Abstract

Sulphur dioxide (SO2) is mostly used as an antioxidant additive in winemaking, but excessive levels may be harmful to both wine quality and consumers health. During fermentation, yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae contributes significantly to final SO2 levels, and low-producing strains become especially interesting for the wine industry. Recent evidence implicating the impairment of sulphate transport in the SO2 decrease prompted us to further investigate the sulphate/sulphite metabolic connection in multiple winery yeast strains. Here, we inactivated by CRISPR/Cas9 the high-affinity sulphate permeases (Sul1p and Sul2p) in four strains normally used in winemaking, selected by their different abilities to produce SO2. Mutant strains were then used to perform fermentation assays in different types of natural must, and the final levels of SO2 and other secondary metabolites, crucial for wine organoleptic properties, were further determined for all fermentation products. Overall, data demonstrated the double ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 inactivation in winery strains significantly decreases the levels of SO2 produced by mutant cells, without however altering both yeast fermentative properties and the ability to release relevant metabolites. Since similar effects were observed in diverse must types for strains with different features, the data strongly support that sulphate assimilation is the determining factor in SO2 production during oenological fermentations.

1. Introduction

Sulphur dioxide (SO2) is widely used in oenology as an antioxidant and antimicrobic additive, from the earliest stages to final wine production [1]. Indeed, SO2 is used to prevent undesired microorganism proliferation in the must but also to select the more resistant S.cerevisiae yeast strains, which actually perform the fermentation process. Moreover, SO2 may promote the decantation of the solid parts (in white wines) as well as the extraction of colour and tannins from the skins (in red wines). As an antioxidant, SO2 is employed in all operations involving the contact of the wine with the air (e.g., racking, clarification, filtration, and bottling), thus avoiding the oxidation of many molecules crucial to defining the organoleptic properties of the wine [2].

In solution, sulphur dioxide dissociates into three different species, i.e., molecular SO2 (H2O•SO2), bisulphite (HSO3−), and sulphite (SO3--), whose proportions are regulated by pH and thermodynamic constants. In the acidic conditions typical of must and wine, the dominant form is the bisulphite ion, while molecular SO2 levels are limited [3]. Since its high chemical reactivity, SO2 can further combine with some components of either must or wine, such as sugars, ketone acids, uronic acids, and anthocyanins [4]. These interactions are characterised by different affinities, distinguishing compounds weakly associated with SO2 from molecules permanently bound, such as acetaldehyde. In wines, the amount of free sulphur dioxide added to the combined amount determines the total SO2.

Despite the positive effects on wine, the use of SO2 has to be limited, both for the negative effects on health and for organoleptic reasons, as excessive levels of this compound in wine can lead to an accumulation of acetaldehyde and the production of hydrogen sulphide (H2S) and mercaptans, with consequent undesired odours. In each country, the maximum quantities allowed in oenology are established by specific laws: in the European Union, the SO2 limits are 160 mg/L for red wines and 210 mg/L for white and rosé wines [5]. Moreover, since SO2 is classified as an allergen, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has defined the maximum daily dose as 0.7 mg/kg of body weight, while the lethal dose is defined as 1.5 g/kg of body weight. In this regard, it should be noted that in individuals predisposed to and sensitive to SO2, this can be a cause of migraines as well as other diseases (e.g., hypotension, cardiovascular problems, and asthma) [6,7].

Remarkably, SO2 levels in the final wine result not only from exogenous additions throughout the process but also from the cellular metabolism of the yeast S.cerevisiae during fermentation [8]. Indeed, yeast cells require sulphur to perform the biosynthesis of the sulphur-containing aminoacids (methionine and cysteine) and their derivatives, primarily S-Adenosyl Methionine (SAM) and Glutathione (GSH), which are essential to proper cell growth and proliferation [9]. The main sulphur source for S.cerevisiae cells is inorganic sulphate (SO4--), largely available in the must, where its concentration may vary from 160 to 380 mg/L [10], or even higher (700–1200 mg/L) [11,12].

Sulphate uptake in the yeast cells is mainly mediated by two high-affinity permeases, the Sul1p and Sul2p proteins [13,14,15], while a low-affinity transporter has been recently identified (Soa1p) [16]. Once internalised, SO4-- enters the Sulphate Assimilation Pathway (SAP), where it is reduced to sulphide (S--) through a series of four enzymatic reactions, catalysed by ATP-sulfurylase (Met3p), adenylylsulfate kinase (Met14p), 3′-Phospho-5′-Adenylylsulphate (PAPS) reductase (Met16p), and sulphite reductase (Met5p/Met10p). Then, sulphide is combined with O-acetyl homoserine by the homocysteine synthase (Met25p) to form homocysteine, which can then be converted to methionine and cysteine, and finally to their derivatives as SAM and GSH [9].

Importantly, insufficient assimilable nitrogen in must, limiting O-acetyl homoserine levels, as well as excessive sulphate and hyperactivation of the SAP pathway, can lead to the accumulation of reduction intermediates, mainly SO2 and/or H2S, which are finally excreted as metabolic by-products [17,18,19]. In winery S.cerevisiae species, SO2 release has been so far reported as a strain-specific feature [20], with the production of SO2 levels ranging from a few mg/L to more than 100 mg/L, depending also on the fermentation conditions [21,22]. Noteworthy, SO2 levels are strictly connected to the release of other compounds with organoleptic properties, such as acetaldehyde. Indeed, SO2 directly promotes acetaldehyde production by yeast cells, and wines fermented with SO2 addition have considerably higher acetaldehyde levels than wines made without SO2 [23,24]. The amount of sulphur compounds in the wine is therefore crucial to its acceptability for marketing [25], as excessive yeast production of hydrogen sulphide could have a negative aromatic impact (i.e., rotten egg) [19], while high levels of sulphites could represent a source of health concerns [6,7].

For this reason, the availability of yeast strains able to produce low levels of such sulphur by-products constitutes a major interest for the wine industry. In the last decade, different H2S low-producer yeast strains have been selected directly from vineyard isolates [25], as well as upon chemical mutagenesis of selected strains [26], revealing that defective SAP enzymes (e.g., sulphite reductase) lead to the decrease of sulphide release by yeast cells. Additional approaches, such as yeast strain evolution or genetic improvement based on massive sexual recombination of spores, have been successfully performed to either reduce the levels of sulphur compounds [27] or increase the production of GSH [28].

Furthermore, promising results have been obtained using toxic analogues of sulphate (e.g., selenate, chromate, and molybdate) [29] to select yeast strains carrying mutations of genes involved in sulphate assimilation after massive meiotic recombination [30] or treatment with chemicals (e.g., Ethyl Methane Sulphonate, EMS) to induce random mutagenesis [31]. Notably, data demonstrated that single inactivation of either Sul1p or Sul2p permeases in the wine strain EC1118 was causative of sulphide and (to a lesser extent) sulphite production [31], pointing to the connection between sulphate uptake/transport and the release of sulphur by-products.

However, some questions remain to be addressed, concerning the functional effects of the SUL1/SUL2 double inactivation on the cells of wine yeast strains; then, whether such effects are occurring in all yeast strains, regardless of their different properties as sulphite producers; finally, check the consequences of the mutation of sulphate transporters on the release of other metabolites, produced by yeast cells during fermentation, that are sensory relevant to the wine.

Therefore, we investigate here the relationships between SO4-- uptake and SO2 production, by the complete elimination of the high-affinity transport system in different winery strains, selected since their intrinsic ability to release sulphites (i.e., high or low levels). Notably, by the CRISPR/Cas9 technique, we have generated mutant yeast strains carrying either a single or double SUL1/SUL2 deletion, which have been then analysed for the cellular properties, the fermentative performance, and the ability to produce SO2. Moreover, the levels of relevant metabolites released during the fermentation of natural products must have been evaluated by biochemical HPLC and GC-MS assays.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast Strains and Media

The winery Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used belong to the proprietary collection of Italiana Biotecnologie S.r.l. (Italy), further deposited and conserved at DBVPG (University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy): (1) strain STR (source: Italy; DBVPG #52SF); (2) strain HIGH (source: USA; DBVPG #36SF); (3) strain MED (source: Italy; DBVPG #29SF); and (4) strain LOW (source: Italy; DBVPG #41SF). All strains have been sequenced, and genomic data have been reported in [32], where the IDs were respectively IT-DBK_S2; IT-DBL_S3; IT-DBR_S9; and IT-DBU_S12.

Yeast strains were maintained by growth in standard rich medium (YPG, Yeast extract 10 g/L, Bacto Peptone 10 g/L, glucose 20 g/L), eventually supplemented with antibiotic (G418, 0.2 g/L) for strain selection. Functional assays were either performed in YPG added with the SO4-- toxic analogue Na2SeO4 or in a minimal medium SD (without aminoacids) containing standard SO4-- concentrations (glucose 20 g/L, yeast nitrogen base 1.7 g/L, and ammonium sulphate 5 g/L), or in conditions where SO4-- levels were limited (glucose 20 g/L, yeast nitrogen base 1.7 g/L, and ammonium chloride 2 g/L), and eventually supplemented by methionine (80 mg/L). The production of H2S has been evaluated by the behaviour of the yeast strains to grow on the BiGGY agar-specific medium, as already reported [26]. Media components and chemicals, as reagents for auxotrophic requirements and antibiotics, were sourced from Difco (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA), respectively.

2.2. Bacterial Strains and Media

StellaR (Clontech) competent Escherichia coli cells [(F-, endA1, supE44, thi-1, recA1, relA1, gyrA96, phoA, Φ80d lacZΔ M15, Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169, Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC), and ΔmcrA, λ-)] were used as a host for cloning procedures and plasmid propagation. E. coli cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB; Bacto tryptone 10 g/L; Yeast extract 5 g/L; and NaCl 5 g/L) at 37 °C with 0.1 mg/mL ampicillin if required.

2.3. Plasmids Construction

All newly generated plasmids (listed in Supplementary Table S2) were obtained using the In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Takara-bio, USA, Inc. (San Jose, CA, USA) Cat. Nos. Many (102518)), including the design of the primers used (reported in Supplementary Table S2). The pMEL13-NotI plasmid was generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the Quikchange kit (Agilent) to include the unique restriction site (NotI) into the gCANY.1 sequence of pMEL13 [33], using the mutagenic primers pMEL-NotI-F and R. The pMEL13-NotI-Cas9 plasmid was obtained by In-Fusion cloning (in the SalI site of the pMEL13-NotI vector) of the expression cassette pTEF-Cas9-TEFter, obtained by PCR amplification from IMX585 [33] genomic DNA as template and the Cas9-pMEL F and R primers. The gSUL1-pMEL13-Cas9 and gSUL2-pMEL13-Cas9 plasmids were generated by In-Fusion assembly using the PCR fragments obtained by coupling the 6006 F primer with either the gSUL1-target R or gSUL2-target R primers, respectively. Such primers replaced the parental pMEL13-Cas9 sequence (gCAN1.Y-NotI) with the guide sequence to target either the SUL1 or SUL2 genes, respectively. All recombinant plasmids isolated from bacterial clones grown onto selective LB plates were further verified both by restriction digestion and by sequencing.

2.4. Yeast Genetic Modification

Yeast manipulation was performed following standard protocols [34,35]. Cells were transformed using the PEG/lithium acetate method [36] and selected on solid media supplemented with G418 as reported. The deletion of SUL1 and SUL2 genes was achieved via co-transformation of yeast strains with 1 μg of either gSUL1-pMEL13-Cas9 or gSUL2-pMEL13-Cas9 plasmids (targeting the SUL1 or SUL2 locus, respectively) and 3 μg of donor dsDNA, consisting of 100 bp DNA fragments (ds-ΔSUL1 or ds-ΔSUL2) obtained by mixing (1:1) either ssDNA ssSUL1 repair F and R, or ssSUL2 repair F and R, oligonucleotides. Genetic modifications occurred sequentially, i.e., all strains were first modified in the SUL1 locus. Then, the deletion of SUL2 was inserted in both ΔSUL1 and the parental strain to generate double ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 and single ΔSUL2 isogenic mutant strains. Gene deletions in recombinant clones were confirmed by site-specific PCR assays using appropriate diagnostic primers. Genotype analyses of single and double mutant strains were performed by PCR analysis of inter-delta regions using the δ12 and δ21 primers as described [37].

2.5. Yeast Functional Assays

The viability of yeast strains was analysed by evaluating the growth of yeast cells on solid media with the spot assay, as already reported [38]. Briefly, exponentially growing yeast cultures of each strain were normalised to OD600 = 1.0, serially diluted (1:10), and spotted (5 μL) on the appropriate selective solid media (as indicated in the Figure legends). Plates were then incubated for 2–3 days at 28 °C. Images in Figures are representative of (at least) 2–3 independent experiments.

2.6. Fermentation Assays

Fermentation data were collected from 2–4 independent experiments using natural grape juices of different origins, as detailed in Supplementary Table S3, where sugars were adjusted (to 204 g/L) and nitrogen supplemented (with diammonium phosphate 200 mg/L and yeast extract 300 mg/L). Overall, S. cerevisiae yeast cells were inoculated at 106 cfu/mL in 175 mL of must, and static fermentations were conducted at 20 °C in a Pyrex bottle closed with caps (RF1 modules) of the ANKOMRF Gas Production System, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ANKOM Technology, 2052 O’Neil Road, Macedon, NY 14502, USA). The system recorded the pressure of the CO2 produced by the fermentation every 30 min to constantly monitor the process. The pressure increase was used to indirectly determine the percentage of ethanol present in the wort every 30 min fermentation, and data analysis resulted in the traces being represented as fermentation kinetics. After the end of fermentation, the products were racked and held at 4 °C to perform the chemical analyses.

2.7. Chemical Analyses

The levels of ethanol in fermented products were directly determined using Alcolyzer Wine M (Anton Paar), which determines the content of ethanol by near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy. Free and total sulphur dioxide content (mg/L) was determined by the Steroglass FLASH automatic titrator with an AS24 autosampler and a platinum redox electrode (Accsen EL450C), based on the Ripper–Schmitt method [39]. Acetaldehyde content was measured by a commercial K-ACHYD 01/20 assay kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Megazyme, Bray, Ireland). The residual sugar content and the levels of glycerol and some organic acids (citric, tartaric, malic, succinic, and acetic), were analysed by HPLC after sample processing (centrifugation, dilution, and filtration (0.2 μm)). The HPLC instrument was an Agilent 1200 Series–BIORAD, column Aminex HPX-87H (300 × 7.8 mm); mobile phase: H2SO4 0.005 M; detectors: VWD (Variable Wavelength Detector; λ = 210 nm) and RID (Refractive Index Detector; 35 °C). To extract volatile compounds from samples, a preparative step of solid-phase extraction was performed using SPE cartridges (Macherey-Nagel CHROMABOND Easy 3 mL/200 mg), which were conditioned with 3 mL of water-ethanol solution (6% v/v). A volume of 25 mL of wine was filtered at 0.2 μM and diluted 1:1 with water. Then, 40 μL of the 2-octanol internal standard (6.3 mM in ethanol) was added. The sample was eluted through the SPE cartridge at around 2 mL/min, and then the sorbent was dried by passing air through it. Analytes were collected by eluting with two aliquots of dichloromethane (2 × 1.0 mL). The samples were sealed tightly and analysed by GC-MS with the instrument GC Perkin Elmer Clarus 580 25 coupled with the Perkin Elmer SQ8S MS detector. The capillary column used is a Perkin-Elmer WAX-ETR (30 m × 0.32 mm ID × 0.25 μm), and helium (1.5 mL/min) was used as the carrier gas. The ramp of temperature of the gas chromatograph is 40 °C for 1 min, 5 °C/min up to 240 °C maintained for 5 min. A total of 1 μL of the sample was injected into the instrument via an autosampler. The injector (SPLIT/SPLITLESS) was set at a temperature of 250 °C and 20 mL/min.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The data were analysed using Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error (SEM). The number of replicates (n) reported in the figure legends indicates the number of cultures/transformations. Statistics were based on the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s post-hoc test or an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, as reported in the figure legends. It was assumed to be statistically significant if the p-value < 0.05 (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01). The GC-MS data (reported in Supplementary Table S1) were analysed by performing an unsupervised multivariate principal component analysis (PCA) using the SIMCA (version 13.0, Sweden Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden) software. Setting parameters were as follows: model type, PCA-X; scaling; and unit variance.

3. Results

3.1. Construction of CRISPR/Cas9 Tools for Genome Editing of Natural Yeast Strains

One of the major problems that can arise in the genome manipulation of natural yeast strains is the absence of the classical nutritional auxotrophic mutations. Normally present in selected laboratory strains, they allow, in combination with vectors carrying the corresponding marker genes, the modification of the genome by standard selection of specific recombination events. Thus, we built a unique plasmid tool to make it easier to perform genome editing in any natural yeast strain. Briefly, starting from the CRISPR/Cas9 yeast tools already described [33], we modified the pMEL13 plasmid firstly by the introduction of a unique NotI site in the gDNA CAN1.Y region and then by the insertion of the spCas9 cassette for the expression of the Cas9 nuclease. The detailed procedures for DNA manipulation and cloning are described in Materials and Methods. Starting from the pMEL13-NotI-Cas9 plasmid, we performed the substitution of the gDNA(CAN1.Y-NotI) region with the 20 bp guide sequences for the expression of gRNAs specific for either the SUL1 or SUL2 genes, finally generating the two plasmids gSUL1-pMEL13-Cas9 and gSUL2-pMEL13-Cas9, which were subsequently used for the inactivation of the two genes in the natural yeast strains (Supplementary Figure S1). We considered the two modifications introduced in the original pMEL13 plasmid to be particularly useful. Indeed, the introduction of the unique NotI site facilitated the screening of recombinant plasmids after the substitution of the gDNA region with the specific guide, while the presence of the SpCas9 coding sequence, together with the G418-resistance dominant marker in the same plasmid, allows the co-expression of the nuclease in any genetic background and can be used with any natural yeast strains, which are generally sensitive to the G418 antibiotic.

3.2. Yeast Genome Editing

The genetic modifications have been performed in four S. cerevisiae strains selected from a private collection (Italiana Biotecnologie S.r.l., Montebello Vicentino, Italy) of natural yeast strains actually used in winemaking, primarily considering their aptitude to produce SO2; during must fermentation, as indicated by previous experimental evidence. In particular, the four strains were featured as “strong”, “high”, “medium”, and “low” SO2; producers and, respectively, named STR, HIGH, MED, and LOW (see Section 2 Materials and Methods for details). Each strain was first modified by the deletion of the SUL1 gene, using the gSUL1-pMEL13-Cas9 plasmid to express the SUL1-specific RNA guide complexed with SpCas9 and the ∆SUL1 oligonucleotide as dsDNA repair, as indicated in Materials and Methods. The correctness of the genetic modification in yeast strain genomes was checked by locus-specific PCR using gene-specific diagnostic primers. The results of PCR analysis revealed a DNA fragment of approximately 570 bp amplified in all recombinant clones, supporting the hypothesis that the clones selected for each strain were correctly modified in the SUL1 gene (Supplementary Figure S2).

Thereafter, the deletion of the SUL2 gene was introduced in both wild-type and ΔSUL1 genetic backgrounds for each strain to generate single ∆SUL2 and ∆SUL1/∆SUL2 double mutants. As previously, the gSUL2-pMEL13-Cas9 plasmid was used, together with the ∆SUL2 oligonucleotide, for dsDNA repair. Again, the SUL2 locus-specific PCR analysis on several clones confirmed that the genetic modification properly occurred, as in the ∆SUL2 mutant cells, a fragment of approximately 800 bp was correctly observed (Supplementary Figure S2).

Finally, we investigated whether the CRISPR/Cas9 procedures could have additional effects on the genomes of single and double mutant cells, performing the analysis of their genotypes by the strain-specific inter-delta DNA profile [37]. Data from PCR assays excluded the introduction of undesired genome gross rearrangements (e.g., chromosomal translocations), as the mutant yeast strains displayed identical inter-delta patterns to the unmodified parental strains (Supplementary Figure S3).

3.3. Functional Characterization of Yeast Mutant Strains

Substantial evidence regarding the role in yeast cells of the proteins encoded by SUL1 and SUL2 genes as high affinity sulphate transporters has been mainly produced using laboratory strains (e.g., S288c and BY4741) [9,13], with sporadic studies analysing winery (commercial) strains [27,30,31]. It is therefore suggested to verify the effects of SUL1/SUL2 gene deletions in additional and different genetic backgrounds.

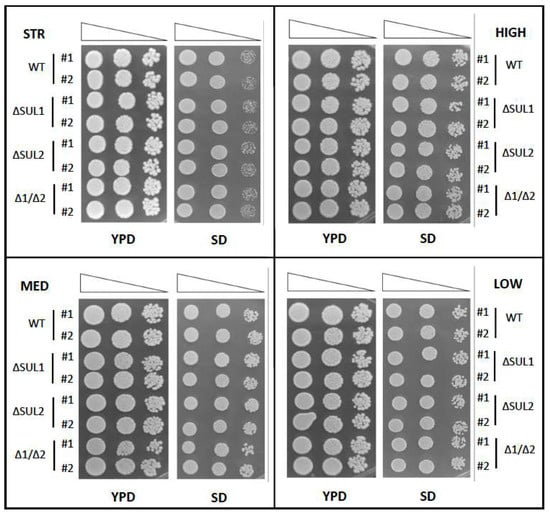

We first confirmed, for each S.cerevisiae strain, the full viability of the mutant cells in the presence of standard concentrations of sulphate. Indeed, the results of the growth assays (Figure 1) indicated for all four strains that the SUL1 and SUL2 gene mutations were not affecting yeast survival in both optimal (YPD) and minimal (SD) nutritional conditions, as the ability to grow either single or double mutant cells was almost identical to the corresponding wild-type strain.

Figure 1.

Viability assay of winery yeast strains carrying the deletion of SUL1 and/or SUL2 genes. Exponentially growing S. cerevisiae cells of the indicated strains (STR, HIGH, MED, and LOW) were serially diluted, spotted on rich (YPD) or minimal (SD) media plates, and incubated at 28 °C for 3 days. Two clones (#1 and #2) for each strain were compared, carrying either parental alleles (WT), deleted for SUL1 (ΔSUL1), SUL2 (ΔSUL2), or both genes (Δ1/Δ2). Images are representative of two independent experiments.

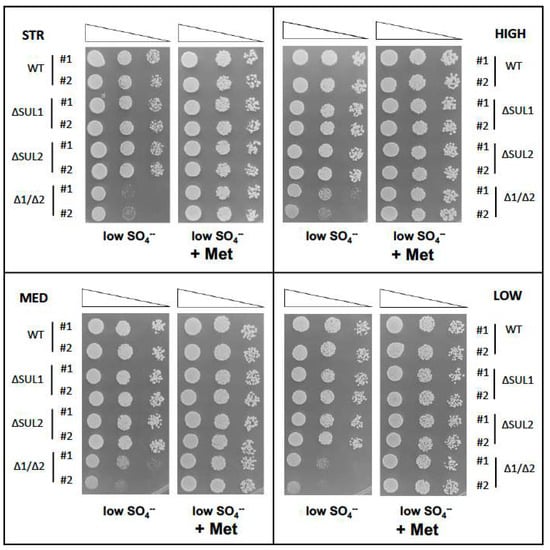

We then aimed to confirm that the mutation of sulphate permeases, impairing SO4-- transport into the cell, caused higher sensitivity to environmental SO4-- levels and that double mutant cells were auxotrophic for methionine, as reported for laboratory strains. Therefore, we assayed the growth of yeast cells on sulphate-limiting medium, where the double ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 mutants of all four strains were clearly affected in growth with respect to the wild-type cells (Figure 2). However, the addition of methionine to the medium completely restored the growth impairment of double mutant cells, which were able to proliferate as wild-type strains (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sulphate and methionine requirements of winery yeast strains deleted for SUL1 and/or SUL2 genes. As in Figure 1, S. cerevisiae cells of the indicated strains (STR, HIGH, MED, and LOW) were spotted on SD containing low SO4-- concentration, either without aminoacids (panels on left) or supplemented with methionine (panels on right), and incubated at 28 °C for 3 days. Two clones (#1 and #2) for each strain were compared, carrying either parental alleles (WT), deleted for SUL1 (ΔSUL1), SUL2 (ΔSUL2), or both genes (Δ1/Δ2). Images are representative of three independent experiments.

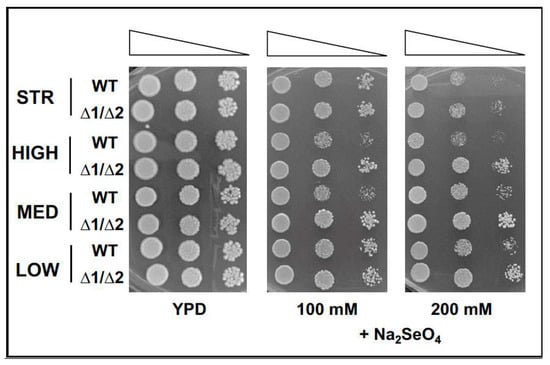

We further verified that the mutation of sulphate transporters led to an increased resistance of mutant yeast cells to toxic SO4---analogues of sulphate, as already evidenced [29,40]. So, we challenged the double ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 mutant cells for their sensitivity to the NaSeO4 toxic analogue by a series of growth assays on YPD medium added with increasing NaSeO4 concentrations. Although the different behaviours of the four strains likely reflect individual properties, the double mutant cells of all strains displayed higher resistance to NaSeO4 compared to wild-type, as demonstrated by the sustained growth even in the presence of high levels of toxic compound in the medium (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Yeast strains sensitivity to toxic SO4---analogues. As in Figure 1, yeast growth of parental (WT) and double mutants ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 (Δ1/Δ2) of the indicated strains (STR, HIGH, MED, and LOW) was assayed in the presence of increasing concentrations of NaSeO4 (100 and 200 mM, middle and right panels), and in standard YPD medium as the control (left panel). Images are representative of three independent experiments.

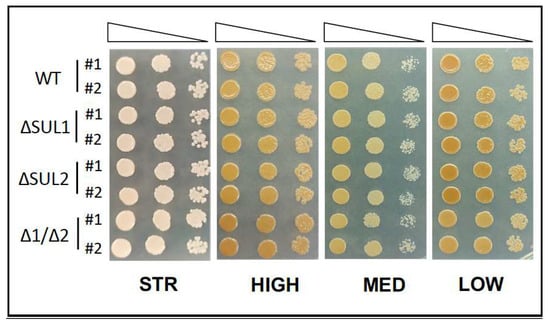

Despite previous experimental evidence indicating that the four strains were characterised as low H2S producers, we wanted to rule out the possibility that the mutation of either the SUL1 and/or SUL2 genes could perturb the release of H2S by yeast cells. Thus, we performed a growth assay on BiGGY-agar medium, which is commonly used to check the ability of yeast cells to produce H2S, and observed identical behaviour for wild-type and mutant cells (Figure 4), therefore indicating that the mutations of either the SUL1 and/or SUL2 genes were not impacting H2S release in all strains.

Figure 4.

Sulphide (H2S) production of the winery yeast strains. As in Figure 1, the STR, HIGH, MED, and LOW yeast strains, either parental (WT) or isogenic mutants (ΔSUL1, ΔSUL2, and Δ1/Δ2), were spotted in H2S-sensitive medium (BiGGY) to assay sulphide release, as the colour intensity of colonies is related to the levels of H2S production. Images are representative of two independent experiments.

Collectively, experimental data in the different winery strains recapitulated what had been so far observed in laboratory strains, further supporting the role of SUL1 and SUL2 gene products as high-affinity sulphate transporters also in winery strains, where the double ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 mutation markedly affected the growth of yeast cells under SO4---limiting conditions.

3.4. Fermentation Assays in Natural Must

The performances of all strains (wild-type and mutants) were then investigated by micro-fermentation assays in “Prosecco” natural must in order to check possible effects of either single and/or double SUL1/SUL2 gene mutations on yeast properties.

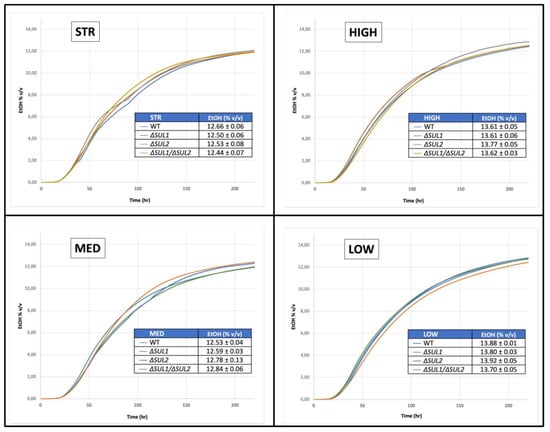

Fermentation processes were continuously monitored over time by the automatic measurement of the cumulative pressure generated by the CO2 released by yeast cells, which is directly related to ethanol production, allowing the calculation of the fermentative kinetics shown in Figure 5 (see Materials and Methods for details). Overall, data indicated very similar behaviour for all strains, as demonstrated by nearly overlapping kinetics and ethanol final levels, supporting a neutral influence of both single and double mutations on the fermentative capacity of the yeast strains with respect to the corresponding wild-type. Considering the main parameters (i.e., the initial/lag time (start), the trend of the curves, the time to complete the process, and the final alcohol), no significant differences occurred in the fermentations performed by all yeast strains in the four independent experiments, as also supported by statistical analysis.

Figure 5.

Fermentative performance of the winery yeast strains deleted for SUL1 and/or SUL2 genes. “Prosecco” natural must has been fermented using the indicated yeast strains (STR, HIGH, MED, and LOW), carrying parental (WT) or mutant alleles (ΔSUL1, ΔSUL2, or ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2). In each panel, the fermentation kinetics and the final levels of ethanol (inset Table) are reported. Traces represent the average of four independent experiments (errors omitted for clarity), without statistically relevant differences between the yeast strains.

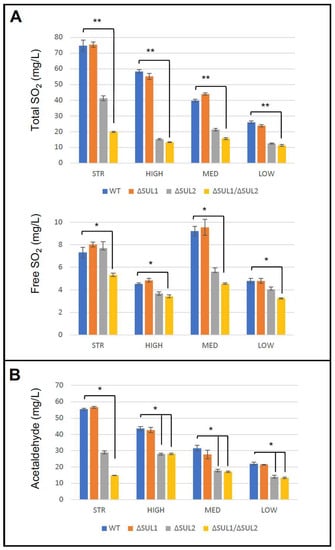

All fermentation products were then evaluated for SO2 levels by measuring free and total SO2. As expected, the four wild-type strains produced different amounts of SO2 during the fermentation of the same must, reflecting their strain-specific properties. In all strains, the impairment of SO4-- transport caused in mutant cells a reduction of both total and free SO2 levels, which were significantly decreased in double ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 mutants of all strains (Figure 6A). Interestingly, data suggested a major role for the SUL2 gene, as the effects of its loss appeared generally more pronounced than the SUL1 single mutation, according to [41]. Since the relationship between SO2 and acetaldehyde production during fermentation has been well established [23,24,42], we further determined in all samples the final levels of acetaldehyde. Mirroring what was observed for SO2, data indicated that the double ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 mutation significantly reduced in all strains the levels of acetaldehyde produced by the mutant cells, compared to wild-type strains (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

SO2 and acetaldehyde production by the winery yeast strains deleted for SUL1 and/or SUL2 genes. After the fermentation by the yeast strains (STR, HIGH, MED, and LOW), carrying parental (WT) or mutant alleles (ΔSUL1, ΔSUL2, or ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2), the levels of total and free SO2 (panel A) and acetaldehyde (panel B) have been determined as indicated in Materials and Methods. Values are expressed as mean ± S.E (n = 4). * p-value < 0.05; ** p-value < 0.01, and the Kruskal–Wallis test followed Dunn’s correction.

Fermentation products were then analysed to determine the levels of some important metabolites that contribute to the wine properties, and in all samples, we detected by HPLC some non-volatile compounds, such as residual sugars (glucose and fructose), glycerol, acetic acid, and main organic acids (citric, tartaric, malic, and succinic). The data reported in Table 1 indicated that the levels detected for all molecules were very similar in single or double mutant cells of each strain with respect to the corresponding wild-type cells, without significant differences among the four strains.

Table 1.

Levels of relevant metabolites detected by HPLC assay (values are expressed as mean ± S.E., n = 4).

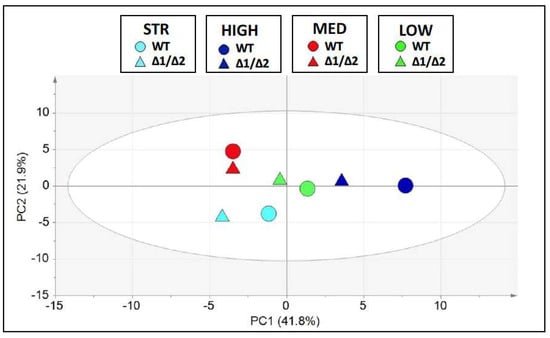

Additional investigations were performed on a subset of volatile metabolites by GC-MS analysis in wild-type and ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 samples, detecting the levels of 42 different compounds (Supplementary Table S1), possibly relevant to wine sensorial properties, which were clustered into four classes according to their chemical nature (i.e., higher alcohols, carboxylic acids, esters, and terpenoids). The total values in Table 2 were then calculated as the sum of the concentrations of each compound belonging to the category. Collectively, the data supported the conclusion that ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 mutations did not impair the yeast’s ability to produce all the secondary metabolites we investigated, as demonstrated by the similar levels detected in must samples fermented by mutant and wild-type strains.

Table 2.

Levels of main volatile compounds detected by GC-MS assay (values are expressed as mean ± S.E., n = 4).

We further performed Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the data of the volatile compounds, which revealed that the four wild-type strains were distributed in different map regions, reflecting strain-specific abilities to the aromatic outcome in wine. PCA data also supported the finding that the mutant strains on the map were distributed either very close to or in close proximity to the corresponding wild-type (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Principal component analysis (PCA). Score plot of the volatile compounds obtained by GC-MS data (see Supplementary Table S1) of WT (circles) and ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 (Δ1/Δ2, triangles) yeast strains. The four strains (STR, HIGH, MED, and LOW) are discriminated by using different colours. The percentage of variance explained by the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) is reported on each axis of the plot. Ellipse: Hotelling’s T2 (95%).

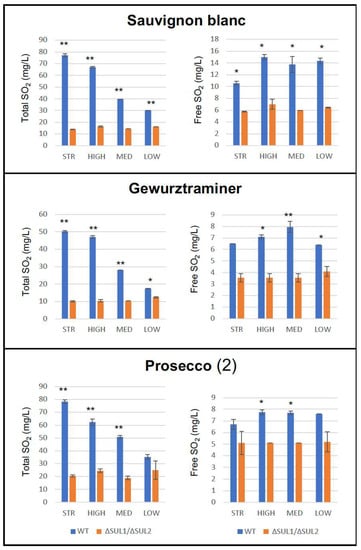

To extend our observations, we used the ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 double mutants to perform additional fermentation assays on different types of must, i.e., Sauvignon Blanc and Gewurztraminer, as well as Prosecco must from another vineyard. Overall, the data indicated similar fermentative abilities for the yeast strains in each must type, as demonstrated by the overlapping kinetics and the comparable levels of ethanol produced by wild-type and mutant cells (data not shown). Importantly, as reported in Figure 8, yeast mutants produced lower levels of total and free SO2 than the wild-type cells in all must types, consistent with previous results, supporting that the effects of ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 double mutation occurred independently from the must/substrate used for the fermentation assays.

Figure 8.

Total and free SO2 production by winery yeast strains in different fermentation substrates. Parental (WT, blue bars) and double mutant (ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2, orange bars) cells of the indicated strains (STR, HIGH, MED, and LOW) have been used to perform fermentation assays in natural grape musts of different types (“Sauvignon”, Gewurztraminer”, and “Prosecco 2”). Diagrams report the final amounts of total (left panels) and free SO2 (right panels) produced by the yeast strains. Values are expressed as the mean ± S.D. (n = 2). * p-value < 0.05; ** p-value < 0.01, unpaired Student’s t-test.

Collectively, experimental evidence supported the conclusion that yeast strains carrying the inactivation of high affinity transporters Sul1p/Sul2p, thus reducing sulphate cellular availability, produced significantly lower levels of SO2 and acetaldehyde at the end of fermentation, while keeping unaltered their fermentative properties. The ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 mutation, however, did not modify the yeast’s ability to release the main secondary metabolites produced during fermentation, which are of crucial relevance for the sensory properties of the final wine. Moreover, data demonstrated that the effects of the modifications occurred in a similar way for all four yeast strains we tested, regardless of the genetic background, their intrinsic aptitudes (as SO2 producers), as well as the type of must used as a fermentation substrate, strongly suggesting that sulphate intake is the determining factor in SO2 production by yeast cells during the oenological fermentations.

In conclusion, the data support the hypothesis that during fermentation, the decrease of SO4-- transport into the cells leads to the reduction of SO2 production, irrespectively of both the fermentation substrate and yeast strain features, i.e., it is not related to strain-specific traits.

4. Discussion

Sulphur dioxide (SO2) is widely used in winemaking as an antimicrobial and antioxidant additive, but excessive levels may compromise the quality of the final product and could be potentially dangerous for human health [7]. Therefore, SO2 use is limited as much as possible, but future perspectives aim to further diminish the SO2 requirement in the production of wine, exploring the use of alternative chemical additives (e.g., ascorbic acid, GSH) [43,44] and the selection of low-SO2-producing yeast strains [27,30,45]. Nevertheless, biotechnology could help find the most effective way to modify the yeast properties while lowering the SO2 production during the fermentation process.

Very recently, it has been reported [31] that in the wine yeast strain EC1118, the specific inactivation of either Sul1p or Sul2p sulphate permeases resulted in a decrease of sulphur compounds (SO2 and H2S) produced by the yeast cells, revealing that SO4-- uptake and SO2 release appear directly correlated.

Here, we have thus investigated the effects on SO2 production in different wine yeast strains when sulphate uptake is drastically decreased by the complete elimination of the high-affinity transport system, mediated by Sul1p and Sul2p, i.e., deleting simultaneously the two corresponding genes.

Sul1p and Sul2p are closely related membrane proteins belonging to the sulphate permeases (SulP) family [46], which respectively consist of 859 and 893 residues, sharing high overall sequence similarity (>63% identity), with the presence of multiple (10–13) transmembrane α-helical regions [13]. In addition to sulphate transport activity, Sul1p and Sul2p have also been implicated as nutrient sensors linked to the activation of the TOR kinase pathway [14].

As an initial step, four different S. cerevisiae strains from a private collection, already characterised and commonly used in winemaking, have been selected on the basis of their intrinsic ability to produce SO2 and are thus representative of strains that may be classified as strong-, high-, medium-, or low-producers of SO2. All four strains have been genetically modified by the CRISPR/Cas9 system, successfully generating mutant strains carrying single and double deletions for either the SUL1 or SUL2 genes.

The functional characterisation of the mutant strains demonstrated that the effects of the genetic modifications, so far observed in laboratory yeast strains [9,13,16,29], are actually recapitulated in natural strains: the mutations (single or double) do not compromise the yeast viability in optimal conditions, whereas double mutant cells are sensitive to the environmental sulphate levels. Consistently, ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 double mutants were auxotrophic to methionine and displayed increased resistance to exposure to toxic SO4---analogues, strongly supporting the hypothesis that the high-affinity transport system was completely inactivated in yeast double mutant cells.

Then, the fermentation assays in natural media must demonstrate that either single or double inactivation of Sul1p and Sul2p do not alter the performance of the yeast strains, as clearly indicated by the fermentative kinetics of the mutant strains, which are superimposable on those of the parental (unmodified) yeast cells. Moreover, no significant differences were observed in the production of ethanol and numerous (>50) oenologically relevant metabolites, including volatile and non-volatile compounds, which have been detected by HPLC and GC-MS assays.

Importantly, data demonstrated that the specific inactivation of the SO4-- high affinity transporters significantly reduced the levels of SO2 and acetaldehyde produced by the yeast cells during the fermentation of natural must, even of different types/origins. According to [40], data supported a major role for Sul2p compared to Sul1p, as indicated by lower SO2 levels detected for ΔSUL2 single mutants of all four strains. Noteworthy, identical effects of either SUL1 or SUL2 gene inactivation were observed in yeast strains endowed with different intrinsic features (i.e., high/low SO2 producers), providing experimental evidence further supporting that sulphate assimilation and SO2 production are directly correlated in natural wine strains.

Collectively, the data indicate that the double ΔSUL1/ΔSUL2 deletion, like a “magic wand”, can transform any high-producing strain into a low-SO2 producer without compromising the fermentative performances or altering the levels of the main compounds released by yeast metabolism during fermentation. It remains, however, to establish the winemaking performance of the mutant strains in industrial conditions (i.e., cellars), i.e., to evaluate the organoleptic and aromatic properties of the final wine produced by the mutants with respect to the parental strains.

Improving strains to possess such properties may be of extreme interest to the wine industry, as it would allow for a reduction in the use of SO2 without compromising the quality of the wine. However, the use of GMO yeasts in oenology is strictly regulated, or not permitted, in different countries. Considering that in the EU the rules date back to 2001, when the techniques for yeast genetic modification were limited, it should be noted that after 20 years of huge technological progress, today we have tools (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9) that allow to modify very precisely the yeast genome, with the possibility of generating novel strains (cisgenic or transgenic) carrying specific traits of interest. In the production of wine, two additional aspects should be evaluated to promote the use of GMO yeast strains: first, the fermentation processes take place in the cellars, or rather confined and controlled structures, with little probability of GMO diffusion in the environment; and secondly, during post-fermentation steps, yeast cells are normally separated and excluded from the wine bottles and therefore do not reach the final consumer.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation9030280/s1, Figure S1: Plasmid maps; Figure S2: PCR analysis of SUL1 and SUL2 loci; Figure S3: Genotype analysis by PCR inter-delta assay; Table S1: Volatile compounds detected by GC-MS analysis; Table S2: Plasmids and primers; Table S3: Features of natural grape juices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.A. and R.L.; methodology, R.L., P.A., C.P. and M.B.; formal analysis, S.G., F.R., M.F. and M.B.; investigation, S.G., F.R. and M.B.; resources, P.A., M.F. and G.S.; data curation, S.G., F.R. and C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G., F.R., C.P., G.S. and R.L.; writing—review and editing, G.S., C.P. and R.L.; supervision, R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by institutional funding to R.L. from the University of Padova (DOR 2020-2022). S.G. and F.R. are PhD fellows of the Program “PON2014-2020 Research and Innovation” (MIUR).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Paolo Veneziano and Francesco Rusalen (EVER S.r.l., Italy) for their great enthusiasm and active support for the present study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Blouin, J. Le SO2 en Oenologie; Dunod: Paris, France, 2014; ISBN 978-2-10-071956-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ribereau-Gayon, P.; Dubourdieu, D.; Doneche, B.; Lonvaud, A. Handbook of Enology: The Microbiology of Wine and Vinifications; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Danilewicz, J.C. Review of reaction mechanisms of oxygen and proposed intermediate reaction products in wine: Central role of iron and copper. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2003, 54, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, L.F.; Sparks, A.H. Sulphite-binding power of wines and ciders. I. Equilibrium constants for the dissociation of carbonyl bisulphite compounds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1973, 24, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UE. The Maximum Sulphur Dioxide Content of Wines; Official Journal of the European Union, L149 Annex I B.; UE: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; pp. 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Komarnisky, L.A.; Christopherson, R.J.; Basu, T.K. Sulfur: Its clinical and toxicologic aspects. Nutrition 2003, 19, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vally, H.; Misso, N.L.A.; Madan, V. Clinical effects of sulphite additives. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2009, 39, 1643–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiegers, J.H.; Bartowsky, E.J.; Henschke, P.A.; Pretorius, I.S. Yeast and bacterial modulation of wine aroma and flavour. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2005, 11, 139–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Surdin-Kerjan, Y. Metabolism of sulfur amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1997, 61, 503–532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- González Hernández, G.; Hardisson de La Torre, A.; José Arias León, J. Boron, sulphate, chloride and phosphate contents in musts and wines of the Tacoronte-Acentejo D.O.C. region (Canary Islands). Food Chem. 1997, 60, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerine, M.A.; Berg, H.W.; Kunkee, R.E.; Ough, C.S.; Singleton, V.L.; Webb, A.D. The composition of grapes. In The Technology of Wine Making, 4th ed.; Company, A.P.: Westport, CT, USA, 1980; pp. 77–139. [Google Scholar]

- Leske, P.A.; Sas, A.N.; Coulter, A.D.; Stockley, C.S.; Lee, T.H. The composition of Australian grape juice: Chloride, sodium and sulfate ions. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 1997, 3, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherest, H.; Davidian, J.-C.; Thomas, D.; Benes, V.; Ansorge, W.; Surdin-Kerjan, Y. Molecular Characterization of Two High Affinity Sulfate Transporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1997, 145, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankipati, H.N.; Rubio-Texeira, M.; Castermans, D.; Diallinas, G.; Thevelein, J.M. Sul1 and Sul2 Sulfate Transceptors Signal to Protein Kinase A upon Exit of Sulfur Starvation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 10430–10446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.W.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Prosser, I.M.; Clarkson, D.T. Isolation of a cDNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae that encodes a high affinity sulphate transporter at the plasma membrane. Mol. Gen. Genet. MGG 1995, 247, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.; Kankipati, H.; De Graeve, S.; Van Zeebroeck, G.; Foulquié-Moreno, M.R.; Lindgreen, S.; Thevelein, J.M. Major sulfonate transporter Soa1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and considerable substrate diversity in its fungal family. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donalies, U.E.B.; Stahl, U. Increasing sulphite formation inSaccharomyces cerevisiae by overexpression ofMET14 andSSU1. Yeast 2002, 19, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiegers, J.H.; Pretorius, I.S. Modulation of volatile sulfur compounds by wine yeast. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 74, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-W.; Walker, M.E.; Fedrizzi, B.; Gardner, R.C.; Jiranek, V. Hydrogen sulfide and its roles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a winemaking context. FEMS Yeast Res. 2017, 17, fox058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschenbruch, R.; Bonish, P. Production of sulphite and sulphide by low-and high-sulphite forming wine yeasts. Arch. Microbiol. 1976, 107, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugliano, M.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Vidal, S.; Capone, D.; Siebert, T.; Dieval, J.-B.; Aagaard, O.; Waters, E.J. Evolution of 3-Mercaptohexanol, Hydrogen Sulfide, and Methyl Mercaptan during Bottle Storage of Sauvignon blanc Wines. Effect of Glutathione, Copper, Oxygen Exposure, and Closure-Derived Oxygen. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2564–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugliano, M.; Fedrizzi, B.; Siebert, T.; Travis, B.; Magno, F.; Versini, G.; Henschke, P.A. Effect of Nitrogen Supplementation and Saccharomyces Species on Hydrogen Sulfide and Other Volatile Sulfur Compounds in Shiraz Fermentation and Wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 4948–4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.-Q.; Pilone, G.J. An overview of formation and roles of acetaldehyde in winemaking with emphasis on microbiological implications. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2000, 35, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando, T.; Mouret, J.-R.; Humbert-Goffard, A.; Aguera, E.; Sablayrolles, J.-M.; Farines, V. Comprehensive study of the dynamic interaction between SO2 and acetaldehyde during alcoholic fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linderholm, A.; Dietzel, K.; Hirst, M.; Bisson, L.F. Identification of MET10—932 and Characterization as an Allele Reducing Hydrogen Sulfide Formation in Wine Strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 7699–7707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordente, A.G.; Heinrich, A.; Pretorius, I.S.; Swiegers, J.H. Isolation of sulfite reductase variants of a commercial wine yeast with significantly reduced hydrogen sulfide production. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009, 9, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarbati, A.; Canonico, L.; Comitini, F.; Ciani, M. Reduction of Sulfur Compounds through Genetic Improvement of Native Saccharomyces cerevisiae Useful for Organic and Sulfite-Free Wine. Foods 2020, 9, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezzetti, F.; De Vero, L.; Giudici, P. Evolved Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine strains with enhanced glutathione production obtained by an evolution-based strategy. FEMS Yeast Res. 2014, 14, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocki, R.; Tamás, M.J. How Saccharomyces cerevisiae copes with toxic metals and metalloids. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 925–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vero, L.; Solieri, L.; Giudici, P. Evolution-based strategy to generate non-genetically modified organisms Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains impaired in sulfate assimilation pathway. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 53, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, M.E.; Zhang, J.; Sumby, K.M.; Lee, A.; Houlès, A.; Li, S.; Jiranek, V. Sulfate transport mutants affect hydrogen sulfide and sulfite production during alcoholic fermentation. Yeast 2021, 38, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, A.; De Pascale, F.; Bianca, F.; Rossi, A.; Frizzarin, M.; De Bernardini, N.; Bosaro, M.; Baldisseri, A.; Antoniali, P.; Lopreiato, R.; et al. Large-scale sequencing and comparative analysis of oenological Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains supported by nanopore refinement of key genomes. Food Microbiol. 2021, 97, 103753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mans, R.; van Rossum, H.M.; Wijsman, M.; Backx, A.; Kuijpers, N.G.A.; van den Broek, M.; Daran-Lapujade, P.; Pronk, J.T.; van Maris, A.J.A.; Daran, J.M.G. CRISPR/Cas9: A molecular Swiss army knife for simultaneous introduction of multiple genetic modifications in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2015, 15, fov004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amberg, D.C.; Burke, D.; Strathern, J.N.; Burke, D.; Laboratory, C.S.H. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 0879697288 9780879697280. [Google Scholar]

- Vokes, M.; Carpenter, A. Using CellProfiler for Automatic Identification and Measurement of Biological Objects in Images. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2008, 82, 14.17.1–14.17.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gietz, R.D.; Woods, R.A. Yeast transformation by the LiAc/SS Carrier DNA/PEG method. Methods Mol. Biol. 2006, 313, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Legras, J.-L.; Karst, F. Optimisation of interdelta analysis for Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain characterisation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 221, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirisola, M.G.; Braun, R.J.; Petranovic, D. Approaches to study yeast cell aging and death. FEMS Yeast Res. 2014, 14, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iland, P.; Bruer, N.; Edwards, G.; Caloghiris, S.; Wilkes, E. Chemical Analysis of Grapes and Wine: Techniques and Concepts, 2nd ed.; Patrick Iland Wine Promotions Pty Ltd.: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2013; ISBN 0958160575. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Y.; Lagniel, G.; Godat, E.; Baudouin-Cornu, P.; Junot, C.; Labarre, J. Chromate Causes Sulfur Starvation in Yeast. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 106, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M.L.; Cui, J. Inactivation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sulfate Transporter Sul2p: Use It and Lose It. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackowetz, J.N.; Dierschke, S.; Mira de Orduña, R. Multifactorial analysis of acetaldehyde kinetics during alcoholic fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comuzzo, P.; Zironi, R. Biotechnological Strategies for Controlling Wine Oxidation. Food Eng. Rev. 2013, 5, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisanti, M.T.; Blaiotta, G.; Nioi, C.; Moio, L. Alternative Methods to SO2 for Microbiological Stabilization of Wine. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capece, A.; Pietrafesa, R.; Siesto, G.; Romano, P. Biotechnological Approach Based on Selected Saccharomyces cerevisiae Starters for Reducing the Use of Sulfur Dioxide in Wine. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piłsyk, S.; Paszewski, A. Sulfate permeases phylogenetic diversity of sulfate transport. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2009, 56, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).