Study on the Mechanism of Resistance of Pepper Cultivars Against Phytophthora Blight via Transcriptome Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultivation of Peppers and Infection by P. capsici

2.2. RNA Preparation and Transcriptome Sequencing

2.3. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.4. Primer Design, qRT-PCR, and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Screening of Pepper Cultivars

3.2. RNA-Seq Analysis

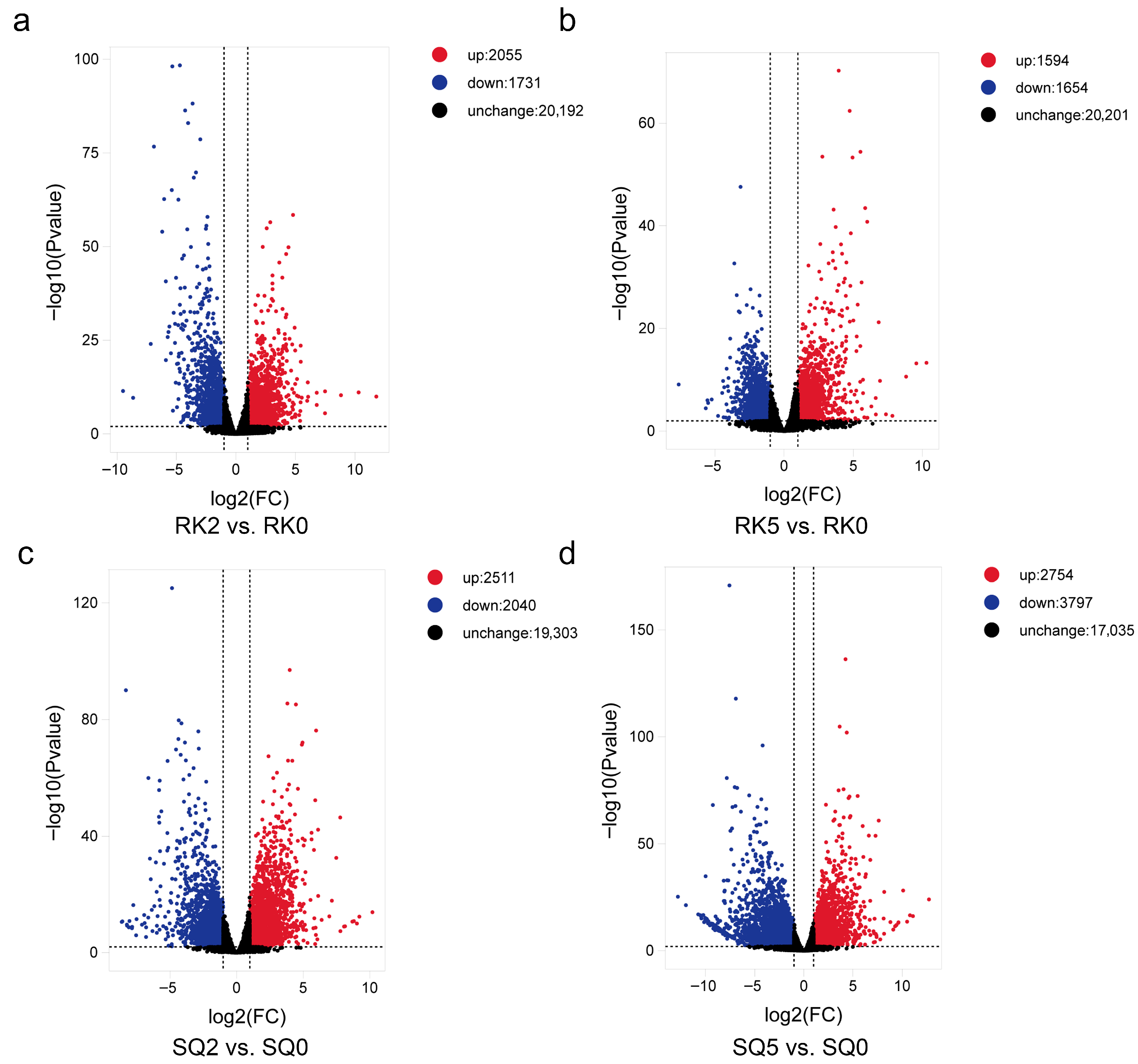

3.3. DEG Analysis

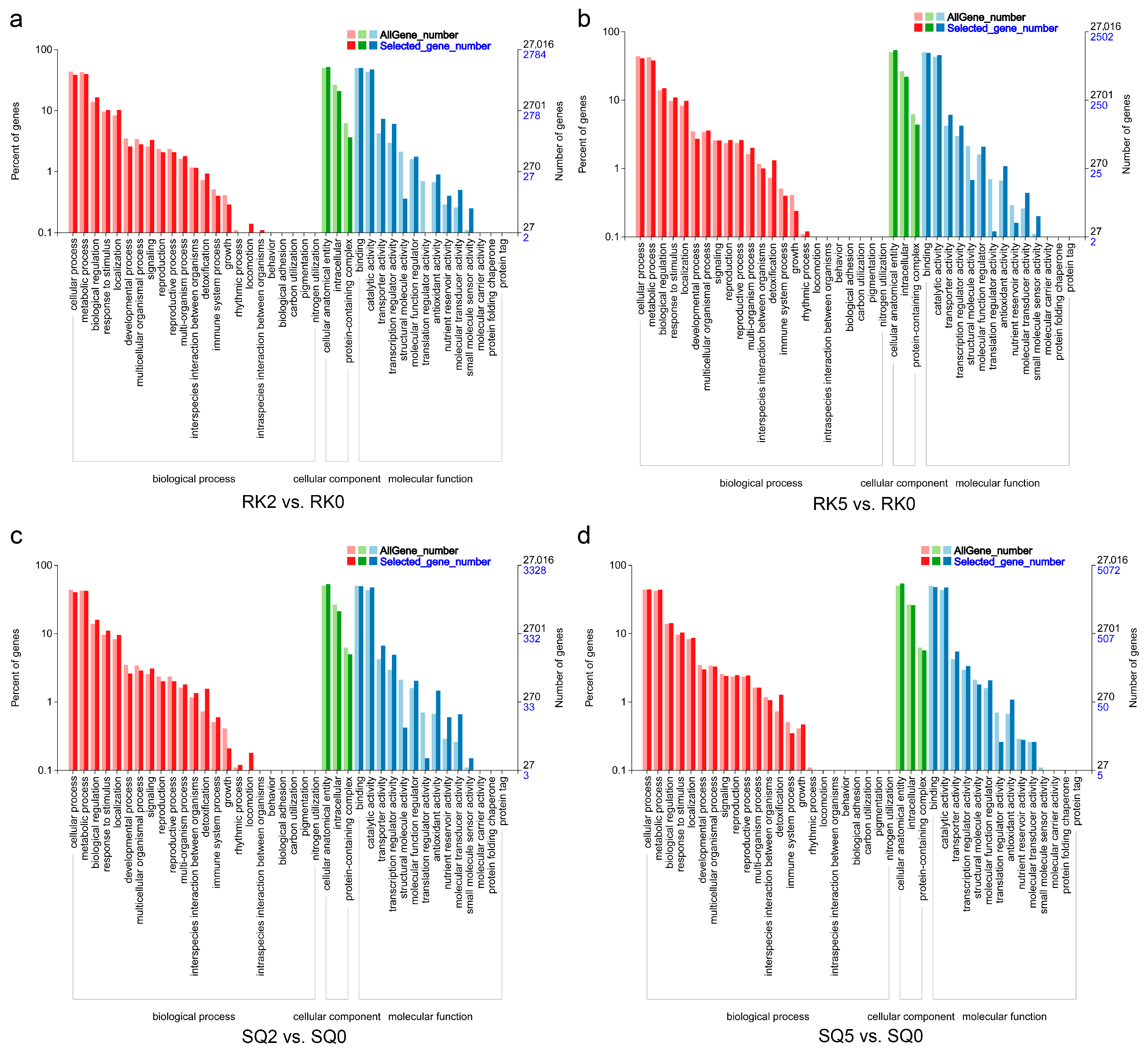

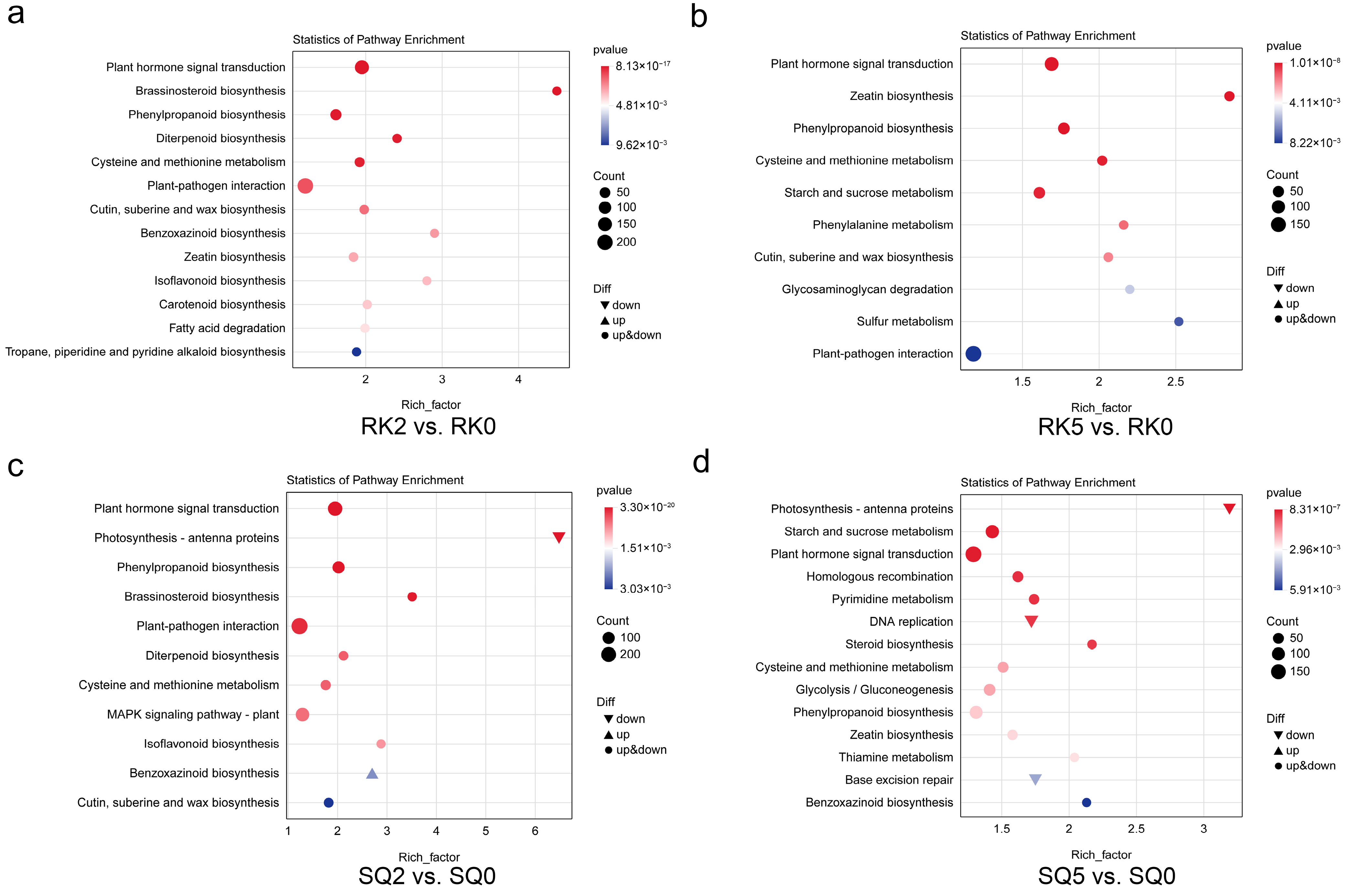

3.4. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis

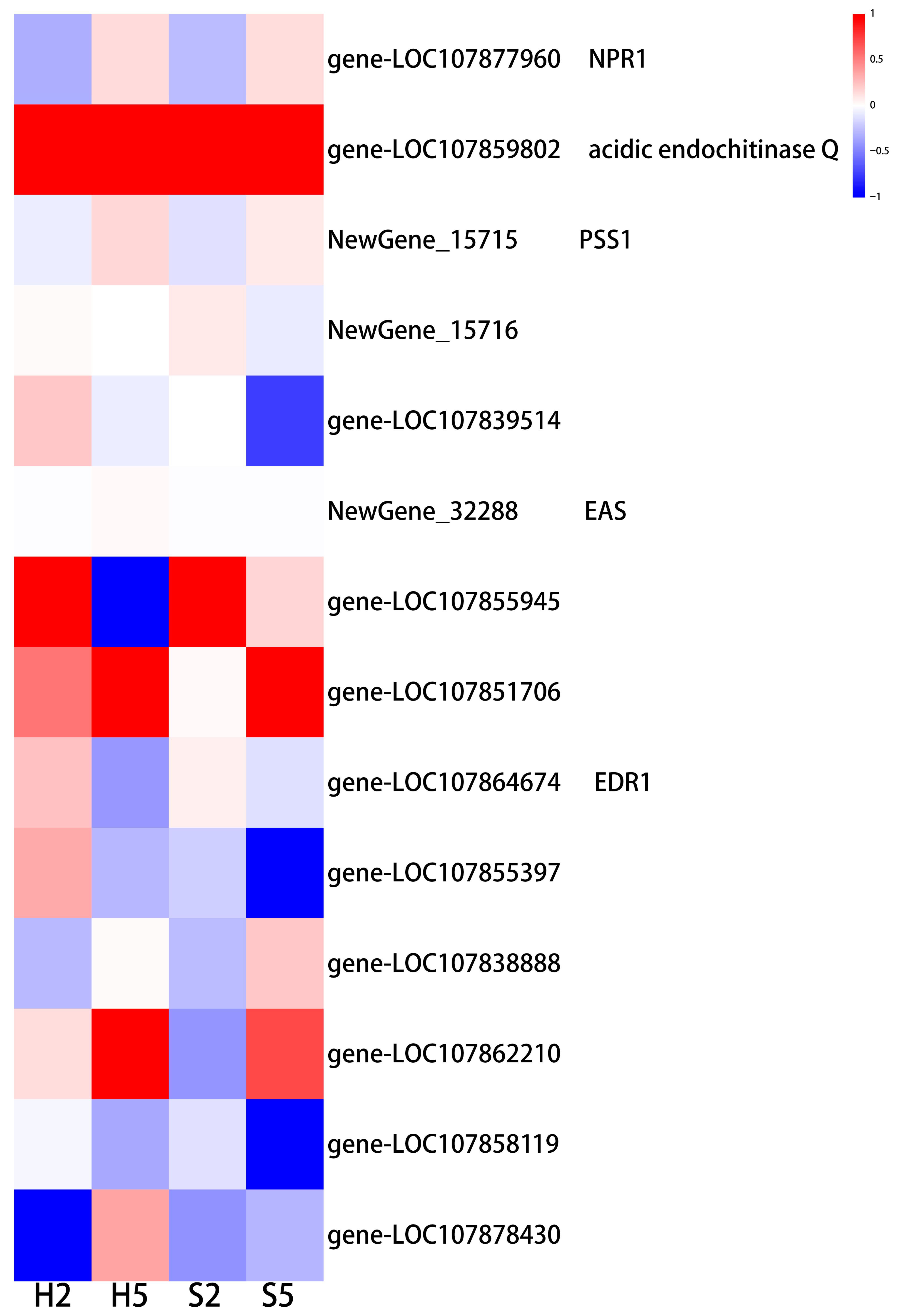

3.5. Different DEGs Between the Two Cultivars

3.5.1. Photosynthesis

3.5.2. Signal Transduction

3.5.3. Secondary Metabolism

3.5.4. Lipid Metabolism

3.5.5. Cell Wall Synthesis and Structure

3.5.6. Stress Response

3.6. qRT-PCR Analysis of Gene Expression Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, K.; Yu, H. Transposon proliferation drives genome architecture and regulatory evolution in wild and domesticated peppers. Nat. Plants 2025, 11, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Zou, X. Geographical and Ecological Differences in Pepper Cultivation and Consumption in China. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 718517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Qu, Z. Trichoderma brevicompactum 6311: Prevention and Control of Phytophthora capsici and Its Growth-Promoting Effect. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yang, F.; Yu, T.; Han, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Cryptochromes (CRYs) in pepper: Genome-wide identification, evolution and functional analysis of the negative role of CaCRY1 under Phytophthora capsici infection. Plant Sci. 2025, 355, 112460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Ocampo, L.M.; Parada-Rojas, C.H.; Hansen, Z.; Vogel, G.; Smart, C.; Hausbeck, M.K.; Carmo, R.M.; Huitema, E.; Naegele, R.P.; Kousik, C.S.; et al. Phytophthora capsici: Recent Progress on Fundamental Biology and Disease Management 100 Years After Its Description. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2023, 61, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamour, K.H.; Mudge, J.; Gobena, D.; Hurtado-Gonzales, O.P.; Schmutz, J.; Kuo, A.; Miller, N.A.; Rice, B.J.; Raffaele, S.; Cano, L.M.; et al. Genome sequencing and mapping reveal loss of heterozygosity as a mechanism for rapid adaptation in the vegetable pathogen Phytophthora capsici. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2012, 25, 1350–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamour, K.H.; Stam, R.; Jupe, J.; Huitema, E. The oomycete broad-host-range pathogen Phytophthora capsici. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, W. The Effects of Antofine on the Morphological and Physiological Characteristics of Phytophthora capsici. Molecules 2024, 29, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacey, R.F.; Fairhurst, M.J.; Daley, K.J.; Ngata-Aerengamate, T.A.; Patterson, H.R.; Patrick, W.M. Assessing the effectiveness of oxathiapiprolin toward Phytophthora agathidicida, the causal agent of kauri dieback disease. FEMS Microbes 2021, 2, xtab016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Mansfeld, B.N.; Tang, X.; Colle, M.; Chen, F.; Weng, Y.; Fei, Z.; Grumet, R. Identification of QTL associated with resistance to Phytophthora fruit rot in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1281755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Krasnow, C.S. Characterizing the Dynamics of Virulence and Fungicide Resistance of Phytophthora capsici in Michigan Vegetable Fields Reveals Loci Associated with Virulence. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Palacios, F.J.; Wang, D.; Reese, F.; Diekhans, M.; Carbonell-Sala, S.; Williams, B.; Loveland, J.E.; De María, M.; Adams, M.S.; Balderrama-Gutierrez, G.; et al. Systematic assessment of long-read RNA-seq methods for transcript identification and quantification. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 1349–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reixachs-Solé, M.; Eyras, E. Uncovering the impacts of alternative splicing on the proteome with current omics techniques. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2022, 13, e1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Kutschera, E.; Adams, J.I.; Kadash-Edmondson, K.E.; Xing, Y. rMATS-turbo: An efficient and flexible computational tool for alternative splicing analysis of large-scale RNA-seq data. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 1083–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath, P.P.; Bidaramali, V.; Lata, S.; Yadav, R.K. Transcriptomics: Illuminating the molecular landscape of vegetable crops: A review. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 34, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C. Genome engineering for crop improvement and future agriculture. Cell 2021, 184, 1621–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Qin, K.; Crosby, K.; Ong, K.; Gentry, T.; Gu, M. Biochar reduces containerized pepper blight caused by Phytophthora capsici. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Kawashima, S.; Okuno, Y.; Hattori, M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D277–D280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Cai, T.; Olyarchuk, J.G.; Wei, L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3787–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A.R.; Smart, C.D. Interactions of Phytophthora capsici with Resistant and Susceptible Pepper Roots and Stems. Phytopathology 2015, 105, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, G.; Ahl, P.; Moyer, M.; Harper, A.; Beck, J.; Meins, F., Jr.; Ryals, J. Isolation of complementary DNA clones encoding pathogenesis-related proteins P and Q, two acidic chitinases from tobacco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlumbaum, A.; Mauch, F.; Vögeli, U.; Boller, T. Plant chitinases are potent inhibitors of fungal growth. Nature 1986, 324, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Meng, Q.; Zeng, H.; Wang, W.; Yin, H. Chitosan oligosaccharide induces resistance to Tobacco mosaic virus in Arabidopsis via the salicylic acid-mediated signalling pathway. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechtold, U.; Karpinski, S.; Mullineaux, P.M. The influence of the light environment and photosynthesis on oxidative signalling responses in plant-biotrophic pathogen interactions. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 28, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, K.; Fofana, B. An Overview of Plant Photosynthesis Modulation by Pathogen Attacks. Adv. Photosynt Fundam. Asp. 2012, 22, 466–484. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Han, S.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Yang, L.; Ma, D.; Fang, Z.; Yin, J.; Zhu, Y.; Gong, S. Double roles of light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b binding protein TaLhc2 in wheat stress tolerance and photosynthesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Hou, L.; Xiao, P.; Guo, Y.; Deyholos, M.K.; Liu, X. VvWRKY30, a grape WRKY transcription factor, plays a positive regulatory role under salinity stress. Plant Sci. 2019, 280, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, H.M.; Kazan, K.; Mitter, N.; Goulter, K.C.; Birch, R.G.; Manners, J.M. Constitutive expression of a phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene from Stylosanthes humilis in transgenic tobacco leads to enhanced disease resistance but impaired plant growth. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2002, 60, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, M.; Hatan, E.; Kumar, V.; Galsurker, O.; Nisim-Levi, A.; Ovadia, R.; Galili, G.; Lewinsohn, E.; Elad, Y.; Alkan, N.; et al. Increased phenylalanine levels in plant leaves reduces susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea. Plant Sci. 2020, 290, 110289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, M.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, H.; Ge, Y. Activation of the calcium signaling, mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade and phenylpropane metabolism contributes to the induction of disease resistance in pear fruit upon phenylalanine treatment. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 210, 112782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Ali, A.; Yun, D.-J. Arabidopsis NHX Transporters: Sodium and Potassium Antiport Mythology and Sequestration During Ionic Stress. J. Plant Biol. 2018, 61, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Ji, J.; Jin, C.; Wu, G.; Guan, C. Na+/H+ antiporter (NHX1) positively enhances cadmium (Cd) resistance and decreases Cd accumulation in tobacco plants cultivated in Cd-containing soil. Plant Soil 2020, 453, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvar, C.; Merino, F.; Díaz, J. Differential activation of defense-related genes in susceptible and resistant pepper cultivars infected with Phytophthora capsici. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, M.U.; Awan, M.F.; Fatima, K.; Tahir, M.S.; Ali, Q.; Rashid, B.; Rao, A.Q.; Nasir, I.A.; Husnain, T. Genetic resources of chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) against Phytophthora capsici and their induction through various biotic and abiotic factors. Cytol. Genet. 2017, 51, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naves, E.R.; de Ávila Silva, L.; Sulpice, R.; Araújo, W.L.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Peres, L.E.P.; Zsögön, A. Capsaicinoids: Pungency beyond Capsicum. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauen, J.; Tripodi, P.; Wendenburg, R.; Tringovska, I.; Nakar, A.N.; Stoeva, V.; Pasev, G.; Klemmer, A.; Todorova, V.; Bulut, M.; et al. The genetic architecture of the pepper metabolome provides insights into the regulation of capsianoside biosynthesis. bioRxiv 2023. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Torres Zabala, M.; Littlejohn, G.; Jayaraman, S.; Studholme, D.; Bailey, T.; Lawson, T.; Tillich, M.; Licht, D.; Bölter, B.; Delfino, L.; et al. Chloroplasts play a central role in plant defence and are targeted by pathogen effectors. Nat. Plants 2015, 1, 15074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, Q.; Wang, B.; Ma, A.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Q.; Shen, B.; Hamaila, H.; Tang, T.; Qi, X.; et al. Jujube metabolome selection determined the edible properties acquired during domestication. Plant J. 2022, 109, 1116–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultivar | Disease Incidence (%) | Disease Index (%) | Resistance Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| QM | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 98.89 ± 1.36 | S |

| 21QL701 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 98.89 ± 1.36 | S |

| 19K2 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 89.72 ± 0.00 | S |

| 20cch | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 83.00 ± 8.11 | S |

| 19K5 | 97.92 ± 4.17 | 81.07 ± 8.50 | S |

| Zunla-1 | 94.44 ± 10.09 | 73.06 ± 10.19 | S |

| 18A237 | 95.83 ± 4.56 | 68.61 ± 5.31 | S |

| 19K11 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 64.44 ± 5.13 | S |

| GMLJ-2022 | 98.61 ± 3.40 | 59.44 ± 7.35 | S |

| 22-20 | 68.89 ± 19.77 | 55.50 ± 18.92 | S |

| NKLJ-2022 | 54.17 ± 24.01 | 37.22 ± 23.68 | MR |

| SF-J | 37.50 ± 26.22 | 26.67 ± 19.52 | R |

| 2SG-A | 40.28 ± 26.04 | 19.17 ± 17.91 | R |

| prennial | 19.44 ± 15.52 | 14.44 ± 12.10 | R |

| 22-29 | 18.06 ± 8.19 | 9.72 ± 3.40 | HR |

| 22-14 | 12.50 ± 11.49 | 8.06 ± 6.70 | HR |

| 22-31 | 11.11 ± 8.61 | 6.94 ± 4.52 | HR |

| SW-3-1 | 4.17 ± 6.97 | 4.17 ± 6.97 | HR |

| 20-07 | 5.56 ± 6.80 | 3.61 ± 4.76 | HR |

| 21QL703 | 1.39 ± 3.40 | 1.11 ± 2.72 | HR |

| 19K23 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | HR |

| Sample ID | Total Reads | Clean Reads | GC (%) | Q20 (%) | Q30 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RK0-1 | 47,764,412 | 23,882,206 | 42.5 | 98.24 | 95.12 |

| RK0-2 | 39,242,786 | 19,621,393 | 42.96 | 98.17 | 94.75 |

| RK0-3 | 44,654,506 | 22,327,253 | 42.91 | 98.09 | 94.77 |

| RK2-1 | 44,271,750 | 22,135,875 | 42.83 | 98.55 | 95.81 |

| RK2-2 | 46,285,946 | 23,142,973 | 42.88 | 98.4 | 95.46 |

| RK2-3 | 43,606,234 | 21,803,117 | 43.91 | 98.48 | 95.67 |

| RK5-1 | 43,603,656 | 21,801,828 | 43.01 | 98.32 | 95.17 |

| RK5-2 | 41,935,130 | 20,967,565 | 42.99 | 98.54 | 95.74 |

| RK5-3 | 41,871,816 | 20,935,908 | 42.73 | 98.46 | 95.51 |

| SQM0-1 | 42,038,314 | 21,019,157 | 42.84 | 98.4 | 95.4 |

| SQM0-2 | 51,272,556 | 25,636,278 | 43.21 | 98.18 | 95.02 |

| SQM0-3 | 42,490,384 | 21,245,192 | 43.1 | 98.2 | 94.82 |

| SQM2-1 | 39,965,446 | 19,982,723 | 42.81 | 98.51 | 95.64 |

| SQM2-2 | 45,366,038 | 22,683,019 | 42.75 | 98.38 | 95.29 |

| SQM2-3 | 44,715,138 | 22,357,569 | 42.81 | 98.39 | 95.41 |

| SQM5-1 | 54,936,376 | 27,468,188 | 49.78 | 98.04 | 94.53 |

| SQM5-2 | 50,504,238 | 25,252,119 | 47.4 | 98.19 | 94.88 |

| SQM5-3 | 62,991,546 | 31,495,773 | 48.41 | 98.15 | 94.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Zhou, B.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, Z. Study on the Mechanism of Resistance of Pepper Cultivars Against Phytophthora Blight via Transcriptome Analysis. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121458

Chen Y, Zhang Y, Zheng J, Zhang J, Li S, Zhou B, Yu Q, Zhang Z. Study on the Mechanism of Resistance of Pepper Cultivars Against Phytophthora Blight via Transcriptome Analysis. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121458

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yanyan, Yuhan Zhang, Jingyuan Zheng, Jingwen Zhang, Sheng Li, Bo Zhou, Qilin Yu, and Zhuo Zhang. 2025. "Study on the Mechanism of Resistance of Pepper Cultivars Against Phytophthora Blight via Transcriptome Analysis" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121458

APA StyleChen, Y., Zhang, Y., Zheng, J., Zhang, J., Li, S., Zhou, B., Yu, Q., & Zhang, Z. (2025). Study on the Mechanism of Resistance of Pepper Cultivars Against Phytophthora Blight via Transcriptome Analysis. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121458