) [

11] (pp. 102–103).

It is worth noting that although Menger refers to the problem of value as a “difficult and previously unexplored field of psychology (

Psychologie)” [

11] (p. 28), his theory should not be understood through the lens of the experimental psychology prevalent during his era, which focused on mere responses to stimuli in search of pleasure maximization, nor should it be equated with utilitarian psychology. As Campagnolo [

9] states, referring to the marginalist explanation of the variation in value among different goods, it is “a logical tool and not a moral stand […] about the nature of men”. This perspective applies in general to Menger’s intention, as he considered his theory to be “pure economics”, not empirical [

15] (p. 70). Consequently, the foundational principles of human action are best understood as logically necessary elements intrinsic to the essence (

Wesen) of human action, rather than as psychological or empirical phenomena.

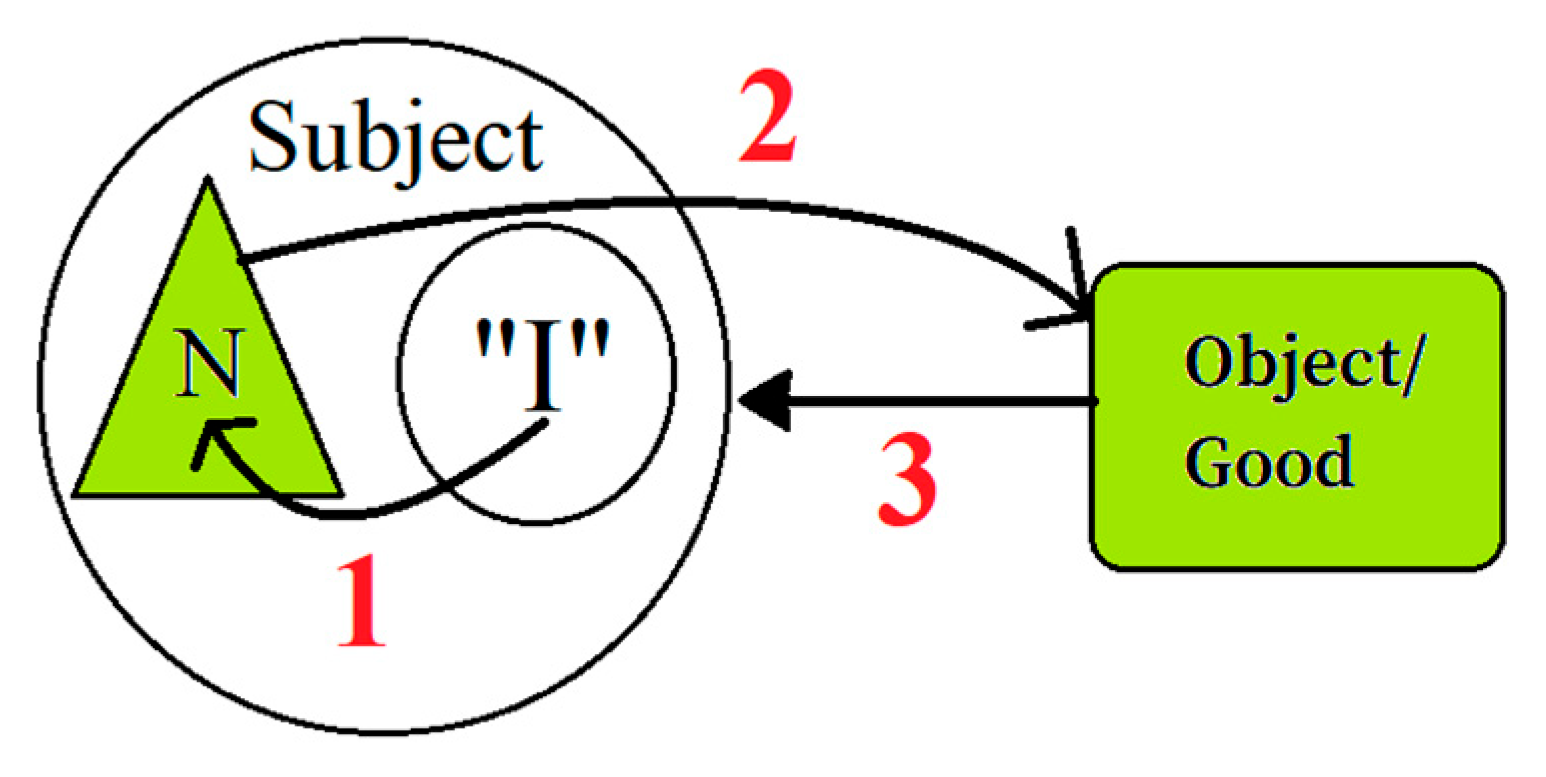

We can schematize (

Figure 1) the process mentioned above as follows:

Once the subject is conscious of the scarcity ratio (N > G), he/she projects the importance that his/her needs have for him/her (i.e., the importance of their possible satisfaction) onto external goods, and thus the latter acquire value and motivate him/her to act.

2 Thus, according to Menger, “value is the importance that individual goods or quantities of goods attain for us because we are conscious of being dependent on command of them for the satisfaction of our needs” [

11] (p. 115).

It should be noted that what we have presented so far is only the core of Menger’s value theory, what Menger called “the nature and ultimate causes of value—that is, […] the factors common to value in all cases” [

11] (p. 121). His complete theory contains more complex developments, including factors as time (i.e., present goods and future goods, value of future goods, production time), the hierarchical–productive relationship of goods (i.e., first order and higher order goods, value of higher goods), risk (which is linked to ignorance or the impossibility of total control of information), the law of diminishing marginal utility, value in economic exchanges, and the transformation of value into prices. However, given that our interest is focused on Menger’s concept of need, an exposition of the core of his theory is sufficient for our purposes.

Now, if need is a constant feature of human life, then it must be part of human action in general. Therefore, as Milford remarks, “to explain […] human behavior, one must start, according to Menger, from the fact that men in general try to satisfy their own needs as completely as possible” [

17], a fact that should be taken as a universal principle of action, fundamentally linked to human evaluations [

18]. In summary, we have a set of closely interrelated phenomena forming the core of Menger’s theory, namely: human needs, the pursuit of satisfaction, scarcity, value, and action. Accordingly, objects are seen through the lens of needs, and that is why they acquire value (when these needs are not met). The subject, the “I”, therefore functions as a kind of mediator that connects objects and needs or, in other words, dissatisfaction and potential satisfiers.

In this way, needs are transformed into the basis of every economic theory, starting from the theory of goods and value. Indeed, it seems clear that Menger gives an essential role to human needs.

3 3. Anthropological Consideration No. 1–Feuerbach and the Dialectical Nature of Needs

Our aim is to elucidate the implicit anthropological constitution of the valuing agent in Menger’s theory. In his view, as we pointed out, the agent is fundamentally a “needy” being, namely, a being with constant needs. This is not an accidental element but an essential feature, a part of the very constitution of the human being as such. Thus, human action (including economic action) is primarily motivated by a need as a vital force, as an impulse born out of the very condition of human life. Indeed, the “

conatus”

4 that can effectively push the human agent to develop an action has this negative character, of lack, of urgency, of uneasiness.

Certainly, the philosopher who, probably more than any other, emphasized the negative nature of human needs was Ludwig Feuerbach [

25]. Indeed, in his essay

On Spiritualism and Materialism, Especially in Relation to the Freedom of the Will [

26], he developed a theory of needs with dialectical elements in it, which implies a constant dynamic of opposition between their negative nature and the positive goal to which they aim. If Menger envisioned the general relationship between needs, value, and action, we could say that Feuerbach delved into the concrete logic of this relationship.

As pointed out by many interpreters [

27,

28,

29], the concept of sensation (

Sinnlichkeit, Empfindung) is the key element in Feuerbach’s later ethical theory since for him it is on this faculty that will and agency are based. As Gooch states, “Feuerbach regards sensation as the ‘first condition of willing’ since without sensation there is no pain or need or sense of lack against which for the will to strive to assert itself” [

29], for “if there is no sensation, there is a complete absence of everything else” [

28].

Thus, in Feuerbach’s view, the negative state in which the need necessarily manifests itself presupposes its opposite, for it consists of nothing else but wanting to transform itself into a positive state. In this sense, a need is not exclusively a negative state, but a state that has already in its negative aspect a tension with a direction: to its opposite, to a state of satisfaction, which Feuerbach calls, in general, a state of happiness [

26] (pp. 108 ff.). If a need should be interpreted as a force with direction, it is like a vector (i.e.,

). Feuerbach argues: “Hunger, due to a previous abstention or deprivation of food, holds me in its power; it forces me to think only about my stomach. But if hunger is appeased and thus becomes a thing of the past, then I now have time and freedom to think about my head instead of my stomach:

primum vivere deinde philosophari (first live and then think or philosophize) […] [In this way], every present tense of the will [i.e., ‘I want x’] presupposes a perfect tense of its opposite or of an another in general [−x]. I want to work or move, after and because I rested; I want to rest, after and because I have worked or moved, that is, because I have not rested. Without this Not of the past [

vorhergegangenes Nicht] I have no foundation, motive or impulse for wanting” [

26] (p. 103).

I want A because I have not had A, that is, I have been living with -A, and this is a fundamental part of the reason why I want A now. The reason for wanting water is, therefore, having lived for too long without water. It is not, then, a simple (static) absence but rather a dynamic one, which must be effectively manifested in the agent to reach the point of a real motivation for his/her action. Indeed, -A emerges in our experiences as a real fact through and thanks to sensitive/affective perception, namely, to feeling:

“The first condition of will is, therefore, sensation (

Empfindung). Where there is no sensation, there is no pain, no suffering, no uneasiness, no deprivation (

Noth), there is no lack, no need (

Bedürfniss), there is no hunger or thirst; in short, there is no unhappiness, there is no evil (

Übel). But where there is no evil, there is no impulse of opposition […] there is no impulse and effort to defend oneself against evil, there is no will. Rejection (

Wider-wille) […] is the first will” (

Der Eudämonismus, [

26] (p. 231)). Lack, uneasiness, and pain are not abstractions, but real phenomena because we feel them, and as such, they are part of a dynamic of balances and imbalances of opposites at a psychological–affective level [

30].

Through sensitive/affective perception we experience, therefore, a dynamic of tensions and distensions perceived as negative and positive co-determinant feelings, which are at the origin of what in practical life is considered, in a broad sense, as “costs” and “benefits”. The ultimate source of the phenomena of costs and benefits, which explain the action, is to be found in these sensitive/affective experiences because these are responsible for the perception of certain situations as negative and others as positive. Affective experiences are the sensorium through which the mind perceives the surrounding world as painted with a wide palette of shades that carry the positive or negative sign (and its nuances or degrees) or—to use another analogy—the sensorium through which the mind perceives the world as an axiological topography with its value valleys and value peaks of different heights.

So, as sensible beings, we perceive the world in terms of positive and negative, as “good” and “bad”: we have an axiological perception at the base of which are our needs wanting to transform themselves, through the will, into a positive state called satisfaction. The search for the satisfaction of needs is what we call purpose. So, the concept of need is tied to perception, purpose, and action. All of which is aligned with Menger’s theory.

In Feuerbach’s view, the will is an impulse (“where there is no impulse [

Trieb] there is no will” [

26] (p. 108)): it is not something abstract but always embodied. That is why the

ich will (I want) does not exist and cannot exist on its own, as if it were an absolute principle (as, for instance, German idealism in general conceived it). “In short —says Feuerbach—, the will is found under all the conditions and forms of finitude and temporality. With the

I want is inseparably linked the question

what? A will separated from the matter of the will is an absurdity” [

26] (pp. 110–1). Indeed, there is no pure abstract will separate from the concrete sensibility of the individual: “Without sensation, there can be no will” [

28]. Thus, the will operates as an intermediary between the feeling of lack and the desire for satisfaction, on the one hand, and that which can satisfy it, on the other. Therefore, it is fundamentally a relative (and not an absolute) phenomenon, as the thirst that the body suffers is relative to the water that the world offers.

This will, as a general impulse, is essentially correlated to “happiness” (in its broadest sense, happiness means satisfaction and vice versa), from which it follows that “where there is no impulse to happiness [

Glückseligkeitstrieb], there is no impulse of any kind. The impulse to happiness is the impulse of impulses” [

26] (p. 108). So, we have a hierarchy of impulses and purposes, where the impulse to happiness is the highest one, and it is always presupposed in every other: “But then what do I want?—asks Feuerbach—Nothing else than the end of what causes me aversion [

Widerwilligkeit], the end of an evil [

eines Übels] —where there is no evil, there is no will—the end of suffering [

eines Leidens]—to want means

not to want to suffer. In short, I want nothing else but the non-being of my non-being” [

26] (p. 111).

In this sense, suffering has a teleological meaning

per se since it reveals the desire not to suffer: “The hell of nature […] is the enemy of torment insofar as this is the enemy of mankind: it wants to end, it wants its opposite, it wants the kingdom of heaven; for thirst itself is only the will to drink and not to suffer thirst [

nicht zu dursten]” [

26] (p. 123).

It should be noted that one cannot speak of negative feelings without presupposing the impulse to turn them into positive ones. These terms are mutually implicated. Therefore, we have a set of elements forming a structural unit. For Feuerbach, this structure is present “in everything that lives and loves (

lebt und liebt), that is and that wants to be” [

26] (pp. 230–231), that is to say, in every living being. In this sense, the impulse toward happiness (

Glückseligkeitstrieb) would have biological, psychological, and anthropological connotations in Feuerbach. One might then ask whether there is something similar in Menger’s notion of the pursuit of satisfaction of needs (

Bedürfnisbefriedigung), namely, an extension of his principle to the entire realm of living beings. Menger, however, rejected a psychological interpretation of his theory [

9], as he saw it as “pure theory” and “a priori” [

4,

31], which does not mean that he denied the role of the senses, but it calls for caution with this type of comparison. In any case, both authors saw in the same core of ideas a general structure that cannot be left out when analyzing human action. In Feuerbach, this structure is concrete; in Menger, it has a more formal meaning. The relation between form and matter, in this case, is one of the anthropological problems that arise from this comparison.

5 From what has been said so far, it should be clear, though, that in Feuerbach the concept of need is, as in Menger, the center of the theory of action. However, unlike Menger, Feuerbach offers a description of the

content of this phenomenon through the dynamism of affective opposites, of positive and negative feelings. Need is then defined as a negative psychic state, and this negativity analytically implies a tension, proper to the act of wanting, which points towards its opposite: a positive state we call satisfaction. Therefore, in the very experience of wanting, we should find a teleological direction: the desire to cease to be a need to become a satisfaction.

We maintain that what appears explicitly and is extensively developed in Feuerbach are implicit elements in Menger’s theory.

6 We also find in Menger, as Campagnolo points out [

9], “a rigorous theory of subjective well-being and happiness”. Menger’s theory is grounded in the principle of need satisfaction (

Bedürfnisbefriedigung), which he identifies as the primary motivator of human action. According to Menger, the value of objects is determined by the significance that individual needs and their fulfillment hold for each person. He further asserts that, by natural instinct [

11] (p. 77), individuals primarily seek to preserve their lives and well-being. This perspective constitutes the core anthropological characterization of the Mengerian agent. While Feuerbach concurs with this view, he extends the analysis by critically examining the condition of being finite, sentient beings with needs that require satisfaction.

4. Anthropological Consideration No. 2–Gehlen and the Human Being as a Defective Being

Arnold Gehlen’s philosophical anthropology is also based on the concept of need. Based on it, he explains both the peculiar nature of human beings from a zoological and morphological point of view [

32] and the origin of culture as the proper habitat for human life [

33].

To introduce Gehlen’s standpoint, we can retake Menger’s value theory starting from the production process and the necessary use of goods of higher orders in it. Menger argues: “In cases in which our requirements [needs] are not met or are only incompletely met by goods of first order […] we turn to the corresponding goods of the next higher order in our efforts to satisfy our needs as completely as possible, and attribute the value that we attributed to goods of first order in turn to goods of second, third, and still higher orders whenever these goods of higher order have economic character” [

11] (p. 151).

The satisfaction of needs requires goods that can fulfill them. Menger calls those goods that produce immediate satisfaction first-order goods [

11] (p. 56). If we take food as an example, we can find first-order food goods that are not produced by human beings, namely, natural goods. However, the fact of the emergence of production as a human activity implies that, at some point, natural goods did not satisfy all human needs and, therefore, that human beings found it necessary to create those goods they needed and could not find in nature.

The impulse leading human beings to leave the natural world and become “technical” is linked to the experience of their needs: needs push human beings to go “beyond” animal life [

34,

35]. Indeed, from an anthropological point of view, human beings are not satisfied with “a natural life” as other animals are, but rather, they feel the need to transform the natural world into a human world, to transform the natural environment into a

cultural environment. The human being is, in short, “irreducible to the animality” [

35] (p. 48). Fischer [

32] (p. 167) explains this point as follows: “In the hiatus of the living circle of functions they identify a completely new living space for encounter and challenge. This space can be referred to, and reconstructed as, the human sphere.” Drawing on Herder’s intuitions, Gehlen’s theory is based on the idea that the human being is fundamentally a “deficient being” (

Mängelwesen) [

33] (pp. 27ff.), that is to say, an animal exceptionally lacking the physiological tools to survive in the natural world, from which it follows that the need for technology can already be found inscribed in its own deficient body [

18]: either he/she becomes a technical being or dies due to the lack of natural physiological adaptation.

7The relationship between the animal and its environment is organically structured due to the morphological adaptation of the animal to the environment: “Organic structure and environment are mutually presupposed concepts” [

33] (p. 27). For this reason, the animal properly has an environment: it has a specific place in the natural world where it can deploy its equally natural life.

8 This symbiosis between the organism and the environment cannot be applied to human beings: they do not have a natural habitat they were specially adapted to. Their lack of a natural environment is correlated to their “structural” (and not only quantitative) [

36] (p. 374) deficiency of the physiological means of adaptation (they have no fur to live outdoors, no claws or fangs to defend themselves and hunt, their maturation process and their period of dependence are exceptionally long, etc.).

9 They lack an environment since they lack adaptation to any environment [

37] (p. 181).

So, the thesis of the deficient being is based on the implicit idea of need being a fundamental determinant of the biological and cultural life of human beings. Lack and deficiency are different words for need.

The consequence of this human unfitness, this lack of a specific habitat, and these deficient natural means for natural life is the emergence of a

pressure10 originated from human biology, which pushes human beings to

create a new world11: since they have no place in nature, they

have to produce their own habitat. “All deficiencies in the human constitution, which under natural conditions would constitute grave handicaps to survival, become for man, through his own initiative and action, the very means of his survival; this is the foundation for man’s character as an acting being and for his unique place in the world” [

33] (p. 28). Indeed, human beings are “plastic” living beings [

37] (p. 374), since they cannot adapt themselves to the environment. This last is, therefore, fundamentally non-natural or

artificial. This is what we call “culture.” Thus, the original biological deficiency generates the need to create culture as the last option for human survival [

39]. In other words, “lacking the natural endowment that would assure survival, he must equip himself with tools and weapons such as only conscious intelligence could devise” [

36] (p. 184).

Given that the human being does not have a specific environment and specialized natural adaptation, he/she has a fundamentally “indeterminate” character [

33] (p. 27) and, therefore, one of “world-openness” [

33]. Not being restricted to a specific part of the world, he is potentially open to the whole world. According to Gehlen, a fundamental task for the human being is self-determination, making the individual a challenge to himself [

33] (p. 28). This challenge involves constructing a personal world necessary for survival, which entails problems that must be confronted and resolved “through his own efforts” [

33] (p. 28). An important part of these problems is that, being a world-open being, “he is flooded with stimulation, with an abundance of impressions, which he somehow must learn to cope with. He cannot rely upon instincts for understanding his environment. He is confronted with a ‘world’ that is surprising and unpredictable in its structure and that must be worked through with care and foresight, must be experienced. By relying on his own means and efforts, man must find relief from the burden of overwhelming stimulation; he must transform his deficiencies into opportunities for survival” [

33] (p. 28).

From this perspective, it could be argued that the phenomenon of production referred to by Menger (i.e., an action taken with the deliberate purpose of producing that which nature cannot provide on its own) arises as a result of the peculiar character of human needs, which are not restricted to the purely natural world but point already to the production of the cultural world. The ancestral technologies (e.g., the tools, the bow and arrow, the ornaments, the first constructions) are the primordial manifestations of the “non-natural” needs of human beings. Gehlen speaks of a “surplus” in human impulses or an “excess of drives” (

Triebüberschuss) [

33] (pp. 49ff.) that cannot be satisfied in nature.

12 In short, the existence of production implies that the human being is organically deficient; to compensate for this structural deficiency, being full of drives, he/she is compelled to leave aside nature and create culture.

13 Through his deliberate action, “man actively masters the world around him by transforming it to serve his purposes […]. Culture is therefore the ‘second nature’—man’s reconstructed nature, within which he can survive. ‘Unnatural’ culture is the product of a unique being, itself of an ‘unnatural’ construction in comparison to animals” [

33] (p. 29).

Furthermore, as cultural beings, human beings are constrained to project themselves into the “invisible” to satisfy their needs. Humans are “Promethean” beings, projecting themselves fully into the invisible future and capable of discovering hidden relationships around them (e.g., causal connections between distant phenomena, such as the creation of clouds from the evaporation of seawater or the death of a dam from the observation of the driving force capacity of a taut rope) [

33].

In short, the need presses human beings to develop all the features that will allow them to produce culture (through the production of cultural objects), namely, the consciousness of the future; the projection of their evaluations to future times; imagination and representation; the conceptual grasping of things and events; the capacity to discover non-immediate causal connections; the distancing and abstention from immediate life (due to the processes of production). All these aspects suppose a particular type of consciousness, different from the animal one [

35]. With this set of ideas by Gehlen, we can see that the principle on which Menger’s projective value theory is based (a subjective value theory anchored in the system of needs) not only explains economic actions, but is also at the heart of fundamental anthropological questions such as those relating to the distinction between humans and animals, the departure from purely natural life, and the creation and development of culture, at the core of which lies the process of production.

Human beings produce their cultural (or human) world in the midst of nature mainly by means of technology [

41]. To properly understand the relationship between needs and technology, we will refer to Ortega y Gasset’s standpoint.

5. Anthropological Consideration No. 3–Ortega y Gasset and the Human Liberation Through Technology14

Ortega y Gasset’s philosophical anthropology can help us to extend Gehlen’s physiological approach to the human being to a psychological one: according to him, human beings are not only incomplete in a zoological-physiological sense, but also in a psychological or “spiritual” one. They appear as lacking (and therefore in need of) both their own world (as they have no natural given world) and their own inner selves. These are a task to do or accomplish and, thus, a

problem to solve. Even Gehlen highlights this point when he remarks that “man would be […] not only a being who must […] seek explanations, but also, in a certain sense, would be unequipped to do so. In other words, man is a being whose very existence poses problems for which no ready solutions are provided” [

33] (p. 4).

15According to Ortega, this constant problem of not having a ready-made world and an already-defined personality should be solved, first, through productive activity, which only exists thanks to technology [

42]. This last is “the reform that man imposes on nature in order to satisfy his needs” [

43] (p. 21). In this sense, technology cannot be simplistically identified with “means” or “instruments”: rather, it is “a general term for man’s self-creative action” [

44] (p. 20). Technology is, then, a powerful reaction to the needs (i.e., environment) imposed on human beings by nature [

45].

Through technology, human beings transform their environment by adapting it to their needs (“

necesidades”) and producing the means for their survival. This production, by taking time, implies a suspension of the use of the good in question (until it is finished and available) and, therefore, a detachment or separation from its immediacy: since human products are not already given in the world, humans have to separate themselves from their immediacy and put their lives on hold, so to speak, to be able to produce them. Regarding this point, it is worth quoting the following passage from Ortega y Gasset: “The animal, when it cannot exercise an activity of its elementary repertoire to satisfy a need […] lets itself die. Man,

16 on the other hand, triggers a new type of doing that consists in producing what was not there in nature, either what is not there at all, or what is not there when it is needed […]. Thus, he makes fire when there is no fire, he makes a cave, that is to say, a building, when it does not exist in the landscape […]. Now, note that making fire is a very different activity from warm oneself up, that cultivating a field is a very different activity from feeding oneself” [

45] (p. 18).

This “second line of activities” [

43] (p. 17) implies the existence of production goods of higher orders, which in turn presupposes the human need to go

beyond the limits of the immediate natural world and, in this sense, to break the magic circle of the purely natural: production accounts for the technical (“artificial”) nature of human beings [

46]

17. This is what Ortega y Gasset refers to when he says: “Heating, agriculture and the manufacture of cars or automobiles are not, then, acts in which we satisfy our needs, but rather, on the contrary, they imply a suspension of that primitive repertoire of acts in which we directly seek to satisfy them. Ultimately, this second repertoire is aimed at this same satisfaction and nothing else, but—and there it is!—it presupposes a capacity that is precisely what the animal lacks. It is not so much intelligence […] as the ability to detach oneself temporarily from these vital urgencies, to detach oneself from them and be free to occupy oneself with activities that, in themselves, are not the satisfaction of needs” [

43] (p. 18).

The immediate world and purely biological life do not satisfy human life. This non-satisfaction goes hand in hand with its detachment from biological life [

48]. That is why the productive detachment of humans is different from the animal one. Human beings, argues Ortega y Gasset [

43] (p. 20), distance themselves from their basic needs because their sense of life, together with their condition of deficiency, pushes them beyond them. They try to satisfy their basic needs to go beyond them to dedicate themselves to other tasks: “While all the other beings coincide with their objective conditions—with nature or circumstance—man does not coincide with it, he is something foreign and distinct from his circumstance” [

43] (p. 20). The animal seems to be absorbed by biological needs. Its activity stops once it has satisfied them: “The animal cannot withdraw from its repertoire of natural acts, from nature, because it is nothing but nature and would have, by distancing itself from it, nowhere to put itself” [

43] (p. 20).

Therefore, technology and production allow human beings to free themselves from their natural needs to devote themselves to these other purposes. These purposes are not properly natural and, for this reason, the “system of needs” of the human being is constituted by the double dimension of the natural and the unnatural, and this shows that human life itself has this quality of being both natural and unnatural. Indeed, Ortega y Gasset says [

43] (p. 41): “Apparently, man’s being has the strange condition that in part it is akin to nature, but in another part it is not, that it is at once natural and super-natural —a kind of ontological centaur— that half of it is immersed, of course, in nature, but the other part transcends it.”

Ortega further adds that this ontological centaur, due to the special characteristics of his/her system of needs, is not satisfied with merely “being” in the world but seeks his/her satisfaction rather in “well-being.” “Man’s endeavor to live,” argues Ortega y Gasset, “to be in the world, is inseparable from his being well. Even more: that life means for him not simply being, but well-being, and that he only feels as a need the objective conditions of being, because this, in turn, is a presupposition of well-being” [

43] (p. 26). From this idea, Ortega y Gasset infers the following principle: “Well-being and not being is the fundamental need for humans, the need of needs” [

43] (p. 26), hence in reality, “man does not make any effort to only be in the world. What he does strive for is to be well. Only this seems necessary to him and everything else is a necessity only to the extent that it makes well-being possible” [

43] (p. 27). The mere being, the mere “survival”, is not unconditional in human beings; it is only a necessary condition

for their well-being.

This idea basically follows Feuerbach’s argument, for whom “where there is no impulse to happiness, there is no impulse of any kind. The impulse to happiness is the impulse of impulses” [

26] (p. 108).

For Ortega, human life is always a problem to be solved: for this reason, we find ourselves constantly having to make decisions (big or small). Thus, human life is not completely given beforehand: everyone must create his/her own life. Indeed, one of Ortega’s main theses is that the human being does not have a nature: he/she has a history (e.g., [

46,

49]). In this regard, human beings dwell on the world in a projective way, determined by the future tense: we constantly seek our satisfaction, well-being, or happiness in that absent, hidden, or even non-existent life. For this reason, the human being “has ‘technology’ before he has ‘a technology’” [

44] (p. 21). On this topic, Ortega y Gasset says: “Life is given to us—or rather it is thrown to us, or we are thrown into it —, but that which is given to us, life, is a problem that we need to solve ourselves […]. In the same way that our existence is at every moment a problem, big or small, that we have to solve without being able to transfer the solution to another being, it means that it is never a solved problem […]. Isn’t this surprising? […] our life is our being. We are whatever our life is and nothing else; but that being is not predetermined, resolved beforehand but we need to decide it ourselves, we need to decide what we are going to be, for example, what we are going to do when we leave this room” [

50] (pp. 50–51).

The being of human life consists, then, in being what it is not yet: “[the human being] is a being that consists more than in what he is, in what he is going to be, therefore in what he is not yet” [

50] (p. 53). This indicates to what extent, as human beings, we are in constant restlessness, movement towards the future, asymptotic searching and hunting, so to speak; in short, it shows the

problem we are to ourselves. In this regard, the most relevant human feature is imagination and not action: “Ortega thinks the traditional relation between imagination and action has been reversed” [

44] (p. 21). The relation between

póiesis and

nóesis should definitively be revised, as the same Ortega y Gasset [

43] (p. 29) shows, referring to the Gospel episode of Martha and Mary.

In short, in Ortega, the concept of need is again a fundamental principle that enables us to deduce the main features of the human being and his/her actions in the world. For which, as homo faber, humanity has developed technology, fabrication, and production and, with them, the capacity to make future projects. In this sense, the human being itself is projected as a task to be realized.