1. Introduction

Worldwide, the forest industry, understood here as industries processing forest-based raw materials such as sawmills, pulp mills, and papermills, is one of the most affected by fatal accidents [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In Sweden for example, out of 18 industries, the number of deadly accidents at work in the agricultural, fishing, and forest industries was the third highest between 2013 and 2022 [

5]. Moreover, the manufacturing of wood, and wood-based products as well as the production of paper and paper-based products account for 765 accidents in Sweden in 2023 [

6,

7], which is 14% of the total amount of accidents in the Swedish manufacturing sector. Thus, the forest industry is one of the most accident-affected industries [

8]. Therefore, there is a tremendous societal and ethical need for an improved understanding of safety in the forest industry.

Most of the literature about safety in the forest industry, be it from medical, engineering, or production management fields, shares a common focus on the effect of measurable and physical aspects on work safety. While these insights are relevant and important, research about more intangible factors is not as developed and scattered among different disciplines, knowledge traditions, and methodological approaches [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Safety culture as part of organizational culture [

13,

14], is such an important intangible safety factor. Safety culture means in the Swedish context “the shared attitudes, values and perceptions that managers and employees have about safety and the working environment” [

15]. Safety culture evolves around normative, pragmatic, and anthropological notions, which entail policies and structures, behavioural norms and practices, and attitudes and values [

16].

However, although safety culture is thoroughly researched in varying contexts, the mechanisms and driving forces of how safety culture is created often remain a theoretical and practical black box. At this point, co-creation is argued to be a valuable and novel lens to understand the everyday manifestations, practices, driving forces and mechanisms of safety culture. Co-creation can be understood as an “interactive process where the involved actors collaborate to create value for each other” [

17] through innovation and interaction, facilitating and experiencing actors, networking entities, and organizing and engaging aspects [

18,

19]. In this sense, co-creation can be considered a valuable way to understand workplace safety development further in areas where physical measure-focused factors do not have a sufficient effect [

8,

20].

For these reasons, and as there is no empirical inquiry about how safety culture is created between different organizational entities in the Swedish forest industry, there is a clear need for shedding light on safety culture co-creation mechanisms and driving forces in connection to workplace safety in the forest industry as example of the processing sector. Based on this need, the aim and purpose of this article is to investigate, capture and theorize safety culture co-creation mechanisms and driving forces between varying organizational entities for establishing, managing, and improving sustainable and holistic workplace safety. The research question can thus be formulated as follows:

RQ1: What co-creation mechanisms and driving forces can be identified in workplace safety culture in the forest industry?

This paper contributes by shedding light on the formerly under-researched topic of safety culture co-creation and advancing theory development in this realm. Second, it creates robust and practically relevant insights into safety culture co-creation mechanisms and driving in the forest industry that can be applied to and discussed in similar contexts in processing and manufacturing industries in need for enhancing their safety work. Third, it connects two notions, safety culture and co-creation, that have been researched in isolation. This novel approach provides an empirically informed safety culture co-creation model that can serve as a basis for scholars and practitioners for understanding, establishing, facilitating, and managing workplace safety across different organizational actors, which helps to improve safety beyond physical measurable safety outcomes.

1.1. Workplace Safety

Workplace safety can be understood as a characteristic of work systems that means the low likelihood of immediate or delayed physical or psychological, intentional or unintentional harm to, for example, persons, property, or the environment while performing tasks related to work [

12]. Organizational safety antecedents are contextual factors containing safety culture, policies, practices, leaders, and colleagues, as well as job characteristics like risks, hazards, and job demands. Also, apart from lagging indicators such as accident rates, leading indicators of workplace safety are patterns and norms of safety-related work behaviour. Individual safety antecedents are individual behaviour-outcome expectations, abilities, attitudes and personality traits, personal cognitive and physical resources, safety knowledge, skills, and motivation [

12]. Thus, one of the most important leading indicators is behaviour, including personal protective equipment usage, engagement in risk-reducing practices at work, communication of accidents and hazards, and leveraging employee rights and responsibilities [

21]. However, workplace safety needs to be approached from a more holistic perspective that understands safety as a synergy between humans, machines, environments, work activities, and organizational structures and processes [

22,

23,

24].

1.2. Safety Culture

When defining safety culture, some authors employ a traditional understanding of culture, for example by grounding safety culture in normative (changeable factors like policies, procedures and structures), pragmatic (behavioural norms and practices), and anthropological (beliefs, assumptions, expectations, attitudes and values) cultural assumptions [

16]. Another perspective is employed by connecting safety culture to social identity, where safety culture entails factors such as training, communication, teamwork and leadership [

25]. Others adopt a management lens that focuses on safety culture as part of organizational culture [

14,

26] or in connection to national culture [

13]. A special approach to safety culture is provided by Haukelid et al. [

14], who add integration (an agreed-upon and consistent organizational understanding of safety culture), differentiation (varying interpretations concerning safety, resulting in sub-safety cultures) and fragmentation (no common understanding of safety culture) dimensions to the safety culture notion. Additionally, this perspective on safety culture emphasizes that there are different levels of culture—the most superficial discursive and linguistic level, the mid-layer tacit knowledge level, and the most profound philosophical and epistemological level—and that cultural analysis and change are more challenging to achieve the deeper the cultural level [

14]. In a similarly layered, yet more management-orientated safety culture model, Vierendeels et al. [

26] also present different levels of safety culture adoption, being the outer technological layer with observable safety outcomes (injury rates, procedures, technology, individual behaviour, training). The mid layer is two-fold with the human domain about personal psychological factors (individual intentions, motivation, skills, abilities, knowledge, attitudes, behaviour, risk perception) and the organizational domain about the shared perceptions of safety (leadership, organizational trust, communication, transparency, management commitment). The third and inner layer of safety culture is then made of beliefs, assumptions, and values. These layers dynamically influence each other and must be understood holistically [

26].

1.3. Co-Creation

Co-creation means value creation through innovation and interaction, facilitating and experiencing actors, networking entities, and organizing and engaging aspects [

17,

18,

19]. It is thus active co-creation behaviour during physical, virtual, and mental processes that is the basis for translating co-creation processes into co-creation practices [

26]. Co-creation as a concept has also evolved to be connected to management aspects such as partnerships, learning, knowledge, participation, and networks. As the co-creation of value covers not only measurable, for example financial, value, but also intangible value such as social or ethical value [

8], co-creation is a relevant and interesting tool to apply to intangible workplace safety factors. In this sense, the process of co-creation generates value via knowledge sharing and mutual understanding. Thus, interaction is central to co-creation. Co-creation involves value-creation through interaction in for example facilitating and experiencing actors, networking entities, and organizing and engaging aspects. Interactional co-creation uses artifacts, persons, interfaces, and processes that result in experienced outcomes, agencing engagements, resourced capabilities, and structuring organizations [

18]. Consequently, essential parts of the co-creation process are dialogue to foster engagement, adaptability, exchange, interaction and access to transparent and reliable information to create meaning and a mutual understanding [

18,

27,

28]. Bangun et al. [

29] add dimensions to the co-creation term by employing the job demands-resources model. Job resources are organizational, social, psychological, or physical factors contributing to employees fulfilling their goals by encouraging individual learning and growth, job autonomy, work relationships, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and job support. From this perspective, co-creation is a multi-dimensional construct covering innovation, helping, and advocacy behaviours. Especially when considering that optimism and pro-social behaviour are significant moderators for employee engagement, which is an essential prerequisite for both co-creation and safety culture, it becomes clear that co-creation is a valuable approach to understanding organizational workplace safety [

29].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Industry Context, Research Project Description and Case Company Presentation

This section is about the industry-, research and case company context, because when working with case companies, it is important to pay attention to surrounding circumstances and the wider industrial, economic, political and societal context. Companies processing forest into products such as pulp, paper, sawn timber or other wood-based products shape the Swedish forest industry [

30], and those companies in the Swedish forest industry employ approximately 120,000 people [

31]. As mentioned in the introduction, the forest industry is one of the most dangerous sectors when it comes to workplace safety, occupational accidents and injuries [

5]. For this reason, the Swedish Work Environment Authority releases a growing number of reports, documents, and brochures that have an increasing focus on social work environment, safety culture, and co-creation, subsumed under the term systematic work environment and safety efforts [

32]. These materials aim to help practitioners, health and safety officers, and union representatives to actively incorporate and work with safety culture. Additionally, several laws and policies apply to workplace safety in the forest industry, of which the most fundamental one is the Work Environment Act. This law defines the right to a good work environment for all employees in Sweden and it states that the employer has the ultimate responsibility for leading the way towards a good work environment with the goal of reduced accident numbers and health risks [

33]. More specific, the Law for Organizational and Social Work Environment relates organizational and social work conditions in management, communication, participation, work division, resources and responsibilities with the goal to prevent bad working conditions in social and organizational aspects [

34].

The research conducted for this paper is part of a project called “Active Safety Culture”. The aim of this project is to increase safety in the forest industry by developing new approaches to create an active safety culture. In this context, Centralfonden, Stockholm, Sweden, a fund that promotes a sustainable working life for employees in forestry and the forest industry by focusing on occupational safety and health [

35], collaborates with Arbetsmarknadens försäkrings aktiebolag (Afa) Försäkring (Translated to Labour Market Insurance Company Limited), Stockholm, Sweden, active in insuring employees in Sweden when it comes to sickness, work injuries, work shortage, parental leave or death at work. Moreover, Afa Försäkring manages knowledge and capital from insurance activities and promotes preventive measures and support for research to improve occupational health [

36]. Centralfonden provides financing to the case companies, enabling them to invest resources into the research activity and the project, while Afa Försäkring funds the research itself. The companies being included in the project are, apart from the case company in this paper, another Swedish paper- and pulp mill as well as a Swedish sawmill company. The case company where data was collected at for this paper has a long history, dating back to the 17th century, where it was built as an iron mill and being converted to a paper mill in the mid of 19th century. The factory employs ca. 200 people and is now part of a holding company active in wood processing in Sweden. This exact case-company is chosen because, as it is part of the research project, it works actively and systematically with safety culture, which gives good access to participants who are able to share information that is relevant to the research aims.

The case company is and has been very active in fostering improved workplace safety through an active safety culture in collaboration with research, as the case company participated in different research projects, where a joint dialogue of case company and researchers is the basis for practically improving their workplace safety in management and operational questions. One of these projects was the so-called “a sustainable working life project” which started with 60 dialogues to assess the existing safety culture as well as internal activities performed at the case company between 2019 and 2022. Leadership development was key to boosting safety leadership which led to a higher engagement in safety activities, such as behavioural-based safety conversations and Gemba walks, as the partnering research team acted as coaches to 14 managers and supervisors. Building upon this basis, coaching of informal leaders was performed to extend safety leadership among informal leaders. This together with workforce workshops at the yearly “employee days” open discussions on how to improve safety and wellbeing of employees among all employees, aiming at fostering an inclusive safety culture where there is less “us and them” culture. Instead, the goal is that every employee sees themselves as a valuable contributor to safety culture in the organization. In their current safety culture work, the company recognizes the difficulties of changing any culture, and safety culture in particular, because of the underlying paradigm shifts that are necessary for changing the way of how an organization approaches safety. The organization aims to employ a different perspective, leaving behind a traditional rule- and compliance-based safety management style that concentrates on failures and accidents, because this often results in compliance-centred culture rather than an active and human-centred safety culture that encourages learning from successes.

2.2. Methodology

Because the proposed research is highly influenced by the practical consequences of safety meanings and knowledge of the people employed at the case company, and as researchers make sense of those practical realities via interpretation and reflection, the employed research philosophy can be described as a mix of pragmatism and interpretivism [

37]. An explorative research design was chosen because workplace safety has not yet been analysed in a forest industry context from a safety culture co-creation perspective, making the purpose of this research to investigate a phenomenon or issue that has not been clearly defined with the goal of gaining in-depth insights, uncovering patterns, and developing theories to address this knowledge gap [

38]. In this paper, an abductive approach [

39] was applied, as the theories and concepts of safety culture and co-creation in combination were taken as point of departure to explore mechanisms and driving forces of safety culture co-creation in order to investigate theoretical and practical implications of safety culture co-creation in the forest industry.

Sampling employed different sampling strategies to ensure that interview participants were able to provide extensive and deep information that is relevant to the research aim [

40]. The sampling strategy thus followed a mix of quota, purposive and opportunistic sampling [

37,

38]. Quota sampling was applied to define the initial sampling structure, namely that every shift team and every department should be represented in the dataset. Purposive sampling was used to include the employees having knowledge and experience in relation to workplace safety and safety culture that is relevant for answering the research question. At the same time, purposive sampling was used to generate a diverse dataset where perspectives from different ages, genders, and backgrounds are represented. Both quota and purposive sampling strategies were used in the planning phase of the data collection to determine the characteristics of the participating employees and the structure of the data collection process. Opportunistic sampling was then employed when actually conducting data collection, because the interview participants, teams and departments were not predetermined. Rather, the specific progress of interview conduction and actual participants were decided on spontaneously concerning availability and current workload when visiting the production site. In other words, interview participants were those persons that were present in the control rooms of each department when visiting the respective control rooms. Thus, the sampling in this stage was driven by the opportunities that present themselves during the visits on-site and can therefore be labelled opportunity-driven sampling.

The starting point of developing the data collection process was the intention to capture the current status of safety culture in the case company, for example in what is working well, what can be improved, what is important to the employees when it comes to safety culture etc. This is then the basis to enter a deeper discussion with the interview participants about workplace safety and safety culture. In the on-site study visits, semi-structured group interviews were held by one to two researchers with groups from five different shift teams in four different production departments and non-shift working teams in the office, and varying service and maintenance teams, for example electricians, mechanical maintenance or laboratory staff. By doing so, it was aimed to gain an as complete and diverse dataset as possible that is representative of the perspectives, opinions, and perceptions of the different individuals and teams at the whole factory. The HR Manager and the HSE Manager of the factory were partly present during most of the interviews as they also played a facilitating role by showing the interviewers around on the production site. This created legitimacy among the participants and added additional contextual information that elevated the interview depth. Possible concerns about biased results can be mitigated by the fact that the responses of the groups where the HR manager and HSE manager were present are not different from those groups where the HR manager and HSE manager were not present. The interviews were held in April 2024, and they took place in the respective departments’ control rooms or break rooms. Every interview lasted between 45 and 60 min. Group sizes varied between two and eight participants. In total, 30 group interviews were held with 136 participants. The number of participants represents more than half of the current staff of the case company, which mitigates risks of bias because of collecting data only at one case company. Also, the researchers opted for exploring the topic in-depth, which aligns with the research design and relatively under researched nature of the chosen topic, which justifies data collection at one distinct case company. Interview participants represented five different shift teams working morning, evening, and night shifts in four production departments and non-shift working teams in the laboratory, in mechanical, electrical and instrument maintenance as well as in the office. The interviews were not recorded; therefore, data was secured via notetaking by all three involved researchers. The notes were later joined into one document to facilitate holistic data analysis. To reduce the risk of missing information, the interviews were conducted, where possible, with two researchers present, of which one researcher asked questions and moderated the conversation, while another researcher listened and took notes of the interview contents.

The researchers opted for semi-structured interviews because this kind of data collection combines a certain structure with room to deepen the conversation in topics that come up during the interviews, allowing for adherence to the research aim while also remaining open for new thoughts and ideas from the interview participants [

39]. Moreover, this way of collecting data recognizes the discourse not only between interviewers and participants, but also between the participants themselves that develops during a focus group interview, which generates even deeper insights [

41]. Also, due to the goal of exploring safety culture co-creation, which is a highly collaborative and communicative notion that is enacted in groups, it is suitable to research such a phenomenon with the help of focus group interviews that encourage interaction and dialogue. Also, as it is aimed to understand mechanisms and driving forces of safety culture co-creation that happen in everyday work, it makes sense to interview focus groups that work together on a daily basis, thus being able to provide the desired relevant information.

Following a grounded theory approach, data analysis employs coding and thematic analysis to find overarching patterns and concepts that fit the organizational context this study is located in [

42]. The goal of utilizing this method for data analysis is to ensure and balance both scientific rigor and creativity at the same time. As abductive and qualitative interpretive analysis, this analysis method is about discovering 1st Order Concepts, 2nd Order Themes, and Aggregate Dimensions in the dataset. 1st Order Concepts are quite granular and keep proximity to the terms the data collection participants provide. Those concepts often appear in great numbers and with a certain fuzziness. Then, differences and similarities among the many identified categories can be recognized as the research progresses. Labels or specific phrases are then allocated to these categories while searching for deeper structures, meanings, and patterns in these labelled categories. This process results in finding 2nd Order Themes, which are more theoretical than practical. In this analysis step, special attention is given to identifying nascent concepts that have special significance or have not been covered by existing literature. Those themes and concepts are further aggregated into more theoretical and abstract Aggregate Dimensions. This process is visualized by building a data structure that shows how the researcher progresses in the analysis, from the raw data to underlying themes and patterns. The last step of the analysis is to bring emergent data, concepts and dimensions, and relevant existing literature together to find similarities and discrepancies when comparing the data insights with the literature. In this way, new concepts, antecedents, and continuations of existing theories can be derived. This last step is undertaken in the discussion chapter of this article.

3. Results

3.1. Individual Responsibility for Attitudes, Practices and Engagement in Communication and Continuous Improvement

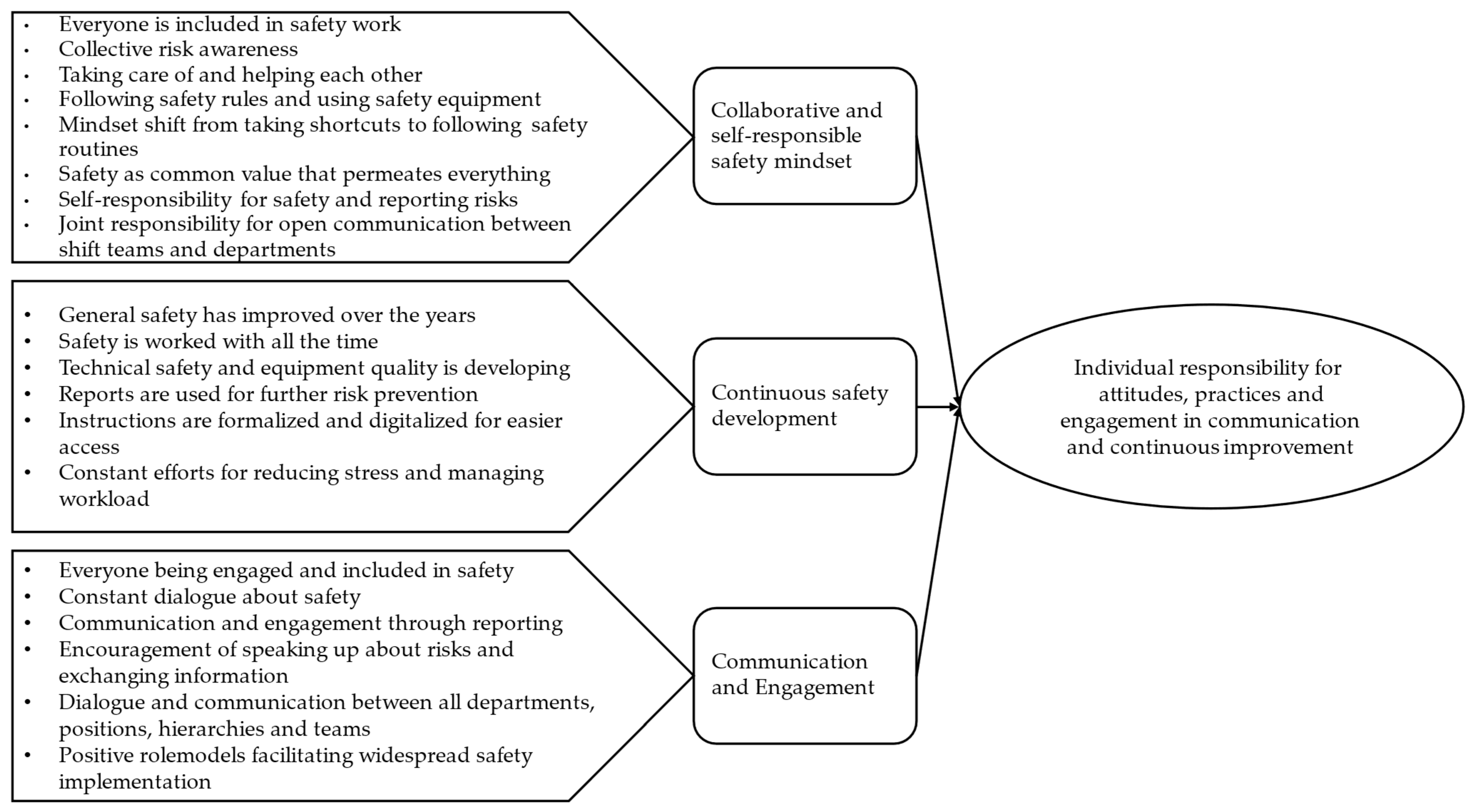

In the data, the weight of individual responsibility for attitudes, practices and engagement in communication and continuous improvement is an often-reoccurring dimension that is expressed in different themes and concepts (

Figure 1). First, on the one hand, participants highlight the importance of enacting self-responsibility by “not taking shortcuts” to avoid following safety routines and by “carefully using personal protective equipment”. On the other hand, a strong feeling of responsibility for the safety of colleagues is also mentioned, for example by stating that it is crucial to “help each other” and “speak up about risks and experiences with safety”. This helps to create a common understanding of safety as a core value via “agreeing on safety as the first priority in all work tasks”. Thus, a collective risk awareness, including everyone in daily safety practices, communication between shift teams and departments, following safety routines, reporting risks as well as taking care of each other. Consequently, there exists a theme of a duality of collaborative and self-responsible safety mindsets that mutually influence each other.

Second, it is underlined that the continuous development and improvement of workplace safety is an inherent aspect of safety culture co-creation. For example, interview participants claim that “in the past, we thought more about production, but now we prioritize safety”. Also, it is stated several times that “safety development goes into the right direction”, that “safety has to be as easy as possible” and that “there has been happening a lot in this realm” and that they “achieved a high safety standard” in comparison to the past. From this, it can be concluded that improvement of safety over time, constant safety work, systematic risk prevention through for example reporting and an enhanced quality of physical and technical safety measures is important to consider. As a result, a theme of continuous safety development can be observed n safety culture co-creation.

Third, the role of communication and engagement is presented as critical aspect of workplace safety. This can be seen in claims from interview participants like for example “we talk a lot about safety” or “it is important to create an open and critical discussion about safety”. The need for positive safety communication also becomes apparent in the wish for “highlighting what works well, we need more praise and good role models”. This theme is also reflected in statements such as “everyone needs to be involved in safety work and everyone need to be included” or “you should feel that you can influence workplace safety and that you can make a difference”. It is noted that everyone being active in safety work, creating a safe atmosphere to address safety issues, encouraging reporting of risks and acknowledging the positive influence of role models facilitating widespread safety implementation are aspects that foster engagement. As another side of the same coin, communication and dialogue are highlighted as an utmost important safety co-creation factor. Here, a constant, positive yet constructive and open dialogue about safety, exchange of information about risks as well as an increased communication between shift teams, departments and hierarchies can be regarded as most crucial.

3.2. Organizational Responsibility for Leadership Commitment, Information Dissemination and Active Risk Management

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

The second aggregate dimension is about the organizational responsibility for leadership commitment, information dissemination and active risk management (

Figure 2). In this regard, leadership communication and commitment is one of the two integral parts of this theme. It manifests in management prioritizing safety before production, providing timely, relevant and concrete feedback, investing in safety and providing preconditions for a safe work environment that enables employees to behave safely. Moreover, this theme consists of equal collaboration and communication between leaders and employees, where leaders take concerns of employees seriously and value the input of employees, which in turn leads to a trusting and respectful relationship. Open, systematic, and transparent communication that goes both ways between management and employees is also of great importance. This result is exemplified by utterances that underline the consequences if these aspects are not taken care of, like “leaders keep much information to themselves” or “there is no dialogue between employees and management”.

Another important theme is reporting, risk, analysis and safety management. The presence of accessible, targeted and relevant reporting systems, active and continuous risk analysis and safety management, reporting resulting in timely and efficient action, reporting as basis for further dialogue and the practical mitigation of reported risks are highlighted as crucial several times in the dataset. Again, especially when concentrating on negative statements by interview participants, the importance of the named concepts is shown by the consequences when they are not in place. Claims such as “risk reporting feels like a black hole, we do not get any feedback.” and “it feels like it is more important to report a lot than to report important things” are arguments for this result. But there are also positive statements underlining this observation, for example “it is important to report risks” and, apart from physical risks, “also reporting psychological and social safety problems” show that reporting, risk analysis and safety management are important themes for safety culture co-creation.

3.3. Practical, Relevant, and Continuous Training and Experience Sharing Through Active Talent Management

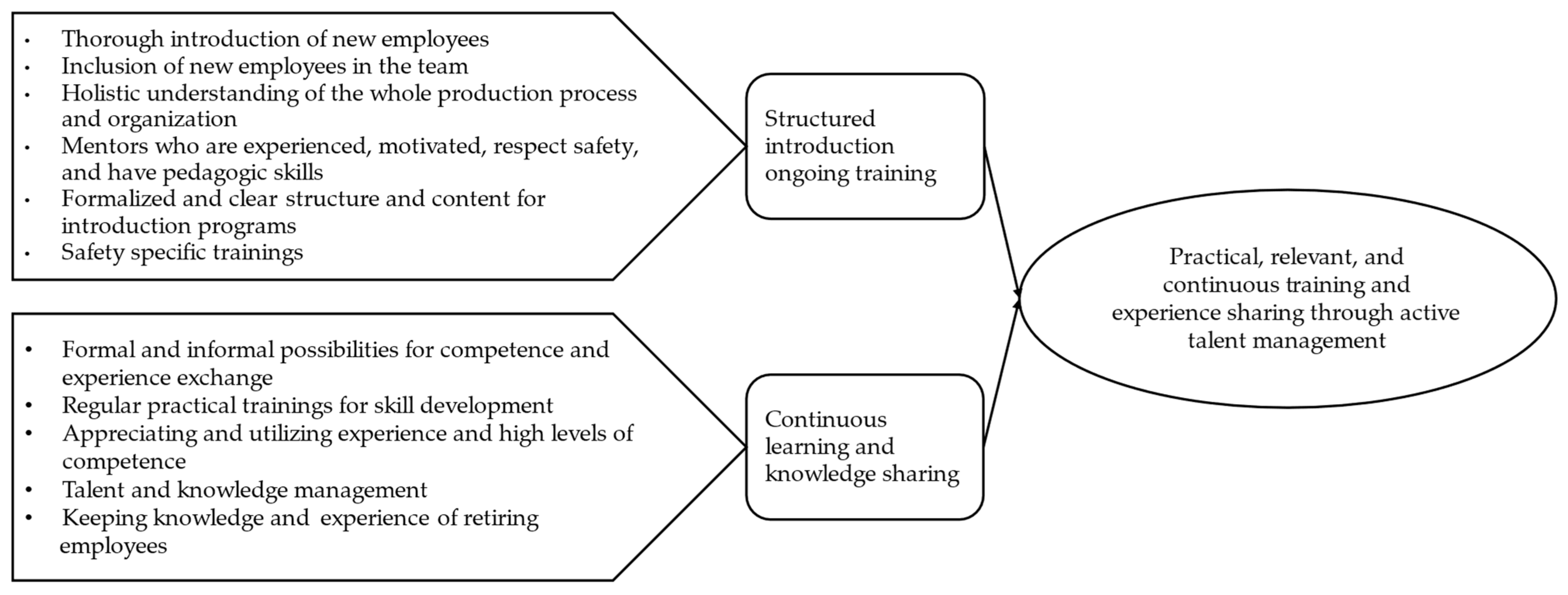

Safety culture co-creation also heavily relies on practical, relevant, and continuous training and experience sharing through active talent management (

Figure 3). An integral part of this is the structured introduction for new employees and ongoing training for experienced employees that have been in the organization for a longer time. This theme contains concepts such as a thorough and safety-sensitive introduction, the inclusion of new employees in the team as well as mentors that are experienced, motivated, safety-respecting and pedagogically skilled. This becomes clear when interview participants say that “you have to feel safe as a new employee”, but also when it is criticized that “today you start earlier with dangerous work tasks, that can work if you learn fast but that is not always the case”. Also, safety specific training and fostering a holistic understanding of the whole production process and organization among all employees as well as the formalization and structurization of introduction programs with clear content and timeline are important concepts in this realm. This is reflected for example in the following statements: “many accidents happen to those that have worked here for up to six months” or “everyone should get a walkthrough of the whole production process”.

When it comes to the theme of continuous learning, and knowledge sharing, the following concepts are recognized: providing formal and informal forums for competence and experience exchange between all employees, developing skill further through regular practical training and appreciating and actively utilizing experience and competence for safety work. In the data, those concepts can be found in the importance of “training critical situations”, difficulties to “find employees with the right competence” and the opinion that “experience should be valued and utilized”. All this is facilitated through a systematic talent and knowledge management approach. The importance of keeping the knowledge and experience of retiring employees is shown by utterances that highlight risks of not following a systematic approach to knowledge management, when “there is not much experience exchange, so that skills of experienced employees vanish when they leave the company”.

3.4. Safety Integration in Daily Operations in Relation to Physical and Psychosocial Work Environment Aspects

In the aggregate dimension about the integration of safety in daily operational processes in physical and psychosocial work environment aspects (

Figure 4), two themes can be derived from the data. The first is safety embedded in daily operations, which means for example that safety is an integral part of formal and informal gatherings at work, so that “safety is a part of every meeting and conversation”. It is also mentioned how important it is to always work in teams in a careful, foreseeing, calm and informed way that is embedded in a “respect for the machines and the risks they pose”. Additionally, it is critical that employees and management are aware of risks that cannot be fully eliminated in order to mitigate them actively, because “there are some situations and tasks that are riskier than others, and you have sometimes no possibility to improve this”. This makes clear, relevant and structured routines and procedures critical for physical work environment safety, because “there is a risk every time we go to work”. Thus, fast, effective and targeted problem solving is necessary that represents an organization-wide prioritization of safety in operational processes.

The second theme is about physical and psychosocial work environment aspects. The first contains for example safety management and routine development when it comes to handling physical risks such as traffic, pressure, chemicals, heat, moving parts and high voltage. Additionally, constant modernization efforts of machines and investments in high-quality equipment actively prevents physical safety risks, because “old machines increase the complexity and creates risks”. This makes investments in physical safety improvements as well as the accessibility and “usage of safety equipment” a crucial factor for safe physical work environments. It is also important to ensure a competent and sufficient workforce, because “a reduced workforce leads to more workload and stress”. This makes having sufficient skilled employees also a stress prevention tool. Consequently, the active and preventive management of stress and workload is also important, which is reflected in statements identifying that “the more you are in a hurry, the more is safety lost out of sight”. An open, respectful, appreciative and helping atmosphere to encourage discussions about critical and sensitive issues is also part of psychosocial work environment factors for safety culture co-creation. This contributes to “not only safety, but also wellbeing”, enabling employees “to feel safe and comfortable with the work tasks” because they can “feel safe to speak up about risks and ask questions”.

4. Discussion

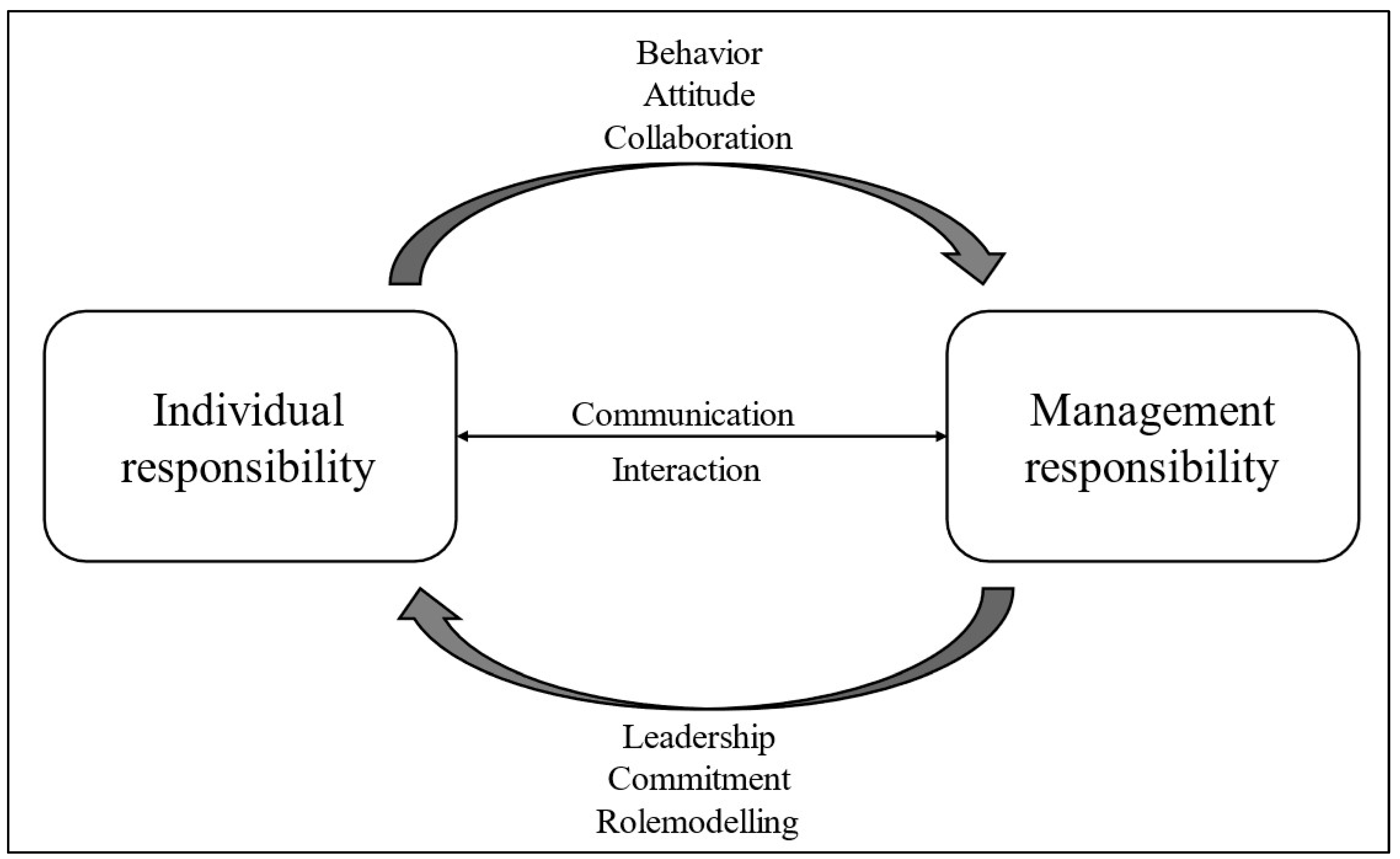

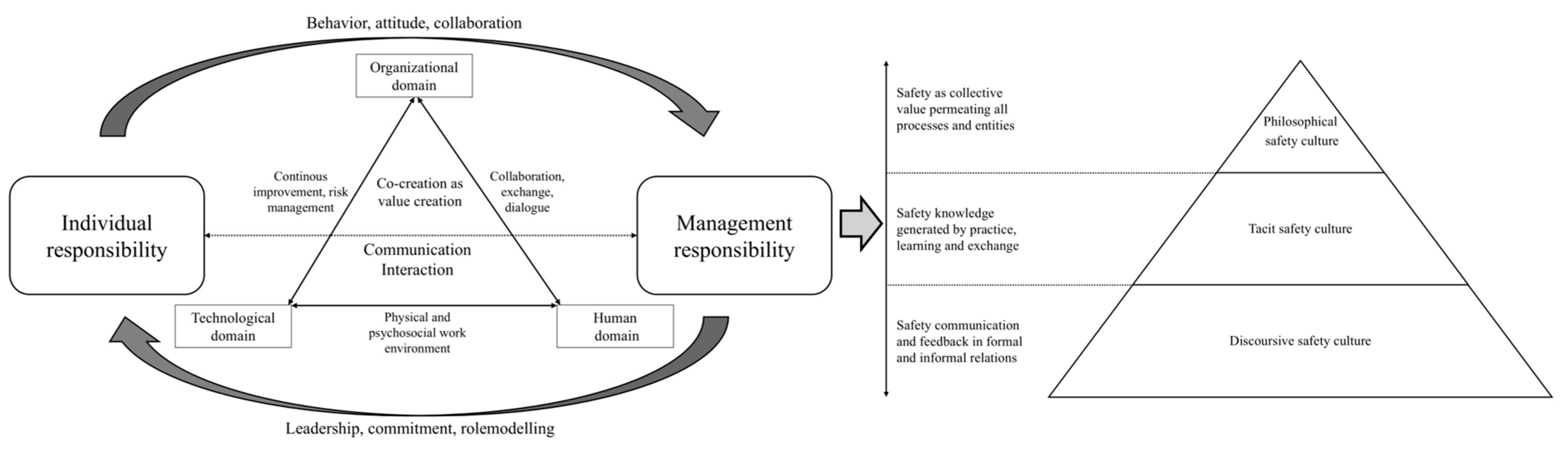

All in all, the importance of the interplay between individual and organizational safety responsibilities for safety culture co-creation becomes evident (

Figure 5). Individual responsibilities and organizational responsibilities mutually reinforcing safety culture co-creation mechanisms. Similarly, there is an interplay between individual and collective responsibilities in fostering safety culture. The impact of individual behaviour and safety responsibility is amplified when aligned with practices that are grounded in shared values. Thus, the holistic nature of safety culture co-creation incorporating aspects such as holistic engagement and inclusion is shown, like it can be found in theories emphasizing the synergy between individual actions and organizational systems on occupational safety [

12] or in approaches recognizing varying cultural dimensions [

16]. Moreover, this mechanism is described as individual domain in the duality of human and leadership safety domains [

26]. Related driving forces entail the fostering of an environment where individual accountability and actions are complemented by collective engagement through for example team identity, shared safety objectives, and informal knowledge and experience sharing.

In this sense, leadership and communication are identified to be crucial mechanisms for safety culture co-creation. Leadership commitment to safety, transparent, positive and accessible communication as well as a collaborative form of risk management are critical to enhance engagement of all involved employees and organizational entities. This finding shows parallels to the managerial lens of safety culture [

26] because leadership behaviours such as prioritizing safety or role modelling safe behaviour is found to shape shared safety perceptions. Vierendeels et al. [

26] locate these leadership orientated mechanisms in the mid layer of their safety culture adoption framework, together with the individual human safety culture domain. This highlights once again the complex relationship between individual and collective responsibilities as well as single employee and leadership levels. Expanding on the dynamic nature of safety culture co-creation, variations in safety culture perception result in the presence of sub-safety-cultures among different hierarchical levels, teams, departments and peer groups in the organization. This notion is reflected in the multidimensional mechanisms of integration, differentiation and fragmentation on safety culture [

14].

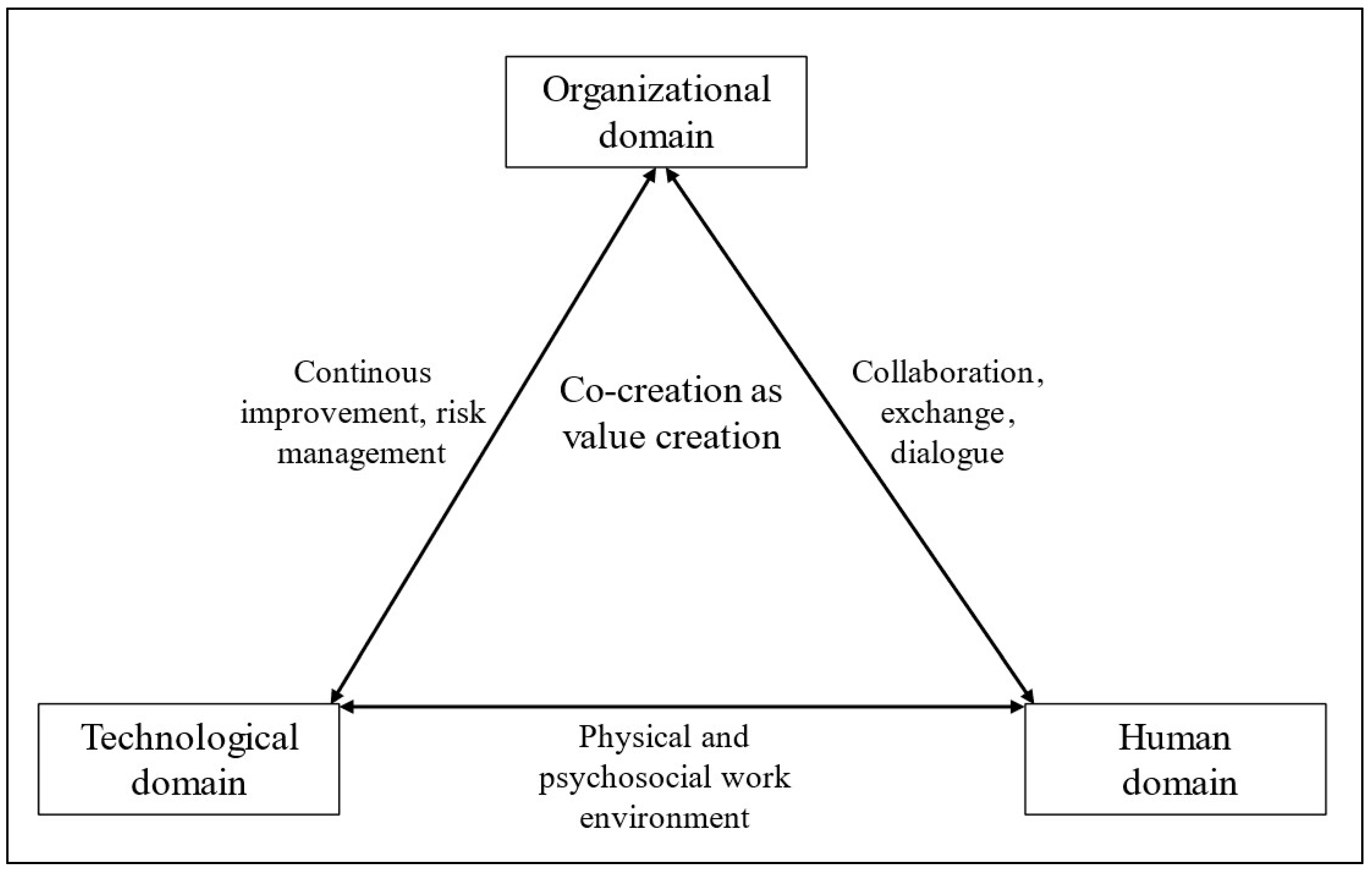

Another safety culture co-creation mechanism manifests in continuous improvement as basis for the evolution and development of workplace safety (

Figure 6). Here, it is essential to recognize the ongoing shift in prioritizing safety over production, the systematic prevention and management of risks as well as technical enhancements. This represents an integration of safety as value across the organization that is collectively prioritized before for example productivity or revenue. Thus, the notion of safety culture as evolving across different discursive, tacit knowledge and epistemological layers [

14] can be discovered here. Also, the gradual embedding of safety as a core value reflects an important safety culture co-creation mechanism in the form of progression from surface level safety adjustments to deeper philosophical shifts in safety as a value. This mechanism takes place in connection to driving forces that encourage iterative and holistic safety embeddedness in all organizational and cultural processes and entities, such as integrating mutual feedback loops and adopting flexible safety policies that evolve with organizational change.

Consequently, training, knowledge sharing and talent management are important driving forces for organizational learning and development. Also, a structured introduction of new employees, continuous learning and experience sharing between experienced and new employees as well as retaining knowledge of retiring and leaving employees are vital for safety culture co-creation. Related mechanisms include comprehensive, practical, continuous and relevant training programs, mutual peer mentorship schemes and systems for capturing and transferring organizational knowledge. These mechanisms have the goal to foster organizational learning and development by enhancing employee knowledge and skill. This observation resonates with the application of the job demands-resources model [

29] to occupational safety. In this approach, training and knowledge sharing can be understood as job resources that enhance safety behaviour significantly.

The balance between relevant and feasible safety measures in daily work tasks on the one hand and strategic and overarching safety work on the other hand impacts safety culture co-creation mechanisms and driving forces (

Figure 7). Thus, embedding and integrating safety in routine operations via addressing both physical and psychosocial work environment aspects is crucial for successful safety culture co-creation, because this encourages employees to speak up about safety issues, to translate organizational safety frameworks into action and to align daily work realities with organizational rules and routines. As co-creation is a form of joint value creation [

8,

17], it is vital to integrate safety across human, technological and organizational domains [

23]. Related driving forces include investments in modern and safe equipment and machinery for providing a physically safe work environment as well as fostering psychosocial safety through stress prevention, workload management and open communication channels.

In this regard, it is also highlighted that interaction and exchange play a central role as basis for successfully regulating and balancing these different human, technological and organizational domains together in safety culture co-creation [

18,

22]. Interactional mechanisms manifest in open dialogue, collaboration and mutual support as a basis for effective safety culture co-creation that permeates the whole organization. Shared engagement and responsibility underpin value-creation through holistic safety culture co-creation. Essential parts of the co-creation process are dialogue to foster engagement, adaptability, exchange, interaction and access to transparent and reliable information to create meaning and a mutual understanding of the discourse [

18,

28]. For this reason, important practices that facilitate these mechanisms are the utilization of participatory platforms to engage employees in decision-making processes, transparent and accessible safety updates as well as the creation of formal and informal safe spaces to discuss safety challenges.

When bringing all these findings together, it becomes clear that safety culture co-creation mechanisms are multifaceted as they span varying cultural dimensions, areas of responsibility and organizational levels and entities, impacting each other in dynamic, mutual and complex ways (

Figure 8). On the left side of

Figure 8, it can be seen that safety culture co-creation mechanisms take place between individual and management responsibilities. While individual employees engage in safety culture co-creation via safety behaviours, safety attitude and peer collaboration, management participates through leadership style and actions, managerial commitment to safety and role modelling safe behaviour. Communication and interaction mechanisms are at the heart of co-creation, and it can here be understood as joint value creation between organizational, human and technological domains. At this point, continuous safety improvement, systematic risk management, collaboration, exchange, dialogue and physical as well as psychosocial work environment foster safety culture co-creation.

On the right side of

Figure 8, the result of those safety culture co-creation mechanisms is depicted, namely that safety permeates all cultural layers ranging from discursive levels over tacit knowledge to philosophical cultural notions. At this point, informal and formal safety communication and feedback is the basis for embedding and generating safety knowledge through practice, learning and experience exchange. When safety is implemented in the named cultural layers, ultimately, safety is then a collective core value that permeates all organizational processes, relations and entities, building the basis for all activities from abstract and long-term strategic aspects to practical and short-term everyday operations.

5. Conclusions

In the data analysis, four different aggregate dimensions of safety culture co-creation were identified. The first, individual responsibility for attitudes, practices and engagement in communication and continuous improvement, highlights the impact of a collaborative and self-responsible safety mindset, continuous safety development as well as communication and engagement. The second aggregate dimension is organizational responsibility for leadership commitment, information dissemination and active risk management, illustrated by for example leadership communication and commitment as well as reporting, risk analysis and safety management. The third aggregate dimension is about practical, relevant and continuous training and experience sharing through active talent management, which is illustrated by the importance of continuous learning and knowledge sharing as well as a structured introduction and ongoing training. Fourth, the integration of safety in daily operational processes in physical and psychosocial work environment aspects was identified to be critical, with for example safety being embedded in daily operations as well as paying attention to different work environment dimensions.

Based on these results and together with relevant literature about the topic, key mechanisms and driving forces of safety culture co-creation were explored to provide a significant theoretical contribution. A key mechanism is the interplay between employee and leadership responsibilities and between individual and collective contributions, as safety culture co-creation relies on the interaction between for example individual adherence to safety routines and proactive communication, as well as leadership commitment and organizational information sharing. When individual actions and organizational circumstances are aligned by safety as core value, a mutually reinforcing mechanism is created that fosters holistic safety culture co-creation that involves individual accountability and collective engagement. In this mechanism, leadership and communication are key driving forces for shared safety perceptions, because they provide a way for managing dynamic safety cultures with variations across organizational levels, teams, and departments, necessitating mechanisms to manage safety culture integration, differentiation, and fragmentation across cultural and organizational dimensions. Another important mechanism is provided by continuous improvement activities that prioritizes safety over production via systematic risk management. This ensures that safety is integrated into daily operations in both physical and psychosocial work environments, which is in its turn a driving force for increased engagement for all employees in safety culture co-creation. A supporting mechanism is training and knowledge sharing, because it raises physical and psychosocial safety awareness and offers forums for interaction and communication about safety. Mentorship, structured onboarding, and knowledge retention enhance safety behaviours and organizational learning as they ensure organizational development and continuous improvement. To sum up, the most impactful safety culture co-creation mechanisms evolve around cross-sectional and interhierarchical interaction and communication, because these are shown to be the basis for holistic and dynamic safety culture co-creation.

These findings advance safety culture theory by providing insights into mechanisms and driving forces of how safety culture is created jointly. Future research avenues open up in investigating not only safety culture co-creation within organizations, but also between organizations, policy makers, communities and institutions, for example in the interplay between industrial realities and political assumptions about workplace safety. This would add additional actors to the co-creation process and provide wider insights into safety culture co-creation on varying societal levels. Also, a future research possibility lies in exploring the relationship between specific safety culture co-creation mechanisms and safety outcomes or safety performance, highlighting the impact of safety culture co-creation on measurable safety factors on a more nuanced level. Third, there is a need for a closer look on the central role of interaction and communication for safety culture co-creation. There, future research could focus on chances and challenges of how insights about communication and interaction can be utilized in practical implementation when it comes to active safety culture work.

Practical implications unfold in different dimensions. Practitioners can for example utilize the insights about interaction and communication being critical safety culture co-creation mechanisms for providing formal and informal forums for dialogue and collaboration across the organization for embedding safety as core value that permeates all organizational and cultural domains from strategy to daily operations. Recognizing safety culture co-creation as value creation could also help practitioners to shift their perspective from a focus on safety outcomes to a more holistic understanding of safety including intangible and anticipating safety factors with the potential to contribute to a more holistic and sustainable development of workplace safety. Additionally, the practical benefits of training and knowledge sharing becomes evident, illustrating pathways for practitioners to not only develop skills and competences in the workforce, but also to create inclusive possibilities for the workforce to engage in safety culture co-creation, which in turn contributes to organizational development. Moreover, the practical relevance of the duality of joint and individual safety responsibility becomes evident, highlighting the need for practitioners to actively manage accountability in individuals, teams, departments and hierarchies by for example leveraging the power of systematic and collaborative risk management that is based on the input from the whole workforce.