Boosting Traffic Crash Prediction Performance with Ensemble Techniques and Hyperparameter Tuning

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Definition

1.2. Related Works

1.3. Research Gap

1.4. Objective and Contributions

- Simulation-based data collection for crash analysis:

- Feature Selection Using the Extra Trees Classifier:

- Handling Class Imbalance with SMOTE:

- Ensemble Learning for Crash Prediction:

- Hyperparameter Optimization via Grid Search:

1.5. Outline

2. Data Collection and Preparation

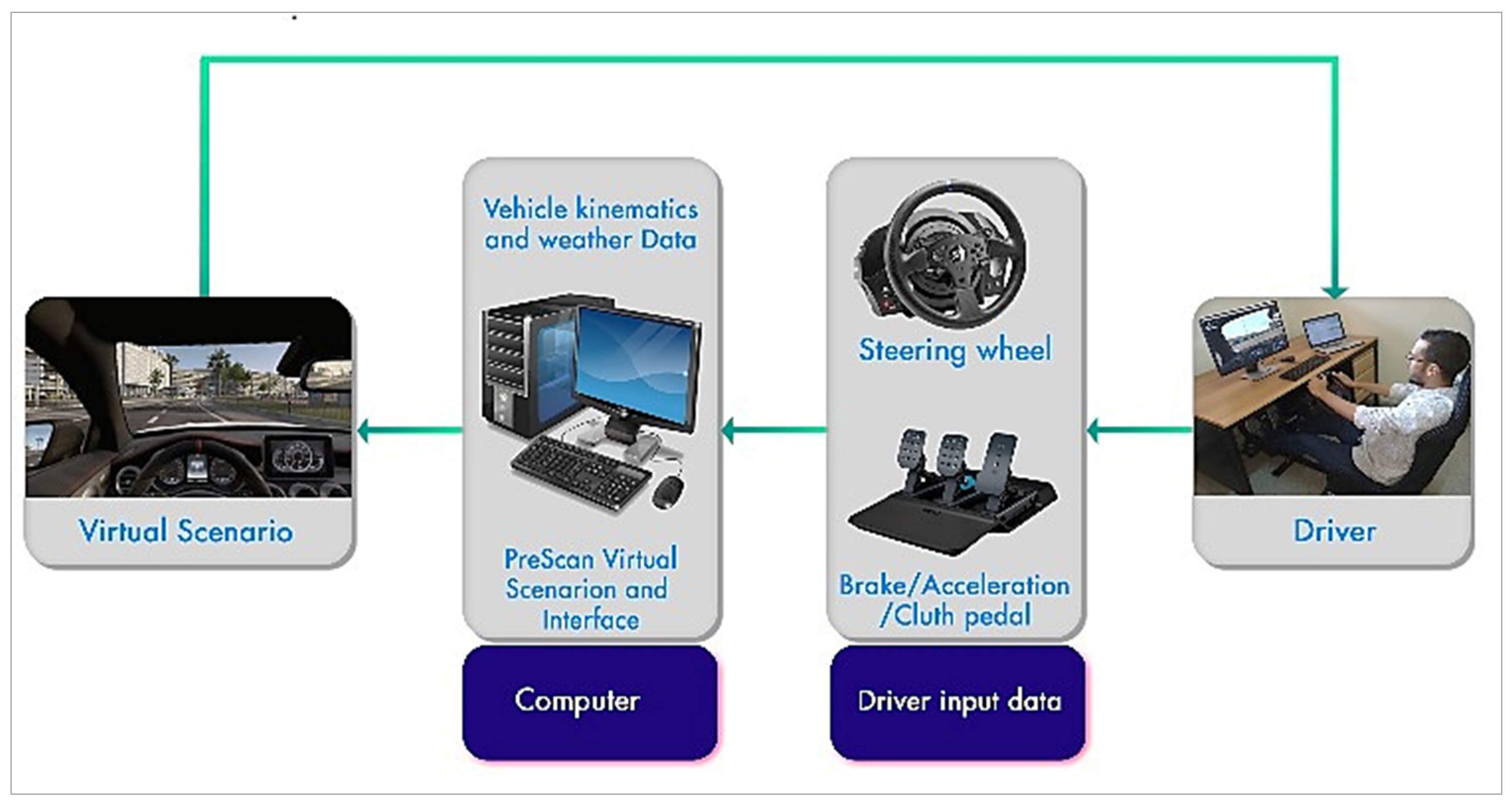

2.1. Driving Simulator

2.2. Scenario and Data Acquisition

2.3. Data Description

2.4. Data Preprocessing

3. Methodology and Experience

3.1. Feature Selection

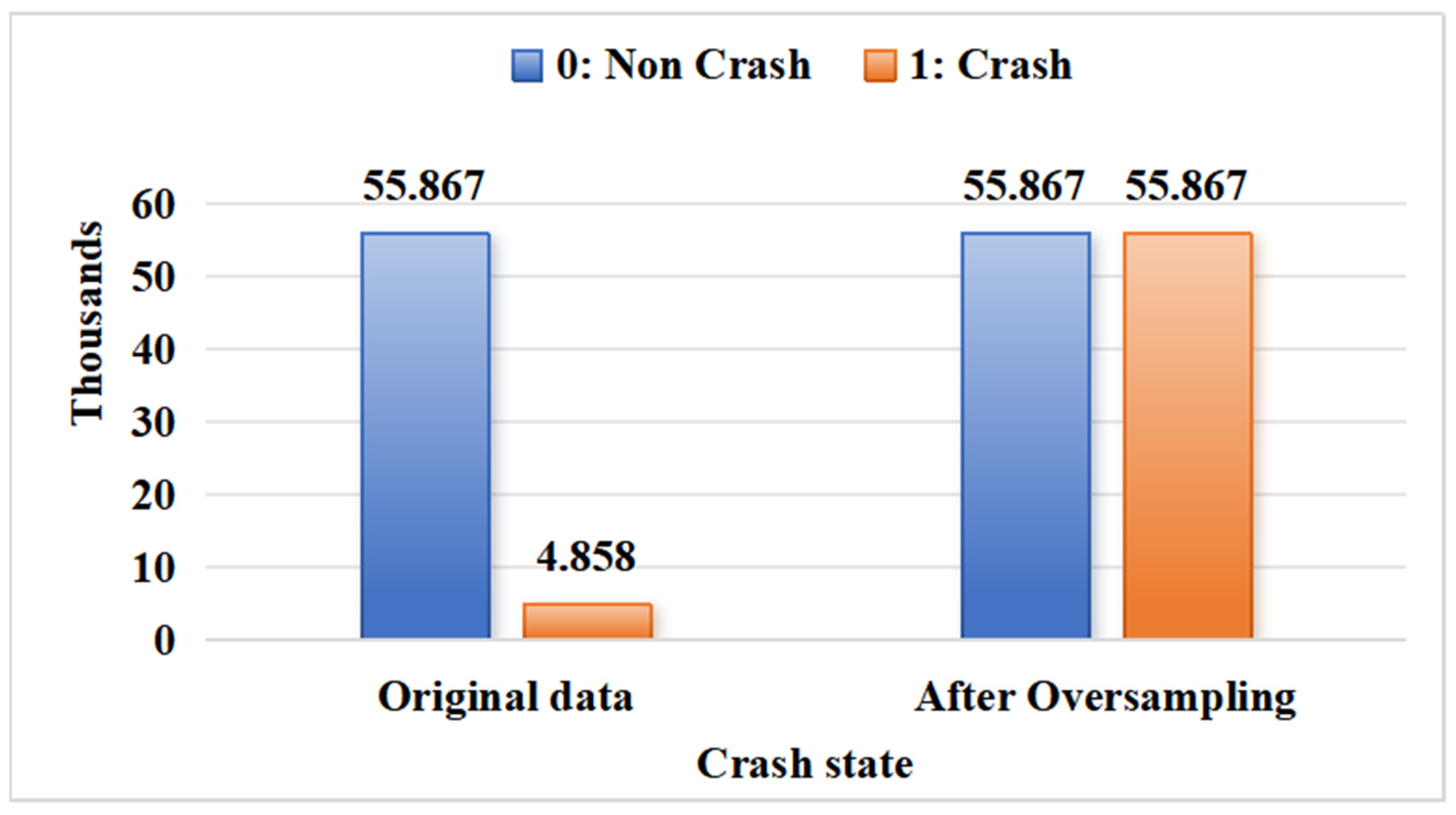

3.2. Data Balancing

- Identify the minority class: Determine which class has fewer instances in the dataset.

- Select a minority instance: Randomly select an instance from the minority class.

- Find nearest neighbors: Identify the k nearest instances to the selected instance. The value of k is specified by the user.

- Generate synthetic instances: Create new synthetic instances by linearly interpolating feature values between the selected instance and its neighbors. This introduces new instances into the minority class feature space.

- Repeat: Continue this process until the desired class balance is achieved.

3.3. Traffic Crash Prediction Models

3.3.1. Random Forest

3.3.2. Bagging

3.3.3. Extreme Gradient Boosting

3.3.4. Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM)

3.4. Hyperparameters Optimization

3.4.1. Hyperparameter Tuning Techniques

3.4.2. Grid Search Algorithm

3.5. Validation Strategy

3.6. Performance Evaluation

4. Experimental Results

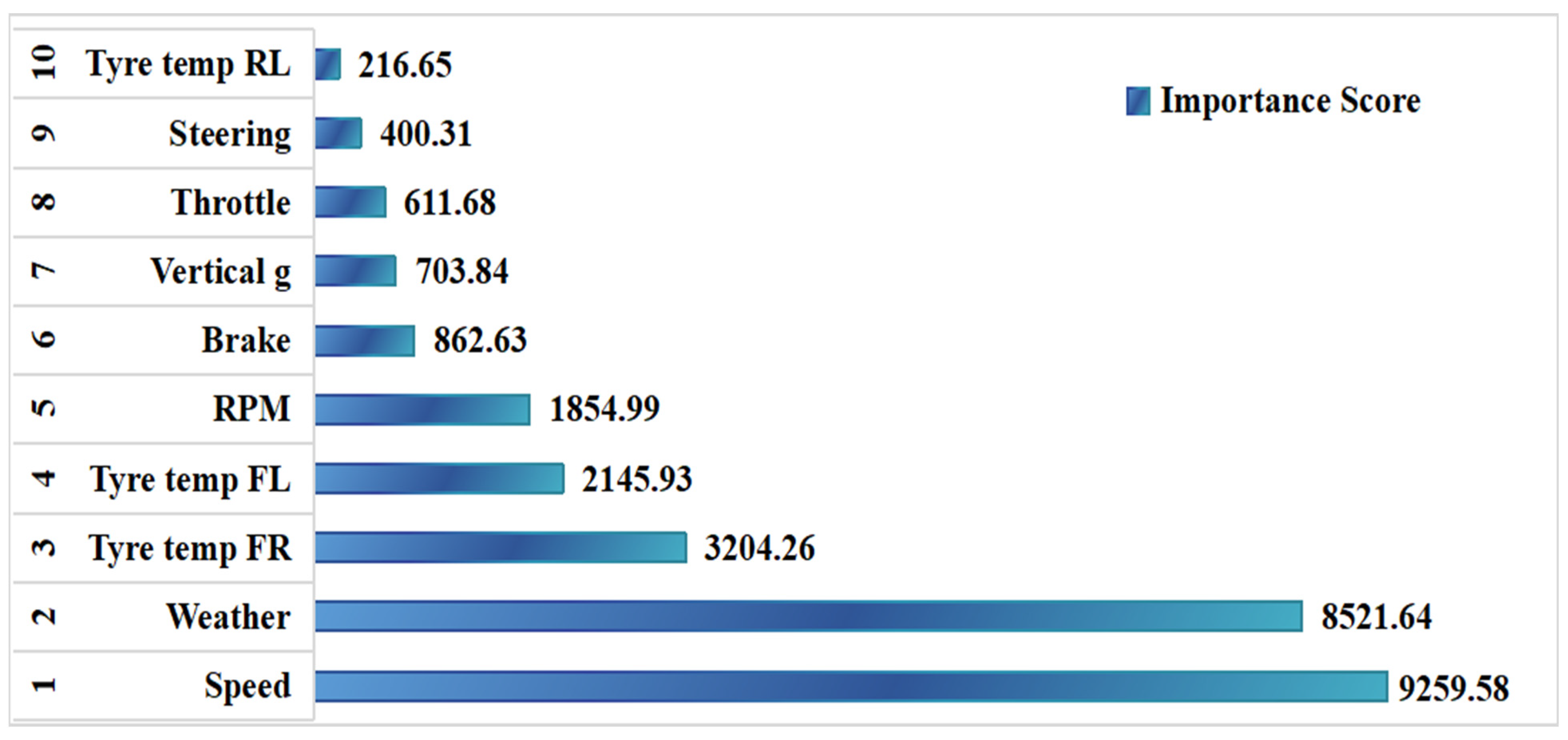

4.1. Results of Feature Selection

4.2. Data Balancing Results

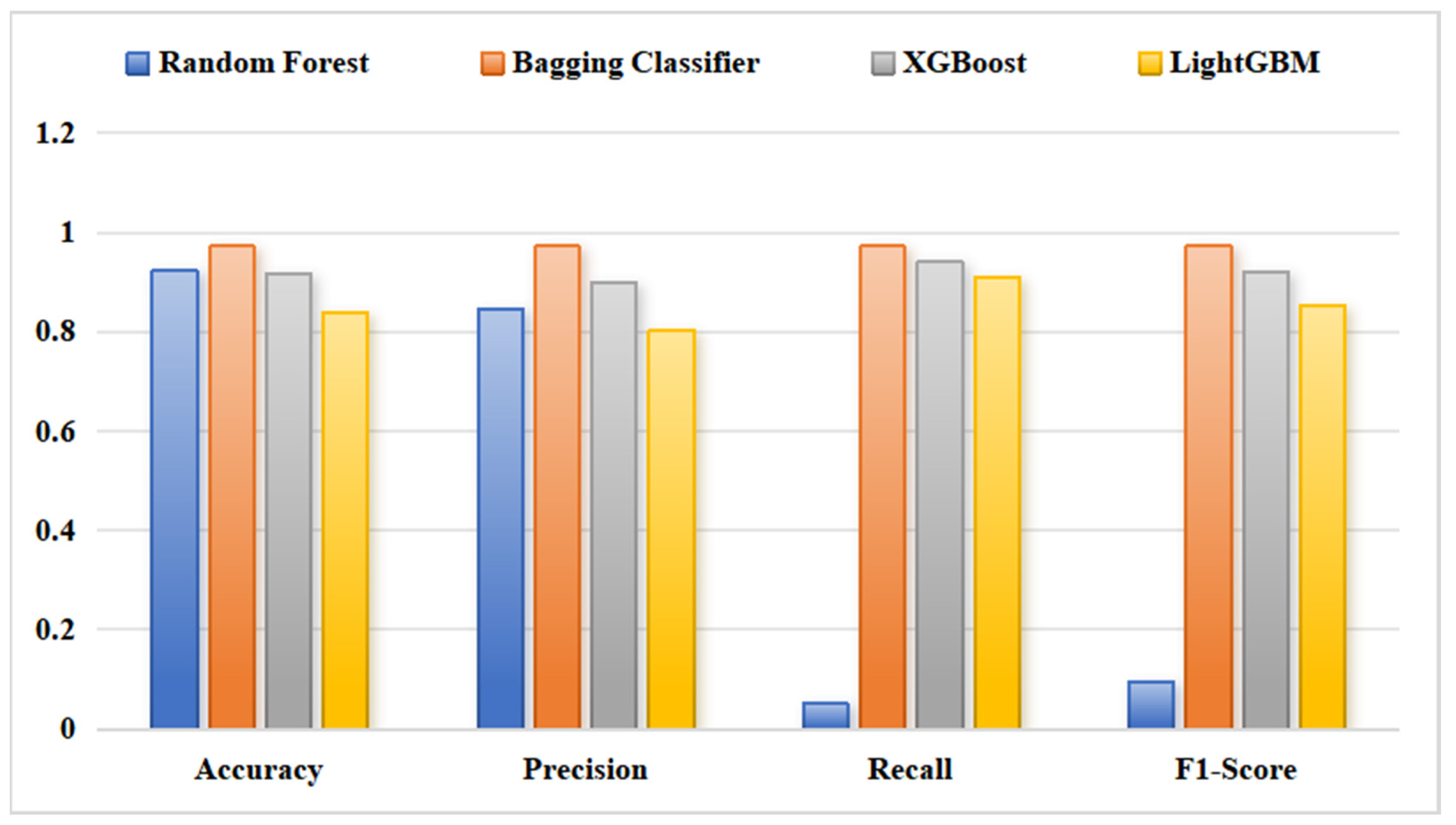

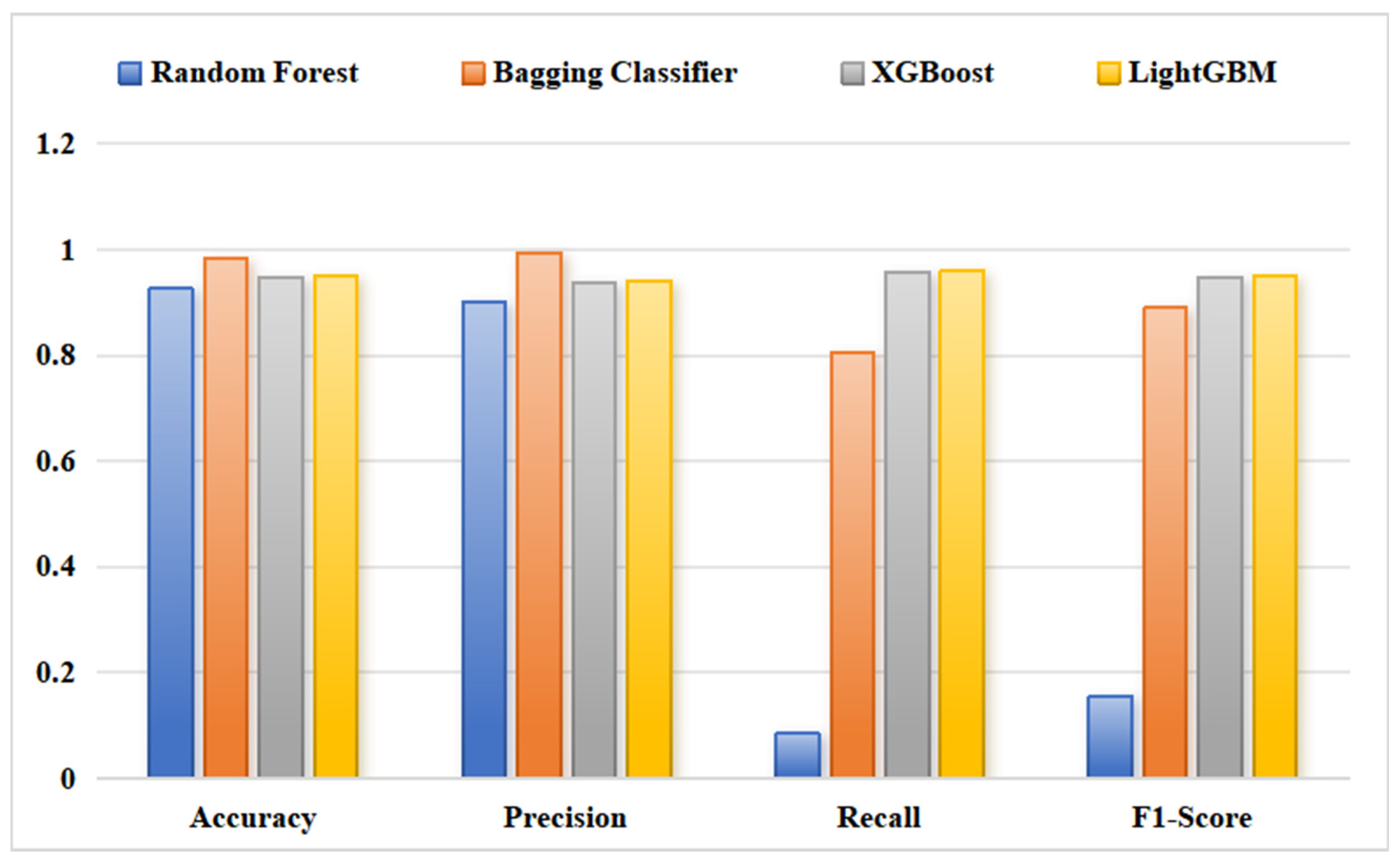

4.3. Performance of Ensemble Machine Learning for Traffic Crash Prediction

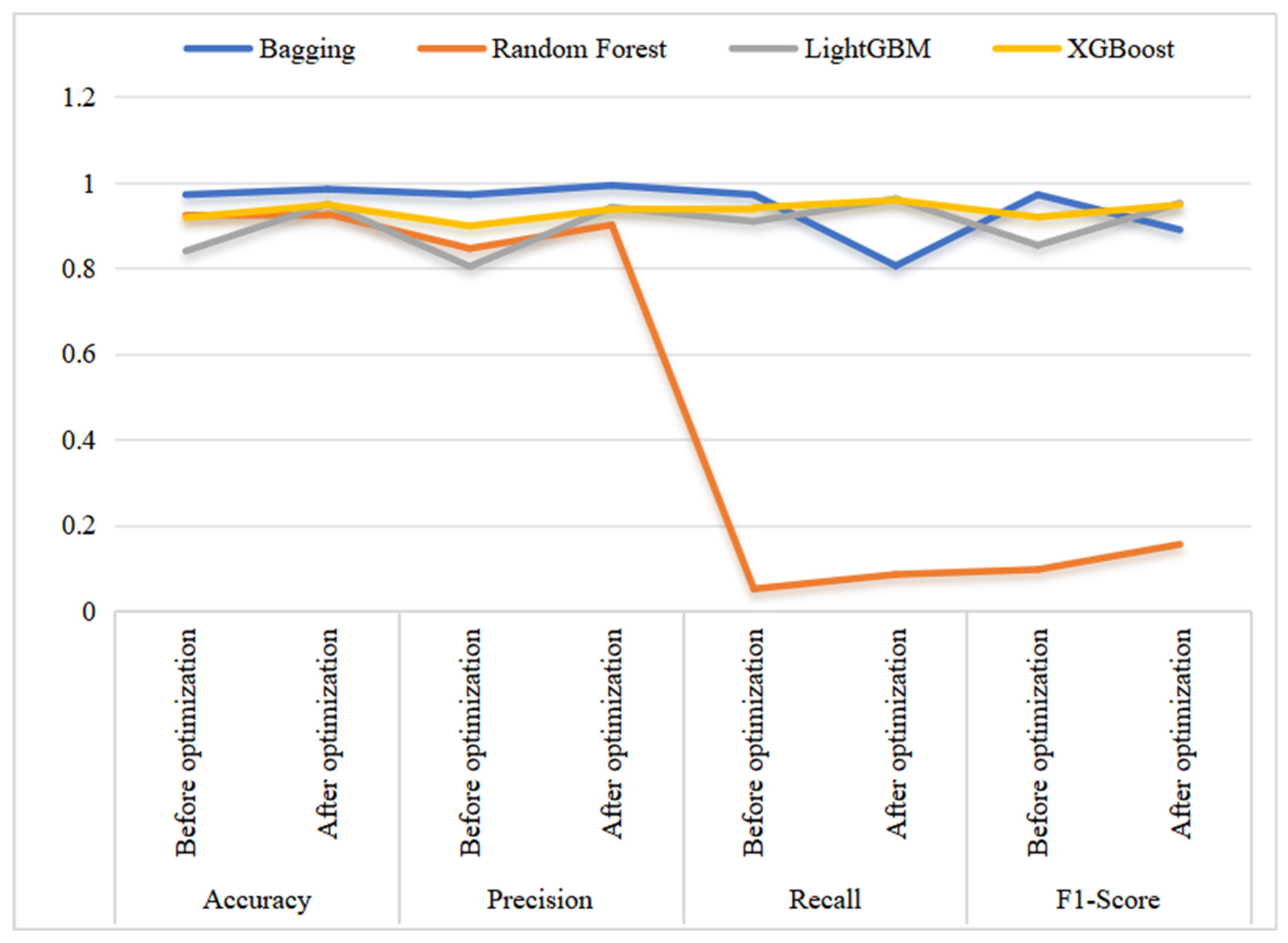

4.4. Optimization and Hyperparameter Tuning Process Results

5. Discussion

5.1. The Interpretation of Features and Derived Insights on Road Safety

5.2. The Supplementary Evaluation Analyses

5.3. Limitations, Model Transferability, and Future Validation

6. Practical Deployment of Trained Models

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/road-safety#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- The National Road Safety Agency of Morocco. Available online: https://www.narsa.ma/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- El Ferouali, S.; Elamrani Abou Elassad, Z.; Abdali, A. Understanding the Factors Contributing to Traffic Accidents: Survey and Taxonomy. In Artificial Intelligence, Data Science and Applications: ICAISE 2023; Farhaoui, Y., Hussain, A., Saba, T., Taherdoost, H., Verma, A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameksa, M.; Mousannif, H.; Al Moatassime, H.; Elamrani Abou Elassad, Z. Toward Flexible Data Collection of Driving Behaviour. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, XLIV-4/W3-2020, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Zheng, O.; Wu, Y. Applying machine learning and google street view to explore effects of drivers’ visual environment on traffic safety. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 135, 103541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Abdel-Aty, M. Real-time crash potential prediction on freeways using connected vehicle data. Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 2022, 36, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, H.; Fu, T.; Behan, M.; Jie, L.; He, Y.; Shangguan, Q. Crash prediction for freeway work zones in real time: A comparison between Convolutional Neural Network and Binary Logistic Regression model. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilatos, A.; Chen, C.; Antoniou, C. Comparing Machine Learning and Deep Learning Methods for Real-Time Crash Prediction. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goubraim, N.; Elassad, Z.E.A.; El-Amarty, N.; Mousannif, H. Advanced Tree-Based Ensemble Learning System for Prediction Accident Severity with Imbalanced Data Handling. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Advances in Communication Technology and Computer Engineering (ICACTCE’24); Iwendi, C., Boulouard, Z., Kryvinska, N., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, H.; Chen, X. PCA-based missing information imputation for real-time crash likelihood prediction under imbalanced data. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2019, 15, 872–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamrani Abou Elassad, Z.; Ameksa, M.; Elamrani Abou Elassad, D.; Mousannif, H. Machine Learning Prediction of Weather-Induced Road Crash Events for Experienced and Novice Drivers: Insights from a Driving Simulator Study. In Business Intelligence; El Ayachi, R., Fakir, M., Baslam, M., Eds.; CBI 2023; Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobermin, M.; Ferreira, S. A novel approach to set driving simulator experiments based on traffic crash data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 150, 105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, R.; Zhuping, Z. Traffic safety forecasting method by particle swarm optimization and support vector machine. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 10420–10424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahdi, A.; Al Mamlook, R.E.; Bandara, N.; Almuflih, A.S.; Nasayreh, A.; Gharaibeh, H.; Alasim, F.; Aljohani, A.; Jamal, A. Boosting Ensemble Learning for Freeway Crash Classification under Varying Traffic Conditions: A Hyperparameter Optimization Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, W. ReMAHA–CatBoost: Addressing Imbalanced Data in Traffic Accident Prediction Tasks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameksa, M.; Mousannif, H.; Al Moatassime, H.; Elamrani Abou Elassad, Z. Application of machine learning techniques for driving errors analysis: Systematic literature review. Int. J. Crashworthiness 2024, 29, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruily, M.; El-Ghany, S.A.; Mostafa, A.M.; Ezz, M.; El-Aziz, A.A.A. A-Tuning Ensemble Machine Learning Technique for Cerebral Stroke Prediction. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezashoar, S.; Kashi, E.; Saeidi, S. A hybrid algorithm based on machine learning (LightGBM-Optuna) for road accident severity classification (case study: United States from 2016 to 2020). Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2024, 9, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuhammadi, S.; Alnajim, A.; Ayub, M. QUIC Network Traffic Classification Using Ensemble Machine Learning Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Aghaabbasi, M.; Ali, M.; Jan, A.; Bouallegue, B.; Javed, M.F.; Salem, N.M. Comparative Analysis of the Optimized KNN, SVM, and Ensemble DT Models Using Bayesian Optimization for Predicting Pedestrian Fatalities: An Advance towards Realizing the Sustainable Safety of Pedestrians. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, E.Y.; Deng, Z.; Magsi, A.H.; Ali, Q.; Kumar, K.; Zubedi, A. Optimizing Skin Cancer Survival Prediction with Ensemble Techniques. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyoo, J.O.; Wekesa, J.S.; Ogada, K.O. Predicting Road Traffic Collisions Using a Two-Layer Ensemble Machine Learning Algorithm. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.R.; Wang, H.; Gupta, C. Predictive Analysis for Optimizing Port Operations. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xing, L.; Yuan, C.; Liu, F.; Wu, D.; Yang, H. Crash injury severity prediction considering data imbalance: A Wasserstein generative adversarial network with gradient penalty approach. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2023, 192, 107271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudnitski, A. Evaluating Road Crash Severity Prediction with Balanced Ensemble Models. Findings 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A.M.; Aldughayfiq, B.; Tarek, M.; Alaerjan, A.S.; Allahem, H.; Elbashir, M.K.; Ezz, M.; Hamouda, E. AI-based prediction of traffic crash severity for improving road safety and transportation efficiency. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujalli, R.O.; López, G.; Garach, L. Bayes classifiers for imbalanced traffic accidents datasets. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 88, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risto, M.; Martens, M.H. Driver headway choice: A comparison between driving simulator and real-road driving. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2014, 25 Pt A, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamrani Abou Elassad, Z.; Mousannif, H. Understanding driving behavior: Measurement, modeling and analysis. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamrani Abou Elassad, Z.; Mousannif, H.; Al Moatassime, H. A proactive decision support system for predicting traffic crash events: A critical analysis of imbalanced class distribution. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 205, 106314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Khalil, T.; Nasreen, S. A survey of feature selection and feature extraction techniques in machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2014 Science and Information Conference, London, UK, 27–29 August 2014; pp. 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, E.; Lindsay, J.; Lee, C.; Măndoiu, I.I.; Nelson, C.E. Feature selection and classifier performance on diverse bio- logical datasets. BMC Bioinform. 2014, 15, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. arXiv 2002, arXiv:1106.1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Yuan, J.; Lee, J.; Wu, Y. Real-time crash prediction on expressways using deep generative models. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 117, 102697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Bagging Predictors. Mach. Learn. 1996, 24, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, C.; Giraldo, I.; Gomez-Gonzalez, J.E.; Uribe, J.M. An explained extreme gradient boosting approach for identifying the time-varying determinants of sovereign risk. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 57, 104273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Xu, H.; Liu, X. Analysis and visualization of accidents severity based on LightGBM-TPE. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 157, 111987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bengio, Y. Random Search for Hyper-Parameter Optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 281–305. [Google Scholar]

- Elamrani Abou Elassad, D.; Elamrani Abou Elassad, Z.; Ed-Dahbi, A.M.; El Meslouhi, O.; Kardouchi, M.; Akhloufi, M.; Jahan, N. A human-in-the-loop ensemble fusion framework for road crash prediction: Coping with imbalanced heterogeneous data from the driver-vehicle-environment system. Transp. Lett. 2024, 17, 827–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Sun, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Lu, Y.; Huo, L. Comparative study of neonatal brain injury fetuses using machine learning methods for perinatal data. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 240, 107701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfati, L.V.; Mendes Junior, J.J.A.; Siqueira, H.V.; Stevan, S.L., Jr. Correlation Analysis of In-Vehicle Sensors Data and Driver Signals in Identifying Driving and Driver Behaviors. Sensors 2023, 23, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Characteristic |

|---|---|

| MacBook | 2015 Pro |

| processor | i7/2.8 GHz |

| Random access memory | 16 GB |

| hard drive | SSD |

| LCD panel | 27-inch/1920 × 1080 pixels |

| Logitech R G27 Racing Wheel set | steering wheel accelerator pedal, brake pedal automated gear selection gear shifter was not required |

| Feature | Description | Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Realistic Vehicle Physics | Simulates tire grip, suspension, and car dynamics with high accuracy | Enables realistic driver behavior analysis and crash scenario testing |

| Dynamic Weather System | Supports rain, fog, snow, and changing weather during a drive | Helps assess driver performance under varying and challenging weather conditions |

| Day/Night Cycle | Full 24-h cycle with realistic lighting and shadows | Useful for visibility studies and night-driving experiments |

| Custom Scenario Setup | Configurable conditions: road type, traffic, vehicle, time, and weather | Facilitates controlled experiments with repeatable conditions |

| Hardware Support | Compatible with racing wheels, pedals, and cockpits (e.g., Logitech G27) | Enhances realism and immersion for participants |

| High-Quality Graphics | Realistic visual representation of roads, vehicles, and environments | Increases participant engagement and ecological validity |

| LiveTrack 3.0 | Road surface dynamically changes with weather and driving activity | Improves realism and enables more nuanced testing of driving response |

| Camera Views | Multiple camera options (cockpit, chase, dash, etc.) | Allows flexible recording and observation perspectives |

| AI Traffic Simulation | Includes AI vehicles with configurable behavior | Useful for testing driver responses to other road users and complex traffic situations |

| Telemetry Support | Compatible with third-party plugins for data capture (e.g., speed, G-force) | Enables detailed data logging and analysis for research purposes |

| VR and Multi-Screen Ready | Supports virtual reality and triple-screen setups | Provides immersive simulation for a better participant experience |

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | 81 volunteers (43 male, 38 female) aged 22–41 |

| Experience | Experienced drivers with normal vision |

| Experiment | Two driving simulation sessions:

|

| Weather Conditions | Clear, fog, rain, snow |

| Data Collection | 20 Hz sampling rate, including:

|

| Crash Distribution | Approximately 26% of crashes occurred under clear conditions, 24% under fog, 29% under rain, and 21% under snow (total crash events: 5951). |

| Data Analysis | Data cleaning and analysis to identify factors influencing crash events, considering variables such as weather conditions, driver behavior, and traffic scenarios. |

| Goal | Understand factors influencing driving behavior and crashes. |

| Key Point | Virtual environment designed to mimic real-world driving conditions with randomly generated traffic scenarios. |

| Feature | Description | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | Magnitude of a vehicle’s velocity | vehicle kinematics |

| Lateral acceleration | Sideways movement of a vehicle | |

| Longitudinal acceleration | Vehicle’s acceleration or deceleration along its direction of travel | |

| Vertical acceleration | Rate at which a vehicle moves vertically | |

| Yaw angle | Angle between a vehicle’s longitudinal axis and its actual line of travel | |

| Drift angle | Angle between a vehicle’s orientation and its velocity vector | |

| Spin angle | Angle at which a vehicle rotates or turns about its vertical axis | |

| Revolutions per minute (RPM) | Number of rotations completed by a vehicle’s engine crankshaft in one minute | |

| Tyre temp FL | Tire temperature measurements front-left (FL) front-right (FR) rear-left (RL) rear-right (RR) provide insights into the wear and performance of each tire. | |

| Tyre temp FR | ||

| Tyre temp RL | ||

| Tyre temp RR | ||

| Throttle | Accelerator pedal position | Driver behavior |

| Brake | Driver’s intention to decelerate or halt the vehicle | |

| Steering | Driver’s intended direction | |

| Weather Season | Prevailing atmospheric conditions during specific time periods or observations | Weather factors |

| Model | Parameter Grid (Searched Values) | Combinations | CV Fits (×5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bagging Classifier | n_estimators: [10, 50, 100]; max_samples: [0.5, 0.8, 1.0]; max_features: [0.5, 0.8, 1.0] | 27 | 135 |

| Random Forest | n_estimators: [100, 200]; max_depth: [5, 10, None]; max_features: [4, “sqrt”] | 12 | 60 |

| XGBoost | learning_rate: [0.01, 0.1, 0.2]; n_estimators: [100, 200]; max_depth: [3, 6, 7]; subsample: [0.8, 1.0] | 36 | 180 |

| LightGBM | learning_rate: [0.01, 0.1]; n_estimators: [100, 200]; num_leaves: [31, 64]; max_depth: [−1, 7]; subsample: [0.8, 1.0] | 16 | 80 |

| Actual/Predicted | Crash | No-Crash |

|---|---|---|

| Crash | True Positive (TP) | False Negative (FN) |

| No-Crash | False Positive (FP) | True Negative (TN) |

| Model | Best Hyperparameters |

|---|---|

| Random Forest | max_depth: 5, max_features: 4, n_estimators: 200 |

| Bagging Classifier | max_features: 0.8, max_samples: 1.0, n_estimators: 100 |

| XGBoost | learning_rate: 0.2, max_depth: 7, n_estimators: 200, subsample: 0.8 |

| LightGBM | learning_rate: 0.1, max_depth: −1, n_estimators: 100, num_leaves: 31 |

| Model | TP | FP | FN | TN | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 171 | 19 | 1043 | 13,948 | 15,181 |

| Bagging Classifier | 984 | 10 | 230 | 13,957 | 15,181 |

| XGBoost | 622 | 39 | 568 | 13,952 | 15,181 |

| LightGBM | 460 | 29 | 730 | 13,962 | 15,181 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goubraim, N.; Elassad, Z.E.A.; Mousannif, H.; Ameksa, M. Boosting Traffic Crash Prediction Performance with Ensemble Techniques and Hyperparameter Tuning. Safety 2025, 11, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040121

Goubraim N, Elassad ZEA, Mousannif H, Ameksa M. Boosting Traffic Crash Prediction Performance with Ensemble Techniques and Hyperparameter Tuning. Safety. 2025; 11(4):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040121

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoubraim, Naima, Zouhair Elamrani Abou Elassad, Hajar Mousannif, and Mohamed Ameksa. 2025. "Boosting Traffic Crash Prediction Performance with Ensemble Techniques and Hyperparameter Tuning" Safety 11, no. 4: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040121

APA StyleGoubraim, N., Elassad, Z. E. A., Mousannif, H., & Ameksa, M. (2025). Boosting Traffic Crash Prediction Performance with Ensemble Techniques and Hyperparameter Tuning. Safety, 11(4), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040121