Exploring Flood-Related Unintentional Fatal Drowning of Children and Adolescents Aged 0–19 Years in Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analyses and Ethics

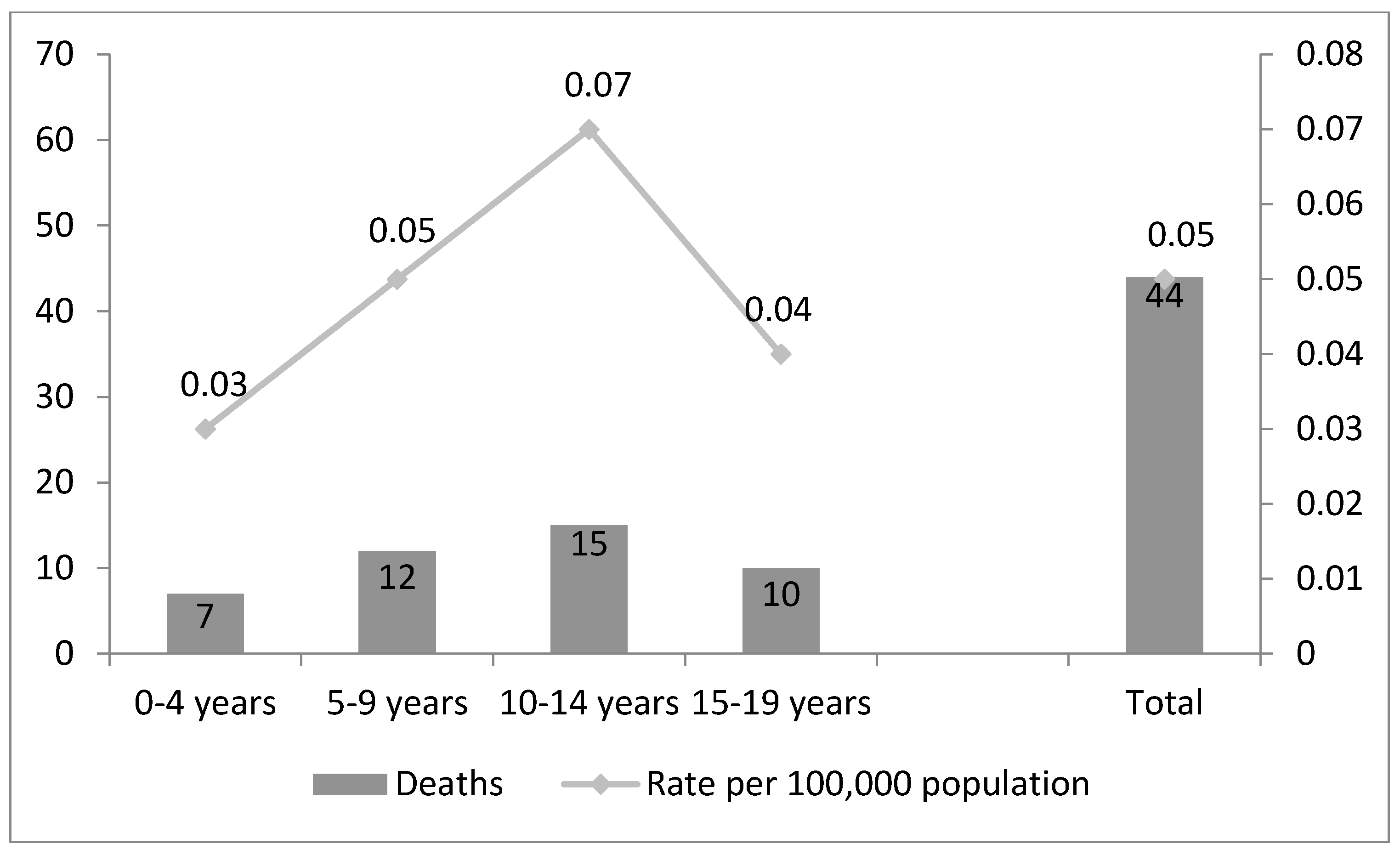

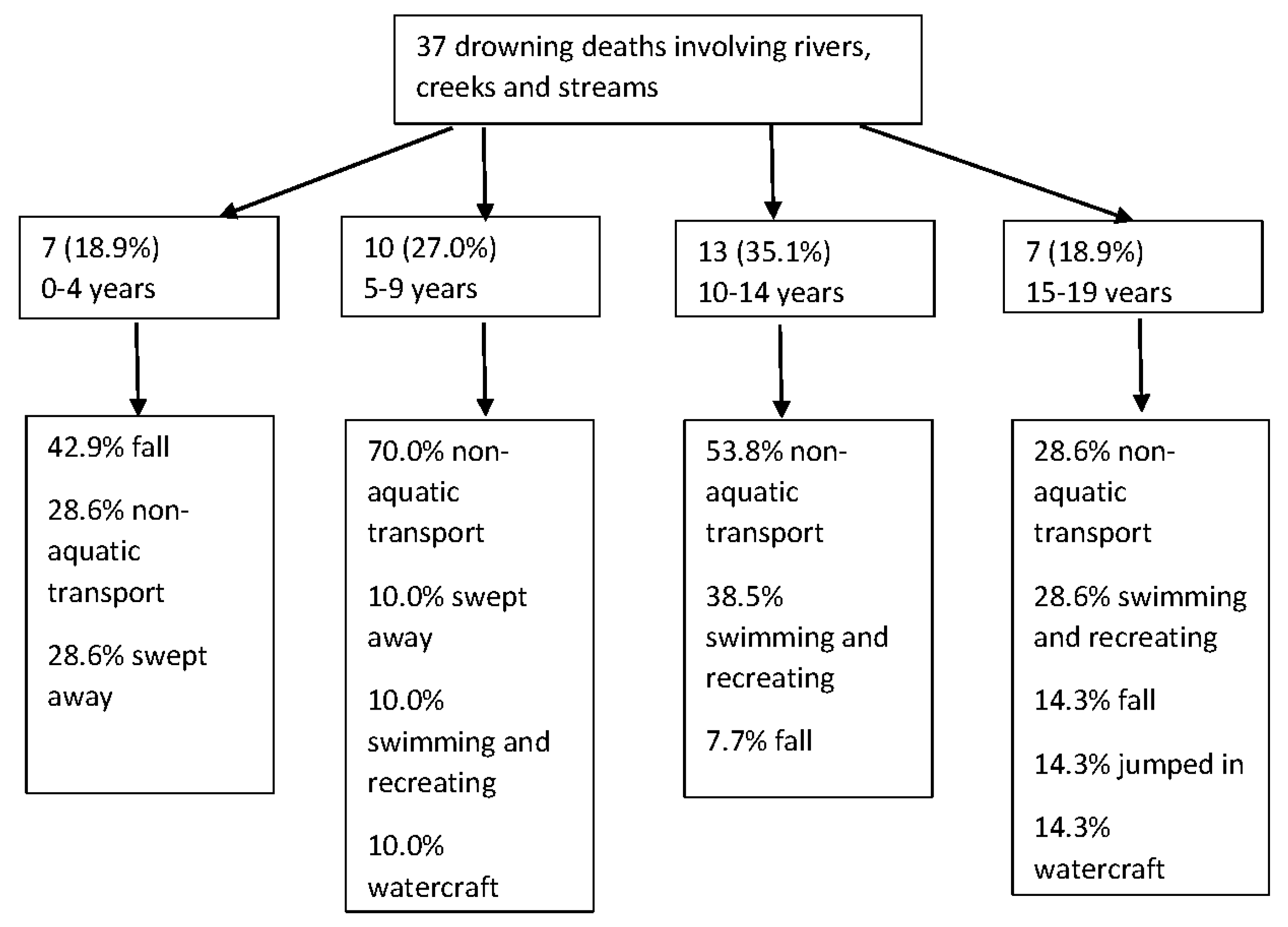

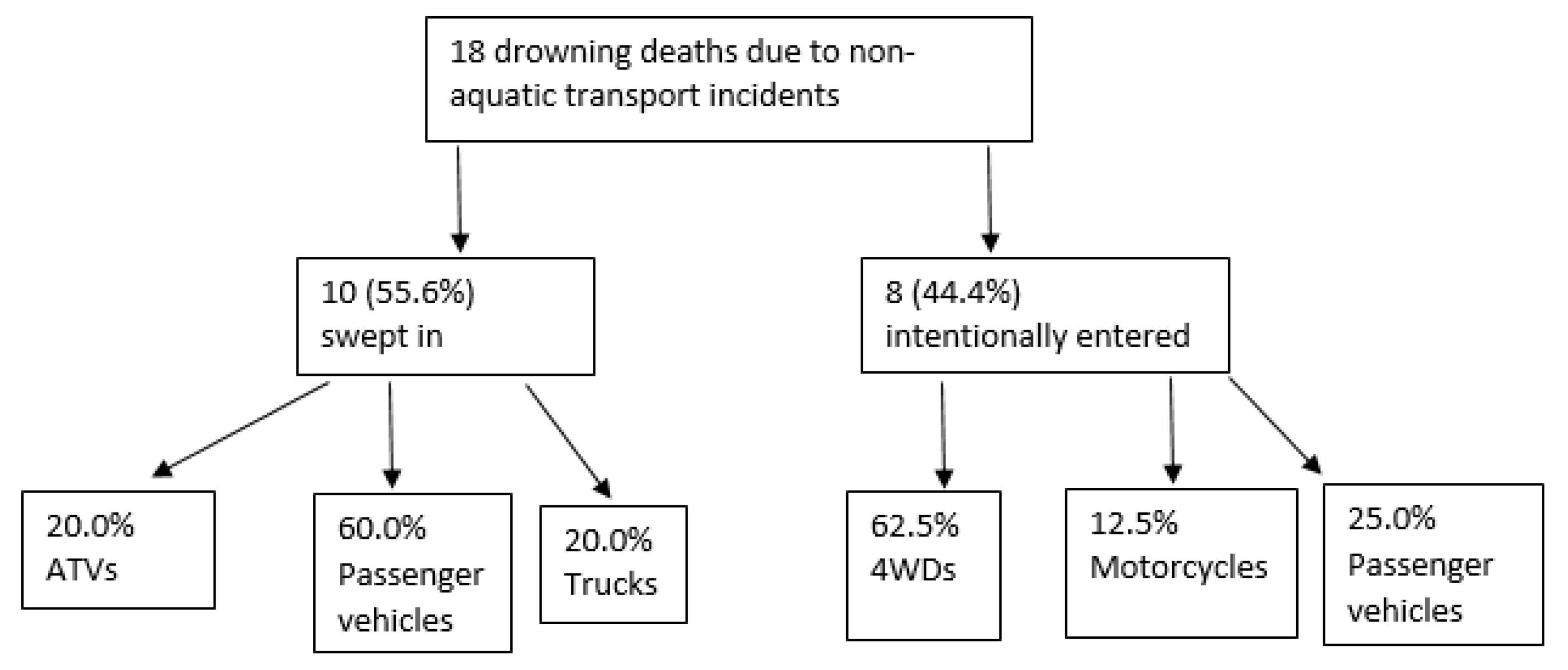

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Flood-Related Child Drowning Risk Profile by Age

4.2. Risks of Driving into Floodwaters

4.3. Risk of Swimming in Floodwaters

4.4. Social Determinants Impacting Flood Drowning Risk

4.5. Implications for Prevention and Opportunities for Further Research

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashley, S.T.; Ashley, W.S. Flood Fatalities in the United States. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2008, 47, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Drowning: Preventing a Leading Killer; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, R.C.; Peden, A.E. Improving Pool Fencing Legislation in Queensland, Australia: Attitudes and Impact on Child Drowning Fatalities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, L.; Gore, E.J.; Wentz, K.; Allen, J.; Novack, A.H. Ten-year study of pediatric drownings and near-drownings in King County, Washington: Lessons in Injury Prevention. Pediatrics 1989, 83, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peden, A.E.; Franklin, R.C.; Pearn, J.H. Unintentional fatal child drowning in the bath: A 12-year Australian review (2002–2014). J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 54, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; Mashreky, S.R.; Chowdhury, S.M.; Giashuddin, M.S.; Uhaa, I.J.; Shafinaz, S.; Rahman, F. Analysis of the childhood fatal drowning situation in Bangladesh: Exploring prevention measures for low income countries. Inj. Prev. 2009, 15, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Preventing Drowning: An Implementation Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peden, A.E.; Franklin, R.C.; Mahony, A.; Barnsley, P.; Scarr, J. Using a retrospective cross-sectional study to analyse unintentional fatal drowning in Australia: ICD-10 coding-based methodologies verses actual deaths. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e019407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR). Guidelines for Reducing Flood Losses; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR): Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED); United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR). 2018 Review of Disaster Events. 2019. Available online: https://www.cred.be/publications (accessed on 3 March 2019).

- Di Mauro, M.; de Bruijn, K.M.; Meloni, M. Quantitative methods for estimating flood fatalities towards the introduction of loss-of-life estimation in the assessment of flood risk. Nat. Hazards 2012, 63, 1083–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doocy, S.; Daniels, A.; Murray, S.; Kirsch, T.D. The Human Impact of Floods: A Historical Review of Events 1980–2009 and Systematic Literature Review. PLoS Curr. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peden, A.E.; Franklin, R.C.; Leggat, P.A. Causal Pathways of Flood Related River Drowning Deaths in Australia. PLoS Curr. Dis. 2017, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, L. Flood Fatalities in Australia, 1788–1996. Aust. Geogr. 1999, 30, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, K.; Coates, L.; van den Honert, R.; Gissing, A.; Bird, D.; de Oliveira, F.D.; Radford, D. Exploring the circumstances surrounding flood fatalities in Australia—1900–2015 and the implications for policy and practice. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 76, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Peden, A.E.; Pearson, M.; Hagger, M.S. Stop there’s water on the road! Identifying key beliefs guiding people’s willingness to drive through flooded waterways. Saf. Sci. 2016, 86, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Peden, A.E.; Keech, J.J.; Hagger, M.S. Changing people’s attitudes and beliefs toward driving through floodwaters: Evaluation of a video infographic. Transport. Res. Part F 2018, 53, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Keech, J.J.; Peden, A.E.; Hagger, M.S. Protocol for developing a mental imagery intervention: A randomized controlled trial testing a novel implementation imagery e-health intervention to change driver behavior during floods. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, K.; Peden, A.E.; Keech, J.J.; Hagger, M.S. Driving through floodwater; Exploring driver decisions through the lived experience. Int. J. Dis. Risk Reduct. 2019, 34, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Price, S.; Keech, J.J.; Peden, A.E.; Hagger, M.S. Drivers’ experiences during floods: Investigating the psychological influences underpinning decisions to avoid driving through floodwater. Int. J. Dis. Risk Reduct. 2018, 28, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keech, J.J.; Smith, S.R.; Peden, A.E.; Hagger, M.S.; Hamilton, K. The lived experience of rescuing people who have driven into floodwater: Understanding challenges and identifying areas for providing support. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2019, 30, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peden, A.E.; Franklin, R.C.; Leggat, P.A. The Flood-Related Behavior of River Users in Australia. PLoS Curr. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, R.C.; King, J.C.; Aitken, P.J.; Leggat, P.A. “Washed away”—Assessing community perceptions of flooding and prevention strategies: A North Queensland example. Nat. Hazards 2014, 73, 1977–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.J.; Priest, S.J.; Tapsell, S.M. Understanding and enhancing the public’s behavioural response to flood warning information. Meterol. Appl. 2009, 16, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, S.; Qasim, M.; Shrestha, R.P.; Khan, A.N.; Tun, K.; Ashraf, M. Community resilience to flood hazards in Khyber Pukhthunkhwa province of Pakistan. Int. J. Dis. Risk Reduct. 2016, 18, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.K.; Rahman, M.; van Ginneken, J. Epidemiology of child deaths due to drowning in Matlab, Bangladesh. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1999, 28, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, E.K.; West, K.P., Jr.; Katz, J.; LeClerq, S.C.; Khatry, S.K.; Shrestha, S.R. Risk of flood-related mortality in Nepal. Disasters 2007, 31, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttmann, A.; Razzaq, A.; Lindsay, P.; Zagorski, B.; Anderson, G.M. Development of Measures of the Quality of Emergency Department Care for Children Using a Structured Panel Process. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victorian Department of Justice and Community Safety. National Coronial Information System. 2018. Available online: www.ncis.org.au (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Peden, A.E.; Franklin, R.C.; Leggat, P.A. Preventing river drowning deaths: Lessons from coronial recommendations. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2018, 29, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peden, A.E.; Franklin, R.C.; Leggat, P.A. Alcohol and its contributory role in fatal drowning in Australian rivers, 2002–2012. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 98, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonkman, S.N.; Kelman, I. An Analysis of the Causes and Circumstances of Flood Disaster Deaths. Disasters 2005, 29, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Centre for Classification in Health Australia. ICD-10-AM Tabular List of Diseases; National Centre for Classification in Health Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Life Saving Society—Australia. Royal Life Saving Society—Australia Drowning Database Definitions and Coding Manual; Peden, A.E., Ed.; Royal Life Saving Society—Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2033.0.55.001—Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA); Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Geography Volume 1—Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC); Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2006.

- McBain-Rigg, K.E.; Franklin, R.C.; McDonald, G.C.; Knight, S.M. Why Quad Bike Safety is a Wicked Problem: An Exploratory Study of Attitudes, Perceptions and Occupational Use of Quad Bikes in Northern Queensland, Australia. J. Agric. Saf. Health 2014, 20, 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3101.0. Australian Demographic Statistics, March 2018. Table 59. Estimated Resident Population by Single Year of Age; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2011 Census QuickStats; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016 Census QuickStats; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2017.

- Martin, M.L. Child Participation in Disaster Risk Reduction: The case for flood-affected children in Bangladesh. Third World Q. 2010, 31, 1357–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugeja, L.; Franklin, R.C. Drowning deaths of zero-to-five-year-old children in Victorian dams, 1989–2001. Aust. J. Rural Health 2005, 13, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D.; Harris, E. Theory in a Nutshell: A Practitioner’s Guide to Commonly Used Theories and Models in Health Promotion; National Centre for Health Promotion, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine: Sydney, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Szpilman, D.; Webber, J.; Quan, L.; Bierens, J.; Morizot-Leite, L.; Langendorfer, S.J.; Løfgren, B. Creating a drowning chain of survival. Resuscitation 2014, 85, 1149–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, G.K.; Giesbrecht, G.G. Vehicle submersion: A review of the problem, associated risks, and survival information. Aviat Space Environ. Med. 2013, 84, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, L. Risk Taking in Adolescence: New Perspectives from Brain and Behavioural Science. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters; United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR): Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme, L. Explaining socio-economic differences in injury risks. Injury Control. Saf. Promot. 2001, 8, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reading, R. Serious injuries in children: Variation by area deprivation and settlement type. Child Care Health Dev. 2008, 34, 485–489. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, F. Population Decline in Non-Metropolitan Australia: Impacts and Policy Implications. Urban Policy Res. 1994, 12, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridirici, R. Floods of People: New Residential Development into Flood-Prone Areas in San Joaquin County, California. Nat. Hazards 2008, 9, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilling, J.D.; Sirmans, C.F.; Benjamin, J.D. Flood insurance, wealth distribution, and urban property values. J. Urban. Economics 1989, 26, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnsley, P.D.; Peden, A.E.; Scarr, J. Calculating the economic burden of fatal drowning in Australia. J. Saf. Res. 2018, 67, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry. Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry-Final Report; Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry: Brisbane, Australia, 2012.

- Peden, A.E.; Franklin, R.C.; Clemens, T. Exploring the burden of fatal drowning and data characteristics in three high income countries: Australia, Canada and New Zealand. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Male | Female | X2 (p Value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Total | 44 | 100.0 | 28 | 63.6 | 16 | 36.4 | 2.680 (p = 0.102) |

| Age group | |||||||

| 0–4 years | 7 | 15.9 | NP | 42.9 | 4 | 57.1 | 0.236 (p = 0.205) * |

| 5–9 years | 12 | 27.3 | 7 | 58.3 | 5 | 41.7 | 0.732 (p = 0.456) * |

| 10–14 years | 15 | 34.1 | 10 | 66.7 | 5 | 33.3 | 1.000 (p= 0.516) * |

| 15–17 years | 10 | 22.7 | 8 | 80.0 | NP | 20.0 | 0.283 (p = 0.200) * |

| Location of drowning incident | |||||||

| River/Creek/Stream | 37 | 84.1 | 21 | 56.8 | 16 | 43.2 | 0.037 (p = 0.031) * |

| Drain | 7 | 15.9 | 7 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Type of flooding | |||||||

| Flash flood | 14 | 31.8 | 6 | 42.9 | 8 | 57.1 | 7.418 (p = 0.013) * |

| Slow onset | 13 | 29.5 | 12 | 92.3 | NP | 7.7 | |

| Unknown | 17 | 38.6 | 10 | 58.8 | 7 | 41.2 | - |

| Activity undertaken immediately prior to drowning | |||||||

| Fall | 7 | 15.9 | 5 | 71.4 | NP | 28.6 | 1.000 (p = 0.496) * |

| Jumped In | NP | 4.5 | NP | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.526 (p = 0.400) * |

| Non-aquatic Transport | 18 | 40.9 | 10 | 55.6 | 8 | 44.4 | 0.525 (p = 0.466) * |

| Swept Away | 3 | 6.8 | NP | 33.3 | NP | 66.7 | 0.543 (p = 0.296) * |

| Swimming and Recreating | 11 | 25.0 | 7 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1.000 (p = 0.635) * |

| Watercraft | NP | 6.8 | NP | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.290 (p = 0.247) * |

| Season of drowning incident | |||||||

| Summer | 24 | 54.5 | 17 | 70.8 | 7 | 29.2 | 0.352 (p = 0.220) * |

| Autumn | 7 | 15.9 | 4 | 57.1 | NP | 42.9 | 0.692 (p= 0.504) * |

| Winter | 5 | 11.4 | NP | 60.0 | NP | 40.0 | 1.000 (p = 0.608) * |

| Spring | 8 | 18.2 | 4 | 50.0 | 4 | 50.0 | 0.434 (p = 0.310) * |

| Time of day of drowning incident (n = 42) | |||||||

| Early Morning | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | UTBC |

| Morning | 8 | 19.0 | 6 | 75.0 | NP | 25.0 | 0.697 (p = 0.457) * |

| Afternoon | 26 | 61.9 | 18 | 69.2 | 8 | 30.8 | 0.742 (p = 0.452) * |

| Evening | 8 | 19.0 | 4 | 50.0 | 4 | 50.0 | 0.406 (p = 0.240) * |

| Remoteness classification of incident location | |||||||

| Major Cities | 9 | 20.5 | 7 | 77.8 | NP | 22.2 | 0.450 (p = 0.280) * |

| Inner Regional | 13 | 29.5 | 8 | 61.5 | 5 | 38.5 | 1.000 (p = 0.557) * |

| Outer Regional | 11 | 25.0 | 8 | 72.7 | NP | 27.3 | 0.719 (p = 0.365) * |

| Remote | 4 | 9.1 | NP | 75.0 | NP | 25.0 | 1.000 (p =0.537) * |

| Very Remote | 7 | 15.9 | NP | 28.6 | 5 | 71.4 | 0.080 (p = 0.049) * |

| IRSAD classification of child’s residential location | |||||||

| Low | 19 | 43.2 | 11 | 57.9 | 8 | 42.1 | 0.540 (p = 0.353) * |

| Mid | 23 | 52.3 | 15 | 65.2 | 8 | 34.8 | 1.000 (p = 0.533) * |

| High | NP | 4.5 | NP | 100.0 | NP | NP | 0.526 (p = 0.400) * |

| Total | 0–4 Years | 5–9 Years | 10–14 Years | 15–19 Years | X2 (p Value) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Total | 44 | 100.0 | 7 | 15.9 | 12 | 27.3 | 15 | 34.1 | 10 | 22.7 | 3.333 (p = 0.343) |

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 28 | 63.6 | NP | 10.7 | 7 | 25.0 | 10 | 35.7 | 8 | 28.6 | 2.669 (p = 0.446) |

| Female | 16 | 36.4 | 4 | 25.0 | 5 | 31.3 | 5 | 31.3 | NP | 12.5 | |

| Location of drowning incident | |||||||||||

| River/Creek/Stream | 37 | 84.1 | 7 | 18.9 | 10 | 27.0 | 13 | 35.1 | 7 | 18.9 | 2.888 (p= 0.409) |

| Drain | 7 | 15.9 | 0 | 0.0 | NP | 28.6 | NP | 28.6 | NP | 42.9 | |

| Type of flooding | |||||||||||

| Flash flooding | 14 | 31.8 | 5 | 35.7 | 5 | 35.7 | NP | 21.4 | NP | 7.1 | 8.975 (p = 0.030) |

| Slow onset | 13 | 29.5 | NP | 7.7 | NP | 7.7 | 6 | 46.2 | 5 | 38.5 | |

| Unknown | 17 | 38.6 | NP | 5.9 | 6 | 35.3 | 6 | 35.3 | 4 | 23.5 | - |

| Activity undertaken immediately prior to drowning | |||||||||||

| Fall | 7 | 15.9 | NP | 42.9 | NP | 14.3 | NP | 14.3 | NP | 28.6 | 5.397 (p = 0.145) |

| Jumped In | 2 | 4.5 | 0 | 0.0 | NP | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | NP | 50.0 | 2.130 (p = 0.546) |

| Non-aquatic Transport | 18 | 40.9 | NP | 11.1 | 7 | 38.9 | 7 | 38.9 | NP | 11.1 | 3.962 (p = 0.266) |

| Swept Away | 3 | 6.8 | NP | 66.7 | NP | 33.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7.086 (p=0.069) |

| Swimming and Recreating | 11 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 | NP | 9.1 | 6 | 54.5 | 4 | 36.4 | 7.111 (p = 0.068) |

| Watercraft | NP | 6.8 | 0 | 0.0 | NP | 33.3 | NP | 33.3 | NP | 33.3 | 0.715 (p = 0.870) |

| Season of drowning incident | |||||||||||

| Summer | 24 | 54.5 | NP | 12.5 | 6 | 25.0 | 8 | 33.3 | 7 | 29.2 | 1.458 (p = 0.692) |

| Autumn | 7 | 15.9 | 0 | 0.0 | NP | 28.6 | 4 | 57.1 | NP | 14.3 | 2.888 (p = 0.409) |

| Winter | 5 | 11.4 | NP | 40.0 | NP | 20.0 | NP | 40.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3.507 (p = 0.320) |

| Spring | 8 | 18.2 | NP | 25.0 | NP | 37.5 | NP | 12.5 | NP | 25.0 | 2.242 (p = 0.524) |

| Time of day of drowning incident (n = 42) | |||||||||||

| Early Morning | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | UTBC |

| Morning | 8 | 19.0 | NP | 25.0 | NP | 25.0 | 4 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4.015 (p = 0.260) |

| Afternoon | 26 | 61.9 | 4 | 15.4 | 7 | 26.9 | 8 | 30.8 | 7 | 26.9 | 0.535 (p = 0.911) |

| Evening | 8 | 19.0 | 0 | 0.0 | NP | 37.5 | NP | 25.0 | NP | 37.5 | 2.671 (p = 0.445) |

| Remoteness classification of incident location | |||||||||||

| Major Cities | 9 | 20.5 | NP | 11.1 | NP | 33.3 | NP | 33.3 | NP | 22.2 | 0.319 (p = 0.956) |

| Inner Regional | 13 | 29.5 | 4 | 30.8 | NP | 15.4 | NP | 23.1 | 4 | 30.8 | 4.699 (p = 0.195) |

| Outer Regional | 11 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 45.5 | NP | 27.3 | NP | 27.3 | 4.444 (p = 0.217) |

| Remote | 4 | 9.1 | NP | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | NP | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5.741 (p = 0.125) |

| Very Remote | 7 | 15.9 | 0 | 0.0 | NP | 28.6 | 4 | 57.1 | NP | 14.3 | 2.888 (p = 0.409) |

| IRSAD classification of child’s residential location | |||||||||||

| Low | 19 | 43.2 | 5 | 26.3 | 3 | 15.8 | 6 | 31.6 | 5 | 26.3 | 4.145 (p = 0.246) |

| Mid | 23 | 52.3 | 2 | 8.7 | 8 | 34.8 | 8 | 34.8 | 5 | 21.7 | 2.600 (p = 0.457) |

| High | NP | 4.5 | 0 | 0.0 | NP | 50.0 | NP | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1.362 (p =0.714) |

| Number of Drowning Deaths | Rate/100,000 Population | Relative Risk (RR) (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Cities | 9 | 0.02 | 1 |

| Inner Regional | 13 | 0.11 | 5.38 (2.30–12.58) |

| Outer Regional | 11 | 0.20 | 9.44 (3.91–22.79) |

| Remote | 4 | 0.48 | 22.52 (6.94–73.13) |

| Very Remote | 7 | 1.21 | 56.71 (21.12–152.27) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peden, A.E.; Franklin, R.C. Exploring Flood-Related Unintentional Fatal Drowning of Children and Adolescents Aged 0–19 Years in Australia. Safety 2019, 5, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety5030046

Peden AE, Franklin RC. Exploring Flood-Related Unintentional Fatal Drowning of Children and Adolescents Aged 0–19 Years in Australia. Safety. 2019; 5(3):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety5030046

Chicago/Turabian StylePeden, Amy E., and Richard C. Franklin. 2019. "Exploring Flood-Related Unintentional Fatal Drowning of Children and Adolescents Aged 0–19 Years in Australia" Safety 5, no. 3: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety5030046

APA StylePeden, A. E., & Franklin, R. C. (2019). Exploring Flood-Related Unintentional Fatal Drowning of Children and Adolescents Aged 0–19 Years in Australia. Safety, 5(3), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety5030046