2.1. Introducing the Subjects

The setting of this study is a small, mountainous village in the South Peloponnese. Its population, of approximately 1500 inhabitants in the early 20th century, subsisted on pastoralism and agriculture, while many contributed seasonal harvest-related labor in the villages scattered in the nearby fertile plains. Social stratification, emanating from a semi-feudal economic structure, meant that there was a minority of wealthy villagers with lots of acres of land, two-story houses prominent in the village square, enough capital to operate as unofficial usurers and social as well as political power. The rest either worked for other people’s land, cultivated small family-owned plots and vineyards, raised livestock or got involved in the very few available local businesses, mostly taverns, small grocery stores, etc. Almost all had limited access to capital and resorted to onerous loans and mortgages, in order to meet their socio-economic obligations.

Panagiotis was born in 1877 to a poor family. At the age of 22 he migrated to the US and returned a few years later, to get married. With his wife Konstantina, they raised twelve children. Yet their lives were scourged by all those problems encountered by the majority of peasant families; land scarcity forced Panagiotis to work for other people’s land with little return; frequent illnesses took their toll on the family, losing four of their children to tuberculosis; continuous warfare and banditry were the cause of the murder of another two children. The premature death of two of his married daughters—whose husbands had migrated to the US—meant that Panagiotis took under his wings their little orphans, extending the number of dependent members of his destitute household. Panagiotis must have felt despair when he decided to sign another burdensome loan. But even this decision was not the end of his troubles; unable to pay off his debts, having lost all his plots and fearing that his mortgaged house would be next in the line of confiscations, Panagiotis lost his temper and attacked his loaner. The same night, he borrowed money from his father-in-law and took the first boat to New York. According to the Ellis Island records, this second time he was 40 years old, joining a group of other male co-villagers heading to the States. They all went to the same co-patriot to work as bus boys. Later, he took up street-peddling, selling peanuts and cigars in Long Island, New York. From there, Panagiotis remitted money to his family and to the usurers, but also crossed the Atlantic another two times, to join his family left behind.

In one such trip, Panagiotis decided that it was to the benefit of his populous household to take one of his sons with him to the US. Dimitris, or Mitsos, was only 15 then. His narrations to his daughter later in life unfold his comic-tragic passing of the Atlantic, overcoming the suspicion and scrutiny of the authorities, that forbade the migration of males near the age of conscription. Upon arrival, Mitsos was entrusted by his father to a fellow villager who owned a flower shop. Just a few months later, Mitsos—who loved a job that brought him close to nature and his village roots—felt talented and experienced enough to open his own florist store in the Bronx. A few years later, he was a successful businessman, by then called James or Jimmy; he married a Greek girl, Maria, and had three children. Mitsos worked hard without any help; he even delivered flowers on his own, using the subway. Throughout his life he made efforts to connect with his past. Not only did he give his dead sister’s name to his daughter, but he also kept writing letters to his family in Greece, dispatching items and remittances. Later in life, Mitsos’ decision to invest his saved money in buying a farm-hotel from a fellow Greek brought the family close to bankruptcy, and it was at that point that his wife expressed her opposition to supporting his family back home. His economic difficulties, along with the fact that he never had a business partner that would allow him to take some time off to travel, contributed to the fact that Mitsos never returned to his home village. According to what he told his daughter, it was his mother’s death that made him lose any interest in ever returning to Greece.

In the same village, another man named Panagiotis, along with his brother Nickos, decided to migrate to New York, in search of a better future. Panagiotis, whose first departure was in 1899, took up street-peddling, selling apples on Brooklyn Bridge. Nickos, or Nickolakis (small Nickos), first departed in 1905 to join his brother; Nickolakis got his own basket, selling peanuts next to Panagiotis. While Nickolakis migrated after his marriage, Panagiotis returned to Greece to get married and then headed back to America. Panagiotis was soon joined by his first-born son Antonis in 1911 and then Giorgos in 1916, who traveled with a group of male compatriots as “workmen”. Antonis, Giorgos and Nick opened a family luncheonette, called Rivoli Sweetshop in Long Island. The families lived in small apartments overlooking their business. Antonis married a German migrant woman and had a daughter. Giorgos married a girl from his village and had two sons. Nickolakis kept travelling back and forth to the United States, to the point where fellow villagers shared anecdotal stories mocking his frivolous journeys. In one of his return trips Nickolakis also took with him his 14-year-old daughter Kalomoira, whose marriage to Nickolakis’ Greek-born business partner had already been arranged. Both Panagiotis and Nickolakis kept remitting money and commodities back home throughout their stay in the United States.

2.2. Theoretical Context

Transnationalism is a term used by academics in various fields to describe the in-betweenness in peoples’ actions, practices, personal and collective identifications and conceptualizations across borders. Its growing popularity throughout the 1990s and early 2000s had a strong methodological and conceptual impact on migration studies in particular. Inextricably linked with mobility, transnationalism was recruited to explore the ways in which migrants, individually or in groups, made sense of their experience and the worlds surrounding them—how they lived, acted and felt, but also how they identified themselves individually or collectively. Ever since the pivotal work of Basch, Glick-Schiller and Szanton-Blanc (

Basch et al. [1994] 2004), numerous studies have contributed to the “transnational” viewing of different diasporic communities across the globe, with parallel academic debates challenging the concepts of nationhood and ethnicity, or the essence of identity.

Far from attempting here an overview of the existing multi-disciplinary literature on transnationalism—which is beyond the scope of this paper—it is worth-noting that the full-fledged blossoming of this term is also surrounded by ongoing debates. As Steven Vertovec points out, “the ‘what’s old/new’ question is but one of a number of doubts or criticisms that have challenged the transnational turn in migration studies”. (

Vertovec 2009, p. 16) The close association of globalization and technology with migration often led to the assumption that transnationalism was another manifestation of the globalized, mediatic late 20th century. The critics of such assertion were mostly historians, insisting that transnationalism is not new by tracing evidence among early migrant communities worldwide. Another criticism centers on the omnipresence of transnationalism as an analytical tool or its treatment as a panacea in methodological and interpretational grounds. This matter is further complicated by the use of terms such as translocal, international and global as interchangeable. Not all migrants were transnational, and it is thus necessary to further explore similar terms in the palette of migrant studies.

Placing this paper on the map of transnational approaches to migratory phenomena inescapably begins with emphasizing “the oldness” of the term, as a way to approach the early 20th century migrants described here. The innovative work of Ioanna Laliotou (

Laliotou 2004) concerning early migrant communities of Greeks in the United States has always been an insightful source of inspiration. Transnationalism in this paper is viewed as a “normal dimension of life”, as described by Donna Gabaccia (

Gabaccia 2000, p. 11), yet the effort is placed in demonstrating its distinct characteristics in relation to the particular ethnic group, but also to the individuals’ experiences. Focusing on micro-history and personal memorabilia enables the exploration of transnationalism as a lived experience with individual variations. For example, while some migrants travel back and forth continuously—a characteristic of “old transnationalism”, according to Vertovec (

Vertovec 2009, p. 14)—others never repatriate, and while some young women migrate alone, others face the hardships of being the “wives left behind”. Transnationalism is emphasized as a constituent of individual and collective identities—such as family—yet in varying degrees and in different forms.

Another assumption permeating this work is that transnationalism is a holistic tool that cannot be pinpointed in one particular area or discussed through problematic dichotomies. Rather, transnationalism is acted, felt, verbalized, conceived and imagined. The study of transnational subjectivities, by exploring their own voices and cultural activities, as manifested in letters, photographs and items, allows us to draw nearer to individuals’ thoughts, emotions and practices. Transnationalism concern bodies that travel, that dress up in fashionable attires and that pose in a studio as much as it concerns hearts that experience pain, nostalgia or guilt. Focusing on the cultural aspect, like Maruška

Svašek (

2012),

Laliotou (

2004) and many others, we unravel a world of practices, emotions and ideas, that constitute the personal and holistic fabric of transnationalism.

Finally, though literature concerning migrants’ transnational existence is extensive, less emphasis is placed on the ways in which transnationalism affected those left behind. Magnifying the individual spectrum to that of the family group can shed light on how remitted capital was invested back home, on how the access to the “American dream” was “capitalized” in the marital market of the homeland, on what it meant for a left-behind wife to work the family land, or what emotional management was required in both sides of the Atlantic. Here, the works of Linda Reeder (

Reeder 2003) and Caroline

Brettell (

1987) are highly elucidating in understanding the ways in which transnationalism not only affected the countries where migrants arrived, but also their homelands.

For the purpose of this study, I focus on a body of letters, photographs and financial and judicial transcripts belonging to, or exchanged between, two dispersed households. This material was initially collected through fieldwork in Greece and the United States and analyzed in the context of my dissertation.

1 Here, my approach is more micro and focuses on a specific aspect of the Greek transatlantic movement: transnational families. Being a descendant of these families myself, I have first-hand information concerning the subjects, deriving from their children, grand-children and nephews. Victoria, Mitsos’ daughter, has provided me with detailed explanations and stories about her father, along with access to her father’s photographs accompanied by her own explanatory narratives. Mitsos’ five letters analyzed here belonged to my late father. Giorgos’ letters, along with all financial transcripts and judicial records (64 in total), were given to me by his nephew George, who has also provided me with meticulous explanations on the family history. All other photographs discussed in this work belonged to my late father and now constitute my own private collection. Letters were saved by the Greek side of the family in both cases. Photographs were also sent by migrants to their families in Greece, which were taken, with few exceptions, by members of the family in Greece.

Without a concrete method of approach—other than treating both letters and photographs as “texts”—I mostly relied on gathered information concerning the subjects as well as existing literature focusing on migrant groups and their cultural production. Migrant letters have received significant attention in the past few years, with some studies “letting the source speak for itself” with some contextualization—such as Alan Conway’s work on the Welsh in America (

Conway 1961), Ruth Cape’s study of a German migrant family in Texas (

Cape 2014), H. Arnold Barton’s work on Swedes’ epistles from America (

Barton [1975] 2000), Kerby Miller et al.’s study of Irish migrant letters (

Miller et al. 2003), Wendy Cameron et al.’s work on English immigrant voices in Canada (

Cameron et al. 2000), Samuel L. Bailey and Franco Ramella’s analysis of an Italian family’s correspondence between Italy and Argentina (

Bailey and Ramella 1998), and others providing an extensive analysis and contextualization of such texts, or discussing them in thematic sections extending to various ethnic groups, such as the works of Sonia Cancian on Italian migrants in Canada (

Cancian 2010), David Gerber’s on British migrants (

Gerber 2006) and Bruce S. Elliott et al.’s collective work (

Elliott et al. 2006) on migrant letter practices among different migrant groups. Theoretical works on correspondence and epistolary practices have also been looked at, in the works of Janet

Gurkin-Altman (

1982), Cécile

Dauphin et al. (

1995), Roger

Chartier (

1991) and Yves

Frenette et al. (

2006). It is worth noting here that, to my knowledge, there has been no published scholarly analysis of letters written by Greek migrants to the United States.

2 For the case of photographs, I mostly relied on works focusing on the medium itself, and most importantly on the use of photographs as narratives, as sources of valuable historical and anthropological information. Here, the works of Jon

Prosser (

1998), Pierre

Bourdieu (

1996), Karen

Strassler (

2010), Julia

Hirsch (

1981) and Annette Kuhn (

Kuhn [1995] 2007) have significantly aided my approach. It should be added that, to handle such diverse material, interdisciplinarity ranging from history to social and visual anthropology and media studies is undoubtedly a sine qua non approach. I should further note that all letters were written in Greek, and thus all translations are mine. I tried to stay close to the migrants’ prose, despite its mistakes, some of which—spelling, in particular—were lost in translation.

2.3. “We Are Healthy and Hope the Same for You”: Health and Death Across Borders

Migration signified the passage from oral to written communication for the young migrants studied in this article and their transnational kin. Staying connected with family and friends back home meant the dispatching and receiving of letters, usually accompanied by photographs placed in the same envelope. “Epistolary language is preoccupied with immediacy, with presence, because it is a product of absence” (

Gurkin-Altman 1982, p. 135). This absence, this experienced gap, generated concern and uncertainty in both sides of the Atlantic. Good health was the prime condition fomenting the hope for a future union, the bridging of the gap, the refutation of absence. Questions about health at the introduction of each letter were formulaic and repetitive, written in “kathareuvousa”

3, in a way that often contrasted with the poor prose that ensued. Written by people who were semi-literate and unaccustomed to written communication, letters were manifestations of their strong desire to stay connected, which made them overcome their limited skills in actually composing an epistle. “My dear brother Marini, we are healthy and hope that you are all healthy too”, wrote Mitsos to his brother in Greece, in a formulaic, archaic-Greek prose (

Mitsos 1946b).

Some deviations from the standard formulaic health questions, though, were also present. As Sonia Cancian points out, the nature of the relationship between the writers is often reflected in these formulaic expressions (

Cancian 2010, p. 44), with more detailed references shared among more intimate kin members. When Mitsos wrote to his father, who seems to be his closest family, he went beyond the typical Greek epistolary introduction: “My dear father … this winter has been really bad. Our little one has gotten sick with his kidneys too many times yet thank God, he is ok now” (

Mitsos n.d.). Moreover, allegiance to the extended kin made letter-writers expand their intended audience beyond the official recipient of their letter, by addressing health questions to various kin members, even neighbors and friends. Accustomed to verbal communication, letter-writers extended such questions in second singular person, as if speaking to them directly, even though one could assume that letter-writers expected their letter to be read by all kin collectively and thus formulated questions accordingly.

To attest their safe arrival and good health, early migrants also felt the urge to have their picture taken and dispatched to their relatives abroad, along with their letters. This “first picture” served as the witness of their safe passage, but also of their eminent change. Mitsos seems to have visited a studio, “with its choice of painted backgrounds and plaster pillars” (

Hirsch 1981, p. 43), to pose for a photograph sent to his mother in Greece. His attire, subtle smile, in-fashion hairstyle and frontal posture reveal confidence, expected success, but most importantly reassurance; he was there; well, safe and successful for the mother to see. (

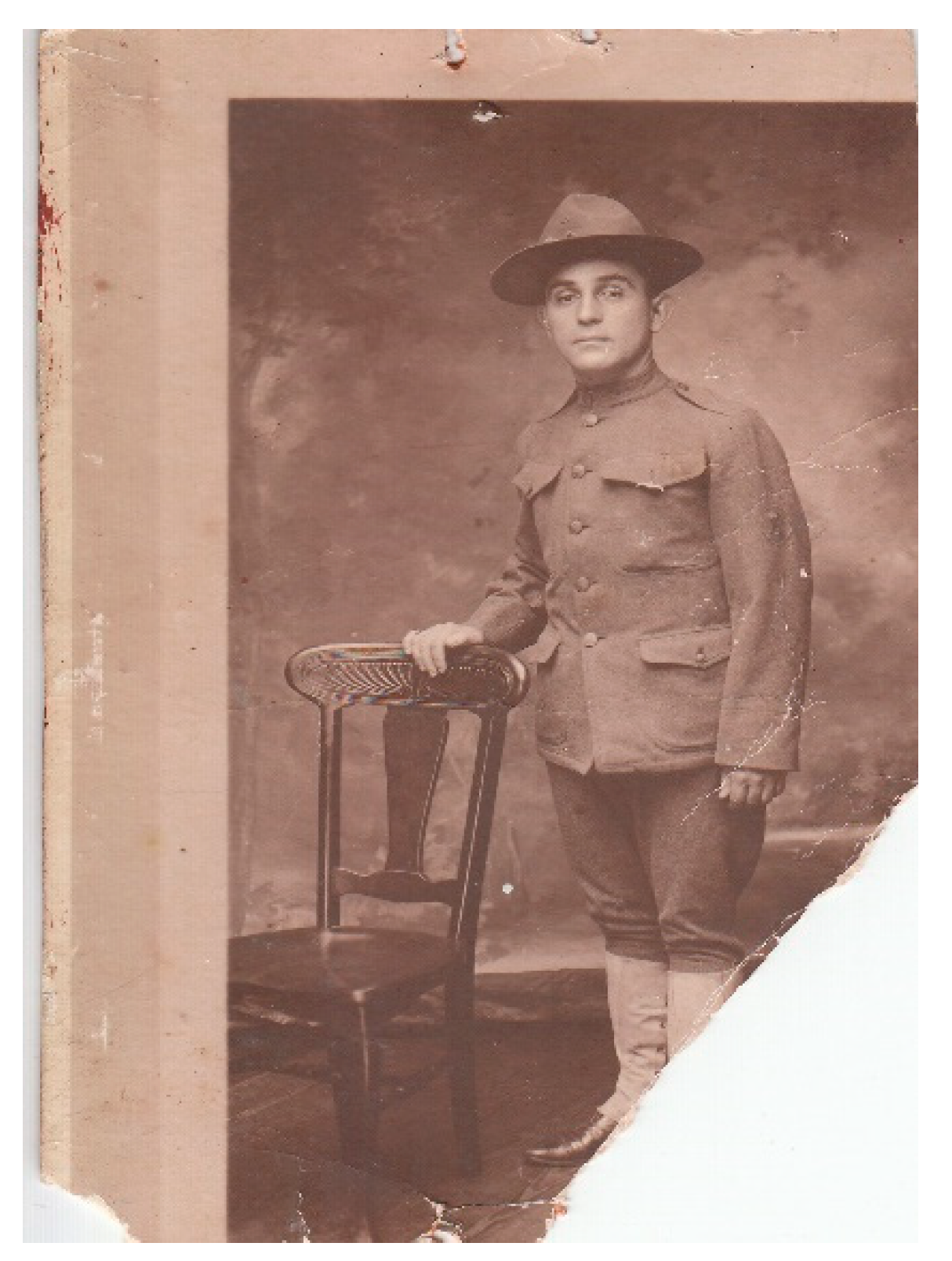

Figure 1) Still a member of his family back home, his appearance in the photo also reflected change. This young Greek adolescent left his loom-made shorts behind and transformed into a well-dressed working man in a suit and a straw hat borrowed to the studio. Nickolakis went a step further in reporting change, by posing for his first photo sent home in an army uniform. This attire was most likely rented, as he could not have served in the US army without US citizenship. (

Figure 2).

Satisfaction over receiving a letter or a photo, or complaints over the frequency of exchange were also reported. “It’s been very long since I last received a letter from the village and I don’t know how you are all doing” complained Mitsos (

Mitsos 1946a). As Fitzpatrick emphasizes “the arrival of a letter was in itself a token of solidarity, while the absence of an expected letter was an endemic source of anxiety, even a harbinger of death”. (

Fitzpatrick 2006, p. 97). Yet news of death and the pain these emanate were inescapable; migrants felt guilt for not being there and sorrow for experiencing the loss alone. Mitsos found out about his sister’s murder and wrote to his brother: “I feel so much pain for our sister Eleni’s death. Now that we could help her a bit more, we lost her” (

Mitsos 1946b). In a very lyrical tone, Giorgos wrote to his brother and mother in Greece, after being informed of his father’s death. He decorated the letter with little crosses, to manifest his utter grief: “we received the sad and bitter letter and were deeply saddened. The death of our beloved Father has given us great grief, to us, our kin and our compatriots [here in the US] … Mother, I hope that God keeps you strong and consoles you because we lost a good and respected father, good for all the family … even if I wanted to write more I could not because my eyes are filled with tears … may God forgive us for being away from home, from our parents and kin who die and we cannot even see them”. (

Giorgos 1938).

In an effort to overcome spatial and temporal distance, migration and death, Fyllio, Mitsos’ black-wearing sister visited a flaneur photographer in the village with various portraits of family members; some in the United States, some in Australia, some deceased, most never having met or coincided. Her commission was clear: to collage, to put them all together in one photo of this transnational family that was hanging on her parlor wall throughout her life, dismantling temporal and spatial barriers (

Figure 3). The central figure is her mother Konstantina, holding a child. It was her passing that made Mitsos lose interest in returning to Greece one day.

It is thus evident that migrants and their kin utilized letters and photos to replenish the spatial gap caused by migration and mobility. Questions about health in their letters and photo-testimonies of their safe arrival and well-being exhibited the prime concern and ultimate desire of dispersed transnational families: health and well-being were the most basic pre-conditions for undisrupted family unity and potential future reunions. Yet at the same time letters and photos contained evidence of the undergoing and unstoppable change caused by migration and mobility. This change did not only concern migrant attire, but most importantly the very nature of transnational family relations. Communication was no longer verbal and direct but written and fractured in long temporal intervals. Emotions such as pain and grief were not experienced in the company of kin, but rather in the tormented migrants’ hearts and minds, when a loved father passed away and they were not there for farewell. Familial unity, as it existed before migration, had received its first blow.

2.4. “I Enclose a Cheque for You and Another One after Mother’s Day”: Remittances, Checks and Debts as Household Strategies

Economic motives have long been held as the prime reason leading Greek migrants—among others—to the shores of the New World. In the context of a “household strategy”, families invested in the migration of young and agile members, to promote family goals—primarily paying off debts, disengaging mortgaged houses and plots, amassing trousseaus for young daughters, buying houses and land, financing a local business or a sibling’s educational endeavors. When Nickolakis migrated to the United States, he kept remitting checks to his wife Maroula, whose two sisters were “American brides”. Upon his return, not only did he manage to buy land in the village, but also invested in acquiring an apartment as dowry for each of his daughters in the urban port of Piraeus, in Greece.

When Panagiotis departed in the late 19th century, the extensive family records reveal that he had received six loans with a 9% interest and had two houses—that were given to him as dowry from his wife’s family—as well as two major plots of land confiscated by his usurers, as a consequence of his inability to pay off. In 1916, he decided to return to the village, only to find himself indebted once more; this time, twelve loans in less than twenty years. Creditors exerted pressure, leading him to join his sons in New York once more. In 1915 Eleni, the wife he left behind, signed the following document: “Loan Payoff: On December 14, 1915, I received by the debtor Eleni, a housewife, whose husband is an immigrant in the US, 600 drachmas with interest. I therefore consider the loan fully paid off”. The inability to pay off loans also burdened women left behind, who saw charges pressed against them, in the absence of their male counterparts. In 1939, Eleni and her two migrant sons were convicted in absentia by the Greek court, demanding the return of 8508 drachmas to the usurer, Mr. V. On December of the following year, Eleni found the following notice affixed to her door: “I, Ioannis V., demand immediately from Eleni D. the reimbursement of a total of 10,825 drachmas with interest, expedition fees and court fees included”. (Archive: Courtesy of George D.).

For currency-deprived households, money remitted by distant kin, contributed greatly to satisfying family needs in the village and financing family plans; it also placed the transnational family in a better position in comparison to co-villagers who had no kin abroad and thus no incoming dollars; better clothing, higher-quality food (usually counted by the frequency of meat consumption), promising dowries, pursuing of education for the younger ones. Mitsos decided to support his orphaned nephew and niece who studied in the local school and wrote to his kin in the village: “I had a letter from our niece Margarita, but I have not received a reply from Niko. I sent him 30 dollars in April and I hope that he received them” (

Mitsos 1946b). In his efforts to support his brother’s poor family, Mitsos wrote in formal Greek: “Dear brother, enclosed, you should find a check of 40 dollars. I had sent you another one, of 30 dollars, and I hope that you received it” (

Mitsos 1946a).

Economic help was perceived by both migrants and their distant kin as a fulfillment of an often unspoken obligation. As Bailey and Ramella point out, “the departure of children barely more than adolescents from a paternal home was not an unusual event … nevertheless, the separation did not exempt the children from their obligations to parents” (

Bailey and Ramella 1998, p. 12). Giorgos, Antonis and Mitsos expressed their desire to meet their parents’ financial expectations in all of their letters to them. They even felt compelled to apologize when found unable to deliver a promised “help”. In fact, such inability was always attributed to declining business profit, leaving no room for doubt over their own loyalty to the transnational family. Writing to his father, Mitsos explained “only now I am doing ok [he refers to his florist store]. Flowers were expensive to buy and since Easter, I have been selling for nothing … I wanted to help but things were not good. Next month I hope that after mother’s day I will be able to send something … to Yannis (his brother) too”. (

Mitsos n.d.). Giorgos wrote to his mother “our mind is always set on helping you…but this winter our business has been too quiet. Now that summer is reaching we hope that our store will pick up yet, my respected mother, we need your help too. Send us your blessing to succeed, for us to be able to always help you” (

Giorgos 1939).

In this effort to assist their kin, news about their business endeavors, partnerships and overall success were always referenced in letters, usually accompanied by “progress report” photographs. Mitsos proudly posed in front of his florist store in formal attire (

Figure 4), while Antonis and Giorgos sent photographs to their parents and uncles, depicting them and their new business partners from the same village. Wearing suits, ties, polished shoes and jewelry showcased their purported success, while their partnership deal is reflected in the shot-captured hand-shake. (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

Transatlantic transnational families could be viewed in the broader context of “household strategy”, with the migration of youngsters viewed as a “good economic decision to support family back home” (

Baldassar 2008, p. 249). With few exceptions, young men were expected to work and thrive, while young women—less frequent migrants in that period—were expected, as analyzed below, to marry Greeks and procreate. Husbands were expected to work and eventually return once family obligations were fulfilled. It seems that gender and age played a significant role in the handling of family needs, with the young first-born sons primarily burdened by the “duty” of helping the family with their migration. This fact is typical of many other family groups around Europe as well as other parts of the world during those times. Migration and mobility were handled by transnational families in ways that showed an adaptive mind and practice: sending their children to America was part of their household strategy, yet the impact of such decision-making varied among the different members of dispersed households.

2.5. “Thank You for the Knitted Blanket We Received”: Gifts, Commodities and Proxy Presence

Upon entering Fyllio’s main room, or “the good room” where she received guests, one could admire the collection of “American objects” dispatched over the years by her father-in-law, Nickolakis. Vases and pots of fine china, heavily ornamented tea-sets, a radio, a mechanized coffee grinder and many other items of little or unknown use to poor villages all signaled Nickolakis’ attempts at social progress and upward mobility. With less frequency, objects from the village also headed to migrant households, especially as “sentimental gifts sent to mark a life-course event or simply because a courier was travelling in that direction”, as Cancian points out. (

Cancian 2010, p. 48).

In a letter to his brother, Mitsos wrote “I have sent you through the “Relief” 4 parcels and I will send you another one. Please find enclosed, the receipt. I have sent you three sacks of flour, and another four for our brother Ioannis, and once you are called by the company to pick them up, write to me right away, tell me if it is of good quality. Tomorrow I have another parcel ready for you, with a coat and shoes and dresses the coat is too big for you so give it to anyone who may need it and the dresses, give them to any female kin you think is suitable and also I have put three bags of rice, one sack of sugar, coffee, pasta and milk for your family and for our mother” (

Mitsos 1946a). In another letter, he mentioned “I have sent many parcels with the war relief, with shoes and clothing, two pairs of boots 7 ½ and 8, an outfit some shirts, pants, sugar, coffee and milk, lots of cans of milk, if it is useful for the little ones write to me so that I send you more and for clothing too even though it is difficult here, there is shortage here as well … for our mother I have sent her black cloth to make dresses and new shoes and to our sister Irene I sent her parcels yesterday and I also included a pair of shoes for the mother and clothing weighting 40 pounds which should be 13 okas in Greek”. (

Mitsos 1946b) It is interesting to note how Mitsos converted pounds to okas, to make the amount comprehensible for his distant kin, yet failed to convert the American shoe-size standard for the boots to its European equivalent—another manifestation of his here-and-there existence.

Objects from America, especially in moments of crisis, as WWII and the ensuing Greek civil war, served primarily to satisfy the material needs of destitute peasant households. Yet as Cecile Dauphin et al. stress, the demand for, and exchange of, objects exceeded material needs and aimed mostly at reinforcing family relations and family cohesion across borders. (

Dauphin et al. 1995, p. 171). Inasmuch as family unity is projected in such flow, division also emerges; objects from America served as metaphors of material affluence and prosperity, in sharp contrast to the precariousness, scarcity and material deprivation encountered in the homeland. When Mitsos sent his family a mule in the tormented 1940s, its red hair and astonishing size, gave the animal its name: “the American”. On the other hand, gifts sent by peasant families to their migrant kin aimed at a positive re-interpretation of such division. Far from corroborating material scantiness, they shifted emphasis on their “originality”, “hand-work”, “purity” and “tradition”, in contrast with ample, massively-manufactured, “modern” “American” goods; a food made by female kin using ingredients picked up by the family plot, a hand-knitted elaborate blanket to celebrate a migrant’s marriage or the birth of a child. Giorgos wrote to his mother and brother: “please thank my sister-in-law for the beautiful blanket she made for our little baby son. It is truly very beautiful” (

Giorgos 1939), the result of personal skills, family effort and Greek tradition.

The sending and receiving of objects has been a common practice among transnational households throughout the years. Such exchanges constituted the “symbolic and material enactments of transnational family relationships” (

Basch et al. [1994] 2004, pp. 83–84), with the frequency and the number of people participating in such exchange alluding to the very perception of family itself. Requests for objects often corresponded to actual material needs, but most importantly confirmed the “proxy presence” of migrants and their kin in each other’s lives. Their tangibility transformed them into “memory triggers representing the longed for kin and the emotion of missing them.” (

Baldassar 2008, p. 257) It can thus be assumed that items exchanged between dispersed kin were not only destined to quench actual practical needs but also, and most importantly, aimed at invigorating kin ties at a distance, at maintaining the channels of communication, loyalty and affect.

2.6. “We Miss You”: Emotions, Memories and Return Visits

Transnational families visualized themselves not only discursively or practically but also in terms of emotional belonging. The interest in emotions in the context of migration has gained ground in the last few years, with studies focusing on the affective ties of migrants and their homeland and/or their loved ones.

4 Emotions mandated by external conditions—in this case separation—but also harnessed by cultural norms, were seldom articulated in the letters of migrants and their distant kin for various reasons. Some, like love for the family, were often taken for granted, while others, like loneliness, could be deemed as signs of weakness, especially those pertaining to Greek gender stereotypes of the time. Patriarchal strictures, on one hand, and unquestionable respect for the elderly, on the other, harnessed the behaviors and relations among spouses, siblings and other kin ties.

5 This may be the reason why the under-represented female voices were more likely to allow themselves emotional utterances, or to request emotional reassurance by the recipients of their letters. Responding to the attributed sensitivity of women’s emotional landscape, Giorgos wrote to his mother “my dear mother, for you to forget your sorrow, you have to come to America for a trip. We hope to be able to send you your trip expenses, so that you come to America, to see your children and your grandchildren”. (

Giorgos 1939) Missing kin is considered to be the prime reason for emotional suffering, which can only be “managed” by effectuating a temporary re-unification of the transnational family.

The absence of emotional expressions can also be attributed to the unfamiliarity with such endoscopic confessions; affective voicing was not common among peasant communities of the early 20th century.

6 Husbands and wives, children and parents, siblings and in-laws formally addressed each other, mostly governed by feelings of respect, if not fear in certain cases. Allowing emotional gusts, though reassuring of family unity, could be interpreted as a deviation from familial emotional rules, but most importantly from Greek cultural norms about emotional management. As in the homeland, migrants and their kin unraveled their emotions in moments when it was “right” and “expected” to do so: crisis, sickness and death. Giorgos’ writing was blurred by his shedding of tears, admittedly unstoppable, in his letter concerning his father’s death. Unleashing his grief and pain in words consoled his deeper guilt: “our parents die and we cannot even see them”. As Susan Matt puts it “there was a trauma associated with migration” (

Matt 2011, p. 3) that was hard to heal.

Emotions and memories are also intertwined in the hearts and minds of migrants and their distant kin. Memories of home and of the loved ones evoked emotions like nostalgia and longing. On the other hand, emotions triggered memories, fostered visualization, urged subjects into “taking action” in sustaining transnational family links. Exchanging letters and, most importantly, photographs not only “made up for the failures of memory” (

Bourdieu 1996, p. 14), but also served to provide transnational families with “surrogates or visual reports of people separated by time and space”. (

Musello 1979, p. 113) When migrant kin posed together (

Figure 7) in a studio and sent their portraits to their extended kin back home, they not only fought against oblivion, but also pointed at their current, best and decisively changed image. The exchange, viewing or reading and display of family photos and letters allowed people to accept the distance between them and the otherwise unwitnessed change they underwent and to hope for a reunion someday. “To not forget me”, wrote Olga to her sister and brother-in-law, Maria and Nickolakis, when sending a picture of her posing in a New York studio (

Figure 8).

In order “not to be forgotten”, Olga visited her sisters in the village several times, for her summer holiday. It was her way of maintaining familial bonds and contact with the homeland, but also of “vacationing”, in a way that was unknown to her kin in Greece. Received by the family (

Figure 9), she sojourned in her sisters’ homes and paid visits to all her extended family in the village, bringing countless bottles of creams and perfumes as gifts for her female kin. Contrary to the popular belief that migration meant permanent separation and thus generated sheer pain, the sources utilized for this article show that this was seldom the case. Mitsos’ definite departure stands out as unique in relation to all other migrants discussed here. Giorgos and Antonis, on the other hand, were among those who crossed the Atlantic various times to re-join their family and village community. In a photograph (

Figure 10) taken in the village school-yard, the teachers and school-children had organized a feast to celebrate the arrival of migrants. Antonis posed with his Ahepa (American-Hellenic Educational Progressive Association—most Greek migrants of the time eagerly joined this organization as a way to maintain their Greekness) attire and hat, accompanied by other migrants, who enjoyed the dancing of traditional dances by students dressed in the Greek national costume. Panagiotis and Nickolakis also paid many visits to their homeland until they eventually resettled, approximately a year before the breakout of WWII. Crossing the Atlantic not only served to maintain transnational links, but also pointed at a generation of early migrants, who were unintimidated by embracing the technological advances of modernity and travelling back and forth.

Missing, longing and nostalgia were emotions commonly experienced by migrants and their kin. Even when emotional responses were unwelcome by the Greek feeling rules or the “proper” familial hierarchies of the time, they were never fully concealed. Especially in moments of crisis, emotions stormed out of people’s hearts, and words and such utterances not only served to reassure familial bonds of affect, but also enabled subjects to deal with pain and separation. As Baldassar suggests, longing and missing people and places “manifested in four key ways: discursively and physically as well as through actions and imagination” (

Baldassar 2008, p. 250). Therefore, nostalgia was not only “confessed” in letters, but also alleviated by the sending of letters and items to secure a proxy presence—as seen in previous sections—by imagining a family reunion—as was the case of Giorgos and Antonis hoping to bring their mother to the US—and, most importantly, by visiting the homeland and the loved ones.

2.7. “I Have Asked My Brother to Take the Best Care of You”: Brides, Migrants and Wives Left Behind

A hand-written village record [author’s collection] dating from 1932 reveals that migrants since 1898 amounted to 298 out of a population of approximately 1000 people. Of them, single males doubled those married, yet 1/7 were children, aged between 5–17 years old, who travelled in groups of peers or accompanied by their fathers. With husbands and sons abroad, a number of women found themselves left behind, usually surrounded by younger children, especially daughters. In the early years of migration, only a few dozen of these wives opted for joining their husbands, along with their young offspring. The majority deemed their husbands’ migration as temporary and decided to stay. It was the case of Eleni, the wife of Panagiotis and mother of George and Antonis, and Maroula, the wife of Nickolakis and daughter of Michael, also a migrant in New York since 1904.

Missing their husbands and sons was devastating, yet not the sole difficulty of living in the absence of men. Wives left behind assumed the roles and responsibilities of their male counterparts, to the degree that this was possible, given the stringent patriarchal village context. Remitted money usually secured economic amelioration, yet as sources manifest, the prime familial goal was the payment of creditors, the purchase of a house or plot of land, the education of children and the amassing of dowries for unmarried daughters. Little was left for daily spending, or for relieving women from contributing arduous farm labor for familial subsistence needs. Migrants’ wives, though, preferred to work for their own family rather than take paid labor in other farms, as a symbolic manifestation of their social upgrading due to migration. As a left-behind wife, Eleni was in charge of paying off usurers, for the loans that her migrant husband had signed prior to his departure. She must have experienced tremendous stress when, in certain cases, she found court appeals pinned on her door, due to her inability to meet financial obligations. Both Maroula and Eleni were further burdened by the need to work the family land—a physically demanding endeavor—assisted only by their sisters and younger children. In 1908, another court call came for Eleni, when her neighbor in the gardens stated the following: “since early August 1908 the defendant’s [Eleni D] pig has consecutively invaded my gardens and has eaten and uprooted with its long nose all my potatoes and zucchini, of a total value of 25 drachmas. I call the defendant [Eleni D] to court and demand that she pays the aforementioned sum as well as all legal costs”. Eleni’s fear of consequences while alone was pacified when she hurriedly reimbursed her neighbor with the whole sum within a few months.

Daughters or sisters of migrants constituted another category of women left behind. The expected dowries they would receive by migrant kin placed them at the top of the local marital market. Prospective grooms were not only interested in these brides’ economic potential, but also in the indirect access to the American dream. Potentially, their new in-laws could sponsor their own migration to the US. On the other hand, though, the absence of male vigilance in securing female honor, placed the family reputation in jeopardy: any female action or utterance was scrutinized, as it potentially threatened the transnational family’s social positioning in a patriarchal context. This is the reason why a number of migrants decided to sponsor their sisters’, sisters-in-law’s or daughters’ migration to the US with the purpose of marriage. Besides, by “emigrating to the US, Greek women overcame problems of procuring dowries and problems of finding husbands in home areas where single men were scarce” (

Schultz 1981). This was the case of 14-year old Kalomoira, Nickolakis’ daughter, who passively followed her father to New York, to marry his quite older business partner, only to be widowed and left alone with two young children shortly after (

Figure 11).

Migrants desiring to marry Greek women created a niche for young and aspiring females to cross the Atlantic, with the purpose of marriage. “For the immigrant Greek bachelor who wished to marry, it was customary to return to Greece for an arranged marriage” rightfully comments Schultz (

Schultz 1981, p. 206). In this fashion, Panagiotis, Giorgos and Panagiotis returned to their village, to marry, and, after establishing a conjugal home in Greece, fled again to the US. Only Giorgos brought his bride to New York. If a patrilocally grounded female was not within reach, the second best choice was that of marrying a Greek woman from whichever Greek village, or even a US-born Greek. This was the case of Mitsos, whose wife Maria had been born and brought up in the United States (

Figure 12). Marrying Greeks not only fulfilled the desired cultural pattern of endogamy, but also secured the establishment and participation in what was forming as a Greek community abroad, based on the preservation of Greek language, religion, culture and social reproduction. However, exceptions did exist, with children often breaking this yearned for Greek linearity by embracing American culture, more so than the home-imposed Greek tradition. In the same context, mixed marriages were by and large viewed as “threats”, haunted by the fear of a full assimilation of the migrant and his nuclear family. This was the perceived threat that Antonis sensed when marrying a German woman, which he soon divorced. In fact, when Antonis married this young woman, he avoided writing letters to his family, whose desire for Greek endogamy he felt he had thwarted.

Migrants’ mothers were the last category encountered in this village community. Records reveal that despite the heart-breaking experience of parting with their children, mothers overall supported their sons’ and daughters’ migration. There are cases of migrants whose tickets and journey expenses were covered by their mothers, as sources attest. The emotional weight of the mother-figure on migrant offspring was the most emphatic, with gender expectations attributing more pressure on daughters to care for their mothers. All letters discussed here, however, were written by migrant sons, who also reveal their prime concern over their mothers’ health, emotional state and well-being. Mitsos’ proxy care for his mother is characteristic of his deep devotion to her. Learning that she suffered from vision impairment and that the village lacked a doctor, Mitsos decided to step in: “My dear brother … for our mother’s glasses I visited some ophthalmologists, yet they told me that they need to have a prescription in order to make glasses for her yet I found a friend doctor who promised that he can make glasses according to her age so I told him that mother is 75 years old and he said that he will have them ready. Once I get a hold of them I will send them immediately”. (

Mitsos 1946a) His mother was, in his heart and mind, equated with his homeland. This is why, as he confessed, losing her meant for him losing all interest in returning to Greece one day. In the same frame of mind, Giorgos kept writing words of affection to his “beloved mother”, while assigning hands-on care to his brother Yannis, by writing “our brother Antonis and myself will always be trying our best to please our little mother … already we sent 50 dollars and will continue doing our best for her” (

Giorgos 1939), corroborating the words of Baldassar about Italian migrants: “perceptions about health and well-being of older Italians have been found to be associated with how close they feel they are to their children. (

Baldassar 2008, p. 249).

Female members of transnational households had their own stories to contribute to the migratory narrative. Some were left-behind wives, facing the hardships of bringing up a family with many children and taking care of family property as well as family reputation. But it was not only existing marital union that underwent dramatic changes. As Sinke points out, “currents of international migration altered marriage choices and opportunities dramatically” (

Sinke 2010, p. 17). Daughters or sisters of migrants saw their status increase in the homeland and transatlantic marital markets, as early migrants sought to procure endogamous unions by extending marital invitations to brides from abroad or local men strove for access to migration invitation via in-law networks. Mothering from a distance also acquired a new meaning: though mothers often consented to the migration of their offspring, they not only felt pain for such separation, but also had to face loneliness, as their usually polyphonous households were eventually void of children and grandchildren while they were aging and in need of care. Migration and mobility affected gender roles and relations in various ways, while transnationalism served as the ground for this highly transformative process.