Abstract

The interaction between the ship hull and the propeller’s rotational motion causes the propeller to operate under non-uniform inflow conditions. In reality, the ship’s effective wake constitutes a complex nonlinear superposition of multiple wave numbers. However, existing studies often neglect these multi-scale interactions. In this work, Unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (URANS) simulations with a two-scale inflow model are conducted to investigate the fluid–structure interaction of a propeller under multi-scale inflow. The model introduces large-scale and small-scale Fourier modes together with transverse perturbations, allowing systematic variation of inflow characteristics. The results reveal that large-scale modes amplify unsteady thrust fluctuations and enhance vortex fragmentation, while small-scale modes produce similar but weaker effects, mainly influencing the high-frequency components of unsteady thrust. In contrast, transverse perturbations reduce inflow non-uniformity, effectively suppress single blade thrust fluctuations, and preserve the coherent vortex structures of the wake. This study highlights the importance of multi-scale effects in the unsteady hydrodynamic characteristics of marine propellers and provides useful insights for the optimization of propeller design and energy-saving devices.

1. Introduction

The propeller is the most commonly used propulsion device in marine engineering, converting the engine’s rotational power into thrust [1]. Its hydrodynamic performance is directly related to a ship’s propulsion power, energy efficiency, and navigational safety [2]. In practical conditions, propellers operate within a complex, non-uniform inflow field. The non-uniformity mainly arises from the growth of the hull boundary layer, the blockage and turbulence generated by upstream structures, and the interaction between the propeller and the hull [3], which is characterized by both spatial non-uniformity and temporal unsteadiness [4,5]. Such conditions lead to periodic pressure fluctuations on the blade surfaces [4,5], resulting in unsteady hydrodynamic forces [6,7,8] that adversely affect propulsion efficiency [9,10,11], induce vibrations [12,13], and increase noise emissions [14,15]. Vibrations of the propeller can be transmitted through the shafting system, further exciting structural vibrations of the hull [16]. The periodic unsteady hydrodynamic pressures generate distinct tonal components at blade passing frequencies, forming a major contributor to propeller noise [17]. Furthermore, the deformation of elastic propellers under non-uniform inflow has been shown to differ by approximately 14% compared to uniform inflow conditions [18]. Therefore, investigating propeller performance under non-uniform inflow is essential for design optimization and operational improvement [19].

From a numerical simulation perspective, the implementation methods for non-uniform inflow fields primarily fall into two categories: integrated ship-propeller computational methods and non-uniform inflow conditions imposed at the inlet boundary. The integrated ship-propeller approach, which simulates the hull and propeller as a single entity, allows for the analysis of the propeller operating within the ship’s effective wake field. Jiang et al. [20] used the integrated approach to simulate the submarine model fitted with its propeller, assessing the propeller’s excitation forces at the self-propulsion point. Wei et al. [11] used a coupled model to analyze the hull–propeller–appendages interaction and its influence on the propeller’s hydrodynamic performance. More recently, Zhang et al. [21] used this method to investigate how a moonpool modifies the effective wake field, thereby affecting the propeller’s propulsion performance. While the integrated ship-propeller method provides a comprehensive representation of the non-uniform inflow field, it suffers from high computational costs and limited flexibility for parametric studies.

Alternatively, the non-uniform wake can be simulated by imposing prescribed inflow conditions at the inlet boundary, either by prescribing spatially varying velocity profiles or by generating turbulent inflow conditions.

The spatially varying velocity profiles are usually using nominal wake fields or periodic inflow fields. Nominal wake fields are obtained in a towing tank by measuring the time-averaged velocity distribution behind a ship hull without a propeller installed. He et al. [22] used the nominal wake as an inlet condition to study the unsteady loads and noise characteristics of a propeller in non-uniform inflow. Similarly, Liu et al. [6] used the nominal wake of a ship hull model to investigate the evolution of propeller wake vortex structures. However, such an inflow condition is overly idealized, as it depends on specific hull geometries and neglects the reproduction of periodic disturbances arising from the interaction between the ship wake and propeller rotation.

The periodic inflow field data are typically generated in experiments using metallic wire meshes, known as wake screens, to produce controlled inflow disturbances with prescribed spatial periodicity. The resulting unsteady velocity fields are measured using a Laser Doppler Velocimeter (LDV), and subsequently decomposed into Fourier series to reconstruct the periodic wake characteristics in simulations [12,23,24,25]. Tian et al. [12] used wake screens to generate the four-cycle and six-cycle inflows to study the blade vibratory strain, and Meng et al. [16] assessed the influence of different periodic wakes on propeller hydrodynamic excitation.

The last approach is to impose turbulent inflow conditions. Yao et al. [26] used a turbulence grid and a Fourier synthesis method to produce incoming turbulence to study the propeller’s unsteady forces and broadband spectral features. Wang et al. [19,27] used the synthetic eddy method to model turbulent inflow, examining its effects on the propeller’s transient loads and wake instabilities under varying turbulence intensities.

In reality, a ship’s effective wake is a complex, nonlinear superposition of multiple disturbance scales. However, existing inflow modeling approaches such as nominal wake, periodic inflow fields, and turbulent inflow have not yet been able to explicitly distinguish or quantify how disturbances of different scales influence the propeller’s unsteady hydrodynamic characteristics. Moreover, most of these studies have primarily focused on axial inflows, with limited attention to the role of transverse disturbances and their interaction with axial perturbations.

Zhao et al. [28] proposed a simplified two-scale wake model inspired by grid turbulence. Building on the recent theoretical advances by Zhao et al. [28] and Shao et al. [29], the two-scale wake model has been demonstrated to be the simplest possible flow configuration capable of sustaining nonlinear triadic interactions and reproducing both rapid and large-scale non-equilibrium dissipation behaviors. Unlike conventional grid-generated or synthetic turbulence models that contain a continuum of interacting modes, this minimal model retains only two characteristic perturbation scales, allowing a controllable separation of time scales and avoiding asynchronous multi-scale coupling. Its simplicity allows a clear interpretation of energy transfer and wake evolution while preserving the essential physics of multi-scale turbulence, providing a practical framework for analyzing how multi-scale interactions influence the propeller’s unsteady characteristics and wake dynamics.

In this study, Unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (URANS) simulations are performed to analyze the fluid–structure interaction of a propeller operating under a two-scale inflow field. The objective is to investigate how multi-scale inflow perturbations influence the propeller’s unsteady hydrodynamic characteristics and wake evolution. By varying the large-scale Fourier mode amplitude b, small-scale Fourier mode amplitude c, and transverse perturbation amplitude d, the unsteady hydrodynamic responses, vortex structures, and the evolution of the velocity and vorticity fields are systematically examined.

2. Mathematical and Numerical Model

In this study, the flow is assumed to be incompressible. For incompressible fluids, the governing equations of URANS [30] are expressed as

where ; t is the time; is the spatial coordinate; and are the mean and turbulent components of velocity, respectively; is the Reynolds stress components; is the fluid density; P is the mean pressure; and is the dynamic viscosity.

However, as the Reynolds stress tensor is an unknown term, the statistical mean equations are unclosed, necessitating turbulence modeling. Most of these turbulence models rely on the Boussinesq eddy viscosity hypothesis, expressed as

where is turbulent eddy viscosity; k is the turbulent kinetic energy; and is the Kronecker delta.

The SST model was chosen in the present study. Its blending function achieves a smooth transition between the near-wall and free shear flow regions. The governing equations [31] for turbulent kinetic energy k, specific dissipation rate , and turbulent kinematic viscosity are expressed as

where , are blending functions; is the turbulence production term; S is the invariant measure of the strain rate; and and are constants.

The computations were carried out in OpenFOAM [32] using the PIMPLE algorithm to solve the transient incompressible flow. Second-order upwind and second-order implicit backward schemes were used for spatial and temporal discretization, respectively, with the maximum Courant number kept below 2. A wall function approach is applied with to resolve the near-wall flow [33].

3. Setup of Numerical Simulation

3.1. Propeller Geometry

The propeller model used in the simulation is DTRC4119, designed by the David Taylor Research Center. The blades adopt modified NACA 66 sections, with zero skew and rake. The propeller model is shown in Figure 1, and the geometric parameters [24] are shown in Table 1, where r is the radial location and R is the radius of the propeller.

Figure 1.

DTRC 4119 propeller model.

Table 1.

Geometric parameters of DTRC4119 propeller.

3.2. Computational Domain and Boundary Condition

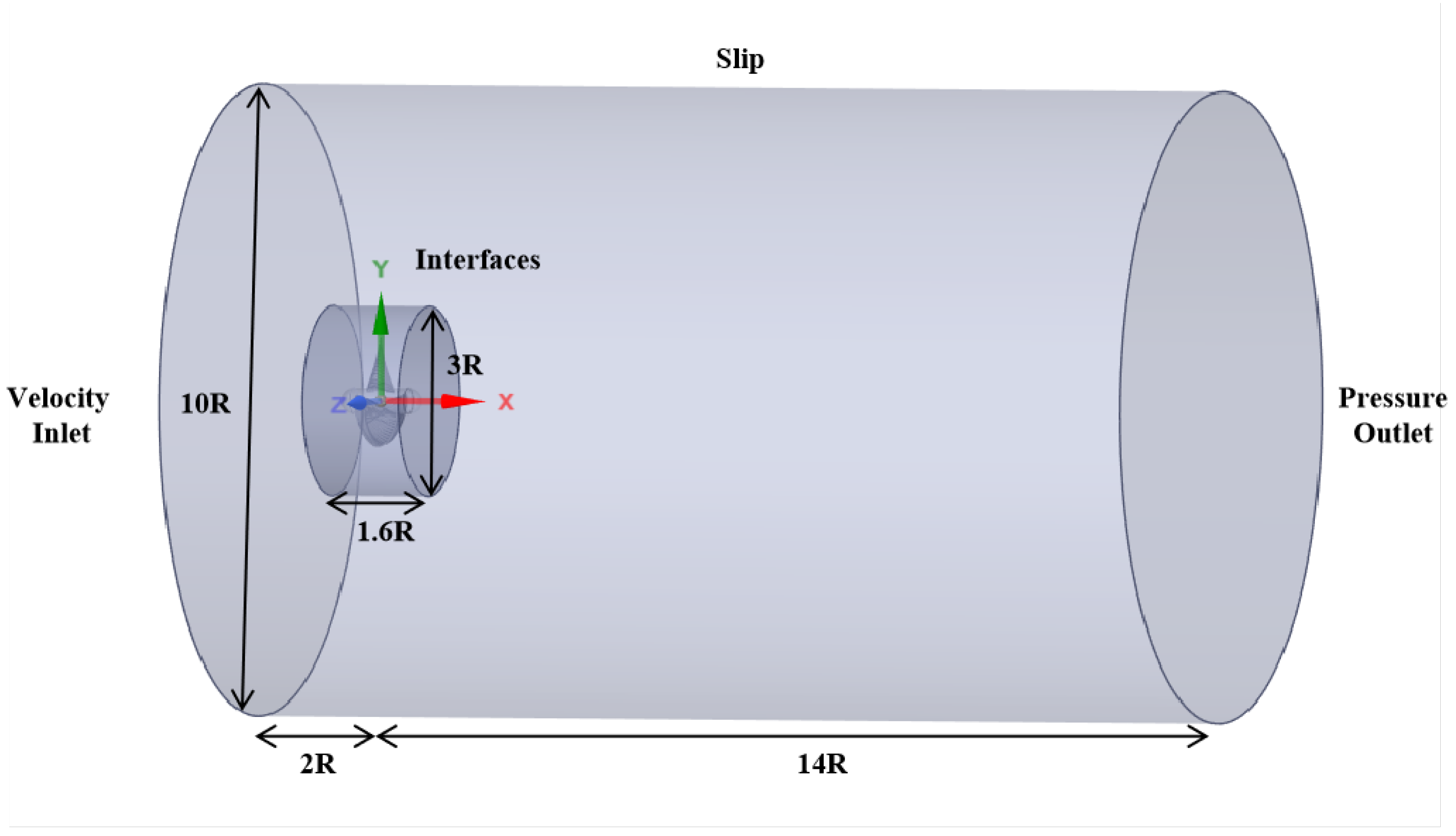

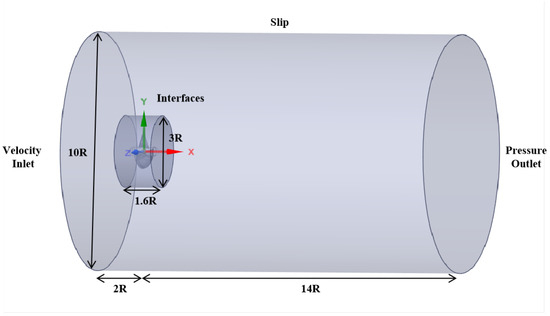

The three-dimensional fluid domains and the boundary conditions are shown in Figure 2. The coordinate system is defined such that the x-axis is aligned with the propeller shaft, while the y- and z-axes lie in the radial plane perpendicular to the shaft axis.

Figure 2.

Schematic of 3D fluid domains and boundary conditions.

The computational domain is divided into a rotating sub-domain containing the propeller and an outer stationary sub-domain. The stationary domain is designed as a cylindrical volume with a diameter of and a length of , while the rotating domain has a diameter of and a length of . The sliding mesh technique is used in the internal interface between the two subdomains. Considering the need to introduce a non-uniform velocity field at the inlet, an excessive distance between the velocity inlet and the propeller disk plane could lead to significant attenuation of the non-uniform velocity distribution during propagation, while placing the inlet too close may cause numerical divergence. Therefore, the inlet is positioned at a distance of .

A velocity inlet boundary condition is applied at the inlet, while a pressure outlet is set at the outlet boundary. The cylindrical surface of the stationary region boundaries is treated as a free-slip wall.

3.3. Two-Scale Wake Inflow Condition

This study applies the two-scale wake model proposed by Zhao et al. [28]. The expressions for , , and are as follows:

where , , L is the characteristic length, the coefficients a, b, c, and d denote the mean axial velocity, the large-scale Fourier mode amplitude, the small-scale Fourier mode amplitude, and the transverse perturbation amplitude, respectively.

To simplify the analysis in the cylindrical computational domain, the velocity components and are transformed into polar coordinates:

where and .

To prevent discontinuities at the domain boundary, a radial decay function is applied to and . An auxiliary component is introduced such that :

Then, in a Cartesian coordinate system, the velocity at the inlet is :

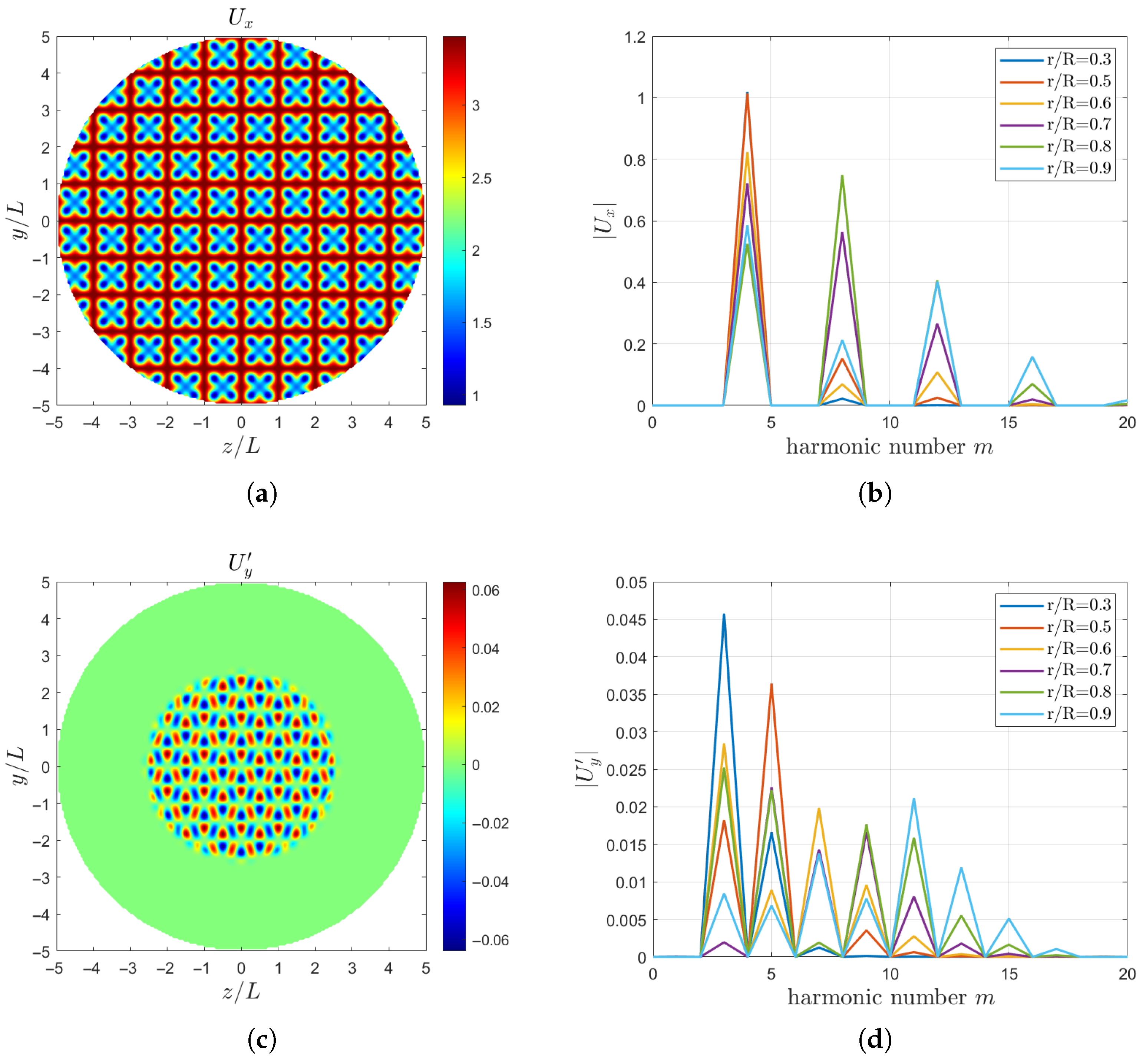

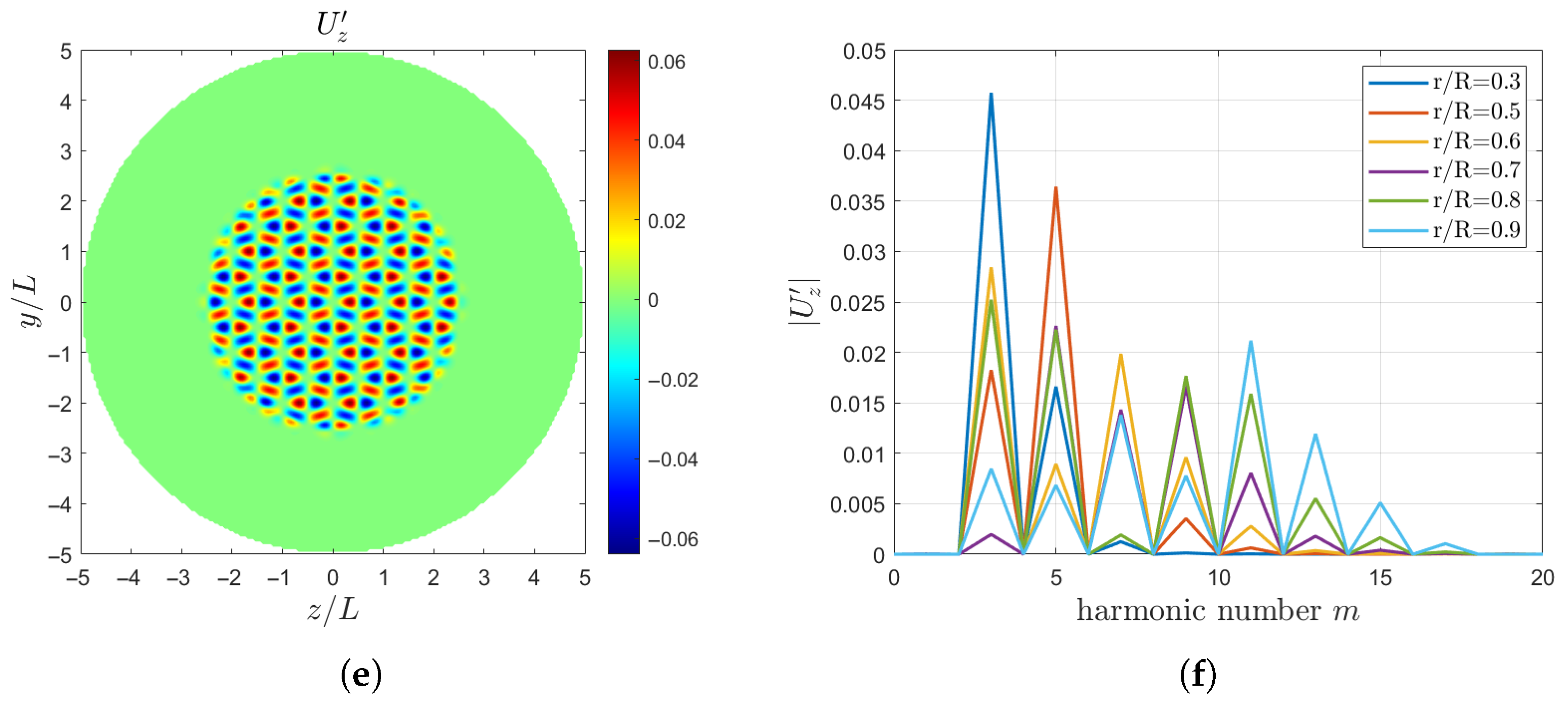

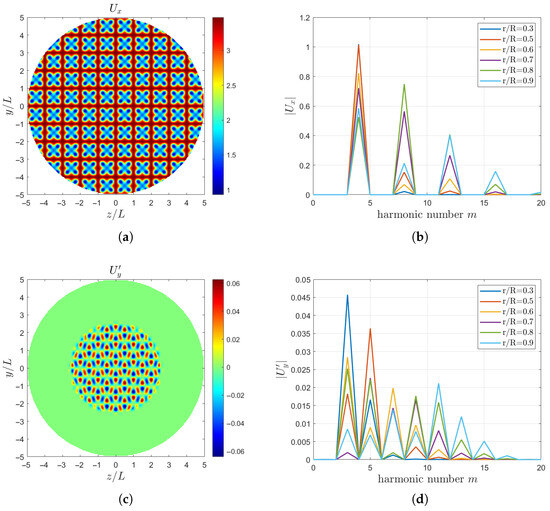

Equations (7), (14), and (15) are directly applied at the inlet boundary to define the velocity field. Figure 3a,c,e show the plots of the axial velocity and the transverse velocities and , while Figure 3b,d,f show their harmonic number spectra at different radial positions (). The harmonic number of are primarily , and those of and are mainly . In the following analysis, the characteristic length L is set equal to the propeller radius R.

Figure 3.

Inlet velocity fields of the two-scale wake model for , , , and : (a) (b) harmonic number of (c) (d) harmonic number of (e) (f) harmonic number of .

4. Verification and Validation

The following dimensionless coefficients [34] are used to express the hydrodynamic performance of a marine propeller:

where J is the advance coefficient, is the advance velocity of the inflow, n is the propeller rotational speed, D is the propeller diameter, is the thrust coefficient, T is the thrust force, is the torque coefficient, Q is the propeller torque, and is the open water efficiency of the propeller.

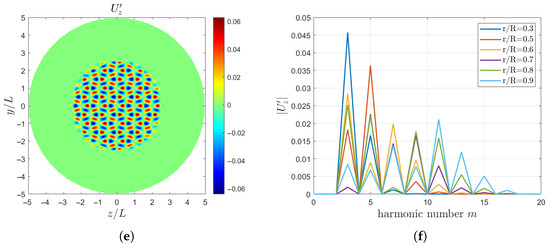

4.1. Mesh Independence Verification

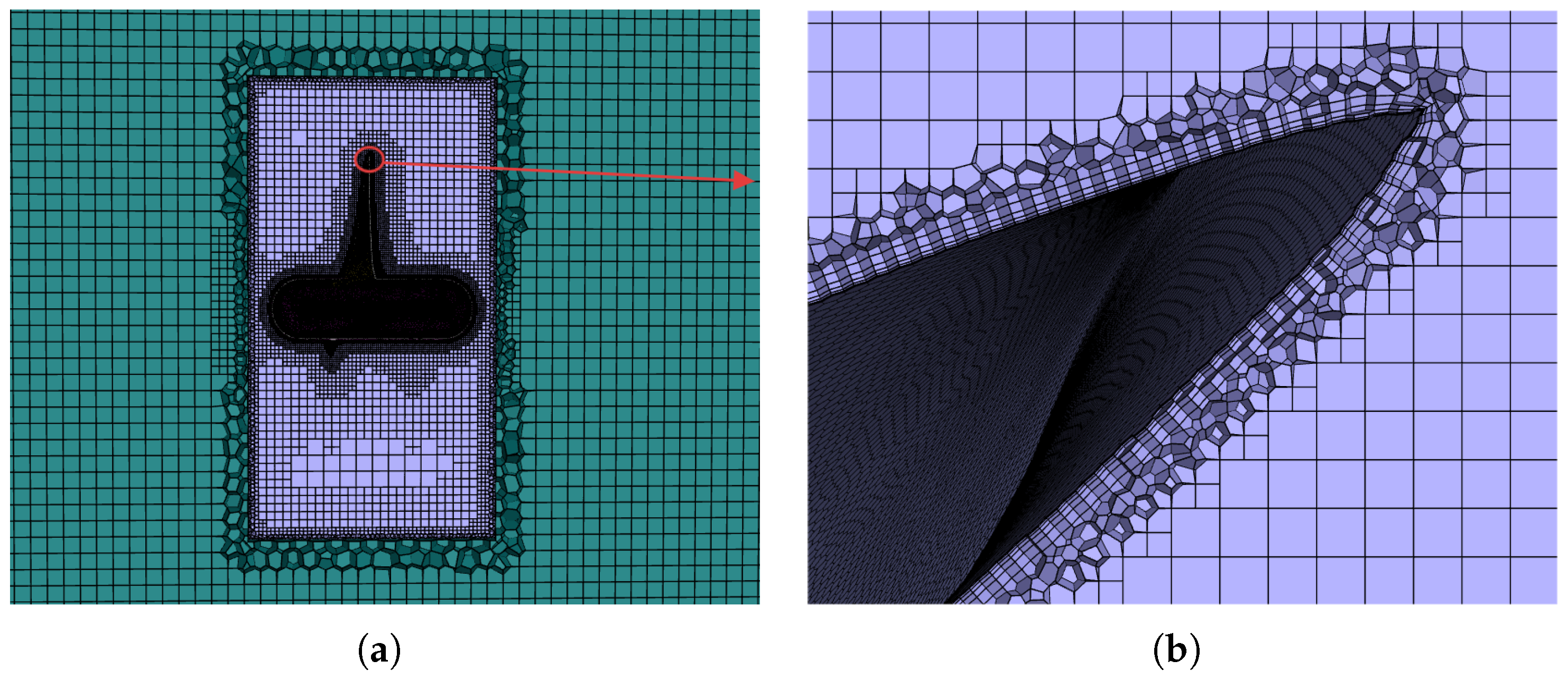

During the meshing process, the mesh is refined at the propeller surface and the interfaces to ensure and to minimize interpolation errors across the AMI zone. The mesh details of the propeller surface and the interface mesh are shown in Figure 4. Five inflation layers are applied near the propeller wall with a growth rate of 1.2.

Figure 4.

Mesh details: (a) AMI interface refinement. (b) Propeller surface refinement.

To assess mesh independence, three sets of computing meshs with different refinement sizes are used under . The simulation results are compared with experimental data [24], as summarized in Table 2. Considering both accuracy and computational efficiency, Mesh 2 is selected for the following computations.

Table 2.

Mesh independence verification.

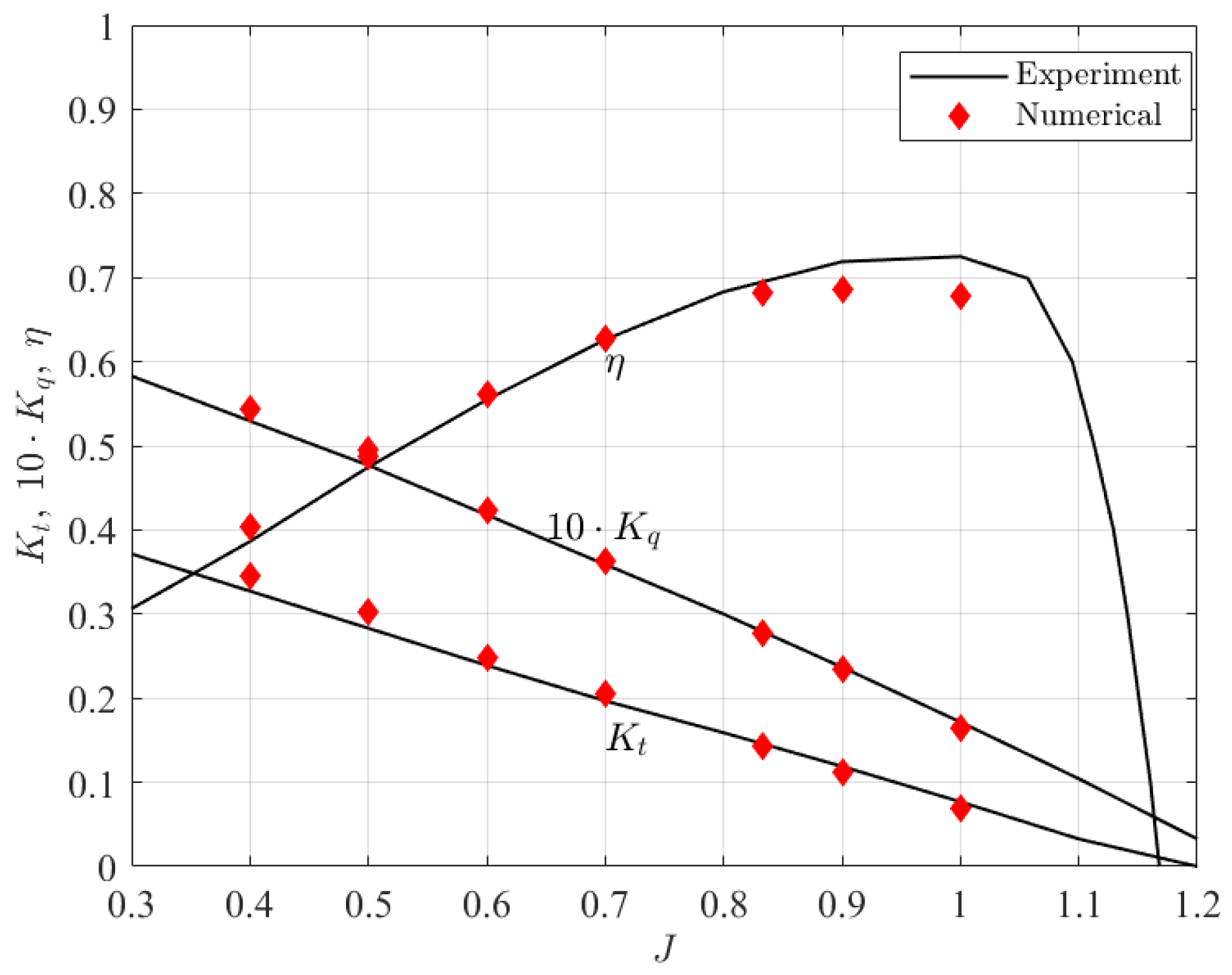

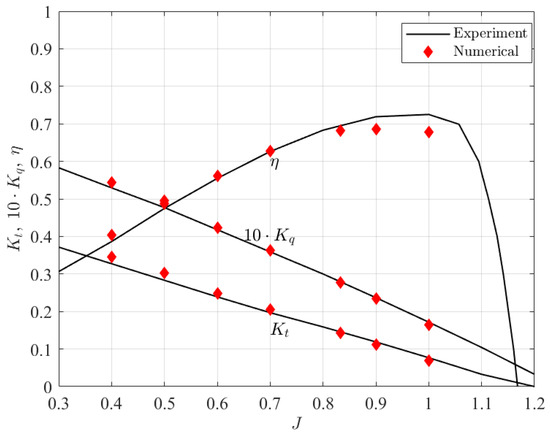

4.2. Propeller Performance in Open Water

Based on the mesh independence study, the validation of the numerical model is conducted by evaluating the open-water performance of the propeller under uniform inflow conditions. The comparison between the numerical results and experimental data [24] is shown in Figure 5. These show that the simulation results of thrust coefficient, torque coefficient, and efficiency are consistent with the experimental data, confirming the reliability of the developed numerical model.

Figure 5.

Comparison of computed and experimental open water performance (non-dimensional).

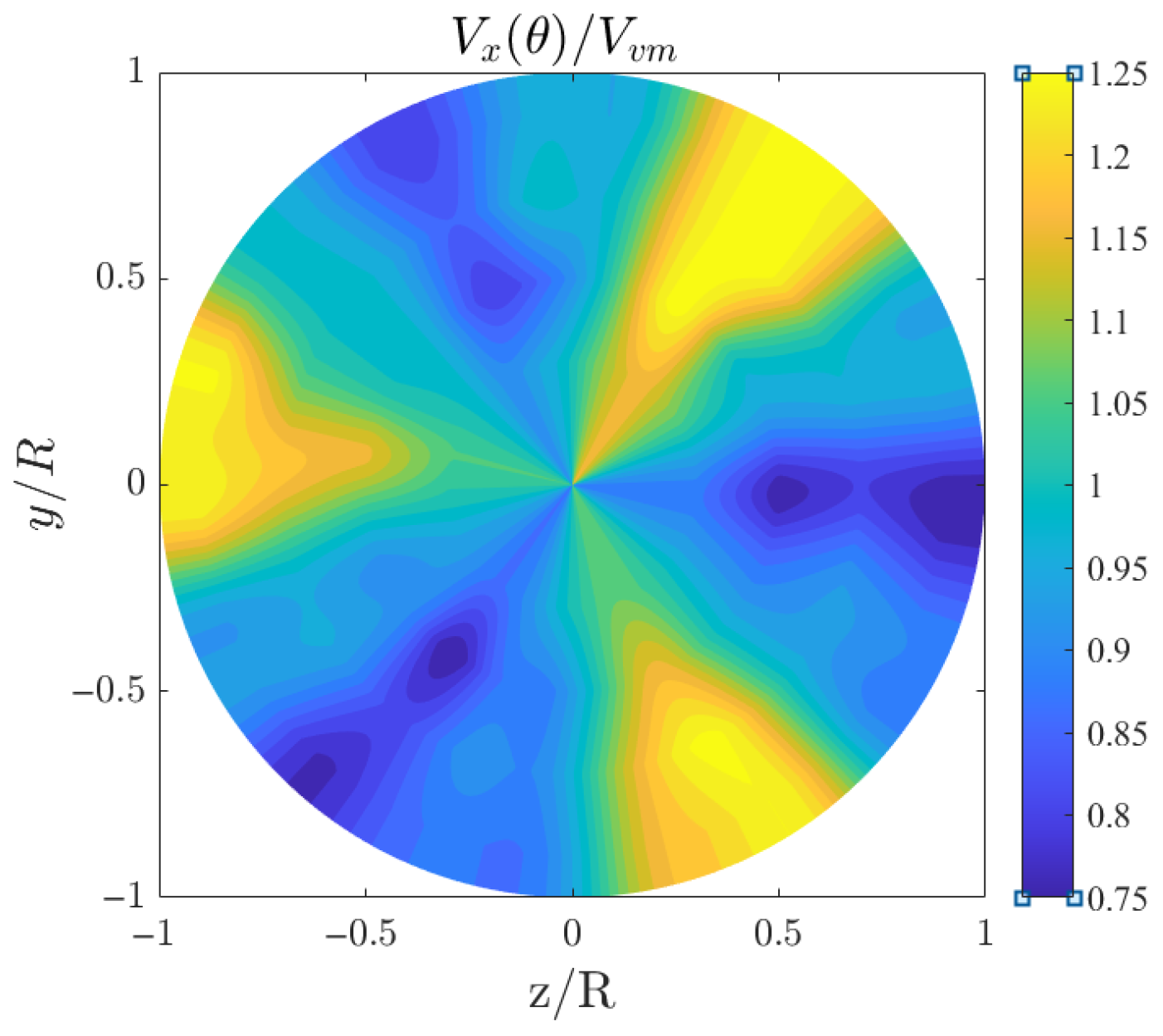

4.3. Propeller Performance in Non-Uniform Inflow

Following validation of the propeller open-water performance, a non-uniform inflow condition was imposed at the inlet to validate the reliability of the model in predicting the unsteady performance of the propeller. The steady non-uniform axial wake field at a given radial position was obtained experimentally, with the wake generated by a three-cycle wake screen [35]. The velocity distribution measured downstream of the screen can be expressed in the form of a Fourier series:

where , is the circumferential averaged axial velocity, is the volume-mean velocity, is the angular coordinate of wake velocity, and and are the coefficients of the Fourier series representing the wake velocity distribution.

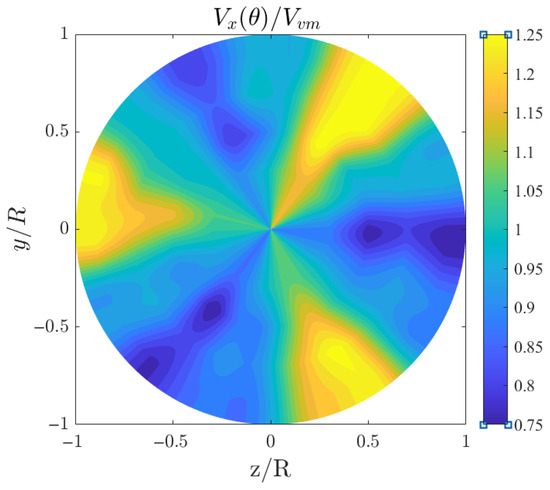

The contour of the inlet velocity obtained by linear interpolation based on the above formula and the values of , A and B is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The velocity field after the three-cycle wake screen.

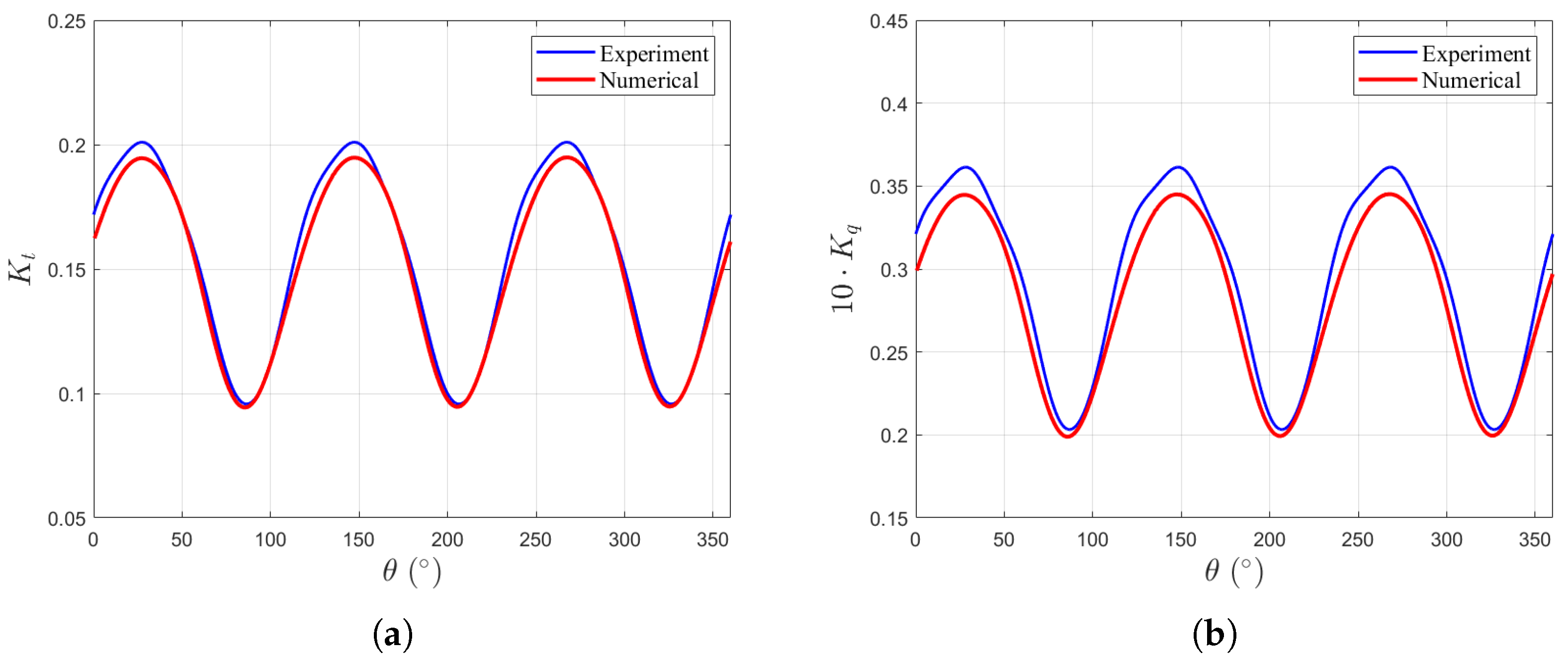

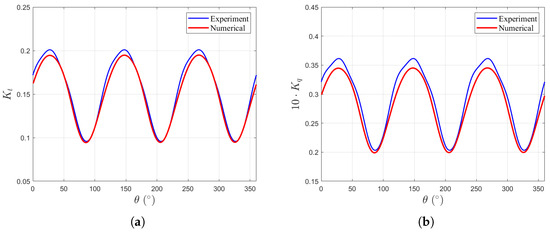

The computed unsteady propeller performance at is compared with experimental data [35]. Figure 7 shows the circumferential variation of the thrust coefficient and the torque coefficient over one propeller revolution. The numerical results show good agreement with the experimental data, capturing both the amplitude and phase of the periodic fluctuations induced by the imposed three-cycle non-uniform inflow.

Figure 7.

Comparison of computed and experimental unsteady propeller performance: (a) unsteady thrust coefficient . (b) Unsteady torque coefficient .

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Inflow Characterization

This subsection quantitatively compares the inflow characteristics of the three-cycle wake and the two-scale wake at the inlet plane. The averaged velocity components and turbulence intensities are defined as

where is the velocity component in the i-direction at the spatial coordinate , A is the total area of the inlet plane, is the root-mean-square of the spatial velocity fluctuations, and is the magnitude of the averaged velocity.

The parameters for the two-scale wake are set as , , , and . The resulting characteristics are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

The comparison of inflow characteristics.

The results show that both inflow conditions maintain nearly identical mean axial velocities, ensuring comparable propeller loading levels. However, the two-scale wake exhibits a much higher axial turbulence intensity () compared to the three-cycle wake (), indicating a stronger degree of non-uniformity in the streamwise velocity field. In addition, the presence of transverse turbulence intensities in the two-scale wake introduces lateral perturbations that are absent in the three-cycle wake.

5.2. Unsteady Force

The lateral forces and only differ by a phase shift, and the moments exhibit similar trends to the corresponding forces . Therefore, the following analysis mainly focuses on thrust and lateral force . The thrust fluctuation amplitude is defined as the normalized mean absolute deviation, expressed as

where is the time-averaged thrust within the selected time interval , and is the time-averaging operator over the same interval.

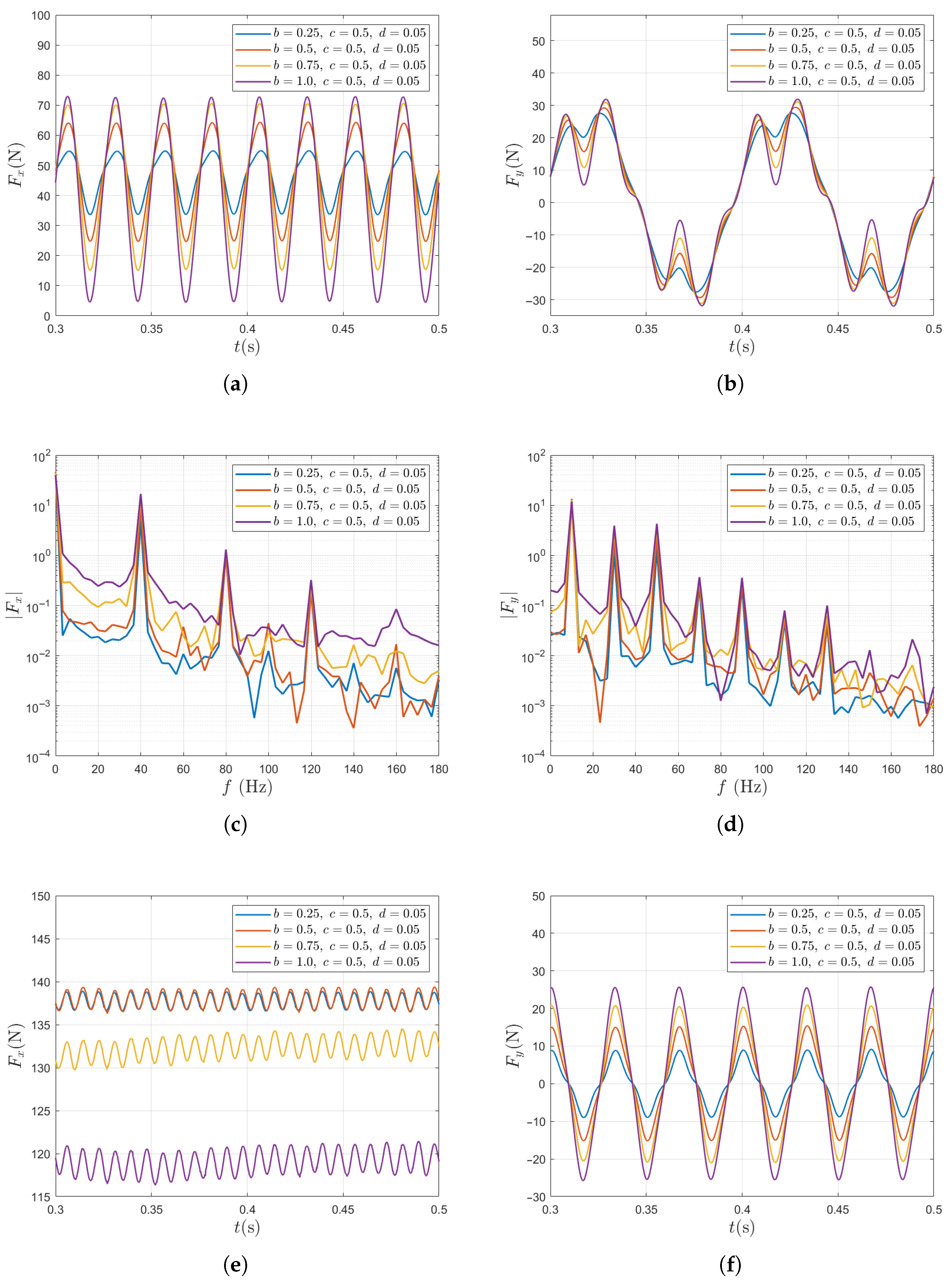

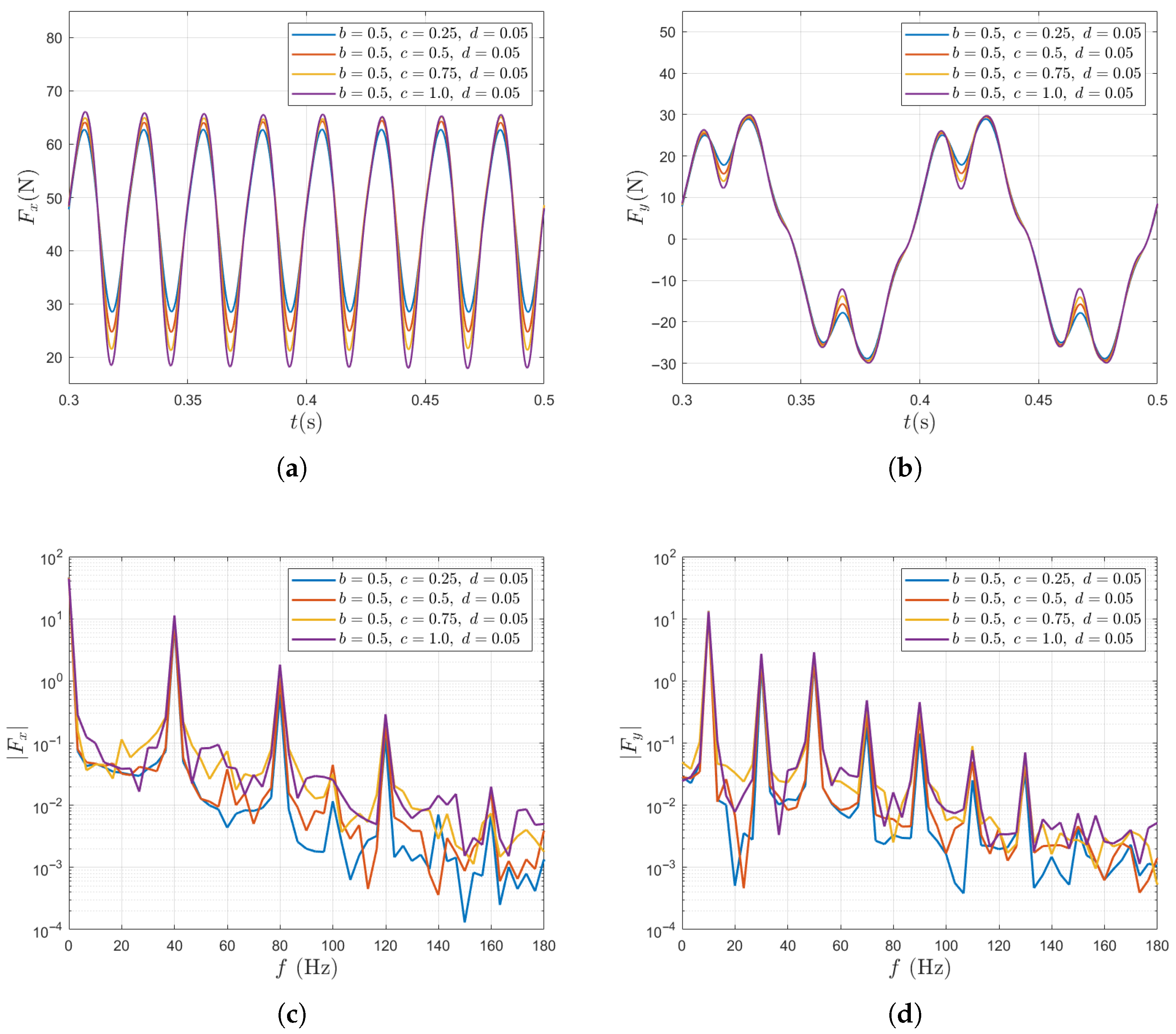

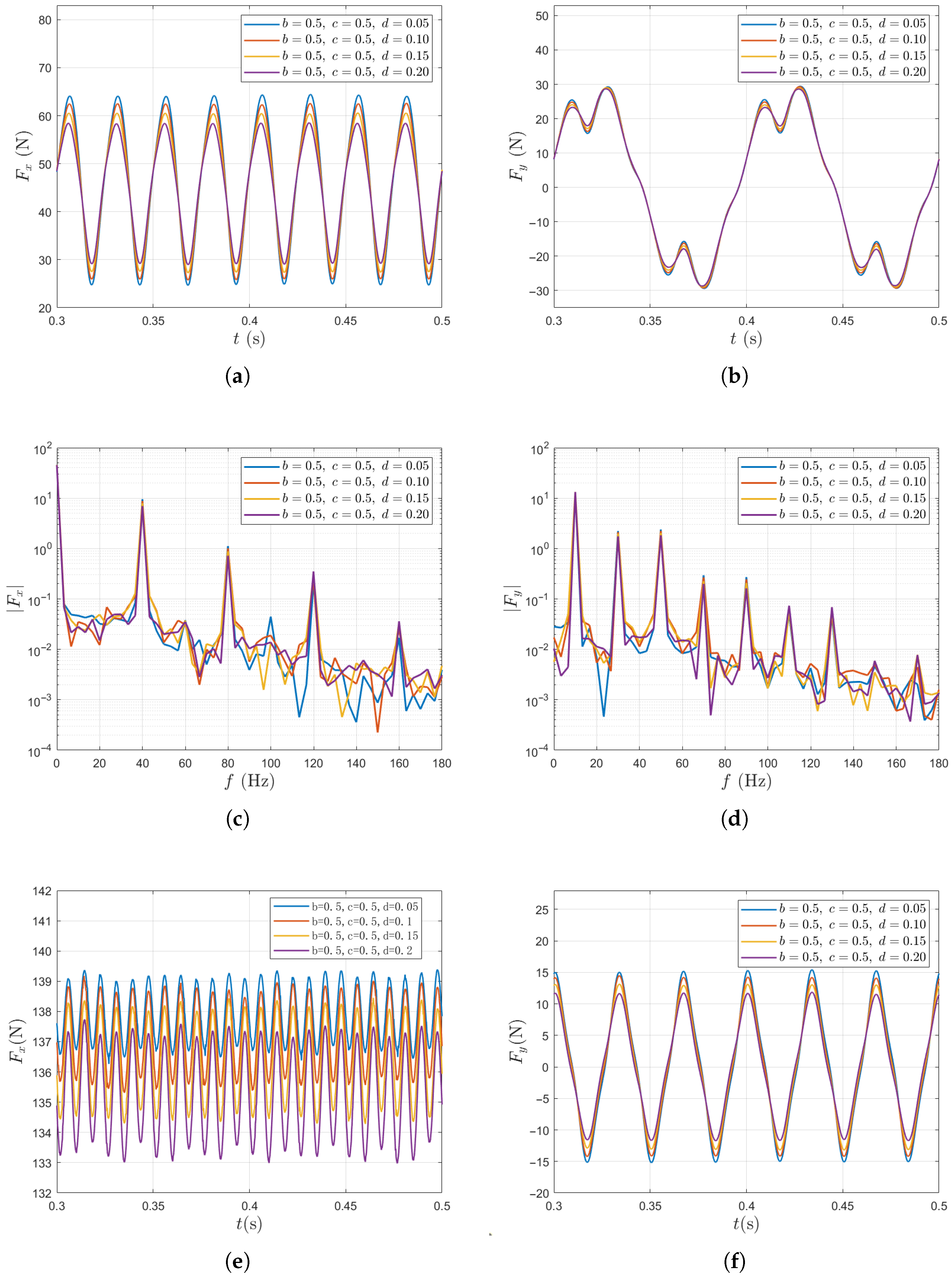

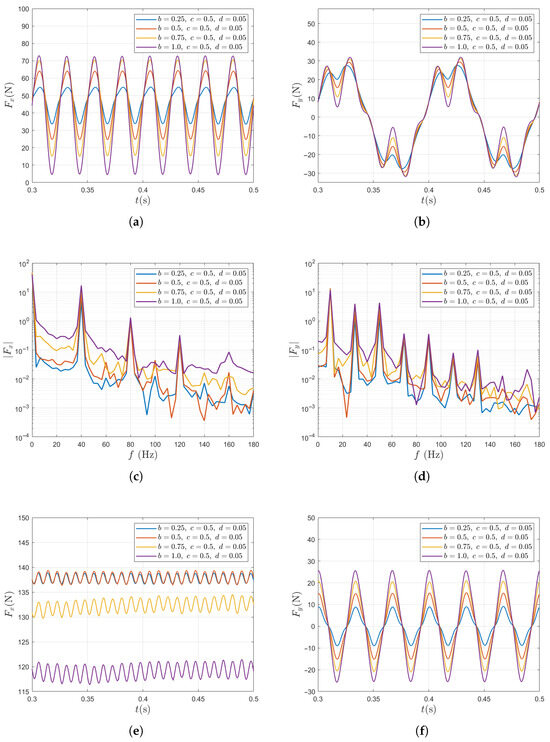

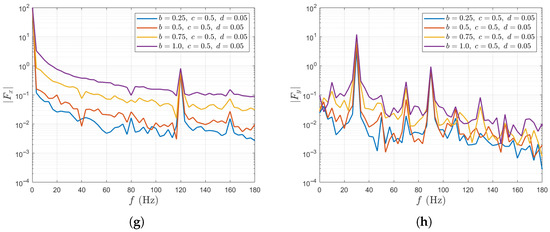

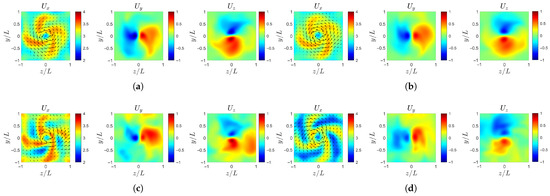

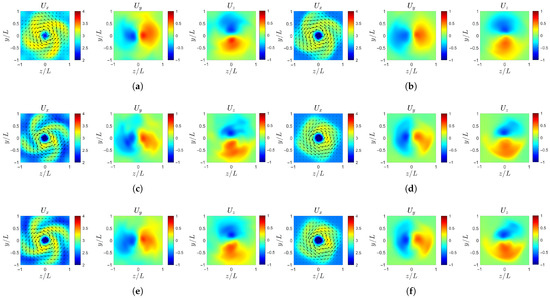

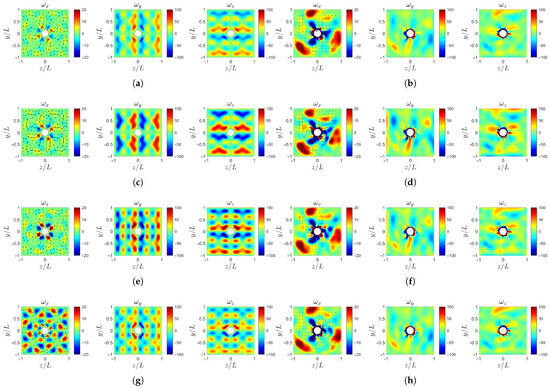

Figure 8 summarizes the results of unsteady force for a single blade and for the entire propeller under variations of the large-scale Fourier mode amplitude b.

Figure 8.

Unsteady force responses for varying b in the two-scale wake inflow. The results of single blade: (a) in time domain, (b) in time domain, (c) in frequency domain, (d) in frequency domain. The results of entire propeller: (e) in time domain, (f) in time domain, (g) in frequency domain, (h) in frequency domain.

For a single blade, as the large-scale Fourier mode amplitude b increases from 0.25 to 1, the fluctuation amplitude of the thrust increases significantly from 13.8% to 53.71%, indicating a strong sensitivity to large-scale inflow disturbances (Figure 8a). Meanwhile, the fluctuation of the lateral force also increases, although to a much lesser extent (Figure 8b). The frequency spectrum of is dominated by peaks corresponding to the axial inflow harmonic number (). Given the propeller’s fundamental frequency , these peaks appear at , and (Figure 8c), indicating that the unsteady thrust is primarily governed by the harmonic number of the axial inflow . The frequency spectrum of is mainly influenced by the propeller’s fundamental frequency and the harmonic number () of transverse velocity . Its major peaks appear at , and (Figure 8d).

For the entire propeller, as the large-scale Fourier mode amplitude b increases from 0.25 to 1, the time-averaged total thrust decreases by 13.6% (Figure 8e). Since the harmonic number of satisfies (K is a positive integer), large-amplitude unsteady lateral forces are generated. Due to the phase superposition and cancellation among the three blades, the total thrust of the propeller shows peaks only at , whereas the total lateral forces and exhibit peaks only at and .

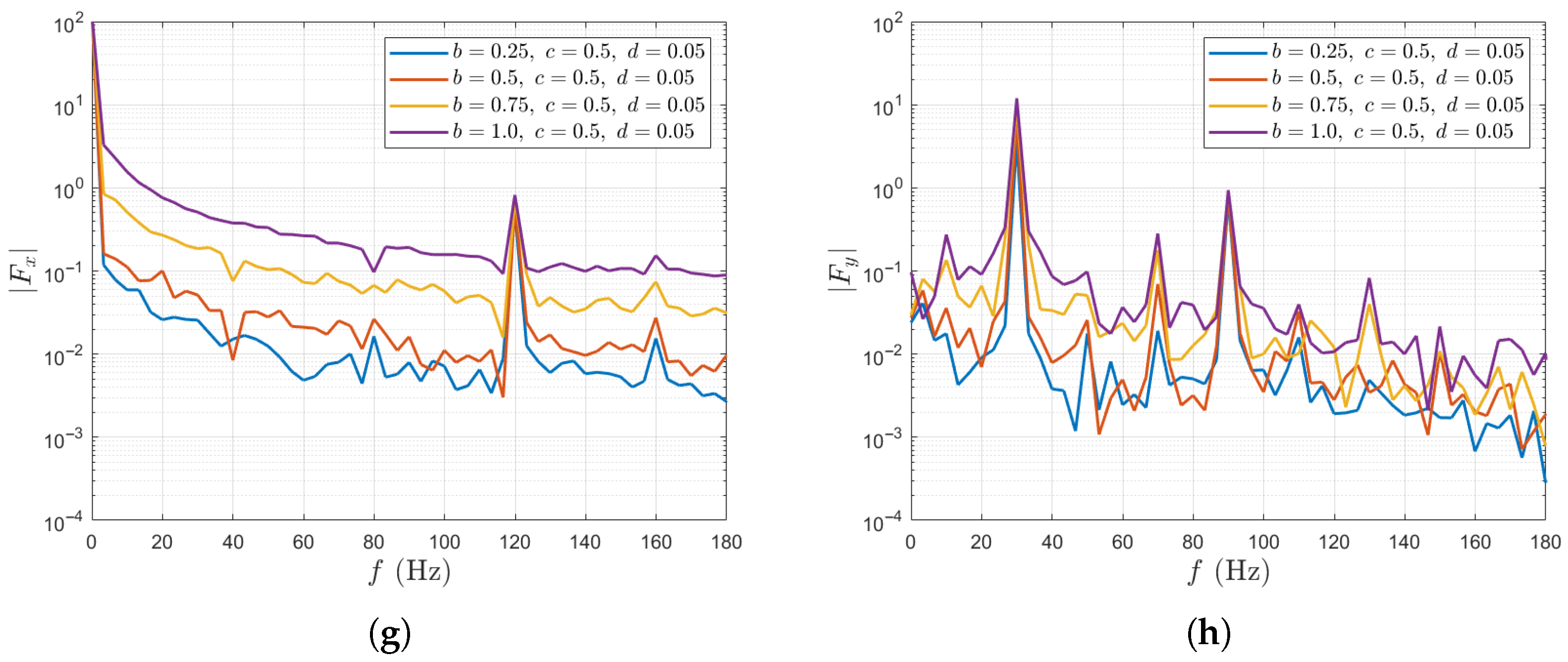

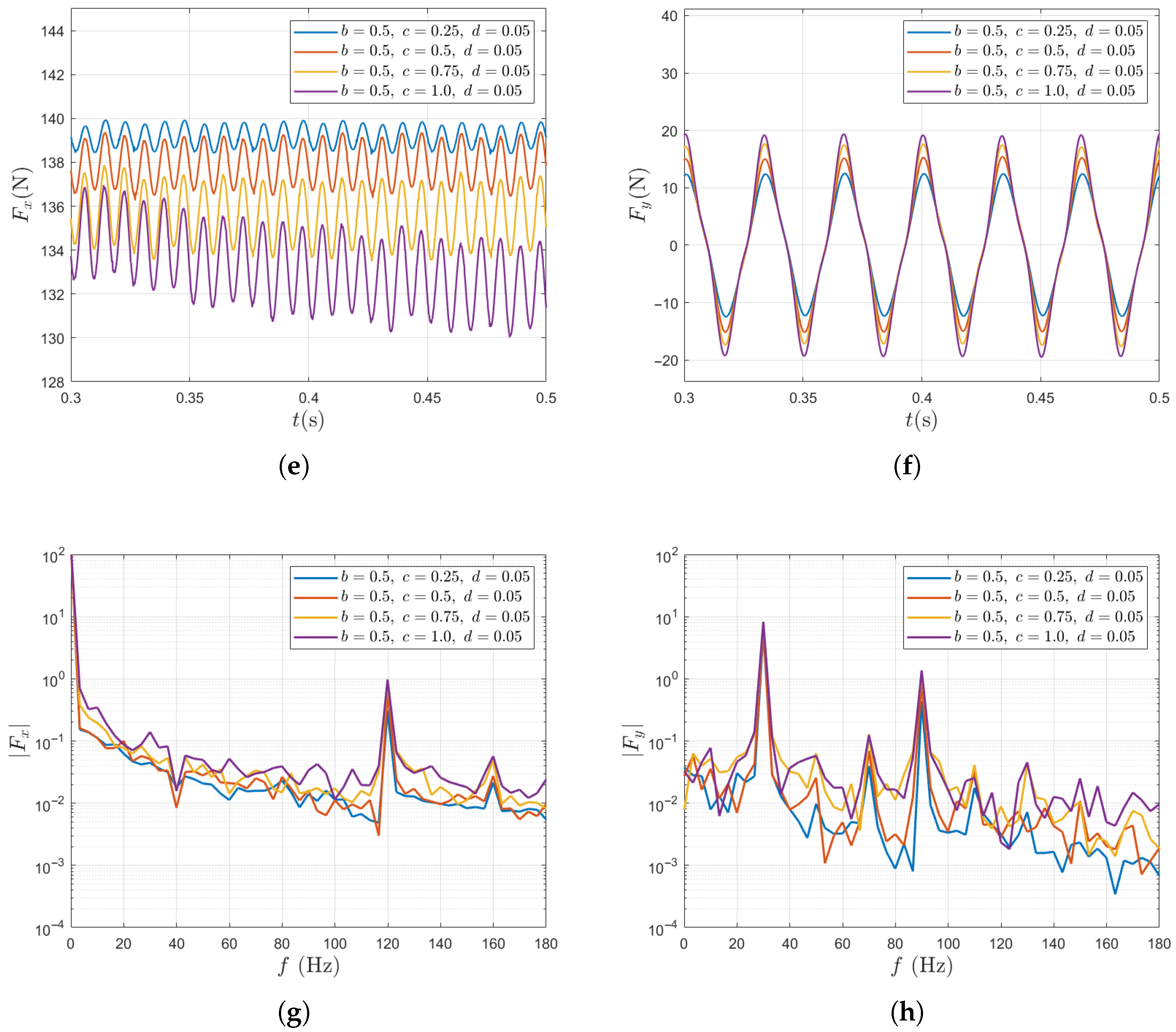

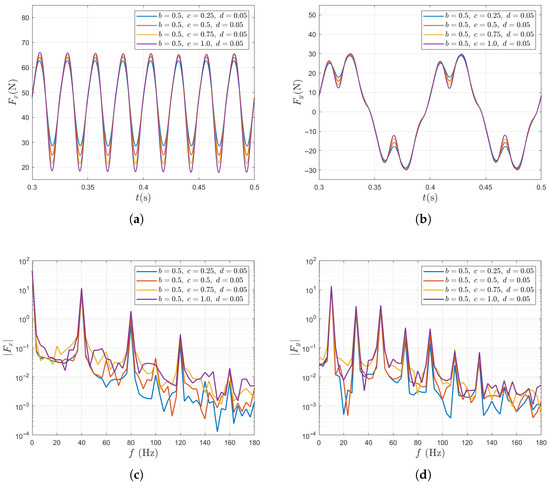

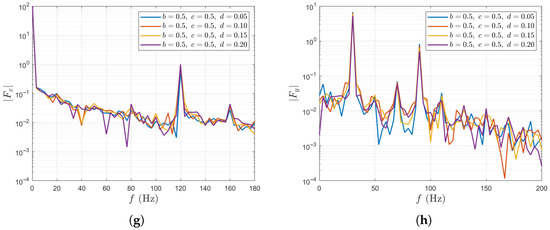

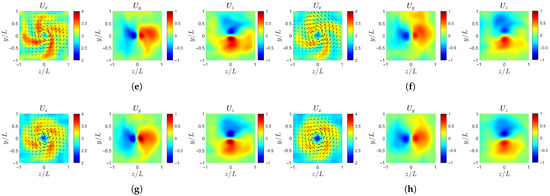

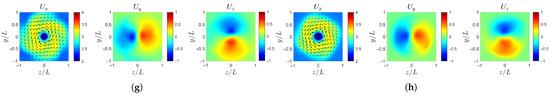

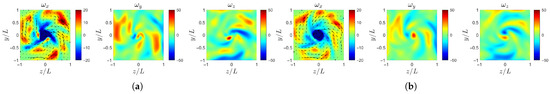

Figure 9 summarizes the unsteady force results for a single blade and for the entire propeller under variations of the small-scale Fourier mode amplitude c. For a single blade, increasing c slightly increases the fluctuation amplitudes of both the thrust force and the lateral force . Specifically, as c increases from 0.25 to 1.0, the fluctuation amplitude of the thrust force increases from 22.95% to 32.48%. This suggests that a small-scale contributes to enhanced unsteadiness. However, the overall fluctuation level remains predominantly governed by the large-scale component, as indicated by the fixed value (which already yields a fluctuation of 26.27%). In the frequency domain, while the force spectra exhibit peaks at the same harmonic frequencies as in the previous case, increasing c primarily amplifies the response at higher-order harmonics. For the entire propeller, the time-averaged total thrust shows a similar decreasing trend, with a 4.2% reduction as c increases from 0.25 to 1.0. Overall, for both the single blade and the entire propeller, the unsteady force fluctuations are less sensitive to variations in c than to those in b.

Figure 9.

Unsteady force responses for varying c in the two-scale wake inflow. The results of single blade: (a) in time domain, (b) in time domain, (c) in frequency domain, (d) in frequency domain. The results of entire propeller: (e) in time domain, (f) in time domain, (g) in frequency domain, (h) in frequency domain.

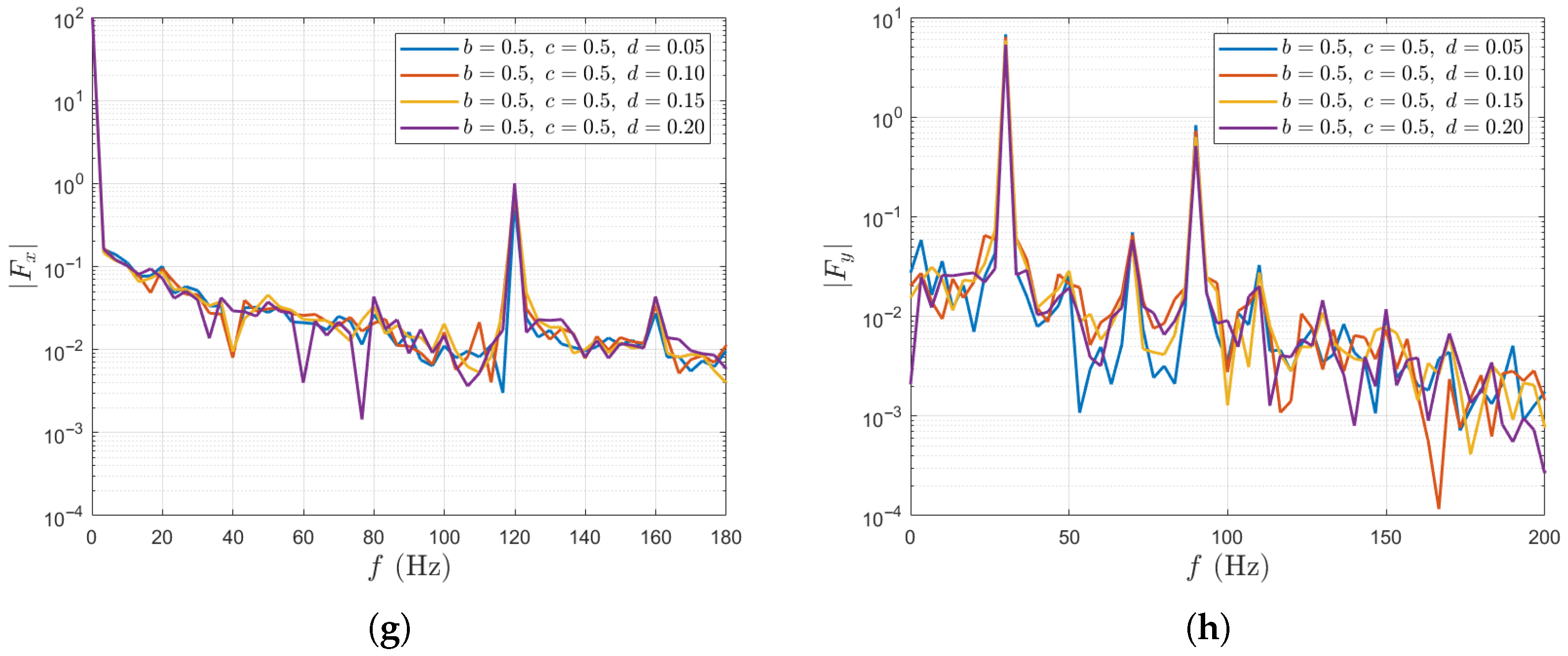

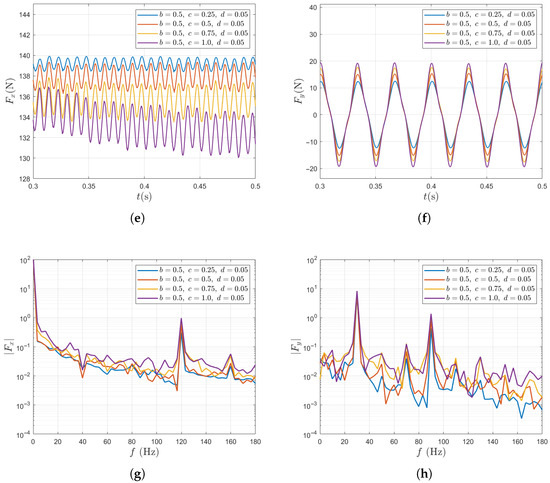

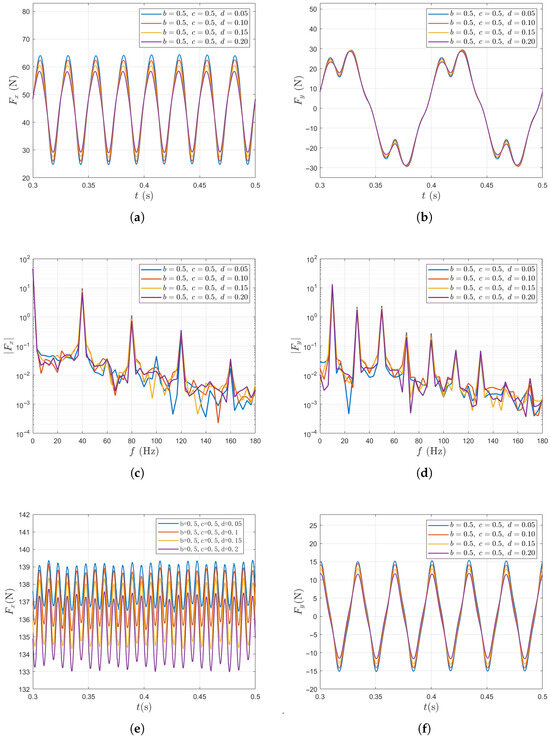

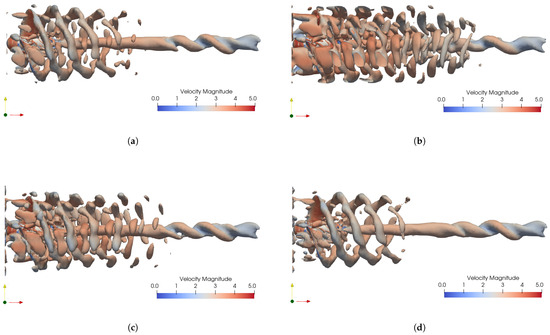

Figure 10 summarizes the results of unsteady force for a single blade and for the entire propeller under variations of the transverse perturbation amplitude d. For a single blade, the fluctuation amplitudes of thrust and lateral force decrease as d increases, which may be attributed to the increase in transverse velocities that weakens the non-uniformity of the axial inflow. Specifically, as d increases from 0.05 to 0.2, the thrust fluctuation amplitude of a single blade decreases from 26.3% to 19.4%. For the entire propeller, the fluctuation amplitude of the total thrust shows a slight increase of only 1.89% as d increases, while the total lateral force follows the trend observed in the single blade case, with its fluctuation amplitude decreasing by approximately 20%.

Figure 10.

Unsteady force responses for varying d in the two-scale wake inflow. The results of single blade: (a) in time domain, (b) in time domain, (c) in frequency domain, (d) in frequency domain. The results of entire propeller: (e) in time domain, (f) in time domain, (g) in frequency domain, (h) in frequency domain.

From the above results, it is evident that the three parameters have different influences on the unsteady force responses (Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10). The large-scale Fourier mode amplitude b exerts the strongest effect, significantly amplifying the single blade thrust fluctuations and reducing the mean thrust of the entire propeller. In contrast, variations in the small-scale amplitude c mainly affect the higher-order harmonics, increasing their amplitudes while having a weaker impact on the overall force magnitudes. The transverse perturbation reduces the single blade force fluctuations by weakening the axial non-uniformity, yet slightly increases the whole-propeller fluctuations due to phase differences among blades. However, it shows potential in reducing the lateral force fluctuation of the entire propeller.

5.3. Pressure Fluctuation on the Propeller Surface

To provide an intuitive comparison of how the large-scale Fourier mode amplitude (b), small-scale Fourier mode amplitude (c), and transverse perturbation amplitude (d) influence the wake vortex structures of propeller, four representative cases are selected, as listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Parameter settings of each case.

The unsteady forces generated on the propeller blades primarily originate from the pressure fluctuations on the blade surfaces. The intensity of pressure fluctuations at each node on the blade surface is quantified using the root-mean-square value of pressure fluctuation, defined as

where is instantaneous pressure at time step , is the time-average pressure, and is the total number of time steps.

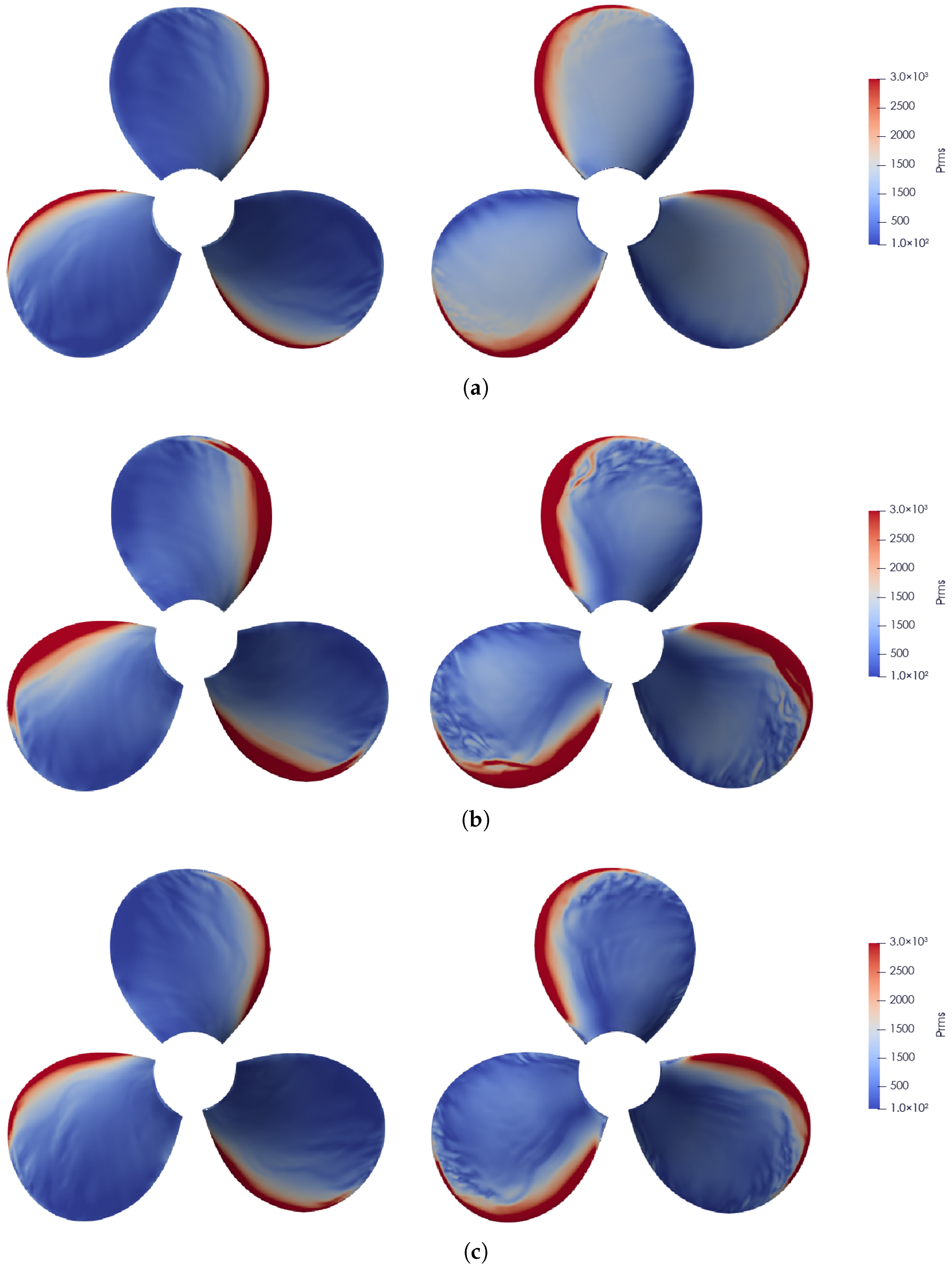

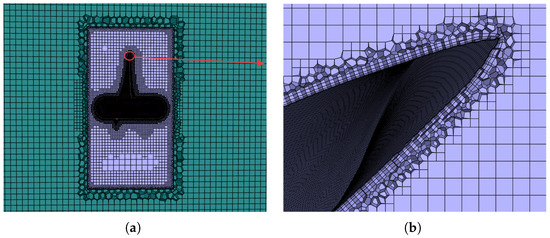

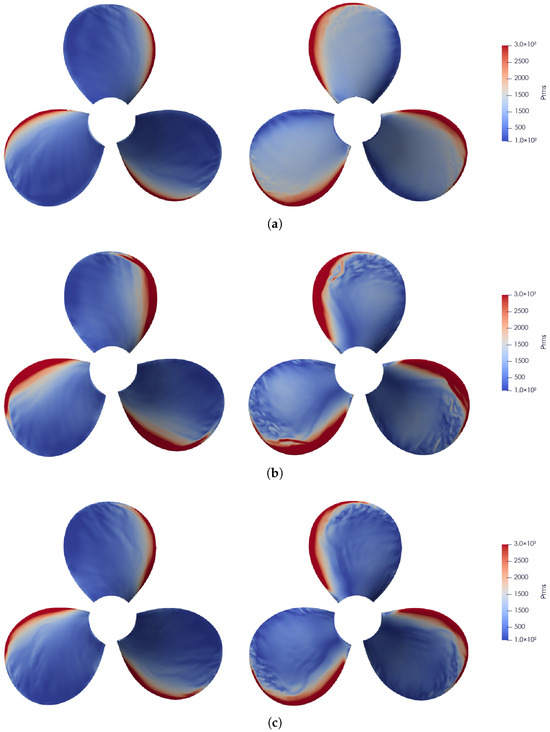

The Figure 11 shows the spatial distribution of pressure fluctuation on both the pressure side (left half) and the suction side (right half) of the propeller blade for the four representative inflow conditions. Due to the inflow non-uniformity, the local angle of attack experienced by the blade varies during rotation, resulting in a prominent high-pressure-fluctuation strip along the leading edge.

Figure 11.

Pressure fluctuation on the propeller surface. For each subfigure, the left half shows the pressure side and the right half shows the suction side: (a) case-ori, (b) case-b, (c) case-c, (d) case-d.

For case-ori on the suction side, a distinct low-fluctuation region appears near the trailing edge, while the mid-chord area exhibits a relatively uniform distribution of pressure fluctuation. As the amplitudes of the large-scale Fourier mode b and the small-scale Fourier mode c increase, the extent of the high fluctuation region along the leading edge on both sides becomes noticeably enlarged, whereas increasing the transverse perturbation amplitude d suppresses it. This trend is consistent with the single blade unsteady thrust behavior discussed in the previous section.

In addition, increasing b, c, or d leads to a more pronounced non-uniformity in the pressure fluctuations near the blade tip on the suction side, which may be attributed to the intensified interaction between the incoming perturbations and tip vortex. Furthermore, a larger d markedly reduces the overall pressure fluctuation level across the entire blade surface.

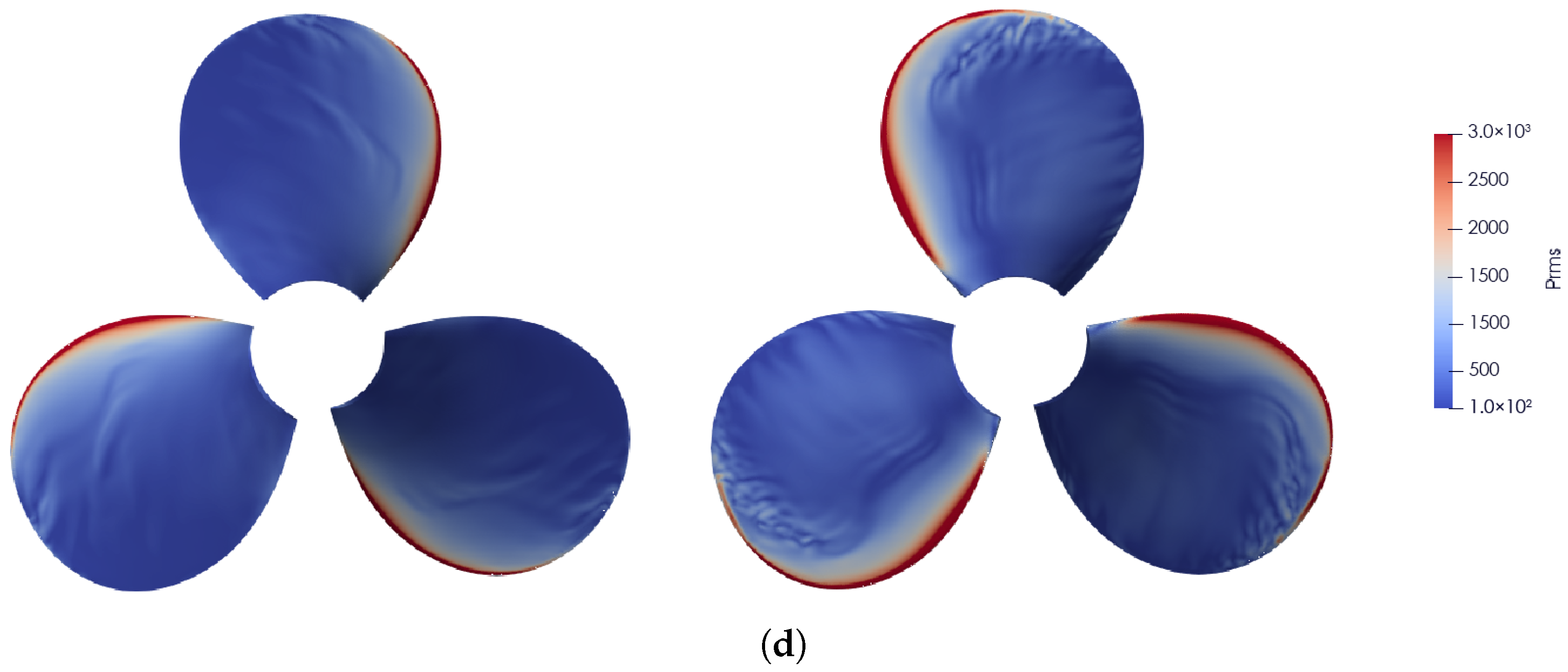

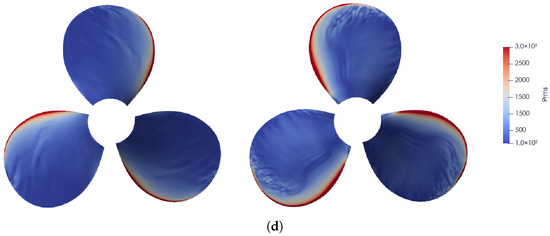

5.4. Vortex Structures

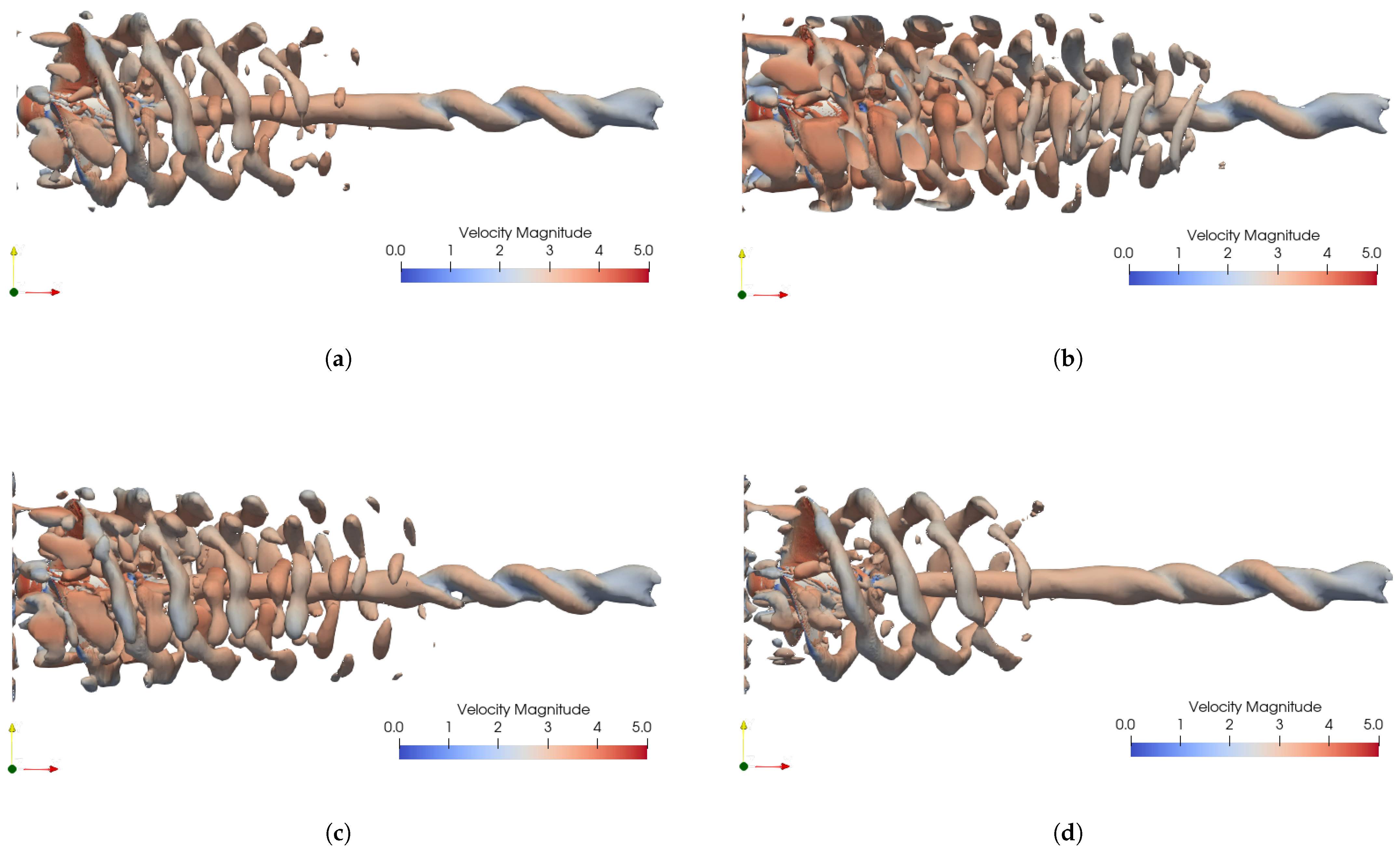

Figure 12 shows the three-dimensional vortex structures of the propeller wake in the four cases at . The vortices are visualized using the Q-criterion () and colored by the local velocity magnitude. In the baseline case-ori, the wake exhibits a relatively regular helical structure, where the tip vortices [36] remain coherent and undergo only limited deformation as they convect downstream. In the hub-side region, the inflow vortex structures that are not dissipated by the rotating blades are entrained and wrapped by the tip vortices, gradually breaking down during downstream convection. The breakdown of these small-scale vortices locally disturbs the helical organization of the tip-vortex system.

Figure 12.

Three-dimensional vortex structures of the propeller wake (, ): (a) case-ori, (b) case-b, (c) case-c, (d) case-d.

When the large-scale Fourier mode amplitude b increases (case-b), the wake structure becomes highly distorted, and the helical tip-vortex pattern can no longer be clearly identified. The intensified large-scale allows more residual vortex structures to pass through the rotating blades, enhancing vortex–vortex interactions and producing vortex fragmentation. As a result, the wake becomes more chaotic and spatially expanded downstream.

In contrast, when the small-scale Fourier mode amplitude c increases (case-c), more inflow vortex structures are transmitted through the rotating blades, leading to an earlier breakdown of the helical tip-vortex system and a broader downstream spreading of the wake. Nevertheless, the overall helical configuration remains discernible, and the influence of c is less pronounced compared with that of the large-scale Fourier mode b.

When the transverse perturbation amplitude d is introduced (case-d), the wake shows reduced vortex distortion compared with case-ori. This indicates that lateral perturbations mitigate the transmission of residual vortex disturbances through the rotating blades, leading to smoother vortex filaments and a more coherent helical wake structure downstream.

The subsequent analysis investigates the evolution of velocity and vorticity distributions downstream of the propeller to clarify the flow features associated with different inflow parameters.

5.5. Velocity Field

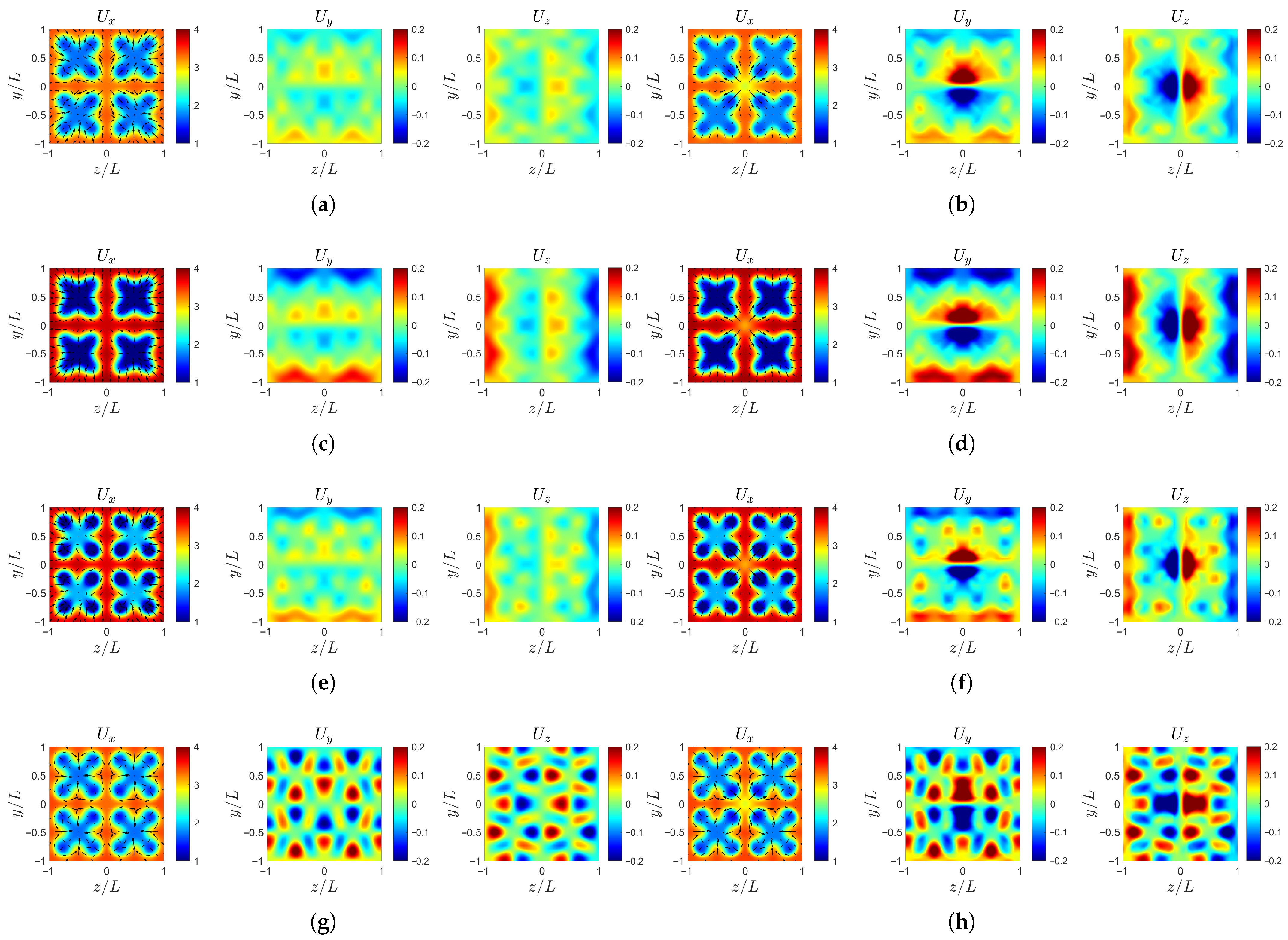

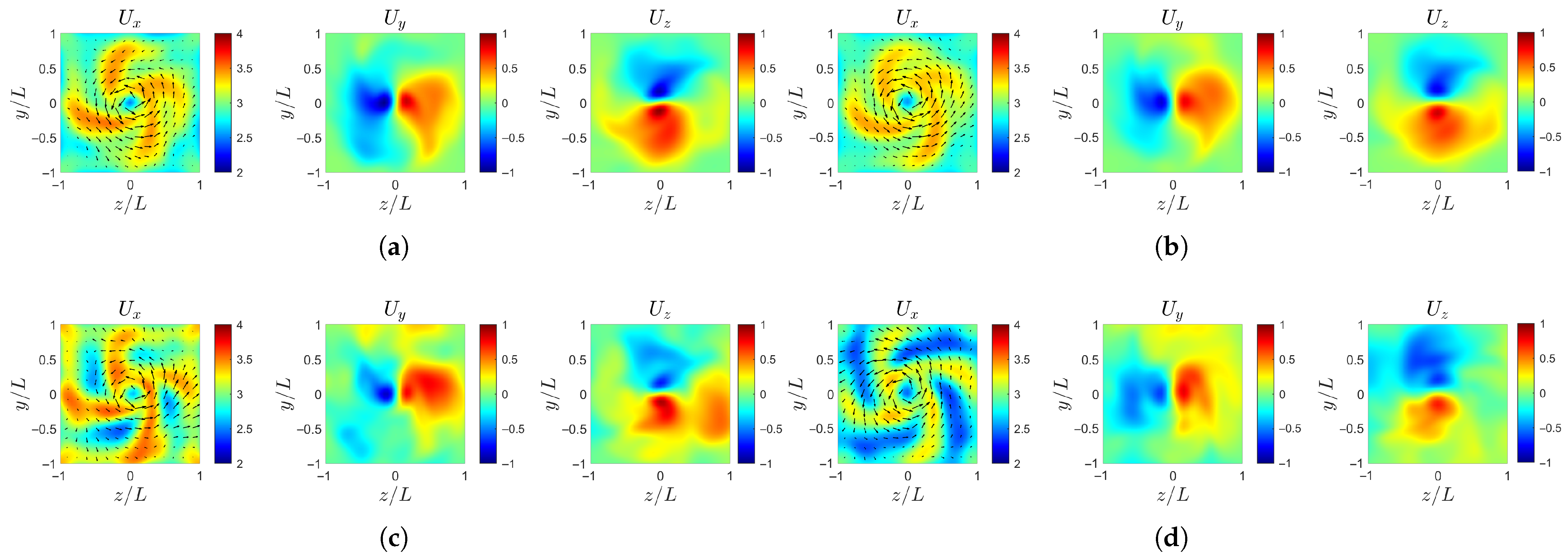

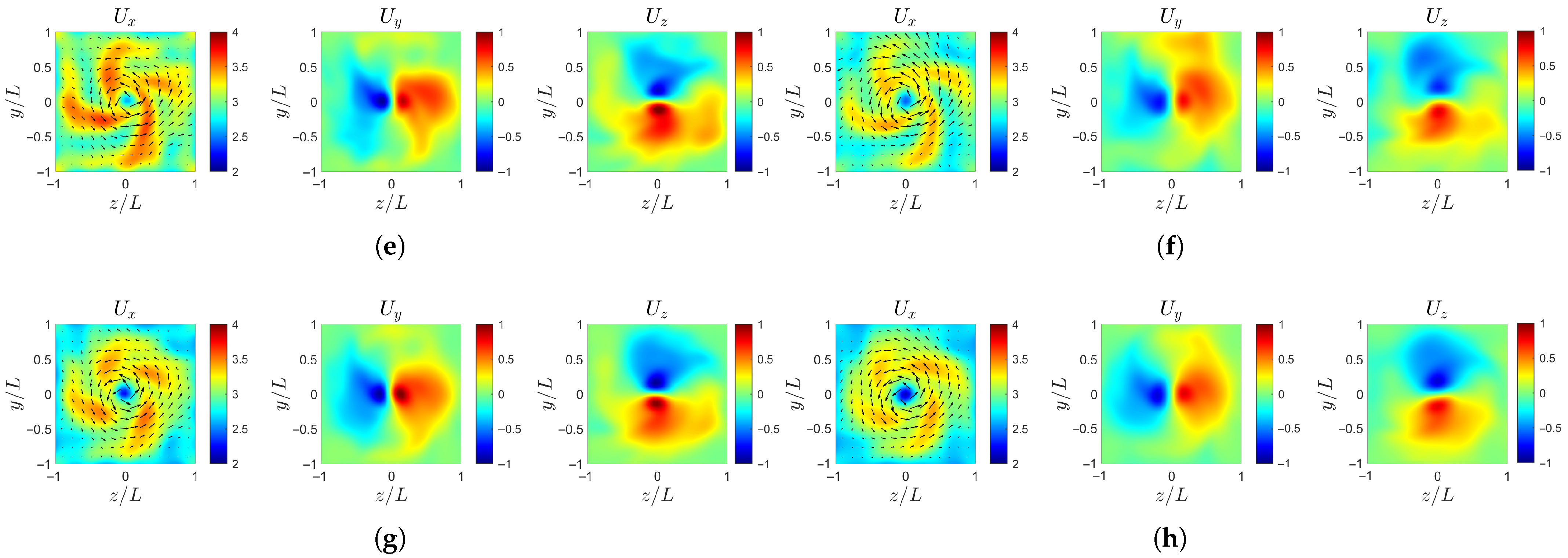

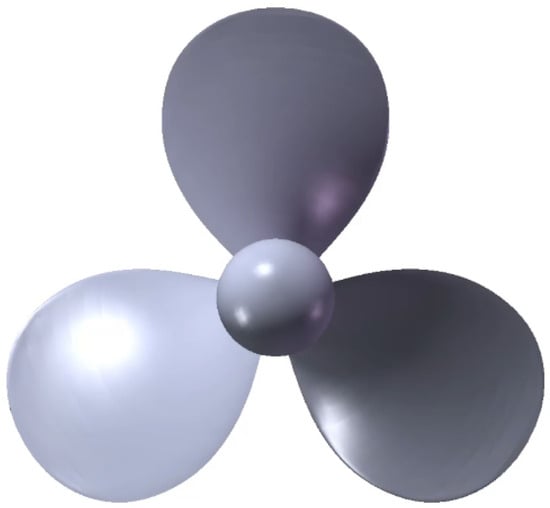

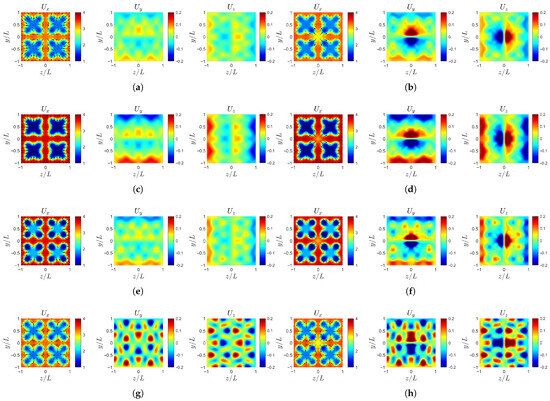

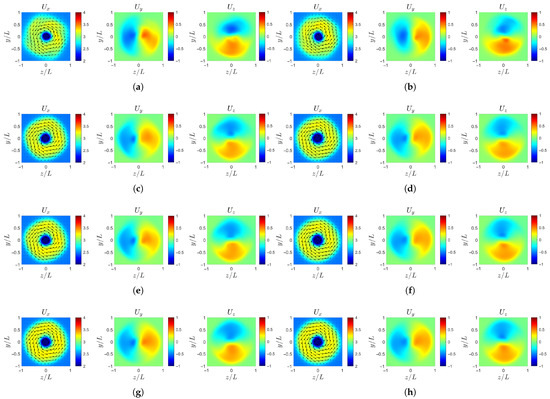

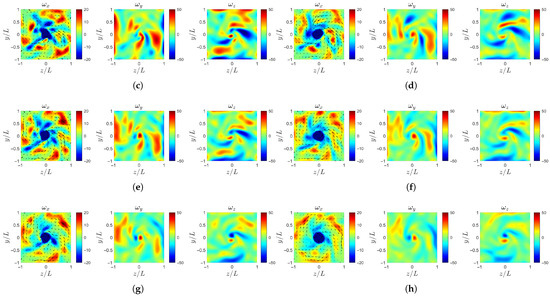

The velocity field analysis compares the four cases described above to investigate the downstream evolution of the wake induced by different perturbation amplitudes. The analysis mainly focuses on the region and . The velocity profiles are extracted from the instantaneous flow field at . The velocity profile of is superimposed with the directions of transverse components and , which are indicated by arrows.

As shown in Figure 13, at the upstream plane , the axial velocity of all cases still retains the inlet distribution characteristics, while the transverse velocity gradually converges toward the center as the flow approaches the rotating sub-domain. The large-scale Fourier mode amplitude b exhibits a stronger influence on the transverse disturbance structure compared with the small-scale Fourier mode amplitude c. However, when the transverse perturbation amplitude d is sufficiently large (comparable to 50% of b and c), the transverse velocity preserves its periodic characteristics before entering the rotating sub-domain. At the interface of , the effect of the propeller’s rotation further enhances the centralization of the transverse velocity field. The arrows in the field consistently point from high-velocity regions towards low-velocity regions, which is particularly evident in case-d (Figure 13h). This indicates that the transverse disturbances actively contribute to homogenizing the axial flow field.

Figure 13.

Instantaneous velocity profile at : (a) case-ori at . (b) case-ori at . (c) case-b at . (d) case-b at . (e) case-c at . (f) case-c at . (g) case-d at . (h) case-d at .

After entering the rotating region, from to , the velocity field undergoes significant changes as the flow passes through the propeller blades. As shown in Figure 14, the small-scale in the axial velocity is dissipated, while the central high-speed region of the large-scale develops into spiral arm-like patterns [37]. However, case-b (Figure 14d) has the strongest large-scale amplitude, and its dominant features are preserved even after being cut and redistributed by the propeller blades. The increase in large-scale Fourier mode amplitude and the small-scale Fourier mode amplitude exacerbates the entrainment and suction effect of the hub vortex recirculation zone. The influence of the small-scale is notably more significant, as shown by the arrows in Figure 14f.

Figure 14.

Instantaneous velocity profile at : (a) case-ori at . (b) case-ori at . (c) case-b at . (d) case-b at . (e) case-c at . (f) case-c at . (g) case-d at . (h) case-d at .

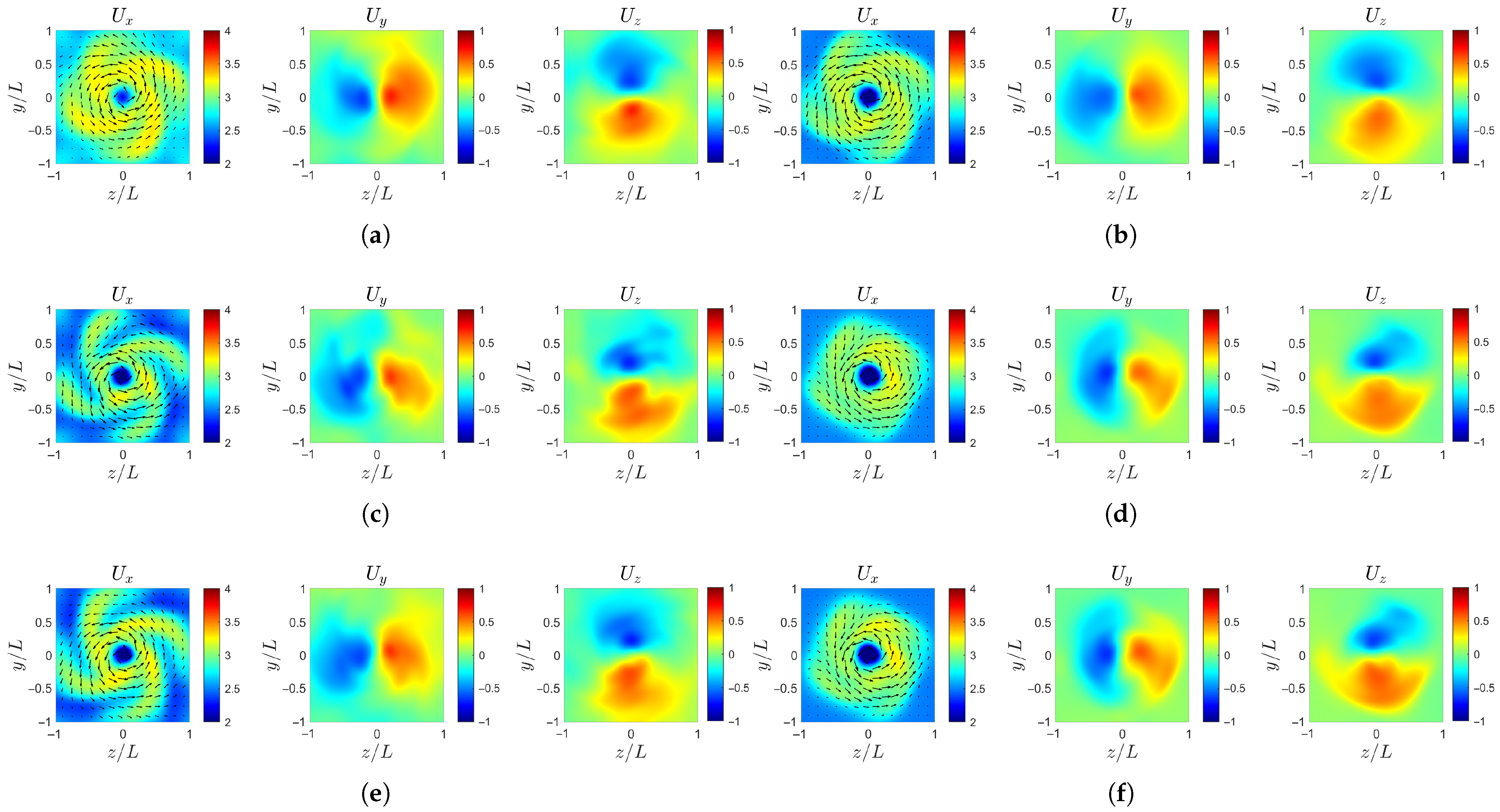

Further downstream, as shown in Figure 15, the spiral structures continue to evolve, gradually stretching and winding into distinct helical arms. The high-speed regions are flung outward along the spiral trajectories, while the low-speed regions expand in between, leading to an alternating pattern of velocity bands. This process is most evident in case-b (Figure 15d), where the large-scale Fourier mode amplitude dominates.

Figure 15.

Instantaneous velocity profile at : (a) case-ori at . (b) case-ori at . (c) case-b at . (d) case-b at . (e) case-c at . (f) case-c at . (g) case-d at . (h) case-d at .

Ultimately, as shown in Figure 16 and Figure 17, the spiral structures tend to smear out, and the velocity distribution approaches concentric rings, indicating the gradual homogenization of the wake velocity. Specifically, in the axial velocity , the outer low-speed region is the first to become uniform, while the inner region shows a sequential decay of the spiral arms. The case-b loses its spiral features most rapidly, followed by case-c and case-d, whereas case-ori maintains the spiral structures for the longest distance downstream. For the transverse velocity components, case-ori and case-d, which have comparable large-scale and small-scale amplitudes, achieve a symmetric balance earlier, whereas case-b and case-c, dominated by either large or small scales, display more persistent asymmetry before reaching equilibrium.

Figure 16.

Instantaneous velocity profile at : (a) case-ori at . (b) case-ori at . (c) case-b at . (d) case-b at . (e) case-c at . (f) case-c at . (g) case-d at . (h) case-d at .

Figure 17.

Instantaneous velocity profile at : (a) case-ori at . (b) case-ori at . (c) case-b at . (d) case-b at . (e) case-c at . (f) case-c at . (g) case-d at . (h) case-d at .

5.6. Vorticity Field

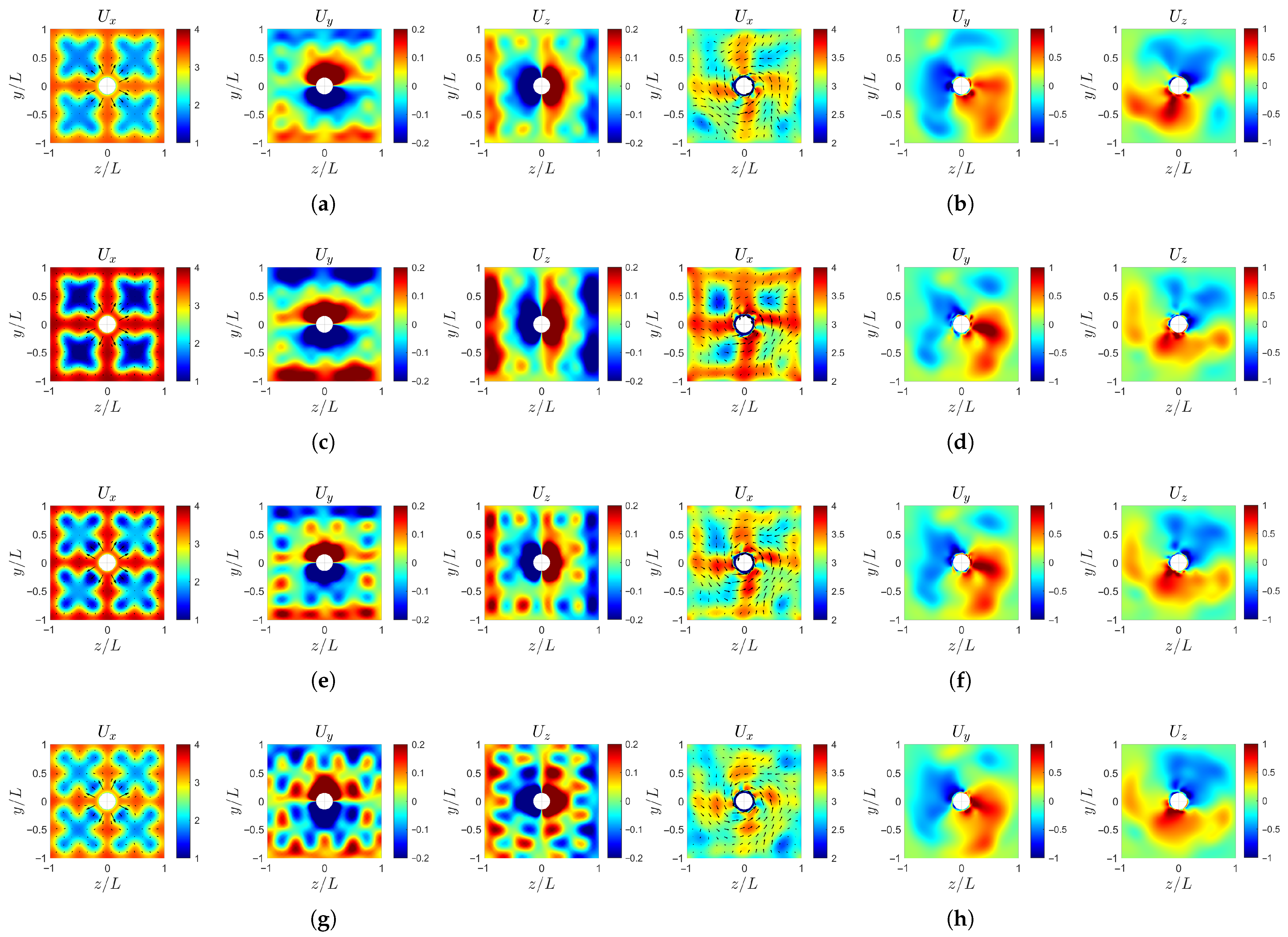

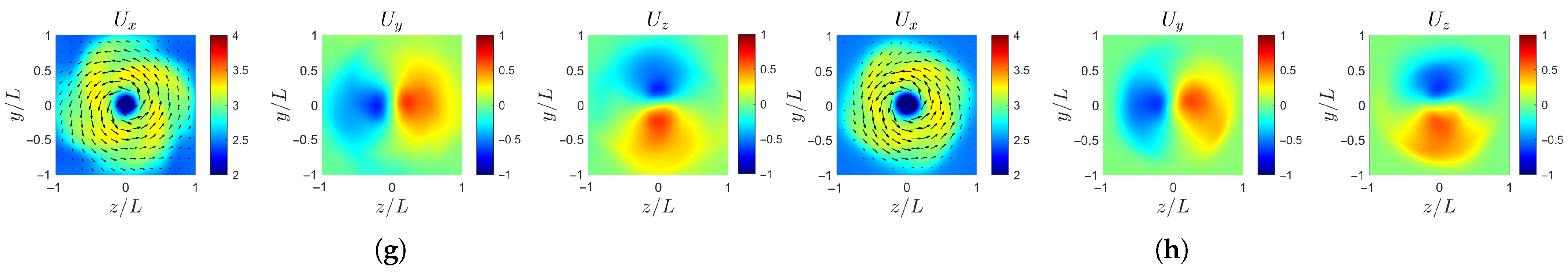

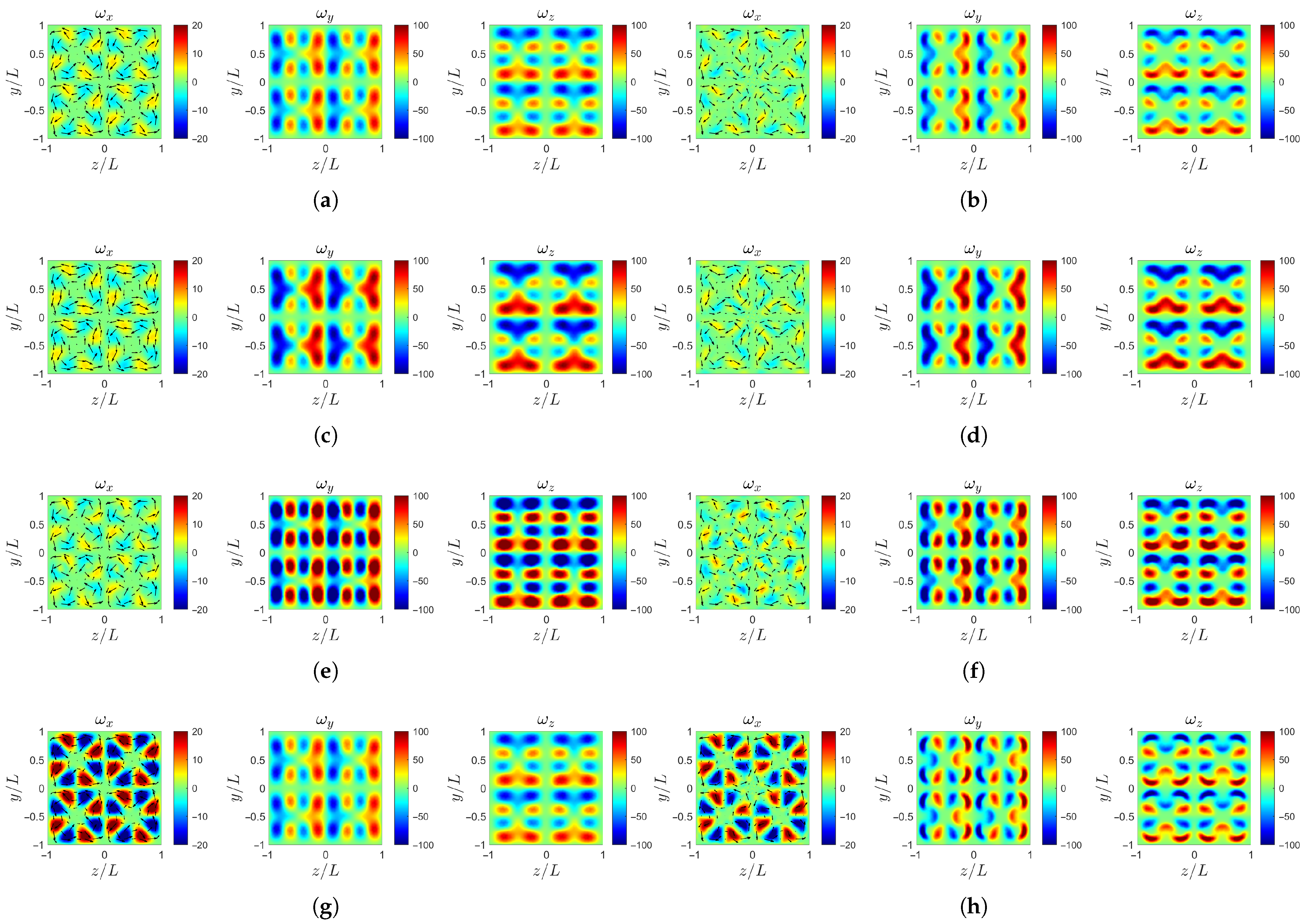

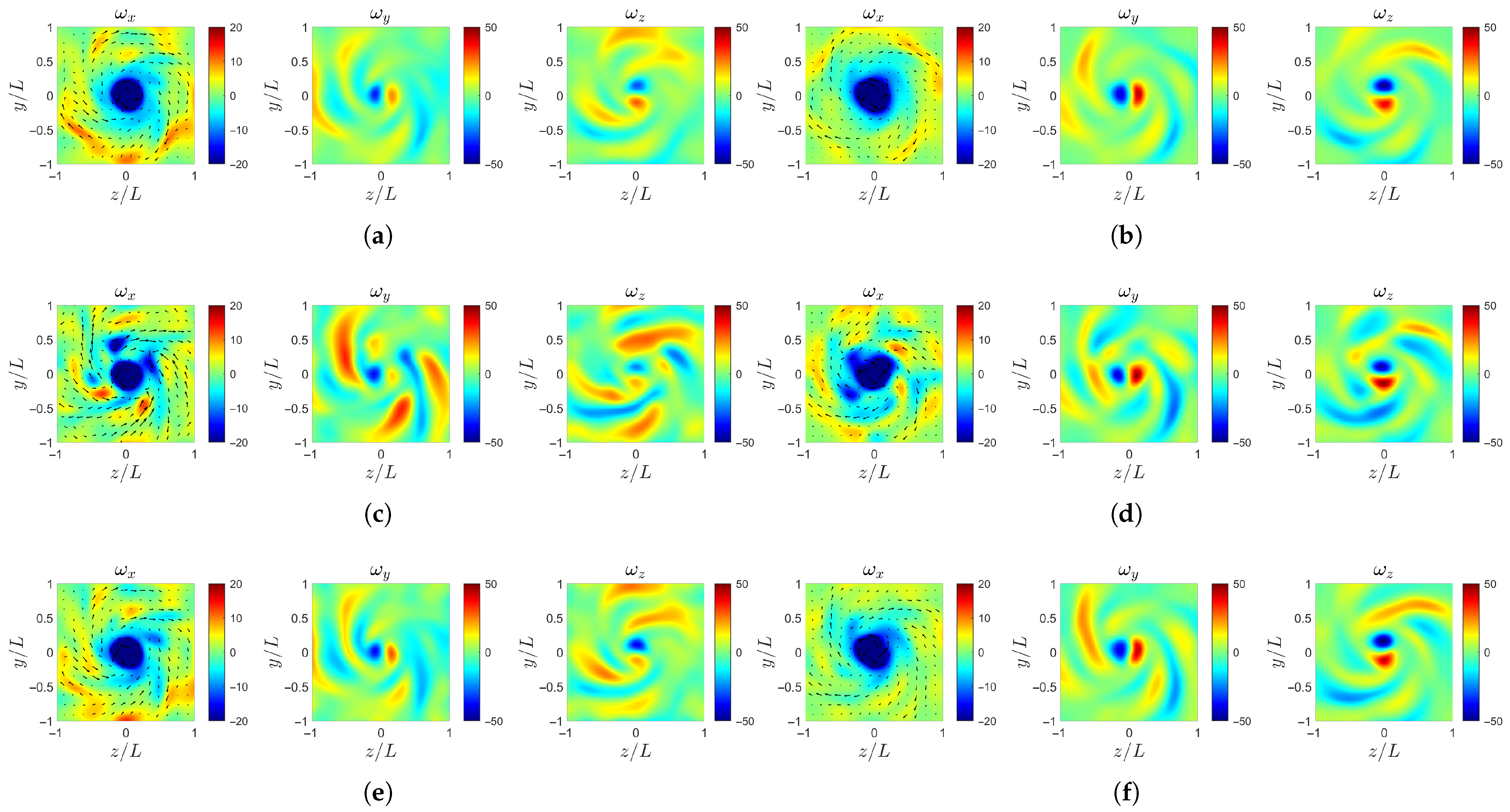

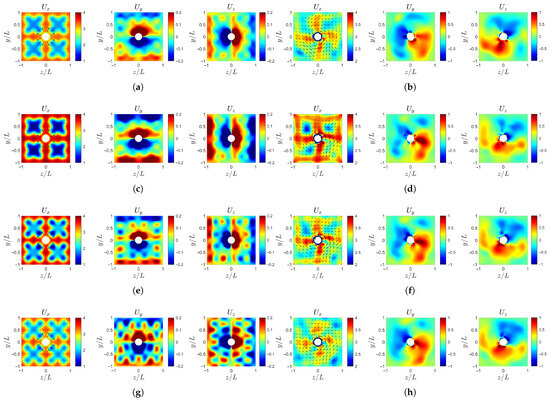

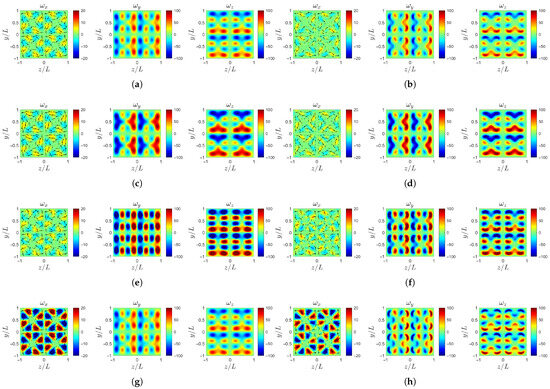

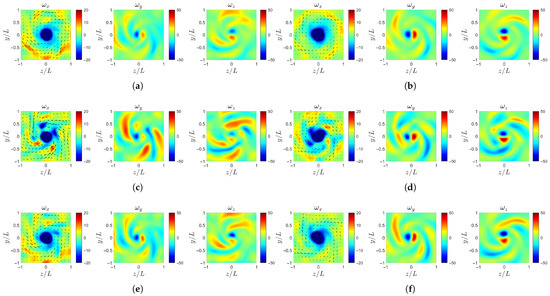

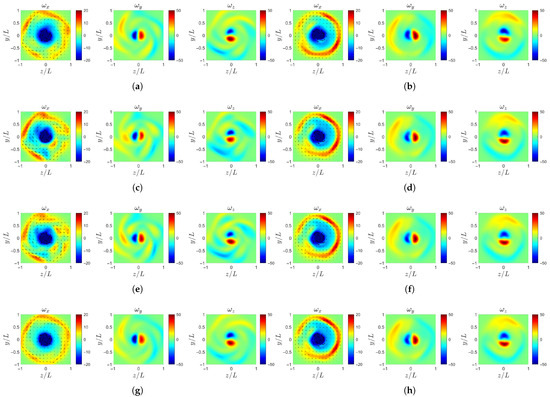

The analysis of the vorticity fields also focuses on the region and , comparing the four cases to reveal the effects of the Fourier mode amplitudes and the transverse perturbation amplitude on the vorticity distributions along streamwise sections. The vorticity profiles are extracted from the instantaneous flow field at . The vorticity profile of is superimposed with the directions of transverse components and , which are indicated by arrows.

Figure 18a,c,e,f show the vorticity fields at the inlet for the four cases. At this location, the initial conditions show that an increase in the transverse perturbation amplitude d primarily enhances the streamwise vorticity . The increase of b and c in axial inflow intensifies and .

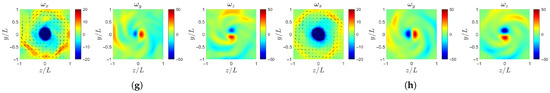

Figure 18.

Instantaneous vorticity profile at : (a) case-ori at . (b) case-ori at . (c) case-b at . (d) case-b at . (e) case-c at . (f) case-c at . (g) case-d at . (h) case-d at .

Further downstream at the interface , the vorticity fields are shown in Figure 18b,d,f,h. Here, case-b with the highest large-scale Fourier mode amplitude exhibits a reduction in the streamwise vorticity . Conversely, case-c with the highest small-scale Fourier mode amplitude shows an increase in the vorticity amplitude within the high regions. For all four cases, the transverse vorticity components and develop clearer structural patterns and enhanced amplitudes compared to the inlet.

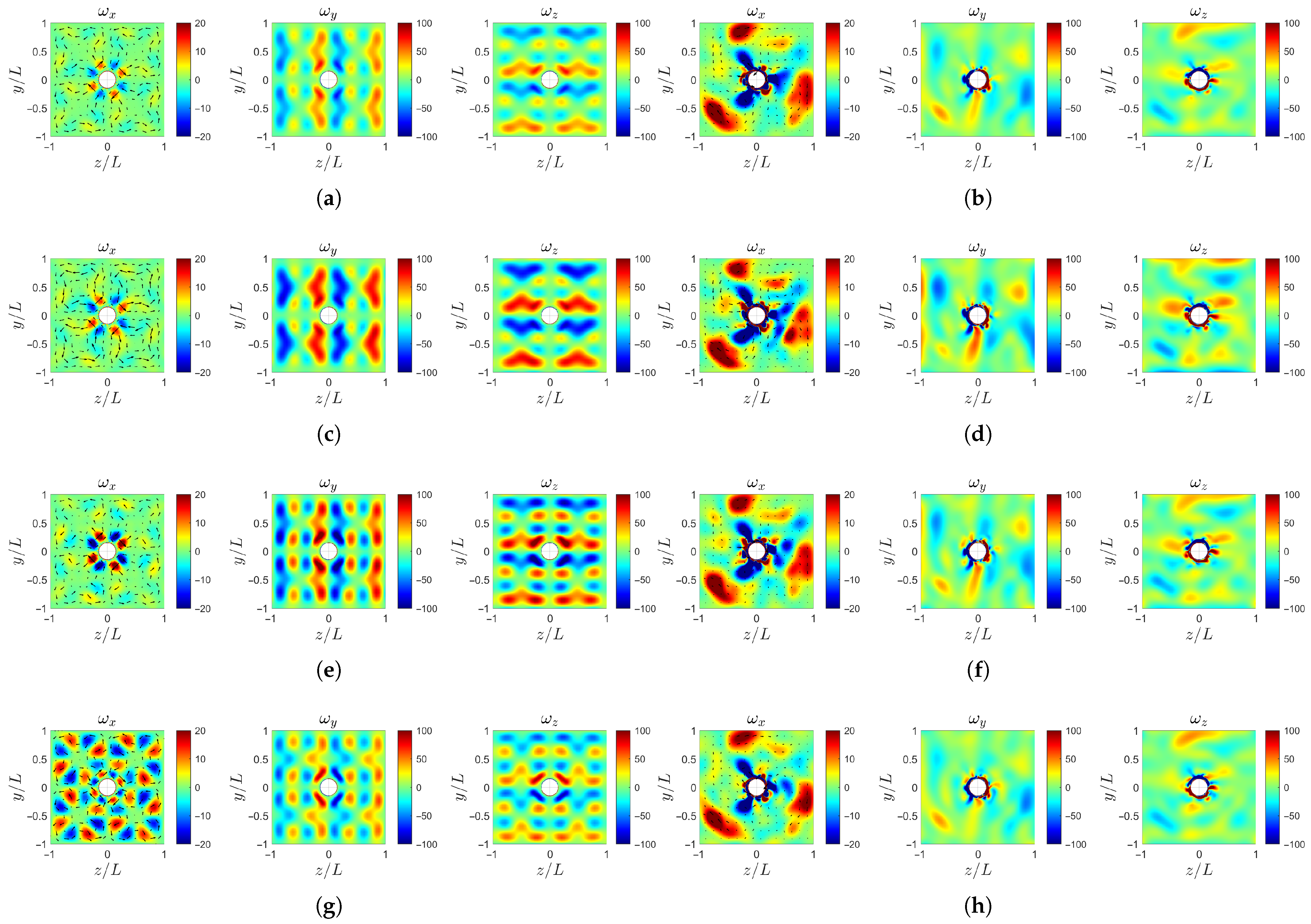

Figure 19 shows the vorticity field near the propeller model. Upstream at the hub , the vorticity near the hub surface increases sharply due to the strong shear layer generated at the solid boundary. After the flow passes through the rotating blades, at the downstream location , distinct regions of high streamwise vorticity are formed in the wake of the three blades. As the large-scale Fourier mode amplitude increases, the transverse vorticity components and downstream of the blades are intensified, as shown in Figure 19d. This enhancement indicates stronger cross-plane shear and secondary vortical motions induced by the large-scale inflow non-uniformity, which promote vortex interactions and contribute to increased wake distortion.

Figure 19.

Instantaneous vorticity profile at : (a) case-ori at . (b) case-ori at . (c) case-b at . (d) case-b at . (e) case-c at . (f) case-c at . (g) case-d at . (h) case-d at .

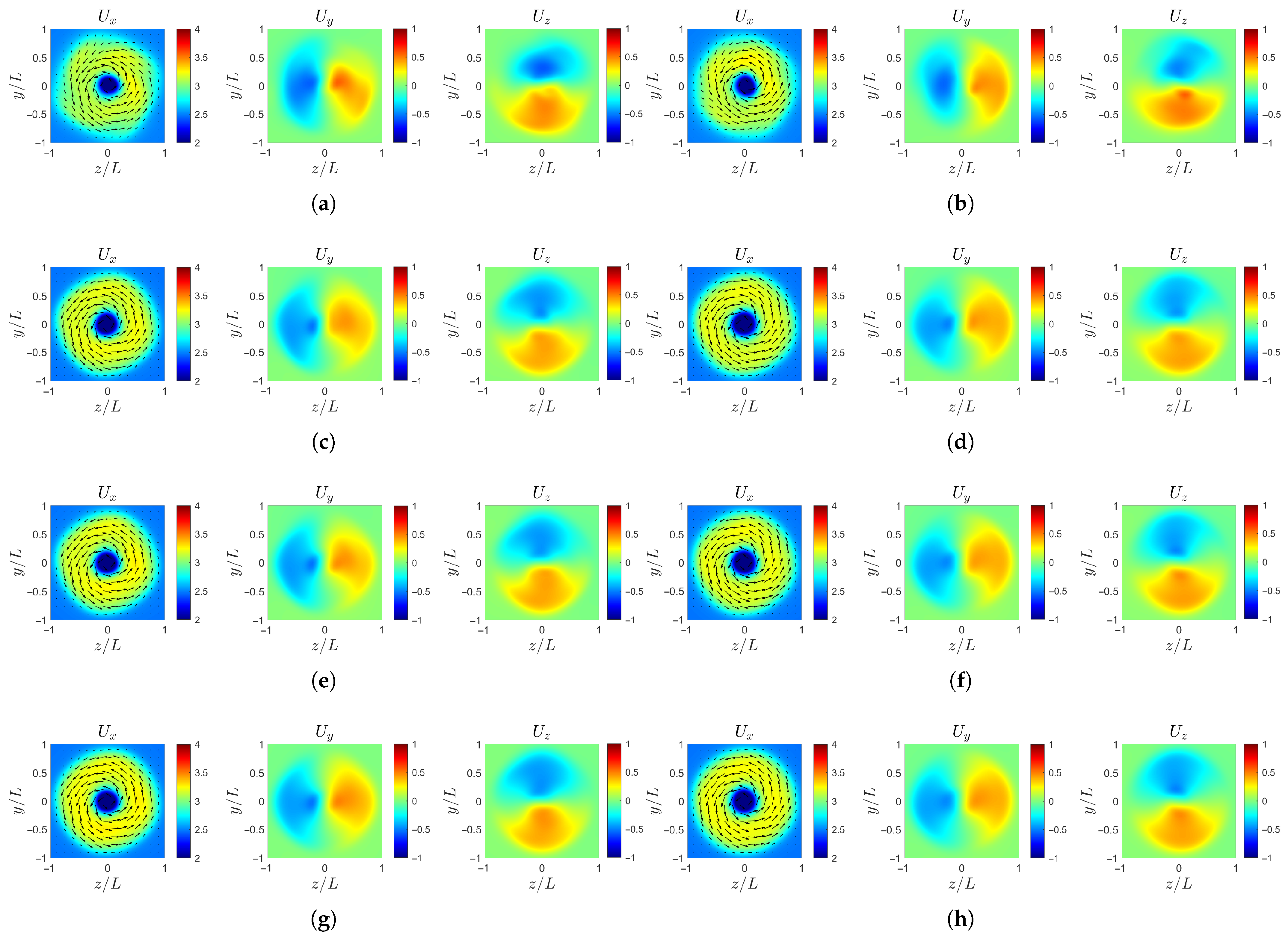

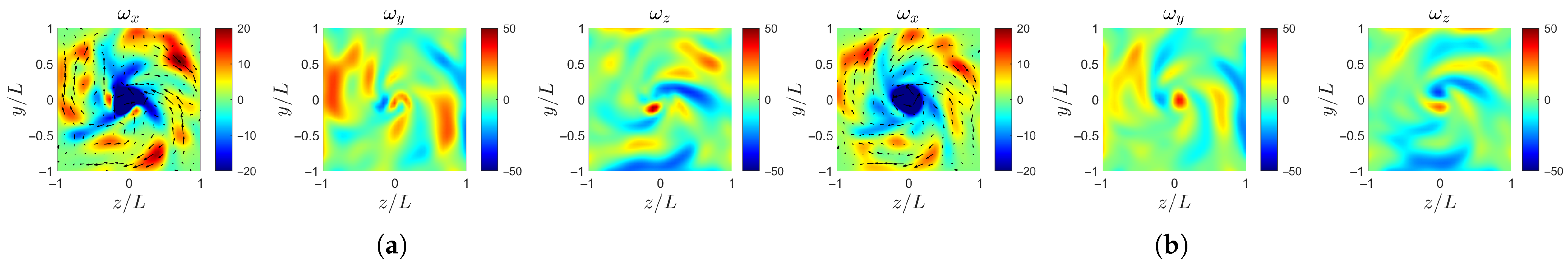

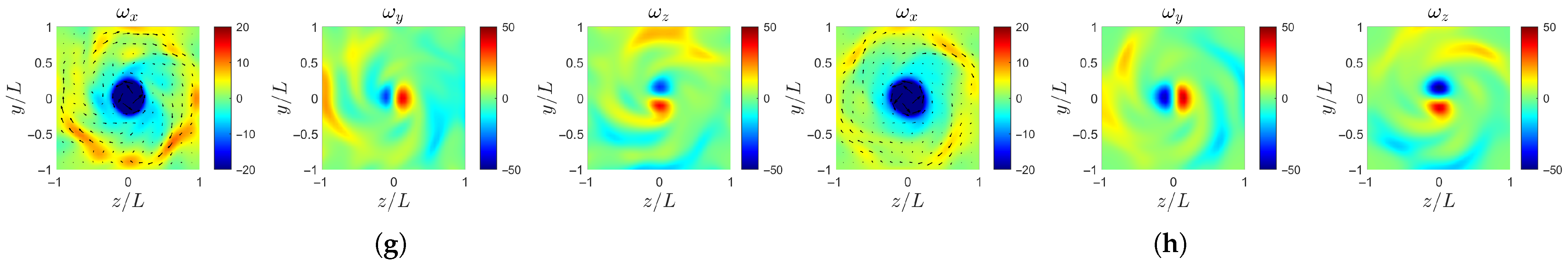

Further downstream, as shown in Figure 20 and Figure 21, the high-vorticity regions of gradually break up into smaller-scale structures. The rate of this evolution differs significantly among the cases. The case-d first develops circular high-vorticity regions (Figure 21g) at . Then, the case-ori with similar circular patterns appears later at (Figure 20b). For the case-b and case-c, the evolution proceeds more slowly, and the circular structures do not emerge until (Figure 22c,e). Regarding the transverse vorticity components and , all four cases exhibit spiral structures at the location . Among them, the case-c and case-ori form more stable and symmetric spiral patterns earlier, whereas case-b and case-d display a delayed development.

Figure 20.

Instantaneous vorticity profile at : (a) case-ori at . (b) case-ori at . (c) case-b at . (d) case-b at . (e) case-c at . (f) case-c at . (g) case-d at . (h) case-d at .

Figure 21.

Instantaneous vorticity profile at : (a) case-ori at . (b) case-ori at . (c) case-b at . (d) case-b at . (e) case-c at . (f) case-c at . (g) case-d at . (h) case-d at .

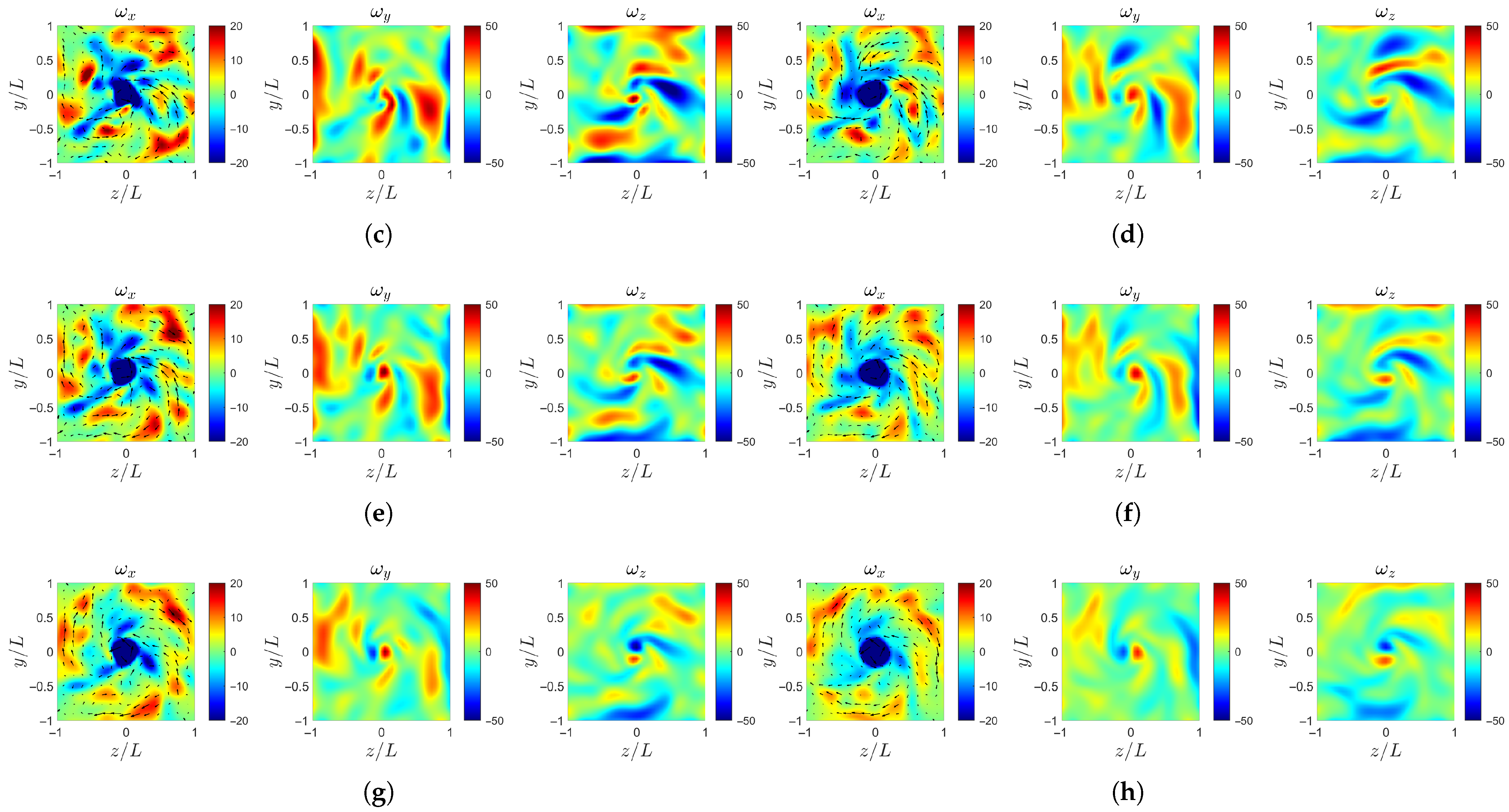

Figure 22.

Instantaneous vorticity profile at : (a) case-ori at . (b) case-ori at . (c) case-b at . (d) case-b at . (e) case-c at . (f) case-c at . (g) case-d at . (h) case-d at .

Ultimately, as shown in Figure 22, the streamwise vorticity in all four cases evolves into similar ring-like structures at the downstream location of . However, the evolutionary path to this state from differs. The case-b and case-c exhibit a more complex breakdown, characterized by the shedding of small-scale, high-vorticity regions. Concurrently, the transverse vorticity and undergo a process of symmetrization.

6. Conclusions

In this study, the dynamic response of a marine propeller under a two-scale inflow was systematically investigated using URANS simulations. A typical non-equilibrium two-scale wake inflow condition is employed, aiming to consider more realistic influences compared with traditional artificial inflow conditions. In the present wake inflow condition, three main parameters, namely b for large-scale Fourier mode amplitude, c for small-scale Fourier mode amplitude, and d for transverse perturbation amplitude, are considered, respectively. The following conclusions are drawn:

- The unsteady thrust () on a single blade is primarily dictated by the harmonic number of the axial inflow (). Although the unsteady lateral forces (, ) are induced by the non-uniform axial inflow, their behavior is mainly governed by the blade passing frequency and transverse perturbation. For the entire propeller, the frequency characteristics are determined by the blade phase superposition, resulting in dominant responses at frequencies that are integer multiples of the single blade force frequency.

- The increase of b, c, and d all lead to a reduction in the time-averaged total thrust of the propeller, indicating that inflow non-uniformity has a negative impact on propulsive performance. In particular, the non-uniformity induces larger-amplitude unsteady loads on single blades. Among them, the large-scale Fourier mode amplitude b enlarges the high pressure fluctuation region along the leading edge and therefore dominates the amplification of unsteady blade forces, while the small-scale component c mainly introduces higher-order harmonic responses with a weaker influence. In contrast, increasing the transverse perturbation amplitude d reduces the extent of the high pressure fluctuation region along the leading edge and correspondingly suppresses the single blade force fluctuations.

- The vortex structure analysis shows that the tip vortices shed from the propeller blades form coherent helical patterns in the near wake. As the large-scale Fourier mode amplitude b increases, these helical structures become more distorted, exhibiting intensified vortex fragmentation and enhanced vortex–vortex interactions. In contrast, increasing the small-scale amplitude c promotes an earlier breakdown of the helical tip-vortex system while maintaining its overall spatial organization. Meanwhile, stronger transverse perturbations d alleviate vortex distortion and contribute to a more symmetric and coherent helical wake structure downstream.

- The velocity field analysis indicates that the rotating blades dissipate small-scale fluctuations while preserving the core features of the large-scale structures, which subsequently develop into spiral arm-like structures in the wake. The increase of the small-scale Fourier mode amplitude exacerbates the entrainment and suction effect of the hub vortex recirculation zone.

- The rotating blades generate regions of high streamwise vorticity , which are then shed into the wake. Although the initial inflow conditions do not alter the ultimate wake topology, they influence the rate of evolution. Specifically, the progression toward wake homogenization is slowest when the axial inflow is dominated by large-scale amplitude. Conversely, the presence of significant small-scale axial or transverse perturbations accelerates this transition.

In conclusion, we use a non-equilibrium two-scale wake inflow condition to investigate the influence on the propeller. The results reveal that large-scale modes amplify unsteady thrust fluctuations and enhance vortex fragmentation, while small-scale modes produce similar but weaker effects, mainly influencing the high-frequency components of unsteady thrust. In contrast, transverse perturbations reduce inflow non-uniformity, effectively suppress single blade thrust fluctuations, and preserve the coherent vortex structures of the wake. This study highlights the importance of scale effects in propeller unsteady hydrodynamics and provides valuable insights for the optimization of marine propellers and energy-saving devices. The parametric analysis is expected to inspire future research on propeller performance under non-uniform flow conditions. However, the present URANS-based approach cannot fully capture small-scale turbulence or cavitation effects. Future work will extend the two-scale inflow framework to high-fidelity simulations and experimental validation for more accurate prediction of propeller’s performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H. and L.F.; methodology, X.S., X.H. and L.F.; software, X.S.; validation, X.S.; formal analysis, X.S., X.H. and L.F.; writing—original draft preparation, X.S.; writing—review and editing, X.S., X.H. and L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers U2341231 and 12372214.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| URANS | Unsteady Reynolds Averaged Navier Stokes equations |

| LDV | LDLaser Doppler Velocimeter |

| DTRC | David Taylor Research Centers |

| AMI | Arbitrary Mesh Interface |

References

- Carlton, J. Marine Propellers and Propulsion; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Vizentin, G.; Vukelic, G.; Murawski, L.; Recho, N.; Orovic, J. Marine propulsion system failures—A review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecoraro, A.; Di Felice, F.; Felli, M.; Salvatore, F.; Viviani, M. Propeller-hull interaction in a single-screw vessel. In Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on Marine Propulsors (smp), Launceston, Australia, 5–8 May 2013; Volume 13, pp. 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Huyer, S.A.; Beal, D. A turbulent inflow model based on velocity modulation. J. Sound Vib. 2007, 308, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.M.; Hultmark, M.; Smits, A.J. The intermediate wake of a body of revolution at high Reynolds numbers. J. Fluid Mech. 2010, 659, 516–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, W. On wake dynamics of a propeller operating under nonuniform behind-hull condition. Ocean Eng. 2023, 279, 114242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Liang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, L.; Wu, D. Dynamic behaviors of blade cavitation in a water jet pump with inlet guide vanes: Effects of inflow non-uniformity and unsteadiness. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 117, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Long, Y.; Deng, L.; Ji, B.; Long, X. Numerical analysis of propeller cavitation and pressure fluctuations around the INSEAN E779A propeller in a non-uniform wake. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 119310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcu, O.; Lungu, A. The Numerical Study of Propeller Efficiency in Non-Uniform Flow. AIP Conf. Proc. 2011, 1389, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göksu, B. Non-uniform inlet flow definition for highly skewed model propeller by geometric partitioning. Ocean Eng. 2024, 302, 117681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yan, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; He, B.; Sun, T. Study on the interaction characteristics of hull–propeller–appendages of autonomous underwater vehicle based on unsteady conditions. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 119087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Croaker, P.; Li, J.; Hua, H. Experimental and numerical studies on the flow-induced vibration of propeller blades under nonuniform inflow. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part M J. Eng. Marit. Environ. 2017, 231, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, H.; Wu, R.; Cao, L.; Wu, D. Data-Driven Identification of Nonlinear Flow-Induced Vibration Sources for a Cavitating Propeller Under Ship Wake. J. Fluids Eng. 2025, 147, 101211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petricelli, F.; Chaitanya, P.; Palleja-Cabre, S.; Meloni, S.; Joseph, P.F.; Karimian, A.; Palani, S.; Camussi, R. An experimental investigation on the effect of in-flow distortions of propeller noise. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 214, 109682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ding, Y.; Wang, C.; Cao, W. Study on the cavitation characteristics and noise mechanisms of a propeller under non-uniform inflow. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 085152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Dong, L.; Wang, D.; He, J.; Shuai, Z.; Li, W.; Ni, S.; Jiang, C. Propeller hydrodynamic excitation influenced by shafting whirling vibration considering different nonuniform inflow conditions: A numerical study. Ocean Eng. 2023, 288, 116021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, H.A. Low frequency noise from wind turbines: Mechanisms of generation and its modelling. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control 2010, 29, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, X.; Zhou, J.; Huang, Z.; Mei, L. Characteristics of fluid-structure coupling deformation of elastic propellers. Shipbuild. China 2020, 61 (Suppl. S2), 207–213. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Luo, W.; Li, M. Numerical investigation of a propeller operating under different inflow conditions. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 105118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, C.; Qing, W.; Zhang, G. Assessment of RANS and DES turbulence models for the underwater vehicle wake flow field and propeller excitation force. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2022, 27, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Chang, X.; Zhang, Y. Numerical simulation of effective wake field and propulsion performance in a ship with moonpool. Ocean Eng. 2025, 323, 120589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hong, Y.; Wang, R. Hydroelastic optimisation of a composite marine propeller in a non-uniform wake. Ocean Eng. 2012, 39, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.E. Vibrations of a Marine Propeller Operating in a Nonuniform Inflow; Technical Report DTIC Document; David W. Taylor Naval Ship Research and Development Center: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Jessup, S.D. An Experimental Investigation of Viscous Aspects of Propeller Blade Flow. Ph.D. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, X.; Sun, Y.; Huang, S.; Dong, X.; Chen, Y. Investigation on the Cyclostationary Force of Propeller Induced by Spatially Non-Uniform Turbulent Inflow. Ocean Eng. 2024, 313, 119486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Cao, L.; Wu, D.; Yu, F.; Huang, B. Generation and distribution of turbulence-induced forces on a propeller. Ocean Eng. 2020, 206, 107255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, L. Modal analysis of propeller wake dynamics under different inflow conditions. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 125109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; Shao, L.; Fang, L.; Dong, M. Existence of positive skewness of velocity gradient in early transition. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2021, 6, 104608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Fang, J.; Fang, L. Non-equilibrium dissipation laws in a minimal two-scale wake model. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 085105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, C.; Comte-Bellot, G. Turbulence; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Menter, F.R.; Kuntz, M.; Langtry, R. Ten years of industrial experience with SST turbulence model. Turb. Heat Mass Transf. 2003, 4, 625–632. [Google Scholar]

- OpenCFD Ltd. OpenFOAM: The Open Source CFD Toolbox, Version v2412. Available online: https://www.openfoam.com (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Wolf Dynamics. Turbulence Modeling—Advanced Training Using OpenFOAM (Version 2021). Available online: https://www.wolfdynamics.com/training/turbulence/OF2021/turbulence_2021_OF8.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Breslin, J.P.; Andersen, P. Hydrodynamics of Ship Propellers, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; pp. 235–237. [Google Scholar]

- Jessup, S.D. Measurement of Multiple Blade Rate Unsteady Propeller Forces; David Taylor Research Center: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Mahesh, K. Large eddy simulation of propeller wake instabilities. J. Fluid Mech. 2017, 814, 361–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukund, R.; Kumar, A.C. Velocity field measurements in the wake of a propeller model. Exp. Fluids 2016, 57, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).