Bioyogurt Enriched with Provitamin A Carotenoids and Fiber: Bioactive Properties and Stability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Bacterial Strains

2.3. Adequacy and Evaluation of Physicochemical Parameters of Carrot (Daucus carota) and Mango (Mangifera indica) Pulps

2.4. Production of Bioyogurt

2.5. Growth Kinetics of the Starter and Probiotic Cultures Under Fermentation Conditions

2.6. Viability of Probiotic and Starter Cultures During Refrigerated Storage

2.7. Evaluation of the Physicochemical Stability of Bioyogurt During Refrigerated Storage

2.8. Determination of Total Phenolic and Carotenoid Content in Bioyogurt During Refrigerated Storage

- •

- Content of total phenolics: Total phenolic content was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu spectrophotometric assay as described by [8], with modifications. A mixture was prepared containing 200 µL of yogurt extract, 800 µL of deionized water, and 100 µL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, which was incubated for 3 min at room temperature. Then, 300 µL of 20% sodium carbonate was added, and the mixture was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 2 h. Absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Jasco V-530, Hachioji, Japan). A blank sample was prepared using distilled water instead of the extract. A gallic acid standard curve (0–100 mg/L) was prepared, and total phenolic content was expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents per 100 g of the evaluated extract. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate, and the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

- •

- Content total carotenoids: the total carotenoid content was determined according to the methodology suggested by [29,30]. Each bioyogurt treatment (5 g) was saponified by mixing with 37.5 mL of methanol and 12.5 mL of 50% potassium hydroxide in a flask to release esterified carotenoids and remove chlorophylls and lipids. Unsaponifiable carotenoids were extracted with 20 mL of diethyl ether, washed twice with 40 mL of distilled water, and treated with anhydrous sodium sulfate. The solvent evaporated in a water bath, and the dry residue was dissolved in 20 mL of petroleum ether. The organic phase, containing carotenoids, was separated using a glass pipette. Total carotenoids were measured spectrophotometrically at 450 nm using 0.1% hexane as a blank, and concentrations were quantified using a β-carotene calibration curve. Results were expressed as milligrams of β-carotene equivalents per gram of bioyogurt. Each analysis was performed in duplicate under dark conditions.

2.9. Antioxidant Activity of Bioyogurt During Storage

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Carrot (Daucus carota) and Mango (Mangifera indica) Pulps

3.2. Growth Kinetics of the Starter and Probiotic Cultures Under Bioyogurt Fermentation Conditions

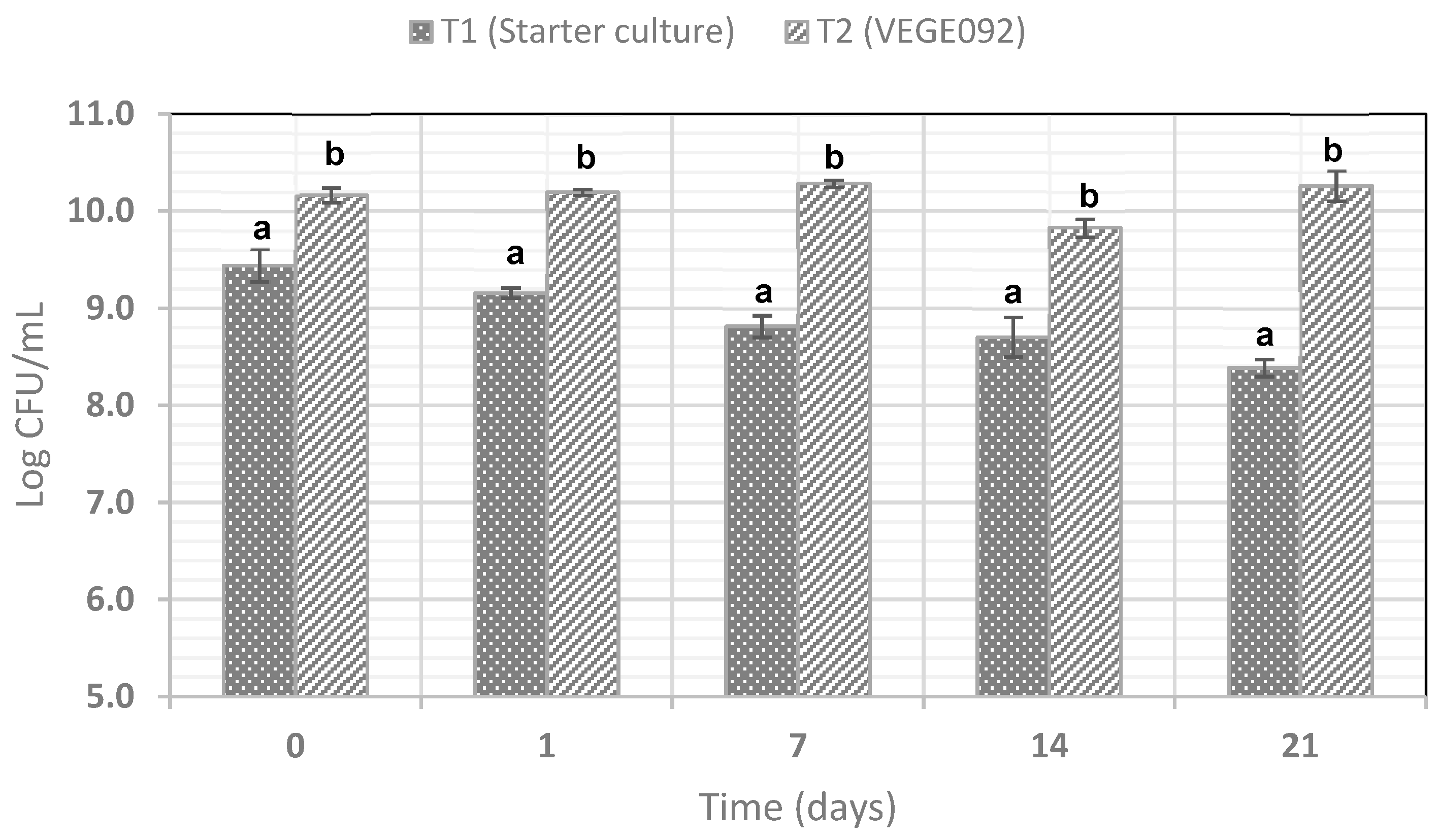

3.3. Viability of the Probiotic and Starter Cultures During Refrigerated Storage of Bioyogurt

3.4. Evaluation of the Physicochemical Characteristics of Bioyogurt During Refrigerated Storage

3.5. Determination of Total Phenolic Content, Carotenoids, and Antioxidant Activity of Bioyogurt During Refrigerated Storage

4. Discussion

4.1. Characterization of Carrot (Daucus carota) and Mango (Mangifera indica) Pulps

4.2. Growth Kinetics of Starter and Probiotic Cultures Under Bioyogurt Fermentation Conditions

4.3. Viability of the Probiotic and Starter Cultures During Refrigerated Storage of Bioyogurt

4.4. Evaluation of the Physicochemical Characteristics of Bioyogurt During Refrigerated Storage

4.5. Determination of Total Phenolic Content, Carotenoids, and Antioxidant Activity of Bioyogurt During Refrigerated Storage

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LAB | Lactic Acid Bacteria |

| FRAP | Ferric-Reducing Ability of Plasma |

| CFU | Colony Forming Units |

| MRS | Man, Rogosa and Sharpe |

References

- Patel, P.; Jethani, H.; Radha, C.; Vijayendra, S.; Mudliar, S.N.; Sarada, R.; Chauhan, V.S. Development of a carotenoid enriched probiotic yogurt from fresh biomass of Spirulina and its characterization. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 3721–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, T.N.; Nasser, S.A. Characterization of carotenoids double-encapsulated and incorporate in functional stirred yogurt. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 979252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Kamal, M.M.; Rahman, M.H.; Siddiqui, M.N.; Haque, M.A.; Saha, K.K.; Rahman, M.A. Functional dairy products as a source of bioactive peptides and probiotics: Current trends and future prospectives. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo-Herrera, Á.D.; Bernal-Castro, C.; Gutiérrez-Cortes, C.; Castro, C.N.; Díaz-Moreno, C. Bio-yogurt with the inclusion of phytochemicals from carrots (Daucus carota): A strategy in the design of functional dairy beverage with probiotics. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 2297–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.; Awad, S.; El-Sayed, I.; Ibrahim, A. Impact of chickpea as prebiotic, antioxidant and thickener agent of stirred bio-yoghurt. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2020, 65, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, W.; Suarez-Lepe, J.; Loira, I.; Palomero, F.; Morata, A. Dairy and nondairy-based beverages as a vehicle for probiotics, prebiotics, and symbiotics: Alternatives to health versus disease binomial approach through food. In Milk-Based Beverages; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 473–520. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Gao, C.; Han, X.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Lu, F. Co-fermentation of lentils using lactic acid bacteria and Bacillus subtilis natto increases functional and antioxidant components. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourghorban, S.; Yadegarian, L.; Jalili, M.; Rashidi, L. Comparative physicochemical, microbiological, antioxidant, and sensory properties of pre-and post-fermented yoghurt enriched with olive leaf and its extract. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldo, J.; Sendra, E. Recent Advances and Trends in the Dairy Field. Foods 2022, 11, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, R.; Liao, W.; Xie, J.; Chen, Y.; Peng, G.; Xie, J.; Sun, N.; Liu, S.; Yu, C.; Yu, Q. Enrichment of yogurt with carrot soluble dietary fiber prepared by three physical modified treatments: Microstructure, rheology and storage stability. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 75, 102901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Cliff, M. Carrot juice yogurts: Composition, microbiology, and sensory acceptance. In Yogurt in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 221–235. [Google Scholar]

- Guiné, R.P.; De Lemos, E.T. Development of new dairy products with functional ingredients. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2020, 18, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, S.; Rezessy-Szabó, J.M.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Hoschke, Á. Changes of microbial population and some components in carrot juice during fermentation with selected Bifidobacterium strains. Process Biochem. 2008, 43, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vénica, C.I.; Spotti, M.J.; Pavón, Y.L.; Molli, J.S.; Perotti, M.C. Influence of carrot fibre powder addition on rheological, microstructure and sensory characteristics of stirred-type yogurt. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 1916–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Martínez, E.; Gutiérrez-Cortés, C.; García-Mahecha, M.; Díaz-Moreno, C. Evaluation of viability of probiotic bacteria in mango (Mangifera indica L. Cv.“Tommy Atkins”) beverage. Dyna 2018, 85, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afiyah, D.; Sarbini, R.; Suryati, T. β-carotene content and quality properties of probiotic yoghurt supplemented with podang urang mango extract. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1020, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, F.J.; Nates-Parra, G.; Kondo, T. Mielato de Stigmacoccus asper (Hemiptera: Stigmacoccidae): Recurso melífero de bosques de roble en Colombia. Rev. Colomb. Entomol. 2013, 39, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Seraglio, S.K.T.; Silva, B.; Bergamo, G.; Brugnerotto, P.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Fett, R.; Costa, A.C.O. An overview of physicochemical characteristics and health-promoting properties of honeydew honey. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Plutino, M.; Lucini, L.; Aromolo, R.; Martinelli, E.; Souto, E.B.; Santini, A.; Pignatti, G. Bee products: A representation of biodiversity, sustainability, and health. Life 2021, 11, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theis, S. Authorised EU health claim for chicory inulin. In Foods, Nutrients and Food Ingredients with Authorised EU Health Claims; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Zhao, J. Commercial strains of lactic acid bacteria with health benefits. In Lactic Acid Bacteria: Omics and Functional Evaluation; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 297–369. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. AOAC, Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 20th ed.; AOAC International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McCleary, B.V. Modification to AOAC official methods 2009.01 and 2011.25 to allow for minor overestimation of low molecular weight soluble dietary fiber in samples containing starch. J. AOAC Int. 2014, 97, 896–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Prosky, L.; Vries, J.W.D. Determination of total, soluble, and insoluble dietary fiber in foods—Enzymatic-gravimetric method, MES-TRIS buffer: Collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 1992, 75, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Castro, C.A.; Díaz-Moreno, C.; Gutiérrez-Cortés, C. Inclusion of prebiotics on the viability of a commercial Lactobacillus casei subsp. rhamnosus culture in a tropical fruit beverage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filannino, P.; Cardinali, G.; Rizzello, C.G.; Buchin, S.; De Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R. Metabolic responses of Lactobacillus plantarum strains during fermentation and storage of vegetable and fruit juices. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2206–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhao, X.; Liu, C.; Li, T.; Mu, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Z. Fermentation characteristics and postacidification of yogurt by Streptococcus thermophilus CICC 6038 and Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus CICC 6047 at optimal inoculum ratio. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.-H.; Liu, F.; Luo, S.-Z.; Luo, J.-p. Pomegranate juice powder as sugar replacer enhanced quality and function of set yogurts: Structure, rheological property, antioxidant activity and in vitro bioaccessibility. LWT 2019, 115, 108479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiros, E.; Seifu, E.; Bultosa, G.; Solomon, W. Effect of carrot juice and stabilizer on the physicochemical and microbiological properties of yoghurt. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 69, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Bi, J.; Cao, F.; Ding, Y.; Peng, J. Effects of high pressure homogenization on physical stability and carotenoid degradation kinetics of carrot beverage during storage. J. Food Eng. 2019, 263, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, A.; Ghita, E.I.; El-Din, H.M.; Badran, S.M.; El-Messery, T. Evaluation yogurt fortified with vegetable and fruit juice as a natural sources of antioxidant. Int. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2015, 4, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, T.C.; de Oliveira, L.I.G.; Macedo, E.d.L.C.; Costa, G.N.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F.; Magnani, M. Understanding the potential of fruits, flowers, and ethnic beverages as valuable sources of techno-functional and probiotics strains: Current scenario and main challenges. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 25–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dardiry, A.I. Improving the properties of the functional frozen bio-yoghurt by using carrot pomace powder (daucus carota L.). Egypt. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bellis, P.; Sisto, A.; Lavermicocca, P. Probiotic bacteria and plant-based matrices: An association with improved health-promoting features. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 87, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siol, M.; Sadowska, A. Chemical composition, physicochemical and bioactive properties of avocado (Persea americana) seed and its potential use in functional food design. Agriculture 2023, 13, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purewal, S.S.; Verma, P.; Kaur, P.; Sandhu, K.S.; Singh, R.S.; Kaur, A.; Salar, R.K. A comparative study on proximate composition, mineral profile, bioactive compounds and antioxidant properties in diverse carrot (Daucus carota L.) flour. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 48, 102640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Abbeele, P.; Duysburgh, C.; Cleenwerck, I.; Albers, R.; Marzorati, M.; Mercenier, A. Consistent prebiotic effects of carrot RG-I on the gut microbiota of four human adult donors in the SHIME® model despite baseline individual variability. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Shah, C.; Mokashe, N.; Chavan, R.; Yadav, H.; Prajapati, J. Probiotics as potential antioxidants: A systematic review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 3615–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mahecha, M.; Soto-Valdez, H.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Madera-Santana, T.J.; Lomelí-Ramírez, M.G.; Colín-Chávez, C. Bioactive compounds in extracts from the agro-industrial waste of mango. Molecules 2023, 28, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolás García, M.; Borrás Enríquez, A.J.; González Escobar, J.L.; Calva Cruz, O.d.J.; Pérez Pérez, V.; Sánchez Becerril, M. Phenolic Compounds in Agro-Industrial Waste of Mango Fruit: Impact on Health and Prebiotic Effect—A Review. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2023, 73, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Pimentel-Moral, S.; Ochando-Pulido, J. New trends and perspectives in functional dairy-based beverages. Milk-Based Beverages 2019, 9, 95–138. [Google Scholar]

- Montemurro, M.; Pontonio, E.; Coda, R.; Rizzello, C.G. Plant-based alternatives to yogurt: State-of-the-art and perspectives of new biotechnological challenges. Foods 2021, 10, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Ye, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H. A comprehensive review of probiotic yogurt: Nutritional modulation, flavor improvement, health benefits, and advances in processing techniques. Agric. Prod. Process. Storage 2025, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangyu, M.; Muller, J.; Bolten, C.J.; Wittmann, C. Fermentation of plant-based milk alternatives for improved flavour and nutritional value. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 9263–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.W.; Aryana, K.J. Probiotic incorporation into yogurt and various novel yogurt-based products. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Yan, Q.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, S. Transcriptomic analysis of Pediococcus pentosaceus reveals carbohydrate metabolic dynamics under lactic acid stress. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 736411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Shi, Z.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Jiang, X.; Du, L.; Tu, M.; Zeng, X.; Wu, Z. Characterization of the effects of binary probiotics and wolfberry dietary fiber on the quality of yogurt. Food Chem. 2023, 406, 135020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swears, R.M.; Manley-Harris, M. Composition and potential as a prebiotic functional food of a Giant Willow Aphid (Tuberolachnus salignus) honeydew honey produced in New Zealand. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S. Activity of cecropin P1 and FA-LL-37 against urogenital microflora. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januário, J.; Da Silva, I.; De Oliveira, A.; De Oliveira, J.; Dionísio, J.; Klososki, S.; Pimentel, T. Probiotic yoghurt flavored with organic beet with carrot, cassava, sweet potato or corn juice: Physicochemical and texture evaluation, probiotic viability and acceptance. Int. Food Res. J. 2017, 24, 359–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel, H. 1.2. 3.1 scale insect honeydew as forage for honey production. World Crop Pests 1997, 7, 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Recklies, K.; Peukert, C.; Kölling-Speer, I.; Speer, K. Differentiation of honeydew honeys from blossom honeys and according to their botanical origin by electrical conductivity and phenolic and sugar spectra. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 1329–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.L.; Polemis, N.; Morales, V.; Corzo, N.; Drakoularakou, A.; Gibson, G.R.; Rastall, R.A. In vitro investigation into the potential prebiotic activity of honey oligosaccharides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2914–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, T.A.D.G.; de Oliveira, M.E.G.; Campos, M.I.F.; de Assis, P.O.A.; de Souza, E.L.; Madruga, M.S.; Pacheco, M.T.B.; Pintado, M.M.E.; do Egypto, R.d.C.R. Impact of honey on quality characteristics of goat yogurt containing probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus. LWT 2017, 80, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, L.A.; Alves, É.E.; Ribeiro, A.d.M.F.; Júnior, V.R.R.; Antunes, A.B.; dos Reis, A.F.; da Cruz Gomes, J.; de Carvalho, M.H.R.; Martinez, R.I.E. Viabilidade de bactérias probióticas em bioiogurte adicionado de mel de abelhas Jataí e africanizadas. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2018, 53, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovi, T.F.; Virgolin, L.B.; Janzantti, N.S.; Casarotti, S.N.; Penna, A.L.B. Fruit bioactive compounds: Effect on lactic acid bacteria and on intestinal microbiota. Food Res. Int. 2022, 161, 111809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, D.G.; Hammam, A.R.; El-Diin, M.A.N.; Awasti, N.; Abdel-Rahman, A.M. Nutritional, antioxidant, and antimicrobial assessment of carrot powder and its application as a functional ingredient in probiotic soft cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 1672–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.S.; Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Reimer, R.A.; Reid, G.; Verbeke, K.; Scott, K.P.; Holscher, H.D.; Azad, M.B.; Delzenne, N.M. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of synbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo-Rodrigues, H.; Santos, D.; Campos, D.A.; Guerreiro, S.; Ratinho, M.; Rodrigues, I.M.; Pintado, M.E. Impact of processing approach and storage time on bioactive and biological properties of rocket, spinach and watercress byproducts. Foods 2021, 10, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pulp | pH | Total Soluble Solids (°Brix) | Total Soluble Fiber (Dry Matter, g/100 g) | Total Carotenoids (µg β-Carotene/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carrot | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 11.0 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 0.09 | 6.5 ± 0.26 |

| Mango | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 10.5 ± 0.2 | 9.6 ± 0.14 | 6.1 ± 0.19 |

| pH | |||||

| Time (days) | |||||

| Treatment | 0 | 1 | 7 | 14 | 21 |

| T1 | 4.3 ± 0.01 a | 4.3 ± 0.02 a | 4.1 ± 0.04 a | 4.2 ± 0.02 a | 4.0 ± 0.02 a |

| T2 | 4.3 ± 0.0 a | 4.3 ± 0.03 a | 4.3 ± 0.01 a | 4.2 ± 0.01 a | 4.1 ± 0.05 a |

| Total soluble solids | |||||

| Time (days) | |||||

| Treatment | 0 | 1 | 7 | 14 | 21 |

| T1 | 16.1 ± 0.01 a | 15.6 ± 0.01 a | 13.1 ± 0.03 b | 11.3 ± 0.02 b | 10.0 ± 0.02 b |

| T2 | 16.3 ± 0.01 a | 15.5 ± 0.01 b | 16.1 ± 0.01 a | 16.3 ± 0.02 a | 16.3 ± 0.01 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernal-Castro, C.; Camargo-Herrera, Á.D.; Gutiérrez-Cortés, C.; Díaz-Moreno, C. Bioyogurt Enriched with Provitamin A Carotenoids and Fiber: Bioactive Properties and Stability. Fermentation 2025, 11, 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120698

Bernal-Castro C, Camargo-Herrera ÁD, Gutiérrez-Cortés C, Díaz-Moreno C. Bioyogurt Enriched with Provitamin A Carotenoids and Fiber: Bioactive Properties and Stability. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):698. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120698

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernal-Castro, Camila, Ángel David Camargo-Herrera, Carolina Gutiérrez-Cortés, and Consuelo Díaz-Moreno. 2025. "Bioyogurt Enriched with Provitamin A Carotenoids and Fiber: Bioactive Properties and Stability" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120698

APA StyleBernal-Castro, C., Camargo-Herrera, Á. D., Gutiérrez-Cortés, C., & Díaz-Moreno, C. (2025). Bioyogurt Enriched with Provitamin A Carotenoids and Fiber: Bioactive Properties and Stability. Fermentation, 11(12), 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120698