1. Introduction

The genus

Dendrobium (

Orchidaceae) encompasses a diverse group of orchids with significant ornamental and medicinal value.

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium refers to a set of

Dendrobium hybrids and varieties notable for their large, showy flowers that resemble those of the genus

Phalaenopsis. These orchids are extensively cultivated in China and other parts of Asia for their esthetic appeal and pharmacological properties. Despite their horticultural importance,

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium currently lacks a publicly available comprehensive reference genome. Currently, the genomes of several orchid species, such as

Cymbidium goeringii,

Dendrobium officinale,

Dendrobium chrysotoxum, and

Dendrobium nobile [

1,

2,

3,

4], have been sequenced. However, the genome of

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium remains unavailable, limiting molecular marker design, genetic diversity analysis, and variety identification. The substantial genomic differences among

Dendrobium species make existing reference genomes unsuitable for detailed analysis of

Phalaenopsis-type varieties, hindering gene mapping, marker development, and DNA fingerprinting—all crucial for molecular breeding and accurate variety identification.

Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP) markers were used in early genetic diversity studies of

Dendrobium, to assess genetic relationships and variation [

5,

6]. Molecular markers such as simple sequence repeats (SSRs) and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are indispensable tools in plant genetics and breeding [

7]. Insertion–deletions (InDels) represent another class of markers that offer unique advantages: they are co-dominant in inheritance, abundant across genomes, and can be easily detected through PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis [

8]. The SSR markers designed based on transcriptomes have also been applied in

Dendrobium [

9,

10]. Both SSR and InDel markers are based on PCR amplification, but InDel markers offer distinct advantages. Unlike SSR markers, InDel markers do not require the use of toxic reagents such as polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and they also shorten electrophoresis time. These features make InDel markers particularly advantageous, especially in species lacking reference genomes. They allow for high-resolution genetic mapping and genotyping without the need for advanced sequencing platforms. Furthermore, AFLP, while also a powerful marker system, requires complex and labor-intensive procedures, including the use of restriction enzymes and the generation of large, difficult-to-interpret datasets. In contrast, InDel markers offer a simpler and more straightforward approach to genotyping, providing a more efficient alternative for genetic studies in non-model species like

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium. InDel markers have been successfully utilized in other plant species for genetic linkage analysis and diversity studies [

8,

11,

12], but their development in

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium has been limited by the absence of genomic data.

The diversity analysis of

Orchidaceae plants based on different markers has demonstrated that the family exhibits a complex genetic background and high heterozygosity [

13,

14,

15,

16]. This indirectly suggests a high potential for conducting InDel marker analysis in

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium. Given these challenges and opportunities, the aim of this study was to develop and validate a robust set of InDel markers for

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium using transcriptome sequencing data. Due to the absence of a reference genome for

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium and the substantial genomic differences between species within the

Dendrobium genus, a de novo transcriptome assembly approach was employed. In contrast to reference-based assembly, which relies on a pre-existing genome for mapping reads, de novo assembly builds the transcriptome directly from sequencing data, making it particularly suitable for species lacking a reference genome. This approach has been successfully applied in similar studies, such as the development of de novo transcriptome assemblies and SSR markers in

Brassica species [

17] and the comparison of de novo vs. reference genome assembly for drought stress analysis in

Brassica genotypes [

18]. By leveraging the expressed portion of the genome (the transcriptome) from two varieties with distinct phenotypic traits, a bioinformatics pipeline and custom scripts were established to identify polymorphic InDel loci and to design primers flanking those loci. This workflow included transcriptome assembly, variant discovery, InDel filtering, primer design, and in silico specificity screening, with all steps automated through our scripts. The efficacy of these markers was then tested across a diverse panel of 24

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium varieties to assess their amplification success and polymorphism. The successful development and validation of these transcriptome-based InDel markers not only provides valuable tools for genetic diversity assessment, variety identification, and breeding programs in

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium, but also demonstrates the feasibility of applying a reproducible transcriptome-derived marker development pipeline in non-model, highly heterozygous plant species lacking a complete reference genome.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

A panel of 24 hybrid Phalaenopsis-type Dendrobium varieties was collected to validate the developed markers. To ensure the broad applicability and high discriminatory power of the markers, these varieties were specifically selected based on their diverse pedigrees, representing parents from different genetic origins. These varieties include both local varieties and commercial cultivars primarily sourced from Southeast Asia and southern China, covering a wide range of phenotypic traits. The varieties included: Nopporn Green Star, Red Bull, Burana Emerald, Pop Eye, Burana White, Siri Gem, Burana Charming, Dendrobium Sripratum Delight, Swirl, Suriya Gold, Smile, Thongchai Gold, Enobi Purple, Leong Yok Kin, Asian Pearl, Caesar, Serene Chang ‘red’, Little Girl, Sonia Hiasakul, Pensuda, Rasa Saying, Burana Gold, Burbank Queen × Dal’s Jazz, Alice’s Stewart. Young leaves were collected from each variety for DNA extraction. Among these, two varieties—Sonia Hiasakul and Dendrobium Sripratum Delight—exhibit distinct phenotypic differences and were selected for transcriptome sequencing to discover polymorphic loci. The characteristics of Sonia Hiasakul include rhombic tepals with a flower color in the red-purple N79B shade, and the plant exhibits a spreading leaf habit. In contrast, the features of Dendrobium Sripratum Delight are tepals that are more ovoid in shape, with a flower color in the deep purple-red N80A shade, and the plant has a compact and erect leaf habit.

2.2. Transcriptome Data Acquisition and Analysis

To extract InDel variations and design molecular markers, Sonia Hiasakul and Dendrobium Sripratum Delight were selected as the varieties for transcriptome sequencing. Three biological replicates were selected for each parent, with the three most mature leaves from the top of each individual plant’s uppermost leaf cluster used as experimental replicates. Total RNA was extracted from young leaf tissue of the two selected varieties using the RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China), followed by RNase-free DNase I treatment (Takara Bio, Dalian, China) to remove contaminating genomic DNA. RNA quality and integrity were assessed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). High-quality RNA samples were subjected to polyA selection to enrich for mRNA, followed by the construction of complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries with the NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), generating 150 bp paired-end reads for high coverage transcriptome data.

To assess the quality of the transcriptome data, several key metrics were evaluated. Raw and clean reads were assessed using FastQC (

https://github.com/s-andrews/FastQC) (accessed on 1 March 2025), and sequencing depth was quantified by reporting the total number of raw and clean bases, as well as the Q20 and Q30 scores. Adapter sequences and low-quality bases were trimmed using Trimmomatic [

19] with appropriate parameters to ensure high-quality clean reads, including ILLUMINACLIP (2:30:10 for adapter removal), LEADING and TRAILING (for quality score < 3 trimming), SLIDINGWINDOW (size: 4, quality: 15), and MINLEN (36 bp). The assembly of the transcriptome was conducted using Trinity assembler [

20], and to reduce redundancy, the longest transcript for each gene was extracted as the representative unigene sequence. Using BUSCO v6.0.0 [

21] with the embryophyta_odb10 lineage dataset, we assessed the presence of conserved, single-copy orthologs across the assembly. The BUSCO completeness score provides an estimate of the percentage of genes in the assembly that are complete, fragmented, or missing. In this study, we also compared the Trinity assembly, which includes all isoforms, with the Unigene set, which retains only the longest transcript for each gene. This comparison allowed us to evaluate the impact of redundancy on the assembly and its downstream analysis. Trinity was run with default parameters, and the resulting contigs (transcript sequences) were clustered to produce a set of unigenes (unique representative transcripts per gene locus). The longest transcript for each gene was extracted as the representative unigene sequence (output as a unigene.fasta file).

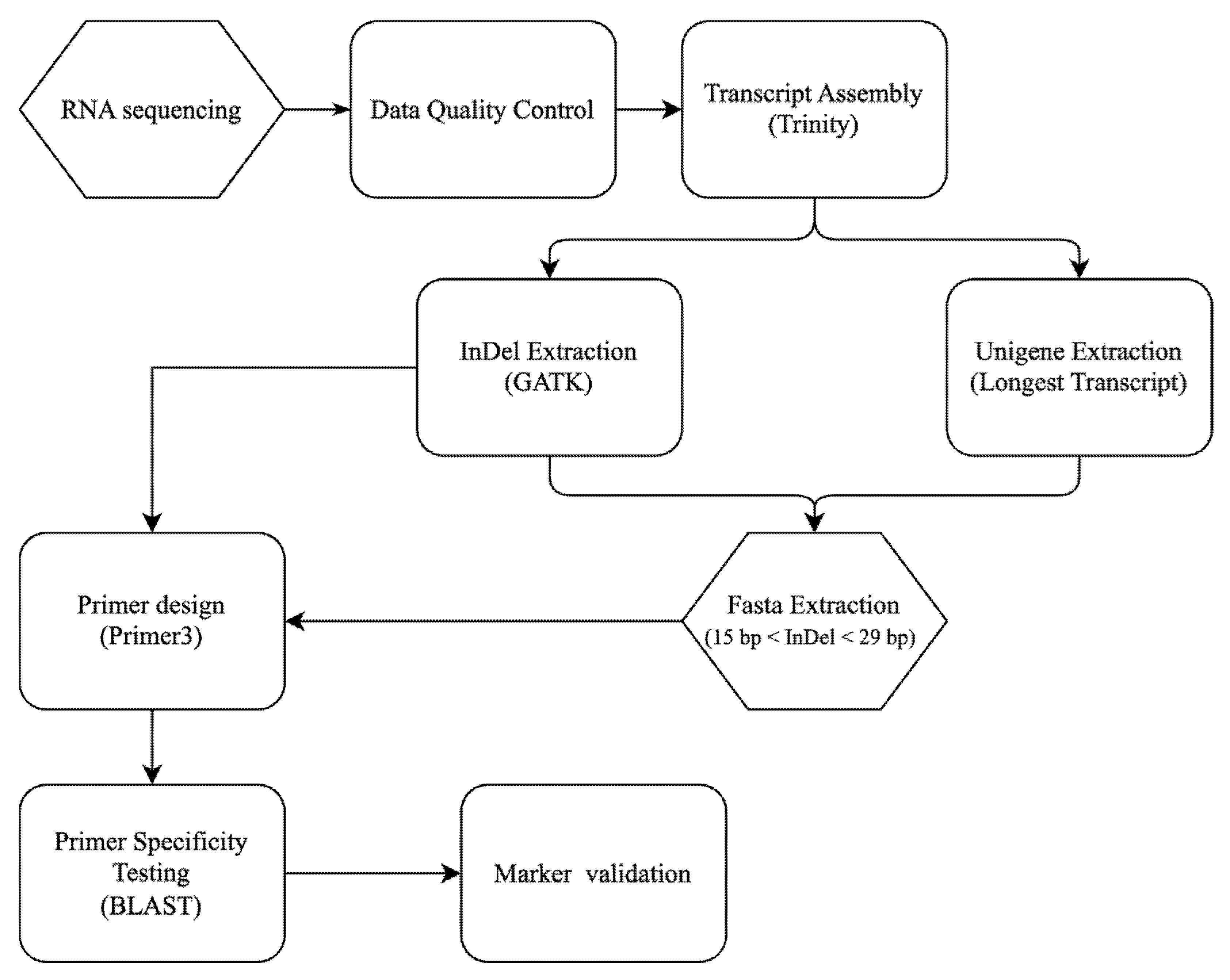

2.3. InDel Detection and Primer Design

For the identification of insertion–deletion polymorphisms, the clean RNA-seq reads from two varieties were aligned back to the assembled unigene set. Alignment was performed using a short-read aligner (BWA), treating the assembled unigenes as a pseudo-reference. The alignment files were processed with SAMtools [

22] and Picard tools to sort by coordinate, remove duplicate reads, and prepare the data for variant calling. InDel variant calling was conducted using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK v3) [

23] in UnifiedGenotyper or HaplotypeCaller mode, with parameters tuned for discovering small insertions and deletions in a pooled sample of two varieties.

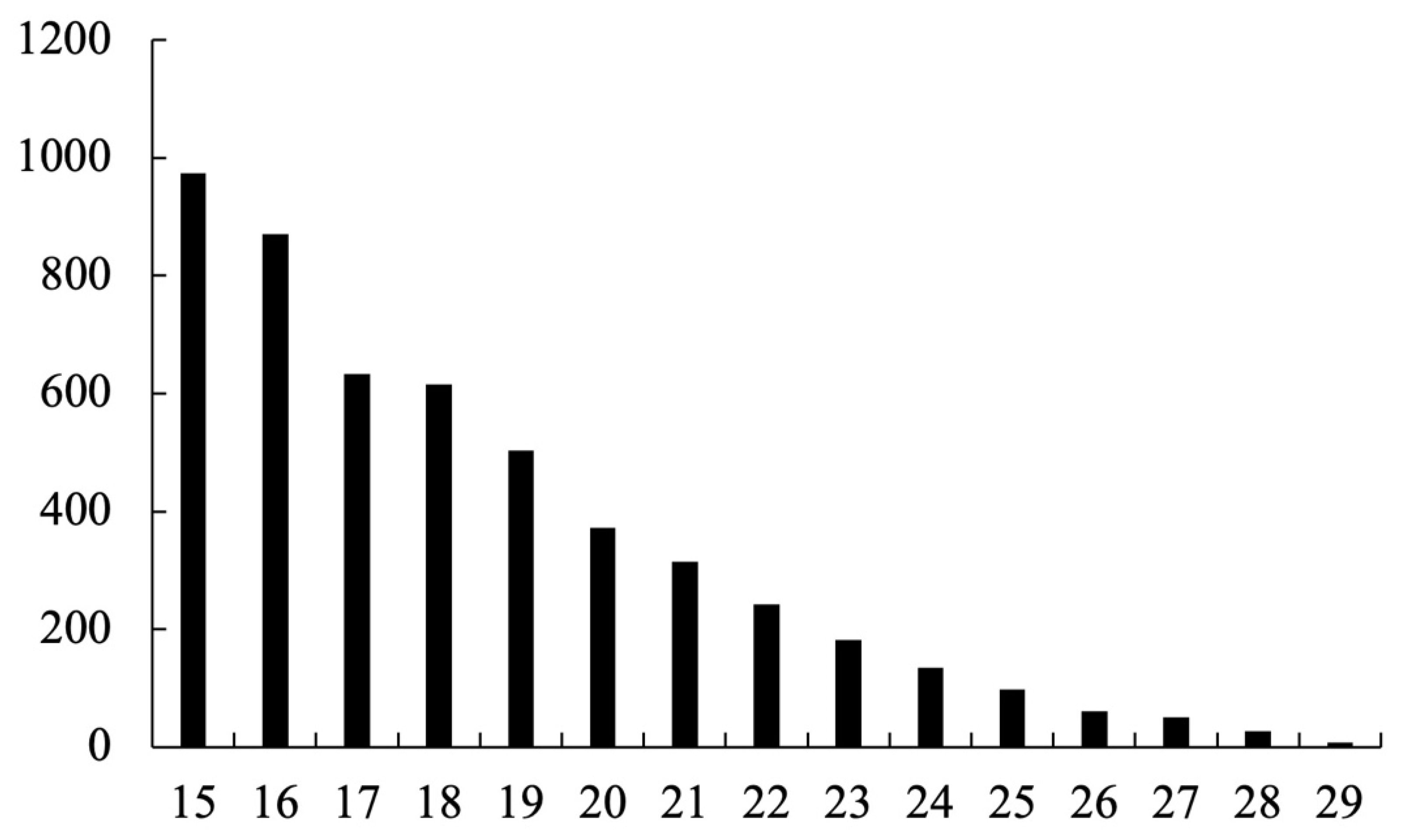

Given the highly heterozygous nature of Phalaenopsis-type Dendrobium, each genomic locus can present multiple alleles. To focus on clear bi-allelic polymorphisms and simplify downstream analysis, the raw InDel calls were filtered with the following criteria: (1) retain only loci with up to two alternate alleles (any site with more than two allelic variants across the two varieties was excluded), and (2) require an indel length difference between reference and alternate allele of 15–29 bp. InDel loci not meeting these criteria were discarded. After filtering, the coordinates of the remaining InDels (relative to the unigene sequences) were used to extract the corresponding sequences from the unigene.fasta file for primer design. This extraction was automated with a custom Python (version 3.12.4) script (step1.extract_indel.py).

For each high-confidence InDel locus, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers flanking the indel region were designed. To ensure the primers would amplify a product spanning the indel, a 300 bp sequence window centered on each InDel (approximately 150 bp upstream and 150 bp downstream of the indel site) was extracted using another script (step2.150bp.py). This sequence window served as the template for primer design. Primer3 was employed [

24] to design up to five primer pairs for each InDel locus, targeting an amplicon size of 260–280 bp that includes the indel. Primer design criteria were primer length 20–24 nucleotides, melting temperature (Tm) 56–60 °C (optimized around 58 °C), and GC content 40–60%. These parameters were chosen to ensure robust PCR performance and similar annealing temperatures across primers. This automated design process was implemented via a script (step3.primerdesign.py), generating a list of candidate primer pairs for each InDel.

The primer sequences generated for all candidate InDel markers were compiled and converted into FASTA format (step4.extract-primer.py) to facilitate specificity screening. To ensure that each primer pair would amplify a unique target (the intended InDel locus) and not bind elsewhere in the genome, an in silico specificity check was performed using BLAST (version 2.16.0+). Since a complete reference genome for

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium was unavailable, the draft genome sequences of

Dendrobium nobile [

25] was used, a different ecological type within the

Dendrobium genus, as a surrogate reference genome. A BLAST database was constructed from the

Dendrobium nobile genome and performed BLAST searches to assess primer specificity. Each primer sequence (forward and reverse) was searched against this genome database using NCBI BLAST+ (blastn). BLAST hits with E-value < 10

−5 were examined. If a primer had multiple significant hits or a second-best hit with comparable E-value to the best hit, it was considered non-unique. The primer pair was filtered by removing any pair where either primer showed multiple binding sites in the genome. In practice, the BLAST output for each of the five candidate primer pairs per locus sequentially was analyzed: if the top-ranked primer pair was not unique, the next primer pair for that locus was evaluated, and so on. If none of the five primer pairs for a given locus was uniquely mapped, that InDel locus was deemed unsuitable and dropped from further consideration. This filtering step (implemented with script step5.blast.py) ensured that the remaining primers likely amplify only the specific target locus. After this specificity screening, at most one primer pair per locus was retained (the first pair that passed the uniqueness criterion). Finally, the information about all retained primer pairs (InDel locus ID, primer sequences, expected amplicon size, etc.) were collated into a final primer list using a script (step6.final.py). All custom scripts used in the bioinformatic pipeline are available in our GitHub repository (version 1.0.0) (

https://github.com/biodendrobium/InDel-Marker-Design-Using-Transcriptome-Data) (accessed on 1 October 2025).

2.4. Selection of Primer Pairs for Validation

From the pool of InDel primer pairs that passed the in silico filtering (1029 specific primer pairs in total), 50 primer pairs were selected for experimental validation. The selection was done randomly while ensuring that a range of InDel sizes and loci from different unigenes were represented. These 50 primer pairs were synthesized (Beijing Tsingke Biotech, Beijing, China) and used to genotype the full panel of 24

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium varieties described above. Genomic DNA from each variety was extracted from young leaves using a modified CTAB method [

26].

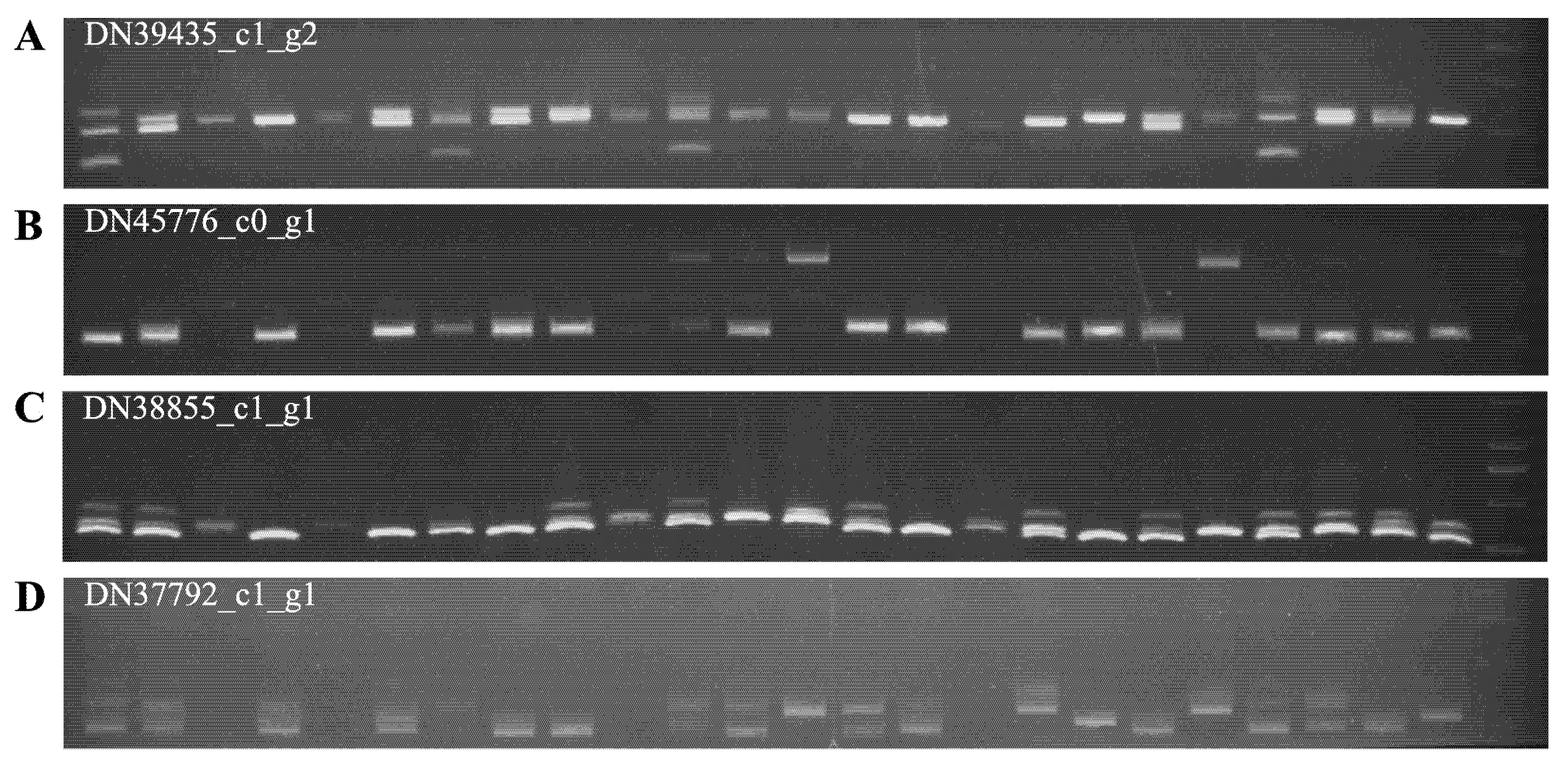

PCR amplifications were carried out in a 20 μL reaction volume containing approximately 50 ng of template genomic DNA, 0.2 μM of each primer (forward and reverse), 200 μM of each dNTP, 2 μL of 10× PCR buffer (with Mg2+), and 0.5 U of rTaq DNA polymerase (Takara Bio, Beijing, China). The PCR cycling conditions were initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, primer-specific annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 2 min. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel stained with 3% fluorescent DNA dye (GoldView, Zomanbio, Beijing, China). A 100 bp DNA ladder was run alongside to estimate fragment sizes. Gel images were visualized under UV light and documented.

For each primer pair, the presence or absence of bands was recorded for all 24 samples. Primers that produced no PCR product in all samples were noted as failures. Primers that produced a single band of the expected size in all samples were noted as non-polymorphic. Primers that yielded bands of different sizes among the varieties were considered polymorphic. Distinct genotypes were assigned codes to different banding patterns: for instance, if a marker produced a single band of a unique size in one variety and a different size band in another, these would be scored as different alleles (homozygous genotypes). If a variety showed two bands (indicating heterozygosity for two different alleles), that pattern was recorded as a separate genotype as well. Thus, each unique band size or combination of band sizes was treated as a distinct genotype for analysis.

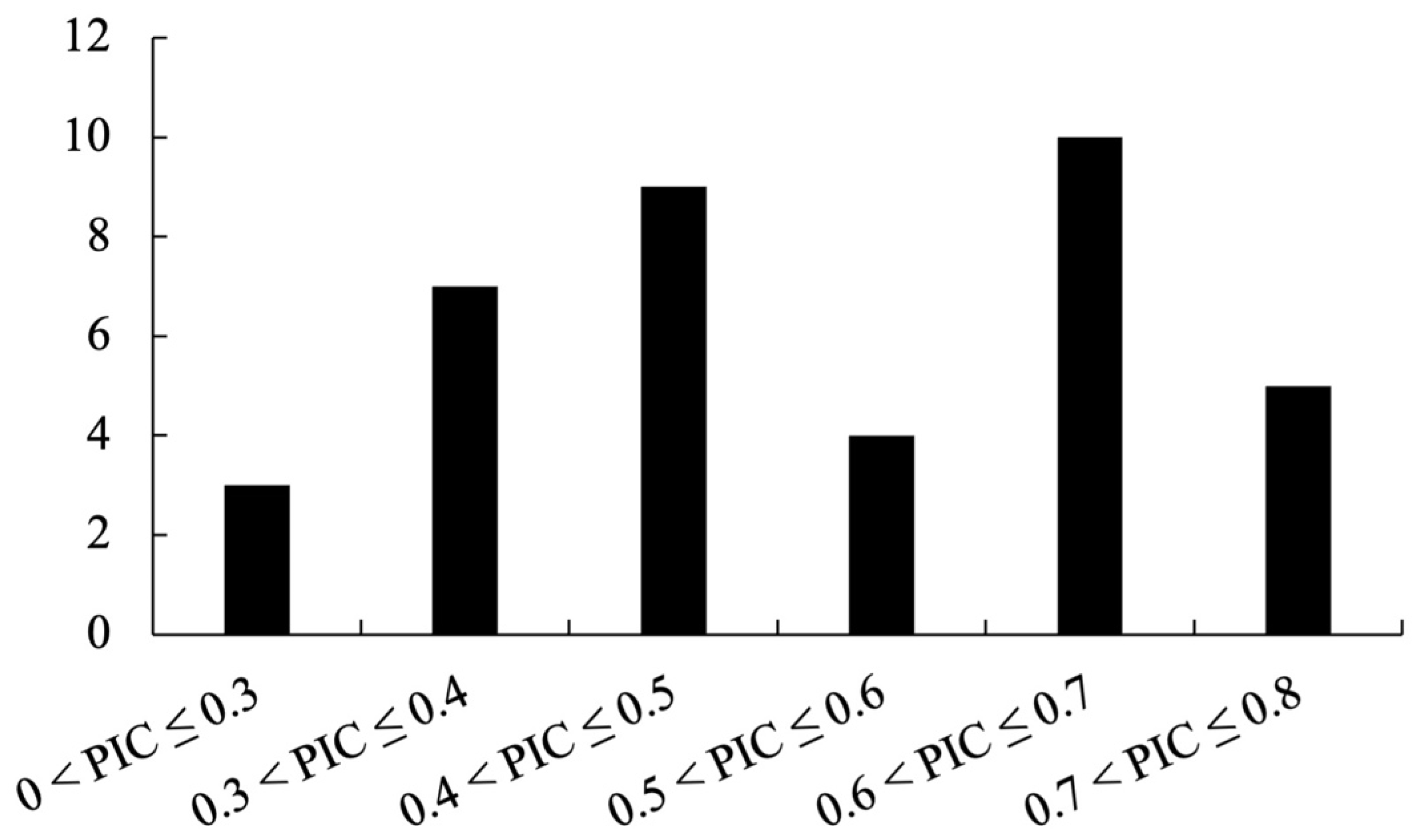

2.5. Data Analysis

The polymorphism information content (PIC) was calculated for each polymorphic marker to assess its informativeness. PIC is defined as:

where

pij is the frequency of the

j-th allele of the

i-th marker in the sample set [

11,

27]. A higher PIC value (close to 1) indicates a more informative (highly polymorphic) marker, whereas a value of 0 indicates a monomorphic marker. Frequencies were calculated for each marker based on the observed banding patterns (genotypes) in the 24

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium varieties and then computed PIC values accordingly.

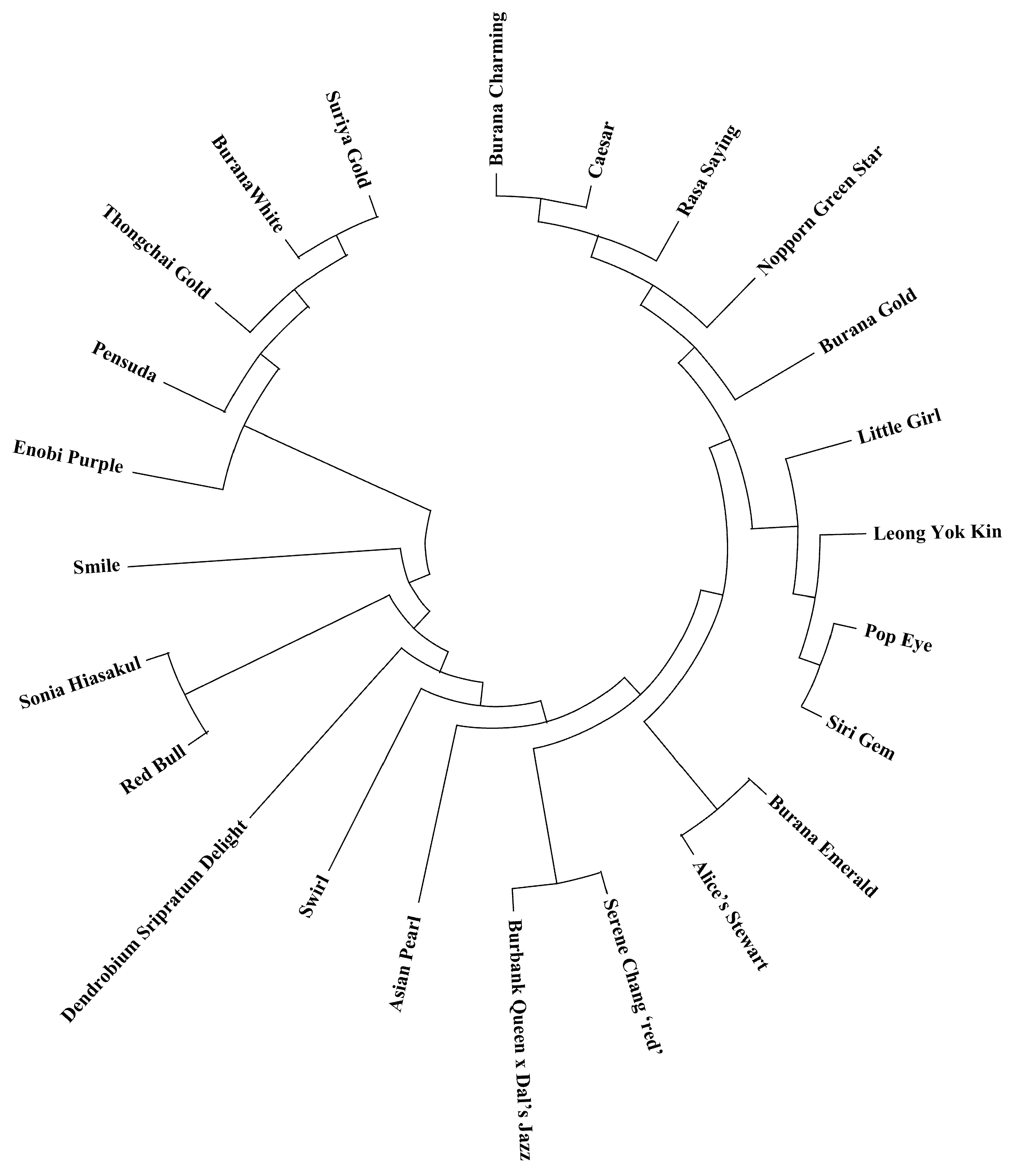

To examine genetic relationships among the 24

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium varieties, a binary genotype matrix from the gel analysis of the polymorphic markers (scoring each variety for presence/absence of each allele at each locus) was compiled. Using this data, a pairwise genetic similarity matrix was calculated based on Jaccard’s coefficient [

28], which considers the proportion of shared alleles between each pair of varieties. Genetic distance and distance matrix was analyzed using the NTSYSpc software [

29] to perform cluster analysis. A dendrogram was constructed using the UPGMA method, a widely used distance-based clustering algorithm, to visualize the genetic relationships. The robustness of clustering was visually assessed, and the dendrogram was drawn using MEGA X [

30].

4. Discussion

In this study, a new set of polymorphic InDel markers for Phalaenopsis-type Dendrobium was successfully developed and validated using a transcriptome-driven approach. The challenges posed by the absence of a complete reference genome and the highly heterozygous nature of Phalaenopsis-type Dendrobium were effectively addressed by focusing on expressed gene regions and applying stringent selection criteria for marker development. By sequencing the transcriptomes of two phenotypically distinct varieties and comparing their assembled sequences, nearly 174,000 raw InDel candidates were identified. The filtering steps (limiting to bi-allelic indels of moderate size 15–29 bp) reduced this to a manageable set of 5000 high-confidence loci. This strategy enabled us to target indels that are likely to produce clear, distinguishable differences on agarose gels and to avoid complex indels that might be difficult to genotype or interpret. The approach of limiting alternate allele types also minimized complications from multi-allelic loci (which are common in orchids due to segmental duplications and polyploidy in some species). In essence, our workflow demonstrates how transcriptome data from just two individuals can yield a wealth of genetic markers, even in the absence of a reference genome.

The de novo transcriptome assembly provided a robust foundation for marker discovery, as evidenced by the large number of unigenes (156 k) and a substantial N50 of nearly 1.4 kb. By mining this assembly for variants between two divergent varieties, the natural genetic variation present in the Phalaenopsis-type Dendrobium gene pool was revealed. The identification of ~5083 useful indels is a testament to the genetic divergence between Sonia Hiasakul and Dendrobium Sripratum Delight—these two varieties contributed a substantial number of differences, which is not surprising given their distinct origins and traits. This also implies that other variety combinations might yield additional markers, and expanding to more transcriptomes could further enrich the marker resource for Phalaenopsis-type Dendrobium.

Transcriptome-derived variant calling can be influenced by sequence similarity among paralogous genes or alternative isoforms, which may cause ambiguous read mapping and lead to potential false-positive variants—a known limitation of RNA-seq-based polymorphism discovery. Highly similar paralogous genes or alternative splicing isoforms can generate multiple nearly identical transcripts, resulting in mapping ambiguity when short reads are aligned to these transcripts. While Trinity’s default strategy of retaining the longest transcript for each gene helps reduce redundancy, it does not fully eliminate the possibility of misalignment. The Unigene set, which retains only the longest transcript for each gene, further minimizes the impact of transcript redundancy, thus providing a more refined representation of gene content and reducing misalignment caused by paralogous genes or isoforms. However, the relatively higher M (missing) and F (fragmented) values in the Unigene assembly indicate that it has some gaps, which may lead to fewer InDel markers and lower marker coverage compared to the Trinity assembly. While Unigene offers a more accurate and precise depiction of the transcriptome, it may miss some of the genetic diversity captured by the Trinity assembly, which includes a broader range of gene isoforms and duplicated genes. To further mitigate these issues, future efforts could incorporate long-read sequencing technologies such as PacBio Iso-Seq or Oxford Nanopore, which provide full-length transcript sequences and help resolve complex regions of the genome. Additionally, clustering paralogous sequences based on similarity thresholds or applying more stringent mapping criteria could improve the accuracy of InDel detection by reducing the impact of redundancy and misalignment.

Our primer design and in silico filtering pipeline proved to be effective, yielding over a thousand candidate markers with a high likelihood of specificity. The BLAST screening against the draft

Dendrobium nobile genome [

25] was particularly crucial. Orchids are known for large and repetitive genomes; thus, cross-amplification of primers on non-target sequences is a serious concern. By removing primers that had multiple binding sites, the success rate of our markers in the lab was dramatically improved. The experimental validation results underscore this point: 84% of tested primer pairs produced a clear single band, and none of the successful amplifications showed spurious bands. This is a notably high success rate for de novo marker development. In similar studies without rigorous specificity checks, it is common to encounter a higher proportion of primers that amplify either nothing or multiple bands. Therefore, our approach can serve as a model for marker development in other species lacking reference genomes, combining transcriptome mining with genome filtration to identify reliable markers.

The polymorphism rate among the successful markers 38 out of 50 (76%) is also encouraging. It indicates that a large fraction of the transcriptome-derived indels are truly variable across the broader set of Phalaenopsis-type Dendrobium germplasm, not just between the two varieties used for discovery. Compared to widely used SSR and SNP marker systems, the transcriptome-based InDel markers developed in this study offer a distinct balance of cost-efficiency, operational simplicity, and discriminatory power. While SSR markers are known for their high polymorphism and allelic diversity, their detection often necessitates polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), a process that is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and involves the use of toxic reagents. In contrast, the InDel markers designed here are resolvable on standard agarose gels, significantly reducing the genotyping workload and eliminating safety hazards associated with PAGE. On the other hand, while SNP markers provide high genomic density and are ideal for high-throughput automated platforms, they typically incur higher development and running costs per sample and require specialized equipment (e.g., fluorescence scanners or sequencers) that may not be available in basic breeding laboratories.

In terms of discriminatory power, our InDel markers exhibited an average PIC of 0.52, which is comparable to the informativeness of many Dendrobium SSR markers reported in previous studies (typically ranging from 0.5 to 0.8) [

31]. Although SNPs and SSRs may offer higher density or allele numbers, respectively, the bi-allelic nature of InDel markers simplifies scoring and reduces genotyping errors. Furthermore, because these markers are derived from transcribed regions (CDS and UTRs), they target evolutionarily conserved sequences. This feature suggests they may possess higher cross-species transferability compared to genomic SSRs often located in rapidly evolving intergenic regions, potentially extending their utility to related

Dendrobium species.

The genetic relationships revealed by our markers provide insights into the genetic structure of

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium varieties. The relatively high genetic similarity among many varieties suggests that breeders may have used a limited core set of parent plants or that certain hybrids have been widely used in breeding, leading to a degree of relatedness among modern varieties. This is not unexpected in ornamental breeding, where a few popular hybrids can dominate lineage due to their desirable traits (e.g., large flower size or particular colors). However, the fact that clear clustering and a range of genetic distances (with some pairs of varieties being quite distinct) were still observed indicates that there is substantial genetic diversity that can be leveraged [

32]. For breeding programs, this has two implications: (1) breeders can use the markers to identify genetically divergent parents to maximize heterosis or to introduce new variation (as per the concept of optimizing parental selection for mapping populations; and (2) the existing genetic clusters might correspond to particular trait groupings, so crossing between clusters could combine complementary traits (e.g., crossing a large-flowered cluster I variety with an early-flowering cluster III variety to generate progeny with both advantages). Our results also suggest that if the breeding pool remains too narrow (high similarity), it may be beneficial to introduce new germplasm (perhaps wild

Dendrobium species or less-related hybrids) to broaden the genetic base. The markers that developed would be instrumental in monitoring the integration of such new germplasm and assessing its impact on genetic diversity [

33].

From a methodological perspective, our work demonstrates the utility of transcriptome sequencing for marker development in a non-model organism. By focusing on the transcribed portions of the genome, much of the “noise” associated with repetitive DNA that plagues whole-genome approaches in complex genomes was avoided [

34]. While the transcriptome-based approach efficiently avoids the complexity of repetitive genomic sequences, it is important to acknowledge its inherent biases. Since RNA-seq focuses exclusively on expressed regions (CDS and UTRs), genetic variations located in non-coding regulatory elements (such as promoters, introns, and enhancers) and intergenic regions are inevitably missed. Consequently, the InDel markers developed herein may underrepresent the total landscape of genetic variation, particularly in regulatory regions that drive expression differences. However, this limitation is counterbalanced by the fact that the identified markers are physically linked to functional genes. Unlike random genomic markers in intergenic spacers, these gene-targeted markers have a higher probability of being associated with phenotypic traits, making them particularly valuable for downstream applications such as marker-assisted selection and functional gene mapping. The fact that our markers are gene-based also means they could be useful for comparative studies: for example, many might amplify in related

Dendrobium species or hybrids, potentially allowing cross-transfer of these markers to germplasm outside our current set. The validation of these markers across a broader range of

Dendrobium species will be a priority in our future research to fully assess their transferability. Looking ahead, the integration of these transcriptome-derived markers with a physical map will be a critical step once a high-quality chromosome-level reference genome for

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium becomes available. Since the markers are developed from specific unigenes, their sequences can be computationally anchored to the physical chromosomes using BLAST alignment. This physical mapping will not only reveal the genomic distribution and density of the markers but also help assign them to specific linkage groups. Aligning the genetic map constructed from these InDel markers with the physical genome will bridge the gap between phenotypes and genotypes, significantly accelerating the identification of candidate genes within quantitative trait loci (QTLs) and facilitating map-based cloning for key ornamental traits. Notably, the pipeline employed—de novo assembly, variant calling, filtering, primer design, and BLAST screening—is broadly applicable and can be replicated in other species when transcriptome data from two or more individuals with relevant differences are available [

35].

In summary, the development of these InDel markers fills a significant gap for

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium. Prior to this, molecular marker studies in

Dendrobium largely relied on ISSR or AFLP techniques, or a limited number of SSR markers developed for specific species [

36]. The new markers provide a more sequence-specific and reproducible toolkit. They can be used to establish DNA fingerprints for variety protection and identity verification, which is important given the high commercial value of certain orchid hybrids. They also enable more rigorous genetic diversity assessments to guide conservation efforts for germplasm collections and breeding repositories, ensuring that the full range of genetic variation is captured and maintained. Furthermore, in a breeding context, these markers can facilitate marker-assisted selection (MAS): for instance, if certain markers are found to be linked to desirable traits (like disease resistance or particular flower characteristics), breeders can screen seedlings for those markers rather than waiting for the plants to mature and bloom [

37].

Beyond

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium, both SSR and InDel markers have shown great potential in other orchid species. For example, SSR markers have been widely used for genetic diversity studies and cultivar identification in species like

Cattleya [

38],

Dendrobium nobile [

39], and

Cymbidium [

40], providing valuable tools for germplasm conservation and breeding. Similarly, the application of InDel markers in orchids has gained momentum due to their advantages in genotyping, including simpler detection methods and higher resolution in detecting genetic variation compared to traditional markers. In species such as

Orchidaceae and

Paphiopedilum, InDel markers have been effectively employed for genetic mapping, marker-assisted selection, and breeding programs aimed at improving disease resistance, flower traits, and adaptation to environmental stresses [

41,

42]. This study, by demonstrating the utility of InDel markers in

Phalaenopsis-type

Dendrobium, lays the groundwork for extending these markers to other plants, where limited genomic resources are available [

43].

One interesting observation from our results is that even with moderate genetic diversity detected, each of the 24 varieties was uniquely identifiable by a combination of these markers (a genetic “fingerprint”). This is crucial for variety registration and protection. It also implies that the number of markers can be further reduced to a core set for routine identification—for example, a panel of the top 10 most polymorphic InDel markers might suffice to distinguish all 24 varieties in our test (since none were identical across all those loci) [

44]. More varieties were added to the analysis because the panel might need to grow, but with 1029 markers available in our library, there was ample room to create high-discriminatory panels.

The approaches and findings here provide a framework for other non-model, highly heterozygous crops. Ornamental plants, many fruit trees, and medicinal herbs often lack reference genomes, yet with decreasing costs of RNA sequencing, the transcriptome-to-marker route is very feasible [

45]. This study serves as a case example showing that high-throughput sequencing data can be translated into practical breeding tools even in the absence of complete genome information.