Abstract

The aim of the present work was to explore insights into the possibility of cultivating the mycelium of the edible basidiomycetes, i.e., Agaricus bisporus (J.E. Lange) Imbach, Lentinula edodes (Berk.) Pegler, and Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm. on wastes produced from lavender, sage, mint, and rose. To achieve this goal, we assessed the growth and development of strains on various substrates, a component analysis of the biomass of strains, initial essential oil raw materials after processing, and raw materials after exposure to the mycelium of basidial fungi strains. The wastes of essential oil production can be transformed with the help of edible basidiomycetes (A. bisporus, L. edodes, P. ostreatus) into a valuable fodder product enriched with proteins and vitamins and with good organoleptic properties. The best of the tested substrates was the green mass of mint after successive distillation and extraction. The conversion of solid waste from lavender, rose, sage, and mint processing depends on the types of strains. The high accumulation of octen-3-ol (up to 1.38 g/kg of the substrate) by P. ostreatus was confirmed by its organoleptic evaluation. The results suggested the cultivation of edible mushroom mycelium on the solid waste of mint, lavender, and sage processing could produce high-grade (enriched in proteins and vitamins) biomass for the purpose of fodder. These by-products could serve as a basis for the creation of cultivation technology for champignon, shiitake, and oyster mushrooms as food products using secondary resources of essential oil production.

1. Introduction

Recently, due to the shortage and increasing cost of protein (especially of animal origin), a great deal of attention has been paid to the processing of lignocellulosic materials into high-protein feed and food additives with the help of various microorganisms [1,2,3]. This is explained by the high growth and protein production rates of microorganisms that are several times higher than that of animal- and plant-based protein.

Saprophytes are important because they decompose organic matter in the environment [4]. Most mushrooms are produced in wood due to many fungi that are tree symbionts or decayers of tree tissues. Therefore, the development of farming techniques to utilize hardwood trunks and sacks depends on the types and the quality of mushrooms as ecosystem decomposers [5]. At present, sawdust and hardwood logs from industrial and agricultural by-products are used in the production of various types of mushrooms [6].

Over the past 30 years, from 1990 to 2020, the output of mushrooms on a worldwide scale has expanded by 13.8 times, reaching 42.8 million tons [7]. The productivity rates of mushrooms such as Lentinula edodes, Pleurotus spp., Auricularia spp. and Agaricus bisporus are high [8]. The fresh mushrooms contain many of the essential amino acids, antioxidants, and elements and are ecologically safe. The cultivation of mushrooms for commercial production is seeing rapid growth (approx. 85,000 metric tons per year) in the Russian Federation; however, up to 93% of the world’s mushrooms are cultivated in China [7]. Moreover, the production of mushrooms is rapidly increasing in various countries. The production is not dependent on the seasons or climatic conditions, as the mushrooms can grow in dedicated cultivating facilities throughout the year [9]. These cultivating facilities are effective. Another important advantage is that some species of microorganisms can be cultivated on plant substrates, resources that are large and stable because they are replenished annually [10,11,12,13]. Among used substrates, wheat straw, olive pruning residues, tea leaves, and wetland vegetative species are promising [14,15].

Over the last few decades, the studies on flavor-forming basidial mushrooms for obtaining products enriched with nutrition and biologically active substances have significantly intensified and resulted in a high demand [16,17,18]. Modern approaches can be applied to the development of waste-free technology for specifically essential oil crop raw materials, which are usually thrown away after the oil extraction [19]. The most common large-tonnage raw materials for the production of natural aromatic products are plants such as lavender, sage, mint, and rose. Therefore, the waste generated after essential oil production is significant and could be recognized as a promising material for obtaining protein products. In Russia, the annual volume of such wastes is 160–220 thousand tons [20]. Thus, the use of these wastes is of particular relevance in Russia and the world [21].

Fungi of the genera Pleurotus, Agaricus, and Lentinula are active decomposers of the lignocellulose complex of substrates [12,22,23]. In the process of biodegradation, these fungi secrete a complex of enzymes, the most important of which are hydrolytic and redox enzymes capable of hydrolyzing polysaccharides and degrading lignin [24]. In many ways, the degree of degradation of the components of plant raw materials is affected by the type of substrate, the type and strain of fungi, as well as the duration of cultivation [25].

This study aimed to find the possibility of cultivating mycelium of Agaricus bisporus (J.E. Lange) Imbach, Lentinula edodes (Berk.) Pegler, and Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm. on lavender, sage, mint, and rose processing wastes of essential oil production. The growth and development of these strains on various substrates, a component analysis of the biomass of strains, the initial essential oil raw materials after processing, and the raw materials after exposure to the mycelium were assessed.

2. Materials and Methods

Mushroom cultivation. Strains of basidiomycetes were obtained from the collections of N.G. Kholodny Institute of Botany (Ukraine), D.K. Zabolotny Institute of Microbiology and Virology (Ukraine), and G.K. Skryabin Institute of Biochemistry and Physiology of Microorganisms (Russia): Agaricus bisporus (J.E. Lange) Imbach IBK 459, Lentinula edodes (Berk.) Pegler IBK 55, Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm. IMV F1300, VKM F2008 (IBK 109).

The cultivation of these basidiomycete strains (maintenance of the working collection, cultivation of inoculum) was carried out on known media [21]. The strains were maintained on beveled potato dextrose agar. The cultures were inoculated for 72 h at 28 °C on the surface of soy sugar agar (g/L): sucrose, 15.0; soybean meal, 20.0; corn extract, 10.0; potassium pyrophosphate, 1.0; agar, 20.0; and pH 6.7–6.8. Furthermore, the cultures were transferred into flasks on a rocker (100 rpm) following the deep method for 5 days in liquid 6 B0 wort when the inoculum biomass reached 10.0 g/L.

The solid-phase cultivation was carried out on various plant substrates—waste products of floral and herbaceous raw material processing with a layer of 10–15 cm to prevent evaporation of volatile fragrant substances. In the experiments, the main substrates for growing mycelium were the plant materials of Rosa spp., lavender (Lavandula vera D.C.), clary sage (Salvia sclarea L.), and peppermint (Mentha piperita L.) after the extraction of target products using distillation and/or extraction in plant and laboratory conditions. The substrate was brought to 60% humidity by adding water. These materials were sterilized with sharp steam for 30 min at 0.1 MPa. After cooling, the inoculum was inoculated to 10% of the medium (substrate) volume. Plant substrates for inoculation with cultures were placed in glass containers with a volume of 500 mL in 10 repetitions. At the same time, the ratio of carbon and nitrogen in the production waste of essential oil raw materials after their primary processing was not considered.

The growth of the strains was evaluated by the rate of overgrowth of the substrate and the nature of the formation of aerial and substrate mycelium. The degree of growth index was estimated visually on a 6-score scale: 0 points—no visible growth; 1 point—up to 10% (very small); 2 points—11–30% (small); 3 points—31–50% (medium); 4 points—51–70% (large); 5 points—71–90% (very large); and 6 points—91–100% of substrate surface and volume penetrated by basidiomycete hyphae. White hyphae are clearly visible on dark culture material. Upon completion of incubation, the studied strains on essential oil plant waste were dried on framed screen racks protected from direct sunlight using a convective method at a temperature of the heat-carrier air of 40 °C to a residual moisture content of 10%.

Component Analysis. The indicators shown in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 were determined from cultures grown in potato dextrose broth. During cultivation on liquid nutrient media, the biomass (mycelium) of the fungus was separated by filtration. Extraction of aroma-forming compounds was carried out using extraction and distillation methods [26]. For quantitative determination of essential oil, the European Pharmacopoeia method was used [27]. The determination of the component composition of the extracted oil was carried out using Chrom-5, Crystal 2000 M, and Perkin Elmer Clarus 680 chromatographs with a flame ionization detector on a polar column [28]. Five samples of each strain were taken for analysis.

The determination of chemical composition and sample preparation [29,30] were carried out using the following methods: skimmed residue in Soxhlet apparatus—fat content [31]; titration in the Kjeldahl apparatus—protein content [32]; phosphorus content—by ashing according to spectrophotometry at 670 nm [33]; calcium and potassium content—using atomic absorption spectrometry [34]; and fiber content—according to Genneberg and Shtoman in CINAO modification [1]. Ash, ascorbic acid, and tocopherol contents were determined according to the State Pharmacopoeia of the Russian Federation [35]. All measurements were performed in five-fold analytical replications.

The amino acid was extracted using capillary electrophoresis [36,37]. At least two electropherograms were recorded for each solution. The spectrophotometric method was used to quantify chlorophyll and carotenoids in the raw material. For this purpose, 5.0 g of raw material (precise weight, degree of crushing—0.5 mm) was placed in a 100 mL flask and extracted with 25 mL of extractant: hexane, crude hexane, and ethyl alcohol 95% under stirring for 1.5 h. The suspension was filtered through a paper filter. A total of 1 mL of the extract was placed in a 25 mL volumetric flask and topped up with the solution to the mark. The optical density of the sample was determined on a spectrophotometer SF-104 (spectral range of wavelengths, nm 190–1100; visible range—tungsten halogen lamp, UV range—deuterium lamp) at a wavelength of 450 nm (for carotene) and 664 nm (for chlorophyll) in a cuvette with a layer thickness of 10 mm relative to the extractant: hexane for carotene and ethyl alcohol for chlorophyll. Purified water was used as a control solution [38,39,40]. Mathematical data processing was carried out using the STATISTICA 10.0 software package. The results are presented in the format “mean ± standard deviation”. Multiple comparisons of the studied parameters were carried out in the framework of a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the Scheffe post-hoc test as well as the Duncan test. The critical level of significance (p = 0.05) was adjusted, if necessary, with the Bonferroni correction for multiplicity.

3. Results

Basidiomycete cultures are promising for the production of natural food flavorings because they are capable of accumulating industrially important and biologically active metabolites (Table 1). These types of mushrooms were of special interest due to volatile fragrant substances (aroma), which are caused by aliphatic 8-carbon compounds (1-octene-1-ol, 1-octene-3-one, 1-octene-3-ol, 3-octanol, etc.), some pyrazines, and pyrroles.

Table 1.

Flavor evaluation results of the basidiomycete species studied.

Table 1.

Flavor evaluation results of the basidiomycete species studied.

| Taxonomic Position | Strain | Synthesized Volatile Fragrance Substances | Smell | Aromatic Product Accumulation, mg/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agaricus bisporus (Agaricaceae) | IBK 459 | 3-methylbutanol, 3-octanone, 1-octene-3-one, 3-octanol, 1-octene-3-ol, furfural, benzaldehyde, phenylacetaldehyde, benzyl alcohol | severe mushroom | 70.3–230.0 |

| Lentinula edodes (Ompalotaceae) | IBK 55 | lentionine, 1-octene-3-ol, 1-octene-3-one | mushroom | 46.7–101.9 |

| Pleurotus ostreatus (Pleurotaceae) | IMV F1300 | 1-octene-3-ol, 1-octene-3-one | mushroom | 95.3–101.5 |

| VKM F2008 | 163.0–210.4 |

Note. Accumulation of aroma-forming compounds was determined in the culture liquid of the producer.

The ANOVA made it possible to establish that the species affiliation of the strain influenced the levels of protein (F = 5.026; p = 0.03; the power of influence according to Snedekor—18.69%) and fiber (F = 4.829; p = 0.03; the power of influence according to Snedekor—17.75%) in the biomass; however, there were no significant differences in the content of protein, fat, fiber, ash, potassium, calcium, and phosphorus between the biomass samples of different basidiomycete species (Table 2).

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the biomass of the studied basidiomycete species, %.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the biomass of the studied basidiomycete species, %.

| Strain | Protein | Fat | Fiber | Ash | Potassium | Calcium | Phosphorus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBK 459 | 35.6 ± 4.7 | 6.7 ± 3.3 | 4.5 ± 1.8 | 6.5 ± 2.1 | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 0.3 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| IBK 55 | 20.9 ± 7.1 | 3.9 ± 1.7 | 7.4 ± 1.3 | 5.6 ± 2.1 | 4.2 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| IMV F1300 | 27.7 ± 1.8 | 2.9 ± 1.9 | 7.3 ± 1.2 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| VKM F2008 | 29.4 ± 3.4 | 5.5 ± 1.6 | 9.5 ± 2.0 | 8.7 ± 1.5 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.4 |

An analysis of the amino acid composition of the biomass showed that the content of alanine and methionine did not depend on the strains of basidiomycete, and the concentration of other essential and non-essential amino acids was determined to some extent by the species of fungi (Table 3). Thus, the proportion of glycine was higher in strain IBK 55 than in IBK 459 (p = 0.006), and no differences were found between the other strains. The level of proline in samples of strain IBK 459 was lower than in samples of strain IBK 55 (p = 0.002) and IMV F1300 (p = 0.002). The contents of serine, tyrosine, lysine, phenylalanine, threonine, leucine-isoleucine, histidine were higher in strains IMV F1300 and VKM F2008 than in IBK 459 and IBK 55; no differences were found between pairs of strains IBK 459 and IBK 55, and IMV F1300 and VKM F2008. The proportion of valine in the biomass of strains IBK 459, IMV F1300, and VKM F2008 was higher than that of IBK 55 (p = 0.005, p = 0.001, and p = 0.0004, respectively). The arginine content consistently increased in the series IBK 459 → IBK 55 → IMV F1300 → VKM F2008.

Table 3.

Amino acid content in the biomass of the studied basidiomycete species, %.

Table 3.

Amino acid content in the biomass of the studied basidiomycete species, %.

| Amino Acid | IBK 459 | IBK 55 | IMV F1300 | VKM F2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Essential amino acids | ||||

| Glycine | 0.92 ± 0.14 | 1.45 ± 0.13 | 1.10 ± 0.10 | 1.19 ± 0.11 |

| Proline | 0.76 ± 0.12 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 1.84 ± 0.17 | 1.93 ± 0.18 |

| Alanine | 1.99 ± 0.18 | 1.67 ± 0.15 | 2.01 ± 0.12 | 2.10 ± 0.21 |

| Serine | 0.94 ± 0.08 | 1.45 ± 0.12 | 2.24 ± 0.21 | 2.43 ± 0.23 |

| Tyrosine | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 1.75 ± 0.13 | 1.67 ± 0.16 |

| Essential amino acids | ||||

| Lysine | 1.07 ± 0.10 | 1.34 ± 0.11 | 3.76 ± 0.34 | 3.87 ± 0.35 |

| Valine | 2.32 ± 0.20 | 1.45 ± 0.12 | 2.60 ± 0.20 | 2.90 ± 0.25 |

| Phenylalanine | 0.85 ± 0.10 | 1.11 ± 0.10 | 2.03 ± 0.18 | 2.10 ± 0.20 |

| Methionine | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± 0.03 |

| Threonine | 1.07 ± 0.09 | 1.34 ± 0.11 | 2.93 ± 0.44 | 3.03 ± 0.60 |

| Leucine & Isoleucine | 1.96 ± 0.17 | 3.00 ± 0.31 | 4.85 ± 0.45 | 5.48 ± 0.51 |

| Histidine | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.56 ± 0.05 | 2.91 ± 0.21 | 2.97 ± 0.25 |

| Arginine | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 1.56 ± 0.14 | 5.60 ± 0.06 | 6.07 ± 0.05 |

| Sum | 8.93 ± 0.82 | 10.70 ± 1.00 | 25.00 ± 1.89 | 29.77 ± 2.11 |

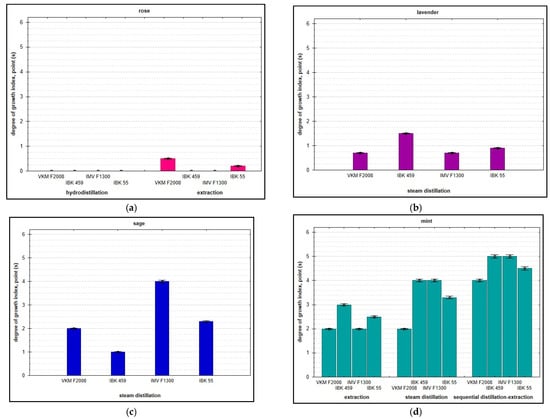

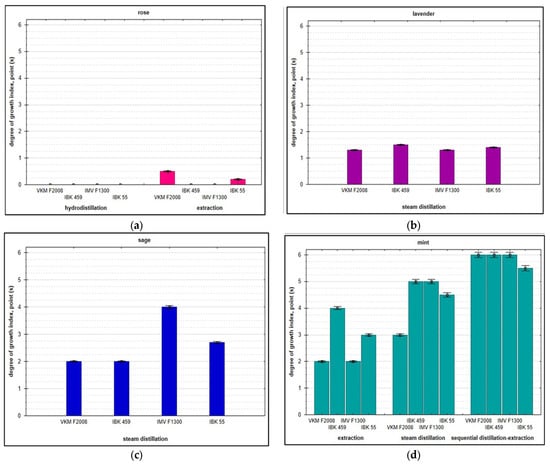

The bioconversion of the solid processing waste of rose, lavender, clary sage, and peppermint into valuable products by cultivating mycelium of edible basidiomycetes was carried out at two humidity modes in the cultivator. The results are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Degree of mycelium development (ordinate axis—6-point evaluation) of A. bisporus, P. ostreatus, and L. edodes on wastes from processing of floral and herbaceous essential oil raw materials at an air humidity of 50%: rose (a); lavender (b); sage (c); and mint (d).

Figure 2.

Degree of mycelium development (ordinate axis—6-point evaluation) of A. bisporus, P. ostreatus, and L. edodes on wastes from processing of floral and herbaceous essential oil raw materials at an air humidity of 100%: rose (a); lavender (b); sage (c); and mint (d).

Studies have shown that the utilization of solid wastes from the processing of lavender, sage, and mint is possible through biotransformation by basidiomycetes fungi depending on their species identity, and there is a tendency of strain specificity. The best nutrient substrate for mycelial development under conditions of 100% relative humidity was the mint plant material after steam distillation and subsequent extraction. After 2 weeks of incubation, the substrate was completely permeated with white threads—hyphae—and had a distinct mushroom aroma. However, the studied strains showed a high growth rate (2-fold higher) when utilizing clary sage waste after extraction: rapid germination of mycelium to the full depth of the substrate, abundant formation of aerial mycelium, and intensification of biosynthetic activity within one week.

During the solid-phase cultivation of strains on sage processing waste, it was noted that the yield of ether extract and octen-3-ol significantly increased in the series IBK 55 → IBK 459 → IMV F1300 → VKM F2008 (Table 4). The high level of accumulation of octen-3-ol (the main component responsible for the smell of edible mushrooms) during the cultivation of the P. ostreatus strains was confirmed by the organoleptic evaluation of cultures.

Table 4.

The biosynthetic activity of basidiomycete strains in solid-phase cultivation.

Table 4.

The biosynthetic activity of basidiomycete strains in solid-phase cultivation.

| Substrate | Strain | EE Yield, mg/kg of Substrate | Octene-3-ol Yield, mg/kg of Substrate | Content of Octene-3-ol in EE, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pleurotus ostreatus | ||||

| SWE | IMV F1300 | 580.0 ± 30.0 | 570.0 ± 30.0 | 98.2 ± 3.1 |

| SWE | VKM F2008 | 1450.0 ± 50.0 | 1380.0 ± 50.0 | 95.1 ± 3.4 |

| Agaricus bisporus | ||||

| SWE | IBK 459 | 490.0 ± 20.0 | 420.0 ± 20.0 | 85.7 ± 4.1 |

| Lentinula edodes | ||||

| SWE | IBK 55 | 310.0 ± 10.0 | 240.0 ± 10.0 | 73.4 ± 3.2 |

Note. EE—ether extract, SWE—sage waste after extraction.

The studied strains of basidiomycetes in deep culture also accumulated large amounts of biomass, for example, the biomass of P. ostreatus strain IMV F1300 reached 16 g per 1 kg of the substrate within 6 days. The level of accumulation of aroma-forming compounds directly depends on fungi biomass: the A. bisporus strain IBK 459 synthesized 30.0 mg/kg of essential oil within 3 days at a biomass of 2.34 g/kg and after 6 days at a biomass of 11.86 g/kg produced 41.4 mg/kg of essential oil and 262.0 mg/kg of extract. The mycelial mass of edible mushrooms preserved their flavor after drying during long-term storage (up to 10 years), as well as during cooking, in particular, by boiling for 10–15 min. A comparative analysis of the chemical composition of essential oil plant raw materials after their primary processing showed that rose was superior in protein content to lavender (p = 0.006) and sage (p = 0.003), and mint occupied an intermediate position (Table 5). The lowest content of fat (1.6 ± 0.2%) was noted in sage samples compared to other producers. The lowest content of fiber was found in mint samples. The total amount of inorganic substances (ash residue) in the samples of the studied producers was approximately the same (no differences were found between the samples); however, the content of individual minerals in different producers varied. Thus, the level of potassium in the samples of mint was higher than in the samples of rose (p = 0.0002), lavender (p = 9.71 × 10−5), and sage (p = 0.001). Differences were also found between the samples of lavender and sage (p = 0.005). In terms of calcium content, rose and mint samples were the leaders, significantly surpassing lavender (p = 0.0004 and p = 0.001, respectively) and sage (p = 0.0006 and p = 0.002, respectively). The proportion of phosphorus in rose (p = 0.002) and mint (p = 0.006) samples was higher than in lavender samples. Differences in carotene content were established for samples of rose and sage (p = 0.005).

Table 5.

Chemical composition of essential oil plant raw materials after primary processing, %.

Table 5.

Chemical composition of essential oil plant raw materials after primary processing, %.

| Producer | Protein | Fat | Fiber | Ash | Potassium | Calcium | Phosphorus | Carotene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential oil rose | 16.0 ± 2.0 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 40.2 ± 1.0 | 10.0 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.21 ± 0.20 | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.05 |

| Peppermint | 13.6 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 22.9 ± 2.0 | 11.1 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 1.08 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.82 ± 0.10 |

| Lavender | 11.4 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 37.4 ± 2.0 | 9.2 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.80 ± 0.10 |

| Clary sage | 11.0 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 30.5 ± 2.0 | 11.3 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.60 ± 0.05 |

The feeding value of secondary plant wastes of flower and herbaceous raw materials after the cultivation of basidiomycetes also depends on the strain according to some studied parameters. The level of vitamin C in VKM F2008 samples was an order of magnitude higher than in IBK 459 (p = 0.003), IBK 55 (p = 0.004), and IMV F1300 (p = 0.003). The content of tocopherol in samples of strains IMV F1300 and VKM F2008 significantly exceeded that of strains IBK 459 and IBK 55 (Table 6). No other differences were found between the strains.

Table 6.

Nutritional value of secondary plant wastes of floral and herbaceous raw materials after cultivation of A. bisporus, L. edodes, and P. ostreatus, %.

Table 6.

Nutritional value of secondary plant wastes of floral and herbaceous raw materials after cultivation of A. bisporus, L. edodes, and P. ostreatus, %.

| Substrate | Strain | Protein | Vitamin C | Carotinoids | Tocopherols | Phosphorus | Chlorophyll |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LWD | IBK 459 | 23.49 ± 9.21 | 0.010 ± 0.008 | 0.27 ± 0.24 | 0.077 ± 0.015 | 0.61 ± 0.11 | 1.80 ± 0.26 |

| SWE | IBK 55 | 16.97 ± 0.95 | 0.043 ± 0.018 | 0.38 ± 0.28 | 0.017 ± 0.006 | 0.80 ± 0.17 | 2.88 ± 1.68 |

| MWDE | IMV F1300 | 18.63 ± 6.45 | 0.011 ± 0.004 | 0.31 ± 0.24 | 0.817 ± 0.215 | 0.47 ± 0.05 | 4.29 ± 2.69 |

| RWE | VKM F2008 | 22.40 ± 6.57 | 0.410 ± 0.160 | 0.45 ± 0.34 | 0.907 ± 0.315 | 0.41 ± 0.07 | 0.06 ± 0.04 |

Note. MWDE—mint waste after distillation and subsequent extraction; RWE—rose waste after the extraction; LWD—lavender waste after distillation; SWE—sage waste after extraction.

The results of the analysis of the nutritional value (composition, i.e., the content of protein, vitamins, phosphorus, etc.) of secondary plant wastes after the cultivation of mushroom mycelium on them indicate an increase in their quality in terms of some indicators (Table 5 and Table 6). Thus, the bioconversion of residues from the processing of rose (p = 0.001352), mint (p = 0.0001705), lavender (p = 0.0001714), and sage (p = 0.0002144) led to an increase in the level of phosphorus by 2–5 times. In samples of lavender (p = 0.008) and sage (p = 0.0001459), after processing, the protein content increased by 1.5–2 times. However, the level of carotenoids decreased after bioconversion by about 2.5–3 times in rose (p = 0.003971), mint (p = 0.0009932), and lavender (p = 0.0008634) samples.

4. Discussion

It is known that some basidiomycetes (mushrooms) under deep cultivation can be used in the food industry to produce natural flavors with a mushroom smell [41]. The mushroom feed additive contains aromatic substances that produce a pleasant smell and thus improve organoleptic properties and consumption. Mushroom protein with an amino acid composition that complies with FAO standards is easy to digest without pretreatment. Other advantages of mushrooms should also be noted: a significant amount of mineral salts of potassium, phosphorus, iron, and calcium; the presence of vitamins (in particular, carotene up to 0.01%) that are not destroyed by physical and chemical exposure; and the content of several biologically active substances that affect metabolic processes (reduce blood cholesterol levels) and have therapeutic properties [42,43,44,45].

A higher content of octen-3-ol, as the main component responsible for the smell of edible mushrooms, was observed during the solid-phase cultivation of P. ostreatus strains (IMV F1300, VKM F2008) compared to strains of A. bisporus and L. edodes (Table 4) [9]. According to the present results, the content of the sulfur-containing amino acid methionine in the biomass of the studied strains is 0.31–0.35% (in terms of protein in champignon—0.9%, in shiitake—1.6%, in oyster mushroom—1.2–1.3%). Significant increases in the protein content during the bioconversion of all the studied types of solid waste by at least 1.4 times (Table 5 and Table 6) were found in this study. The bioconversion of the protein–carbohydrate complex of plant substrates, carried out by fungal mycelium, is a multi-stage process. In our experiment, under the influence of the mycelium of the studied strains, mint raw materials underwent the greatest destruction after successive distillation and extraction. During biotransformation, not only cellulose (cellulose) but also other carbohydrates (mono-, di-, oligosaccharides) can act as a source of carbon.

In some studies, it was found that P. ostreatus and P. cystidiosus grown in corncob, sugarcane, substrates, and sawdust had an increased fruiting body weight; some important minerals such as calcium, potassium, magnesium, and zinc are also reported at high content in P. ostreatus and P. cystidiosus [46]. All of the tested mushrooms (A. bisporus, L. edodes) had minimal Na content; however, P. ostreatus had the smallest amount. Because of the excessive K and reduced Na concentrations, the mushrooms may supplement human nutrition, ensuring that patients obtain sufficient amounts of K and Na. For example, the selenium content of A. bisporus may increase consumers’ access to selenium. These results show that there is no toxicological risk and that the Cd and As concentrations in these strains of mushrooms are comfortingly minimal, and a total of 98–99% of their components are four elements (K, P, Ca, and Mg), whereas the other elements contribute only 2–3% [47].

The additional lignocellulosic residues such as wheat straw and rice husk, which were supplemented with corn and sunflower oil, were employed to grow edible P. ostreatus and P. eryngii. In this combination, high levels of mycelium growth were recorded. Both Pleurotus species are capable of producing large amounts of lipase, and nitrogen and calcium sources promote enzyme synthesis, especially laccase production [48]. In other studies, tea waste and peat were used to increase Agaricus quality and its mineral composition, i.e., sodium, potassium, zinc, copper, iron, and calcium [49]. In recent work, it was found that olive oil waste substrate also improved the quality of various mushroom species, such as Agricus and Pleurotus [50].

Of particular interest is the change in the content of various components of plant substrates during cultivation. Thus, the bioconversion of rose, mint, lavender, and sage processing wastes led to a significant increase in the level of phosphorus by 2–5 times and a decrease in the amount of carotenoids by 2.5–3 times. The nutritional value of secondary solid waste was increased by strain-specific indicators of the content of vitamins C and E, which indicates the need to select destructor strains according to a combination of biotechnologically important properties.

5. Conclusions

For the first time, the possibility of recycling waste from essential oil production to obtain new natural products was studied. Basidial cultures were screened to select the most biotechnologically promising producers. The possibility of using rose, lavender, sage, and mint plant raw materials by mushrooms of the genera Pleurotus, Agaricus, and Lentinula after the materials’ primary processing is shown. For the biotechnology of feed products of fungal origin, four strains (IBK 459, IBK 55, IMV F1300, VKM F2008) have been proposed, differing in the compositions of synthesized biologically active substances. The best substrates for growing mycelium of the Pleurotus ostreatus IMV 1300 strain were the waste materials produced in the distillation of clary sage and peppermint. However, in all the studied strains, the intensity of bioconversion of raw mint after sequential distillation and extraction was the most pronounced.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S. and A.V.K.; methodology, E.E.K.; software, V.N.; validation, E.S., I.T. and T.M.; formal analysis, V.D.R.; investigation, E.K.; resources, V.P.; data curation, writing—original draft preparation E.S. and V.P.; writing—review and editing, A.V.K. and V.D.R.; visualization, N.M.; supervision, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (No. FENW-2023-0008).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (No. FENW-2023-0008).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mashanov, A.I.; Velichko, N.A.; Tashlykova, E.E. Bioconversion of Plant Raw Materials; Krasnoyarsk State Agrarian University: Krasnoyarsk, Russia, 2014; p. 223. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Money, N.P. Fungi and Biotechnology. In The Fungi, 3rd ed.; Watkinson, S.C., Boddy, L., Money, N.P., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Chapter 12; pp. 401–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Vuelvas, O.F.; Cervantes-Chávez, J.A.; Delgado-Virgen, F.J.; Valdez-Velázquez, L.L.; Osuna-Cisneros, R.J. Fungal bioprocessing of lignocellulosic materials for biorefinery. In Recent Advancement in Microbial Biotechnology: Agricultural and Industrial Approach; Chapter 7; Mandal, S.D., Passari, A.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 171–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.T.; Miles, P.G. Agaricus blazei and Grifola frondosa—Two important medicinal mushrooms. In Mushrooms: Cultivation, Nutritional Value, Medicinal Effect, and Environmental Impact, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, J.; Dequin, S.; Giraud, T.; Le Tacon, F.; Marsit, S.; Ropars, J.; Richard, F.; Selosse, M. Fungi as a Source of Food. In The Fungal Kingdom; Heitman, J., Howlett, B.J., Crous, P.W., Stukenbrock, E.H., James, T.Y., Gow, N.A.R., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1063–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, D.; Wösten, H.A.B. Mushroom cultivation in the circular economy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7795–7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Statistics Database: Rome, Italy, 2022; Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#dat (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Royse, D.J.; Baars, J.; Tan, Q. Current overview of mushroom production in the world. In Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms: Technology and Applications; Zied, D.C., Pardo-Giménez, A., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Summuna, B.; Gupta, M.; Annepu, S.K. Edible Mushrooms: Cultivation, Bioactive Molecules, and Health Benefits. In Bioactive Molecules in Food; Reference Series in Phytochemistry; Mérillon, J.M., Ramawat, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishurov, N.P.; Selivanov, V.G.; Devochkina, N.L.; Rubtsov, A.A. High-tech production of edible mushrooms on an industrial basis in the Russian Federation. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 723, 032080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, C.P.; Savoie, J.M. Selected wild strains of Agaricus bisporus produce high yields of mushrooms at 25 °C. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2015, 32, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoie, J.-M.; Mata, G. Growing Agaricus bisporus as a Contribution to Sustainable Agricultural Development. In Mushroom Biotechnology: Developments and Applications; Chapter 5; Petre, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, G.; Medel, R.; Callac, P.; Billette, C.; Garibay-Orijel, R. Primer registro de Agaricus bisporus (Basidiomycota, Agaricaceae) silvestre en Tlaxcala y Veracruz, México. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2016, 87, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werghemmi, W.; Abou Fayssal, S.; Mazouz, H.; Hajjaj, H.; Hajji, L. Olive and green tea leaves extract in Pleurotus ostreatus var. florida culture media: Effect on mycelial linear growth rate, diameter and growth induction index. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1090, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbagory, M.; El-Nahrawy, S.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Eid, E.M.; Bachheti, A.; Kumar, P.; Abou Fayssal, S.; Adelodun, B.; Bachheti, R.K.; Mioč, B.; et al. Sustainable Bioconversion of Wetland Plant Biomass for Pleurotus ostreatus var. florida Cultivation: Studies on Proximate and Biochemical Characterization. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Xu, J.; Rapior, S.; Jeewon, R.; Lumyong, S.; Niego, A.G.; Abeywickrama, P.D.; Aluthmuhandiram, J.V.; Brahamanage, R.S.; Brooks, S.; et al. The Amazing Potential of Fungi: 50 Ways We can Exploit Fungi Industrially. Fungal Divers. 2019, 97, 1–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mattos-Shipley, K.; Ford KAlberti, F.; Banks, A.; Bailey, A.; Foster, G. The Good, the Bad and the Tasty: The Many Roles of Mushrooms. Stud. Mycol. 2016, 85, 125–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, E.F.; Presnyakova, E.V.; Shpichka, A.I.; Presnyakova, V.S. Eremothecium Oil Biotechnology as a Novel Technology for the Modern Essential Oil Production. In Essential Oil Research; Chapter 15; Malik, S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 401–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashtetsky, V.S.; Nevkrytaya, N.V.; Mishnev, A.V.; Nazarenko, L.G. The Essential oil Industry of Crimea. Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow; IT “Arial”: Simferopol, Russia, 2017; 244p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Pashtetsky, V.S. (Ed.) Scientific and Innovative Potential for the Development of Production and Processing of Essential and Medicinal Plants of the Eurasian Economic Union; IT “Arial”: Simferopol, Russia, 2021; 428p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Salmones, D.; Gaitan-Hernandez, R.; Mata, G. Cultivation of Mexican wild strains of Agaricus bisporus, the button mushroom, under different growth conditions in vitro and determination of their productivity. BASE 2018, 22, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, F. Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus mushrooms on Coffea arabica and Ficus sycomorus leaves in Dilla University, Ethiopia. J. Yeast Fungal Res. 2013, 4, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Amuneke, E.H.; Dike, K.S.; Ogbulie, J.N. Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus: An edible mushroom from agro base waste products. J. Microbiol. Biotech. Res. 2011, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, M.F.M.; Salem, K.F.M.; Hanna, E.T.; Nouh, N.E. Effect of Nutrient Sources and Environmental Factors on the Biomass Production of Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). J. Chem. Biol. Phy. Sci. 2014, 4, 3413–3420. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda-Insuasti, J.A.; Ramos-Sánchez, L.B.; Soto-Arroyave, C.P.; Freitas-Fragata, A.; Pereira-Cruz, L. Growth of Pleurotus ostreatus on non-supplemented agro-industrial wastes. Rev. Téc. Ing. Univ. Zulia. 2015, 38, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pashetsky, V.S.; Timasheva, L.A.; Pekhova, O.A.; Danilova, I.L.; Serebryakova, O.A. Essential Oils and Their Quality; IT “Arial”: Simferopol, Russia, 2021; 212p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- European Pharmacopoeia, 10th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2019–2022; Volume I–III, pp. 10.1–10.8.

- Shapovalova, E.N.; Pirogov, A.V. Chromatographic Methods of Analysis; Moscow State University: Moscow, Russia, 2010; 109p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- ISO 6497:2002; Animal Feeding Stuffs. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Starr, C.; McMillan, B. Atoms and Elements. In Human Biology, 11th ed.; Cengage Learning EMEA: London, UK, 2015; p. 16. 608p. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 734-1:2006; Oilseed Meals—Determination of Oil Content—Part 1: Extraction Method 1 with Hexane (or Light Petroleum). International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 5983-1:2005; Animal Feeding Stuffs—Determination of Nitrogen Content and Calculation of Crude Protein Content—Part 1: Kjeldahl Method. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- ISO 6491:1998; Animal Feeding Stuffs—Determination of Phosphorus Content—Spectrometric Method. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- ISO 6869:2000; Animal Feeding Stuffs—Determination of the Contents of Calcium, Copper, Iron, Magnesium, Manganese, Potassium, Sodium, and Zinc—Method Using Atomic Absorption Spectrometry. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- State Pharmacopoeia of the Russian Federation, 14th ed.; Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation: Moscow, Russia, 2018; Volume 4, pp. 6284–6292. (In Russian)

- Methods for Measuring the Mass Fraction of Amino Acids by Capillary Electrophoresis Using the “Kapel” Capillary Electrophoresis System; Lumeks: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2014; p. 49. (In Russian)

- Thorp, J.M.; Bowes, R.E. Carbon sources in riverine food webs: New evidence from aminoacid isotope techniques. Ecosystems 2016, 20, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulyanovsky, N.V.; Kosyakov, D.S.; Bogolitsyn, K.G. Development of express methods of analytical extraction of carotenoids from vegetable raw materials. Chem. Plant Raw Mater. 2012, 4, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Karnjanawipagul, P.; Nittayanuntawech, W.; Rojsanga, P.; Suntornsuk, L. Analysis of carotene in carrot by spectrophotometry. Mahidol Univ. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 37, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rahiman, R.; Mohd Ali, M.A.; Ab-Rahman, M.S. Carotenoids concentration detection investigation: A review of current status and future trend. Int. J. Biosci. Biochem. Bioinform. 2013, 3, 446–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, E.F.; Shpichka, A.I.; Moiseeva, I.Y. About essential oils biotechnology on the base of microbial synthesis. Eur. J. Nat. Hist. 2012, 4, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Food and Health in Europe: A New Basis for Action; Robertson, A., Ed.; WHO Regional Publications; European Series; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; Volume 96, 525p, Available online: https://www.euro.who.int (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Uddin, P.K.; O’Sullivan, J.; Pervin, R.; Rahman, M. Antioxidant of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm. and lymphoid cancer cells. In Cancer (Second Edition): Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants; Chapter 38; Academic Press: Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradies, G.; Paradies, V.; Ruggiero, F.M.; Petrosillo, G. Oxidative stress, cardiolipin and mitochondrial dysfunction in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 14205–14218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubev, V.S.; Berkovich, M.I. Healthyfood: Perception, Dynamics, Popularization. Theor. Econ. 2020, 3, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hoa, H.T.; Wang, C.L.; Wang, C.H. The effects of different substrates on the growth, yield, and nutritional composition of two oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus cystidiosus). Mycobiology 2015, 43, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, J.; Hajdú, C.S.; Gyorfi, J.; Maszlavér, P. Mineral composition of the cultivated mushrooms Agaricus bisporus, Pleurotus ostreatus and Lentinula edodes. Acta Aliment. 2005, 34, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedousi, M.; Melanouri, E.M.; Diamantopoulou, P. Carposome productivity of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus eryngii growing on agro-industrial residues enriched with nitrogen, calcium salts and oils. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2023, 6, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülser, C.; Pekşen, A. Using tea waste as a new casing material in mushroom (Agaricus bisporus (L.) Sing.) cultivation. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 88, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervakis, G.I.; Koutrotsios, G.; Katsaris, P. Composted versus raw olive mill waste as substrates for the production of medicinal mushrooms: An assessment of selected cultivation and quality parameters. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 546830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).