Advances and Perspectives in Comprehensive Assessment of Medicinal–Ornamental Multifunctional Plants

Abstract

1. Introduction

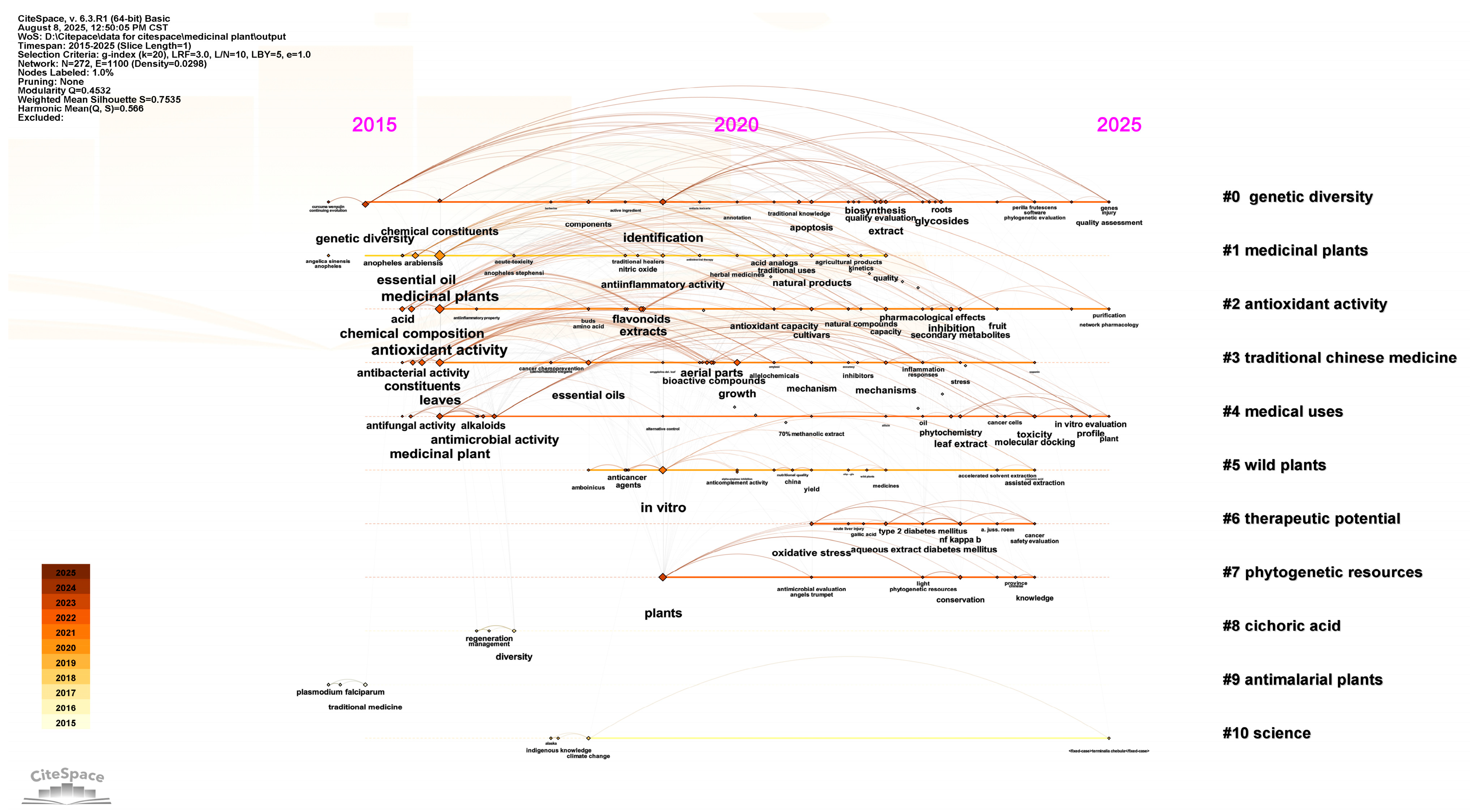

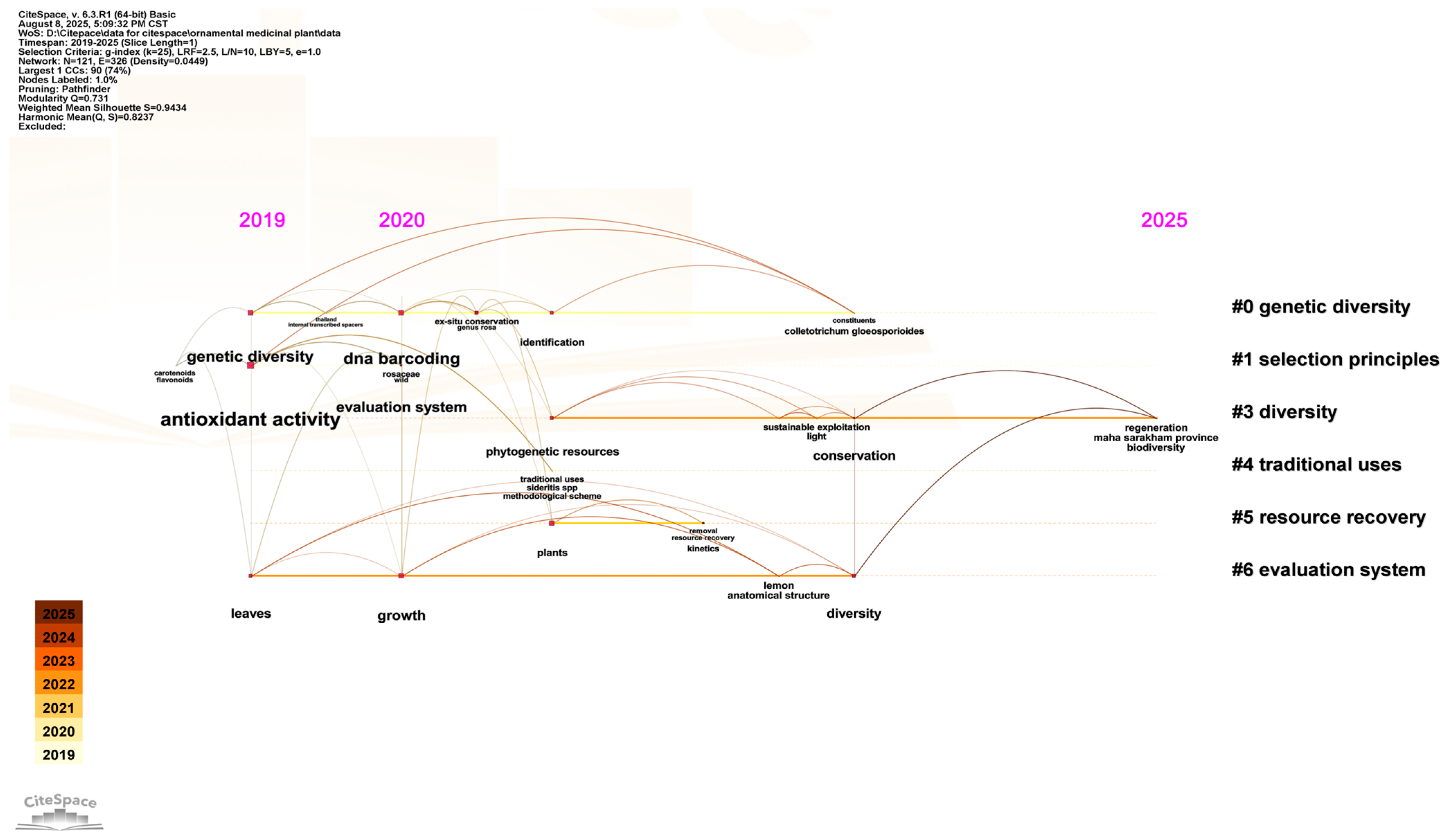

2. Comparative Analysis of Studies on Medicinal, Ornamental, and Medicinal–Ornamental Plant Resource Evaluation

3. The Importance of Resource Evaluation for Medicinal–Ornamental Multifunctional Plants

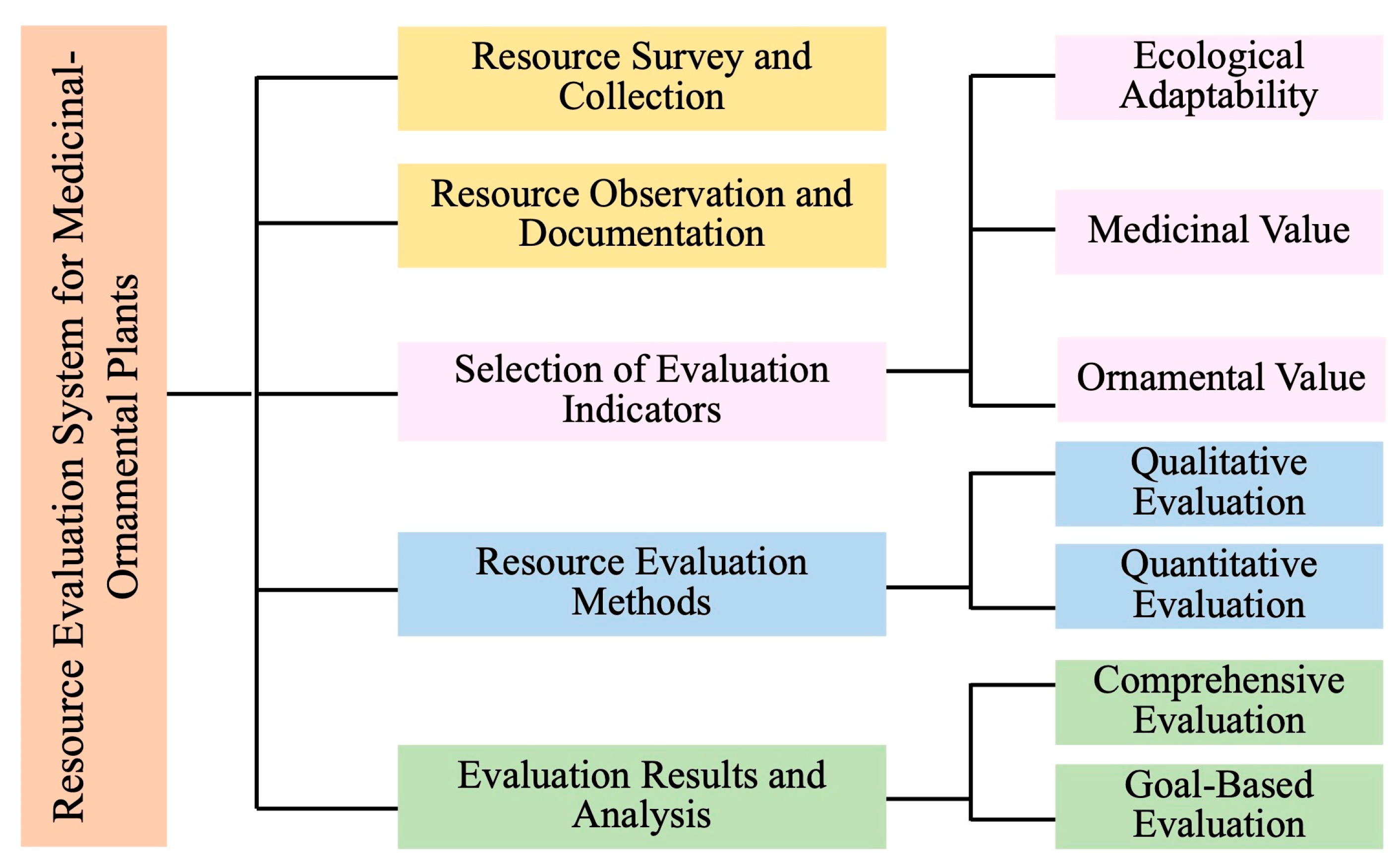

4. Construction of a Comprehensive Evaluation System for Medicinal–Ornamental Plant Resources

4.1. Evaluation of Resources

4.1.1. Ecological Adaptability

- (1)

- Growth Vigor

- (2)

- Stress Resistance

- (3)

- Propagation and Cultivation Feasibility

4.1.2. Medicinal Value

- (1)

- Application Frequency

- (2)

- Medicinal Plant Parts

- (3)

- Geoherbalism (Daodi)

- (4)

- Resource Development Potential

4.1.3. Ornamental Value

- (1)

- Plant Habit

- (2)

- Flower, Leaf, and Fruit Color

- (3)

- Flowering Period

- (4)

- Viewing Season

4.2. Methods for Evaluating Medicinal–Ornamental Plant Resources

4.2.1. Percentage Scoring Method

4.2.2. Analytic Hierarchy Process

4.2.3. Gray System Theory

4.2.4. Psychophysics Method

4.2.5. Experimental Statistical Method

5. Recommendations and Prospects

5.1. The Urgent Need to Establish a Comprehensive Evaluation System

5.2. Appropriately Balance Comprehensive Targeted Evaluations and Select Indicators Based on Specific Needs

5.3. Strengthening Resource Evaluation to Support Breeding

5.4. Applying New Technologies and Methods in Medicinal–Ornamental Plant Resource Evaluation

5.5. Constructing a Conceptual Framework for Comprehensive Assessment

6. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, G.; Chen, M. Evaluation of resource management in medicinal plant parks based on the analytic hierarchy process. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 36, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Wu, C.; Zhu, N.; Guo, A.; Wang, H.; Guo, L. Species of Chinese materia medica resources based on the fourth national survey of Chinese materia medica resources. Sci. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2024, 2, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Yu, H.; Luo, H.M.; Wu, Q.; Li, C.F.; Steinmetz, A. Conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants: Problems, progress, and prospects. Chin. Med. 2016, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narandžić, T.; Ružičić, S.; Grubač, M.; Pušić, M.; Ostojić, J.; Šarac, V.; Ljubojević, M. Landscaping with Fruits: Citizens’ Perceptions toward Urban Horticulture and Design of Urban Gardens. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Q.; Chen, S.; Yu, W.; Ji, W. Species Diversity and Spatial Distribution of Medicinal Ornamental Plants in Qinling-bashan Mountains Area of Shaanxi Province. Chin. Wild Plant Resour. 2024, 43, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.P.; He, H.B.; Wang, Z.X.; Wei, C.; Li, S.; Jia, G.X. Investigation and evaluation of the genus Lilium resources native to China. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2014, 61, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhao, J.L.; Pan, Y.Z.; Xu, Y.; Sun, L.X.; Liu, Q.L. Collection and evaluation of Primula species of western Sichuan in China. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2014, 61, 1245–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Meng, T.; Bi, X.; Li, J.; Wang, H. Investigation and evaluation of wild Iris resources in Liaoning Province, China. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2017, 64, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.J.; Ye, J.F.; Hao, D.C.; Xiao, P.G.; Chen, Z.D.; Lu, A.M. Distribution patterns and industry planning of commonly used traditional Chinese medicinal plants in China. Plant Divers. 2021, 44, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, Z.; Kahraman, O. Edible ornamental plants used in landscaping areas: The case of Çanakkale City Center. AgroLife Sci. J. 2022, 11, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Banijamali, S.M.; Azadi, P. Evaluating domestic Achillea millefolium as a suitable plant to use in the urban landscaping of dry and semi-dry regions. J. Med. Plants By-Prod. 2023, 12, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, M.; Ince, A.G. Conservation of Biodiversity and Genetic Resources for Sustainable Agriculture. In Innovations in Sustainable Agriculture; Farooq, M., Pisante, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, W.; Ayaz, A.; Park, S. Climate change and medicinal plant biodiversity: Conservation strategies for sustainable use and genetic resource preservation. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2025, 72, 6275–6308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Xiong, Y.J.; Wei, H.Y.; Li, Y.; Mao, L.F. Endemic medicinal plant distribution correlated with stable climate, precipitation, and cultural diversity. Plant Divers. 2022, 45, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, V.; Varghese, D.; Shaik, S. Towards long-term conservation of Siphonochilus aethiopicus, a critically endangered South African medicinal species: An improvement on micropropagation using in vitro shoot apices. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 180, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, Z.A.; Pant, S.; Bhat, J.A.; Shukla, G. Distribution and survival of medicinal and aromatic plants is threatened by the anticipated climate change. Trees For. People 2024, 16, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antraccoli, M.; Carta, A.; Astuti, G.; Franzoni, J.; Giacò, A.; Tiburtini, M.; Pinzani, L.; Peruzzi, L. A comprehensive approach to improving endemic plant species research, conservation, and popularization. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2023, 4, 490–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klymenko, H.; Artemenko, D.; Klymenko, I.; Kovalenko, N.; Melnyk, A.; Butenko, S.; Horbas, S.; Tovstukha, O. Criteria for evaluating the state of rare plant species populations. Mod. Phytomorphol. 2023, 17, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.H. China: Mother of Gardens; Stratford Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.; Zhang, L.; Kang, S.; Ren, F.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Jia, Q. Comprehensive evaluation of the nutritional properties of different germplasms of Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua. Foods 2024, 13, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Huang, Y.; Quan, J.; Pei, L.; Lei, M.; Cao, H. Resource investigation and evaluation system establishment of endangered medicinal plants in Jinfo Mountain. J. Trop. Subtrop. Bot. 2016, 24, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.C. Medicinal plants, conservation and livelihoods. Biodivers. Conserv. 2004, 13, 1477–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippmann, U.; Leaman, D.J.; Cunningham, A.B. Impact of Cultivation and Gathering of Medicinal Plants on Biodiversity: Global Trends and Issues. In Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries; Inter-Departmental Working Group on Biological Diversity for Food and Agriculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S.; Lu, L. Application and prospect of evolutionary ecology in evaluation of germplasm resources of medicinal plants. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2021, 52, 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.P.; Cao, Z.; Zhao, X.F.; Zhao, L.X. Collection, conservation, utilization and evaluation of plant germplasm resource in USA. Pratacultural Sci. 2007, 24, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, W. Advances of the apricot resources collection, evaluation and germplasm enhancement. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2018, 45, 1642–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutika, L.S.; Rainey, H.J. A review of the invasive, biological and beneficial characteristics of aquatic species Eichhornia crassipes and Salvinia molesta. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2015, 13, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, Y.; Yamasaki, M.; Isagi, Y.; Ohgushi, T. An exotic herbivorous insect drives the evolution of resistance in the exotic perennial herb Solidago altissima. Ecology 2014, 95, 2569–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.X.; Wang, S.S.; Lin, X.T.; Mao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cai, Y.; Deng, C. Risk assessment of ornamental introduced plants in Xiamen Island coastal park. Chin. J. Trop. Crops 2024, 45, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yuan, M.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, G. Landscape plants’ regional research and conservation. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 675–677, 1097–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.S.; Pagano, E.M. Evaluation of introduced and naturalised populations of red clover (Trifolium pratense L.) at Pergamino EEA-INTA, Argentina. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2005, 52, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, R.; Batista, L.A.R.; Negreiros, G.D.; de Carvalho, J.R.P. Agronomical evaluation and selection of forage pigeon-pea germplasm (Cajanus cajan (L.) Milsp) from India. Rev. Da Soc. Bras. De Zootec.-J. Braz. Soc. Anim. Sci. 1997, 26, 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.B.; Goodman, M.M.; Castillo-Gonzalez, F. Identification of agronomically superior Latin American maize accessions via multi-stage evaluations. Crop Sci. 1996, 36, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yu, H.; Gu, Y.; Liu, J.; Gao, W. Integrated assessment of phenotypic traits and bioactive compounds in Astragalus membranaceus var. mongholicus. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munda, S.; Paw, M.; Saikia, S.; Begum, T.; Baruah, J.; Lal, M. Stability and selection of trait specific genotypes of Curcuma caesia Roxb. using AMMI, BLUP, GGE, WAAS and MTSI model over three years evaluation. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2022, 32, 100446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, T.; Thacker, D.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, T. Germplasm resources and genetic breeding of Paeonia: A systematic review. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.J.; Yu, A.Q.; Wang, Z.B.; Meng, Y.H.; Kuang, H.X.; Wang, M. Genus Paeonia polysaccharides: A review on their extractions, purifications, structural characteristics, biological activities, structure-activity relationships and applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.J.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, S.; Sun, X.M.; Wang, X.T.; Wang, Z.B.; Wu, Y.L.; Wu, J.; Li, Y. A breakthrough in phytochemical profiling: Ultra-sensitive surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy platform for detecting bioactive components in medicinal and edible plants. Microchim. Acta 2024, 191, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, F.; Dong, L.; Cheng, X. Assessment of Vertical Greening Plants in Cities with Hot Summers and Cold Winters: A Case Study in Chongqing. In 2024 the 8th International Conference on Energy and Environmental Science and Engineering (ICEES 2024); Liu, Y., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Hou, M.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J. Volatile compounds evaluation and characteristic aroma compounds screening in representative germplasm of mei (Prunus mume) based on metabolomics and sensomics. Food Chem. 2025, 489, 144994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Yanmaz, R. Use of ornamental vegetables, medicinal and aromatic plants in urban landscape design. Acta Hortic. 2010, 881, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.M.; Yu, Z.W.; Fang, B.C.; Wu, L.R.; Wang, L.F. Resources and development prospect of medicinal and ornamental plants in Thousand-island Lake. J. Zhejiang For. Sci. Technol. 2003, 23, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dhyani, D.; Singh, S. Domestication and conservation of Incarvillea emodi: A potential ornamental wild plant. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2010, 80, 182–185. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.P.; Yao, L.F.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, Z.G. Current status and ornamental potential of endangered dwarf peony in China. Acta Hortic. 2008, 769, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.M.; Yang, W.; Zhu, S.Y.; Wei, J.A.; Zhou, X.L.; Wang, M.L.; Lu, H.X. Evaluation of aromatic characteristics and potential applications of Hemerocallis L. based on the analytic hierarchy process. Molecules 2024, 29, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Xu, W.; Yu, L. Investigation and evaluation of ornamental ferns in Beijing area. Acta Hortic. 2009, 813, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.F.; Feng, Y.; Yue, L.J. Distribution, collection and evaluation of Iris species in southwest China. Acta Sci. Pol.-Hortorum Cultus 2021, 20, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, G.; Qu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, L.; Su, J.; Lei, J. Collection and evaluation of wild tulip (Tulipa spp.) resources in China. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2017, 64, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Gao, Z.M. Preliminary study on the characteristics of growth and development in Salvia miltiorrhiza. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2007, 35, 5783–5785. [Google Scholar]

- Gaihre, Y.R.; Tsuge, K.; Hamajima, H.; Nagata, Y.; Yanagita, T. The contents of polyphenols in Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens (Egoma) leaves are determined by vegetative stage, spatial leaf position, and timing of harvesting during the day. J. Oleo Sci. 2021, 70, 855–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.B.; Zhang, X.; Fan, L.S.; Jin, X.J.; Wang, H.Y.; Cheng, J.L.; Wang, C.Y.; Fang, Q. Quantitative comparison of yield, quality, and metabolic products of different medicinal parts of two types of Perilla frutescens cultivated in a new location from different regions. Plants 2025, 14, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.L.; Li, Z.R.; Shao, Z.Q.; Zheng, C.C.; Zou, H.J.; Zhang, J.J. Lead tolerance and enrichment characteristics of several ornamentals under hydroponic culture. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2020, 105, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, W.H.; Steppe, K. Perspectives for remote sensing with unmanned aerial vehicles in precision agriculture. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, G.; Sandhu, N.; Anderson, D.; Catolos, M.; Hassall, K.L.; Eastmond, P.J.; Kumar, A.; Kurup, S. Laboratory phenomics predicts field performance and identifies superior indica haplotypes for early seedling vigour in dry direct-seeded rice. Genomics 2021, 113, 4227–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F.L.; He, M.Z.; Zheng, Z.W. Data augmentation using improved cDCGAN for plant vigor rating. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 175, 105603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.D.; Wang, L.Q.; Tian, T.; Yin, J.H. A review of unmanned aerial vehicle low-altitude remote sensing (UAV-LARS) use in agricultural monitoring in China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruganantham, P.; Wibowo, S.; Grandhi, S.; Samrat, N.H.; Islam, N. A systematic literature review on crop yield prediction with deep learning and remote sensing. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Shukla, A.; Goswami, O.P.; Alsharif, M.H.; Uthansakul, P.; Uthansakul, M. Plant leaf disease detection, classification, and diagnosis using computer vision and artificial intelligence: A review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 37443–37469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.P.; Li, K.; Xia, Y.P. Green period characteristics and foliar cold tolerance in 12 Iris species and cultivars in the Yangtze Delta, China. HortTechnology 2017, 27, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.B.; Shi, X.H.; Zhang, R.L.; Zhang, K.J.; Shao, L.M.; Xu, T.; Li, D.Q.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.P.; Xia, Y.P. Impact of summer heat stress inducing physiological and biochemical responses in herbaceous peony cultivars (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.) from different latitudes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 184, 115000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.Y.; Ying, J.J.; Fang, L.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.P.; Mao, X.Q.; Wang, H.R. First report of Fusarium solani causing fusarium wilt of Bletilla striata (Hyacinth Orchid) in Zhejiang Province of China. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Manzoor, M.A.; Ren, Y.S.; Guo, J.J.; Zhang, P.F.; Zhang, Y.Y. Exogenous melatonin alleviates sodium chloride stress and increases vegetative growth in Lonicera japonica seedlings via gene regulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Zheng, M.Q.; Shen, Z.J.; Meng, H.Y.; Chen, L.H.; Li, T.T.; Lin, F.C.; Hong, L.P.; Lin, Z.K.; Ye, T.; et al. Tolerance enhancement of Dendrobium officinale by salicylic acid family-related metabolic pathways under unfavorable temperature. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.Y.; Yan, C.; Li, S.; Tang, H.; Chen, Y.H. Comparative physiological responses and transcriptome analysis revealing the metabolic regulatory mechanism of Prunella vulgaris L. induced by exogenous application of hydrogen peroxide. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 192, 116065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Q.; Li, W.J.; Xiao, M.F. Comparison of active components in different parts of Perilla frutescens and its pharmacological effects. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi = China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2023, 48, 6551–6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Su, J.; Hui, B.D.; Gong, P. Heavy metal determination of Houttuynia cordata Thunberg from coal mining fields. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2016, 37, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.C.; Zhuang, C.W.; Xuan, J.; Huang, L.J. Evaluation on development and application of wild ornamental grasses in nature reserves of Guangdong Province. Pratacultural Sci. 2023, 40, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tang, H.P.; Wang, S.; Hu, W.J.; Li, J.Y.; Yu, A.Q.; Bai, Q.X.; Yang, B.Y.; Kuang, H.X. Acorus tatarinowii Schott: A review of its botany, traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Molecules 2023, 28, 4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.Q.; Wang, B.L.; Ma, J.S.; Li, C.Y.; Zhang, Q.J.; Zhao, Y.H. Impatiens balsamina: An updated review on the ethnobotanical uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 303, 115956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.Y.; Li, C.H.; Dou, J.X.; Liang, J.; Chen, Z.Q.; Xu, Z.S.; Wang, T. Research progress on pharmacological properties and application of probiotics in the fermentation of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1407182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.X.; Liao, M.X.; Deng, T.L. Species and quality of geo-authentic Ligusticum chuanxiong in Sichuan Province. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2004, 35, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.C.; Lu, C.F.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, F.F.; Gui, A.J.; Chu, H.L.; Shao, Q.S. Chrysanthemum morifolium as a traditional herb: A review of historical development, classification, phytochemistry, pharmacology and application. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 330, 118198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.X.; Li, Q.Z.; Yang, L.Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.C. Changes in carbohydrate metabolism and endogenous hormone regulation during bulblet initiation and development in Lycoris radiata. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Jin, J.; Zhou, R.R.; Fang, L.Z.; Liu, H.; Zhong, C.; Xie, Y.; Liu, P.A.; Qin, Y.H.; Zhang, S.H. Integrative analysis of metabolome and transcriptome provide new insights into the bitter components of Lilium lancifolium and Lilium brownii. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 215, 114778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, L.P.; Lei, J.J.; Wang, C. Collection and evaluation of the genus Lilium resources in Northeast China. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2011, 58, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.R.; Zhang, Y.B.; Huang, S.C.; Zhan, Q.W.; Jiang, Z.Y. Response of the growth of Ophiopogon japonicus and its physiological characteristics to aluminum stress. Pak. J. Bot. 2020, 52, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.C.; Yu, Q.; Wang, F.W.; Bai, G.; Wang, Q.; Li, S.; Li, Y. Changes of floral color and pigment content during flowering in several species of Lonicera L. J. Southwest Univ. 2020, 42, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, M.; Zeng, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Han, H.; Du, C.; Shen, Q. Resources collection and leaf color diversity analysis of Perilla frutescens (L.) in Guizhou Province. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2013, 29, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. Study on the ornamental value and reproductive habits of Duchesnea indica. Pract. For. Technol. 2008, 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.G.; Li, J.J.; Song, J.; Guo, Q.R. The SSR genetic diversity of wild red fruit Lycium (Lycium barbarum) in Northwest China. Forests 2023, 14, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Cai, X.K.; Tian, M.; Xie, G.Y.; Qin, M.J. Researches on flowering characteristics and breeding system of Belamcanda chinensis. J. Plant Resour. Environ. 2019, 28, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Demirci, B.; Göppel, M.; Demirci, F.; Franz, G. HPLC profiling and quantification of active principles in leaves of Hedera helix L. Die Pharm. 2004, 59, 770–774. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.P.; Zhang, H.M.; Yin, Y.L.; Liang, Y.W.; Zhou, P.; Hao, M.Z.; Zhang, D.L. ‘Jingshan Princess’: A new Ilex ×attenuata cultivar with entire leaf margin and yellow foliage. HortScience 2024, 59, 1393–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafi, M.; Showker, T. A comparative study of saffron agronomy and production systems of Khorasan (Iran) and Kashmir (India). Acta Hortic. 2007, 739, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Chen, J.S. A scoring method on a 100-point scale—A new approach to establishing and applying selection standards for citrus trees. J. Huazhong Agric. Coll. 1956, 84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.Z. Application of the analytic hierarchy process in the adjustment of forest tree species structure. East China For. Manag. 1988, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, L.M. Comprehensive evaluation of forest harvest adjustment using the analytic hierarchy process. For. Resour. Manag. 1990, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.Y.; Deng, C.Z. Experiment on selecting superior cultivars of three Camellia species using a 100-point scoring method. J. Beijing For. Univ. 1986, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.L.; Li, X.H.; Wang, Z.Q. Comprehensive evaluation of medicinal plant resources based on the analytic hierarchy process. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2015, 40, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, J.G.; Zhang, L. Evaluation of medicinal plant development potential and resource utilization based on the analytic hierarchy process. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017, 37, 5520–5528. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J. Construction and application of an evaluation index system for the landscape value of medicinal-ornamental plants: A case study of a park. Gardens 2018, 34, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N. Construction and application of a comprehensive evaluation system for Chinese medicinal plant resources. Chin. Herb. Med. 2019, 50, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Wu, F.; Wang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Chen, C.; Wei, Y. Evaluation system and application of plants in healing landscape for the elderly. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 58, 126969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.L. An introduction to grey system theory. Inn. Mong. Electr. Power 1993, 3, 51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.C.; Shang, F.D.; Xiang, Q.B. Comprehensive evaluation methods for plant cultivars: A case study of Osmanthus fragrans. J. Henan Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2003, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.Y. Biological and Morphological Characteristics of Central Plains Peony Cultivars. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.W. Evaluation and Diversity Study of Wild Ornamental Plant Resources in Fujian. Master’s Thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.H. Quantitative evaluation of ornamental traits of wild ornamental plants. East China For. Manag. 2005, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.D.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Jiang, X.W.; Chen, M.G.; Zheng, J.S.; Chen, W.R. Determination of semi-lethal temperature and analysis of cold tolerance in Citrus medica under low-temperature stress. Sci. Hortic. Sin. 2009, 36, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.D.; Zhai, X.Y.; Shi, B. Cold tolerance of yellow-leaved and purple-leaved Hamamelis cultivars. J. Northeast For. Univ. 2011, 39, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.P.; Li, D.Q.; Nie, J.J.; Xia, Y.P. Physiological and biochemical responses to the high temperature stress and heat resistance evaluation of Paeonia lactiflora pall. cultivars. J. Nucl. Agric. Sci. 2016, 30, 1848–1856. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.-H.; Yong, S.-H.; Park, D.-J.; Ahn, S.-J.; Kim, D.-H.; Park, K.-B.; Jin, E.-J.; Choi, M.-S. Efficient cold tolerance evaluation of four species of Liliaceae plants through cell death measurement and lethal temperature prediction. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, A.M.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.L.; Baek, J. Image-based high-throughput phenotyping in horticultural crops. Plants 2023, 12, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, T.; Absar, N.; Adamov, A.Z.; Khandaker, M.U. A Machine Learning Driven Android Based Mobile Application for Flower Identification. In Communications in Computer and Information Science; AII 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1435, pp. 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, X.; Wen, L.; Cui, Y.; Wang, X.; Ren, Z.; Ye, Y.; Xia, Y.; Li, D. Advances and Perspectives in Comprehensive Assessment of Medicinal–Ornamental Multifunctional Plants. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121454

Feng X, Wen L, Cui Y, Wang X, Ren Z, Ye Y, Xia Y, Li D. Advances and Perspectives in Comprehensive Assessment of Medicinal–Ornamental Multifunctional Plants. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121454

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Xiaowen, Lijie Wen, Yunqing Cui, Xueming Wang, Ziming Ren, Yihan Ye, Yiping Xia, and Danqing Li. 2025. "Advances and Perspectives in Comprehensive Assessment of Medicinal–Ornamental Multifunctional Plants" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121454

APA StyleFeng, X., Wen, L., Cui, Y., Wang, X., Ren, Z., Ye, Y., Xia, Y., & Li, D. (2025). Advances and Perspectives in Comprehensive Assessment of Medicinal–Ornamental Multifunctional Plants. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121454