Combined Use of Spent Mushroom Substrate Biochar and PGPR Improves Growth, Yield, and Biochemical Response of Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis): A Preliminary Study on Greenhouse Cultivation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Experimental Materials

2.2. Biochar Production and Characterization

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Chemical Analyses

2.5. Growth and Biochemical Analyses

2.6. Data Analysis and Software

3. Results and Discussion

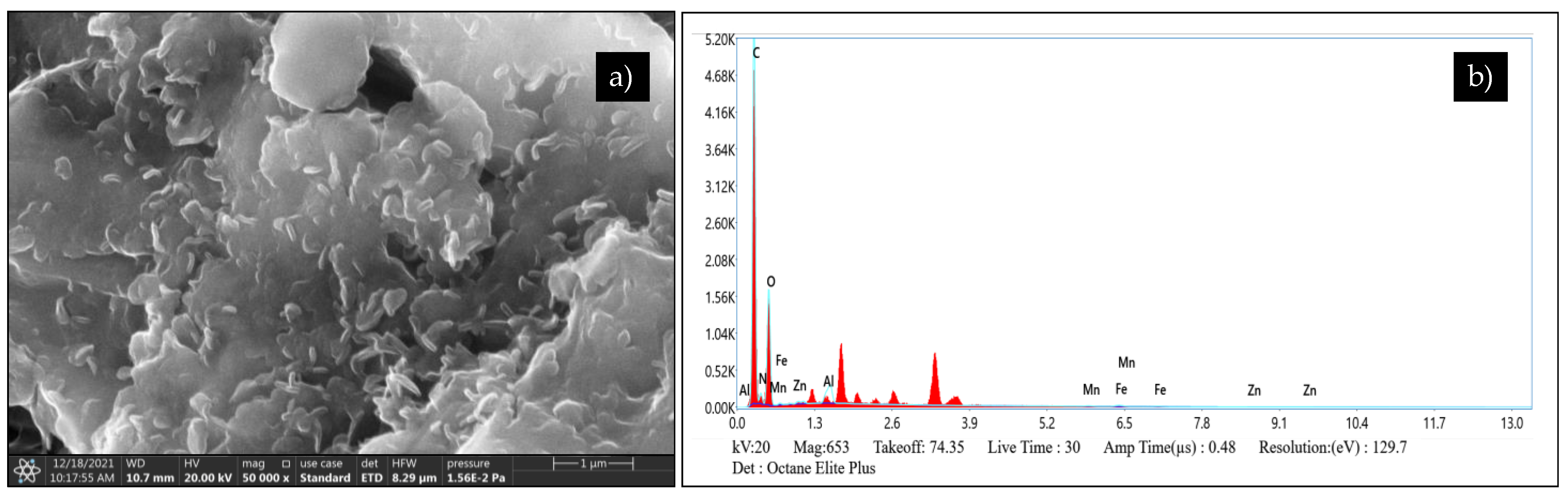

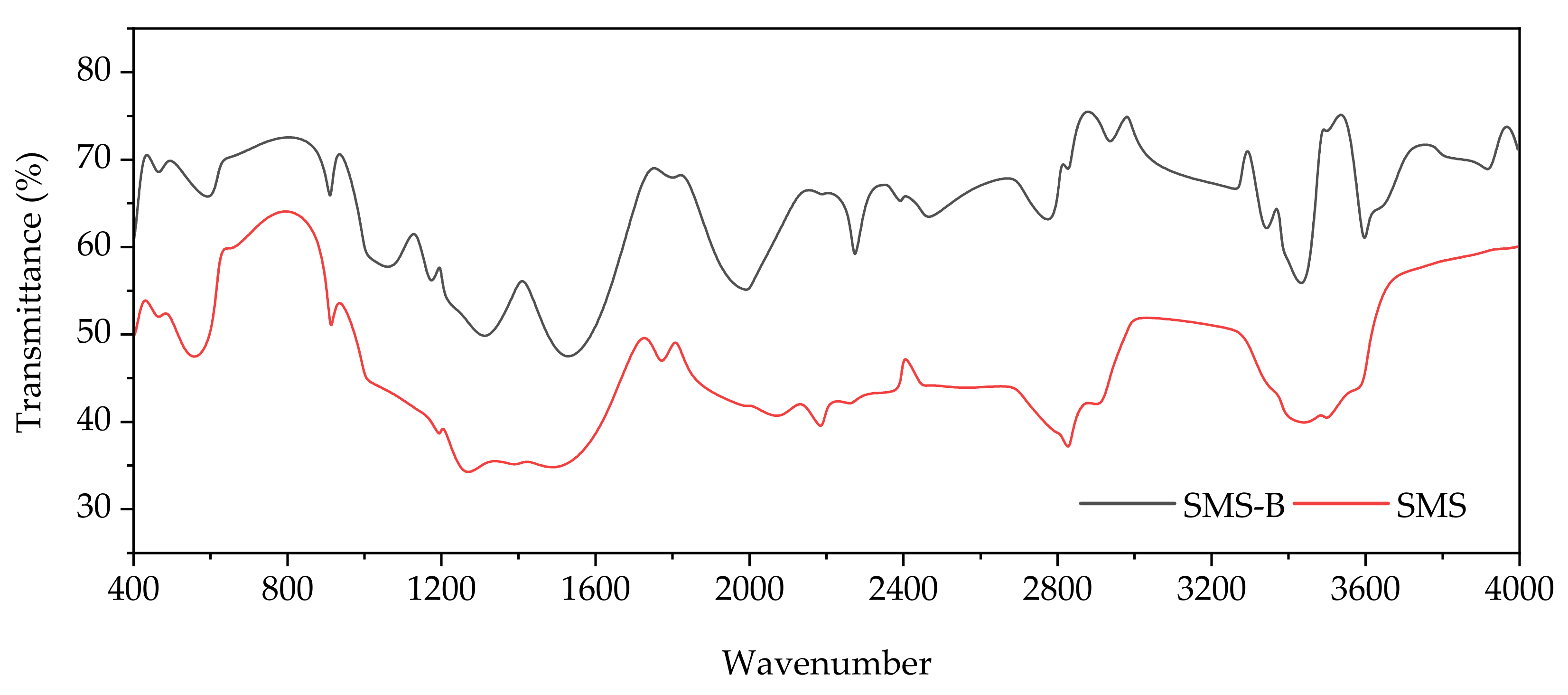

3.1. Characteristics of Spent Mushroom Substrate and Biochar

3.2. Effect of Biochar Addition on Soil Nutrients

3.3. Effect of SMS Biochar and PGPR on Growth and Yield of Cauliflower

3.4. Effect of SMS Biochar and PGPR on Biochemical Response of Cauliflower

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, F.A.; Ali, R.F.M. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Fresh and Processed White Cauliflower. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 367819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helgi Library. Which Country Produces the Most Cauliflower? Available online: https://www.helgilibrary.com/charts/which-country-produces-the-most-cauliflower/ (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Market Data Forecast. Cauliflower and Broccoli Market. Available online: https://www.marketdataforecast.com/market-reports/cauliflower-and-broccoli-market (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Abou Fayssal, S.; El Sebaaly, Z.; Alsanad, M.A.; Najjar, R.; Böhme, M.; Yordanova, M.H.; Sassine, Y.N. Combined Effect of Olive Pruning Residues and Spent Coffee Grounds on Pleurotus ostreatus Production, Composition, and Nutritional Value. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Eid, E.M.; Taher, M.A.; El-Morsy, M.H.E.; Osman, H.E.M.; Al-Bakre, D.A.; Adelodun, B.; Abou Fayssal, S.; Goala, M.; Mioč, B.; et al. Biotransforming the Spent Substrate of Shiitake Mushroom (Lentinula edodes Berk.): A Synergistic Approach to Biogas Production and Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Fertilization. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlashan, N.; Shah, N.; Caldecott, B.; Workman, M. High-level techno-economic assessment of negative emissions technologies. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2012, 90, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Goal 13: Take Urgent Action to Combat Climate Change and Its Impacts. Climate Action. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-change/ (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Çığ, F.; Sönmez, F.; Nadeem, M.A.; Sabagh, A. El Effect of Biochar and PGPR on the Growth and Nutrients Content of Einkorn Wheat (Triticum monococcum L.) and Post-Harvest Soil Properties. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, M.I.; Gao, B.; Yao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zimmerman, A.; Mosa, A.; Cao, X. A review of biochar as a low-cost adsorbent for aqueous heavy metal removal. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 46, 406–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Rillig, M.C.; Thies, J.; Masiello, C.A.; Hockaday, W.C.; Crowley, D. Biochar Effects on Soil Biota—A Review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1812–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pii, Y.; Mimmo, T.; Tomasi, N.; Terzano, R.; Cesco, S.; Crecchio, C. Microbial Interactions in the Rhizosphere: Beneficial Influences of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria on Nutrient Acquisition Process. A Review. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2015, 51, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, R.; Rokem, J.S.; Ilangumaran, G.; Lamont, J.; Praslickova, D.; Ricci, E.; Subramanian, S.; Smith, D.L. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria: Context, Mechanisms of Action, and Roadmap to Commercialization of Biostimulants for Sustainable Agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 871, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, V.; Viswanathan, R.; Raguchander, T.; Prakasam, V.; Samiyappan, R. Induction of Systemic Resistance by Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria in Crop Plants against Pests and Diseases. Crop Prot. 2001, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.; Sun, Y.; Bian, S.; Ali Baig, S.; Hu, B.; Xu, X. Nutrient Conservation during Spent Mushroom Compost Application Using Spent Mushroom Substrate Derived Biochar. Chemosphere 2017, 169, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.L.; Chen, X.M.; Sun, J.; Liu, J.Y.; Sun, S.Y.; Yang, Z.Y.; Wang, Y. Spent Mushroom Substrate Biochar as a Potential Amendment in Pig Manure and Rice Straw Composting Processes. Environ. Technol. 2017, 38, 1765–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.S.; Tsai, W.T.; Lin, Y.Q.; Tsai, C.H.; Chang, Y.T. Production of Highly Porous Biochar Materials from Spent Mushroom Composts. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, K.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M.; Chauhan, D.K.; Tripathi, D.K.; Sharma, S. Silicon and Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Differentially Regulate AgNP-Induced Toxicity in Brassica juncea: Implication of Nitric Oxide. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 390, 121806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artyszak, A.; Gozdowski, D. Application of Growth Activators and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria as a Method of Introducing a “Farm to Fork” Strategy in Crop Management of winter Oilseed. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, J.; Kumar, P. Studies on Conjoint Application of Nutrient Sources and PGPR on Growth, Yield, Quality, and Economics of Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis L.). J. Plant Nutr. 2018, 41, 1862–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella Mary, G.; Sugumaran, P.; Niveditha, S.; Ramalakshmi, B.; Ravichandran, P.; Seshadri, S. Production, Characterization and Evaluation of Biochar from Pod (Pisum sativum), Leaf (Brassica oleracea) and Peel (Citrus sinensis) Wastes. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2016, 5, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, J.; McGrouther, K.; Huang, H.; Lu, K.; Guo, X.; He, L.; Lin, X.; Che, L.; Ye, Z.; et al. Effect of Biochar on the Extractability of Heavy Metals (Cd, Cu, Pb, and Zn) and Enzyme Activity in Soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Chakravarthi, M.H.; Srivastava, V.C. Chemically Modified Biochar Derived from Effluent Treatment Plant Sludge of a Distillery for the Removal of an Emerging Pollutant, Tetracycline, from Aqueous Solution. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2021, 11, 2735–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association (APHA): Washington, DC, USA, 1999; Volume 51. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. AOAC Official Methods of Analysis, 21st ed.; AOAC International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An Examination of the Degtjareff Method for Determining Soil Organic Matter and a Proposed Modification of the Chromic Acid Titration Method. Soil Sci. 1933, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chromý, V.; Vinklárková, B.; Šprongl, L.; Bittová, M. The Kjeldahl Method as a Primary Reference Procedure for Total Protein in Certified Reference Materials Used in Clinical Chemistry. I. A Review of Kjeldahl Methods Adopted by Laboratory Medicine. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2015, 45, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Thakur, R.K.; Kumar, P. Assessment of Heavy Metals Uptake by Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis) Grown in Integrated Industrial Effluent Irrigated Soils: A Prediction Modeling Study. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 257, 108682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, L.C.R.; de Oliveira, V.R.; Hagen, M.E.K.; Jablonski, A.; Flôres, S.H.; de Oliveira Rios, A. Carotenoids, Flavonoids, Chlorophylls, Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Fresh and Cooked Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. avenger) and Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. alphina F1). LWT 2015, 63, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, M.; Akram, N.A.; Ashraf, M.; Tyagi, A.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Ahmad, P. Thiamin Stimulates Growth, Yield Quality and Key Biochemical Processes of Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L. var. botrytis) under Arid Conditions. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper Enzymes in Isolated Chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, R.; Prakash, N.B. Effect of Different Biochars on Acid Soil and Growth Parameters of Rice Plants under Aluminium Toxicity. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabhi, R.S.; Kirk, D.W.; Jia, C.Q. Preliminary Investigation of Electrical Conductivity of Monolithic Biochar. Carbon 2017, 116, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, V.; Adelodun, B.; Bedeković, D.; Kos, I.; Širić, I.; Alamri, S.A.M.; Alrumman, S.A.; Eid, E.M.; Abou Fayssal, S.; et al. Sustainable Use of Sewage Sludge as a Casing Material for Button Mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) Cultivation: Experimental and Prediction Modeling Studies for Uptake of Metal Elements. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Eid, E.M.; Al-Huqail, A.A.; Širić, I.; Adelodun, B.; Fayssal, S.A.; Valadez-Blanco, R.; Goala, M.; Ajibade, F.O.; Choi, K.S.; et al. Kinetic Studies on Delignification and Heavy Metals Uptake by Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) Mushroom Cultivated on Agro-Industrial Wastes. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, R.A.L.; Pickler, T.B.; Segato, T.C.M.; Jozala, A.F.; Grotto, D. Biochar from Fungiculture Waste for Adsorption of Endocrine Disruptors in Water. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, M.; Clothier, B.; Bound, S.; Oliver, G.; Close, D. Does Biochar Influence Soil Physical Properties and Soil Water Availability? Plant Soil 2014, 376, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; McNamara, P.J.; Mayer, B.K. Adsorption of Organic Micropollutants onto Biochar: A Review of Relevant Kinetics, Mechanisms and Equilibrium. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2019, 5, 821–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Rehman, I.U. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy of Biological Tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2008, 43, 134–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, R.; Ambrosini, R.; Montagnani, C.; Caronni, S.; Citterio, S. Effect of Soil Ph on the Growth, Reproductive Investment and Pollen Allergenicity of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.K.L.; Yeom, M.S.; Oh, M.M. Effect of a Newly-Developed Nutrient Solution and Electrical Conductivity on Growth and Bioactive Compounds in Perilla frutescens var. crispa. Agronomy 2021, 11, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, X.; Song, N. Biochar and vermicompost improve the soil properties and the yield and quality of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) grown in plastic shed soil continuously cropped for different years. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 315, 107425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, P.; Khan, A. Optimization of PGPR and Silicon Fertilization Using Response Surface Methodology for Enhanced Growth, Yield and Biochemical Parameters of French Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under Saline Stress. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 23, 101463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Wu, Z.; He, X.; Ye, B.C.; Li, C. Characterization of Biochar Prepared from Cotton Stalks as Efficient Inoculum Carriers for Bacillus subtilis SL-13. BioResources 2018, 13, 1773–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripti; Kumar, A.; Usmani, Z.; Kumar, V. Anshumali Biochar and Flyash Inoculated with Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Act as Potential Biofertilizer for Luxuriant Growth and Yield of Tomato Plant. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 190, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, S.M.; Imran, M.; Naveed, M.; Khan, M.Y.; Ahmad, M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Crowley, D.E. Synergistic Use of Biochar, Compost and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria for Enhancing Cucumber Growth under Water Deficit Conditions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 5139–5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, N.; Ditta, A.; Khalid, A.; Mehmood, S.; Rizwan, M.S.; Ashraf, M.; Mubeen, F.; Imtiaz, M.; Iqbal, M.M. Integrated Effect of Algal Biochar and Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria on Physiology and Growth of Maize Under Deficit Irrigations. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangir, S.; Javed, K.; Bano, A. Nanoparticles and Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) Modulate the Physiology of Onion Plant under Salt Stress. Pak. J. Bot. 2020, 52, 1473–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighodaro, O.M.; Akinloye, O.A. First Line Defence Antioxidants-Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Catalase (CAT) and Glutathione Peroxidase (GPX): Their Fundamental Role in the Entire Antioxidant Defence Grid. Alex. J. Med. 2018, 54, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanpour, M.; Hatami, M.; Khavazi, K. Role of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria on Antioxidant Enzyme Activities and Tropane Alkaloid Production of Hyoscyamus niger under Water Deficit Stress. Turk. J. Biol. 2013, 37, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalay, G.; Ullah, S.; Ahmed, I. Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Brassica napus L. to Drought-Induced Stress by the Application of Biochar and Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2022, 85, 1267–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Farooq Qayyum, M.; Abbas, F.; Hannan, F.; Rinklebe, J.; Sik Ok, Y. Effect of Biochar on Cadmium Bioavailability and Uptake in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Grown in a Soil with Aged Contamination. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 140, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.; Moghadam, A.L.; Hakimi, L.; Danaee, E. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) Improve Plant Growth, Antioxidant Capacity, and Essential Oil Properties of Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) under Water Stress. Iran. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 10, 3155–3166. [Google Scholar]

| Properties | Spent Mushroom Substrate (SMS) | Biochar @ 600 °C (10 °C/min for 1 h) |

|---|---|---|

| pH (H2O) | 5.02 ± 0.02 | 8.10 ± 0.01 |

| Electrical Conductivity (EC: dS/m) | 4.83 ± 0.20 | 2.09 ± 0.02 |

| Moisture Content (MC: %) | 56.66 ± 3.70 | 0.40 ± 0.03 |

| Organic Carbon (OC: %) | 23.40 ± 1.53 | Na |

| Total Nitrogen (N: %) | 0.92 ± 0.06 | 7.15 ± 0.02 |

| C:N ratio | 25.43 ± 0.10 | 8.67 ± 0.02 |

| Total Phosphorus (P: %) | 0.21 ± 0.02 | Na |

| Total Potassium (K: %) | 0.70 ± 0.04 | Na |

| Biochar Yield (%) | Na | 19.80 ± 0.15 |

| Pore Size (nm) | Na | 0.92 ± 0.20 |

| BET Surface Area (m2/g) | Na | 5.10 ± 0.08 |

| Carbon (C: %) | Na | 62.06 ± 0.52 |

| Oxygen (O: %) | Na | 25.23 ± 0.18 |

| Manganese (Mn: %) | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.01 |

| Iron (Fe: %) | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 0.35 ± 0.01 |

| Zinc (Zn: %) | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.01 |

| Soil Properties | Treatments | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control-T1 | T2-T3 (5 g/Kg) | T4-T5 (10 g/Kg) | |

| pH | 7.20 ± 0.02 a | 7.28 ± 0.03 b | 8.01 ± 0.02 c |

| Electrical Conductivity (EC: dS/m) | 1.87 ± 0.03 a | 1.97 ± 0.02 b | 2.08 ± 0.03 c |

| Organic Carbon (OC: %) | 3.44 ± 0.04 a | 3.45 ± 0.02 a | 3.46 ± 0.01 a |

| Total Nitrogen (N: %) | 0.40 ± 0.02 a | 0.76 ±0.02 b | 1.12 ± 0.04 c |

| C:N ratio | 8.60 ± 0.10 a | 4.55 ± 0.05 b | 3.10 ± 0.03 c |

| Total Phosphorus (P: %) | 0.35 ± 0.03 a | 0.36 ± 0.02 a | 0.37 ± 0.01 a |

| Total Potassium (K: %) | 0.33 ± 0.04 a | 0.33 ± 0.01 a | 0.31 ± 0.01 a |

| Manganese (Mn: %) | 0.17 ± 0.01 a | 0.18 ± 0.01 a | 0.18 ± 0.01 a |

| Iron (Fe: %) | 0.21 ± 0.02 a | 0.23 ± 0.01 a | 0.25 ± 0.01 b |

| Zinc (Zn: %) | 0.09 ± 0.01 a | 0.10 ± 0.01 a | 0.10 ± 0.01 a |

| Properties (per Plant) | Treatments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | T1 (PGPR) | T2 (5 g/Kg B) | T3 (5 g/Kg B + PGPR) | T4 (10 g/Kg B) | T5 (10 g/Kg B + PGPR) | |

| Cauliflower Yield (g) | 360.50 ± 3.76 a | 380.75 ± 3.20 b | 410.92 ± 6.15 c | 520.45 ± 8.82 c | 510.02 ± 5.30 c | 550.11 ± 10.05 d |

| Fresh Plant Biomass (Kg) | 1.10 ± 0.07 a | 1.16 ± 0.02 a | 1.20 ± 0.06 a | 1.47 ± 0.05 b | 1.38 ± 0.03 b | 1.66 ± 0.04 c |

| Dry Plant Biomass (g) | 98.10 ± 1.10 a | 105.10 ± 2.05 b | 108.56 ± 2.09 b | 132.30 ± 1.12 d | 124.21 ± 3.10 c | 149.40 ± 4.18 e |

| Plant Height (cm) | 14.65 ± 0.17 a | 16.44 ± 0.06 b | 17.84 ± 0.22 c | 21.25 ± 0.10 d | 18.46 ± 0.22 c | 22.09 ± 0.14 d |

| Root Length (cm) | 9.57 ± 0.05 a | 9.78 ± 0.09 b | 10.10 ± 0.07 c | 10.76 ± 0.13 d | 9.80 ± 0.08 b | 11.20 ± 0.05 d |

| Plant Spread (cm) | 20.09 ± 0.28 a | 22.38 ± 0.15 b | 23.37 ± 0.26 c | 26.55 ± 0.42 d | 24.91 ± 0.25 c | 28.35 ± 0.18 e |

| Number of Leaves | 8.50 ± 0.50 a | 8.50 ± 0.50 a | 9.50 ± 0.50 ab | 11.00 ± 1.00 bc | 10.50 ± 0.50 b | 12.50 ± 0.50 c |

| Properties | Treatments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | T1 (PGPR) | T2 (5 g/Kg B) | T3 (5 g/Kg B + PGPR) | T4 (10 g/Kg B) | T5 (10 g/Kg B + PGPR) | |

| Total Chlorophyll (TC: mg/g) | 1.57 ± 0.02 a | 1.90 ± 0.05 b | 1.86 ± 0.03 b | 3.02 ± 0.06 cd | 2.89 ± 0.04 c | 3.13 ± 0.07 d |

| Superoxide Dismutase (SOD: µg/g) | 62.49 ± 3.50 b | 52.09 ± 2.71 a | 84.98 ± 4.10 cd | 73.28 ± 0.90 bc | 92.66 ± 5.15 d | 79.12 ± 1.29 c |

| Catalase (CAT: µg/g) | 32.08 ± 0.74 a | 34.22 ± 1.03 a | 45.02 ± 1.65 bc | 40.93 ± 0.82 b | 64.24 ± 3.60 d | 55.70 ± 2.52 c |

| Peroxidase (POD: µg/g) | 12.36 ± 0.04 a | 14.23 ± 0.16 b | 20.14 ± 0.54 c | 26.05 ± 1.10 d | 24.08 ± 0.85 d | 30.18 ± 0.37 e |

| Total Phenolics (TP: mg/g) | 11.20 ± 0.13 a | 13.56 ± 0.08 bc | 12.09 ± 0.06 b | 16.88 ± 0.24 d | 14.58 ± 0.16 c | 19.50 ± 0.31 e |

| Ascorbic Acid (AA: mg/g) | 6.82 ± 0.02 a | 8.21 ± 0.05 b | 10.18 ± 0.08 c | 13.04 ± 0.12 e | 12.05 ± 0.20 d | 14.18 ± 0.55 e |

| Total Carotenoids (TCT: µg/100 g) | 80.50 ± 2.53 a | 91.58 ± 4.32 a | 101.25 ± 7.21 b | 121.87 ± 5.92 c | 110.39 ± 6.07 b | 150.17 ± 8.20 d |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Širić, I.; Eid, E.M.; Taher, M.A.; El-Morsy, M.H.E.; Osman, H.E.M.; Kumar, P.; Adelodun, B.; Abou Fayssal, S.; Mioč, B.; Andabaka, Ž.; et al. Combined Use of Spent Mushroom Substrate Biochar and PGPR Improves Growth, Yield, and Biochemical Response of Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis): A Preliminary Study on Greenhouse Cultivation. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8090830

Širić I, Eid EM, Taher MA, El-Morsy MHE, Osman HEM, Kumar P, Adelodun B, Abou Fayssal S, Mioč B, Andabaka Ž, et al. Combined Use of Spent Mushroom Substrate Biochar and PGPR Improves Growth, Yield, and Biochemical Response of Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis): A Preliminary Study on Greenhouse Cultivation. Horticulturae. 2022; 8(9):830. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8090830

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠirić, Ivan, Ebrahem M. Eid, Mostafa A. Taher, Mohamed H. E. El-Morsy, Hanan E. M. Osman, Pankaj Kumar, Bashir Adelodun, Sami Abou Fayssal, Boro Mioč, Željko Andabaka, and et al. 2022. "Combined Use of Spent Mushroom Substrate Biochar and PGPR Improves Growth, Yield, and Biochemical Response of Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis): A Preliminary Study on Greenhouse Cultivation" Horticulturae 8, no. 9: 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8090830

APA StyleŠirić, I., Eid, E. M., Taher, M. A., El-Morsy, M. H. E., Osman, H. E. M., Kumar, P., Adelodun, B., Abou Fayssal, S., Mioč, B., Andabaka, Ž., Goala, M., Kumari, S., Bachheti, A., Choi, K. S., & Kumar, V. (2022). Combined Use of Spent Mushroom Substrate Biochar and PGPR Improves Growth, Yield, and Biochemical Response of Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis): A Preliminary Study on Greenhouse Cultivation. Horticulturae, 8(9), 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8090830