Enhanced In Vitro System for Predicting Methane Emissions from Ruminant Feed

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Care

2.2. In Vitro Incubation

2.3. Chemical Analysis and Measurements

2.4. Standardization

2.5. Effective Ruminal Methane Production Rate

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Evaluation of Effective Ruminal Methane Production Rate

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Standardization of In Vitro Fermentation Parameters of Feeds Using a Reference Diet

3.2. Ruminal Fermentation Paramters of the Tested Feeds

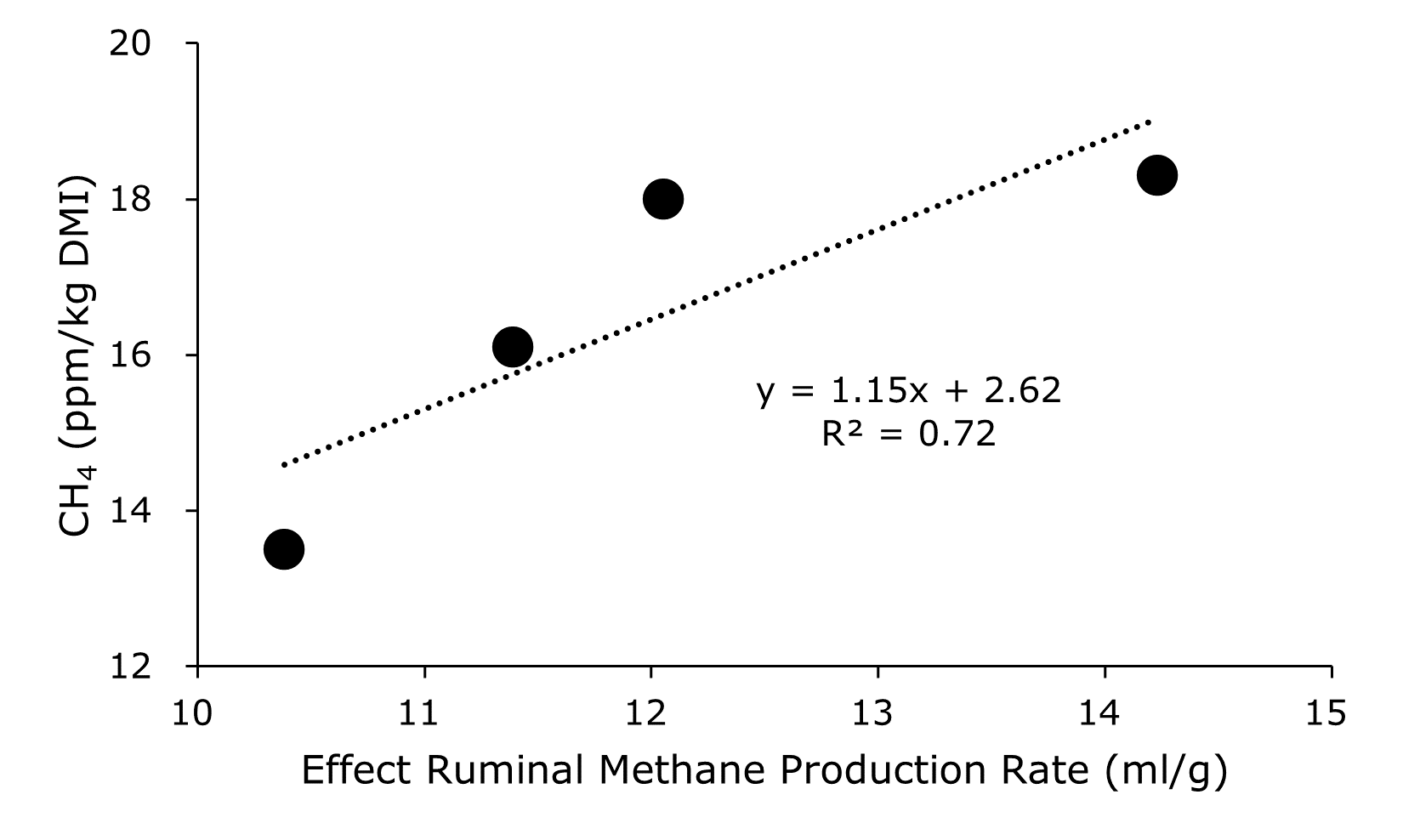

3.3. Determination and Application of Effective RUMINAL Methane Production Rate

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOAC | Association of Official Analytical Chemists |

| BW | Body weight |

| CH4 | Methane |

| CP | Crude protein |

| DDGS | Distiller’s grain with solubles |

| DM | Dry matter |

| eRMR | effective ruminal methane production rate |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| IVRF | In vitro ruminal fermentation |

| kd | Ruminal fractional rate of digestion |

| kp | Ruminal fractional rate of passage |

| NDF | Neutral detergent fiber |

| TDDM | True dry matter digestibility |

| Vmax | Asymptotic maximum gas production |

References

- Johnson, K.A.; Johnson, D.E. Methane emissions from cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2483–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lingen, H.J.; Niu, M.; Kebreab, E.; Valadares Filho, S.C.; Rooke, J.A.; Duthie, C.-A.; Schwarm, A.; Kreuzer, M.; Hynd, P.I.; Caetano, M.; et al. Prediction of enteric methane production, yield and intensity of beef cattle using an intercontinental database. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 283, 106575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, L.O.; Abdalla, A.L.; Álvarez, C.; Anuga, S.W.; Arango, J.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Becquet, P.; Berndt, A.; Burns, R.; De Camillis, C.; et al. Quantification of methane emitted by ruminants: A review of methods. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; McSweeney, C.; Wright, A.-D.G.; Bishop-Hurley, G.; Kalantar-zadeh, K. Measuring methane production from ruminants. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Bannink, A.; Dijkstra, J.; Kebreab, E.; Morgavi, D.P.; O’Kiely, P.; Reynolds, C.K.; Schwarm, A.; Shingfield, K.J.; Yu, Z.; et al. Design, implementation and interpretation of in vitro batch culture experiments to assess enteric methane mitigation in ruminants—A review. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2016, 216, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-N.; Lee, T.-T.; Yu, B. Improving the prediction of methane production determined by in vitro gas production technique for ruminants. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2016, 16, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Mamuad, L.L.; Jeong, C.-D.; Choi, Y.-J.; Lee, S.S.; Ko, J.-Y.; Lee, S.-S. In vitro evaluation of different feeds for their potential to generate methane and change methanogen diversity. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 26, 1698–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, S.C.; Kim, J.D.; Oh, Y.G.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, C.W.; Kim, K.J. Methane production potential of feed ingredients as measured by in vitro gas test. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2003, 16, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, S.L.; Roca-Fernández, A.I.; Rubano, M.D.; Soder, K.J. Evaluation of a single-flow continuous culture fermenter system for determination of ruminal fermentation and enteric methane production. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 103, 1313–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun, J.S.; Fellner, V.; Gumpertz, M.L. Methane production by mixed ruminal cultures incubated in dual-flow fermentors. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, R.; González, J.S.; López, S. Decrease of ruminal methane production in Rusitec fermenters through the addition of plant material from rhubarb (Rheum spp.) and alder buckthorn (Frangula alnus). J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 3755–3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramin, M.; Huhtanen, P. Development of an in vitro method for determination of methane production kinetics using a fully automated in vitro gas system—A modelling approach. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012, 174, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, R.; Ramin, M.; Bertilsson, J.; Lund, P.; Huhtanen, P. Evaluation of a gas in vitro system for predicting methane production in vivo. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 8881–8894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. Revision of In Vitro Rumen Fermentation Technique Using Rumen Fluid to Estimate Ruminal Fermentability of Carbohydrate-Based Feeds. Master's thesis, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Lee, M.; Jeon, S.; Seo, S. Evaluation of the associative effects of rice straw with timothy hay and corn grain using an in vitro ruminal gas production technique. Animals 2020, 10, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Sohn, K.-N.; Seo, S. Evaluation of feed value of a by-product of pickled radish for ruminants: Analyses of nutrient composition, storage stability, and in vitro ruminal fermentation. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2016, 58, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goering, H.K.; Van Soest, P.J. Forage Fiber Analyses (Apparatus, Reagents, Procedures, and Some Applications); U.S. Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1970.

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licitra, G.; Hernandez, T.M.; Van Soest, P.J. Standardization of procedures for nitrogen fractionation of ruminant feeds. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1996, 57, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.B.; Hoover, W.H.; Jennings, J.P.; Webster, T.K.M. A method for partitioning neutral detergent-soluble carbohydrates. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1999, 79, 2079–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.B. Determination of starch, including maltooligosaccharides, in animal feeds: Comparison of methods and a method recommended for AOAC collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 2009, 92, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 7th ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pell, A.N.; Schofield, P. Computerized monitoring of gas production to measure forage digestion in vitro. J. Dairy Sci. 1993, 76, 1063–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffrenato, E.; Nicholson, C.F.; Van Amburgh, M.E. Development of a mathematical model to predict pool sizes and rates of digestion of 2 pools of digestible neutral detergent fiber and an undigested neutral detergent fiber fraction within various forages. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goeser, J.P.; Combs, D.K. An alternative method to assess 24-h ruminal in vitro neutral detergent fiber digestibility. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 3833–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, P.H.; Givens, D.I.; Getachew, G. Evaluation of NRC, UC Davis and ADAS approaches to estimate the metabolizable energy values of feeds at maintenance energy intake from equations utilizing chemical assays and in vitro determinations. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2004, 114, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, P.; Pitt, R.E.; Pell, A.N. Kinetics of fiber digestion from in vitro gas production. J. Anim. Sci. 1994, 72, 2980–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Lanzas, C.; Schwab, C.G.; Fox, D.G. Development and evaluation of empirical equations to predict feed passage rate in cattle. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2006, 128, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Kang, K.; Kang, H.; Jeon, S.; Lee, M.; Park, E.; Hong, S.; Seo, S. Repeatability of feed efficiency and its relationship with carcass traits in Hanwoo steers during their entire growing and fattening period. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Soetaert, K.; Petzoldt, T.; Setzer, R.W. Solving differential equations in R: Package deSolve. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 33, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Cho, H.; Jeong, S.; Jeon, S.; Lee, M.; Lee, S.; Baek, Y.; Oh, J.; Seo, S. Application of a hand-held laser methane detector for measuring enteric methane emissions from cattle in intensive farming. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Cho, H.; Jeong, S.; Kang, K.; Lee, M.; Jeon, S.; Kang, H.; Seo, S. Effects of dietary crude protein level of concentrate mix on growth performance, rumen characteristics, blood metabolites, and methane emissions in fattening Hanwoo steers. Animals 2024, 14, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchini, N.D.; Broderick, G.A.; Combs, D.K. In vitro determination of ruminal protein degradation using freeze-stored ruminal microorganisms. J. Anim. Sci. 1996, 74, 2488–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Iowerth, D.; Jones, H.; Hayward, M.V. The effect of pepsin pretreatment of herbage on the prediction of dry matter digestibility from solubility in fungal cellulase solutions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1975, 26, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeser, J.P.; Hoffman, P.C.; Combs, D.K. Modification of a rumen fluid priming technique for measuring in vitro neutral detergent fiber digestibility. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 3842–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabro, C.; Sarnataro, C.; Spanghero, M. Impacts of rumen fluid, refrigerated or reconstituted from a refrigerated pellet, on gas production measured at 24h of fermentation. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 268, 114585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunkala, B.Z.; DiGiacomo, K.; Alvarez Hess, P.S.; Dunshea, F.R.; Leury, B.J. Rumen fluid preservation for in vitro gas production systems. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2022, 292, 115405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Yu, Z. Aerobic cultivation of anaerobic rumen protozoa, Entodinium caudatum and Epidinium caudatum. J. Microbiol. Methods 2018, 152, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunkala, B.Z.; DiGiacomo, K.; Alvarez Hess, P.S.; Dunshea, F.R.; Leury, B.J. Impact of rumen fluid storage on in vitro feed fermentation characteristics. Fermentation 2023, 9, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mould, F.L.; Ørskov, E.R.; Mann, S.O. Associative effects of mixed feeds. I. effects of type and level of supplementation and the influence of the rumen fluid pH on cellulolysis in vivo and dry matter digestion of various roughages. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1983, 10, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.F.; Wu, Y.M.; Liu, J.X. In vitro gas production technique to evaluate associative effects among lucerne hay, rice straw and maize silage. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2007, 16, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.B.; Pell, A.N.; Chase, L.E. Characteristics of neutral detergent-soluble fiber fermentation by mixed ruminal microbes. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1998, 70, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Lee, S.C.; Lee, S.Y.; Seo, J.G.; Ha, J.K. Degradation kinetics of carbohydrate fractions of ruminant feeds using automated gas production technique. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 22, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, G.; Robinson, P.H.; DePeters, E.J.; Taylor, S.J. Relationships between chemical composition, dry matter degradation and in vitro gas production of several ruminant feeds. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2004, 111, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, G.; DePeters, E.J.; Robinson, P.H.; Fadel, J.G. Use of an in vitro rumen gas production technique to evaluate microbial fermentation of ruminant feeds and its impact on fermentation products. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2005, 123–124, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J. Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, G.B. Starch utilization by ruminants: From basics to the bunk. J. Anim. Sci. 1997, 75, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, W.H.; Lambeth, C.; Theurer, B.; Ray, D.E. Digestibility and utilization of cottonseed hulls by cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1969, 29, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mara, F.P.; Mulligan, F.J.; Cronin, E.J.; Rath, M.; Caffrey, P.J. The nutritive value of palm kernel meal measured in vivo and using rumen fluid and enzymatic techniques. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1999, 60, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgavi, D.P.; Forano, E.; Martin, C.; Newbold, C.J. Microbial ecosystem and methanogenesis in ruminants. Animal 2010, 4, 1024–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidot, M.; Sarnataro, C.; Romanzin, A.; Spanghero, M. A new equipment for continuous measurement of methane production in a batch in vitro rumen system. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 107, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, N.; Kim, J.; Seo, S. Comparison of models for estimating methane emission factor for enteric fermentation of growing-finishing Hanwoo steers. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Kebreab, E.; Hristov, A.N.; Oh, J.; Arndt, C.; Bannink, A.; Bayat, A.R.; Brito, A.F.; Boland, T.; Casper, D.; et al. Prediction of enteric methane production, yield, and intensity in dairy cattle using an intercontinental database. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 3368–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, J.W.; van Gelder, A.H.; Visscher, G.J.W.; Oudshoorn, L. Influence of rumen fluid and substrate concentration on fermentation kinetics measured with a fully automated time related gas production apparatus. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1996, 61, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Cho, H.; Kang, N.; Lee, M.; Hoque, M.R.; Kim, Y.Y.; Seo, S. Effects of dietary crude protein levels on growth performance, rumen characteristics, blood metabolites, and methane emissions in finishing Hanwoo steers. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 38, 1934–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristov, A.N. Invited review: Advances in nutrition and feed additives to mitigate enteric methane emissions. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 4129–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, A.N.; Oh, J.; Firkins, J.L.; Dijkstra, J.; Kebreab, E.; Waghorn, G.; Makkar, H.P.; Adesogan, A.T.; Yang, W.; Lee, C.; et al. Special topics--Mitigation of methane and nitrous oxide emissions from animal operations: I. A review of enteric methane mitigation options. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 5045–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fant, P.; Ramin, M. Relationship between predicted in vivo and observed in vivo methane production from dairy cows fed a grass-silage based diet with barley, oats, or dehulled oats as a concentrate supplement. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2024, 311, 115955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item 1 | Corn Grain | Flaked Corn | Wheat Grain | Tapioca | Lupin | Soybean Meal | Canola Meal | Copra Meal | Palm Kernel Meal |

| DM, g/kg as fed | 849 | 858 | 891 | 894 | 905 | 900 | 904 | 905 | 916 |

| OM | 984 | 980 | 977 | 918 | 963 | 928 | 904 | 923 | 951 |

| CP | 90 | 86 | 129 | 34 | 308 | 531 | 415 | 245 | 184 |

| SOLP | 30 | 8 | 32 | 2 | 260 | 89 | 156 | 30 | 45 |

| NDICP | 4 | 10 | 9 | 18 | 8 | 13 | 17 | 135 | 123 |

| ADICP | 2 | 9 | 4 | 12 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 18 | 46 |

| Crude fiber | 15 | 25 | 24 | 201 | 168 | 60 | 115 | 165 | 220 |

| aNDF | 85 | 120 | 123 | 290 | 281 | 100 | 267 | 603 | 701 |

| ADF | 27 | 55 | 31 | 190 | 198 | 55 | 177 | 301 | 483 |

| ADL | 15 | 28 | 14 | 71 | 23 | 11 | 73 | 73 | 134 |

| Starch | 719 | 713 | 653 | 398 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Ether extract | 43 | 45 | 12 | 18 | 55 | 21 | 13 | 19 | 67 |

| Ash | 16 | 20 | 23 | 82 | 37 | 72 | 96 | 77 | 49 |

| TDN, % DM | 88.3 | 85.1 | 82.7 | 65.0 | 81.0 | 81.0 | 64.3 | 58.6 | 55.1 |

| ME, MJ/kg | 12.2 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 9.3 | 12.6 | 13.8 | 11.4 | 9.9 | 8.8 |

| NEm, MJ/kg | 9.0 | 8.6 | 8.5 | 5.9 | 9.0 | 9.8 | 7.4 | 5.9 | 5.1 |

| NEg, MJ/kg | 6.1 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 3.4 | 6.1 | 6.9 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 2.8 |

| NEl, MJ/kg | 7.8 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 5.7 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 7.2 | 6.2 | 5.4 |

| Carbohydrate | 850 | 849 | 836 | 866 | 600 | 376 | 476 | 660 | 700 |

| NFC | 770 | 741 | 722 | 594 | 327 | 290 | 226 | 192 | 123 |

| Item 1 | DDGS | Corn Gluten Feed | Soybean Hull | Cotton Seed Hull | Rice Bran | Wheat Bran | Beet Pulp | Timothy Hay | Annual Ryegrass Straw |

| DM, g/kg as fed | 908 | 929 | 894 | 913 | 910 | 906 | 920 | 920 | 898 |

| OM | 934 | 912 | 948 | 947 | 897 | 937 | 961 | 911 | 957 |

| CP | 294 | 230 | 110 | 74 | 149 | 183 | 98 | 100 | 47 |

| SOLP | 60 | 168 | 28 | 18 | 57 | 40 | 6 | 50 | 14 |

| NDICP | 33 | 16 | 45 | 30 | 20 | 67 | 40 | 10 | 12 |

| ADICP | 27 | 4 | 11 | 24 | 8 | 9 | 18 | 6 | 1 |

| Crude fiber | 84 | 97 | 384 | 436 | 104 | 92 | 228 | 413 | 440 |

| aNDF | 388 | 405 | 739 | 702 | 254 | 435 | 493 | 679 | 785 |

| ADF | 188 | 124 | 507 | 557 | 135 | 123 | 270 | 440 | 503 |

| ADL | 18 | 16 | 22 | 166 | 56 | 39 | 33 | 51 | 84 |

| Starch | 30 | 98 | 2 | 11 | 210 | 243 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Ether extract | 90 | 30 | 18 | 19 | 152 | 31 | 11 | 18 | 11 |

| Ash | 66 | 88 | 52 | 53 | 103 | 63 | 39 | 89 | 43 |

| TDN, % DM | 80.2 | 70.8 | 63.1 | 42.3 | 83.2 | 69.5 | 67.5 | 54.4 | 50.0 |

| ME, MJ/kg | 12.4 | 11.0 | 9.5 | 6.0 | 11.9 | 10.6 | 9.9 | 8.3 | 7.2 |

| NEm, MJ/kg | 8.8 | 7.4 | 5.9 | 2.9 | 8.6 | 7.1 | 6.4 | 4.7 | 3.9 |

| NEg, MJ/kg | 6.0 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 5.8 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| NEl, MJ/kg | 7.9 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 3.4 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 5.0 | 4.3 |

| Carbohydrate | 551 | 653 | 820 | 854 | 596 | 723 | 852 | 793 | 899 |

| NFC | 196 | 264 | 126 | 182 | 363 | 355 | 400 | 124 | 126 |

| Item | Incubation Time | Mean | SD | CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total gas production (mL/100 mg DM) | 2 | 3.13 | 0.52 | 0.166 |

| 4 | 6.13 | 0.84 | 0.138 | |

| 6 | 9.70 | 1.02 | 0.105 | |

| 24 | 21.44 | 1.10 | 0.051 | |

| Methane production (mL/100 mg DM) | 2 | 0.40 | 0.11 | 0.268 |

| 4 | 0.92 | 0.24 | 0.260 | |

| 6 | 1.50 | 0.33 | 0.220 | |

| 24 | 3.94 | 0.57 | 0.146 | |

| Methane production (mL/g true digested DM) | 6 | 27.39 | 5.86 | 0.214 |

| 24 | 52.20 | 7.35 | 0.141 | |

| True dry matter digestibility (%) | 6 | 56.12 | 4.58 | 0.082 |

| 24 | 75.71 | 4.04 | 0.053 |

| Feed | Batches | Total Gas Production | 24 h True DM Digestibility, g/kg | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vmax, mL/100 mg DM | kd, h−1 | Lag, h | |||

| Reference diet † | 29 ‡ | 24.3 ± 0.00 | 0.092 ± 0.0001 | 0.59 ± 0.002 | 756 ± 0.6 |

| Corn grain | 5 | 35.8 ± 2.15 | 0.086 ± 0.0062 | 1.11 ± 0.267 | 974 ± 50.7 |

| Flaked corn grain | 5 | 35.1 ± 3.45 | 0.097 ± 0.0138 | 1.05 ± 0.246 | 921 ± 117.0 |

| Wheat grain | 3 | 31.4 ± 1.10 | 0.167 ± 0.0175 | 1.10 ± 0.140 | 999 ± 58.6 |

| Tapioca | 5 | 26.8 ± 1.45 | 0.184 ± 0.0102 | 0.94 ± 0.306 | 823 ± 128.4 |

| Lupin | 3 | 25.2 ± 1.98 | 0.147 ± 0.0566 | 0.65 ± 0.534 | 937 ± 11.4 |

| Soybean meal | 2 | 21.5 ± 0.15 | 0.153 ± 0.0152 | 0.32 ± 0.354 | 937 ± 66.5 |

| Canola meal | 6 | 16.7 ± 1.00 | 0.147 ± 0.0282 | 0.26 ± 0.187 | 843 ± 47.7 |

| Copra meal | 5 | 23.6 ± 1.57 | 0.192 ± 0.0366 | 0.63 ± 0.213 | 859 ± 149.9 |

| Palm kernel meal | 4 | 19.8 ± 0.82 | 0.102 ± 0.0354 | 0.28 ± 0.289 | 590 ± 28.3 |

| DDGS | 3 | 18.2 ± 1.42 | 0.121 ± 0.0090 | 0.05 ± 0.087 | 810 ± 85.0 |

| Corn gluten feed | 6 | 25.0 ± 2.57 | 0.087 ± 0.0230 | 0.14 ± 0.185 | 882 ± 89.5 |

| Soybean hull | 5 | 64.7 ± 35.77 | 0.064 ± 0.0799 | 0.26 ± 0.581 | 828 ± 116.7 |

| Cotton seed hull | 4 | 17.0 ± 6.68 | 0.091 ± 0.0641 | 0.19 ± 0.370 | 450 ± 16.7 |

| Rice bran | 2 | 13.0 ± 4.45 | 0.225 ± 0.0024 | 0.96 ± 0.205 | 651 ± 99.0 |

| Wheat bran | 4 | 23.9 ± 0.95 | 0.144 ± 0.0164 | 0.72 ± 0.030 | 767 ± 41.0 |

| Beet pulp | 3 | 30.6 ± 1.38 | 0.139 ± 0.0025 | 1.01 ± 0.233 | 838 ± 60.4 |

| Timothy hay | 1 | 21.2 | 0.071 | 0.00 | 565 |

| Annual ryegrass | 4 | 15.0 ± 5.55 | 0.060 ± 0.0333 | 0.00 ± 0.000 | 441 ± 88.7 |

| Feed | Methane Production (mL/g of True Digested Dry Matter) | Effective Ruminal Methane Production Rate (mL/g Dry Matter) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 h | 24 h | ||

| Reference diet † | 27.46 ± 0.108 | 39.82 ± 0.088 | 14.82 ± 0.068 |

| Corn grain | 28.36 ± 3.433 | 38.11 ± 5.133 | 1.74 ± 0.537 |

| Flaked corn grain | 33.51 ± 6.593 | 46.63 ± 9.700 | 2.06 ± 0.493 |

| Wheat grain | 29.37 ± 2.497 | 41.81 ± 6.130 | 3.23 ± 0.473 |

| Tapioca | 35.46 ± 10.244 | 44.26 ± 5.771 | 12.42 ± 6.018 |

| Lupin | 30.13 ± 2.073 | 40.74 ± 4.368 | 15.80 ± 1.947 |

| Soybean meal | 18.78 ± 5.834 | 35.05 ± 6.124 | 1.15 ± 0.495 |

| Canola meal | 18.87 ± 3.599 | 25.07 ± 9.562 | 4.98 ± 1.495 |

| Copra meal | 39.28 ± 2.412 | 47.05 ± 9.427 | 31.02 ± 6.74 |

| Palm kernel meal | 32.44 ± 6.884 | 44.89 ± 10.144 | 20.65 ± 4.735 |

| DDGS | 18.40 ± 2.552 | 24.94 ± 3.477 | 6.70 ± 1.082 |

| Corn gluten feed | 17.30 ± 6.711 | 26.63 ± 15.117 | 9.15 ± 3.272 |

| Soybean hull | 19.28 ± 26.286 | 40.93 ± 9.838 | 56.74 ± 27.688 |

| Cotton seed hull | 13.61 ± 11.254 | 28.51 ± 8.955 | 12.10 ± 8.492 |

| Rice bran | 13.25 ± 1.655 | 18.37 ± 0.580 | 2.30 ± 0.283 |

| Wheat bran | 39.16 ± 6.247 | 48.86 ± 5.034 | 22.88 ± 2.347 |

| Beet pulp | 35.41 ± 9.105 | 46.42 ± 6.883 | 24.13 ± 5.024 |

| Timothy hay | 17.49 | 30.54 | 16.10 |

| Annual ryegrass | 12.18 ± 8.164 | 33.22 ± 6.737 | 20.13 ± 8.295 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seo, S.; Lee, M. Enhanced In Vitro System for Predicting Methane Emissions from Ruminant Feed. Fermentation 2025, 11, 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120681

Seo S, Lee M. Enhanced In Vitro System for Predicting Methane Emissions from Ruminant Feed. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):681. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120681

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeo, Seongwon, and Mingyung Lee. 2025. "Enhanced In Vitro System for Predicting Methane Emissions from Ruminant Feed" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120681

APA StyleSeo, S., & Lee, M. (2025). Enhanced In Vitro System for Predicting Methane Emissions from Ruminant Feed. Fermentation, 11(12), 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120681