Abstract

(1) Background: Settler colonialism has severely disrupted Indigenous ancestral ways of healing and being, contributing to an onslaught of health disparities. In particular, the United Houma Nation (UHN) has faced large land loss and trauma, dispossession, and marginalization. Given the paucity of research addressing health for Indigenous individuals living in Louisiana, this study sought to co-identify a United Houma Nation health framework, by co-developing a community land-based healing approach in order to inform future community-based health prevention programs. (2) Methods: This pilot tested, co-designed and implemented a land-based healing pilot study among Houma women utilizing a health promotion leadership approach and utilized semi-structured interviews among 20 UHN women to identify a UHN health framework to guide future results. (3) Results: The findings indicated that RTOR was a feasible pilot project. The initial themes were (1.) place, (2.) environmental/land trauma, (3.) ancestors, (4.) spirituality/mindfulness, (5.) cultural continuity, and (6.) environment and health. The reconnection to land was deemed feasible and seen as central to renewing relationships with ancestors (aihalia asanochi taha), others, and body. This mindful, re-engagement with the land contributed to subthemes of developing stronger tribal identities, recreating ceremonies, and increased cultural continuity, and transforming narratives of trauma into hope and resilience. Based on these findings a Houma Health (Uma Hochokma) Framework was developed and presented. (4) Conclusions: Overall, this study found that land can serve as a feasible therapeutic site for healing through reconnecting Houma tribal citizens to both ancestral knowledges and stories of resilience, as well as viewing self as part of a larger collective. These findings also imply that revisiting historically traumatic places encouraged renewed commitment to cultural continuity and health behaviors—particularly when these places are approached relationally, with ceremony, and traumatic events tied to these places, including climate change and environmental/land trauma, are acknowledged along with the love the ancestors held for future generations.

1. Introduction

By systematically removing Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands, connections to ancestral wisdom and the transmission of Indigenous cultural protective factors have been severely disrupted (Baskin 2016; Billiot et al. 2019; Jennings et al. 2020; Walters et al. 2011). This settler colonialism has been described as a systematic imperial act of taking territory by force in distant lands and replacing the population with new settlers (Wolfe 2006). Throughout US history, settler colonialism has structurally sought to erase Indigenous people through genocidal (e.g., Indian Removals), ethnocidal (systematic destruction of lifeways; e.g., Boarding Schools), and/or epistemicidal (systematic destruction of thought ways/languages; e.g., outlawing Indian spiritual or cultural practices) policies and practices. These methods have been used to displace or dispossess Indigenous people from their traditional homelands, lifeways, and identities (Walters et al. 2018); and the effects have reverberated throughout subsequent generations. As such, settler colonialism has been identified as a key social determinant of health for Indigenous peoples and should be considered in health intervention designs (Czyzewski 2011; MacDonald and Steenbeek 2015).

Research further indicates that settler colonialism, combined with historically traumatic events, has fueled historical trauma responses and corresponding health disparities such Diabetes Type II, substance use/addictions, cancers, and cardiovascular diseases among Indigenous individuals (Dobson and Brazzoni 2016; Schell and Gallo 2012; Wang and Beydoun 2018). Some empirical findings indicate that after controlling for contemporary trauma—including childhood physical and sexual abuse, as well as adult military combat exposure—historically traumatic land-based events (e.g., forced relocation, loss of land, land desecration) can continue to have a significant effect on contemporary mental and physical health among Indigenous Two Spirit populations (Walters et al. 2011). By interrupting connection to land and related Indigenous knowledges, settler colonial land trauma has especially disrupted Indigenous peoples’ ability to continue their language, relationships with the land, and spirituality related to place (Baskin 2016; Brown et al. 2012). Moreover, these disruptions of intergenerational knowledge transfer inhibit a people’s ability to fulfill their Original Instructions (ancient teachings) and responsibilities—thus impacting wellbeing. Original Instructions are tied to land and cosmos and require a relationship between person and place with specific obligations and responsibilities, as described by Tewa scholar, Gregory Cajete (1999). Through attempting to sever Indigenous collective identities and disrupt their views of self as connected to the land, settler colonial policies sought to extinguish Indigenous cultures (Watts 2013). This systematic disruption to Indigenous land, place, and healing has further exacerbated current environmental stressors; e.g., food deserts; environmental distress, land loss, and systematic marginalization/discrimination (Billiot 2017; Brown et al. 2012; Holm et al. 2010).

Despite enduring settler colonialism and historically traumatic events, many Indigenous commmunities have maintained their teachings and connections related to the land. The complexity of living within settler colonialism demands that we not only “recognize the persistence of Indigenous peoples over 500 years of colonization, but the survivance (Vizenor 2008) of Indigenous peoples in holding on to deep cultural threads of knowledge and practices that endure to this day” (Walters et al. 2018). This land-health connectedness is also reflected by an aboriginal scholar (Burgess et al. 2005, p. 120) who notes:

“Our identity as human being remains tied to our land, to our cultural practices, our systems of authority and control, our intellectual traditions, our concepts of spirituality, and to our systems of resource ownership and exchange. Destroy this relationship and you damage sometimes irrevocably—individual human beings and their health.”

Moreover, as these threads of knowledge are engaged and ancient teachings (aka Original Instructions) are revitalized and regenerated in Indigenous community practices, Indigenous thrivance is activated, and Indigenous community wellbeing is actuated. It is from this thrivance perspective that we contextualize the present land-based healing study development, methods, and findings.

1.1. UHN Returning to Our Roots Background and Health as Related to Lands

The United Houma Nation is one of the three largest state-recognized tribes, who do not have access to federal Indian Healthcare Service to help address health disparities or federally entrusted reservation lands (Billiot and Parfait 2019). Given high rates of historical traumatic event exposures (e.g., environmental contaminants, forced relocations), oppression, and lack of resources, the UHN currently suffers from diabetes rates as high as 24% of their population (UHN 2015), a rate similar to other Indigenous groups. Meanwhile, White settler populations maintain diabetes rates around 8% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/CDC 2020). Furthermore, 53% of the UHN population experience cardiovascular disease (UHN 2015) as compared to 8.6% of Indigenous peoples in general and 5.8% of the US white population (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/CDC 2020). These Indigenous health disparities have been attributed to stressors related to historical i.e., colonization, genocidal, and ethnocide attacks, and current traumas i.e., experienced violence, racial discrimination, and land trauma (IHS 2013; Johnson-Jennings et al. 2014; Sotero 2006; Walters et al. 2018). While western health interventions have not been as effective as hoped for Indigenous groups, especially in terms of diabetes, obesity, and chronic disease (Adams et al. 2008; Satterfield et al. 2016), community-engaged approaches show promise and have been deemed critical for Indigenous communities in their ability to self-govern their health, or exercise health sovereignty (Jennings et al. 2019; Johnson-Jennings et al. 2019, 2020b). Indigenous grassroots efforts; arising from and, or in collaborative partnership with communities, have begun to effectively address obesity food challenges and often center around reconnecting with land and increasing traditional foods, or Indigenous foods historically linked to Indigenous communities (Johnson-Jennings et al. 2020a; Satterfield et al. 2016). In particular, Indigenous groups’ reconnection to land may be key in addressing obesity and other chronic health diseases. Given the paucity of research addressing health for Indigenous individuals living in Louisiana, this study sought to co-identify a United Houma Nation health framework, drawing from a land-based healing approach in order to inform future community-based chronic disease prevention programs.For the Houma, as for all indigenous people, existence is about people and place. our ties to each other and our ties to the land are part of the dynamics of our identity and culture.(Dardar 2008, p. 33)

In planning this study, the authors in collaboration with the United Houma Nation determined that land and environmental factors are critically important to the culture, health, and wellbeing of the United Houma Nation/UHN. UHN Tribal citizens, commonly referenced as Houma, reside in interwoven bayous and canals within six distinct parishes (i.e., Terrebonne, Lafourche, Jefferson, St. Mary, St. Bernard, and Plaquemines) along the southeastern coast of Louisiana, which encompasses 4570 square miles (UHN 2015). At contact, ancestors of UHN lived on the most fertile ground of what became the Louisiana Territory. Settler colonial land laws of the French, Spanish, and U.S. subsequently displaced UHN ancestors further and further down the Mississippi River until arriving at the present-day location along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. It is on the bayous of the Mississippi that UHN thrived and built relationships with the land and water. Although the coastal Houma territories are geographical food deserts, UHN has been able to communally provide for tribal citizens through subsistence activities such as fishing and hunting, which have minimized food insecurities. Recently, human activities causing highly contaminated waters and coastal erosion drastically decreased acreage for gardening, leading many UHN tribal citizens to rely upon commodity food distributions and woefully inadequate grocery stores, instead of a diet rich in fresh, protein-packed seafood (Billiot and Parfait 2019). For instance, UHN has endured land trauma via oil rig drilling, dam construction, and dredging swamplands, which have contaminated their seafood and environment. Between 2010 and 2015, 35% of all UHN citizens reported that they continue to be negatively affected, especially in terms of health and wellbeing, by the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill (UHN 2015). UHN has further experienced large-scale land dispossessions from global environmental changes (Billiot 2017). They, subsequently, have significantly less land in which to farm, garden, hunt, and, overall, feed themselves. UHN citizens have reported moving from working outdoors daily and consuming diets rich in fresh seafood and vegetables, towards the poor eating habits of many Americans—including the increased consumption of processed foods and sedentary employment. All of which are having devastating health effects among many Indigenous groups (Jennings et al. 2019). By enduring such land trauma and inability to access and engage in ancestral practices, UHN’s relationships with land and ancestors have been limited. They have also been unable to continue passing such practices onto future generations; or in other words, they are unable to maintain their cultural continuity (Champagne 2007). This inability for Indigenous nations to continue their culture has been found to negatively impact tribal citizens’ physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health (Gracey and King 2009; King et al. 2009). Thus, it is unsurprising, that UHN has high rates of both diabetes and heart disease, even higher than other Indigenous groups (UHN 2015). These disparate rates, originally, initiated UHN to identify their views of health as related to the land and to determine if the land would serve as an appropriate context for healing.

1.2. Houma Reconnecting with the Land for Cultural Continuity and Healing

For Indigenous peoples, land dispossession has a significant effect on the ability to maintain cultural continuity (Champagne 2007; Chandler and Lalonde 2016; Oster et al. 2014; Parlee et al. 2005). The UHN has experienced large land dispossessions, which has isolated communities, and hampered their ability to fluidly transmit land-based teachings (Billiot et al. 2019). Hence, the UHN leadership, elders, and key stakeholders proposed that reconnecting to the land needs to be considered in order to increase cultural knowledges around health. Other Indigenous groups who have re-established relationships to ceremonial spaces and the wisdom of their ancestors have also improved or see the potential to improve health (Agans et al. 2014; Carroll et al. 2018; Dobson and Brazzoni 2016)). Indigenous ancestral wise practices differ from western best practices in that they elevate ancestral and Indigenous ecological knowledges and may hold more promise than western approaches for improving health (Johnson-Jennings et al. 2020a). In addition, the UHN leadership also voiced that Indigenous knowledges need to be learned through the direct, lived experiences on the land. As noted by other researchers (e.g., Jennings and Lowe 2014; Dobson and Brazzoni 2016; Radu et al. 2014; Roue 2006), learning from the land includes fostering interconnectedness between individuals and their environment or landscape, with this relationship being primary to healing. Therefore, re-establishing land connections and relationships through place-based learning opportunities may be appropriate and necessary to improving Indigenous health (Anderson et al. 2011; Dobson and Brazzoni 2016).

1.3. Land as an Appropriate Healing Context for Houma

For many Indigenous communities, land remains a central location, or place, for healing and a culturally appropriate context to conduct health interventions (Brown et al. 2012; Luig et al. 2011; Walters et al. 2018). The interdependency among humans and nature, the physical and spiritual worlds, the ancestors (past, present, and future), and all living beings (animate and inanimate) are bound to one another in what Cajete (1999) refers to as a sacred ecology—an interconnectedness deeply reflecting spirituality and cultural cosmology tied to place. The field of geography has often discussed humans and land in terms of place, described as the human attachment of meaning to a physical space or location (Kearns and Moon 2002). This western, unidirectional lens perceives place as being contrived within the minds of the human who consciously decide, or change, the meaning as based on both emotions and experiences—including positive and negative/traumatic connections, as well as socio-political constructs (Manzo 2005). More recently a westernized, relational view to place and health has been proposed, which includes viewing factors such as environmental hazards, or lack of access to supports, or healthcare, and a reciprocal influence of place on individual’s health (Cummins et al. 2007). Yet, Johnson-Jennings et al. (2020b) found that Indigenous peoples hold more than a unidirectional relational view of the land; instead viewing an interrelationship with the land who is an animate, living entity- a mother.

Given this familial relationship, Indigenous individuals consider the land as co-contributing to their meaning of place and influencing their healing journey. Land then serves as an active agent in healing, provides a culturally appropriate location to conduct a healing, and supports the common factors of healing found in most health interventions around the world (Johnson-Jennings et al. 2020b). Even more, Indigenous land-based initiatives are entrenched within community knowledge, guided by community elders and knowledge keepers, and often arise from the community as grassroots initiatives, sometimes in partnership with Indigenous and allied scientists (see Billiot 2017; Jennings et al. 2019; Jennings et al. 2020; Jennings and Lowe 2014; Walters et al. 2011; Walters et al. 2018). Thus, engaging upon the land can serve as a potentially effective and sustainable approach to health. The UHN leadership and researchers agreed that a land-based health intervention could illuminate how tribal citizens perceive health and wellbeing.

1.4. Indigenous Land-Based Healing as a Potential Houma Framework

UHN leadership selected the land as the healing setting and guiding framework for their proposed intervention. Given there remains no clear definition, the authors consider Indigenous Land-based healing as [re]connecting to the land and centring the land in order to conduct healing or health interventions. Land-based healing differs from western health interventions in that an immediate healing is not expected. Instead, Indigenous healing beliefs have been described as a longer-term process, an unfolding or journey, that one must undertake, especially upon the land (Johnson-Jennings et al. 2020a; Karanja 2020). Therefore, a land-based healing setting serves as the catalyst for transformation towards wellbeing and health, which will occur over time. Land-based healing has been seen to encourage redeveloping relationships with the land, the environment, and with other humans. Furthermore individuals reconnect to the place of their ancestors, their original instructions, or teachings. They also contextualize their selves as being future ancestors who are responsible for the future generations (Johnson-Jennings et al. 2020b; Walters et al. 2018). UHN leadership agreed that land, seen as including the waterways and oceans, holds the unique ability to connect individuals across time and generations. It further creates a mental/abstract space for building relationship and pushing one out their comfort zone (Fernandez et al. 2020; Johnson-Jennings et al. 2020a; Schultz et al. 2016).

The UHN leadership described the land and water as integral to their daily life and wellbeing. UHN leadership and elders also supported that land and waters can actively guide people on their healing journeys and can alter their perceptions of place. Being on the land can facilitate the realization that individuals are connected to a larger whole within their landscape and universe. This realization of connection to place further fuels health journeys and encourages sustainable, long-term behavioral changes (Walsh et al. 2018). This relationship with place is, thereby, inextricably linked to Indigenous traditional ways of being in relation with relatives. Metaphorical examples of relational place orientations can be seen in Indigenous constructs of place as relational referents, such as to “mother earth” or to rocks as “grandfathers.” Walters and colleagues (Walters et al. 2011, p. 168) note: “We converse with place as if with relatives. Place is part of our ancestral heritage, our present, and our future. It links us in immediate and visceral ways to our past, present, and future. In this sense, Indigenous peoples emerge from the place and have a bidirectional relationship of caring with place—place cares for us and we care for it.” Houma people, who have many stories of wind and water, have been described as being acutely attuned to their sense of place, especially during times of hurricane or disaster (Dardar 2008). They further have been described as collectively uniting to recover from devastation in a calm and caring ways (D’Oney 2008). For this study, UHN leadership reiterated their view of land as important for health and their need to collectively address their health in place.

UHN and researchers collaboratively decided that revisiting Houma ancestral sites would be key to identifying a collective health framework. Land-based healing interventions have previously involved either revisiting sacred/ceremonial sites, tribal territories, and/or lands in which they were removed or experienced mass trauma (Johnson-Jennings et al. 2020b; Parlee et al. 2005; Walters et al. 2018). Given that land can be seen as embodying trauma—especially if individuals have not often visited the location (Manzo 2005), transforming narratives of trauma into resilience can become a powerful reframe to support one’s healing journey (see Yappalli in Walters et al. 2018). Thus, land-based healing interventions that revisit traumatic places and include cultural interpersonal supports, and therapeutic interventions could provide a venue for transformation of traumatic narratives. In essence, an individual can reflect upon their ancestral narratives/experiences, the land’s resilience across time, as well as Indigenous original instruction for health and healing; in doing so, they can begin to craft a narrative of hope and resilience, instead of trauma alone. Being on the land further supports long-term behavioral changes through focusing on the future generations. Land-based healing is particularly important for increasing Indigenous cultural continuity for healing, while addressing the trauma of land dispossession (Brown et al. 2012).

After learning about the land-based healing randomized controlled trial Yappalli, loosely translated as to walk with mindfulness in the Choctaw language, UHN leadership and Dr. Billiot, UHN tribal citizen, decided to contact the two leading Choctaw scientists and authors (Dr Johnson-Jennings and Dr. Walters). Yappalli, a National Institute of Health/ NIDA, randomized controlled trial R01, is a land-based healing intervention, which engages Indigenous women in the community in retracing their historically traumatic removal trail and retelling ancestral historical narratives in order to reconnect with their ancestor’s vision for the future generation and ancestral teachings around food and land (Walters et al. 2018). Through focusing on a health promotion leadership model, Yappalli has supported Choctaw women participants becoming community health leaders- while learning ancestral teachings and wisdom around health, wellbeing, and food and land practices. In this way, land serves as an opportunity to transform narratives of trauma into hope and resilience and provides the space and place to reinstate healthy relationships. UHN sought to co-develop a similar intervention for their community with the Yappalli research scientists.

2. UHN Returning to Our Roots Land-Based Healing Intervention Research Design

In 2015, UHN established the goal to address the activity level and diet of tribal citizens, who are currently experiencing high levels of environmental change and trauma and increased health risks. Therefore leadership sought the assistance of the authors to co-develop a UHN health framework by adapting the Yappalli intervention. Through addressing the sites of trauma, they hoped to reconnect with the vision of their ancestors for their health today. Given that the Houma are matrilineal, as are the Choctaw, they also chose to select Houma women leaders who often transmit the cultural knowledge of health to the next generation. They also wanted to follow the health promotion leadership framework and strengths-based approach used in Yappalli. Thus, this project first sought to specifically determine the feasibility of a cost efficient, sustainable, and culturally grounded land-based healing project. The second aim was to identify an initial UHN health framework to be utilized for developing future health interventions.

2.1. Methods

In collaboration with United Houma Nation, drawing from the community-based participatory research framework (Wallerstein and Duran 2006), the authors co-developed and implemented the United Houma Nation-led, Returning to Our Roots (RTOR), land-based healing pilot that re-traced the forced migration of UHN ancestors to their present-day location. They sought to observe and conduct case studies as UHN mapped the route taken by ancestors to reconnect with traditional, healthy culture and lifestyles to reduce chronic diseases among tribal citizens. This ground-breaking research program drew from the socioecological frameworks (Naar-King et al. 2006) to identify the social determinants of health including individual levels of influence through behavioral, physical/built environment, and sociocultural domains of influence (i.e., identifying ancestral teachings and visions for health, that enhance cultural and land connectedness). Additionally, the Indigenist Stress-Coping Model, which emphasizes Indigenous resiliencies and cultural coping factors as buffers for health (Walters et al. 2002), undergirded the conceptual focus and data analysis.

The principal investigator/PI, Dr. Johnson-Jennings, a Choctaw tribal citizen, scientific director, associate professor, and clinical health psychologist; and the co-PI, Dr. Walters, a Choctaw tribal citizen, social worker, scientific director, and associate dean, led the project with UHN tribal citizen, social worker, and research scientist, who was at the time a student researcher. After the Tribal Administrator (who also holds the title of Vocational Rehabilitation Director) and PI held a community feedback session, the PI and the Houma student researcher co-developed a 7-day outdoor experimental excursion/intervention retracing Houma’s forced migration route (Hina), with the co-PI providing ongoing consultation. Given the tribes matrilineal culture, they sought to recruit 20 UHN women, who had an interest in health promotion and reconnecting with their ancestor’s vision for them. Recruitment occurred via community citizens across six parishes, social media sites, and the community newsletter. Inclusion criteria included being Houma, a woman, and between the ages of 18–45. However, two women elders were also included to help guide the intervention and were part of the 20 women who completed the intervention. A pre-assessment meeting and several post meetings occurred, as led by the UHN community researcher. During these meetings, the Yappalli health intervention and curriculum were presented. The UHN leadership and elders assisted in modifying the curriculum for Houma. In particular, the journey was modified to include land and water/paddling, which is culturally significant. Furthermore, the Houma language, history, and stories were integrated into the curriculum. The PI and Houma student researcher were onsite, travelled, and camped with the participants. This route covered 126 miles over seven days where participants walked an average of 4 miles per day and paddled canoes an average of three miles per day. Daily group activities were integrated and included yoga, stretching, and contemplative reflections at morning light.

During the actual walk, researchers tested field operations curricular implementation, feasibility, and acceptability of the intervention with the participants, as well as conducted pre and post interviews and two focus groups. They sought to conduct a case study to identify cultural health beliefs in order to inform a culturally relevant health framework. The UHN Tribal Administrator and her community-based team recruited 20 UHN women and directed UHN logistics with support from the student researcher. Through reviewing historical documents, UHN finalized the route and sites of interest.

Participants conducted a body composition analysis pre and post walk to inspire increased knowledge about leisure-time physical activities and healthy food habits. The researchers initially piloted a health pre-assessment survey, which was preapproved by UHN leadership; however, many participants spoke Houma or French as their first language and had difficulty completing the surveys on their own. The UHN leadership and researchers considered the participants’ feedback and determined that the survey’s reading level and length were too burdensome for the selected sample. Therefore, the researchers chose not to require a post survey. Instead, participants were given the opportunity to reflect on the survey and the feasibility of future surveys during post intervention interviews and focus groups. Participants further were requested to complete daily reflections. This included the following: “Today we are asked to reflect on…” Questions to guide our reflections: What do our ancestors want from us? What do we want for ourselves? What kind of ancestors do we want to be for our children?”

2.2. RTOR Curriculum

The United Houma Nation co-developed the land-based healing curriculum, using the Yappalli curriculum as a guide. In doing so, they identified historical accounts of Houma women leading their community to safety and ancestors suffering unbearable struggles to ensure the survival of future generations. They identified sites to visit, which included mounds and waterways in order to reconnect with ancestral instructions (i.e., Original Instructions). Key Houma massacre and removal sites were further identified in order to consider resilience and resistance. Similarly, the ancestral ceremonial sites and waters were included to consider revitalization of ceremonial practices and spirituality. The UHN further requested to visit the French consulate to focus on the blending of Houma and French culture that continues to thrive while resisting colonization. UHN also co-developed their daily curriculum, which presented historical accounts at each site and allowed time for reflection. On day one, the participants visited their historical tribal territory before European contact, Tunica Hills, which is north of the Baton Rouge. Here they symbolically declared that they were making a claim for their future health and redeclaring this as their territory. This symbolic act set the stage to focus on their health and the future. Through making land central, they sought to transform narratives around trauma into hope and resilience, modeling such approach from the Yappalli project. Themes included the following as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

United Houma Nation (UHN) Returning to Our Roots curricular themes and focus group questions as based on Yappalli.

2.3. Reflexivity

Reflexivity was fostered by having multiple investigators on this study. While the co-PI, Dr. Walters, did not travel with the team, she was available via telephone for consultation around interpretations and research decisions. Further the PI, Dr. Johnson-Jennings, and, then, student researcher, Dr. Billiot, held daily dialogue regarding their interactions with the participants, discussed potential biases and interpretations, and kept daily field notes. This was especially important given similarities between Choctaw and UHN culture and the need to identify even subtle differences. Furthermore, 11 individual post-walk, semi-structured interviews were conducted after the walk to further permit participant reflection following the questions identified in Table 2.

Table 2.

UHN Returning to Our Roots semi-structured interviews and participant questions as used in the Yappalli Project.

2.4. Rigor

The Houma student researcher, who conducted the interviews, had prolonged engagement with the community from October 2011 to the present day. To reduce researcher bias, the research team utilized peer debriefing support and triangulation. Triangulation strategies are seen as the strongest method to reduce threat to trustworthiness of reactivity, researcher bias, and respondent bias (Padgett 2008). In this study, we utilized two methodological triangulations to analyze data through constant data comparison and NVivo coding. The second triangulation methods utilized was data triangulation in which we analyzed data from observations from pre and post intervention, intervention focus group interviews, and post-intervention individual interviews.

The authors built rigor into the design of the study through peer debriefing and support. The co-PI and senior author supported the researchers in the field with socioemotional support, integrity (i.e., keeping the field researchers honest in reflexivity), and suggested ideas to reduce barriers. This method to increase trustworthiness of researcher bias is often overlooked (Padgett 2008) but served as an essential component of the intervention.

2.5. Relationship

The PI, Dr. Johnson-Jennings, and Co-PI, Dr. Walters, have had a long-standing research relationship for the previous 18 years. Historically, the Choctaw and Houma were known to support one another in times of trouble. Further, UHN culture overlaps with Choctaw in some language, cultural norms, beliefs, and history. At the same time, UHN remains a distinct tribe and culture that has evolved and intermingled with French ancestry. Through a research fellowship, the PI’s met the Houma student researcher, Dr. Billiot, who was a mentee and predoctoral fellow at the time of this research. The researchers’ tribal histories and relationships fostered a rapid bond between the three. While at the same time, the Co-PI, Dr. Walters, has served as senior mentor for Dr. Johnson-Jennings during her career, and both have served as mentors for the then student researcher, Dr. Billiot.

3. Data Analysis

The authors utilized the constant comparison coding method for this study, in which the process flows from raw data, then preliminary codes, to final code (Saldana 2015). Participants’ expressions and vocal emotions were audio recorded and were directly written into hard copy of raw data. This minimized the distortion of the meaning in interview. All interview transcripts were analyzed in similarity and differences, frequency of concepts, sequence of statements, correspondence to events and stimuli, and causation (Hatch 2002). The first participant’s interview was initially codified with notes being taken, clusters conducted, and then larger categories developed. The codifying process for subsequent interviews influenced the general themes, which were then tabulated based on the data. The authors analyzed each sentence of the participant transcripts, documented the emotional changes in audio records, and transitioned into preliminary coding based on the relationship to the land-based healing. The team integrated and categorized the final codes by the outcome of preliminary codes.

3.1. Findings

Qualitative results from this Indigenous led pilot study indicated that the UHN Returning to Our Roots was a feasible pilot project, which provided reconnection to the land and prompted the development of a Houma health framework. The initial themes included the sociocultural determinants of health and cultural buffers including (1.) place and creating space, (2.) ancestors, (3.) spirituality/mindfulness, (4.) cultural continuity, and (5.) environment and health. The reconnection to land was central to renewing relationships with ancestors (aihalia asanochi taha), others, and body. This re-engagement with the land and waters contributed to subthemes of developing stronger tribal identities, recreating ceremonies, and increased cultural continuity and identity—including understanding of “what it means to be Houma.” It also transformed trauma narrative into ones of hope and resilience for future generations. These are the key components of the Houma Health (Uma Hochokma) Framework (see below).

3.1.1. Place and Creating Space

Through placing land, including water, as central, participants reported new relationships with historical Houma places; i.e., ancestral mounds, waterways, sites of historical ceremonial dances/stomp dances, massacre sites, and the French consulate. Through examining the transcripts, we found that participants renewed perceptions of place and created a mental space to reflect upon their Houma culture. Participants reported feeling connected to the place of their ancestor’s, the historical significance of the site, as well as their present relationship to historical trauma, their ancestors’ and self-journey and resilience. “…think our ancestors envisioned for us to be able to be proud of who we are, of course. I mean that sounds kind of cliché but it’s not. Be proud of who we are. Don’t let our history die. I think they would have been saying, look, learn and continue to pass down. Otherwise, their journey would have been in vain. Their struggles would have been vain. Their lives would have been in vain, if we don’t pass it on down.”

The transcripts further reflected subthemes of finding “beauty” in place and among nature. “…You feel still very connected, but you go up there and your cellphone doesn’t work, and you can’t hear the highway. All you can hear is the waterfalls. I love it there. It’s so beautiful. It’s such a great space.” Along these same lines, several participants reported having a form of mindfulness in place; or being aware of feelings and beauty, despite external occurrences. Water appeared to elicit mindfulness more than land alone. “You feel still very connected, but you go up there and your cellphone doesn’t work, and you can’t hear the highway. All you can hear is the waterfalls.” Others noted an internal happiness that elicited from being in nature, “Just kind of laughing, giggling and just to kind of be there just with the nature right there. I know there were cars passing but that’s not what I connected with and that kind of stuff.”

The participants also held negative feelings related to oppressive experiences in relation to place. “Then to have all the jail oppressive feelings and know some of the horrors that now take place there was really overwhelming. That was really overwhelming for me.” A flooding of emotions was mentioned by many standing in these traumatic places. This then spurred ceremonies for healing self, body, mind, spirit, and the land. In fact, the land was referred to at least twice as an active agent in the healing process and actively influenced participants ideas of place and wellbeing.

Participants further overwhelmingly connected to sites, viewing them as places of experience to overcome fears and become “brave.” These connections included seeing their ancestral histories embodied in place, as well as well as connecting to other relations during this process. Being at these sites “Felt like family” and provided a sense of collectivism, with a focus on social relationships past, present, and future. They further described the need to find one’s path as part of the collective Houma Nation.

3.1.2. Ancestors

Through reconnecting with their ancestral sites of trauma, the participants reflected and contemplated their ancestors’ past resilience and the sacrifices that they made for the future generations. In particular, visiting the massacre and removal sites elicited comments regarding ancestors’ strength, love, and resilience. They further often felt a strong sense of connection with their ancestors. “Not necessarily because we were there as a group, but like for myself in like just quiet times and just feeling very rooted and very connected.” The participants saw their ancestors’ traumatic experiences as sacrifices that they made for the current generations’ survival, which spurred deep appreciation. “I think it gave me a great appreciation of what our tribal member in the past went through. The tall trees. The gullies. I’m sure they had to struggle a lot. Sometimes as tribal members now…”

The participants drew strength from the places that embodied trauma, remarked about their resilience as the future generation, and their need to heal through ceremonies. While conducting ceremony the participants noted their ancestors’ love and visions for them. Through retraveling in their ancestors’ footsteps, the participants reported appreciation and responsibility. “Grateful for their sacrifice and survival. I felt proud to be related to somebody or a group of people who have survived so much and are still so strong. That was … I feel pride in that…” Participants further felt that their ancestors wanted them to carry on these land-based practices with their more than human relations. “I think in spaces like we had, we weren’t in the desert, nature provided us with everything we needed, and I think they would have wanted us to know how to use that, not just the animals or fishing, but like the plants, the remedies, the just being at peace in nature. I think that’s what they would have wanted.” Inherent within this quote is the idea of being in balance with the land, water, and place.

3.1.3. Spirituality/Mindfulness

Land and water further actively reconnected participants spiritually. Participants described feeling more spiritual on the water and land. They further revitalized spiritual practices, such as a ceremonial dance, furthering cultural continuity while on the trip. In doing so, they reconnected to one another and the earth at a spiritual level and viewed themselves as part of a greater whole-including across time and space. Through being on the land, camping, walking, and canoeing, participants had the opportunity to collectively share in grief over cultural loss and resulting ill health. Additionally by connecting through ceremony on the sites of trauma, laughing and engaging in cultural activities, participants were able to heal. Also, participants participated in cultural traditional practices in place; e.g., basket weaving, beading, creating medicine pouches, and group prayers for loved ones, which facilitated a spiritual connection with their ancestors, their tribal members, and the more than humans/animals, plants, waters, etc. In their discussions, they focused on the health of the land, the waters, and their past and future generations. Participants also discussed conflicted feelings, “I felt like there was a spiritual connection there [Angola Louisiana State Prison], but I felt like it was interrupted because our history is misrepresented. The ceremony there felt a little healing, not a little, but it felt healing to kind of process that and think about it in a different way.” Thus, reconnecting to the land included reconnecting spirituality even in places of ongoing oppression and trauma. There existed an acknowledgment of biased and inaccurate history that may have interrupted their spirituality, and otherwise encouraged the continuity of marginalization. Yet at the same time, they were able to process such and initiate healing upon this location. This facilitated a transformation in the viewing of trauma at these locations and an assertation of control. Being in the same space as their ancestors, including both sites of ceremonial grounds and trauma, the participants began to focus on spirituality, healing from the oppression and disruption of cultures, as well as seeking to initiate change.

Through a Houma view of place, the participants created a new place for ceremony. Through the process of ceremony, they were able to feel, at times, overwhelming emotions and create healing as they began envisioning themselves as future ancestors. This furthered their focus on cultural continuity and identification as a tribal citizen. “I think it only strengthened my identity of being Houma. I felt proud and I felt grateful that they made the sacrifices that they made to be together, and to be with family, and to have survived the long trek.” They further initiated more interest in plants and medicines and their use for healing, reinvigorating ancestral ceremonies, such as the stomp dance, and feeling more spiritually connected to places in general.

3.1.4. Cultural Continuity

The participants frequently discussed needing to further cultural continuity in order to heal during the RTOR land-based healing intervention. Through being on the land of their ancestors, participants reconnected with the importance of continuity. They saw their culture as living and not stagnant. “Culture’s living, it’s a living thing. It’s not dead or whatever, so whatever the Houma culture looks like now, that’s the culture. That really resonated as, like I said, talking, and going through all the stuff planning through this trip of looking back on our stuff…” Furthermore, being on the land symbolized their desire to keep their culture moving forward. “Oh, we used to do this, we used to do that.” Well why don’t we now? That can happen, as long as we continue to further our culture, and continue to move along with the tribe.” They also voiced an overall strength in having a Houma identity. The participants further felt strength and pride in their ancestors and themselves for maintaining a Houma identity. In essence, Houma place symbolized their need to carry their identity, culture, and knowledges into the future. “I want them to be able to walk or sit somewhere that I once was. Even something as simple as sitting in my house, and just sitting down and remembering.” Most saw cultural continuity as a collective responsibility in which past, current, and future generations must contribute. “…it’s not only just being a member, but I have a responsibility towards our preservation and that other people have those experiences and making those connections.” They also saw maintaining cultural practices including food gathering (fishing, hunting, and gathering) and craft (i.e., basketry, beading, sewing, etc.) as important for a recommitment to health. “…I think it’s just that stronger commitment. I think as well it reaffirms that commitment of, I have a responsibility to the tribe, so it’s not only just being a member, but I have a responsibility towards our preservation and that other people have those experiences and making those connections.” Furthermore, by reciprocally creating new views of place while in sacred or territorial place, participants were able to engage in ceremonies and traditional activities, thereby furthering cultural continuity.

3.1.5. Environment and Health

Participants linked the environment to their health similar to other Indigenous groups (see Jennings and Lowe 2014). For instance, when the “children don’t play outside,” the participants saw this as unhealthy. Participants further discussed the impact of global warming and climate change. In particular, they noted the change in seasons and weather patterns. “I’ve never seen a tornado before when I was growing up until recently. It’s like, “What’s going on?” Is it the green gas? The ozone layers?” Many also discussed how many places “looked different,” “the trees are dying the water is darker,” “the fresh water is not safe to swim in or drink.” Thus, the health of the environment appeared to influence their view of health today. Secondly, the participants discussed current land traumas including the BP oil spill, the pollution of land and waters, and loss of land by brackish waters. “What about the natural order of things? At what point are we going to realize we can’t keep messing up the natural of things? At some point … Even with this … With coastal erosion, and these oil spills, and the oil line, it’s like eventually, Mother Nature is going to take back what was hers, whether you give it to her or not. I just really … I really feel like there needs to be more of an effort for all of us to do our part when it comes to stuff like this.” Finally, the participants also recognized the impact on the more than human relatives during the intervention and shifted their view of connectedness to their ecology. “The environment, I’ve been concerned about the environment... I remember the birds that you pointed out like how the birds were following us. I’ve kind of been connected. I mean I’ve always thought about the animals being part of our ancestry, but it wasn’t until then that I kind of started doing that, watching for animal reactions, how they are whenever we are around. That was a little bit of a shift.”

3.2. Feasibility

The participant feedback guided the researchers to tailor future efforts on teenage youth. They saw the RTOR as highly feasibility in terms of bringing people together, addressing physical health and behavioral choices, and in learning about the UHN history. Difficulties were further voiced around age cutoffs, surveys being in English and too long, leaving out some elders, and the inability to bring youth along. UHN leadership reflected and wished to build land-based healing capacity for UHN in the future and would like to target youth.

3.3. Houma Health: The Uma Hochokma Framework

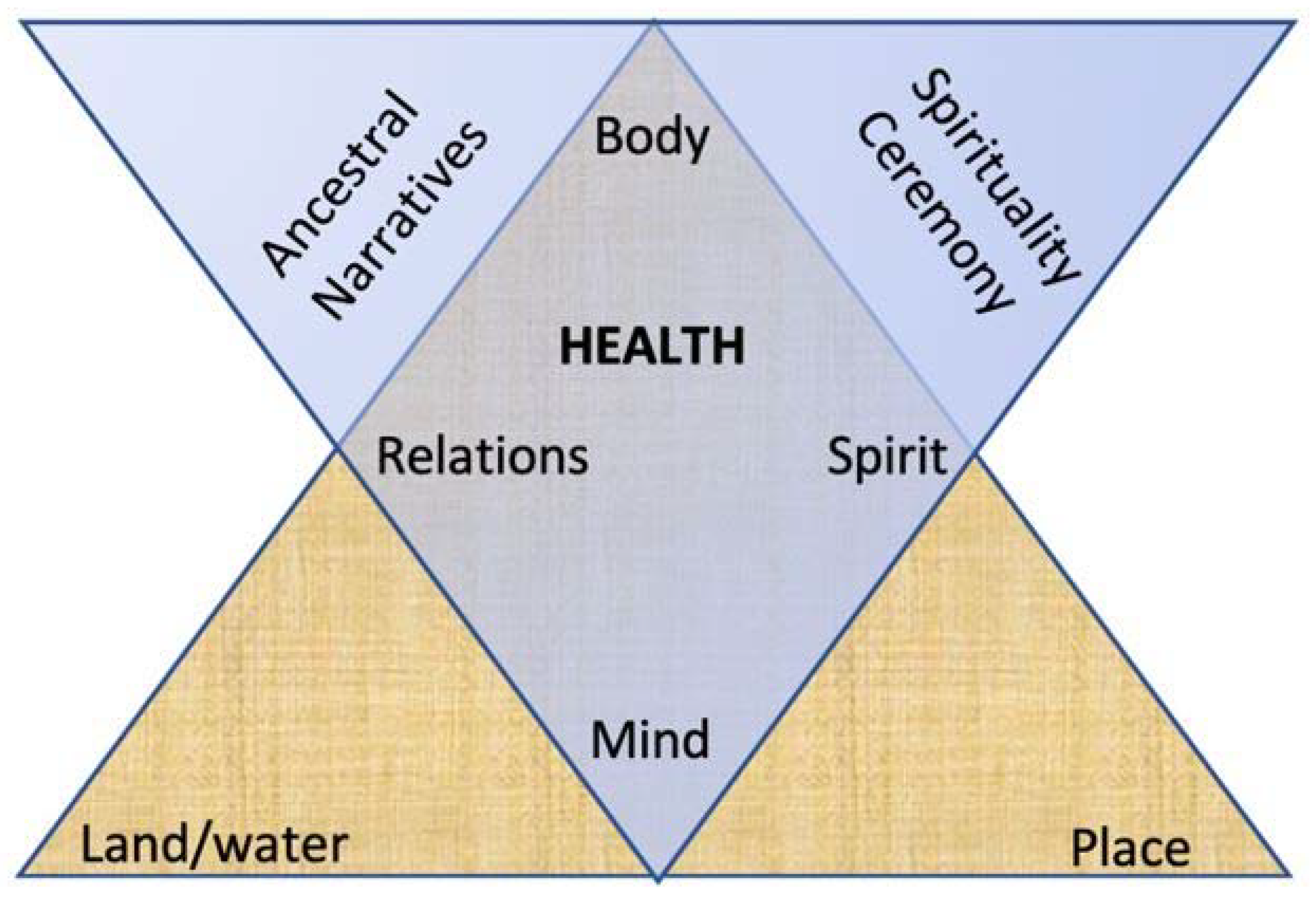

The data generated from this project provided the structure for the development of a Houma health (Uma Hochokma) Framework. The Figure 1 depicts a triangular path of mountains or one’s life journey, as is traditional to Houma, and related Muskogean cultures. The aligned bottom left and right triangles, or the path of change, were chosen to represent the individual’s healing journey of an individual during life’s ups and downs. This path begins with the land and water, each being equal in significance and representing mother earth. Then, the path leads to relations that are central for health. The mind and spirit then interact to define and experience place, or how an individual interprets his or world. Not only did UHN participants see land as central for their healing journey, but water was equally important for healing and change. Meanwhile, land and water were described as being perceived by the mind. The mind forms the sense of place, as influenced by one’s spirit, during one’s journey of health. The inner, imposed diamond of resilience is a common pattern in Houma culture as it represents the rattlesnake for most Muskogean/Houma peoples. The Houma word for rattlesnake is santè lo meaning sacred snake and symbolizes resilience and adaptation (Brown and Hardy 2000); both of which were found important to a Houma view of health. This rattlesnake diamond holds the sacred mind, which interacts with the land/water and place and is dangerous as well as healing, like the rattlesnake. The diamond also contains the body, spirit, and relations that must be in balance with the mind for health to occur. The mind is counterbalanced with the body, both needing the other to exist and to maintain health in order to thrive. Then, the spirit and relations, or relationships and responsibilities to others across generations, are counterbalanced within the diamond of resilience. All of the diamond elements need to be in balance for healthy coping, supporting resilience, and overall health, which is centered within the diamond.

Figure 1.

Uma Hochokma Framework.

Meanwhile, the land/water, body, and place are critical elements involved in land-based healing and are symbolized within the bottom large triangle that forms the base of health. Each reside within one foundational angle as they interact reciprocally, in balance, and represent locations where embodiment of trauma and ancestral love and healing can occur. The two upper triangles—not overlapping—are symbols of the ancestral narratives and the spiritual ceremonies that facilitate changes and support transformation of trauma to resilience, or transcendence. For example, in our study, UHN women initially perceived place from historically traumatic, colonial views. However once strengths-based ancestral narratives of place were learned in relationship with land and water, the women initiated a spiritual response, often in the form spiritual ceremonies, spurring transformation and healing. While the body engages upon the land, the spirit further interacts with relations (both human and more than human), simultaneously eliciting mindfulness/contemplative practices.

This Uma Hochokma Framework further symbolizes that when one engages upon the land physically, mentally, and spiritually; bodies become physical representations of ancestral survival and resilience. We found that women perceived their physical being as a symbol of hope, which increased the desire to further cultural continuity and wellbeing among the collective. In other words, ancestral narratives gathered from the land can transmit strength and initiate change across generations; thereby, overcoming the spiritual disconnections that may have occurred through trauma. Additionally, as seen our study, Houma can engage in ceremony with the land not only to heal their spirits, but also to heal the land, as voiced by the Houma women. Through creating new ceremony or revitalizing ancestral ceremony, Houma can further their cultural practices, heal the land, and continue their culture for the future generations through a journey of healing.

4. Discussion

“Walking. I am listening to a deeper way. Suddenly all my ancestors are behind me. Be still, they say. Watch and listen. You are the result of the love of thousands.”—Linda Hogan quote

As Indigenous Muskogean poet and novelist Hogan states, land and place serve to reconnect Indigenous peoples to their ancestors, their resilience, and their love, as supported by our findings. This community engaged, culturally grounded study sought to reconnect UHN participants with their ancestral land and experienced historical trauma in order to encourage identifying ancestral narratives of resilience, UHN healthy cultural protective factors, and assess if reconnecting to the land would encourage participants to practice healthy behaviors. This study identified Houma social determinants of health related to the colonialism, behavior, land, and sociocultural practices/narratives that can help mitigate health disparities and are represented in the proposed framework. Overall, this study found that land can serve as a therapeutic site for healing through reconnecting UHN citizens to both ancestral knowledges and stories of resilience, as well as viewing self as part of a larger collective. These findings also imply that revisiting historically traumatic places encouraged renewed commitment to cultural continuity and health behaviors—particularly when these places are approached relationally, with ceremony. While place can bring into the conscious ancestral histories, as well as inaccurate settler colonial histories (Gustafson 2001), we found that a land-based healing intervention can counteract settler colonial historical trauma responses and spur healthy behavioral changes. It also permitted for the therapeutic healing of trauma through reclaiming historic ceremonies and creating space for cultural continuity. Through this journey, UHN was able to develop their health framework (see Figure 1), which can be used in future studies to support resilience and thrivance.

4.1. Place and Creating Space

The UHN Returning to Our Roots study supported Indigenous worldviews indicating that no distinction between people and the land exists (Baskin 2016). Houma participants viewed the water and the land as their mother/relative. As seen in Figure 1, land and water function as a physical location that holds cultural notions of place. This study reinforces that being on water and land creates meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples and are critical in their journey to health. Our participants further felt spiritually and ancestrally connected to locations that their ancestors experienced sacred as well as traumatic events. In addition, our findings imply that place, like relatives, can serve to build relationships with others and a sense of community. Visiting place can further facilitate a stronger sense of Houma identity.

Land also served as an ideal location to decolonize notions of place, while simultaneously supporting cultural practices and identity. For instance, participants’ memories were initially vivid and painful regarding traumatic ancestral places that were not frequented prior to the intervention, as seen with other research (Saar and Palang 2009). Yet after the participants physically reconnected with the land, these colonial sites and memories were replaced with even stronger Houma narratives of ancestral love. Though settler colonialism encourages silencing of the trauma and the dispossession, the land can continue to actively transmit both loss and life once a relationship is re-established (Tuck et al. 2014). Through revisiting the land, the Houma women were able to assert agency, claim the space and pain of their ancestors, and create a Houma space to heal through ceremonies and reflections, supporting prior land-based research (Byrd 2011). In alignment with non-Indigenous literature (Kearns and Moon 2002), our findings reinforce that place, in terms of ancestral water and lands, matters for health and can serve as a strong facilitator for reflection and behavioral changes. Given Indigenous views of land and wellbeing, land can serve as an important context in which to conduct a culturally appropriate, health intervention.

4.2. Renewing Relationships with Ancestors (Aihalia Asanochi Taha)

Land and water served to reconnect Houma women with their ancestors and their teachings. This included the Houma women engaging with the ancestors who were seen as embodied within the waters and land. Our findings imply that land holds not only trauma, which is necessary to heal, but also ancestral love and teachings. Through situating self within the context of having loving, resilient ancestors, the women were able to transform notions of trauma into healing. They further readily reflected upon their role as a future ancestor and the need to engage in healthy behaviors for the future generations. In essence, they altered the view of themselves cloaked within ancestral trauma, and instead developed a sense of self that descended from ancestral strength and powerful love that fed future generations. Land further held the space to not only reconnect with the ancestral narratives, but also to develop a relationship with their teachings about foods and land practices, as seen in prior research (Johnson-Jennings et al. 2020a). Our findings support that by reconnecting with ancestral practices on the land and water, land can transmit and support Indigenous health behaviors (Dobson and Brazzoni 2016; Parlee et al. 2005). Therefore from an Indigenous view, land may be effective in inducing healthy behavioral changes through reconnection with the ancestors, but more research is needed to determine if long-term behavioral changes exist.

4.3. Spirituality/Mindfulness

Houma women created meaning and transformed their view of ancestral trauma into resilience by being contemplative and mindful, as well as having spiritual, collective discussions while in place. It is through reflectively and mindfully revisiting place that individuals can create change in their place-based narratives, thereby deciding new meaning (see Manzo 2005). Land from an Indigenous lens is believed to hold a spiritual healing power that can assist during pain or other turmoil (Radu et al. 2014). For instance, Houma women described healing from the trauma felt upon the land and waters by being mindful while reconnecting with land and/or through ceremony. Mindfulness, which has been described as awareness of internal and external realities (Creswell 2017), has been found as a culturally appropriate and an effective approach among Indigenous communities (Dreger et al. 2014). While mind–body interventions have been proposed to increase wellbeing and reduce disease (Kotecki et al. 2015; Ryan et al. 2018), little mindfulness research has been conducted among Indigenous groups. In our study, reconnecting to land, in particular, created the mental state to be present, or mindful, as found with other studies (Chinn 2014). In this case, mindfulness was further triggered by being in nature, near water and animals. Most often this included reflecting on one’s ancestral narratives of place, strength, and resilience; as well as self-reflection on health, behavioral choices, and considerations for becoming a good ancestor. Hence, water and land appear to induce a commitment to healthy behavior changes through contemplative practices.

Similar to “therapeutic landscapes” and “blue space” used in the field of geography (Foley and Kistemann 2015), water encouraged mindfulness and place-based healing ceremonies in our study. Participants connected to ancestors’ and ancestral practices through the water and wished to conduct ceremony near water, which has been found an important place for healing (Foley and Kistemann 2015). This finding aligns with other research that healthy blue space promotes healing through reducing stress and increasing physical activity (Foley and Kistemann 2015; Wheeler et al. 2012). Particularly from an Indigenous perspective, engaging in ceremony can induce mindfulness by encouraging an accepting attitude of all internal and external experiences (Dreger et al. 2014). Thus, being on the land or water may actually be an ideal location to conduct mindful, contemplative practices, as opposed to an indoor location. Given Indigenous teachings often support non-judgemental awareness of one’s surroundings, future research should consider the element of Indigenous mindfulness in land-based healing and how this could improve health.

Furthermore, water and sites of trauma initiated the creation of space for ceremony and strengthening cultural identity, which correlates with better health outcomes (McIvor et al. 2013). Through experiencing the land and waters, the women increased their knowledge about their relationships to the plants, animals, and sky beings. Hence, being on the land/water can elicit the needs to identify, develop, and maintain a balance of relationships within the environment. Similarly, Meyer (2014) found that Native Hawaiians view the land as another ancestor and teacher, as “we connect to her we connect to ourselves” (101). Therefore, healing can be facilitated through being on the land and creating space.

4.4. Cultural Continuity

We found that water and land can serve as an active agent in cultural continuity and the healing process, as suggested by Johnson-Jennings et al. 2020 and Walters et al., 2011. The Houma women were able to re-envision their narratives of cultural resilience, thrivance, and cultural continuity throughout the Returning to Our Roots intervention. This transformation of trauma often occurred through ceremony upon the land, which included both traditional ceremonies, as well as contemporary versions/revitalization of ceremony. It was through reconnecting with ancestral narratives of place and resistance that they consciously chose to further their cultural practises and identity. By further holding the space for one’s body, spirit, and mind to engage, the water and land evoked a reciprocal relationship with participants and their desire to increase their cultural involvement, identity, and transmit cultural knowledges on to their children and future generations.

Increasing cultural continuity through reconnecting to the land can have broad implications for health and wellbeing. Increased cultural continuity, including land-based activities, is associated with increased overall health status, mental health, and wellbeing (Auger 2016; Newell et al. 2020). It is further associated with lower prevalence of diabetes type 2 (Oster et al. 2014). Cultural continuity has further been argued as a social determinant of health that influences proximal, intermediate, and distal health factors for Indigenous groups (Greenwood and Leeuw 2012). Therefore, as seen within our study, reconnecting to ancestral lands and increasing cultural continuity may mitigate health risks for the UHN and other Indigenous groups.

4.5. Environment and Health

Land does not only serve as the place for community resurgence and decolonizing settler colonial views of land (Corntassel and Hardbarger 2019) but can also serve in a capacity to heal individuals and reinforce caretaking of the land in the face of climate change (Parlee et al. 2005; Pearce et al. 2015). A recent UHN dissertation study, conducted after this intervention, found that 97% of 152 UHN tribal citizens reported a strong connection to place (Billiot 2017). Our findings indicated that this strong connection to place can guide healing the land. The Houma women developed an increased need to care and heal the earth for their own health. Many Houma stories exist regarding how to care for the soil and listen to the land, tend to it, and help mitigate hurricane risks. Furthermore, these stories may continue to guide Houma families’ wellbeing and disaster preparedness, if they can be retold (Dardar 2008). With climate change and environmental degradation, UHN’s health risks have increased and many families have become isolated (UHN 2015), leaving them without access to these ancestral narratives. Hence, land-based healing can provide space to share stories and facilitate reciprocal healing and environmental caretaking.

Returning to places containing ancestral knowledge is especially important for UHN health needs given the aforementioned extreme loss of land, climate change, and assaults upon their environment; e.g., oil spills, disruption to natural land based, hurricanes, erosions, etc. (D’Oney 2008; UHN 2015). Furthermore, Houma participants who had exposure to environmental changes were recently found to have poorer reported health outcomes (Billiot 2017). Thus, reconnecting to Houma ancestral land may be particularly important in buffering the effect of environmental changes. In fact, water/land-based healing and place can similarly be adapted to many other Indigenous and marginalized communities who are forced to relocate due to climate change, environmental changes, and exploitation.

4.6. Uma Hochokma Framework

Overall, we found that a land-based healing intervention was feasible and assisted in developing a Houma specific health framework, Uma Hochokma Framework (see Figure 1). The Framework reflects the UHN participants process of initiating healthy behavioral changes and increased cultural practices. As found in other land-based research, land offers both a place and space in which relationships can be built for respect and love (Radu et al. 2014). Our findings further bolster that Houma cultural notions of place are meaningful for health, as seen with other Indigenous groups (Dobson and Brazzoni 2016). UHN relational place orientations included connecting to water and land for health and continuing one’s health journey. The derived culturally grounded, Houma Health Umo Hochokma framework supports relationships and balance with land, place, and beings. Through engaging with mother earth, UHN participants were able to heal through the mind, body, spirit, and relationally. They were further able to reconnect with their ancestors, original instructions, culture, revitalize their spiritual practices, and increase their commitment to healthy behavioral changes.

After our findings were disseminated to the community during public forums and among key stakeholders, UHN leadership was able to utilize these findings to guide other health interventions around the importance of diet and exercise. UHN leadership further met and decided that cultural continuity and addressing youth wellbeing were critical. Hence, these findings have supported the development a Houma youth land-based healing intervention, which will increase cultural identity, cultural continuity, traditional ecological knowledge, and support healthy lifestyle choices. Furthermore, our findings have implications for Indigenous communities across the globe seeking to engage in land-based healing practices. The UHN modified the Yappalli curriculum for their specific cultural needs. Though Houma and Choctaw are culturally similar, our pilot project demonstrated that cultural tailoring can occur for other Indigenous groups by thoroughly engaging the community through each step. Moreover, reconnecting to land and waters may prove to induce long-term health behavioral changes, but more research is needed to determine if these land-based practices are sustained. Finally, future research needs to examine if similar results could occur among other Indigenous groups, youth, and men.

5. Limitations

The cross-sectional pilot study was conducted with a convenience sample of 20 UHN women, who self-selected to become health leaders. Furthermore, these findings relied upon self-reports and qualitative narratives. More research is needed to develop culturally appropriate, biometric measures for a larger sample. Thus, this study serves as a pilot to build a health framework and to test the feasibility of a land-based healing initiative. Though feasibility and initial health behavioral changes were encouraging, more research is needed to determine how land-based healing can lead to sustained health outcomes including both biometric and feasible psychometric measures.

6. Conclusions

Overall, we found that land-based healing is both feasible and relevant to transforming narratives of trauma and spurring healthy behavioral changes, as well as cultural continuity, among a coastal Indigenous population. Not just land but water can serve as important catalysts for addressing settler colonialism, transforming narratives within place, and spurring recommitment to health. Water and land can further induce ancestral connection, mindfulness, and spirituality and serve as active agents in healing. They can further actively induce behavioral changes within an Indigenous framework. More research is needed to determine how health interventions on the water and land can best be utilized to further health and overall cultural continuity for Indigenous peoples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.-J., K.W., and S.B.; methodology, M.J.-J., K.W., and S.B.; software, NViVo; validation, through triangulation of all authors; formal analysis, M.J.-J., K.W., and S.B.; investigation, M.J.-J., K.W., and S.B.; resources, M.J.-J., K.W.; data curation, M.J.-J., K.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.-J.; writing—review and editing, M.J.-J., S.B. and K.W.; visualization, M.J.-J.; project supervision, M.J.-J.; project administration, M.J.-J., S.B.; funding acquisition, and M.J.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding through University of Minnesota-Duluth, University of Washington, and the Greater New Orleans Area Foundation. This article was further supported in part by the National Institute of Health R01 RCT Yappalli Choctaw Road to Health; (R01DA037176).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge UHN representative, Lanor Curole, who assisted with co-development of the curriculum, project administration, and review of the manuscript. We would also like to acknowledge the UHN leadership, elders, and key stakeholders who assisted with the RTOR intervention including, but not limited to, Lora Ann Chaisson, Chief Dardar, Louise Billiot and Margo Rosa (Louisiana Choctaw), along with many others who made this possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, Alex K., Heather Harvey, and David Brown. 2008. Constructs of health and environment inform child obesity prevention in American Indian communities. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16: 311–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agans, Jennifer P., Robey B. Champine, Lisette DeSouza, Megan K. Mueller, Sara K. Johnson, and Richard M. Lerner. 2014. Activity involvement as an ecological asset: Profiles of participation and youth outcomes. Journal of Youth Adolescence 43: 919–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, Jeff F., Basia Pakula, Victoria Smye, Virgina Peters, and Leslie Schroeder. 2011. Strengthening Aboriginal Health through a Place-Based Learning Community—ProQuest. International Journal of Indigenous Health 7: 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, Monique. 2016. Cultural Continuity as a Determinant of Indigenous Peoples’ Health: A Metasynthesis of Qualitative Research in Canada and the United States. International Indigenous Policy Journal 7. [Google Scholar]

- Baskin, Carol. 2016. Spirituality: The Core of Healing and Social Justice from an Indigenous Perspective. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education 2016: 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billiot, Shanondora. 2017. How Do Environmental Changes and Shared Cultural Experiences impact Health of Indigenous Peoples of South Louisiana? Ph.D. dissertation, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Billiot, Shanondora, and Jessica Parfait. 2019. Reclaiming Land: Adaptation Activities and Global Environmental Change Challenges Within Indigenous Communities. In People and Climate Change: Vulnerability, Adaptation, and Social Justice. Edited by L. Mason and J. Rigg. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 108–21. [Google Scholar]

- Billiot, Shanondora, Soohyung Kown, and Catherine Burnette. 2019. Repeated Disasters and Chronic Environmental Changes Impede Generational Transmission of Indigenous Knowledge. Journal of Family Strengths 19: 11. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Cecil H., and Heather K. Hardy. 2000. What Is Houma? International Journal of American Linguistics 66: 521–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Helen J., Gladys McPherson, Ruby Peterson, Vera Newman, and Barbara Cranmer. 2012. Our Land, Our Language: Connecting Dispossession and Health Equity in an Indigenous Context. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research Archive 44. Available online: http://www.fpcc.ca/files/PDF/Language/Intersections_Indigenous_Language_Health_and_Wellness_WebVersion.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Burgess, C. Paul, Fay Helena Johnston, David MJS Bowman, and Peter J. Whitehead. 2005. Healthy country: Healthy people? Exploring the health benefits of Indigenous natural resource management. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 29: 117–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd, Jodi A. 2011. The Transit of Empire—Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, Gregory. 1999. Indigenous Foods, Indigenous Health. In A People’s Ecology: Explorations in Sustainable Living. Santa Fe: Clearlight Press, pp. 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Clint, Eva Garroutte, Carolyn Noonan, and Dedra Buchwald. 2018. Using PhotoVoice to Promote Land Conservation and Indigenous Well-Being in Oklahoma. EcoHealth 15: 450–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. American Indians and Alaska Natives | Health Disparities | NCHHSTP | CDC. In Health Disparities in HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/healthdisparities/americanindians.html (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Champagne, Duane. 2007. Social Change and Cultural Continuity among Native Nations. New York: Altimira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, Michael, and Christopher Lalonde. 2016. Cultural Continuity as a Hedge against Suicide in Canada’s First Nations. Transcultural Psychiatry 35: 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn, Pauline. 2014. Place and culture-based professional development: Cross-hybrid learning and the construction of ecological mindfulness. Cultural Studies of Science Education 10: 121–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corntassel, Jeff, and Tiffany Hardbarger. 2019. Educate to perpetuate: Land-based pedagogies and community resurgence. International Review of Education 65: 87–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, David. 2017. Mindfulness Interventions. Annual Review of Psychology 68: 491–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, Steven, Sarah Curtis, Ana V. Diez-Roux, and Sally Macintyre. 2007. Understanding and representing ‘place’in health research: A relational approach. Social science & medicine 65: 1825–38. [Google Scholar]

- Czyzewski, Karina. 2011. Colonialism as a Broader Social Determinant of Health. The International Indigenous Policy Journal 2: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Oney, J. Daniel. 2008. Watered by Tempests: Hurricanes in the Cultural Fabric of the United Houma Nation. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 32: 11. [Google Scholar]

- Dardar, T. Mayheart. 2008. Tales of Wind and Water: Houma Indians and Hurricanes. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 32: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, Christina, and Randall Brazzoni. 2016. Land based healing: Carrier First Nations’ Addiction Recovery Program. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing 18: 207–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dreger, Lisa, Corey Mackenzie, and Brian McLeod. 2014. Acceptability and Suitability of Mindfulness Training for Diabetes Management in an Indigenous Community. Mindfulness 6: 885–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, Angela R., Tessa Evans-Campbell, Michelle Johnson-Jennings, Ramona Beltran, Katie Schultz, Sandra Stroud, and Karina L. Walters. 2020. “Being on the walk put it somewhere in my body”: The meaning of place in health for Indigenous women. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, Ronan, and Thomas Kistemann. 2015. Blue space geographies: Enabling health in place. Health Place 35: 157–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracey, Michael, and Malcolm King. 2009. Indigenous Health Part 1: Determinants and Disease Patterns. Lancet 374: 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, Margo L., and Sarah N. de Leeuw. 2012. Social determinants of health and the future well-being of Aboriginal children in Canada. Paediatrics & Child Health 17: 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, Per. 2001. Roots and routes: Exploring the relationship between place attachment and mobility. Environment & Behavior 33: 667–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, J. Amos. 2002. Doing Qualitative Research in Education Settings. New York City: Suny Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holm, Jeffrey E., Nancy Vogeltanz-Holm, Dmitri Poltavski, and Leander McDonald. 2010. Assessing health status, behavioral risks, and health disparities in American Indians living on the northern plains of the U.S. Public Health Reports 125: 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IHS. 2013. (Newsroom: Disparities—Indian Health Service). Available online: http://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/ (accessed on 13 March 2020).

- Jennings, Derek R., and John Lowe. 2014. Photovoice: Giving voice to Indigenous Youth. Pimatisiwin 11: 521–37. [Google Scholar]