Constraints to Cultivation of Medicinal Plants by Smallholder Farmers in South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

3. Findings of the Review

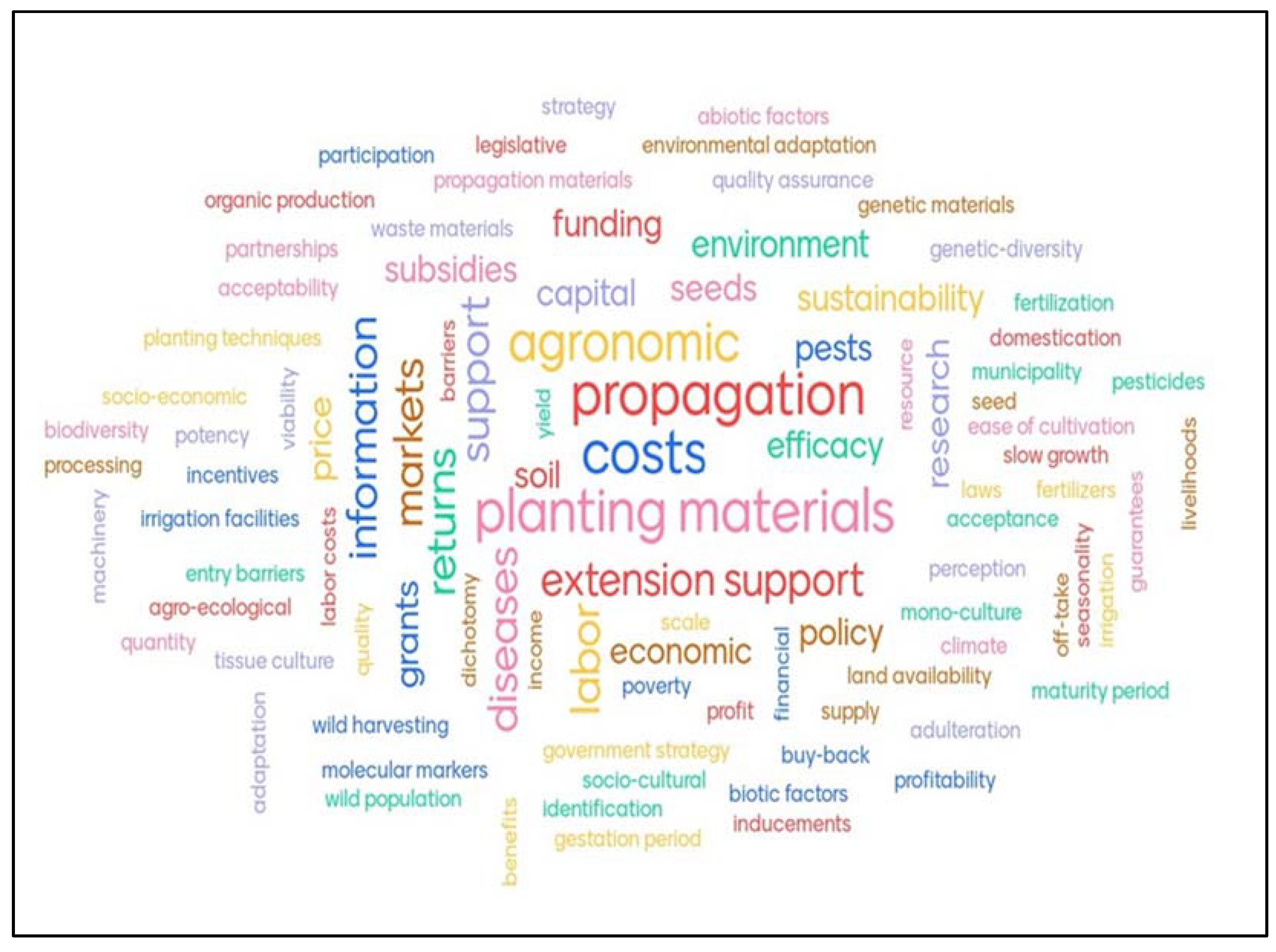

3.1. Key Constraints Identified

3.2. Usefulness of Medicinal Plants in South Africa

3.3. Economic Importance of Medicinal Plants in South Africa

3.4. Related Studies on Cultivation of Medicinal Plants in South Africa

4. Discussion

4.1. Cultivation of Medicinal Plants as a Conservation Strategy

4.2. Agronomic and Agro-Ecological Issues

4.3. Socio-Economic Considerations

4.4. Socio-Cultural Considerations

4.5. Other Hindrance to Smallholder Involvement

4.6. Status of Medicinal Plants Cultivation in Other Countries

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anthonio, G.D.; Tesser, C.D.; Moretti-Pires, R.O. Contributions of Medicinal Plants to Care and Health Promotion in Primary Healthcare. Interface 2013, 17, 615–633. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.L.; Yu, H.; Luo, H.M.; Wu, Q.; Li, C.F.; Steinmetz, A. Conservation and Sustainable Use of Medicinal Plants: Problems, Progress and Prospects. Chin. Med. 2016, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, R. Application of medicinal plants: From past to present. MOJ Biol. Med. 2017, 1, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kumar, S.; Bhatnagar, T. Studies to Enhance the Shelf Life of Fruits using Aloe Vera Based Herbal Coatings: A Review. Int. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 5, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Panday, A.; Singh, S. Aloe Vera: A Systematic Review of its Industrial and Ethno-Medicinal Efficacy. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Allied Sci. 2016, 5, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lerotholi, L.; Chaudhary, S.K.; Combrink, S.; Viljoen, A. Bush tea (Athrixia phylicoides): A review of the traditional uses, bioactivity and phytochemistry. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 110, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushnie, T.P.; Cushnie, B.; Lamb, A.J. Alkaloids: An overview of their antibacterial, antibiotic-enhancing and anti-virulence activities. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 44, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egamberdieva, D.; Wirth, S.; Behrendt, U.; Ahmad, P.; Berg, G. Antimicrobial Activity of Medicinal Plants Correlates with the Proportion of Antagonistic Endophytes. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbuni, Y.M.; Wang, S.; Mwangi, B.N.; Mbari, N.J.; Musili, P.M.; Walter, N.O.; Hu, G.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Q. Medicinal Plants and Their Traditional Uses in Local Communities around Cherangani Hills, Western Kenya. Plants 2020, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher, H.; Busmann, R.; de Boer, H.D. Traditional use of medicinal plants among Kalasha, Ismaeli and Sunni groups in Chitral District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Pakistan. J. Ethnopharm. 2016, 188, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bareetseng, S. Community Involvement in the Commercialisation of Medicinal Plant Species. The Case Studies: Lippia javanica and Elephantorrhiza elephantine. A CSIR Presentation, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa. 2015. Available online: https://www.dffe.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/publications/communityinvolvement_commercialisation_medicinalplantspecies.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Sher, H.; Bankworth, M.E. Economic development through medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) cultivation in Hindu Kush Himalaya Mountains of District Swat, Pakistan. J. Mt. Sci. 2015, 12, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousan, L.M.; El-Uzaizi, S.F. Farmer’s knowledge level and training needs toward the production and conservation of me-dicinal herbal plants in Jordan. J. Med. Plants Res. 2016, 10, 351–359. [Google Scholar]

- Shakya, A.K. Medicinal Plants: Future Source of New Drugs. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2016, 4, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rathore, R.; Mathur, A. Entrepreneurship Development in Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: Prospects and Challenges. Int. J. Econ. Plants 2018, 5, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agribook Digital. Indigenous Medicinal Plants. Available online: https://agribook.co.za/forestry-and-industrial-crops (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- DAFF-Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. A Profile of the South African Traditional Medicines Value Market Chain. Republic of South Africa. Available online: https://www.nda.agric.za/doaDev/sideMenu/Marketing/ (accessed on 6 March 2020).

- Moshi, M.J.; Mhame, P.P. Legislations on Medicinal Plants in Africa. Medicinal Plant Research in Africa; Elsevier Inc.: London, UK, 2013; pp. 843–858. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, A.Z.; Tunon, H.; Khan, N.A.; Mukul, S.A. Commercial Cultivation by Farmers of Medicinal Plants in Northern Bang-ladesh. Eur. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 4, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ndou, P.; Taruvinga, B.; Mofokeng, M.M.; Kruger, F.; Du Ploy, C.P.; Venter, S.L. Value Chain Analysis of Medicinal Plants in South Africa. Ethno-Medicine 2019, 13, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, E. Health and Wealth from Medicinal Aromatic Plants. Diversification Booklet No. 17; Rural Infrastructure and Agro-Industries Division, FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011; ISBN 978-92-5-107070-3. [Google Scholar]

- Volenzo, T.; Odiyo, J. Integrating endemic medicinal plants into the global value chains: The ecological degradation challenges and opportunities. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astutik, S.; Pretzsch, J.; Kimengsi, J.N. Asian Medicinal Plants’ Production and Utilization Potentials: A Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, E.R.; Osayi, K.K. Factors Affecting the Utilization of Herbal Medicine as a Livelihood Alternative among Residents of Imo State: The Role of Social Work Professionals. IOS J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2016, 21, 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dar, R.A.; Shahnawaz, M.; Qazi, P.H. General Overview of Medicinal Plants: A Review. J. Phytopharm. 2017, 6, 349–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwafemi, R.A.; Olawale, A.I.; Alagbe, J.O. Recent trends in the utilization of medicinal plants as growth promoters in poultry nutrition. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 4, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Reviriego, I.; Gonzalez-Segura, L.; Fernandez-Llamazarez, A.; Howard, P.L.; Molina, J.; Reyes-Garcia, V. Social Organization Influences the Exchange and Species Richness of Medicinal Plants in Amazonian Home-gardens. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavimbela, T.; Viljoen, A.; Veermaak, I. Differentiating between Agathosma betulina and Agathosma crenulate—A quality control perspective. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2014, 1, e8–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, R.A.; Prinsloo, G. Commercially Important Medicinal Plants of South Africa: A Review. J. Chem. 2013, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisamen, B. Introduction and literature review. In Medicinal Effects of Agathosma (Buchu) Extracts; Huisamen, B., Ed.; AOSIS: Cape Town, South Africa, 2019; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahomoodally, M.F. Traditional Medicines in Africa: An Appraisal of Ten Potent African Medicinal Plants. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 617459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joubert, E.; de Beer, D. Rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) beyond the farm gate: From herbal tea to potential phyto-pharmaceutical. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2011, 77, 869–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwafor, I.; Manduna, I. Local processing methods for commonly used medicinal plants in South Africa. Med. Plants-Int. J. Phytomed. Relat. Ind. 2021, 13, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenya, S.S.; Potgieter, M.J. Medicinal plants cultivated in Bapedi traditional healers’ home-gardens, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 11, 126–132.35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Van Wyk, B.-E.; Vermaak, I.; Viljoen, A.M. Cape aloes—A review of the phytochemistry, pharmacology and com-mercialisation of Aloe ferox. Phytochem. Lett. 2012, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifu, E.; Teket, D. Introduction and expansion of Moringa oleifera Lam. in Botswana: Current status and potential for com-mercialization. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 129, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshabalala, T.; Ncube, B.; Madala, N.E.; Nyakudya, T.T.; Moyo, H.P.; Sibanda, M.; Ndhlala, A.R. Scribbling the Cat: A Case of the Miracle Plant, Moringa oleifera. Plants 2019, 8, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurib-Fakim, A.; Mahomoodally, M.F. African flora as potential sources of medicinal plants: Towards the chemotherapy of major parasitic and other infectious diseases- a review. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 6, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E. African Herbal Pharmacopeia; Brendler, T., Eloff, L.N., Gurib-Fakim, A., Phillips, L.D., Eds.; Association for African Medicinal Plants Standards (AAMPS) Publishing: Port Luis, Mauritius, 2010; ISBN 978-99903-89-09-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mncwangi, N.; Chen, W.; Vermaak, I.; Viljoen, A.M.; Gericke, N. Devil’s claw-a review of the ethno-botany, phytochemistry and biological activity of Harpagophytum procumbens. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143, 755–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyo, M.; van Staden, J. Medicinal properties and conservation of Pelargonium sidoides DC. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 152, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helfer, M.; Koppensteiner, H.; Schneider, M.; Rebensburg, S.; Forcisi, S.; Müller, C.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Schindler, M.; Brack-Werner, R. The Root Extract of the Medicinal Plant Pelargonium sidoides as a Potent HIV-1 Attachment Inhibitor. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innovus. Cultivation Method for the Medically Valuable Pelargonium. Available online: https://www.innovus.co.za/technologies/medicine-and-health-1/phytomedicine-solutions/cultivation-method-for-the-medically-valuable-pelargonium.html (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Fouche, G.; van Rooyen, S.; Faleschini, T. Siphonochilus aethiopicus, a traditional remedy for the treatment of allergic asthma. Int. J. Genuine Trad. Med. 2013, 3, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adebayo, S.A.; Amoo, S.O.; Mokgehle, S.N.; Aremu, A.O. Ethnomedicinal uses, biological activities, phytochemistry and conservation of African ginger (Siphonochilus aethiopicus): A commercially important and endangered medicinal plant. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 266, 113459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, B.E. The potential of South African plants in the development of new medicinal products. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2011, 77, 812–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwu, M.M. Pharmacognostical Profile of Selected Medicinal Plants: Handbook of African Medicinal Plants, 2nd ed.; Routledge and CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; SBN: 9781466571983; ISBN 9781466571976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, P.; Kunyane, P.; Selepe, M.A.; Eloff, J.N.; Niemand, J.; Louw, A.I.; Maharaj, V.J.; Birkholtz, L.B. Bioassay-guided isola-tion and identification of gametocytocidal compounds from Artemisia afra (Asteraceae). Malar. J. 2019, 18, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungqu, P.; Oyedeji, O.O.; Oyedeji, A.O. Chemical Composition of Hypoxis hemerocallidea Fisch. and C.A. Mey from Eastern Cape, South Africa. In Chemistry for a Clean and Healthy Planet, Proceedings of International Conference on Pure and Applied Chemistry, Eastern Cape, South Africa, 2–6 July 2018; Ramasami, P., Gupta, B.M., Jhaumeer, L.S., Li Kam, W.H., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 111–121. ISBN 978-3-030-20282-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroyi, A. A synthesis and review of medicinal uses, phytochemistry and biological activities of Helichrysum odoratissimum (L.) Sweet. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2019, 12, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Extracts and Compositions of Helichrysum odoratissumum for Preventing and Treating Skin Cancers. 2015. Available online: https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/51/39/56/c739d2695f065d/WO2015049666A1.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Mugomeri, E.; Chatanga, P.; Raditladi, T.; Makara, M.; Tirirai, C. Ethnobotanical study and conservation status of local medic-inal plants: Towards a repository and monograph of herbal medicines in Lesotho. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 13, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaberi, M.; Sahebkar, A.; Azizi, N.; Emami, S.A. Everlasting flowers: Phytochemistry and pharmacology of the genus Heli-chrysum. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 138, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Krygsman, A. Hoodia gordonii: To eat, or not to eat. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 987–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermaak, L.; Viljoen, A. Fight fair in the fight against fat: “real” versus “fake” Hoodia. SA Pharm. J. 2012, 79, 54–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mander, M.; Ntuli, L.; Diederichs, N. Economics of the traditional medicine trade in South Africa: Health care delivery. S. Afr. Health Rev. 2007, 2007, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Rankoana, S.A. Sustainable Use and Management of Indigenous Plant Resources: A Case of Mantheding Community in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Sustainability 2016, 8, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xego, S.; Kambizi, L.; Nchu, F. Threatened medicinal plants of South Africa: Case of the family hyacinthacea. Afr. J. Tradit. Complementary Altern. Med. 2016, 13, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wiersum, K.F.; Dold, A.P.; Husselman, M.; Cocks, M. Cultivation of medicinal plants as a tool for bio-diversity conservation and poverty alleviation in the Amatola Region, South Africa. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants; Bogers, R.J., Craker, L.E., Lange, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 17, pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tanga, M.; Lewu, F.B.; Oyedeji, O.A.; Oyedeji, O.O. Cultivation of Medicinal Plants in South Africa: A Solution to Quality As-surance and Consistent Availability of Medicinal Plant Materials for Commercialization. Acad. J. Med. Plants 2018, 6, 168–177. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, L.; Reid, A.M.; Moll, E.J.; Hockings, M.T. Perspectives of wild medicine harvesters from Cape Town, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2017, 113, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorhosseini, S.A.; Fallahi, E.; Damalas, C.A.; Allahyari, M.S. Factors Affecting the Demand for medicinal Plants: Implications for Rural Development in Rasht, Iran. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, A.; van Staden, J. The need for cultivation of medicinal plants in Southern Africa. Outlook Agric. 2000, 29, 283–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keirungi, J.; Fabricius, C. Selecting medicinal plants for cultivation at Nqabara on the Eastern Cape Wild Coast, South Africa: Research in action. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2005, 101, 497–501. [Google Scholar]

- McGaw, L.; Jager, A.; Grace, O.; Fennel, C.; van Staden, J. Medicinal Plants. In Ethics in Agriculture—An African Perspective; Van Niekerk, A., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; ISBN 978-1-4020-2989-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshabalala, T.; Ncube, B.; Moyo, H.P.; Abdel-Rahman, E.M.; Mutanga, O.; Ndhlala, A.R. Predicting the spatial suitability distri-bution of Moringa oleifera cultivation using analytical hierarchical process modelling. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 129, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, A.S.; Prinsloo, G. Medicinal plant harvesting, sustainability and cultivation in South Africa. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 227, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroyi, A. Diversity of use and local knowledge of wild and cultivated plants in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2017, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzerefos, C.M.; Witkowski, T.F.; Kremeh-Kohne, S. Aiming for the biodiversity target with the social welfare arrow: Medicinal and other useful plants from a critically endangered grassland ecosystem in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 24, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippmann, U.; Leaman, D.; Cunningham, A. A Comparison of Cultivation and Wild Collection of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants under Sustainability Aspects. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants; Bogers, R.J., Craker, L.E., Lange, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Craven, D.; Winter, M.; Hotzel, K.; Gaikwad, J.; Eisenhauer, N.; Hohmuth, M.; König-Ries, B.; Wirth, C. Evolution of inter-disciplinarity in biodiversity science. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 6744–6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurgiu, R.M.; Morar, G.A.; Dumitras, A.; Boanca, P.; Duda, B.M.; Moldovan, C. Study regarding the suitability of cultivating medicinal plants in hydroponic systems in controlled environment. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 46, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Egamberdieva, D.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A. Medicinal Plants and PGPR: A New Frontier for Phytochemicals. In Plant-Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) and Medicinal Plants. Soil Biology; Egamberdieva, D., Shrivastava, S., Varma, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dajic-Stevanovic, Z.; Pljevljakusic, D. Challenges and Decision Making in Cultivation of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of the World; Máthé, Á., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 145–164. ISBN 978-94-017-9810-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishe, M.; Asfaw, Z.; Giday, M. Review on value chain analysis of medicinal plants and the associated challenges. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2016, 4, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Amujoyegbe, B.J.; Agbedahunsi, J.M.; Amujoyegbe, O.O. Cultivation of medicinal plants in developing nations: Means of conservation and poverty alleviation. Int. J. Med. Aromat. Plants 2012, 2, 345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, N.R.; Smith, G.F. Informing and influencing the interface between biodiversity science and biodiversity policy in South Africa. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2011, 166, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEFF-RSA. Bio-Prospecting Economy. Department: Environment, Forestry and Fisheries. Republic of South Africa. 2020. Available online: https://www.environment.gov.za/projectsprogrammes/bioprospectingeconomy (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- SEDA. Research Study to Identify Needs, Opportunities and Challenges of Small and Medium Enterprises in the Traditional Medicine Sector. Final Report, Atalanta Consulting. November 2012. Small Enterprise Development Agency. Available online: http://www.seda.org.za/Publications/Publications/ (accessed on 12 February 2020).

- Nwafor, C.U.; Westhuizen, C. Prospects for Commercialization among Smallholder Farmers in South Africa: A Case Study. J. Rural Soc. Sci. 2020, 35, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, M.; Aremu, O.A.; Van Standen, J. Medicinal plants: An invaluable, dwindling resource in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Eth-nopharmacol. 2015, 174, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netshiluvhi, T.R.; Eloff, J.N. Effect of water stress on antimicrobial activity of selected medicinal plant species. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 102, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanhokwe, M.; Mupangwa, J.; Masika, P.J.; Maphosa, V.; Muchenje, V. Medicinal plants used to control internal and external parasites in goats. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2016, 83, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennel, C.W.; Light, M.E.; Sparg, S.G.; Stafford, G.I.; van Staden, J. Assessing African medicinal plants for efficacy and safety: Agricultural and storage practices. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 95, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinsloo, G.; Nogemane, N. The effect of water availability on chemical composition, secondary metabolites and biological activity in plants. Phytochem. Rev. 2018, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippmann, U.; Leaman, D.J.; Cunningham, A. Impact of cultivation and gathering of medicinal plants on biodiversity: Global trends and issues. In Biodiversity and Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002; Volume 2, pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, S.; Sharma, N.G.; Anil, K.J. Studies on variation in elemental composition in wild and cultivated forms of An-drographis paniculata. Int. J. Chem. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 5, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kamatchi, K.B.; Vigneswari, R. A comparative study on elemental composition in some wild and cultivated medicinal plants. Ann. Plant Sci. 2018, 7, 2418–2422. [Google Scholar]

- Raghu, A.V.; Amruth, M. Cultivation of medicinal plants: Challenges and prospects. In Prospects in conservation of Medicinal Plants; Raghu, A.V., Amruth, M., Mohammed, K.K.V., Raveendran, V.P., Syam, V., Eds.; KSCSTE-Kerala Forest Research Institute: Kerala, India, 2018; ISBN 81-85041-99-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lubbe, A.; Verpoorte, R. Cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants for specialty industrial materials. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 34, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofokeng, M.M.; Sehlola, D.M.; Araya, H.T.; Amoo, S.O.; du Plooy, C.P. A new record of mealybugs (Paracoccus burnerae Brain–Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) and leafhoppers (Mngenia angusta Theron–Cicadellidae: Coelidiinae) on a Southern African medicinal plant, Greyia radlkoferi. Afr. Entomol. 2020, 28, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeng, E.T.; Potgieter, M.J. The trade of medicinal plants by muthi shops and street vendors in the Limpopo Province. S. Afr. J. Med. Plant Res. 2011, 5, 558–564. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, A. Studies on biochemical and physiological aspects in relation to phyto-medicinal qualities and efficacy of the active ingredients during the handling, cultivation and harvesting of the medicinal plants. J. Med. Plant Res. 2009, 3, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Strydom, H.A.; King, N.D. Fuggle and Rabie’s Environmental Management, 2nd ed.; Juta: Clairmont, South Africa, 2013; p. 1142. Available online: https://juta.co.za/catalogue/fuggle-rabies-environmental-management-in-south-africa-3e-print_24846 (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Appiah, K.S.; Oppong, C.P.; Mardani, H.K.; Omari, R.A.; Kpabitey, S. Medicinal Plants Used in the Ejisu-Juaben Municipality, Southern Ghana: An Ethnobotanical Study. Medicines 2019, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, D.A.; Obiri, B.D.; Gyimah, A.; Adam, K.A.; Jimoh, S.O.; Jamnadass, R.H. Ethnobotany, propagation and conservation of medicinal plants in Ghana. GJF 2012, 28, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gurib-Fakim, A. Novel Plant Bio-Resources: Application in Food, Medicine and Cosmetics, 1st ed.; Wiley & Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeswara, R.B.; Syamasundar, K.V.; Rajput, D.K.; Nagaraju, G.; Adinarayana, G. Biodiversity, conservation and cultivation of medicinal plants. J. Pharmacogn. 2012, 3, 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, K.; Chomchalow, N. Production of medicinal plants in Asia. Acta Hortic. 2005, 679, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shengji, P.; Hamilton, A.C.; Lixin, Y.; Huyin, H.; Zhiwei, Y.; Fu, G.; Quangxin, Z. Conservation and development through me-dicinal plants: A case study from Ludian (Northwest Yunnan, China) and presentation of a general model. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 2619–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, R.M.; Mahat, L.; Acharya, R.P.; Bussmann, R.W. Medicinal plants, traditional medicine, markets and management in far-west Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.J.; Jones, J.P.; Annewandter, R.A.; Gibbons, J.M. Cultivation can increase harvesting pressure on overexploited plant populations. Ecol. Appl. 2014, 24, 2050–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, V.S.; Kewlani, P.; Pathak, R.; Bhatt, D.; Bhatt, I.D.; Rawal, R.S.; Sundriyal, R.C.; Nandi, S.K. Criteria and indicators for promoting cultivation and conservation of medicinal and aromatic plants in Western Himalaya, India. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Family | Common Name | Uses | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agathosma betulina (Berg.) Pillans | Rutaceae | Buchu | Antispasmodic, antipyretic, cough remedy, diuretic and to treat urinary tract infections. | [28] |

| Agathosma crenulate (L.) Pillans | Rutaceae | Buchu | Anti-spasmodic, antipyretic, diuretic anti-microbial, anti-inflammatory anti-oxidant, and analgesic effects. | [29,30] |

| Aspalathus linearis (Burm.f.) Dahlg. | Fabaceae | Rooibos | Anti-spasmodic, anti-oxidant, anti-aging, and anti-eczema activities (tea). | [31,32] |

| Sclerocarya birrea (A.Rich.) Hochst. | Anacardiaceae | Morula or Marula | Infertility in females, dysentery, diarrhea, rheumatism, malaria and proctitis, ear nose, and throat conditions. | [33,34] |

| Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don. | Apocynaceae | Periwinkle | Urogenital infections, stomach ache, diabetes mellitus, unsuspected venereal diseases, and rheumatism. | [34] |

| Aloe forex (Mill.) | Xanthorrhoeaceae | Bitter aloe or Cape aloe | Laxative, cuts and burns, emetics, arthritis, stomach pains, and hypertension. | [31,35] |

| Moringa oleifera Lam. | Moringaceae | Moringa | Anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-diabetic properties are used to treat mainly diabetes, high blood pressure, and rheumatism. | [17,32,36,37] |

| Cyclopia genistoides (L.) Vent. | Fabaceae | Honeybush | Anti-cancer, anti-diabetic use, alleviates menopausal symptoms, stomach tonic, expectorant, decongestant. | [31,38,39] |

| Harpagophytum procumbens (Burch.) DC. | Pedaliaciae | Devils claw | Treats rheumatism, arthritis, diabetes, gastrointestinal disturbances, menstrual difficulties, neuralgia, headache, heartburn, and gout. | [31,38,39,40] |

| Pelargonium sidoides DC. | Geraniaceae | Umckaloabo | Disorders of the respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract infections, diarrhea and dysentery, HIV complications. | [31,38,41,42,43] |

| Pelargonium reniforme Curt. | Geraniaceae | Kidney-leaved pelargonium, Rooirabas, | Stomach ailments, bronchitis, dysentery, bloody stool. | [17,41,42] |

| Siphonoculus aethiopicus (Schweinf) B.L. Burt | Zingiberaceae | African ginger | Potential anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating properties, coughs, colds, asthma, headache, candida, malaria, pain, and influenza. | [17,43,44,45] |

| Sutherlandia frutescens (L.) R.Br. | Fabaceae | Cancer bush | Stomach ailments, backache, diabetes, stress, fever, and wounds, HIV management. | [17,46] |

| Artemisia afra Jacq. ex Willd. | Asteraceae | African wormwood | Anthelmintic, anti-inflammatory. Anti-plasmodial, useful for coughs, colds, and fever. | [32,47,48] |

| Hypoxis hemerocallidea Fisch., C.A.Mey. & Avé-Lall. | Hypoxidaceae | African potato | Common cold, flu, hypertension, adult-onset diabetes, psoriasis, urinary infections, testicular tumors, prostate hypertrophy. | [17,32,49] |

| Helichrysum odoratissimum (L.) Sweet. | Asteraceae | Everlasting (imphepho) | Insomnia, menstrual pain and sterility, wounds and respiratory problems, intestinal worms, pain, skin infections, stomach problems, and toothache, anti-oxidant, cytotoxic activity towards cancer cells, colonic cleanser, fever symptoms. | [50,51,52,53] |

| Hoodia gordonii (Masson) Sweet ex Decne. | Apocynaceae | Milkweed, Bushman’s hat, Kalahari cactus | Appetite-suppressant. | [54,55] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nwafor, I.; Nwafor, C.; Manduna, I. Constraints to Cultivation of Medicinal Plants by Smallholder Farmers in South Africa. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7120531

Nwafor I, Nwafor C, Manduna I. Constraints to Cultivation of Medicinal Plants by Smallholder Farmers in South Africa. Horticulturae. 2021; 7(12):531. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7120531

Chicago/Turabian StyleNwafor, Ifeoma, Christopher Nwafor, and Idah Manduna. 2021. "Constraints to Cultivation of Medicinal Plants by Smallholder Farmers in South Africa" Horticulturae 7, no. 12: 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7120531

APA StyleNwafor, I., Nwafor, C., & Manduna, I. (2021). Constraints to Cultivation of Medicinal Plants by Smallholder Farmers in South Africa. Horticulturae, 7(12), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7120531