Estimation of Genetic Diversity between and within Biparental Clones and Full-Sib Families of the Chinese Pine Using SSR Markers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Sampling for DNA Extraction

2.2. DNA Extraction and SSR Genotyping

2.3. Genetic Statistical Analyses for Clonal Populations and Full-Sib Families

3. Results

3.1. Polymorphisms of the Selected SSR Markers

3.2. Genetic Diversity

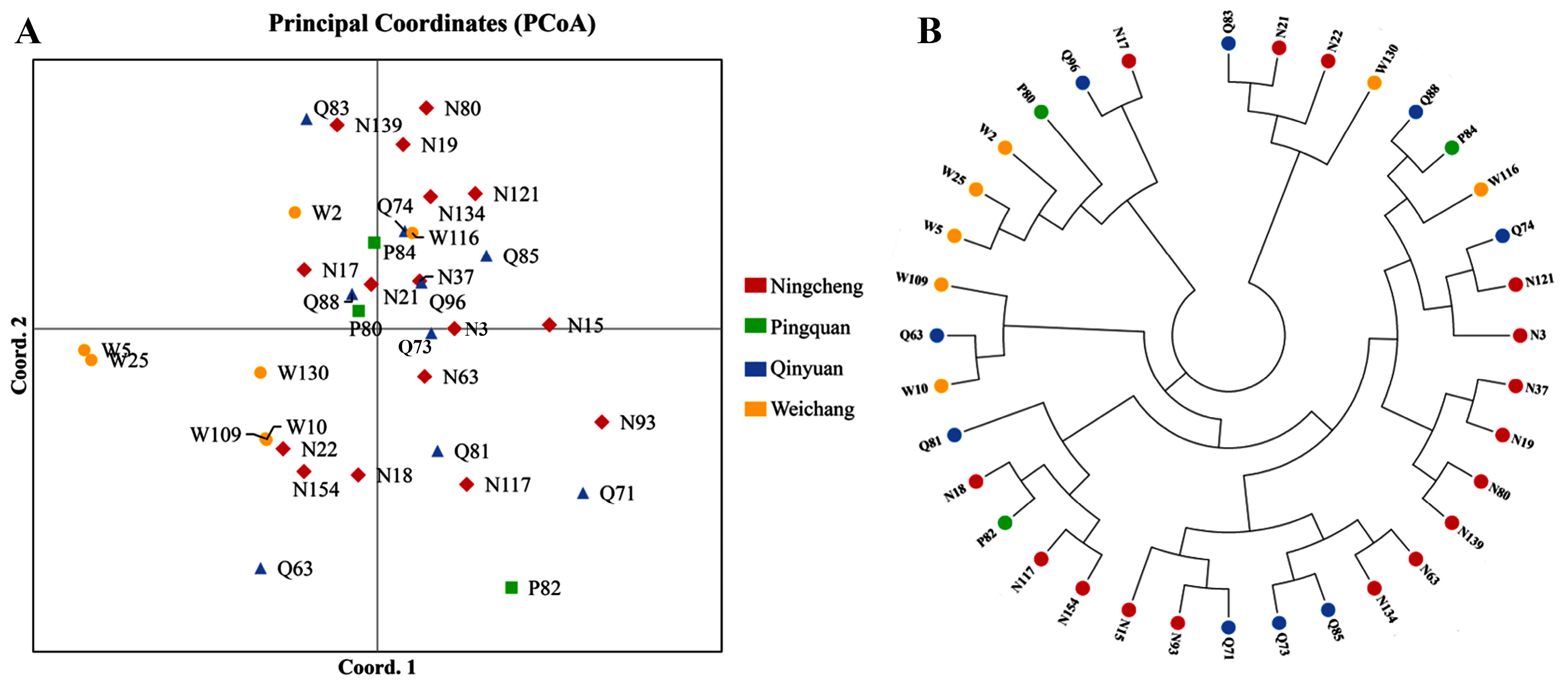

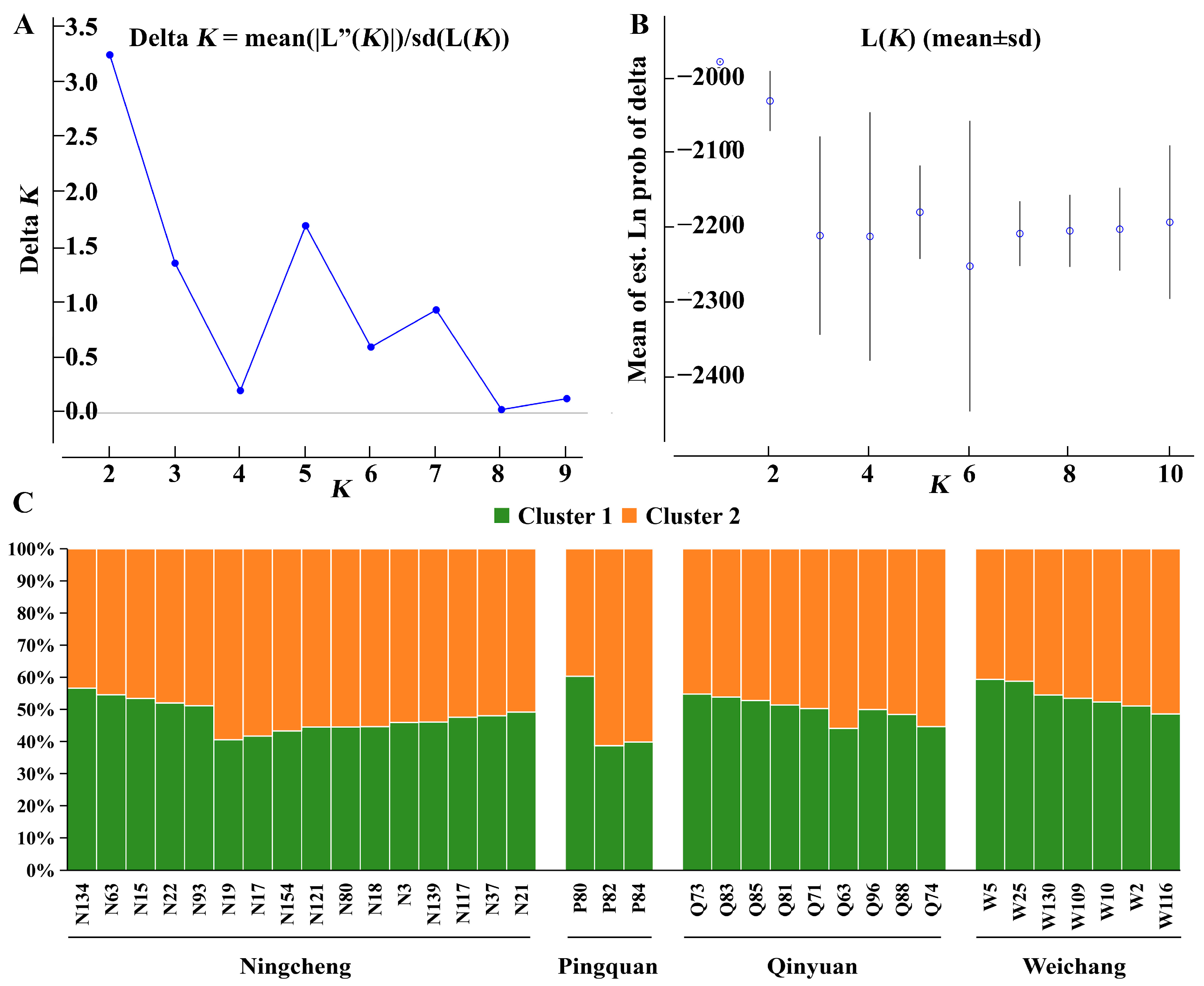

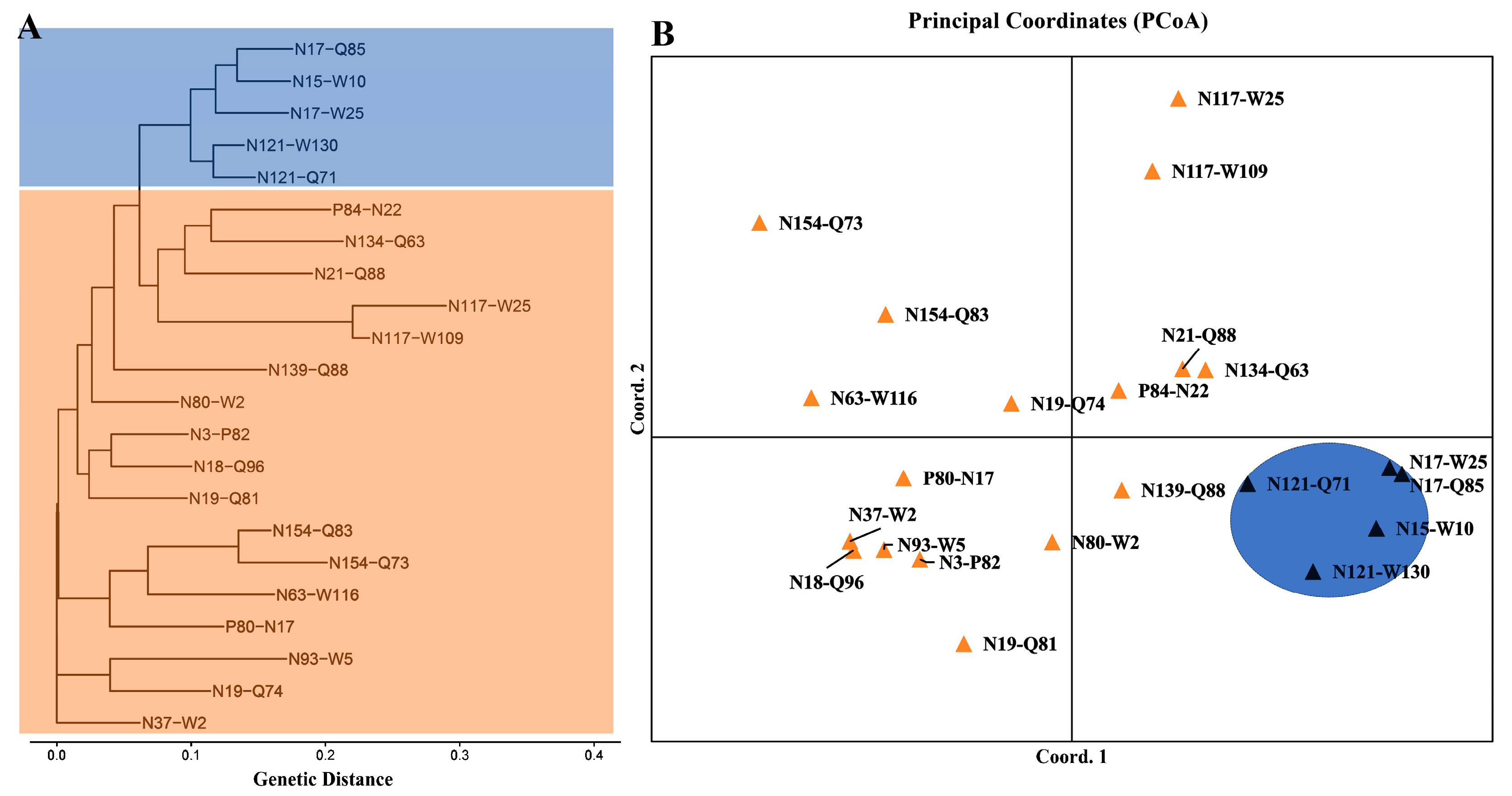

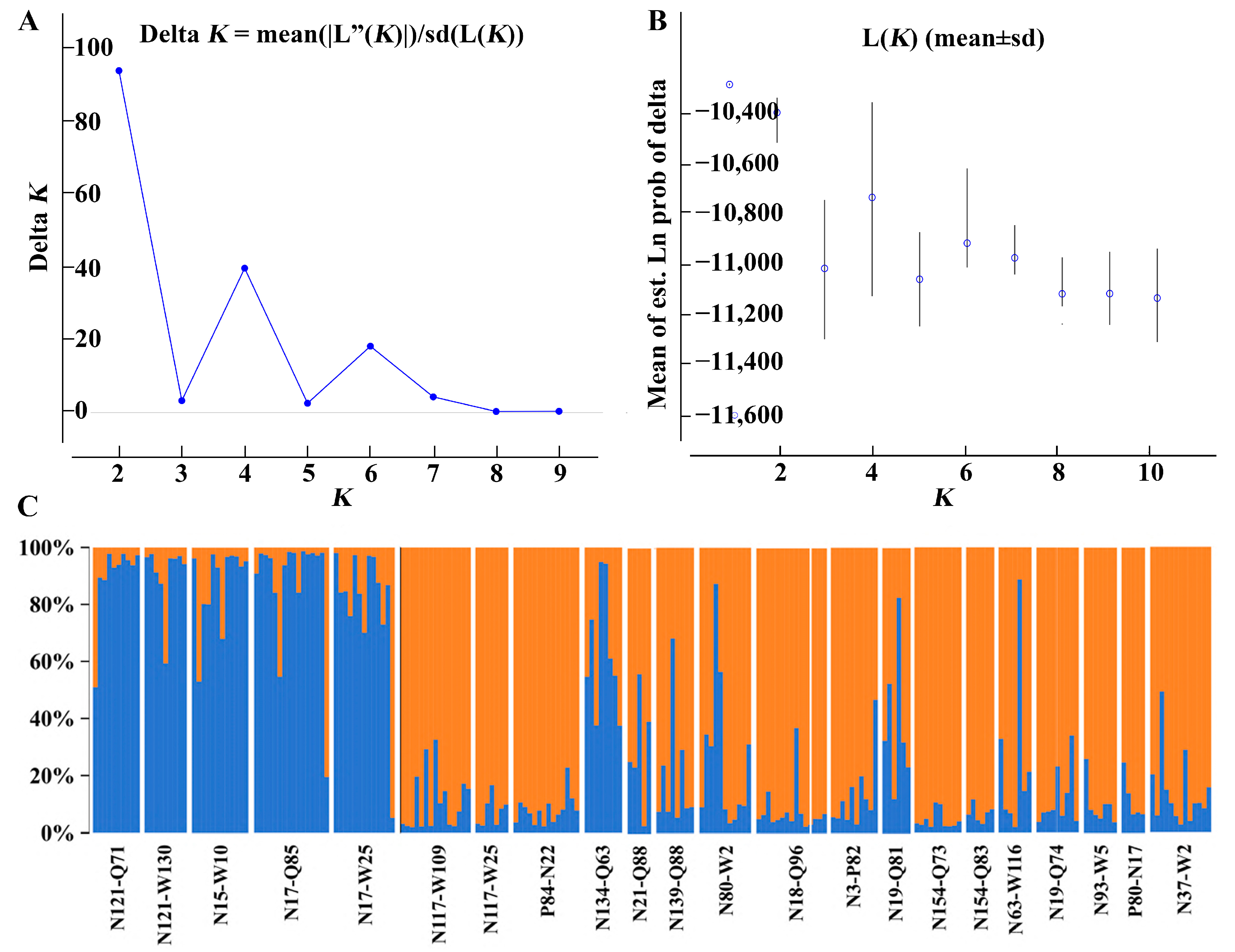

3.3. Genetic Differentiation and Structure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, W.L. Genetic diversity and genetic vulnerability—An appraisal. Econ. Bot. 1983, 37, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallauer, A.L.; Carena, M.J. Recurrent selection methods to improve germplasm in maize. Maydica 2012, 57, 266–283. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, V.R.; Hodgkin, T. Genetic diversity and conservation and utilization of plant genetic resources. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2002, 68, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Yu, D.; Dong, M.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Genetic diversity of control-pollinated progenies in seed orchard of Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii Mayr. Acta Bot. Boreali-Occid. Sin. 2016, 36, 1662–1670. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, A.B.; Gomes, W.S.; Nietsche, S.; Pereira, M.C.T.; Rodrigues, B.R.A.; Ferreira, L.B.; Paixão, P.T.M. Genetic diversity between and within full-sib families of Jatropha using ISSR markers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 124, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shen, B.; Gong, H. Genetic diversity of Simao pine in China revealed by SRAP markers. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Wen, X.; Fan, F.; Yang, Z.; Xie, W.; Hong, Y. Genetic diversity and population structure of masson pine (Pinus massoniana Lamb.) superior clones in South China as revealed by EST-SSR markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2021, 68, 1987–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, H.; Setoguchi, H. A multilocus sequencing approach reveals the cryptic phylogeographical history of Phyllodoce nipponica Makino (Ericaceae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2013, 110, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, M.; Xie, D.; Xie, C.; Deng, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yu, Y.; He, X. A Phytogeographic Divide Along the 500 mm Isohyet in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: Insights From the Phylogeographic Evidence of Chinese Alliums (Amaryllidaceae). Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Li, C.; Zhou, C.; Chen, J.; Li, F.; Weng, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; et al. Genetic diversity analysis of a breeding population of Eucalyptus cloeziana F. Muell. (Myrtaceae) and extraction of a core germplasm collection using microsatellite markers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 145, 112157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.A.; da Silva, H.D.; Lavoranti, O.J. Dendroenergetical characterization of Eucalyptus benthamii trees. Pesq. Florest. Bras. 2011, 31, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, J.; Pan, Y.; Hu, X.; Nan, X.; Liu, D.; Li, Y. Variation analyses of controlled pollinated families and parental combining ability of Pinus koraiensis. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, G.R.; Volker, P.W.; Potts, B.M.; Owen, J.V. A comparison of genetic information from open-pollinated and control-pollinated progeny tests in two eucalypt species. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1996, 92, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Sastry, E.V.D.; Singhania, D.L. Comparison of full sib, half sib and S1 progenies in fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.). J. Spices Aromat. Crops 2004, 13, 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- Brauner, P.C.; Müller, D.; Molenaar, W.S.; Melchinger, A.E. Genomic prediction with multiple biparental families. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grattapaglia, D.; Silva-Junior, O.B.; Resende, R.T.; Cappa, E.P.; Müller, B.S.F.; Tan, B.; Isik, F.; Ratcliffe, B.; El-Kassaby, Y.A. Quantitative Genetics and Genomics Converge to Accelerate Forest Tree Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, R.T.; Resende, M.D.V.; Silva, F.F.; Azevedo, C.F.; Takahashi, E.K.; Silva-Junior, O.B.; Grattapaglia, D. Assessing the expected response to genomic selection of individuals and families in Eucalyptus breeding with an additive-dominant model. Heredity 2017, 119, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awata, L.A.O.; Tongoona, P.; Danquah, E.; Efie, B.E.; Marchelo-Dragga, P.W. Common mating designs in agricultural research and their reliability in estimation of genetic parameters. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2018, 11, 16–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vencovsky, R.; Ramalho, M.A.P.; Toledo, F.H.R.B. Contribution and perspectives of quantitative genetics to plant breeding in Brazil. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 2012, 12, 07–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zietkiewicz, E.; Rafalski, A.; Labuda, D. Genome fingerprinting by simple sequence repeat (SSR)-anchored polymerase chain reaction amplification. Genomics 1994, 20, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Mu, K.; Ni, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.-A. Analysis of genetic diversity of ancient Ginkgo populations using SSR markers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 145, 111942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, H.; Hamidoghli, Y.; Samizadeh, H. Estimation of genetic diversity in some Iranian cornelian cherries (Cornus mas L.) accessions using ISSR markers. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2013, 48, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Castro, I.; Rocha, J.; Crespí, A.L.; Pinto-Carnide, O.; Amich, F.; Almeida, R.; Carnide, V. Chloroplast and nuclear DNA studies in Iberian Peninsula endemic Silene scabriflora subspecies using cpSSR and ISSR markers: Genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2015, 61, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellicka, R.; Rossettoa, M.; Allena, C.; Wilsond, P.D.; Hillc, R.S.; Loweb, A. Intraspecific Divergence Associated with a Biogeographic Barrier and Climatic Models Show Future Threats and Long-Term Decline of a Rainforest Conifer. Open Conserv. Biol. J. 2013, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Gao, C.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Cui, K. Genetic diversity, population structure and a core collection establishment of Pinus yunnanensis using microsatellite markers. Eur. J. For. Res. 2023, 142, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Niu, S.; Li, Y. Genetic diversity, genetic structure, and germplasm source of Chinese pine in North China. Eur. J. For. Res. 2023, 142, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, B.A.; Klopfenstein, N.B.; Brunsfeld, S.J. Assessing clark’s nutcracker seed-caching flights using maternally inherited mitochondrial DNAof whitebark pine. Can. J. Res. 2002, 32, 1103–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burban, C.; Petit, R.J. Phylogeography of maritime pine inferred with organelle markers having contrasted inheritance. Mol. Ecol. 2003, 12, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepelt, S.; Bialozyt, R.; Ziegenhagen, B. Wind-dispersed pollen mediates postglacial gene flow among refugia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, M.; Yoshimaru, H.; Saito, H.; Katsuki, T.; Kawahara, T.; Kitamura, K.; Shi, F.; Kaji, M. Phylogeography of a northeast Asian spruce, Picea jezoensis, inferred from genetic variation observed in organelle DNA markers. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 3393–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, H.; Meikar, T. Exotic coniferous trees in Estonian forestry after 1918. Allg. Forst Jagdztg. 2009, 180, 158–169. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, W.T.; Gernandt, D.S.; Wehenkel, C.; Xia, X.M.; Wei, X.X.; Wang, X.Q. Phylogenomic and ecological analyses reveal the spatiotemporal evolution of global pines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2022302118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Li, N.; Elias, T.S.; Mill, R.R. Pinaceae Lindley. In Flora of China; Raven, P., Wu, Z., Hong, D., Eds.; Science Press: Beijing, China; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, MI, USA, 1999; Volume 4, pp. 11–52. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S.; Li, J.; Bo, W.; Yang, W.; Zuccolo, A.; Giacomello, S.; Chen, X.; Han, F.; Yang, J.; Song, Y.; et al. The Chinese pine genome and methylome unveil key features of conifer evolution. Cell 2022, 185, 204–217.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yun, Y.; Zhang, G. Transcriptome Analysis and Novel EST-SSR Marker Development for Pinus tabuliformis Seedlings from Four Provenances. Forests 2023, 14, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Dang, L.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, X.; Jia, H.; Zhang, H. Genetic diversity analysis of Pinus tabulaeformis seed orchard based on EST-SSR marker. J. Hebei Agric. Univ. 2021, 44, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Smouse, P.E.; Banks, S.C.; Peakall, R. Converting quadratic entropy to diversity: Both animals and alleles are diverse, but some are more diverse than others. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Muse, S.V. PowerMarker: An integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 2128–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Wen, X.Q.; Falush, D. Documentation for Structure Software, Version 2.3. Available online: http://web.stanford.edu/group/pritchardlab/structure.html (accessed on 4 October 2023).

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Yan, S.; Ren, W.; Xing, N.; Li, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, X.; Ma, W. Genetic diversity of the Chinese medicinal plant Astragali radix based on transcriptome-derived SSR markers. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 62, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Luo, J.; Yao, Z.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Shen, Y. Development of EST-SSR markers and their application in an analysis of the genetic diversity of the endangered species Magnolia sinostellata. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2019, 294, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, M.C.; Cassini, S.T.A.; Oliveira, V.R.; Tsai, S.M. Caracterização da diversidade genética em feijão por meio de marcadores RAPD. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 2001, 36, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Srivastava, M.; Mishra, G.P.; Naik, P.K.; Chauhan, R.S.; Tiwari, S.K.; Kumar, M.; Singh, R. Analogy of ISSR and RAPD markers for comparative analysis of genetic diversity among different Jatropha curcas genotypes. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 4230–4243. [Google Scholar]

- Nei, M. Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1973, 70, 3321–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Xue, X.; Hu, X.; He, Y.; Wei, S.; Liu, S.; Zhao, G.; Wang, Z.; Hou, X. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure Analysis of Tree Peony (Paeonia Section Moutan DC.) Germplasm Using Sixteen Functional SSR Markers. Forests 2023, 14, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Wu, G.L.; Dong, C.C.; Liu, J.Q.; Li, M.J. Genomic divergence and introgression among three Populus species. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2023, 180, 107686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavhan, R.L.; Sable, S.; Narwade, A.V.; Hinge, V.R.; Kalbande, B.B.; Mukherjee, A.K.; Chakrabarty, P.K.; Kadam, U.S. Multiplex molecular marker-assisted analysis of significant pathogens of cotton (Gossypium sp.). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 47, 102557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Kadam, U.S.; Chacko, P.M.; Aher, L.; Karibasappa, G.S. Microsatellite analysis to differentiate clones of Thompson Seedless grapevine. Indian J. Hortic. 2010, 67, 260–263. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay, A.; Kadam, U.S.; Chacko, P.; Karibasappa, G.S. Microsatellite and RAPD analysis of grape (Vitis spp.) accessions and identification of duplicates/misnomers in germplasm collection. Indian J. Hortic. 2010, 67, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hinge, V.R.; Shaikh, I.M.; Chavhan, R.L.; Deshmukh, A.S.; Shelake, R.M.; Ghuge, S.A.; Dethe, A.M.; Suprasanna, P.; Kadam, U.S. Assessment of genetic diversity and volatile content of commercially grown banana (Musa spp.) cultivars. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Q.; Wang, B.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, D.; Li, B. Genetic diversity and population structure of Chinese white poplar (Populus tomentosa) revealed by SSR markers. J. Hered. 2012, 103, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandák, B.; Hadincová, V.; Mahelka, V.; Wildová, R. European invasion of North American Pinus strobus at large and fine scales: High genetic diversity and fine-scale genetic clustering over time in the adventive range. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Niu, S.; El-Kassaby, Y.A.; Li, W. Monitoring genetic diversity across Pinus tabuliformis seed orchard generations using SSR markers. Can. J. For. Res. 2021, 51, 1534–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, B. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Shortleaf Pine (Pinus echinata) in the Missouri Ozarks. Am. Midl. Nat. 2018, 180, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, E.G.; Tremblay, F.; Housset, J.M.; Bergeron, Y.; Carcaillet, C. Geographic isolation and climatic variability contribute to genetic differentiation in fragmented populations of the long-lived subalpine conifer Pinus cembra L. in the western Alps. BMC Evol. Biol. 2019, 19, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.-Y.; Lee, J.-W.; Hong, K.-N. Genetic diversity and structure of Pinus densiflora Siebold & Zucc. populations in Republic of Korea based on microsatellite markers. Forests 2021, 12, 750. [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin, M. Gene flow and selection in a cline. Genetics 1973, 75, 733–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.M.; Sun, P.G.; Shen, X.H.; Ru, G.X. Paternity analysis of open- and control-pollinated seeds Collected from a seed orchard of Pinus tabulaeformis. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2009, 33, 302–310. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.M.; Abbott, R.J.; Milne, R.I.; Tian, X.M.; Liu, J.Q. Phylogeography of Pinus tabulaeformis carr. (pinaceae), a domi nant species of coniferous forest in northern china. Mol. Ecol. 2008, 17, 4276–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.H. Landscape Genomics of Pinus tabuliformis Carr. and Its Evolutionary History; Beijing Forestry University: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, C.D.; Souza Carneiro, P.C. Modelos Biométricos Aplicados ao Melhoramiento Genético. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bhering, L.L.; Peixoto, L.d.A.; Ferreira Leite, N.L.S.; Laviola, B.G. Molecular analysis reveals new strategy for data collection in order to explore variability in Jatropha. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 74, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laviola, B.G.; Alves, A.A.; Rosado, T.B.; Bhering, L.L.; Formighieri, E.F.; Peixoto, L.d.A. Establishment of new strategies to quantify and increase the variability in the Brazilian Jatropha genotypes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 117, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Orchard Name | Location | Longitude | Latitude | Number of Clones |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qigou Forest Farm National Pinus tabuliformis Seed Orchard | Pingquan city, Hebei Province | 118°40′ E | 41°22′ N | 3 |

| Heilihe Forest Farm National Pinus tabuliformis Seed Orchard | Ningcheng County, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region | 112°02′ E | 36°40′ N | 16 |

| Weichang Longtou Mountain Forest Farm | Weichang Manchu and Mongolian Autonomous County, Chengde City, Hebei Province | 117°12′ E | 42°18′ N | 7 |

| Lingkong Mountain National Nature Reserve | Qinyuan County, Shanxi Province | 118°25′ E | 41°35′ N | 9 |

| Population | ♀-♂Clones | Na | Ne | I | Ho | He |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clone populations | Ningcheng (N) | 5.238 | 3.240 | 1.289 | 0.650 | 0.662 |

| Pingquan (P) | 3.048 | 2.614 | 0.978 | 0.619 | 0.577 | |

| Qinyuan (Q) | 4.048 | 2.821 | 1.124 | 0.630 | 0.613 | |

| Weichang (W) | 3.619 | 2.504 | 1.016 | 0.646 | 0.569 | |

| Mean | 3.988 | 2.795 | 1.102 | 0.636 | 0.605 | |

| Hybrid progenies | N117-W109 | 3.857 | 2.474 | 1.031 | 0.581 | 0.572 |

| N117-W25 | 2.905 | 2.240 | 0.845 | 0.571 | 0.496 | |

| N121-Q71 | 3.238 | 2.441 | 0.973 | 0.724 | 0.572 | |

| N121-W130 | 3.286 | 2.325 | 0.939 | 0.667 | 0.543 | |

| N134-Q63 | 3.190 | 2.248 | 0.884 | 0.607 | 0.515 | |

| N139-Q88 | 3.381 | 2.478 | 0.973 | 0.625 | 0.558 | |

| N15-W10 | 3.952 | 2.434 | 1.008 | 0.651 | 0.556 | |

| N154-Q73 | 3.429 | 2.325 | 0.946 | 0.652 | 0.537 | |

| N154-Q83 | 3.476 | 2.550 | 0.995 | 0.587 | 0.552 | |

| N17-Q85 | 4.048 | 2.531 | 1.034 | 0.655 | 0.569 | |

| N17-W25 | 3.286 | 2.236 | 0.885 | 0.597 | 0.506 | |

| N18-Q96 | 3.476 | 2.185 | 0.891 | 0.622 | 0.498 | |

| N19-Q74 | 3.571 | 2.486 | 0.996 | 0.640 | 0.562 | |

| N19-Q81 | 3.095 | 2.243 | 0.888 | 0.571 | 0.517 | |

| N21-Q88 | 3.190 | 2.351 | 0.931 | 0.629 | 0.535 | |

| N3-P82 | 3.476 | 2.578 | 0.988 | 0.624 | 0.555 | |

| N37-W2 | 4.048 | 2.649 | 1.068 | 0.663 | 0.583 | |

| N63-W116 | 3.238 | 2.273 | 0.891 | 0.619 | 0.507 | |

| N80-W2 | 3.952 | 2.550 | 1.048 | 0.680 | 0.575 | |

| N93-W5 | 3.095 | 2.263 | 0.891 | 0.653 | 0.518 | |

| P80-N17 | 3.286 | 2.470 | 0.945 | 0.695 | 0.532 | |

| P84-N22 | 4.048 | 2.565 | 1.051 | 0.633 | 0.568 | |

| Mean | 3.478 | 2.404 | 0.959 | 0.634 | 0.542 |

| Samples | Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clone populations | Among populations | 3 | 27.640 | 9.213 | 0.143 | 2% |

| Within populations | 66 | 458.975 | 6.954 | 6.954 | 98% | |

| Total | 69 | 486.614 | 7.097 | 100% | ||

| Full-sib families | Among families | 21 | 441.391 | 21.019 | 0.767 | 11% |

| Within families | 410 | 2474.262 | 6.035 | 6.035 | 89% | |

| Total | 431 | 2915.653 | 6.802 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, S.; Ji, P.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yun, Y.; Zhang, G. Estimation of Genetic Diversity between and within Biparental Clones and Full-Sib Families of the Chinese Pine Using SSR Markers. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9111205

Guo S, Ji P, Wang J, He Y, Zhang Y, Zhang F, Yun Y, Zhang G. Estimation of Genetic Diversity between and within Biparental Clones and Full-Sib Families of the Chinese Pine Using SSR Markers. Horticulturae. 2023; 9(11):1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9111205

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Shuai, Penghao Ji, Ju Wang, Yujiao He, Yongxin Zhang, Feng Zhang, Yufei Yun, and Guosheng Zhang. 2023. "Estimation of Genetic Diversity between and within Biparental Clones and Full-Sib Families of the Chinese Pine Using SSR Markers" Horticulturae 9, no. 11: 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9111205

APA StyleGuo, S., Ji, P., Wang, J., He, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, F., Yun, Y., & Zhang, G. (2023). Estimation of Genetic Diversity between and within Biparental Clones and Full-Sib Families of the Chinese Pine Using SSR Markers. Horticulturae, 9(11), 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9111205