Abstract

The evolution of a coherent structure in a cylindrical wake was studied through observing its energy contribution to the flow field. Analysis using the proper orthogonal decomposition on the PIV data measured at two Reynolds numbers (Re) of 3840 and 9440 was performed. The coherent structure was identified by checking the Fourier power spectrum for each temporal mode coefficient and selecting those whose peak magnitudes were greater than the smallest magnitude of the identified harmonic frequency family as the large-scale organized motions. The energy contribution by the coherent structure is significantly dependent on Re. The evolution of the energy contribution by the coherent structure exhibits a monotonously decaying trend when moving downstream. The coherent structure primarily contains the Kármán vortices in the near wake. The contribution weight of the secondary vortices gradually increases, along with the streamwise distance, except in the very upstream subregions for the case of Re = 9440. The energy contribution by the secondary vortices immediately behind the cylinder (x/d = 0.5–5.5) was 30% for Re = 9440, in comparison with <1% for Re = 3840, but decayed rapidly to the value of <10% in the downstream subranges.

1. Introduction

The flow in the near-wake region behind a bluff body, incorporating the vortex formation and decay region, has been long a subject of interest to engineers and scientists [1,2,3,4]. Bluff-body wakes are complex because they involve the interactions of three layers, namely, a boundary layer, a separating free shear layer, and a wake, particularly in near-wake regions [1]. As a result, turbulent flows behind a bluff body are complex multi-scale and chaotic motions, spanning across a wide range of spatial and temporal scales, which are referred to as coherent turbulent structures involving coherent vortices (in other words, large-scale organized motions) and small-scale fluctuating motions. The organized motions in a coherent structure are classified using the Kármán vortices, which are the principal motions, and the secondary vortices [5,6]. The secondary vortices can be further split into two types: the longitudinal and Kelvin–Helmholtz vortices [7]. The longitudinal vortex originates from parts of the span-wise vortices and usually has a lower frequency than that of the Kármán vortex [8,9]. The Kelvin–Helmholtz vortex features a convective-type instability of the shear layer, which is principally two-dimensional, akin to a free shear layer [1], and is characterized by a higher frequency than that of the Kármán vortex [10].

Despite extensive progress in the study of free wakes, intending to understand a connection between the near-wake vortex shedding mechanism and the evolution of far-field turbulence characteristics, there remains a persistent challenge [11]. Overcoming this challenge is essential not only for continuously advancing fundamental research on turbulent wake but also for informing strategies of vortex control research. Extensive research on bluff-body dynamics, through both experimental and numerical studies, has been currently reviewed in the paper of Marefat et al. [12]. It is agreed that the Kármán vortex significantly contributes to the mean drag and lift fluctuations and cause flow-induced vibrations and noises. Thus, many studies have recently proposed various flow control methods, including active [4,13,14] or passive [15,16] flow control technologies, to suppress the strength of the Kármán vortex shedding.

The kinematic and dynamical properties of the coherent vortices and small-scale fluctuating motions, such as vorticity, variances in fluctuating velocity components, and energy, govern the way coherent structures grow, evolve, and decay. Almost all studies on the evolution phenomena topics for free/confined turbulent wake dynamics [1,2,11,17], and some studies on the vortex control technologies [11,12,15], were implemented in terms of the kinematic and dynamical properties of velocity, vorticity, variances in fluctuating velocity components, and Reynolds stress, rather than on the energy of the coherent turbulent structures. This is because an exact assessment of the energy contributed by coherent structure was practically impossible due to experimental difficulties in the past [18]. However, an estimate that the near wake holds around 25% of the total energy contained in the coherent structure was very briefly disclosed in an early review paper of Fieldler [18].

Among all the data-driven algorithms for data processing that have been used to determine the spatio-temporal features of turbulent coherent structures, proper orthogonal decomposition (POD) [19], dynamic mode orthogonal decomposition (DMD) [20], and spectral proper orthogonal decomposition (SPOD) [21] have been commonly used in the dynamical studies of turbulent coherent structures [22,23,24]. Among these three data-driven algorithms, POD was the first one developed to extract the essential features from the snapshot sequences of flow fields for experimental measurements or numerical simulations. In contrast to the POD algorithm, the DMD algorithm considers both the temporal (spectral) and spatial orthogonalities, resulting in the phase/frequency information and the corresponding coherent structures, which provides a compact and intrusive manner for understanding the dynamic information of fluid flow. The main difference between SPOD and POD is that the modes in SPOD vary in both space and time and are orthogonal under a space-time inner product rather than only space, which is adopted by POD. Consequently, SPOD is optimal for expressing spatio-temporal coherence in the data. However, since this study was conducted with the approach for identifying a coherent structure that was developed based on the POD algorithm [25,26], the POD method is employed in this study.

Advances in the detection capabilities of spatial and temporal resolutions for the time-resolved particle image velocimetry (PIV) lead to a situation where the measured information for the spatially phase-correlated vorticity can be used to study the dynamics of a coherent structure with POD [22,23]. POD decomposes a large data set into spatial eigenmodes and temporal coefficients that correspond to each eigenmode [6,19]. The eigenvalue for each eigenmode represents the physical contribution of the kinetic energy of the basis, that is, the total kinetic energy of the flow. The eigenmodes are then ordered by their eigenvalue magnitudes, > so that the first mode corresponds to the most energetic component of the data set.

A study on the dynamic structure of a near wake behind a circular cylinder using the PIV technique was performed earlier by our research group [17] by following the conventional method based on velocity, vorticity, variances in fluctuating velocity components, and Reynolds stress. This study’s aim is to re-investigate the dynamic structure of this near free wake in terms of the energy of the coherent turbulent structure, which is rarely found in the literature. The study used the approach recently developed by our research team [25,26] to identify the coherent structure and then estimated the energy contribution for each multi-dominant, large-scale, organized component using velocity data that were measured using PIV in a turbulent near wake behind a long circular cylinder. The operating parameters for the POD analysis were based on our recent research outcome [27] to guarantee the accuracy of the POD analysis. The coherent structure evolution in the near wake is shown and discussed by observing the variations in the energy contribution and its constitution as a coherent structure along the streamwise (main flow stream) direction.

2. Experimental and Analysis Methods

2.1. Experimental Facility and Operational Conditions

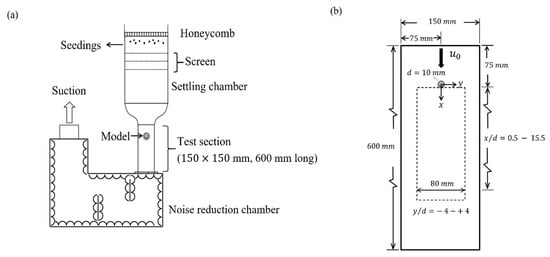

Experiments were conducted in a vertically downward, rectangular wind tunnel that had a test section with a cross-sectional area of 150 mm by 150 mm and a length of 600 mm (Figure 1). A smooth circular cylinder with a diameter of 10 mm (d) and 150 mm length (), which acted as a wake generator, was mounted in the middle of the cross-section, 75 mm down from the top of the test section (Figure 1b). The blockage ratio for the cylinder in the test section was 3.49 × 10−3, so that the blockage effect of the cylinder in the test section could be negligible. Two freestream velocities of 5.97 and 14.67 m/s, which were equivalent to Reynolds numbers (based on the diameter of the circular cylinder) of 3840 and 9440, respectively, were studied and are hereafter named as Cases 1 and 2, respectively. These two cases were in the subcritical wake regime (Re = ), with St ≈ 0.21 [28]. The Strouhal number is defined by

where f and are the Kármán vortex-shedding frequency and the upstream freestream velocity (Figure 1b), respectively. The slenderness ratio for the cylinder () was 15. However, a mild three-dimensional flow in the form of a wavy base behind this nearly two-dimensional geometry of the bluff body was present in the wake [2]. The streamwise (x) and transverse (y) coordinates were positive downward and positive toward the right, respectively. The origin was set at the cylinder’s center. The inlet turbulent intensity, which was measured at x = , was about 1%. The measured domain was 150 mm × 80 mm (x by y) in the central plane of the test section (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of the suction-type wind tunnel and (b) layouts of the test section and PIV measurement domain.

2.2. PIV System and Measurement Conditions

A two-component PIV system was used for the velocity measurement. A continuous-type, green-color laser of 3.7 W power with a cylindrical lens of 75 mm focal length generated a parallel, homogeneous light sheet with a dimension of 50 mm in width and 3 mm in thickness in the performance of PIV measurement. For image acquisition, a high-speed camera system (FASTCAM SA 5, Photron Co., Tokyo, Japan) was paired with a Nikon AIS 85 mm f/1.4 lens (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and a Tokina 12 mm extension tube (Kenko Tokina Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). For use of a continuous laser, the timing of the pulses in PIV measurement was determined by the exposure time, which was dependent on the shutter speed of the camera. The seedings were silicon dioxide, whose density was 2600 kg/m3, with a nominal mean size of 1.9 μm. Considering a trade-off between acquiring enough intensity on the image sensor and reducing the blurred image of seedings [29], the shutter speed was set to be 10−5 s. The system thus operated at a frame rate of frame/s, with a spatial resolution of 1024 pixels by 1024 pixels, which was 20 mm × 20 mm in real dimensions. The cross-sectional function was calculated using an ultimate interrogation window of 32 pixels by 32 pixels, with a 50% overlap. The uncertainty of the PIV measurement was estimated to be about 3.1% (see Table 2 in Chen and Chang [17]). A total of 43,683 PIV image pairs were collected in the experiment. More information on the employed operating conditions for the PIV measurement is referred to Chen and Chang [17].

2.3. POD Analysis

The snapshot POD method [19], which discretizes time rather than space and fits the present study owing to the number of snapshots in time far exceeding the number of spatial points [27], was used to decompose the two-dimensional temporal flow field at instant time in terms of the triple decomposition [30] as follows:

where , and are components of the mean, organized, and randomly fluctuating motions, respectively; and are the spatial eigenmodes and the temporal mode coefficients, respectively. The upper bound of the series, N, is the same as the total collected PIV image pairs in the experiment, that is, 43,683. However, considering the accuracy (3.1%) for the employed PIV measurements in our current study, the minimum numbers of image pairs for confident spatial reconstruction were 14,180 and 19,020 in the wake subregions of 0.5–5.5 d and 5.5–10.5 d, respectively, for Case 1, while 19,400 and 25,580 were required in the wake subregions of 0.5–5.5 d and 5.5–10.5 d, respectively, for Case 2 [27]. This reveals a trend that the minimum number of image pairs for confident spatial reconstruction increases as either Re increases or the testing subregion moves downstream. As a result, the upper bound of the series shown in Equation (2), that is, 43,683, was used for all following POD analyses, which allowed for attaining statistically stationary results for the POD analyses of Cases 1 and 2, even when moving from the subregions of 0.5–10.5 d to a further downstream subregion of 10.5–15.5 d. The background noise frequencies for the wind tunnel were measured at the two investigated freestream velocities before installing the cylinder, i.e., the wake generator. The background noise frequency was removed from the power spectrum of each mode for each case prior to the POD analysis.

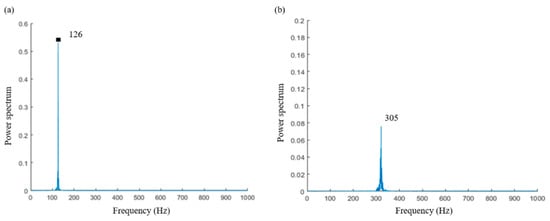

Figure 2 shows two power spectra of the streamwise velocities measured at the locations (x/d = 2, y/d = 0.55) for Case 1 and (2, 0.57) for Case 2, which were at around the wake width, as defined by u/ = 0.95 [17]. The Kármán vortex shedding (or first harmonic) frequencies are 126 and 305 Hz for Cases 1 and 2, respectively (Figure 2), which lead to St values equal to 0.211 and 0.208, respectively, in accordance with Equation (1). The field of view (FOV) must be capable of catching the maximum spacing (λ) between vortices in the Kármán vortex street, which is estimated with λ = d/St. Thus, the λ values needed to be larger than 4.74 d and 4.81 d for Cases 1 and 2, respectively. The FOV was set to be 5 d for the PIV measurements and the following POD analysis. For more information on the employed POD method, the reader is referred to our previous study [27].

Figure 2.

Fourier power spectra of the streamwise velocities for (a) Case 1 at location (x/d = 2, y/d = 0.55) and (b) Case 2 at location (x/d = 2, y/d = 0.57).

3. Identification Procedure for Coherent Structure in Wake

Identification of the coherent structure, that is, large-scale organized motions, for each eigenmode of Equation (2) followed the approach developed by Chu and Chang [25] and is briefly outlined in the following: As reported in our previous studies [25,26,27], for the Fourier spectrum analysis of each mode coefficient for both investigated cases, for example, Figure 3 in Chang et al. [27], there exist at most three (first, second, and third) harmonic frequencies in the integral-scale subrange of the frequency domain, while the higher harmonic frequencies are located beyond the inertia subrange (in other words, the Taylor microscale, which is classified as the randomly fluctuating component in Equation (2)) of the frequency domain. These three large-scale harmonic frequencies (126, 252, and 378 Hz for Case 1 and 305, 610 and 915 Hz for Case 2) are hereafter referred to as the respective harmonic frequency families for Cases 1 and 2. Since the members of the harmonic frequency family are large-scale organized motions in the Kármán vortex street, the peak frequencies whose magnitudes are larger than the smallest magnitude of the harmonic frequency family in the Fourier power spectrum were taken as the large-scale organized motions [23,25] for each eigenmode. The non-harmonic peak frequencies were the secondary vortices that consisted of the longitudinal and Kelvin–Helmholtz vortices.

4. Results and Discussion

A snapshot of the flow visualization in the near wake for Case 1 is presented in Figure 3. It shows a vortex-shedding process that possesses a clearly coherent structure. According to Table 3 shown in Chen and Chang [17], the developments of the half wake widths on the positive lateral (y) side, which is defined by the lateral (y) position u/ = 0.95, was from 0.783 d (at x/d = 1.8) to 1.737 d (at x/d = 10) for Case 1 and from 0.872 d (at x/d = 1.59) to 1.816 d (at x/d = 10) for Case 2. The setting lateral domain between y/d = 4 to 4 (Figure 1b) was wide enough to cover the entire lateral region of the wake in the streamwise domain of 0.5 d to 15.5 d for this study.

Figure 3.

Snapshot of the flow visualization in the near wake for Case 1.

Three streamwise subranges (each with the size of one FOV) were 0.5–5.5 d, 5.5–10.5 d, and 10.5–15.5 d, each of which was analyzed to investigate the evolution of the energy contribution for the coherent structure in the near wake. Each streamwise subrange was associated with the lateral size between −4 d and 4 d (Figure 1b), so that the PIV measurement was definitely capable of covering the complete wake flow domain in the study.

The streamwise subrange of 5.5–10.5 d for Case 2 was taken as an example in the study to demonstrate how to estimate the percentages of kinetic energy that are contributed by the coherent structure and harmonic frequency family. Table 1 presents the percentages of kinetic energy in the entire eigenmodes contributed by the first 25 modes in the streamwise subrange of 5.5–10.5 d for Case 2. Note that the spatial eigenmodes shown in Equation (2) are ordered by the eigenvalue magnitudes. The kinetic energy percentages of the entire eigenmodes for the first and second modes are 19.48 and 14.29, respectively. After these first two modes, the value decreases quickly and drops to 0.5427% of the total kinetic energy at the 25th mode, and the values for the further modes (up to the 43,683rd mode in the study) monotonously collapse to a negligible level. This decreasing trend can be generally observed from all the investigated streamwise subregions of both cases, such as those shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5 in the flow subregion of 0.5–5.5 d for Cases 1 and 2, respectively, in our previous study [27]. Thus, the total number of modes collected to estimate the kinetic energy, contributed by the coherent structure in each investigated streamwise subregion of the two cases, was set when its cumulative kinetic energy reached just over 80% of the entire eigenmodes’ total kinetic energy, of which the ratio of the kinetic energy that is contributed by coherent motion to the kinetic energy for all the eigenmodes is less than 0.01%.

Table 1.

Identification of the large-scale motions and the kinetic energy percentages contributed by the large-scale motions and the harmonic frequency vortices for the first 25 modes in the flow subrange of 5.5–10.5 d for Case 2.

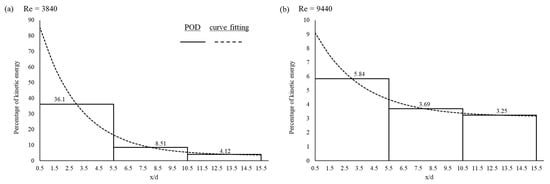

Figure 4.

Snapshots of the (a) span-wise vorticity contour and (b) Fourier power spectrum for the 1st mode coefficient for Case 2 in the flow subregion of 5.5–10.5 d.

Figure 5.

Streamwise evolutions of the percentage of kinetic energy contributed by the coherent structure in terms of the total energy of the entire eigenmodes in (a) Case 1 and (b) Case 2.

Snapshots of the spatial distribution of span-wise vorticity (ω) and the Fourier power spectrum, which was normalized to the total power for the first mode, are, respectively, shown in Figure 4a,b. Here, the span-wise vorticity was calculated using

and nondimensionalized with d/. There is only one dominant peak impulse at 305 Hz, which is the first harmonic frequency in Figure 4b. The integral of the peak impulse curve over the frequency domain gives 0.08666, which is the fraction of the kinetic energy that is contributed by the first harmonic frequency to the frequency domain at the first mode (Table 1). Multiplying this value by 19.48%, which is the percentage of kinetic energy in the entire eigenmodes for the first mode, yields 1.688%, which represents the percentage of kinetic energy contributed by the coherent structure in the entire eigenmodes for the first mode (Table 1). The result obtained from the analysis of the temporal coefficient for the second mode is similar to that for the first mode; that is, there is only one dominant peak impulse at the first harmonic frequency, but the time history of the second mode coefficient features a phase lag of 90° behind that of the first mode coefficient. Such similar results happen in all investigated subregions for both cases (for example, see Figure 2 and Figure 3 in the flow subregion of 0.5–5.5 d for Case 1 in Chu and Chang [25] for details). The integral of the peak impulse curve over the frequency domain gives 0.08192, which is the fraction of the kinetic energy contributed by the first harmonic frequency to the frequency domain at the second mode (Table 1). The percentage of kinetic energy contributed by the coherent structure to the entire eigenmodes for the second mode was calculated by multiplying this value by 14.29%, which is the percentage of kinetic energy in the entire eigenmodes for the second mode (Table 1), yielding 1.17% (Table 1).

There are no dominant frequencies in each power spectrum of the temporal coefficient for the next three (third, fourth, and fifth) modes, but multiple dominant frequencies are observed in the power spectra of the temporal coefficients from the sixth to the seventeenth modes. For example, the first and second harmonic frequencies and some non-harmonic frequencies, which are classified as secondary vortices, are observed in the sixth mode (Table 1), and the most dominant vortex is a non-harmonic one (i.e., the secondary vortex). Similar situations also occur in the seventh to the seventeenth modes. Nevertheless, the most dominant vortices in the 21st and 23rd modes are the first harmonic frequency. The integral of all peak impulses, which are identified as large-scale organized motions, over the frequency domain for the sixth mode gives 0.03718. Multiplying this value by 3.378%, which is the percentage of kinetic energy in the entire eigenmodes for the sixth mode, yields 0.1256%, which denotes the percentage of kinetic energy in the entire eigenmodes that is contributed by the coherent structure in this mode (Table 1). Using a similar calculation procedure, an integral of the peak impulses limited to members of the harmonic frequency family over the frequency domain for the sixth mode gives 0.005506%, which denotes the percentage of kinetic energy in the entire eigenmodes that is contributed by the harmonic frequency family (Table 1). After performing all analysis procedures for the first 25 modes and recording the results in Table 1, the sums for the kinetic energy that are contributed by the coherent structure and harmonic frequency family are 3.686% and 3.338%, respectively. This shows that the harmonic frequency family contributes 3.338%/3.686% = 90.5% of the kinetic energy of the coherent structure and the remainder is contributed by the secondary vortices. Following the same analysis approach, the sums of the kinetic energy contributed by the coherent structure and harmonic frequency family are calculated for the other subregions (0.5–5.5 d and 10.5–15.5 d) of Case 2 and all three subregions of Case 1. All the calculated results are plotted in Figure 5, which show the streamwise evolutions of the energy contribution for the coherent structure in both cases. The detailed information and data of these analyses other than the demonstrated one is given in Lin [31]. The decaying trends for Case 1 (Figure 5a) and Case 2 (Figure 5b) are, respectively, fitted using a three-parameter exponential function as follows:

These two fitting curves are also plotted in their corresponding figures. It is interesting to observe from the fitting curve for Case 1 (Figure 5a) that the percentage of kinetic energy for the wake in the vicinity around the cylinder (x/d ) for Case 1 at Re = 3840 is almost all contributed by the coherent structure (>85%) as extrapolated with Equation (4). This phenomenon warrants further study to explore the connection between the flow separation process and the initiation of the vortex shedding mechanism in the future.

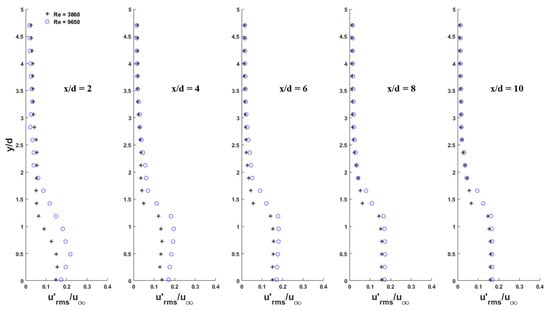

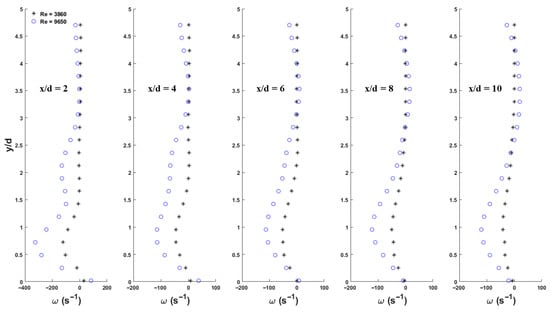

An estimate of an ~25% energy contribution by a coherent structure in the near wake was reported in an early review paper [18], without giving information regarding Re, location in the flow, and the estimation approach; this value falls within the range covered in Figure 5a. Figure 5 shows that the energy contribution ratio of the coherent structure is significantly dependent on Re and its streamwise subregion in the near wake. According to Dynnikova et al. [32], the Kármán vortex street decays until the transformation into a secondary vortex street with a low frequency and stronger vortices in the far wake. The streamwise evolutions of the contribution percentages of the kinetic energy by coherent structure for the two cases in Figure 5 do meet this trend. There are large reductions in the contribution percentages of the kinetic energy in the coherent structure, particularly in the very upstream subregions, as the Re number increases from 3840 (Case 1, Figure 5a) to 9440 (Case 2, Figure 5b). This is attributed to the fact that the turbulence level, which is contributed by the fluctuating motions in Equation (2), is enhanced with increasing Re value, thereby reducing the weight of the energy that is contributed by the coherent structure in the total energy of the entire eigenmodes in the near wake, that is, the component in Equation (2), as shown in Case 2. Figure 6 and Figure 7 compare the sectional distributions of the root-mean-square fluctuating streamwise and transverse velocity components, respectively, as measured using PIV at the five streamwise stations (x/d = 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10) under two Reynolds numbers of 3860 and 9650, which were compiled from the previous study of our research group [17]. The Re numbers in Figure 6 and Figure 7 are only slightly different from those of the present study, 3860 versus 3840 (Case 1) and 9650 versus 9440 (Case 2); thus, they insignificantly affect the comparison tendencies shown in these two figures. They evidence the trend for enhancing the turbulence intensities along with increased Re value, which can be interpreted with the decay of the kinetic energy contributed by the coherent structure with increasing Re value (Figure 5). Yiu et al. [33] studied the Reynolds number (varying from to ) effects on three-dimensional vorticity in turbulent near wakes. They found a large jump in turbulent dynamics, such as streamwise vorticity and vortex formation length, from Re = 5 to Re = . The results shown in Figure 5 are consistent with the trend observed by Yiu et al. [33].

Figure 6.

Comparison of the sectional distributions of the root-mean-square fluctuating streamwise velocity component at the five streamwise stations of x/d = 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10, as measured under two Reynolds numbers (compiled from [17]).

Figure 7.

Comparison of the sectional distributions of the root-mean-square fluctuating transverse velocity component at the five streamwise stations of x/d = 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10, as measured under two Reynolds numbers (compiled from [17]).

It is known that longitudinal vortices are superimposed on the Kármán vortices above certain Reynolds numbers (>140) [7], causing three-dimensionalities in coherent structures in a circular-cylinder’s wake. The experimental study of Huang et al. [34] revealed that the longitudinal vortices appeared in the span-wise (x, z) plane in the immediate proximity behind the cylinder, and the vortex formation length shrank with increasing Re for the Re range of 2 × to . It also showed that the longitudinal vortices decay rapidly from x/d = 5 to 10 and slowly for x/d > 10. Figure 8 presents a snapshot of the spatial distribution of the span-wise vorticity and Fourier power spectrum for the 12th mode coefficient for Case 1 in the flow subregion of 0.5–5.5 d (see Figure 3 for a snapshot of its corresponding flow visualization). Only two harmonics for the Kármán vortex shedding process at frequencies of 126 Hz (first harmonic) and 252 Hz (second harmonic and the most dominant vortex) are observed in Figure 8. For the non-harmonic frequencies whose amplitudes are larger than the first harmonic frequency, most of them are associated with the lower frequencies than the first harmonic (i.e., Kármán vortex shedding) frequency, and the remaining ones are associated with the frequencies in between the first and second harmonic frequencies. They are, therefore, identified as the longitudinal vortices. The information shows that the longitudinal vortices are the primary constituent of the secondary vortex in a very upstream subregion of a near wake. Table 2 shows the evolutions of the cumulative energy percentage that is contributed by the harmonic frequency family (i.e., the Kármán vortices) to that contributed by the coherent structure for the two investigated cases. For Case 1 at Re = 3840, almost all the coherent structures are initially contributed by the Kármán vortices (99.2%) in the immediate proximity behind the cylinder (x/d = 0.5–5.5); the energy contribution of the longitudinal vortices to the coherent structure is gradually enhanced with increasing streamwise distance. However, for Case 2 at Re = 9440, the energy contribution by the secondary (mainly longitudinal) vortices to that of the coherent structure in the immediate proximity behind the cylinder dramatically jumps to ~30% but decays rapidly to a minor weighting (<10%) in the subregion of x/d = 5.5–10.5, which is consistent with the observation in Huang et al. [34]. The energy contribution by the secondary vortices then returns to the gradual increasing tendency observed in Case 1 in the downstream subregion of x/d = 10.5–15.5. Figure 9 compares the sectional distributions of the mean vorticity, which were measured using PIV, at the five streamwise stations (x/d = 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10) under two Reynolds numbers of 3860 and 9650 [17]. It shows that the profile shapes in the five investigated sections look similar for the case with a low Re of 3860. This can be attributed to a fact observed from Table 2, where the Kármán vortices dominate the coherent structure in the upstream wake subregion (x/d = 2–10) at low Re values. In contrast, the profile shapes for the high Re of 9650 in the first two sections (x/d = 2 and 4) are remarkably different from those for the remaining three downstream sections (x/d = 6, 8 and 10), while the profile shapes for the mean vorticity in the remaining sections (x/d = 6–10) look like the case with a low Re of 3860. This can be interpreted using the results shown in Table 2, as the secondary vortices contribute a noticeable portion (30%) in the coherent structure in the very upstream subregion of x/d = 0.5–5.5 at high Re values. After x/d = 6, it returns to the situation where the Kármán vortices dominate the coherent structure, which is akin to the case with a low Re of 3860. These observations hint that the Reynolds number has a larger impact on the energy contribution reduction for the Kármán vortices than on that of the longitudinal vortices for the Re range of 3840–9440 in the immediate proximity behind the cylinder.

Figure 8.

Snapshots of the (a) span-wise vorticity contour and (b) Fourier power spectrum for the 12th mode coefficient for Case 1 in the flow subregion of 0.5–5.5 d.

Table 2.

Streamwise evolution of the cumulative percentage of kinetic energy contributed by the harmonic frequency family to that by the coherent structure for the two investigated cases.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the sectional distributions of mean vorticity at the five streamwise stations of x/d = 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10, as measured under two Reynolds numbers (compiled from [17]).

Since the present identification of the large-scale organized motions was performed based on the harmonic frequency family, this suggests that the contribution of the secondary vortices could be underestimated (Figure 8), of which there are several peaks whose amplitudes are just smaller than that of the first harmonic frequency but are not considered in the integral calculation. A check was made for the kinetic energy contribution using the first 12 modes in the entire eigenmodes in the streamwise subregion of x/d = 0.5–5.5 for Case 2 (Table 3). The contribution of the kinetic energy by the first 12 modes is 60.26%, in which the coherent structure and the harmonic frequency parts contribute 3.3908% and 3.2855% in the entire eigenmodes, respectively. Note that this requires summing up the first 49 modes to reach 80.01% contribution for the cumulative kinetic energy in the entire eigenmodes [31], in which 5.84% is contributed by the coherent structure (Figure 5). Besides the first four modes, each of which has only one dominant peak at the first harmonic frequency in its frequency domain, multiple dominant frequencies are observed in the fifth, sixth, and 9th–12th modes in Table 3, but they are almost all composed mainly of the nonharmonic frequencies (that is, secondary vortices). Only one member of the harmonic frequency family, that is, the first harmonic frequency, appears in the coherent structures (if they exist) in the 5th–12th modes. This phenomenon is different from that observed in the result shown in Figure 8, which is the Fourier power spectrum for the 12th mode for Case 1 in the same streamwise subregion. This evidences a result shown in Table 2, where the secondary vortices contribute more kinetic energy to the coherent structure in this case (Case 2) than in Case 1 in the streamwise subregion of x/d = 0.5–5.5. According to the results shown in Table 3, the first four modes possess only one peak impulse at the first harmonic frequency, and their sum for the kinetic energy contribution in the entire eigenmodes is equal to 3.2481%, which occupies 3.2481%/80.01% = 4.06% of the total energy in the entire eigenmodes and contributes a fraction as high as 4.06%/5.84% = 0.695 to the kinetic energy of the coherent structure. Thus, such speculation for the underestimation of the energy contribution by the secondary vortices, which are principally from the longitudinal vortices, would not become a noticeable issue for the present study. However, the estimation of the energy contribution for the coherent structure can be further improved by an additional identification process, which will be applied directly to the longitudinal vortices and remains to be developed in the future.

Table 3.

Identification of the large-scale motions and the kinetic-energy percentages contributed by the large-scale motions and the harmonic frequency vortices for the first 12 modes in the flow subrange of 0.5–5.5 d in Case 2.

5. Conclusions

Estimations of the kinetic energy contribution by a coherent structure to the total kinetic energy in the wakes behind a circular cylinder at two Reynolds numbers, which are in the subcritical wake regime, were performed using POD analysis of PIV data for three consecutive streamwise one-FOV subregions, covering an x/d range from 0.5 to 15.5. The coherent structure in the wake was identified by examining the Fourier power spectrum of each temporal mode coefficient. The large-scale organized motions were determined with a criterion, where those impulses with their peak magnitudes are greater than the smallest magnitude of the identified harmonic frequency family (if they exist). The energy contributed by the coherent structure was then calculated from the integral of all these peak impulses over the frequency domain. It was found that the energy percentage contributed by the coherent structure is significantly dependent on Re and its streamwise location in the near wake. The streamwise evolutions of the energy percentage contributed by the coherent structure exhibit a monotonously decaying trend when moving downstream for both the investigated cases. The constitution of the coherent structure was examined. For Re = 3840 (Case 1), almost all the coherent structures are initially contributed by the Kármán vortices in the immediate proximity behind the cylinder, but the energy contribution by the secondary vortices is gradually increased with increasing streamwise distance. In contrast to Case 1, the energy percentage contributed by the secondary vortices, which are mainly from the longitudinal vortices, to that by the coherent structure at Re = 9440 (Case 2) jumps from <1% (Case 1) to 30% in the immediate proximity behind the cylinder (x/d = 0.5–5.5) but decays rapidly to the next streamwise subrange (x/d = 5.5–10.5), which agrees with the observation of the experimental study in the literature [34]. The energy contribution weight by the secondary vortices for Case 2 then gradually increases, following the same tendency observed in Case 1 for x/d > 10.5.

Quantifying the energy evolution of the coherent structure in a turbulent wake can not only enable us to improve our understanding of how the coherent vortex and its constitution evolve in the flow, but also facilitate justifying where the Reynolds decomposition (shown below) can be reasonably applied to turbulence statistics and modeling formulation, instead of the triple decomposition in Equation (2).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.-C.C.; methodology, T.-H.L. and K.-C.C.; validation, T.-H.L.; formal analysis, T.-H.L.; investigation, T.-H.L. and K.-C.C.; data curation, T.-H.L.; original draft preparation, T.-H.L.; writing—review and editing, K.-C.C.; supervision, K.-C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Williamson, C.H.K. Vortex dynamics in the cylinder wake. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1996, 28, 477–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearman, P.W. Near wake flows behind two-and three-dimensional bluff bodies. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aero. 1997, 69–71, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleghani, A.S.; Torabi, F. Editorial: Recent developments in aerodynamics. Front. Mech. Eng. 2025, 10, 1537383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolahipour, S. Review on flow separation control: Effects of excitation frequency and momentum coefficient. Front. Mech. Eng. 2024, 10, 1380675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Smith, C.R. Secondary vortices in the wake of circular cylinder. J. Fluid Mech. 1986, 169, 513–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkooz, G.; Holmes, S.; Lumley, J.L. The proper orthogonal decomposition in the analysis of turbulent flows. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1993, 25, 539–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, R.; Cid, E.; Cazin, S.; Sevrain, A.; Braza, M.; Moradei, F.; Hazzan, G. Phase-averaged measurements of the turbulence properties in a near wake of a circular cylinder at high Reynolds number by 2C-PIV and 3C-PIV. Exp. Fluid 2007, 42, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Sheridan, J.; Welsh, M.C.; Hourigan, K. Three-dimensional vortex structures in a cylinder wake. J. Fluid Mech. 1996, 312, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J.; Zhou, Y.; Antonia, R.A. Longitudinal and span-wise vertical structure in a turbulent near wake. Phys. Fluids 2000, 12, 2954–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chyu, C.; Lin, J.C.; Sheridan, J.; Rockwell, D. Kármán vortex formation from a cylinder: Role of phase-locked Kelvin-Helmholtz vortices. Phys. Fluids 1995, 7, 2288–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, I.D.; Romeos, A.; Giannadakis, A.; MIhalakakou, G.; Panidis, T. Vortex dynamics effects on the development of a confined turbulent wake. Fluids 2025, 10, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marefat, H.A.; Alam, J.M.; Pope, K. Toward scale-adaptive subgrid-scale model in LES for turbulent flow past a sphere. Fluids 2024, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolahipour, S. Effects of low and high frequency actuation on aerodynamic performance of a supercritical airfoil. Front. Mech. Eng. 2023, 9, 1290074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleghani, A.S.; Hesabi, A.; Esfahanian, V. Numerical study of flow control to increase vertical tail effectiveness of an aircraft by tangential blowing. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2025, 26, 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Yun, J.; Lee, J. Control of turbulent flow over a circular cylinder using tabs. Mathematics 2023, 11, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleghani, A.S.; Izadi, M. Multiobjective optimization of a single slotted flap using artificial neural network and metaheuristic algorithms. J. Eng. Mech. 2025, 151, 05025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.C.; Chang, K.C. Experimental study of two-phase turbulent wake using PIV technique. Multiph. Sci. Technol. 2024, 36, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieldler, H.E. Coherent structure in turbulent flow. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 1988, 25, 231–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirovich, L. Turbulence and the dynamics of coherent structure. Q. Appl. Math. 1987, 45, 561–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmid, P. Dynamic mode decomposition of numerical and experimental data. J. Fluid Mech. 2010, 656, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, O.T.; Colenius, T. Guide to spectral proper orthogonal decomposition. AIAA J. 2020, 58, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranyi, P.; Janiga, G.; Zahringer, K.; Thevenin, D. Analysis of different POD methods for PIV measurements in complex unsteady flows. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2013, 43, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S. The identification of coherent structures using proper orthogonal decomposition and dynamic mode decomposition. J. Fluids Struct. 2014, 49, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.D.; Yeh, C.A. Model analysis for three-dimensional instability coupling mechanisms in turbulent wake flows over an airfoil. In Proceedings of the AIAA Science and Technology Forum and Exposition (AIAA SciTech Forum), National Harbor, MD, USA, 23–27 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C.C.; Chang, K.C. Estimating the energy contribution of coherent structure in a cylindrical near-wake flow using proper orthogonal decomposition. J. Fluid Sci. Technol. 2023, 18, JFST0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.H.; Chang, K.C. Analysis on evolution of the energy contribution for coherent structure in cylinder near-wake flow using proper orthogonal decomposition. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Jets, Wakes and Separated Flows (ICJWSF-2024), Florence, Italy, 23–25 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.C.; Lin, T.H.; Chu, C.C. A study for enhancing accuracy of POD analysis for near wake behind circular cylinder. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2025, 168, 111506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshko, A. Experiments on the flow past a circular cylinder at very high Reynolds number. J. Fluid Mech. 1961, 10, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boillot, A.; Prasad, A. Optimizing procedure for pulse separation in cross-correlation PIV. Exp. Fluids 1996, 21, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.K.M.F.; Reynolds, W.W. The mechanics of an organized wave in turbulent shear flow. J. Fluid Mech. 1970, 41, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.H. Parametric Study on POD Analysis of Near-Wake Flow Behind Circular Cylinder. Master’s Thesis, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, July 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Dynnikova, G.Y.; Dynnikov, Y.A.; Guvernyuk, S.V. Mechanism underlying Kármán vortex street breakdown preceding secondary vortex street formation. Phys. Fluids 2016, 28, 054101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, M.W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, T.; Cheng, L. Reynolds number effects on three-dimensional vorticity in a turbulent wake. AIAA J. 2004, 42, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huang, J.F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, T. Three-dimensional wake structure measurement using a modified PIV technique. Exp. Fluids 2006, 40, 884–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).