A Lignin-Rich Extract of Giant Reed (Arundo donax L.) as a Possible Tool to Manage Soilborne Pathogens in Horticulture: A Preliminary Study on a Model Pathosystem

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolates of Fungi and Oomycetes

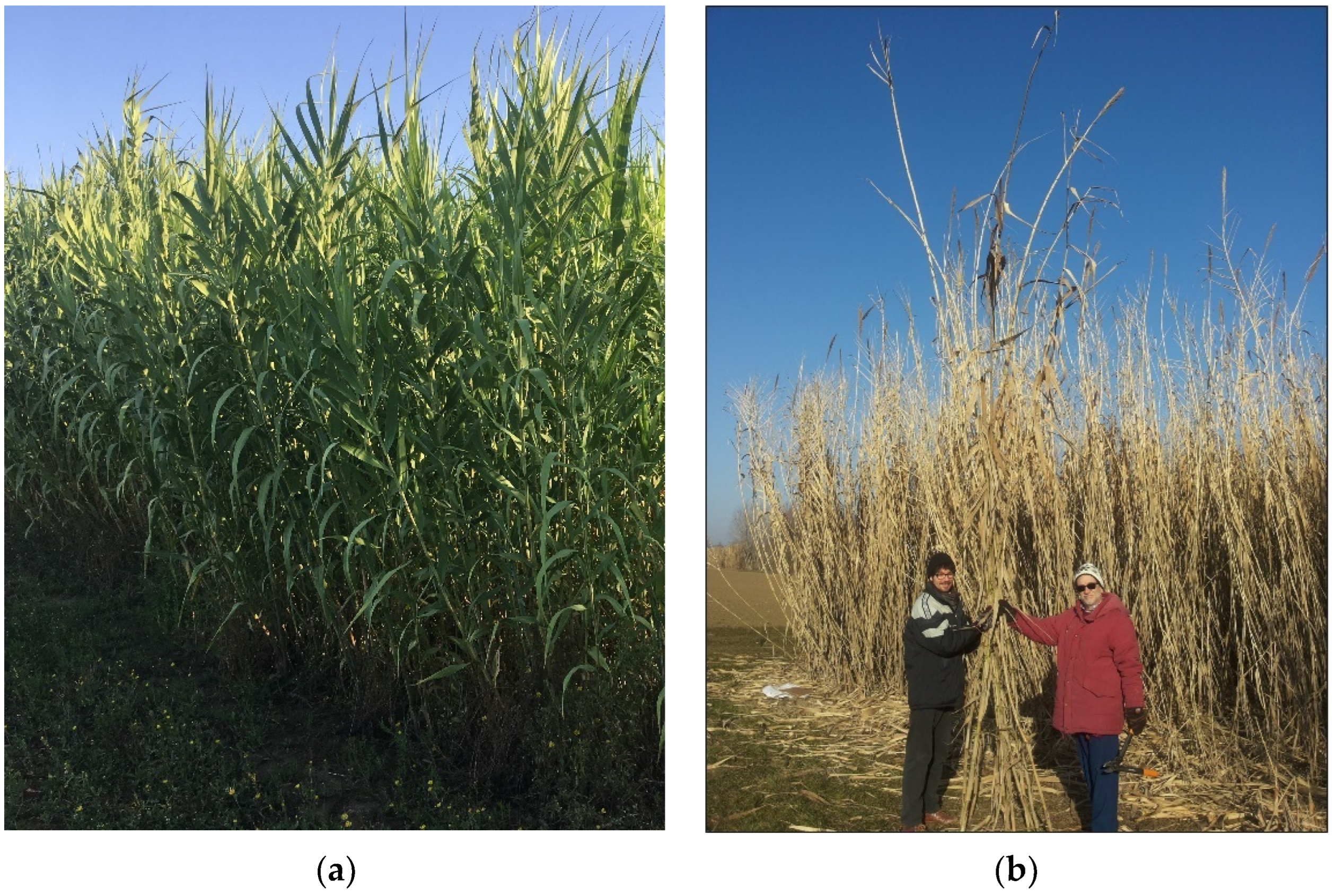

2.2. Giant Reed Meal, Seeds, and Growth Substrate

2.3. Experimental Design

- (A)

- Preparation and chemical characterization of a lignin-rich extract from giant reed dry biomass;

- (B)

- Preliminary tests:

- -

- Toxicity tests of the extract towards fungi and oomycetes on poisoned PDA plates;

- -

- Toxicity test of the extract towards P. ultimum in peat;

- -

- Sensitivity tests of zucchini to the extract on filter paper, in peat, and in sand;

- -

- Pathogenicity test of P. ultimum on zucchini in sand.

- (C)

- Distribution analysis of the lignin-derived polyphenols in peat and sand treated with the extract;

- (D)

- Evaluation of the extract efficacy in the P. ultimum–zucchini pathosystem in a growth substrate.

2.4. Giant Reed Extract Preparation and Characterization

2.5. Toxicity Tests of the Extract towards Fungi and Oomycetes

2.6. Toxicity Test of the Extract towards Pythium ultimum 22 in Peat

2.7. Sensitivity Test of Zucchini to the Extract

2.8. Pathogenicity Test of P. ultimum 22 towards Zucchini

2.9. Determination of the Lignin-Derived Polyphenols in Treated Peat and Sand

2.10. Assessment of the Extract Efficacy in the P. ultimum 22–Zucchini Pathosystem

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Extract Characterization

3.2. Toxicity of the Extract towards Fungi and Oomycetes

3.3. Sensitivity Test of Zucchini to the Giant Reed Extract

3.4. Lignin-Derived Polyphenol Distribution in Peat and Sand

3.5. Extract Efficacy in the P. ultimum 22–Zucchini Patho-System

4. Discussion

4.1. Extract Characterization

4.2. Toxicity of the Extract towards Fungi and Oomycetes

4.3. Sensitivity of Zucchini to the Giant Reed Extract

4.4. Lignin-Derived Polyphenol Distribution in Peat and Sand

4.5. Extract Efficacy in the P. ultimum–Zucchini Pathosystem

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haas, D.; Défago, G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellemi, D.O.; Gamliel, A.; Katan, J.; Subbarao, K.V. Development and deployment of systems-based approaches for the management of soilborne plant pathogens. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwinn, K.D. Bioactive natural products in plant disease control. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Rahman, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 56, pp. 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaker, M. Natural plant products as eco-friendly fungicides for plant diseases control- a review. Agriculturists 2016, 14, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño, J.; Narváez, D.M.; Mosquera, O.M.; Correa, Y.M. Antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic activities of eight Asteraceae and two Rubiaceae plants from Colombian biodiversity. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2006, 37, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, J.H.; Locke, J.C. Effect of botanical extracts on the population density of Fusarium oxysporum in soil and control of Fusarium wilt in the greenhouse. Plant Dis. 2000, 84, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuveni, M.; Sanches, E.; Barbier, M. Curative and suppressive activities of essential tea tree oil against fungal plant pathogens. Agronomy 2020, 10, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, J.; Norrie, J.; Punja, K.Z. Commercial extract from the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum reduces fungal diseases in greenhouse cucumber. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, I.; Scurlock, J.M.; Lindvall, E.; Christou, M. The development and current status of perennial rhizomatous grasses as energy crops in the US and Europe. Biomass Bioenerg. 2003, 25, 335–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, G. Giant reed (Arundo donax L.) from ornamental plant to dedicated bioenergy species: Review of economic prospects of biomass production and utilization. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. 2018, 24, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al-Snafi, E.A. The constituents and biological effects of Arundo donax—A review. Int. J. Phytopharm. Res. 2015, 6, 34–40. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:202637327 (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Ceotto, E.; Vasmara, C.; Marchetti, R.; Cianchetta, S.; Galletti, S. Biomass and methane yield of giant reed (Arundo donax L.) as affected by single and double annual harvest. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenerg. 2021, 13, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasmara, C.; Cianchetta, S.; Marchetti, R.; Ceotto, E.; Galletti, S. Potassium hydroxyde pre-treatment enhances methane yield from giant reed (Arundo donax L.). Energies 2021, 14, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianchetta, S.; Nota, M.; Polidori, N.; Galletti, S. Alkali pre-treatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of Arundo donax for single cell oil production. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2019, 18, 1693–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Cianchetta, S.; Polidori, N.; Vasmara, C.; Ceotto, E.; Marchetti, R.; Galletti, S. Single cell oil production from hydrolysates of alkali pre-treated giant reed: High biomass-to-lipid yields with selected yeasts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 178, 114596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quave, L.C.; Plano, R.W.L.; Pantuso, T.; Bennet, C.B. Effects of extracts from Italian medicinal plants on planktonic growth, biofilm formation and adherence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 118, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirkani, A.; Mozaffari, M.; Zarei, M. Antimicrobial effects of 14 medicinal plant species of Dashti in Bushehr province. Iran. S. Med. J. 2014, 17, 49–57. Available online: http://ismj.bpums.ac.ir/article-1-504-en.html (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Temiz, A.; Akbas, S.; Panov, D.; Terziev, N.; Alma, M.H.; Parlak, S.; Kose, G. Chemical composition and efficiency of bio-oil obtained from giant cane (Arundo donax L.) as a wood preservative. Bioresources 2013, 8, 2084–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corato, U.; Viola, E.; Arcieri, G.; Valerio, V.; Cancellara, A.F.; Zimbardi, F. Antifungal activity of liquid waste obtained from the detoxification of steam-exploded plant biomass against plant pathogenic fungi. Crop Prot. 2014, 55, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordobil, O.; Herrera, R.; Yahyaoui, M.; Ilk, S.; Kaya, M.; Labidi, J. Potential use of kraft and organosolv lignins as a natural additive for healthcare of products. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 24525–24533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Dong, M.; Lu, Y.; Turley, A.; Jin, T.; Wu, C. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of lignin from residue of corn stover to ethanol production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 34, 1630–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, U.M.; Ji, N.; Li, H.; Wu, Q.; Song, C.; Liu, Q.; Ma, D.; Lu, X. Can lignin be transformed into agrochemicals? Recent advances in the agricultural applications of lignin. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 170, 113646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzettaufficiale.it. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2001/01/26/21/sg/pdf (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Miller, G.L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianchetta, S.; Galletti, S.; Burzi, P.L.; Cerato, C. A novel microplate-based screening strategy to assess the cellulolytic potential of Trichoderma strains. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2010, 107, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righini, H.; Francioso, O.; Di Foggia, M.; Prodi, A.; Martel Quintana, A.; Roberti, R. Tomato seed biopriming with water extracts from Anabaena minutissima, Ecklonia maxima and Jania adhaerens as a new agro-ecological option against Rhizoctonia solani. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 281, 109921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannwischer, M.E.; Mitchell, D.J. The influence of a fungicide on the epidemiology of black shank of tobacco. Phytopathology 1978, 68, 1760–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTA. International Rules for Seed Testing; International Seed Testing Association: Zürich, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Don, R. ISTA Handbook on Seedling Evaluation; International Seed Testing Association: Zürich, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Shan, X.-Q.; Mu, H. Influences of lignin from paper mill sludge on soil properties and metal accumulation in wheat. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2004, 40, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Li, S.X. Nitrate N loss by leaching and surface runoff in agricultural land: A global issue (a review). Adv. Agron. 2019, 156, 159–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassi o Di Nasso, N.; Roncucci, N.; Triana, F.; Tozzini, C.; Bonari, E. Seasonal nutrient dynamics and biomass quality of giant reed (Arundo donax L.) and miscanthus (Miscanthus × giganteus Greef et Deuter) as energy crops. Ital. J. Agron. 2011, 6, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhli, R.; Khatteli, H.; Ridha, L.; Taamallah, H. Agronomic application of olive mill waste water: Short-term effect on soil chemical properties and barley performance under semiarid Mediterranean conditions. Int. J. Environ. Qual. 2018, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffar, M.; Pang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Zou, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Korai, R.M.; Li, X. Wheat straw pretreatment with KOH for enhancing biomethane production and fertilizer value in anaerobic digestion. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 24, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordas, C. Role of nutrients in controlling plant diseases in sustainable agriculture. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 28, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cheng, J.J. Hydrolysis of lignocellulosic materials for ethanol production: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 83, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, S.; Vancov, T. Optimisation of dilute alkaline pretreatment for enzymatic saccharification of wheat straw. Biomass Bioenerg. 2011, 35, 3094–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiraud, P.; Steiman, R.; Seiglemurandi, F.; Benoitguyod, J.L. Comparison of the toxicity of various lignin-related phenolic compounds toward selected fungi perfecti and fungi imperfecti. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 1995, 32, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianchetta, S.; Di Maggio, B.; Burzi, P.L.; Galletti, S. Evaluation of selected white-rot fungal isolates for improving the sugar yield from wheat straw. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 173, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletti, S.; Sala, E.; Leoni, O.; Burzi, P.L.; Cerato, C. Trichoderma spp. tolerance to Brassica carinata seed meal for a combined use in biofumigation. Biol. Control 2008, 45, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavi, G.B.; Devi, G.U. Effect of combined application of biofumigant, Trichoderma harzianum and Pseudomonas fluorescens on Rhizoctonia solani f. sp. sasakii. Indian Phytopathol. 2018, 71, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Hu, H.Y.; Sakoda, A.; Sagehashi, M. Isolation and characterization of antialgal allelochemicals from Arundo donax L. Allelopath. J. 2010, 25, 357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Romann, S. Allelopathic effect of Arundo donax, a mediterranean invasive grass. Plant Omics J. 2015, 8, 287–288. Available online: https://www.pomics.com/aburomman_8_4_2015_287_291.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Popa, V.I.; Dumitru, M.; Volf, I.; Anghel, N. Lignin and polyphenols as allelochemicals. Ind. Crops Prod. 2008, 27, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savy, D.; Cozzolino, V.; Nebbioso, A.; Drosos, M.; Nuzzo, A.; Mazzei, P.; Piccolo, A. Humic-like bioactivity on emergence and early growth of maize (Zea mays, L.) of water-soluble lignins isolated from biomass for energy. Plant Soil 2016, 402, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balas, A.; Popa, V.I. The influence of natural aromatic compounds on the development of Lycopersicon esculentum plantlets. Bioresources 2007, 2, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckay, G. Peat for environmental applications: A review. Dev. Chem. Eng. Miner. Process. 1996, 4, 127–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmaruzzaman, M. Adsorption of phenolic compounds on low-cost adsorbents: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 143, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, H.; Marques, M.; Svensson, B.M.; Mårtensson, L.; Bhatnagar, A.; Hogland, W. Treatment of wood leachate with high polyphenols content by peat and carbon-containing fly ash filters. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 53, 2041–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crini, G. Non-conventional low-cost adsorbents for dye removal: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 1061–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, O.S.; Bello, I.A.; Adegoke, K.A. Adsorption of dyes using different types of sand: A review. S. Afr. J. Chem. 2013, 66, 117–129. Available online: https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/EJC134491 (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Zschiegner, H. Plant Tonic for Induction and Improvement of Resistance. DE4404860A1, 31 August 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mauch-Mani, B.; Baccelli, I.; Luna, E.; Flors, V. Defense priming: An adaptive part of induced resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017, 68, 485–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.N. Development of alternative strategies for management of soilborne pathogens currently controlled with methyl bromide. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2003, 41, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panth, M.; Hassler, S.C.; Baysal-Gurel, F. Methods for management of soilborne diseases in crop production. Agriculture 2020, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Isolate | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Soilborne pathogenic oomycetes and fungi | Pythium ultimum 16 | Sugar beet |

| Pythium ultimum 22 | Sugar beet | |

| Phytophthora cactorum | Strawberry | |

| Ceratobasidium sp. RH3 | Strawberry | |

| Rhizoctonia solani DAF3001 | Green bean | |

| Sclerotium rolfsii 1 | Sugar beet | |

| Sclerotium rolfsii 2 | Potato | |

| Sclerotinia sclerotiorum MA3 | Alfalfa | |

| Phoma betae | Sugar beet | |

| Fusarium oxysporum L1 | Tomato | |

| Fusarium oxysporum 11.22 | Tomato | |

| Airborne pathogenic fungi | Botrytis cinerea 1 | Strawberry |

| Botrytis cinerea 2 | Green bean | |

| Alternaria alternata 1 | Potato | |

| Alternaria alternata 2 | Tomato | |

| Wood decay fungi | Phanerochaete chrysosporium D85242T | VTT, Finland |

| Trametes versicolor D83211 | VTT, Finland | |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | Funghi Mara, Italy | |

| Pathogenic Trichoderma species | Trichoderma pleuroticola 488 | P. ostreatus substrate |

| Trichoderma pleuroti 498 | P. ostreatus substrate | |

| Nonpathogenic Trichoderma species | Trichoderma gamsii IMO5 | Peach rhizosphere |

| Trichoderma afroharzianum B75 | Sugar beet rhizosphere |

| Composition Parameters | Mean Values (sd) |

|---|---|

| Total solids (%DW) 2 | 95.51 (0.02) |

| Cellulose (%DW) | 41.2 (1.5) |

| Hemicellulose (%DW) | 22.5 (0.8) |

| Lignin (%DW) | 10.9 (0.5) |

| Ash (%DW) | 5.19 (0.01) |

| Total C (%DW) | 44.6 (0.60) |

| Total N (%DW) | 0.37 (0.05) |

| Total P (%DW) | 0.05 (0.00) |

| C/N (mol/mol) 3 | 142 (21) |

| pH in water | 5.4 (0.5) |

| Composition Parameters 2 | Mean Values (sd) |

|---|---|

| Water (%FM 1) | 94.7 (0.2) |

| Total solids (TS 2) (%FM) | 5.3 (0.2) |

| Volatile solids (%FM) | 2.6 (0.1) |

| Ashes (%FM) | 2.7 (0.1) |

| pH in water | 6.5–7.2 |

| Electrical conductivity (S/m) | 0.30 (0.01) |

| Total P (%FM) | 0.009 (0.002) |

| Total K (%FM) | 0.84 (0.02) |

| Total organic C (%FM) | 2.0 (0.1) |

| C (% TS) | 36 (0.5) |

| N (% TS) | 0.57 (0.1) |

| C:N ratio (weight/weight) | 63 (10) |

| Hydrolysable holocellulose (%FM) | 0.42 (0.02) |

| Free reducing sugars (%FM) | 0.14 (0.04) |

| Lignin-derived polyphenols (%FM) 3 | 1.7 (0.15) |

| Treatment (CFU × 105/g Peat Dry Weight) 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Time from Treatment (h) | Infected | Infected + Treated |

| 0 | 0.91 ab 2 | 1.22 a |

| 48 | 1.09 a | 0.47 b |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galletti, S.; Cianchetta, S.; Righini, H.; Roberti, R. A Lignin-Rich Extract of Giant Reed (Arundo donax L.) as a Possible Tool to Manage Soilborne Pathogens in Horticulture: A Preliminary Study on a Model Pathosystem. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8070589

Galletti S, Cianchetta S, Righini H, Roberti R. A Lignin-Rich Extract of Giant Reed (Arundo donax L.) as a Possible Tool to Manage Soilborne Pathogens in Horticulture: A Preliminary Study on a Model Pathosystem. Horticulturae. 2022; 8(7):589. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8070589

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalletti, Stefania, Stefano Cianchetta, Hillary Righini, and Roberta Roberti. 2022. "A Lignin-Rich Extract of Giant Reed (Arundo donax L.) as a Possible Tool to Manage Soilborne Pathogens in Horticulture: A Preliminary Study on a Model Pathosystem" Horticulturae 8, no. 7: 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8070589

APA StyleGalletti, S., Cianchetta, S., Righini, H., & Roberti, R. (2022). A Lignin-Rich Extract of Giant Reed (Arundo donax L.) as a Possible Tool to Manage Soilborne Pathogens in Horticulture: A Preliminary Study on a Model Pathosystem. Horticulturae, 8(7), 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8070589